Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas refers to

Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas refers to

In

In

By 1499, Spanish settlers on

By 1499, Spanish settlers on  Members of the Spanish religious and legal professions were especially vocal in opposing the enslavement of native peoples. The

Members of the Spanish religious and legal professions were especially vocal in opposing the enslavement of native peoples. The  In the

In the

Enslavement of indigenous peoples was practiced in

Enslavement of indigenous peoples was practiced in

During the 17th and 18th centuries,

During the 17th and 18th centuries,

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico enacted the

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico enacted the

''Hans Staden Among the Tupinambas''

* Carocci, Max

''Written Out of History: Contemporary Native American Narratives of Enslavement''

(2009) * Gallay, Alan

''Forgotten Story of Indian Slavery''

(2003).

"English Trade in Deerskins and Indian Slaves"

''

Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas refers to

Slavery among the indigenous peoples of the Americas refers to slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

of and by the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

. The history of slavery

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of en ...

spans all regions of the world; during the Pre-Columbian era

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the Migration to the New World, original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization of the Americas, European colonization, w ...

, many societies in the Americas enslaved prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

or instituted systems of forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. Contact with Europeans transformed these practices, as the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

introduced chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

through warfare and the cooption of existing systems. Other European powers followed suit, and from the 15th through the 19th centuries, between two and five million indigenous people were enslaved, which had a devastating impact on many indigenous societies, contributing to the overwhelming population decline

A population decline (also sometimes called underpopulation, depopulation, or population collapse) in humans is a reduction in a human population size. Over the long term, stretching from prehistory to the present, Earth's total human population ...

of indigenous peoples in the Americas.

After the decolonization of the Americas

The decolonization of the Americas occurred over several centuries as most of the countries in the Americas gained their independence from European rule. The American Revolution was the first in the Americas, and the British defeat in the Ameri ...

, the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued into the 19th century in frontier regions of some countries, notably parts of Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Northern Mexico

Northern Mexico ( es, el Norte de México ), commonly referred as , is an informal term for the northern cultural and geographical area in Mexico. Depending on the source, it contains some or all of the states of Baja California, Baja California ...

, and the Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado, Ne ...

. Some indigenous groups adopted European-style chattel slavery during the colonial period, most notably the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

" in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, however far more indigenous groups were involved in the selling of indigenous slaves to Europeans.

Pre-Columbian era

Slavery and related practices of forced labor varied greatly between regions and over time. In

In Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

, the most common forms of slavery were those of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

and debtors

A debtor or debitor is a legal entity (legal person) that owes a debt to another entity. The entity may be an individual, a firm, a government, a company or other legal person. The counterparty is called a creditor. When the counterpart of this ...

. People unable to pay back debts could be sentenced to work as slaves to the persons owed until the debts were worked off. The Mayan

Mayan most commonly refers to:

* Maya peoples, various indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Maya civilization, pre-Columbian culture of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Mayan languages, language family spoken ...

and Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

civilizations both practiced slavery. Warfare was important to Maya society

Maya society concerns the social organization of the Pre-Hispanic Maya, its political structures, and social classes. The Maya people were indigenous to Mexico and Central America and the most dominant people groups of Central America up until the ...

, because raids on surrounding areas provided the victims required for human sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

, as well as slaves for the construction of temples. Most victims of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

were prisoners of war or slaves. Slavery was not usually hereditary; children of slaves were born free.

In the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

, workers were subject to a ''Mit'a

Mit'a () was mandatory service in the society of the Inca Empire. Its close relative, the regionally mandatory Minka is still in use in Quechua communities today and known as ''faena'' in Spanish.

Historians use the Hispanicized term ''mita'' to ...

'' in lieu of taxes which they paid by working for the government, a form of corvée labor

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

. Each ''ayllu

The ''ayllu'', a family clan, is the traditional form of a community in the Andes, especially among Quechuas and Aymaras. They are an indigenous local government model across the Andes region of South America, particularly in Bolivia and Peru.

...

'', or extended family, would decide which family member to send to do the work. It is debated whether this system of forced labor counts as slavery.

Many of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are composed of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities. They share certain beliefs, traditions and prac ...

, such as the Haida

Haida may refer to:

Places

* Haida, an old name for Nový Bor

* Haida Gwaii, meaning "Islands of the People", formerly called the Queen Charlotte Islands

* Haida Islands, a different archipelago near Bella Bella, British Columbia

Ships

* , a 1 ...

and Tlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ),

, were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders, raiding as far as California.Ames, Kenneth M.; Maschner, Herbert D. G. (1999). ''Peoples of the northwest coast: their archaeology and prehistory.'' London: Thames & Hudson, p. 196.Green, Jonathan S. (1915). ''Journal of a tour on the north west coast of America in the year 1829, containing a description of a part of Oregon, California and the north west coast and the numbers, manners and customs of the native tribes''. New York city: Reprinted for C. F. Heartman, p. 45.Ames, Kenneth M. (2001). "Slaves, Chiefs and Labour on the Northern Northwest Coast". ''World Archaeology'' 33 (1): 1–17., p. 3. Slavery was hereditary, the slaves being prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. Their targets often included members of the Coast Salish

The Coast Salish is a group of ethnically and linguistically related Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, living in the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. They speak one of the Coas ...

groups. Among some tribes about a quarter of the population were slaves. One slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

was composed by an Englishman, John R. Jewitt

John Rodgers Jewitt (21 May 1783 – 7 January 1821) was an English armourer who entered the historical record with his memoirs about the 28 months he spent as a captive of Maquinna of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people on what is now the Britis ...

