Slavery in Romania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery existed on the territory of present-day

Each of the slave categories was divided into two groups: '' vătraşi'' and '' lăieşi''; the former was a

Each of the slave categories was divided into two groups: '' vătraşi'' and '' lăieşi''; the former was a

The social prestige of a slave master was often proportional to the number and kinds of skilled slaves in his possession, outstanding cooks and embroiderers being used to symbolically demonstrate the high status of the boyar families. Good musicians, embroiderers or cooks were prized and fetched higher prices: for instance, in the first half of the 18th century, a regular slave was valued at around 20–30 lei, a cook would be 40 lei.

However, Djuvara, who bases his argument on a number of contemporary sources, also notes that the slaves were exceptionally cheap by any standard: in 1832, a contract involving the

The social prestige of a slave master was often proportional to the number and kinds of skilled slaves in his possession, outstanding cooks and embroiderers being used to symbolically demonstrate the high status of the boyar families. Good musicians, embroiderers or cooks were prized and fetched higher prices: for instance, in the first half of the 18th century, a regular slave was valued at around 20–30 lei, a cook would be 40 lei.

However, Djuvara, who bases his argument on a number of contemporary sources, also notes that the slaves were exceptionally cheap by any standard: in 1832, a contract involving the

Initially, and down to the 15th century, Roma and Tatar slaves were all grouped into self-administrating ''sălaşe'' (

Initially, and down to the 15th century, Roma and Tatar slaves were all grouped into self-administrating ''sălaşe'' (

The slavery of the Roma in bordering

The slavery of the Roma in bordering

The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843 in Wallachia, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. A year later, in 1844, Moldavian Prince

The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843 in Wallachia, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. A year later, in 1844, Moldavian Prince

The Romanian abolitionists debated on the future of the former slaves both before and after the laws were passed. This issue became interconnected with the "peasantry issue", an important goal of the being eliminating the

The Romanian abolitionists debated on the future of the former slaves both before and after the laws were passed. This issue became interconnected with the "peasantry issue", an important goal of the being eliminating the

"Comisia pentru Studierea Robiei Romilor – la prima întâlnire, în faţă abordării unui subiect controversat"

press release of the

*Sam Beck, "The Origins of Gypsy Slavery in Romania", in ''Dialectical Anthropology'', Volume 14, Number 1 / March, 1989, Springer Science+Business Media, Springer, p. 53-61 *V. Costăchel,

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

from the founding of the principalities of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

in 13th–14th century, until it was abolished in stages during the 1840s and 1850s before the independence of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia ( ro, Principatele Unite ale Moldovei și Țării Românești), commonly called United Principalities, was the personal union of the Principality of Moldavia and the Principality of Wallachia, ...

was allowed, and also until 1783, in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

and Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

(parts of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

). Most of the slaves were of Romani (Gypsy) ethnicity. Particularly in Moldavia there were also slaves of Tatar

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

ethnicity, probably prisoners captured from the wars with the Nogai and in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

.

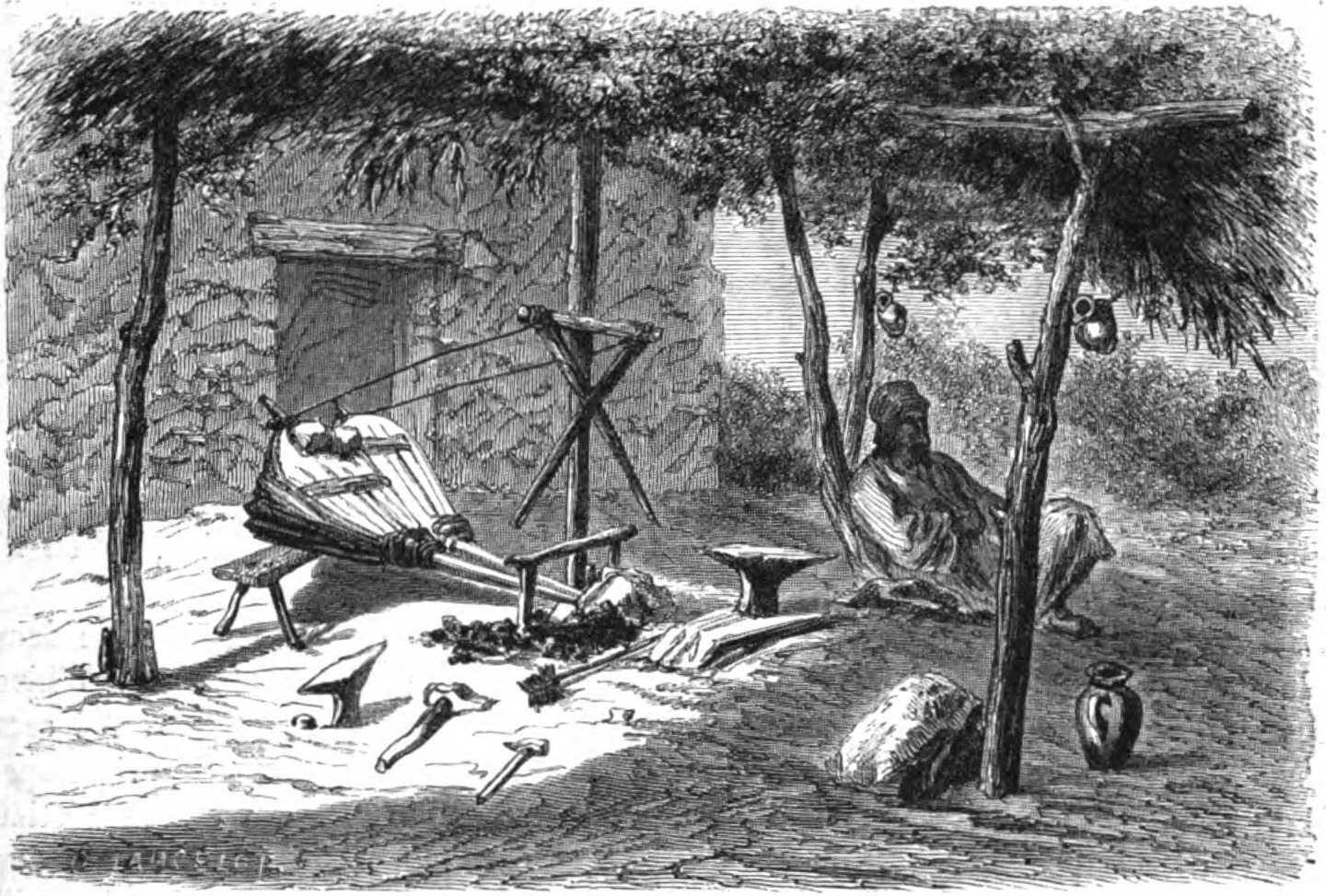

Romani slaves belonged to boyars (aristocrats), Orthodox monasteries, or the state. They were used as blacksmiths, goldsmiths and agricultural workers, but when the principalities were urbanized, they also served as servants.

The abolition of slavery was achieved at the end of a campaign by young revolutionaries influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment. Mihail Kogălniceanu, who drafted the legislation on the abolition of slavery in Moldova, remains the name associated with the abolition. In 1843, the Wallachian state freed its slaves, and in 1856, in both principalities, slaves of all classes were freed. Many Romani people in Romania

Romani people (Roma; Romi, traditionally '' Țigani'', (often called "Gypsies" though this term is considered a slur) constitute one of Romania's largest minorities. According to the 2011 census, their number was 621.573 people or 3.3% of the ...

went to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and became the Romani Americans

It is estimated that there are one million Romani people in the United States. Though the Romani population in the United States has largely assimilated into American society, the largest concentrations are in Southern California, the Pacific ...

After the abolition, there were attempts (both by the state and by private individuals) to settle the nomads and to integrate the Roma into Romanian society, but their success was limited.

