Slavery in the Ancient Near East on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery in the ancient world, from the earliest known recorded evidence in

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

to the pre-medieval Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

cultures, comprised a mixture of debt-slavery, slavery as a punishment for crime, and the enslavement of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

.

Masters could free slaves, and in many cases such freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

went on to rise to positions of power. This would include those children born into slavery but who were actually the children of the master of the house. The slave master would ensure that his children were not condemned to a life of slavery.

The institution of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

condemned a majority of slaves to agricultural and industrial labor and they lived hard lives. In many of these cultures slaves formed a very large part of the economy, and in particular the Roman Empire and some of the Greek poleis built a large part of their wealth on slaves acquired through conquest.

Ancient Near East

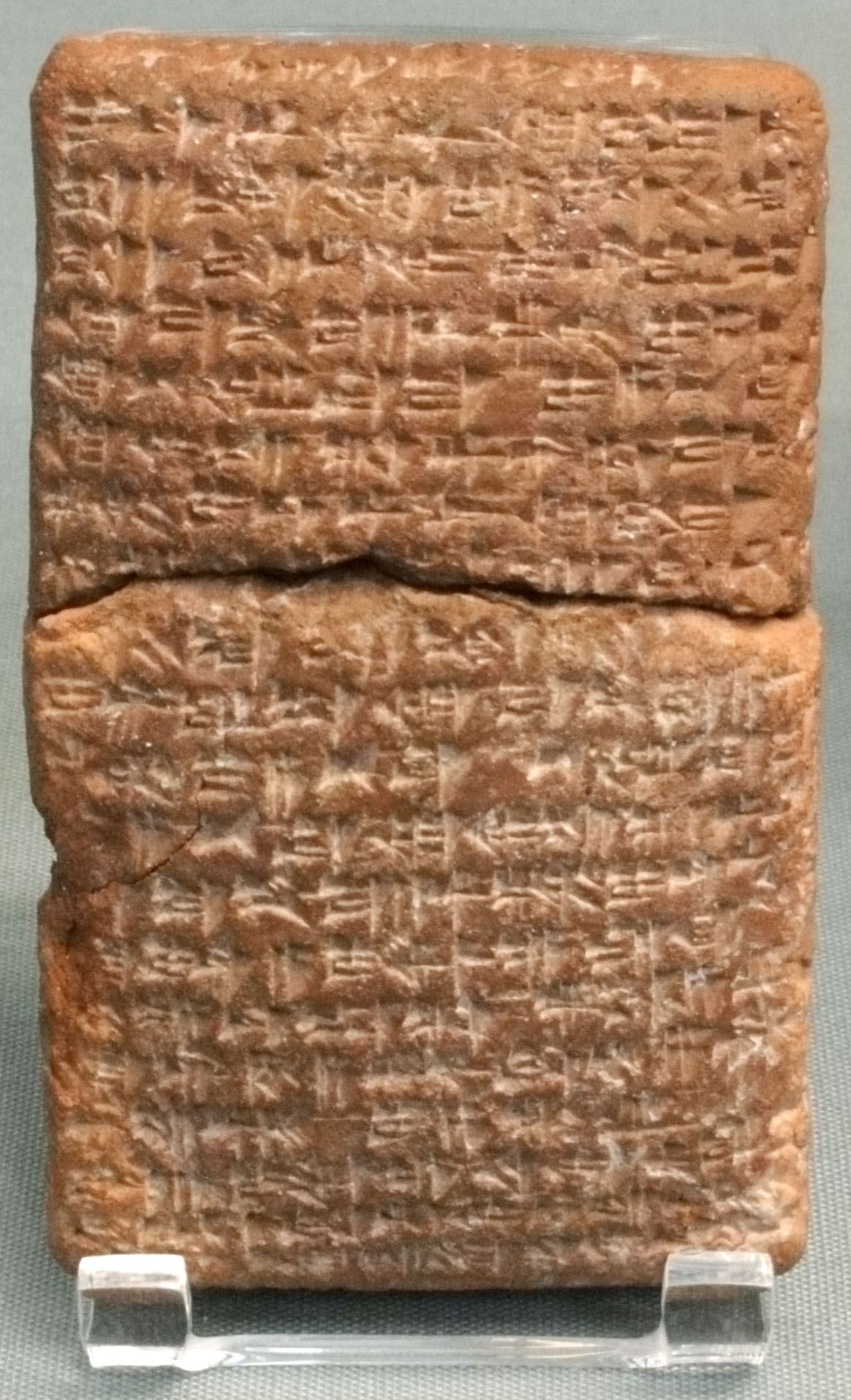

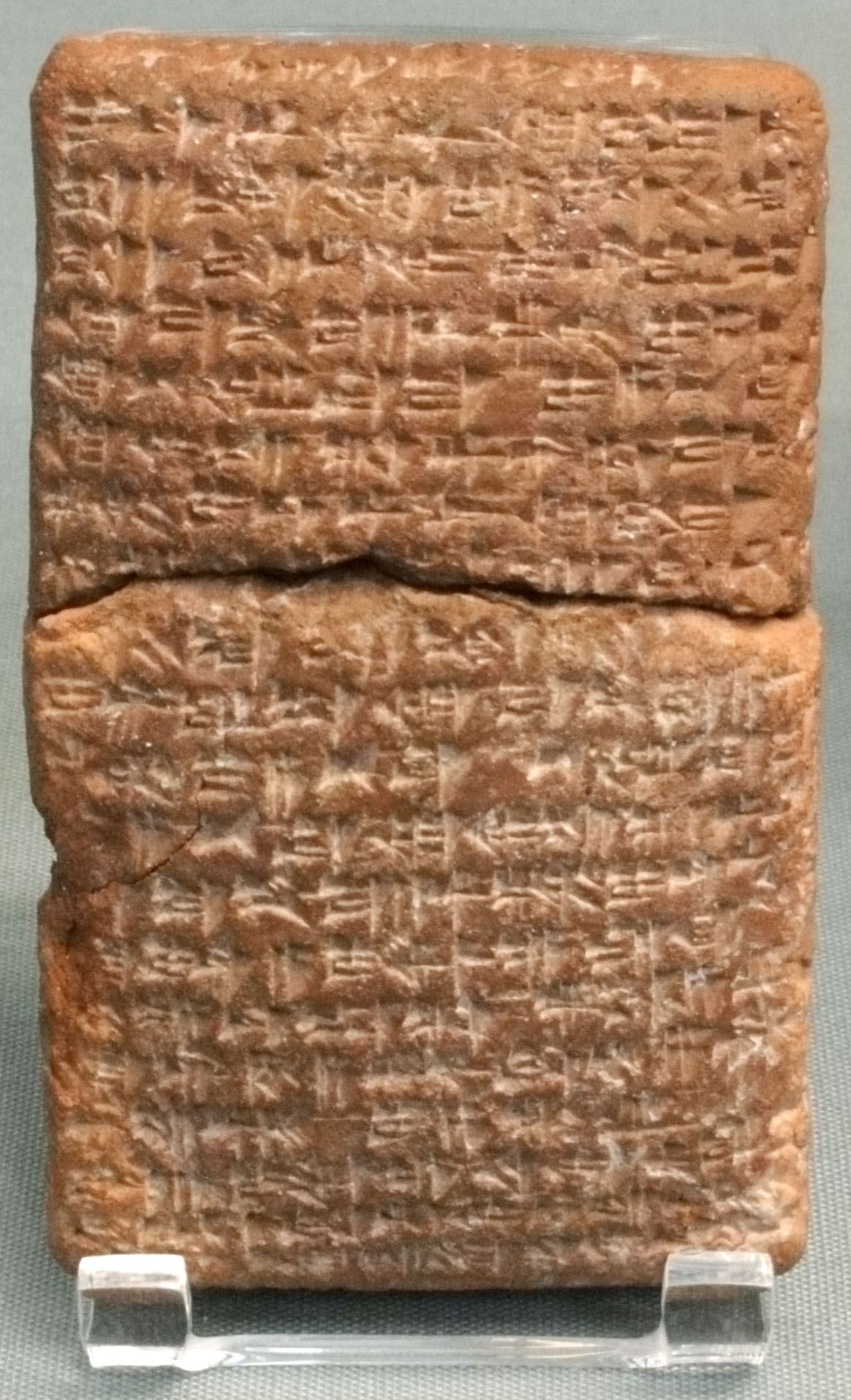

The Sumerian kingCode of Ur-Nammu

The Code of Ur-Nammu is the oldest known law code surviving today. It is from Mesopotamia and is written on tablets, in the Sumerian language c. 2100–2050 BCE.