, who had been taken alive when his ship was captured in 1802; his memoir provides a detailed look at life as a slave, and asserts that a large number were held.

Other slave-owning societies and tribes of the New World included the Tehuelche of Patagonia, the Kalinago

The Kalinago, also known as the Island Caribs or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated language ...

of Dominica, the Tupinambá of Brazil, and the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska

* ...

of the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

.

European enslavement of indigenous peoples

European enslavement of indigenous Americans began with theSpanish colonization

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

of the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. In Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's letter

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alphabe ...

to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

describing the native Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

, he remarks that "They ought to make good and skilled servants"Robert H. Fuson, ed., ''The Log of Christopher Columbus'', Tab Books, 1992, International Marine Publishing, . and "these people are very simple in war-like matters... I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased". The Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

initially rejected Columbus' enthusiasm for the slave trade. But although they issued a decree in 1500 that specifically forbade the enslavement of indigenous people, they allowed three exceptions which were freely abused by colonial Spanish authorities: slaves taken in "just wars"; those purchased from other indigenous people; or those from groups alleged to practice cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

(such as the Kalinago

The Kalinago, also known as the Island Caribs or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated language ...

).

As other European colonial powers joined the Spanish, the practice of indigenous enslavement was expanded. The new international market

Global marketing is defined as “marketing on a worldwide scale reconciling or taking global operational differences, similarities and opportunities in order to reach global objectives".

Global marketing is also a field of study in general busin ...

for products like tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

, and raw materials incentivized the creation of extraction- and plantation-based economies in eastern North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, such as English Carolina, Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

, and (Lower) French Louisiana. At first, slave labor for these colonies was obtained largely by trading with neighboring tribes, such as the Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

. This trade in slaves was new: prior to the arrival of Europeans, tribes in eastern North America did not view slaves as commodities that could be bought and sold freely. Anthropologist David Graeber

David Rolfe Graeber (; February 12, 1961September 2, 2020) was an American anthropologist and anarchist activist. His influential work in economic anthropology, particularly his books '' Debt: The First 5,000 Years'' (2011) and ''Bullshit Jobs ...

argued that debt and the threat of violence made this sort of transformation of human beings into commodities possible. Tribes like the Yamasee raided for slaves in order to pay back the debt they owed to European traders for finished goods. This in turn created a demand for guns and ammunition, which further indebted the slave-raiding tribes and created a vicious cycle. Most (but not all) tribes in eastern North America had not considered the status of slave heritable, and often integrated the children of slaves into their own communities. The export of slaves to European colonies (and the high death rates there) created an unprecedented population drain. Slave-raiding also led to constant wars between tribes, and eventually destroyed or threatened to destroy most peoples in the vicinity of the colonies. By the mid eighteenth century, population decline, frequent rebellions, and the availability of African slaves had caused a shift away from the large-scale enslavement of indigenous peoples. Although it would be continued on the frontiers, in the economic cores of settler societies indigenous slaves would be replaced with those of African origin.

Spanish colonies

By 1499, Spanish settlers on

By 1499, Spanish settlers on Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

had discovered gold in the Cordillera Central. This created a demand for large amounts of cheap labor, and an estimated 400,000 Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

people from across the island were soon enslaved to work in gold mines. As discussed above, this practice of enslaving native peoples was immediately but ineffectually opposed by the Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

. Succeeding governors

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political_regions, political region, ranking under the Head of State, head of state and in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of ...

were appointed and recalled, often because of stories about their treatment of native populations. The Taíno people also resisted fiercely and were put down in a series of brutal massacres. Nonetheless, forced labor continued and was institutionalized as the ''encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

'' system during the first decade of the 16th century. Under this system, private Spanish colonizers (''encomenderos'') were granted the right to the labor of groups of non-Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

indigenous people. Although based on similar grants given during the ''Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

'' in Spain, in the Caribbean the system quickly became indistinguishable from the slavery it replaced By 1508, the original Taíno population of 400,000 or more had been reduced to around 60,000. Spanish slave-raiding parties travelled across the Caribbean and "carried off entire populations" to work their colonies. Although disease is often pointed to as the cause of this population decline, the first recorded smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

outbreak in the New World was not until 1518. Historian Andrés Reséndez at the University of California, Davis

The University of California, Davis (UC Davis, UCD, or Davis) is a public land-grant research university near Davis, California. Named a Public Ivy, it is the northernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California system. The institut ...

asserts that even though disease was a factor, the indigenous population of Hispaniola would have rebounded the same way Europeans did following the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

if it were not for the constant enslavement they were subject to. He says that "among these human factors, slavery was the major killer" of Hispaniola's population, and that "between 1492 and 1550, a nexus of slavery, overwork and famine killed more natives in the Caribbean than smallpox, influenza or malaria." By 1521, the islands of the northern Caribbean were largely depopulated.