Origins

The exact origins of slavery in theDanubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th c ...

are not known. Historian Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

associated the Roma people's arrival with the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe

From the 1220s into the 1240s, the Mongols conquered the Turkic states of Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, Alania, and the Kievan Rus' federation. Following this, they began their invasion into heartland Europe by launching a two-pronged invasion of ...

and through the Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe

For over three centuries, the military of the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde conducted slave raids primarily in lands controlled by Russia and Poland-Lithuania as well as other territories, often under the sponsorship of the Ottoman Empire ...

, taking the Roma from the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

as slaves and preserving their status.Achim (2004), p.27-28 Other historians consider that they were enslaved while captured during the battles with the Tatars. The practice of enslaving prisoners may also have been taken from the Mongols. The ethnic identity of the "Tatar slaves" is unknown, they could have been captured Tatars of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

, Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

, or the slaves of Tatars and Cumans.

While it is possible that some Romani people were slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars, the bulk of them came from south of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

at the end of the 14th century, some time after the foundation of Wallachia

The founding of Wallachia ( ro, descălecatul Țării Românești), that is the establishment of the first independent Romanian principality, was achieved at the beginning of the 14th century, through the unification of smaller political units th ...

. By then, the institution of slavery was already established in Moldavia, at the time enslaving the ''rumani'', but the arrival of the Roma made slavery a widespread practice. The Tatar slaves, smaller in numbers, were eventually merged into the Roma population.

Roma historian Viorel Achim also explained that "slavery was not a phenomenon characteristic only of Wallachia and Moldavia. In the Middle Ages there were slaves in neighboring countries: the Byzantine Empire, and in the Ottoman Empire, and in the Slavic countries south of the Danube. Moreover, slavery in our country is older than the arrival of gypsies. It is known about Tatar slaves, for example, who are older than Gypsy slaves, and for a time there were two well-defined categories even from a legal point of view: Tatar slaves, Gypsy slaves. But there were also Romanians who had the status of slaves."

Slavery was a common practice in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

at the time (''see Slavery in medieval Europe

Slavery, or the process of restricting peoples’ freedoms, was widespread within Medieval Europe. Europe and the Mediterranean world were part of a highly interconnected network of slave trading. Throughout Europe, wartime captives were commonly ...

''). Non-Christians in particular were taken as slaves in Christian Europe: in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

, Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

(Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

) and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

were held as slaves until they were forced to convert to Christianity in the 13th century; Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

enslaved the prisoners captured from the Tatars (''see Kholop

A kholop ( rus, холо́п, p=xɐˈlop) was a type of feudal serf in Kievan Rus', then in Russia between the 10th and early 18th centuries. Their legal status was close to that of slaves.

Etymology

The word ''kholop'' was first mentioned in ...

''), but their status eventually merged with the one of the serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

.

Christians from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

were enslaved by the Crimean Tatar Khanate, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the Nogai Horde

The Nogai Horde was a confederation founded by the Nogais that occupied the Pontic–Caspian steppe from about 1500 until they were pushed west by the Kalmyks and south by the Russians in the 17th century. The Mongol tribe called the Manghuds co ...

.

There is some debate over whether the Romani people came to Wallachia and Moldavia as slaves or not. In the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, they were slaves of the state in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

until their social organization was destroyed by the Ottoman conquest, which would suggest that they came as slaves who had a change of "ownership".Achim (2004), p.29-30 The alternative explanation, proposed by Romanian scholar P. P. Panaitescu

Petre P. Panaitescu (March 11, 1900 – November 14, 1967) was a Romanian literary historian. A native of Iași, he spent most of his adult life in the national capital Bucharest, where he rose to become a professor at University of Bucharest, ...

, was that following the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, an important east–west trade route passed through the Romanian states and the local feudal lords enslaved the Roma for economic gain for lack of other craftsmen. However, this theory is undermined by the fact that slavery was present before the trade route gained importance.

A legend tells that the Roma came to the Romanian Principalities at the invitation of Moldavian ruler Alexander the Good

Alexander the Good ( ro, Alexandru cel Bun or ''Alexandru I Mușat''; c. 1375 – 1 January 1432) was a Voivode (Lord) of Moldavia, reigning between 1400 and 1432, son of Roman I Mușat. He succeeded Iuga to the throne, and, as a ruler, ini ...

, who granted in a 1417 charter "land and air to live, and fire and iron to work", but the earliest reference to it is found in Mihail Kogălniceanu's writings and no charter was ever found.

Historian Djuvara argues forward hypotheses concerning the origin of the Romanians

Several theories address the issue of the origin of the Romanians. The Romanian language descends from the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in the Roman provinces north of the "Jireček Line" (a proposed notional line separating the predominantly ...

, such as advancing the theory that the vast majority of the nobility in the medieval states that made up the territory of modern-day Romania was of Cuman

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many sough ...

origin and not romanian: "''Romanians were called the black cumans''".(in Romanian) Eugen Istodor, "Revoluția lui Djuvara: „Românii erau numiți cumanii negri" ", interview with Neagu Djuvara in Cotidianul

The logo used between 2003 and 2007

''Cotidianul'' (meaning ''The Daily'' in English) is a Romanian language newspaper published in Bucharest, Romania.

History and profile

Founded by Ion Raţiu, ''Cotidianul'' was first published on 10 May ...

, retrieved June 19, 2007

The very first document attesting the presence of Roma people in Wallachia dates back to 1385, and refers to the group as ''aţigani'' (from ''athinganoi The ''Athinganoi'' ( grc, Ἀθίγγανοι, singular ''Athinganos'', , Atsinganoi), were a Manichean sect regarded as Judaizing heretics who lived in Phrygia and Lycaonia but were neither Hebrews nor Gentiles. They kept the Sabbath, but were not ...

'', a Greek-language word for "heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

", and the origin of the Romanian term ''ţigani'', which is synonymous with "Gypsy"). The document, signed by Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. ...

Dan I, assigned 40 ''sălaşe'' (hamlets or dwellings) of ''aţigani'' to Tismana Monastery, the first of such grants to be recorded.Ştefănescu, p.42 In Moldavia, the institution of slavery was attested to for the first time in a 1470 Moldavian document, through which Moldavian Prince Stephan the Great

Stephen III of Moldavia, most commonly known as Stephen the Great ( ro, Ștefan cel Mare; ; died on 2 July 1504), was Voivode (or Prince) of Moldavia from 1457 to 1504. He was the son of and co-ruler with Bogdan II, who was murdered in 1451 i ...

frees Oană, a Tatar slave who had fled to Jagiellon Poland

The rule of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Poland between 1386 and 1572 spans the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period in European history. The Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) founded the dynasty; his marriage ...

.Achim (2004), p.36

Anthropologist Sam Beck argues that the origins of Roma slavery can be most easily explained in the practice of taking prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

as slaves, a mongol practice with a long history in the region, and that, initially, free and enslaved Roma coexisted on what became Romanian territory.Beck, p.56

There are some accounts according to which some of the Roma slaves had been captured during wars. For instance, in 1445, Vlad Dracul

Vlad II ( ro, Vlad al II-lea), also known as Vlad Dracul () or Vlad the Dragon (before 1395 – November 1447), was Voivode of Wallachia from 1436 to 1442, and again from 1443 to 1447. He is internationally known as the father of Vlad the Impa ...

took by force from Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

to Wallachia around 11,000-12,000 people "who looked like Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

", presumably Roma.