Discovery

The first copy of the code, in two fragments found at Nippur, in what is ...

includes laws relating to slaves, written circa 2100 – 2050 BCE; it is the oldest known tablet containing a law code surviving today. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian, purportedly by Hamm ...

, dating to c. 1700 BCE, also makes distinctions between the freeborn, freed and slave.

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, slaves were mainly obtained through prisoners of war. Other ways people could become slaves was by inheriting the status from their parents. One could also become a slave on account of his inability to pay his debts. Slavery was the direct result of poverty. People also sold themselves into slavery because they were poor peasants and needed food and shelter. Slaves only attempted escape when their treatment was unusually harsh. For many, being a slave in Egypt made them better off than a freeman elsewhere. Young slaves could not be put to hard work and had to be brought up by the mistress of the household. Not all slaves went to houses. Some also sold themselves to temples or were assigned to temples by the king. Slave trading was not very popular until later in Ancient Egypt. Afterwards, slave trades sprang up all over Egypt. However, there was little worldwide trade. Rather, the individual dealers seem to have approached their customers personally. Only slaves with special traits were traded worldwide. Prices of slaves changed with time. Slaves with a special skill were more valuable than those without one. Slaves had plenty of jobs that they could be assigned to. Some had domestic jobs, like taking care of children, cooking, brewing, or cleaning. Some were gardeners or field hands in stables. They could be craftsmen or even get a higher status. For example, if they could write, they could become a manager of the master's estate. Captive slaves were mostly assigned to the temples or a king, and they had to do manual labor. The worst thing that could happen to a slave was being assigned to the quarries and mines. Private ownership of slaves, captured in war and given by the king to their captor, certainly occurred at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE). Sales of slaves occurred in theTwenty-fifth Dynasty

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXV, alternatively 25th Dynasty or Dynasty 25), also known as the Nubian Dynasty, the Kushite Empire, the Black Pharaohs, or the Napatans, after their capital Napata, was the last dynasty of th ...

(732–656 BCE), and contracts of servitude survive from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXVI, alternatively 26th Dynasty or Dynasty 26) dynasty was the last native dynasty to rule Egypt before the Persian conquest in 525 BC (although others followed). The dynasty's reign (664–525 ...

(c. 672 – 525 BCE) and from the reign of Darius

Darius may refer to:

Persian royalty

;Kings of the Achaemenid Empire

* Darius I (the Great, 550 to 487 BC)

* Darius II (423 to 404 BC)

* Darius III (Codomannus, 380 to 330 BC)

;Crown princes

* Darius (son of Xerxes I), crown prince of Persia, ma ...

: apparently such a contract then required the consent of the slave.

Ancient Judaism (the Bible)

In theJewish Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent

Old Oligarch, Constitution of the Athenians

. Pausanias (writing nearly seven centuries after the event) states that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the Battle of Marathon, and the monuments memorialize them. Spartan serfs, Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

# slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

# a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

* House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

* Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

* Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

* War-captives (''andrapoda'') who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '' penestae'' in

Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

# slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

# a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

* House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

* Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

* Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

* War-captives (''andrapoda'') who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '' penestae'' in

''

Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

), there are many references to slaves, giving rules for how they should behave and be treated. Slavery is viewed as routine, an ordinary part of society. Male Israelite

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

slaves were to be released, and well provided for, after six years of service. Non-Hebrew slaves and their offspring were the perpetual property of the owner's family, with limited exceptions. In the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, slaves are told to obey their owners.

In the debate over slavery in England and the United States in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, both supporters of slavery and abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

cited the Bible as support for their views.

Ancient Greece

The study of slavery in Ancient Greece remains a complex subject, in part because of the many different levels of servility, from traditional chattel slave through various forms ofserfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, such as helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

, penestai

The penestai or penestae (Greek: oἱ πενέσται, ''hoi penéstai'') were a class of unfree labourers in Thessaly, Ancient Greece. These labourers were tied to the land they inhabited, comparable in status with the Spartan helots.

Status

T ...

, and several other classes of non-citizens.