Members of the Spanish religious and legal professions were especially vocal in opposing the enslavement of native peoples. The

Members of the Spanish religious and legal professions were especially vocal in opposing the enslavement of native peoples. The first speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

in the Americas for the universality of human rights and against the abuses of slavery was given on Hispaniola, a mere nineteen years after the first contact. Resistance to indigenous captivity in the Spanish colonies produced the first modern debates over the legitimacy of slavery. Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, author of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

A, or a, is the first Letter (alphabet), letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name ...

, publicized the conditions of indigenous Americans and lobbied Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

to guarantee their rights. The Spanish progressively restricted and outright forbade the enslavement of indigenous Americans in the early years of the Spanish Empire with the Laws of Burgos

The Laws of Burgos ( es, Leyes de Burgos), promulgated on 27 December 1512 in Burgos, Crown of Castile (Spain), was the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spaniards in the Americas, particularly with regard to the Indigenous pe ...

of 1512 and the New Laws

The New Laws (Spanish: ''Leyes Nuevas''), also known as the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians (Spanish: ''Leyes y ordenanzas nuevamente hechas por su Majestad para la gobernación de las Indias y buen t ...

of 1542. The latter replaced the encomienda with the ''repartimiento

The ''Repartimiento'' () (Spanish, "distribution, partition, or division") was a colonial labor system imposed upon the indigenous population of Spanish America. In concept, it was similar to other tribute-labor systems, such as the ''mit'a'' of t ...

'' system, making the indigenous people (in theory) free vassals of the Spanish Crown. Under repartimiento, Amerindians were paid wages for their work, but the work was still obligatory and still carried out under the supervision of a Spanish conquistador. Legally, these labor obligations were not allowed to interfere with the Amerindians' own survival, with only 7-10% of the adult male population allowed to be assigned to work at any time. The implementation of the New Laws and liberation of tens of thousands of indigenous Americans led to a number of rebellions and conspiracies by encomenderos which had to be put down by the Spanish crown. Las Casas' writings gave rise to ''Spanish Black Legend

The Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra) or the Spanish Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra española, link=no) is a theorised historiographical tendency which consists of anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic propaganda. Its proponents argue that its ro ...

'', which Charles Gibson

Charles deWolf Gibson (born March 9, 1943) is an American broadcast television anchor, journalist and podcaster. Gibson was a host of ''Good Morning America'' from 1987 to 1998 and again from 1999 to 2006, and the anchor of ''World News with Char ...

describes as "the accumulated tradition of propaganda and Hispanophobia according to which the Spanish Empire is regarded as cruel, bigoted, degenerate, exploitative and self-righteous in excess of reality". In later centuries, this would be used by other colonial powers to justify their own treatment of native populations as being at least superior to the Spanish alternative.

Despite being technically illegal, indigenous slavery continued in Spanish America for centuries after the promulgation of the New Laws. Even in Spain itself, the use of indigenous slaves did not end until the early 1600s. "Spanish masters resorted to slight changes in terminology, gray areas, and subtle reinterpretations to continue to hold Indians in bondage." Viceroys of New Spain justified enslaving large groups of natives by classifying wars of conquest (such as the Mixtón and Chichimeca War

The Chichimeca War (1550–90) was a military conflict between the Spanish Empire and the Chichimeca Confederation established in the territories today known as the Central Mexican Plateau, called by the Conquistadores La Gran Chichimeca. The ...

s) as rebellions. Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

missions abused their grant of ten years' labor from surrounding peoples as grounds for perpetual servitude. Slavery was a major cause of the Pueblo Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, also known as Popé's Rebellion or Popay's Rebellion, was an uprising of most of the indigenous Pueblo people against the Spanish empire, Spanish colonizers in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, larger than prese ...

of 1680 and other unrest among the indigenous people of northern Mexico. Following the revolt, the business of providing enslaved people for the New Mexico market passed into the hands of the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

, Utes, Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

s, and Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño an ...

s. When the market for slaves began to dry up in the early 18th century, the surplus and ex-slaves settled in New Mexico, forming communities of so-called Genízaros. In 1672, Mariana of Austria

Mariana of Austria ( es, Mariana de Austria) or Maria Anna (24 December 163416 May 1696) was List of Spanish royal consorts, Queen of Spain as the second wife of her uncle Philip IV of Spain from their marriage in 1649 until Philip died in 1665. ...

freed the enslaved indigenous people of Mexico. On 12 June 1679, Charles II issued a general declaration freeing all indigenous slaves in Spanish America. In 1680 this was included in the ''Recopilación de las leyes de Indias'', a codification of the laws of Spanish America. The Kalinago, "cannibals," were the only exception. The royal anti-slavery crusade did not end the enslavement of indigenous people in Spain's American possessions, but, in addition to resulting in the freeing of thousands of enslaved people, it ended the involvement and facilitation by government officials of enslaving by the Spanish; purchase of slaves remained possible but only from indigenous enslavers such as the Kalina

Kalina may refer to:

People

* Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of the northern coastal areas of South America

* Kalina language, or Carib, the language of the Kalina people

* Kalina (given name)

* Kalina (surname)

* Noah Kalina, ...

or the Comanches.

In the

In the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

, the repartimiento system was particularly harsh. The colonial government repurposed the Inca

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

mit'a

Mit'a () was mandatory service in the society of the Inca Empire. Its close relative, the regionally mandatory Minka is still in use in Quechua communities today and known as ''faena'' in Spanish.