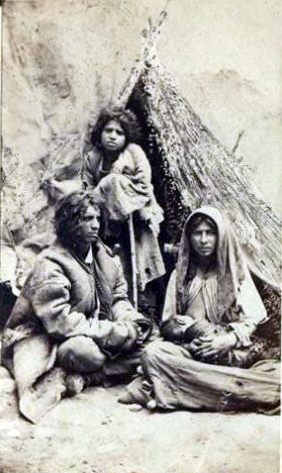

Condition of the slaves

General characteristics and slave categories

TheDanubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th c ...

were for most of their history the only territory in Eastern and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

where Roma slavery was legislated, and the place where this was most extended.Guy, p.44 As a consequence of this, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

sociologist Will Guy describes Romania as a "unique case", and one of the fort main "patterns of development" in what concerns the Roma groups of the region (alongside those present in countries that have in the recent past belonged to the Ottomans, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

).

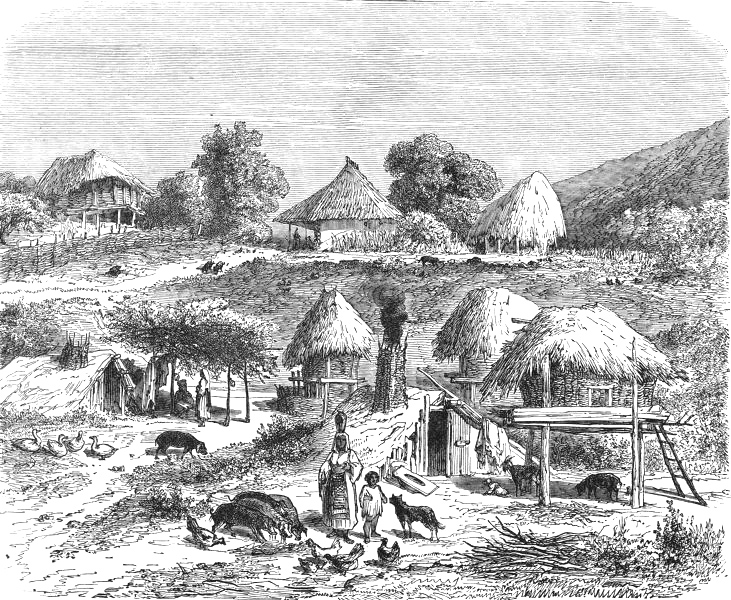

Traditionally, Roma slaves were divided into three categories. The smallest was owned by the ''hospodars'', and went by the Romanian-language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește'', ) is the official and main language of Romania and the Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communities in t ...

name of ''ţigani domneşti'' ("Gypsies belonging to the lord"). The two other categories comprised ''ţigani mănăstireşti'' ("Gypsies belonging to the monasteries"), who were the property of Romanian Orthodox

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; ro, Biserica Ortodoxă Română, ), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates ...

and Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

monasteries, and ''ţigani boiereşti'' ("Gypsies belonging to the boyars"), who were enslaved by landowners. The status of the ''ţigani domneşti'' was better than the one of the slaves held by boyars or the monasteries and many slaves given by the Prince to private owners or to monasteries ran away and joined the communities of the Prince's slaves.Marushiakova and Vesselin, p. 103

Each of the slave categories was divided into two groups: '' vătraşi'' and '' lăieşi''; the former was a

Each of the slave categories was divided into two groups: '' vătraşi'' and '' lăieşi''; the former was a sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

category, while the latter was allowed to preserve its nomadism

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

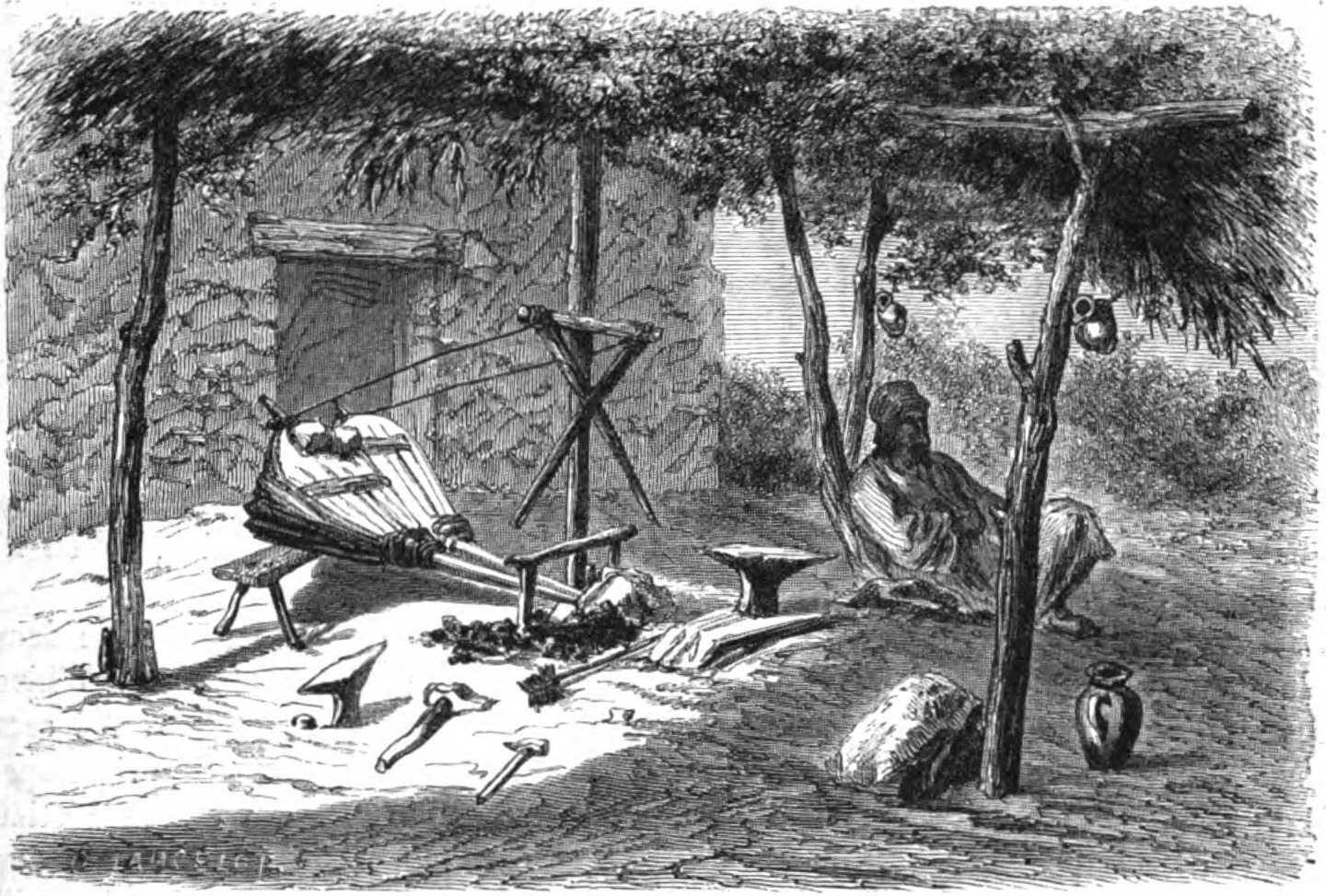

. The ''lăieşi'' category comprised several occupational subgroups: alongside the Kalderash (''căldărari'' or "copper workers"), '' Lăutari'' ("string instrument players"), Boyash

Boyash or ''Bayash'' (endonym: ''Bȯjáṡ'', Romanian: ''Băieși'', Hungarian: ''Beás'', Slovak: ''Bojáš'', South Slavic: ''Bojaši'') refers to a Romani ethnic group living in Romania, southern Hungary, northeastern and northwestern ...

(''lingurari'' or "spoon makers") and Ursari

The Ursari (generally read as " bear leaders" or "bear handlers"; from the ro, urs, meaning "bear"; singular: ''ursar''; Bulgarian: урсари, ''ursari'') or Richinara are the traditionally nomadic occupational group of animal trainers amo ...