Most philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

s of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

defended slavery as a natural and necessary institution. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

believed that the practice of any manual or banausic

''Banausos'' (Ancient Greek , plural , ''banausoi'') is a pejorative applied to the class of manual laborers or artisans in Ancient Greece. The related abstract noun – ''banausia'' is defined by Hesychius as "every craft () onductedby me ...

job should disqualify the practitioner from citizenship. Quoting Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

, Aristotle declared all non-Greeks slaves by birth, fit for nothing but obedience.

By the late 4th century BCE passages start to appear from other Greeks, especially in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, which opposed slavery and suggested that every person living in a city-state had the right to freedom subject to no one, except those laws decided using majoritarianism

Majoritarianism is a traditional political philosophy or agenda that asserts that a majority (sometimes categorized by religion, language, social class, or some other identifying factor) of the population is entitled to a certain degree of prim ...

. Alcidamas

Alcidamas ( grc-gre, Ἀλκιδάμας), of Elaea, in Aeolis, was a Greek sophist and rhetorician, who flourished in the 4th century BC.

Life

He was the pupil and successor of Gorgias and taught at Athens at the same time as Isocrates, to wh ...

, for example, said: "God has set everyone free. No one is made a slave by nature." Furthermore, a fragment of a poem of Philemon also shows that he opposed slavery.

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s, each with its own laws. All of them permitted slavery, but the rules differed greatly from region to region. Greek slaves had some opportunities for emancipation, though all of these came at some cost to their masters. The law protected slaves, and though a slave's master had the right to beat him at will, a number of moral and cultural limitations existed on excessive use of force by masters.

In Ancient Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, about 30% of the population were slaves. The system in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

encouraged slaves to save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves—if a person struck an apparent slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It startled other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slavesOld Oligarch, Constitution of the Athenians

. Pausanias (writing nearly seven centuries after the event) states that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the Battle of Marathon, and the monuments memorialize them. Spartan serfs,

Helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

, could win freedom through bravery in battle. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

mentions that during the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

Athenians did their best to save their "women, children and slaves".

On the other hand, much of the wealth of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

came from its silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

mines at Laurion, where slaves, working in extremely poor conditions, produced the greatest part of the silver (although recent excavations seem to suggest the presence of free workers at Laurion). During the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

between Athens and Sparta, twenty thousand Athenian slaves, including both mine-workers and artisans, escaped to the Spartans when their army camped at Decelea in 413 BC.

Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

# slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

# a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

* House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

* Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

* Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

* War-captives (''andrapoda'') who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '' penestae'' in

Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

# slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

# a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

* House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

* Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

* Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

* War-captives (''andrapoda'') who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called '' penestae'' in Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

and helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

s in Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

. Penestae and helots did not rate as chattel slaves; one could not freely buy and sell them.

The comedies of Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

show how the Athenians preferred to view a house-slave

A house slave was a slave who worked, and often lived, in the house of the slave-owner, performing domestic labor. House slaves performed largely the same duties as all domestic workers throughout history, such as cooking, cleaning, serving meals, ...

: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. These plots were adapted by the Roman playwrights Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the gen ...

and Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

, and in the modern era influenced the character Jeeves

Jeeves (born Reginald Jeeves, nicknamed Reggie) is a fictional character in a series of comedic short stories and novels by English author P. G. Wodehouse. Jeeves is the highly competent valet of a wealthy and idle young Londoner named Bertie W ...

and ''A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

''A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum'' is a musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart.

Inspired by the farces of the ancient Roman playwright Plautus (254–184 BC), specifica ...

''.

Ancient Rome

Rome differed fromGreek city-states

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

in allowing freed slaves to become Roman citizens. After manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

, a slave who had belonged to a citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (''libertas''), including the right to vote, though he could not run for public office.Fergus Millar

Sir Fergus Graham Burtholme Millar, (; 5 July 1935 – 15 July 2019) was a British ancient historian and academic. He was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford between 1984 and 2002. He numbers among the most influ ...

, ''The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic'' (University of Michigan, 1998, 2002), pp. 23, 209. During the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, Roman military expansion was a major source of slaves. Besides manual labor, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Teachers, accountants, and physicians were often slaves. Greek slaves in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those condemned to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

See also

* History of slaveryReferences

{{Reflist