Historians use the Hispanicized term ''mita'' to ...

system under their own administration. For over two centuries, thirteen thousand ''mitayos'' were forcefully conscripted every year to work in the silver mines of Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

, Caylloma, and Huancavelica

Huancavelica () or Wankawillka in Quechua is a city in Peru. It is the capital of the department of Huancavelica and according to the 2017 census had a population of 49,570 people. The city was established on August 5, 1572 by the Viceroy ...

. Mitayos were forced to carry backbreaking loads in extreme conditions from the depths of the mine up to the surface.Bakewell, 130. Falls, accidents, and illnesses (including mercury poisoning from the refinement process) were all commonplace. To avoid the repartimiento, thousands fled their traditional villages and forfeited their ''ayllu

The ''ayllu'', a family clan, is the traditional form of a community in the Andes, especially among Quechuas and Aymaras. They are an indigenous local government model across the Andes region of South America, particularly in Bolivia and Peru.

...

'' land rights. From the 16th to late 17th centuries, Upper Peru

Upper Peru (; ) is a name for the land that was governed by the Real Audiencia of Charcas. The name originated in Buenos Aires towards the end of the 18th century after the Audiencia of Charcas was transferred from the Viceroyalty of Peru to th ...

lost nearly 50% of its indigenous population. This only increased the burden on the remaining natives, and by the 1600s, up to half of the eligible male population (as opposed to the repartimiento's original 7-10%) might find themselves working at Potosí in any given year. Laborers were paid, but the pay was dismal: just the cost of traveling to Potosí and back could be more than a mitayo was paid in a year, and so many of them chose to remain in Potosí as wage workers when their service was finished.Bakewell, 125.

In Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Spanish occupation of the lands of the Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

was vigorously contested for 3 centuries in the Arauco War

The Arauco War was a long-running conflict between colonial Spaniards and the Mapuche people, mostly fought in the Araucanía. The conflict began at first as a reaction to the Spanish conquerors attempting to establish cities and force Mapuche ...

. In 1608, shortly after the war began, Philip III formally lifted the prohibition on indigenous slavery for Mapuches caught in war, legalizing what had already become common practice. Legalization made Spanish slave raiding

Slave raiding is a military raid for the purpose of capturing people and bringing them from the raid area to serve as slaves. Once seen as a normal part of warfare, it is nowadays widely considered a crime. Slave raiding has occurred since ant ...

increasingly common, and Mapuche slaves were exported north to places such as La Serena and Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

in Peru. These raids were an underlying cause of the large Mapuche uprising of 1655

The Mapuche uprising of 1655 ( es, alzamiento mapuche de 1655 or ) was a series of coordinated Mapuche attacks against Spanish settlements and forts in colonial Chile. It was the worst military crisis in Chile in decades, and contemporaries even ...

. The uprising continued for an entire decade, and led Philip III's successor Philip IV to change course. Although he died without freeing the slaves outright, his successors would continue his policy towards abolition. Mariana of Austria

Mariana of Austria ( es, Mariana de Austria) or Maria Anna (24 December 163416 May 1696) was List of Spanish royal consorts, Queen of Spain as the second wife of her uncle Philip IV of Spain from their marriage in 1649 until Philip died in 1665. ...

, serving as regent, freed all the indigenous slaves in Peru who had been captured in Chile. After receiving a plea from the Pope, she also freed the slaves of the southern Andes. On 12 June 1679, Charles II issued a general declaration freeing all indigenous slaves in Spanish America. But despite these royal decrees, little changed in reality. There was strong resistance from local elites, such as Governor Juan Enríquez who simply refused to publish Charles II's decrees.

French colonies

Enslavement of indigenous peoples was practiced in

Enslavement of indigenous peoples was practiced in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

from the 17th century. It played a less important role than in Spanish or British colonies because the economy centered on the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

with Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

- and Algonquian-speaking peoples. But the metal weapons these groups acquired from trade were used to devastating effect against the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska

* ...

and Meskwaki

The Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquaki), also known by the European exonyms Fox Indians or the Fox, are a Native American people. They have been closely linked to the Sauk people of the same language family. In the Meskwaki language, the ...

further to the west, and captured slaves were sometimes gifted or traded back to the French. The name '' Panismahas'', a subtribe of the Pawnee, likely became corrupted into a generic term for any slaves of indigenous origin in New France: ''Panis

This is a list of ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes that are mentioned in the literature of Indic religions.

From the second or first millennium BCE, ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes turned into most of the population in the northern p ...

''. Enslavement of panis was formalized through colonial law in 1709, with the passage of the ''Ordinance Rendered on the Subject of the Negroes and the Indians called Panis''. Indigenous slaves could only be kept in bondage while they stayed within the colony, but in practice enslaved individuals remained enslaved regardless of where they travelled. In 1747, the colonial administration proposed permitting the trade of First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

slaves for slaves of African descent. However, these attempts were quashed by the French government, who feared it would jeopardize their strong relations with native tribes. In Lower Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and especially the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (french: Antilles françaises, ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy fwansez) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, ...