("bear handlers"), all of which developed as distinct ethic subgroups, they comprised the ''fierari'' ("smiths"). For a long period of time, the Roma were the only smiths and ironmongers in Wallachia and Moldavia. Among the ''fierari'', the more valued were the specialized ''potcovari'' ("farriers

A farrier is a specialist in equine hoof care, including the trimming and balancing of horses' hooves and the placing of shoes on their hooves, if necessary. A farrier combines some blacksmith's skills (fabricating, adapting, and adjus ...

"). Women owned by the boyars were often employed as housemaids in service to the boyaresses,Djuvara, p.268 and both them and some of the enslaved men could be assigned administrative tasks within the manor. From early on in the history of slavery in Romania, many other slaves were made to work in the salt mines.

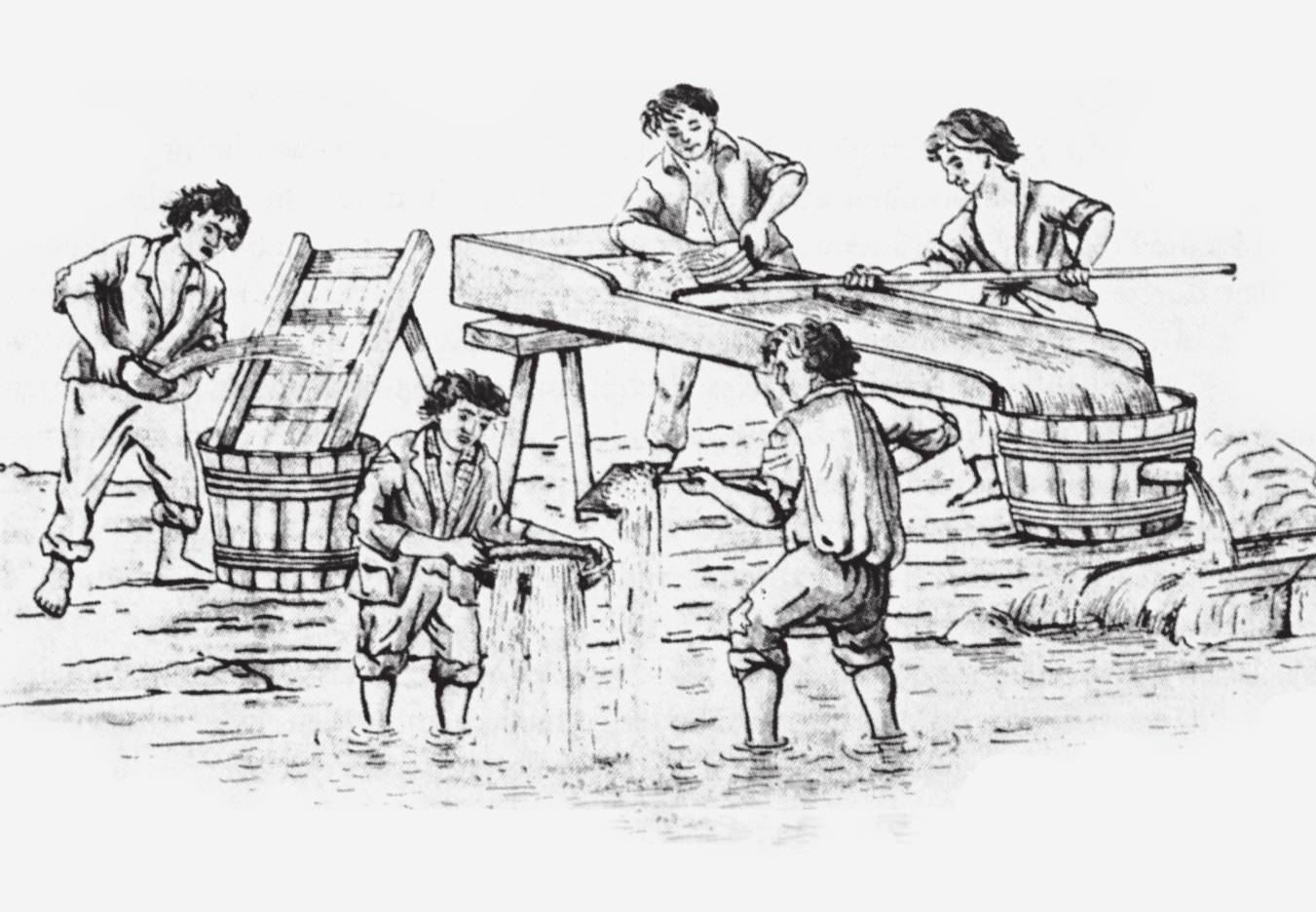

Another category was the '' Aurari'' or '' Rudari'' (gold miner

Gold mining is the extraction of gold resources by mining. Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. However, with the expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface ...

s), who were slaves of the Prince who panned for gold during the warm season in the mountain rivers of the Carpathians, while staying in the plains during the winter, carving wooden utensils. The gold miners, through their yield of gold, brought much more income to the treasury than the other types of slaves and initially they were in large numbers, but as the deposits became exhausted, their number dropped. By 1810, there were only 400 Aurari panning for gold in Wallachia.

During the 14th and 15th centuries very few slaves were found in the cities. Only since the beginning of the 16th century, monasteries began opening in the cities and they brought with them the Roma slaves and soon boyars and even townfolks began to use them for various tasks.Laurenţiu Rădvan, ''At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities'', Brill, 2010, p.213 The ''sălaşe'' of Roma slaves were settled in the outskirts, and soon, almost all cities had such a district, with the largest being in the largest cities, including Târgoviște

Târgoviște (, alternatively spelled ''Tîrgoviște''; german: Tergowisch) is a city and county seat in Dâmbovița County, Romania. It is situated north-west of Bucharest, on the right bank of the Ialomița River.

Târgoviște was one of ...

, Râmnic

The Râmnic is a left tributary of the river Casimcea in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hu ...

or Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

.

Medieval society allowed a certain degree of social mobility, as attested by the career of Ştefan Răzvan, a Wallachian Roma slave who was able to rise to the rank of boyar, was sent on official duty to the Ottoman Empire, and, after allying himself with the Poles and Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

groups, became Moldavian Prince (April–August 1595).

Status and obligations

The Roma were considered personal property of the boyar, who was allowed to put them to work, selling them or exchanging them for other goods and the possessions of the slaves were also at the discretion of the master, this form of slavery distinguishing itself from the ''rumâni'', who could only be sold together with the land. The boyar was allowed to punish his slaves physically, through beatings or imprisonment, but he or she did not have power of life and death over them, the only obligation of the master being to clothe and feed the slaves who worked at his manor. The social prestige of a slave master was often proportional to the number and kinds of skilled slaves in his possession, outstanding cooks and embroiderers being used to symbolically demonstrate the high status of the boyar families. Good musicians, embroiderers or cooks were prized and fetched higher prices: for instance, in the first half of the 18th century, a regular slave was valued at around 20–30 lei, a cook would be 40 lei.

However, Djuvara, who bases his argument on a number of contemporary sources, also notes that the slaves were exceptionally cheap by any standard: in 1832, a contract involving the

The social prestige of a slave master was often proportional to the number and kinds of skilled slaves in his possession, outstanding cooks and embroiderers being used to symbolically demonstrate the high status of the boyar families. Good musicians, embroiderers or cooks were prized and fetched higher prices: for instance, in the first half of the 18th century, a regular slave was valued at around 20–30 lei, a cook would be 40 lei.

However, Djuvara, who bases his argument on a number of contemporary sources, also notes that the slaves were exceptionally cheap by any standard: in 1832, a contract involving the dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

of a boyaress shows that thirty Roma slaves were exchanged for one carriage, while the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

diplomat William Wilkinson noted that the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was a semi-clandestine matter, and that ''vătraşi'' slaves could fetch the modest sum of five or six hundred Turkish kuruş

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

.Djuvara, p.270 According to Djuvara's estimate, ''lăieşi'' could be worth only half the sum attested by Wilkinson.