, planters generally preferred using African slaves, though in Louisiana some held panis as household servants. Thus Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (, , ; 12 November 1729 – August 1811) was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he took part in the Seven Years' War in North America and the American Revolution ...

concluded in 1757 that the ''Panis'' played "the same role in America that the Negroes do in Europe."

The importation of panis began to decline in the decade prior to the 1760 Conquest of New France

Conquest is the act of military wiktionary:subjugation, subjugation of an enemy by force of Weapon, arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast area ...

. While the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal

The Articles of Capitulation of Montreal were agreed upon between the Governor General of New France, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, and Major-General Jeffery Amherst on behalf of the French and British crowns. They ...

allowed the enslavement of First Nations people to continue, by the late-18th century it had largely been eclipsed by the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. Historian Marcel Trudel

Marcel Trudel (May 29, 1917 – January 11, 2011) was a Canadian historian, university professor (1947–1982) and author who published more than 40 books on the history of New France. He brought academic rigour to an area that had been ma ...

has discovered 4,092 recorded enslaved people throughout Canadian history, of which 2,692 were indigenous, enslaved mostly by French colonists, and 1,400 Black people enslaved mostly by British colonists; collectively, the 4,092 slaves were enslaved by roughly 1,800 enslavers.Cooper, Afua. ''The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montreal'', (Toronto:HarperPerennial, 2006) Trudel also noted 31 marriages took place between French colonists and aboriginal slaves.

British colonies

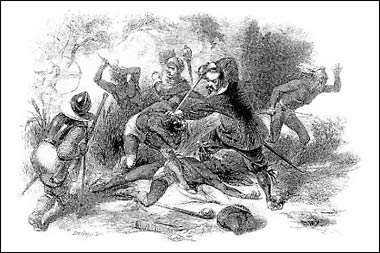

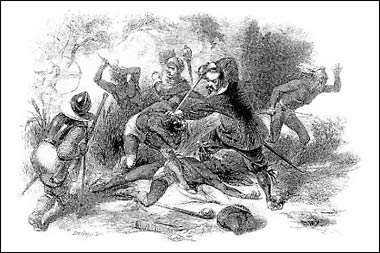

During the 17th and 18th centuries,

During the 17th and 18th centuries, English colonists

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the American Revolutionary War, ...

in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

frequently exported Native slaves to other mainland possessions as well as the "sugar islands" of the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. The source of slaves was mainly prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

, including women and children. The 1677 work '' The Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians'' documents how imprisoned Praying Indians

Praying Indian is a 17th-century term referring to Native Americans of New England, New York, Ontario, and Quebec who converted to Christianity either voluntarily or involuntarily. Many groups are referred to by the term, but it is more commonly ...

, who were allied to the colonists, were also enslaved and sent to Caribbean destinations.

The enslavement and trafficking of indigenous American people was also practiced in the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

, where historian Alan Gallay

Alan Gallay is an American historian. He specializes in the Atlantic World and Early American history, including issues of slavery. He won the Bancroft Prize in 2003 for his ''The Indian Slave Trade: the Rise of the English Empire in the American S ...

notes that during this period more slaves were exported from than imported to the major port of Charles Town. What set Carolina apart from the other English colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America was a substantial population of potential slaves in its hinterlands. The superiority of English trade goods over that of the competing French and Spanish also played an important role in centralizing trade in Carolina. Sometimes the colonists captured the slaves themselves, but more often bought them from native tribes who came to specialize in slave raids. One of the first of these was the Westo

The Westo were an Iroquoian Native American tribe encountered in the Southeastern U.S. by Europeans in the 17th century. They probably spoke an Iroquoian language. The Spanish called these people Chichimeco (not to be confused with Chichimeca i ...

, followed by many others including the Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, and Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlandsrum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Ph ...

, European jewelry, needles, and scissors, varied among the tribes, but the most prized were rifles. The depletion of indigenous populations coupled with revolts (such as the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

) would eventually lead to Native Americans being replaced with African slaves in the colonial southeast.Brown, Philip M. 1975. "Early Indian Trade in the Development of South Carolina: Politics, Economics, and Social Mobility during the Proprietary Period, 1670–1719." The South Carolina Historical Magazine 76 (3): 118–28.

The exact number of Native Americans who were enslaved is unknown because vital statistics and census reports were at best infrequent. Historian Alan Gallay estimates that from 1670 to 1715, English slave traders in Carolina sold between 24,000 and 51,000 Native Americans from what is now the southern part of the U.S. Andrés Reséndez estimates that between 147,000 and 340,000 Native Americans were enslaved in North America, excluding Mexico. Even after the Indian Slave Trade ended in 1750 the enslavement of Native Americans continued in the west, and also in the Southern states mostly through kidnappings.