In the Principalities, the slaves were governed by common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

. By the 17th century, the earliest written laws to mention slavery appeared. The Wallachian ' (1640) and ' (1652) and the Moldavian '' Carte Românească de Învăţătură'' (1646), which, among other things, regulated slavery, were based on the Byzantine law

Byzantine law was essentially a continuation of Roman law with increased Orthodox Christian and Hellenistic influence. Most sources define ''Byzantine law'' as the Roman legal traditions starting after the reign of Justinian I in the 6th century ...

on slavery and on the common law then in use. However, customary law (''obiceiul pământului'') was almost always used in practice.

If a slave owned property, one would have to pay the same taxes as the free men. Usually, there was no tax on privately owned slaves, excepting for a short period in Moldavia: between 1711 and 1714, Phanariote Prince Nicholas Mavrocordatos

Nicholas Mavrocordatos ( el, Νικόλαος Μαυροκορδάτος, ro, Nicolae Mavrocordat; May 3, 1670September 3, 1730) was a Greek member of the Mavrocordatos family, Grand Dragoman to the Divan (1697), and consequently the first P ...

introduced the ''ţigănit'' ("Gypsy tax"), a tax of two ''galbeni'' (standard gold coins) on each slave owned.Achim (2004), p.37 It was not unusual for both boyars and monasteries to register their serfs as "Gypsies" so that they would not pay the taxes that were imposed on the serfs.

The ''domneşti'' slaves (some of whom were itinerant artisans), would have to pay a yearly tax named ''dajdie''. Similarly, boyar-owned ''lăieşi'' were required to gather at their master's household once a year, usually on the autumn feast of Saint Demetrius

Saint Demetrius (or Demetrios) of Thessalonica ( el, Ἅγιος Δημήτριος τῆς Θεσσαλονίκης, (); bg, Димитър Солунски (); mk, Свети Димитрија Солунски (); ro, Sfântul Dumitru; sr ...

(presently coinciding with the October 26 celebrations in the Orthodox calendar). On the occasion, each individual over the age of 15 was required to pay a sum of between thirty and forty piastres.

A slaveowner had the power to free his slaves for good service, either during his lifetime or in his will, but these cases were rather rare. The other way around also happened: free Roma sold themselves to monasteries or boyars in order to make a living.

Legal disputes and disruption of the traditional lifestyles

Initially, and down to the 15th century, Roma and Tatar slaves were all grouped into self-administrating ''sălaşe'' (

Initially, and down to the 15th century, Roma and Tatar slaves were all grouped into self-administrating ''sălaşe'' (Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and othe ...

: челѣдь, ''čelyad'') which were variously described by historians as being an extended family

An extended family is a family that extends beyond the nuclear family of parents and their children to include aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins or other relatives, all living nearby or in the same household. Particular forms include the stem ...

, a household or even a community. Their leaders, themselves slaves, were known as '' cneji'', '' juzi'' or '' vătămani'', and, in addition to sorting legal disputes, collected taxes and organised labour for the owners. With time, disputes between two Roma slaves were usually dealt by the community leaders, who became known as '' bulibaşi''. Occasionally, the larger slave communities elected themselves a ''başbulibaşa'', who was superior to the ''bulibaşi'' and charged with solving the more divisive or complicated conflicts within the respective group.Djuvara, p.269 The system went unregulated, often leading to violent conflicts between slaves, which, in one such case attested for the 19th century, led to boyar intervention and the foot whipping

Foot whipping, falanga/falaka or bastinado is a method of inflicting pain and humiliation by administering a beating on the soles of a person's bare feet. Unlike most types of flogging, it is meant more to be painful than to cause actual injury ...

of those deemed guilty of insubordination.

The disputes with non-slaves and the manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

cases were dealt by the state judiciary system. Slaves were not allowed to defend themselves or bear witness in front of a court, but they were also not responsible to damage done to free men, the owner being accountable for any such damages, the compensation being sometimes the renunciation of the ownership of the slave to the other party. A slave who killed another slave was sentenced to death, but they could also be given to the owner of the dead slave. A freeman killing a slave was also liable for death penalty and a boyar was not allowed to kill his own slaves, but no such sentencing is attested. It is, however, believed that such killings did occur in significant numbers.Ştefănescu, p.43

The Orthodox Church, itself a major slaveholder, did not contest the institution of slavery, although among the early advocates of the abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

*Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

* Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

*Abolition of monarchy

*Abolition of nuclear weapons

*Abolit ...

was Eufrosin Poteca

Eufrosin Poteca (; born Radu Poteca; 1786 – 10 December 1858) was a Romanian philosopher, theologian, and translator, professor at the Saint Sava Academy of Bucharest. Later in life he campaigned against slavery. He was the grandfather of the ...

, a priest. Occasionally, members of the church hierarchy intervened to limit abuse against slaves it did not own: Wallachian Metropolitan Dositei demanded from Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. ...

Constantine Ypsilantis

Constantine Ypsilantis ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Υψηλάντης ''Konstantinos Ypsilantis''; ro, Constantin Ipsilanti; 1760 – 24 June 1816), was the son of Alexander Ypsilantis, a key member of an important Phanariote family, G ...

to discourage his servants from harassing a young Roma girl named Domniţa. The young woman was referred to as one of the ''domneşti'' slaves, although she had been freed by that moment.Djuvara, p.271

Like many of the serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

in the two principalities, slaves were prone to escape from the estates and seek a better life on other domains or abroad, which made boyars organize search parties and make efforts to have them return. Fugitive slaves would settle abroad in Hungary, Poland, lands of the Cossacks, the Ottoman Empire, Serbia, or from Moldavia to Wallachia and the other way around.Costăchel ''et al.'', p.162 The administrations of the two states supported the search and return of fugitive slave

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

s to their masters. Occasionally, the hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or " master".

Etymology and Slavic usage

In the Slavonic language, ''hospodar'' is usually applied to the master/owner of a house or other properties and also the head of a family. ...

s organized expeditions abroad in order to find runaways, or through diplomacy, they appealed to the rulers of the lands where the runaways settled. For instance, in 1570, ''logofăt Logothete ( el, λογοθέτης, ''logothétēs'', pl. λογοθέται, ''logothétai''; Med. la, logotheta, pl. ''logothetae''; bg, логотет; it, logoteta; ro, logofăt; sr, логотет, ''logotet'') was an administrative title ...

'' Drăgan was sent by Bogdan IV of Moldavia

Bogdan IV of Moldavia (9 May 1555 – July 1574) was Prince of Moldavia from 1568 to 1572. He succeeded to the throne as son of the previous ruler, Alexandru Lăpușneanu

Alexandru IV Lăpușneanu (1499 – 5 May 1568) was Ruler of Moldavia bet ...

to the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

to ask for the return of 13 ''sălaşe'' of slaves.

In the 16th century, the duties of collecting wartime tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

s and of retrieving runaways were performed by a category called ''globnici'', many of whom were also slaves. Beginning in the 17th century, much of the Kalderash population left the region to settle south into the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, and later also moved into other regions of Europe.

A small section of the native Roma population managed to evade the system (either by not having been originally enslaved as a group, or by regrouping runaway slaves). They lived in isolation on the margin of society, and tended to settle in places where access was a problem. They were known to locals as ''netoţi'' (lit. "incomplete ones", a dismissive term generally used to designate people with mental disorder

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

s or who display poor judgment). Around 1830, they became the target of regular manhunts, those captured being turned into ''ţigani domneşti''.