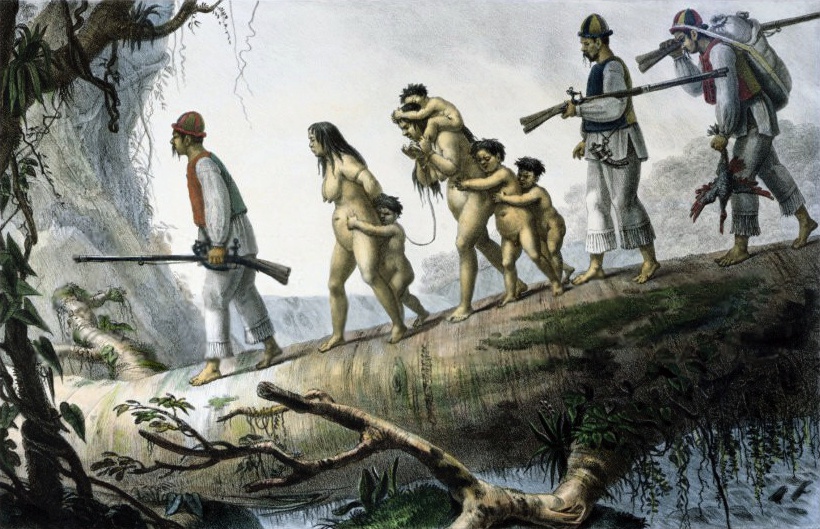

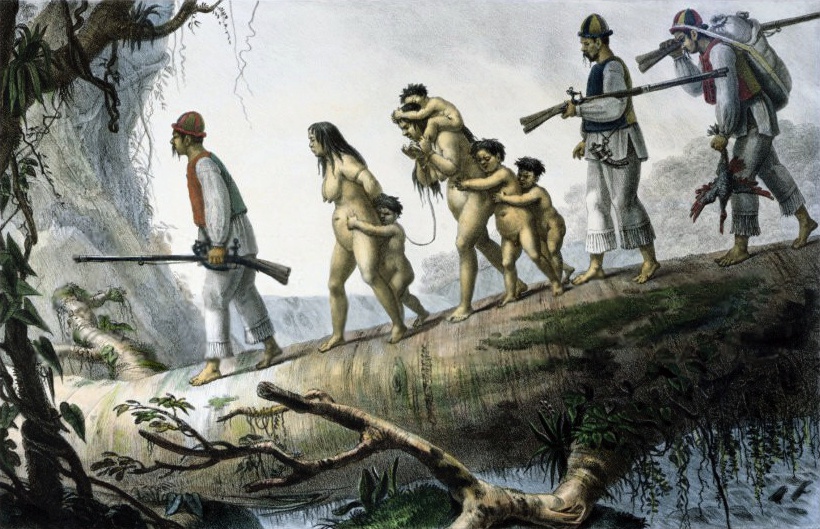

Portuguese Brazil

In Brazil, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor during the initial phases of settlement to maintain thesubsistence economy

A subsistence economy is an economy directed to basic subsistence (the provision of food, clothing, shelter) rather than to the market. Henceforth, "subsistence" is understood as supporting oneself at a minimum level. Often, the subsistence econo ...

, and natives were often captured by expeditions called ''bandeiras'' ("Flags", from the flag of Portugal they carried in a symbolic claiming of new lands for the country). Bandeirantes frequently targeted Jesuit reduction

Reductions ( es, reducciones, also called ; , pl. ) were settlements created by Spanish rulers and Roman Catholic missionaries in Spanish America and the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America, such red ...

s, capturing thousands of natives from them in the early 1600s. In 1629, Antônio Raposo Tavares

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular ma ...

led a bandeira, composed of 2,000 allied índios, "Indians", 900 mamelucos, "mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

s" and 69 whites, to find precious metals and stones and to capture Indians for slavery. This expedition alone was responsible for the enslavement of over 60,000 indigenous people. Conflict between settlers who wanted to enslave Indians and Jesuits who sought to protect them was common throughout the era, particularly as disease reduced the Indian populations. In 1661, for example, Padre António Vieira's attempts to protect native populations lead to an uprising and the temporary expulsion of the Jesuits in Maranhão

Maranhão () is a state in Brazil. Located in the country's Northeast Region, it has a population of about 7 million and an area of . Clockwise from north, it borders on the Atlantic Ocean for 2,243 km and the states of Piauí, Tocantins and ...

and Pará

Pará is a Federative units of Brazil, state of Brazil, located in northern Brazil and traversed by the lower Amazon River. It borders the Brazilian states of Amapá, Maranhão, Tocantins (state), Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas (Brazilian state) ...

. The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 19th century.

Indigenous slavery after colonial independence

United States

After the mid-1700s, it becomes more difficult to track the history of Native American enslavement in what became theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

outside the territories that would be acquired after the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexicans, Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% ...

. Indian slavery had declined on a large scale, and as a result, those Native Americans who were still enslaved were either not recorded or they were not differentiated from African slaves. For example, in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

Sarah Chauqum was listed her as a mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

, but she won her freedom by proving her Narragansett identity. That said, records and slave narratives archived by the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

(WPA) clearly indicate that the enslavement of Native Americans continued in the 1800s, mostly through kidnappings. One example is a WPA interview with a former slave, Dennis Grant, whose mother was full-blooded Native American. She was kidnapped as a child near Beaumont, Texas

Beaumont is a coastal city in the U.S. state of Texas. It is the county seat, seat of government of Jefferson County, Texas, Jefferson County, within the Beaumont–Port Arthur, Texas, Port Arthur Beaumont–Port Arthur metropolitan area, metropo ...

in the 1850s, made a slave, and later forced to become the wife of another enslaved person.

Southwestern states

TheMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

brought large swathes of territory into the United States where Native American slavery was practiced at scale, and the states and territories created to govern these lands often legalized or expanded the practice. The Indian Act of 1850 sanctioned the enslavement of Native Americans in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

under the guise of stopping vagrancy. The act "facilitated removing California Indians from their traditional lands, separating at least a generation of children and adults from their families, languages, and cultures...and indenturing Indian children and adults to Whites." Due to the nature of California court records, it is difficult to estimate of the number of Native Americans enslaved as a result of the legislation. Benjamin Madley places the number at somewhere between 24,000 and 27,000, including 4,000 to 7,000 children. During the period the legislation was in effect, the Native Californian population of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

decreased from 3,693 to 219 people. Although the California legislature repealed parts of the statute after the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representativ ...

abolished involuntary servitude in 1865, it was not repealed in its entirety until 1937.

Both debt peonage

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the per ...

and Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

slaveholding were well established in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

when it became a territory. Native American slaves were in the households of many prominent New Mexicans, including the governor and Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and n ...

. Black slaves, in contrast, were vanishingly rare. The Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

allowed New Mexico to choose its own stance on slavery, and in 1859, it was formally legalized. This move was not without opposition: soon after the treaty had been signed, a group of prominent New Mexicans petitioned Congress to prevent slavery from being made legal. They were likely motivated by their desire for self-government and a fear of invasion by the slave state of Texas. On June 19, 1862, Congress prohibited slavery in all US territories. Prominent New Mexicans petitioned the Senate for compensation for the 600 Indian slaves that were going to be set free. The Senate denied their request and sent federal agents to abolish slavery. But the years from 1864 to 1866 saw an expansion rather than a decline of Native American enslavement in New Mexico. This was a consequence of the Long Walk of the Navajo

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo ( nv, Hwéeldi), was the 1864 deportation and attempted ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government. Navajos were forced to walk from t ...

, during which the federal government organized some 53 separate death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convent ...

es of Navajo from their land in what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. Taking advantage of their vulnerable position, Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

and Ute

Ute or UTE may refer to:

* Ute (band), an Australian jazz group

* Ute (given name)

* ''Ute'' (sponge), a sponge genus

* Ute (vehicle), an Australian and New Zealand term for certain utility vehicles

* Ute, Iowa, a city in Monona County along ...

enslavers captured many Navajo and sold them as slaves in places as far away as Conejos County, Colorado

Conejos County is a county located in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 census, the population was 7,461. The county seat is the unincorporated community of Conejos.

Being 50.7% Hispanic in 2020, Conejos was Colorado's largest Hispa ...

. Thus, when Special Indian Agent J.K. Graves visited in June 1866, he found that slavery was still widespread, and many of the federal agents had slaves. In his report, he estimated that there were 400 slaves in Santa Fe alone. On March 2, 1867, Congress passed the Peonage Act of 1867

The Peonage Abolition Act of 1867 was an Act passed by the U.S. Congress on March 2, 1867, that abolished peonage in the New Mexico Territory and elsewhere in the United States.

Designed to help enforce the Thirteenth Amendment, the Act declare ...

, which specifically targeted New Mexican slavery. After this act, the number of slaves taken dropped sharply in the 1870s.

Utah

Shortly after theMormon pioneers

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also known as Latter Day Saints, who migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the Midwest to the S ...

settled Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

on the lands of the Western Shoshone Western Shoshone comprise several Shoshone tribes that are indigenous to the Great Basin and have lands identified in the Treaty of Ruby Valley 1863. They resided in Idaho, Nevada, California, and Utah. The tribes are very closely related cultural ...

, Weber Ute

Ute or UTE may refer to:

* Ute (band), an Australian jazz group

* Ute (given name)

* ''Ute'' (sponge), a sponge genus

* Ute (vehicle), an Australian and New Zealand term for certain utility vehicles

* Ute, Iowa, a city in Monona County along ...

, and Southern Paiute

The Southern Paiute people are a tribe of Native Americans who have lived in the Colorado River basin of southern Nevada, northern Arizona, and southern Utah. Bands of Southern Paiute live in scattered locations throughout this territory and ha ...

, conflict with nearby Native American groups began. At the Battle at Fort Utah

The Battle at Fort Utah (also known as Fort Utah War or Provo War) was a battle between the Timpanogos Tribe and remnants of the Nauvoo Legion at Fort Utah in modern-day Provo, Utah. The Timpanogos people initially tolerated the presence of the ...

, Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

led the enslavement of many Timpanogo women and children. In the winter of 1849–1850, after expanding into Parowan

Parowan ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Iron County, Utah, United States. The population was 2,790 at the 2010 census, and in 2018 the estimated population was 3,100.

Parowan became the first incorporated city in Iron County in 1851. A ...