A particular problem regarded the '' vătraşi'', whose lifestyle was heavily disrupted by forced settlement and the requirement that they perform menial labour. Traditionally, this category made efforts to avoid agricultural work in service of their masters. Djuvara argues that this was because their economic patterns were at a hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

stage. Christine Reinhard, an early 19th-century intellectual and wife of French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

diplomat Charles-Frédéric Reinhard

Charles-Frédéric, '' comte'' Reinhard (born Karl Friedrich Reinhard; 2 October 1761 – 25 December 1837) was a Württembergian-born French diplomat, essayist, and politician who briefly served as the Consulate's Minister of Foreign Affairs in 17 ...

, recorded that, in 1806, a member of the Moldavian Sturdza family

The House of Sturdza, Sturza or Stourdza is the name of an old Moldavian noble family, whose origins can be traced back to the 1540s and whose members played important political role in the history of Moldavia, Russia and later Romania.

Political ...

employed a group of ''vătraşi'' at his factory. The project was reputedly abandoned after Sturdza realised he was inflicting intense suffering on his employees.

Roma artisans were occasionally allowed to practice their trade outside the boyar household, in exchange for their own revenue. This was the case of ''Lăutari'', who were routinely present at fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s and in public houses as independent '' tarafs''. Slaves could own a number of bovines, but part of their other forms of revenue was collected by the master. In parallel, the ''lăieşi'' are believed to have often resorted to stealing the property of peasants. According to Djuvara, Roma housemaids were often spared hard work, especially in cases where the number of slaves per household ensured a fairer division of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, an ...

.

Marriage regulations

Marriage between two slaves was only allowed with the approval of the two owners, usually through a financial agreement which resulted in the selling of one slave to the other owner or through an exchange.Achim (2004), p.38-39; Djuvara, p.268 When no agreement was reached, the couple was split and the children resulting from the marriage were divided between the two slaveholders. Slave owners kept strict records of their ''lăieşi'' slaves, and, according to Djuvara, were particularly anxious because the parents of slave children could sell their offspring to other masters. The slaveowners separated Roma couples when selling one of the spouses. This practice was banned byConstantine Mavrocordatos

Constantine Mavrocordatos (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Μαυροκορδάτος, Romanian: ''Constantin Mavrocordat''; February 27, 1711November 23, 1769) was a Greek noble who served as Prince of Wallachia and Prince of Moldavia at several ...

in 1763 and discouraged by the Orthodox Church, which decreed in 1766 that "although they are called gypsies .e. slaves the Lord created them and it is indecent to separate them like cattle".Marushiakova and Vesselin, p. 99 Nevertheless, splitting married spouses was still common in the 19th century.

Marriage between a free person and a slave was initially possible only by the free person becoming a slave, although later on, it was possible for a free person to keep one's social status and that the children resulting from the marriage to be free people.

During several periods in history, this kind of intercourse was explicitly forbidden:

In Moldavia, in 1774, prince Alexander Mourousis

Alexander Mourouzis ( el, Αλέξανδρος Μουρούζης; Romanian: Alexandru Moruzi (1750/1760 – 1816) was a Grand Dragoman of the Ottoman Empire who served as Prince of Moldavia and Prince of Wallachia. Open to Enlightenment ideas ...

banned marriages between free people and slaves. A similar chrysobull

A golden bull or chrysobull was a decree issued by Byzantine Emperors and later by monarchs in Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most notably by the Holy Roman Emperors. The term was originally coined for the golden seal (a ''bull ...

was decreed by Alexandru Mavrocordat Firaris in 1785, which not only banned such marriages, but invalidated any such existing marriage.

In Wallachia, Alexander Ypsilantis

Alexandros Ypsilantis ( el, Αλέξανδρος Υψηλάντης, Aléxandros Ypsilántis, ; ro, Alexandru Ipsilanti; russian: Александр Константинович Ипсиланти, Aleksandr Konstantinovich Ipsilanti; 12 Dece ...

(1774–1782) banned mixed marriages in his law code, but the children resulting from such marriages were to be born free. In 1804, Constantine Ypsilantis ordered the forceful divorce of one such couple, and issued an order to have priests sealing this type of unions to be punished by their superiors.

Marital relations between Roma people and the majority ethnic Romanian population were rare, due to the difference in status and, as Djuvara notes, to an emerging form of racial prejudice

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

. Nevertheless, extra-marital relationships between male slave owners and female slaves, as well as the rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

of Roma women by their owners, were widespread, and the illegitimate children were themselves kept as slaves on the estate.

Transylvania, Bukovina and Bessarabia

The slavery of the Roma in bordering

The slavery of the Roma in bordering Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

was found especially in the fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

s and areas under the influence of Wallachia and Moldavia, these areas keeping their practice of slavery even after they were no longer under Wallachian or Moldavian possession.Achim (2004), p.42 The earliest record of Roma in Transylvania is from around 1400, when a boyar was recorded of owning 17 dwellings of Roma in Făgăraş, an area belong to Wallachia at the time. The social organization of Făgăraş was the same as in Wallachia, the Roma slaves being the slaves of boyars, the institution of slavery being kept in the Voivodate of Transylvania within the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

and in the autonomous Principality of Transylvania, being only abolished with the beginning of the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

domination in the 18th century. For instance, in 1556, Hungarian Queen Isabella Jagiełło

Isabella Jagiellon ( hu, Izabella királyné, links=no; pl, Izabela Jagiellonka, links=no; 18 January 1519 – 15 September 1559) was the Queen consort of Hungary. She was the oldest child of Polish King Sigismund I the Old, the Grand Duke of L ...

confirmed the possessions of some Recea boyars, which included Roma slaves. The deed was also confirmed in 1689 by Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

Michael I Apafi

Michael Apafi ( hu, Apafi Mihály; 3 November 1632 – 15 April 1690) was Prince of Transylvania from 1661 to his death.

Background

The Principality of Transylvania emerged after the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in the sec ...

.

The estates belonging to the Bran Castle

Bran Castle ( ro, Castelul Bran; german: Schloss Bran; hu, Törcsvári kastély) is a castle in Bran, southwest of Brașov. It is a national monument and landmark in Transylvania. The fortress is on the Transylvanian side of the historical bo ...

also held a large number of slaves, around 1500 at the beginning of the 16th century, the right of being a slaveholder being probably inherited from the time that the castle was owned by Wallachia.Achim (2004), p.43 Areas under the influence of Moldavia also held slaves: for instance, it is known that Moldavian Prince Petru Rareş Petru is a given name, and may refer to:

* Petru I of Moldavia (Petru Mușat, 1375–1391), ruler of Moldavia

* Petru Aron (died 1467), ruler of Moldavia

* Petru Bălan (born 1976), Romanian rugby union footballer

* Petru Cărare (1935–2019), wri ...

bought a family of Roma from the mayor of Bistriţa and that other boyars also bought slaves from Transylvania. However, only a minority of the Transylvanian Roma were slaves, most of them being "royal serfs", under the direct authority of the King, being only required to pay certain taxes and perform some services for the state, some groups of Roma being given the permission to travel freely throughout the country.

In 1775, Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

, the scene of the 1821 incidents, was annexed from Moldavia by the Habsburgs, and inherited the practice of slavery, especially since the many monasteries in the region held a large number of Roma slaves. The number of Roma living in Bukovina was estimated in 1775 at 800 families, or 4.6% of the population. Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 unt ...

issued an order abolishing slavery on June 19, 1783, in Czernowitz

Chernivtsi ( uk, Чернівці́}, ; ro, Cernăuți, ; see also other names) is a city in the historical region of Bukovina, which is now divided along the borders of Romania and Ukraine, including this city, which is situated on the up ...

, similar to other orders given throughout the Empire against slavery (''see Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

''). The order met the opposition of the large slaveholders: the Romanian Orthodox monasteries and the boyars. The boyars loudly pleaded their case to the authorities of Bukovina and Galicia, arguing that the banning of slavery was a transgression against the autonomy and traditions of the province, that bondage is the appropriate state for the Roma and that it was for their own good.Achim (2004), p.128 It took a few more years until the order was fully implemented, but toward the end of the 1780s, the slaves officially joined the ranks of the landless peasantry. Many of the "new peasants" (as they were called in some documents) remained to work for the estates for which they were slaves, the liberation bringing little immediate change in their life.

After the eastern half of Moldavia, known as Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, was annexed by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in 1812 and later set up as a Bessarabia Governorate

The Bessarabia Governorate (, ) was a part of the Russian Empire from 1812 to 1917. Initially known as Bessarabia Oblast (Бессарабская область, ''Bessarabskaya oblast'') as well as, following 1871, a governorate, it included ...

, the slave status for the Roma was kept. Slavery was legislated in the "Establishment of the organisation of the province of Bessarabia" act of 1818, by which the Roma were a social category divided into state slaves and private slaves, which belonged to boyars, clergy or traders. The Empire's authorities tried the sedentize the nomadic state slaves by turning them into serfs of the state. Two villages were created in Southern Bessarabia

Southern Bessarabia or South Bessarabia is a territory of Bessarabia which, as a result of the Crimean War, was returned to the Moldavian Principality in 1856. As a result of the unification of the latter with Wallachia, these lands became part ...

, Cair and Faraonovca (now both in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

) by settling 752 Roma families. However, things did not go as expected, the state of the villages "sank to deplorable levels" and their inhabitants refused to pay any taxes.Achim (2004), p.131 According to the 1858 census, in Bessarabia, there were 11,074 Roma slaves, of which 5,615 belonged to the state and 5,459 to the boyars. Slavery, together with serfdom, was only abolished by the emancipation laws of 1861. As a consequence, the slaves became peasants, continuing to work for their former masters or joining the nomadic Roma craftsmen and musicians.

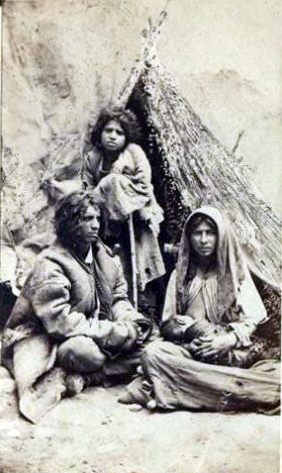

Estimates for the slave population

The Roma slaves were not included in the tax censuses and as such, there are no reliable statistics about them, the exception being the slaves owned by the state. Nevertheless, there were several 19th century estimates. According to Djuvara, the estimates for the slave population tended to gravitate around 150,000-200,000 persons, which he notes was equivalent to 10% of the two countries' population. At the time of the abolition of slavery, in the two principalities there were between 200,000 and 250,000 Roma, representing 7% of the total population.Achim (2004), p.94-95Emergence of the abolitionist movement

The moral and social problems posed by Roma slavery were first acknowledged during theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, firstly by Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

an visitors to the two countries.

The evolution of Romanian society and the abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in 1746 in Wallachia and 1749 in Moldavia had no effect on the Roma, who, in the 19th century, were subject to the same conditions they endured for centuries. It was only when the Phanariote

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumeni ...

regime was changed, soon after 1821, that Romanian society began to modernise itself and various reforms were implemented (''see Regulamentul Organic

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual na ...

''). However, the slavery of the Roma was not considered a priority and it was ignored by most reformers.

Nevertheless, the administration in the Danubian Principalities did try to change the status of the state Romas, by attempting the sedentarization of the nomads. Two annexes to ''Regulamentul Organic'' were drafted, "Regulation for Improving the Condition of State Gypsies" in Wallachia in April 1831, and "Regulation for the Settlement of Gypsies" in Moldavia. The regulations attempted to sedenterize the Romas and train them till the land, encouraging them to settle on private estates.Achim (2010), p.24

By the late 1830s, liberal and radical boyars, many of whom studied in Western Europe, particularly in Paris, had taken the first steps toward the anti-slavery goal. During that period, Ion Câmpineanu

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

, like the landowning brothers Nicolae and Ştefan Golescu, emancipated all his slave retinue,Djuvara, p.275 while boyar Emanoil Bălăceanu freed his slaves and organized for them the Scăieni Phalanstery, an utopian socialist community. In 1836, Wallachian Prince Alexandru II Ghica

Alexandru Dimitrie Ghica (1 May 1796 – January 1862), a member of the Ghica family, was Prince of Wallachia from April 1834 to 7 October 1842 and later caimacam (regent) from July 1856 to October 1858.

Family

He was son of Demetriu Ghica ...

freed 4,000 ''domneşti'' slaves and had a group of landowners sign them up as paid workforce, while instigating a policy through which the state purchased privately owned slaves and set them free.

The emancipation of slaves owned by the state and Romanian Orthodox

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; ro, Biserica Ortodoxă Română, ), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates ...

and Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

monasteries was mentioned in the programme of the 1839 confederative conspiracy of Leonte Radu in Moldavia, giving them equal rights with the Romanians. In Wallachia, a memorandum written by Mitică Filipescu

Mitică () is a fictional character who appears in several sketch stories by Romanian writer Ion Luca Caragiale. The character's name is a common hypocoristic form of ''Dumitru'' or ''Dimitrie'' (Romanian for ''Demetrius''). He is one of the bes ...

proposed to put an end to slavery by allowing the slaves to buy their own freedom.Achim (2004), p.99-100 The 1848 generation, which studied in Western Europe, particularly in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, returned to their countries with progressive views and a wish to modernize them following the West as an example. Slavery had been abolished in most of the "civilized world" and, as such, the liberal Romanian intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

viewed its slavery as a barbaric

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less ...

practice, with a feeling of shame.Achim (2004), p.98

In 1837, Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on October 11, 1863, ...

published a book on the Roma people, in which he expressed the hope that it will serve the abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. During the 1840s, the intellectuals began a campaign aimed at convincing the slaveholders to free their slaves. The Wallachian Cezar Bolliac

Cezar Bolliac or Boliac, Boliak (March 23, 1813 – February 25, 1881) was a Wallachian and Romanian radical political figure, amateur archaeologist, journalist and Romantic poet.

Life

Early life

Born in Bucharest as the son of Anton Bogliako ...

published in his '' Foaie pentru Minte, Inimă şi Literatură'' an appeal to intellectuals to support the cause of the abolitionist movement. From just a few voices advocating abolitionism in the 1830s, in the 1840s, it became a subject of great debate in Romanian society. The political power was in the hand of the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the Feudalism, feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgarian Empire, Bulgaria, Russian nobility, Russia, Boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia, Wallachia and ...

s, who were also owners of large numbers of slaves and as such disagreed to any reforms that might affect them.

Laws on abolition

The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843 in Wallachia, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. A year later, in 1844, Moldavian Prince

The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843 in Wallachia, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. A year later, in 1844, Moldavian Prince Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza (24 April 1794, Iași – 8 May 1884, Paris), sometimes anglicized as Michael Stourdza, was prince of Moldavia from 1834 to 1849. He was cousin of Roxandra Sturdza and Alexandru Sturdza.

Biography

He was son of Grigore Sturdza, se ...

proposed a law on the freeing of slaves owned by the church and state.Achim (2004), p.108-109; Djuvara, p.275 In 1847, in Wallachia, a law of Prince Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu (;April 26th 1804 – 1 June 1873) was a ''hospodar'' (Prince) of Wallachia between 1843 and 1848. His rule coincided with the revolutionary tide that culminated in the 1848 Wallachian revolution.

Early political career

Born in ...

adopted by the Divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

freed the slaves owned by the church and the rest of the slaves owned by the state institutions.

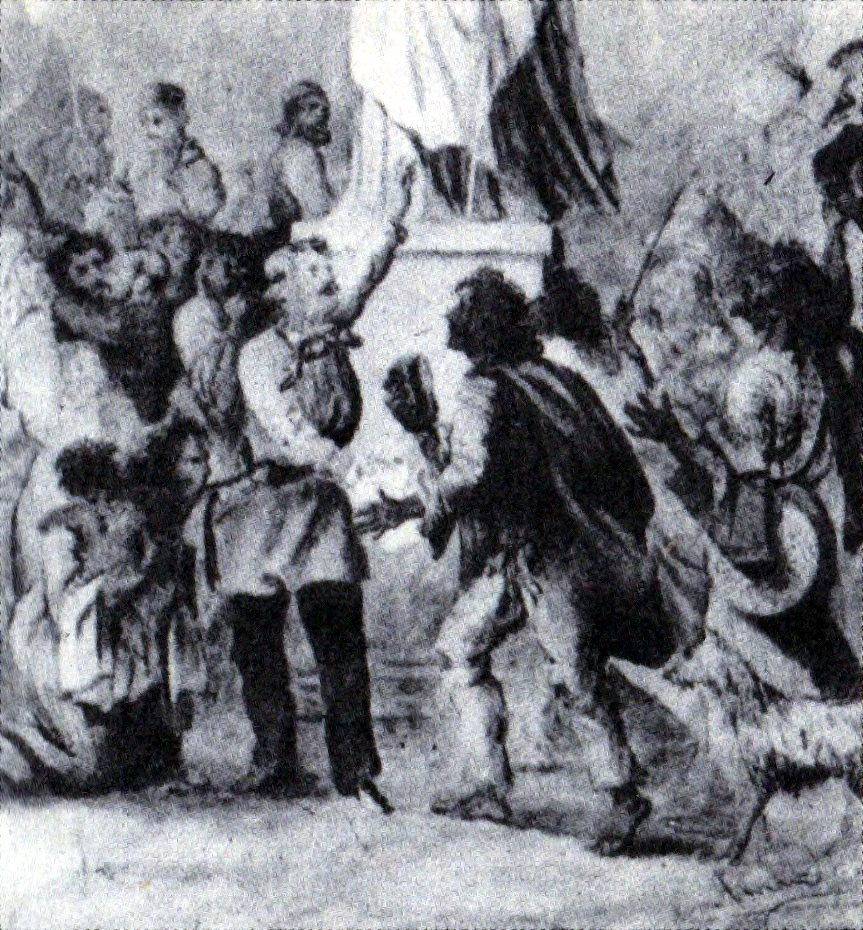

During the Wallachian Revolution of 1848

The Wallachian Revolution of 1848 was a Romanian liberal and nationalist uprising in the Principality of Wallachia. Part of the Revolutions of 1848, and closely connected with the unsuccessful revolt in the Principality of Moldavia, it sought t ...

, the agenda of the short-lived Provisional Government included the emancipation (''dezrobire'') of the Roma as one of the main social demands. The Government decreed the complete emancipation of the Roma by compensating the owners and it made a commission (made out of three members: Bolliac, Ioasaf Znagoveanu Iosafat Snagoveanu (; also credited as Ioasaf Znagoveanu, born Ion Vărbileanu ; April 22, 1797–November 3, 1872) was a Wallachian revolutionary and monk of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

Born in Prahova County, in a village on the Vărbilă ...

, and Petrache Poenaru), which was intended to implement the decree. Some boyars freed their slaves without asking for compensation, while others strongly fought against the idea of abolition. Nevertheless, after the revolution was quelled by Ottoman and Imperial Russian

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

troops, the slaves returned to their previous status.

By the 1850s, after its tenets were intensely popularized, the movement gained support from almost the whole of Romanian society, the issues of contention being the exact date of Roma freedom, and whether their owners would receive any form of compensation (a measure which the abolitionists considered "immoral").

In Moldavia, in December 1855, following a proposal by Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica

Grigore Alexandru Ghica or Ghika (1803 or 1807 – 24 August 1857) was a Prince of Moldavia between 14 October 1849, and June 1853, and again between 30 October 1854, and 3 June 1856. His wife was Helena, a member of the Sturdza family and dau ...

, a bill drafted by Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on October 11, 1863, ...

and Petre Mavrogheni

Petre Mavrogheni (November 1819 – 20 April 1887) also known as Petru Mavrogheni was a Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 11 May until 13 July 1866 and as the Minister of Finance.

Life and career

Mavroghe ...

was adopted by the Divan; the law emancipated all slaves to the status of taxpayers (that is, citizens). The measure was brought about by a personal tragedy: Ghica and the public opinion at large were scandalized when Dincă, the slave and illegitimate child of a Cantacuzino

The House of Cantacuzino (french: Cantacuzène) is a Romanian aristocratic family of Greek origin. The family gave a number of princes to Wallachia and Moldavia, and it claimed descent from a branch of the Byzantine Kantakouzenos family, specifica ...

boyar, was not allowed to marry his French mistress and go free, which had led him to murder his lover and kill himself. The owners would receive a compensation of 8 ''galbeni'' for '' lingurari'' and '' vătraşi'' and 4 ''galbeni'' for '' lăieşi'', the money being provided by the taxes paid by previously freed slaves.

In Wallachia, only two months later, in February 1856, a similar law was adopted by the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

, paying a compensation of 10 ''galbeni'' for each slave, in stages over a number of years.Achim (2004), p.110 The freed slaves had to settle to a town or village and stay there for at least two censuses and they would pay their taxes to the compensation fund.

The condition of the Roma after the abolition

The Romanian abolitionists debated on the future of the former slaves both before and after the laws were passed. This issue became interconnected with the "peasantry issue", an important goal of the being eliminating the

The Romanian abolitionists debated on the future of the former slaves both before and after the laws were passed. This issue became interconnected with the "peasantry issue", an important goal of the being eliminating the corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

and turning bondsmen into small landowners.Achim (2010) p.27 The Ursari (nomadic bear handlers) were the most reticent to the idea of settling down because they saw settling down as becoming slaves again on the owner of the land where they settled. The abolitionists themselves saw turning the former slaves into bondsmen as not something desirable, as they were bound to become dependent again. Nevertheless, the dispute ended after the Romanian Principalities adopted a liberal capitalist property legislation, the corvée being eliminated and the land being divided between the former boyars and the peasants.

Many abolitionists supported the assimilation of the Roma in the Romanian nation, Kogălniceanu noting that there were settled Roma slaves who abandoned their customs and language and they could not be told apart from the Romanians. Among the social engineering techniques proposed for assimilation were: the Roma to be scattered across Romanian villages (within the village and not on the fringes), encouraging inter-ethnical marriages, banning the usage of Romany language and compulsory education

Compulsory education refers to a period of education that is required of all people and is imposed by the government. This education may take place at a registered school or at other places.

Compulsory school attendance or compulsory schooling ...

for their children.Achim (2010) p.31-32 After the emancipation, the state institutions initially avoided the usage of the word ''țigan'' (gypsy), when needed (such as in the case of tax privileges), the official term being ''emancipat''.

Despite the good will of many abolitionists, the social integration of the former slaves was carried out only for a part of them, many of the Roma remaining outside the social organization of the Wallachian, Moldavian and later, Romanian society. The social integration

Social integration is the process during which newcomers or minorities are incorporated into the social structure of the host society.

Social integration, together with economic integration and identity integration, are three main dimensions of ...

policies were generally left to be implemented by the local authorities. In some parts of the country, the nomadic Roma were settled in villages under the supervision of the local police, but across the country, Roma nomadism was not eliminated.

Legacy

Support for the abolitionists was reflected inRomanian literature

Romanian literature () is literature written by Romanian authors, although the term may also be used to refer to all literature written in the Romanian language.

History