, Mormons attacked a group of Indians, killing around 25 men and taking the women and children as slaves. News of the enslavement reached the US Government, who appointed Edward Cooper as Indian Agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

to combat enslavement in September 1850. But at the encouragement of Mormon leaders, the Mormon participation in the Indian slave trade continued to expand. In 1851, Apostle George A. Smith gave Chief Peteetneet

Chief Peteetneet, or more precisely ''Pah-ti't-ni't'' (pronounced Paw-tee't-nee't), was a clan leader of a band of Timpanogos that lived near Peteetneet Creek, which was named for him (or perhaps for which he was named), in what is now known as ...

and Walkara

Chief Walkara (c. 1808 – 1855; also known as Wakara, Wahkara, Chief Walker or Colorow) was a Shoshone leader of the Utah Indians known as the Timpanogo and Sanpete Band. It is not completely clear what cultural group the Utah or Timp ...

talking papers that certified "it is my desire that they should be treated as friends, and as they wish to Trade horses, Buckskins

Buckskins are clothing, usually consisting of a jacket and leggings, made from buckskin, a soft sueded leather from the hide of deer. Buckskins are often trimmed with a fringe – originally a functional detail, to allow the garment to s ...

and Piede children, we hope them success and prosperity and good bargains." In May 1851 Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

met with settlers in the Parawon region and encouraged them to "buy up the Lamanite

The Lamanites () are one of the four ancient peoples (along with the Jaredites, the Mulekites, and the Nephites) described as having settled in the ancient Americas in the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the Latter Day Saint movement. The Lamani ...

children as fast as they could".

However, the Mormons strongly opposed the New Mexican slave trade, which caused sometimes dramatic conflicts with the slave traders. When Don Pedro León Luján was caught violating the Nonintercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

in November 1851 by attempting to trade slaves with the Indians without a valid license, he and his party were prosecuted. His property was seized and the child slaves were sold to Mormon families in Manti. In another incident, Ute Chief Arrapine demanded that the Mormons purchase a group of children that they had prevented him from selling to the Mexicans. When they refused, he executed the captives.

In March 1852, the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state. ...

formally legalized Indian slavery with the Act for the relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners. Mormons continued taking children from their families long after the slave traders left and even began to actively solicit children from parents. They also began selling Indian slaves to each other. By 1853, each of the hundred households in Parowan had one or more Southern Paiute

The Southern Paiute people are a tribe of Native Americans who have lived in the Colorado River basin of southern Nevada, northern Arizona, and southern Utah. Bands of Southern Paiute live in scattered locations throughout this territory and ha ...

children kept as slaves. Indian slaves were used for both domestic

Domestic may refer to:

In the home

* Anything relating to the human home or family

** A domestic animal, one that has undergone domestication

** A domestic appliance, or home appliance

** A domestic partnership

** Domestic science, sometimes c ...

and manual labor

Manual labour (in Commonwealth English, manual labor in American English) or manual work is physical work done by humans, in contrast to labour by machines and working animals. It is most literally work done with the hands (the word ''manual'' ...

. The practice of Indian enslavement concerned the Republican Party, who had made anti-slavery one of the pillars of their platform. While considering appropriations for the Utah Territory, Representative Justin Smith Morrill

Justin Smith Morrill (April 14, 1810December 28, 1898) was an American politician and entrepreneur who represented Vermont in the United States House of Representatives (1855–1867) and United States Senate (1867–1898). He is most widely remem ...

criticized its laws on Indian slavery. He said that the laws were unconcerned about the way the Indian slaves were captured, noting that the only requirement was that the Indian be possessed by a white person through purchase or otherwise. He said that Utah was the only American government to enslave Indians, and said that state-sanctioned slavery "is a dreg placed at the bottom of the cup by Utah alone". He estimated that in 1857 there were 400 Indian slaves in Utah, but historian Richard Kitchen estimates far more went unrecorded because of their high mortality rate: over half died by their early 20s. Those who survived and were released generally found themselves without a community, full members of neither their original tribes nor the white communities in which they were raised. The Republicans' abhorrence of slavery in Utah delayed Utah's entrance as a state into the Union.

Mexico

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico enacted the

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico enacted the Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guaran ...

, which decreed that indigenous tribes within its borders were citizens of Mexico. Officially, the newly independent Mexican government proclaimed a policy of social equality for all ethnic groups, and the genízaros were officially considered equals to their ''vecino

'Vecino' means either "neighbour" or resident in modern Spanish. Historically in the Spanish Empire it referred instead to a householder of considerable social position in a town or a city, and was similar to "freeman" or "freeholder."

Histori ...

'' (villagers of mainly mixed racial background) and Pueblo neighbors. Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

abolished slavery in 1829. But this never was completely put into practice. The Mexican slave trade continued to flourish, because the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, co ...

had disrupted the defenses at the border. For decades the region was subject to raids by Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño an ...

s, Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and eve ...

s, and large Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

war parties who looted, killed and took slaves. The average price for a boy slave was $100, while girls brought $150 to $200. Girls demanded a higher price because they were thought to be excellent house keepers and they were frequently used as sex slaves. Bent's Fort

Bent's Old Fort is an 1833 fort located in Otero County in southeastern Colorado, United States. A company owned by Charles Bent and William Bent and Ceran St. Vrain built the fort to trade with Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Plains Indians and ...

, a trading post on the Santa Fe Trail, was one customer of the enslavers, as were Comanchero

The Comancheros were a group of 18th- and 19th-century traders based in northern and central New Mexico. They made their living by trading with the nomadic Great Plains Indian tribes in northeastern New Mexico, West Texas, and other parts of the ...

s, Hispanic traders based in New Mexico. Some border communities in Mexico itself were also in the market for slaves. But in general, Mexican landowners and magnates turned to debt peonage

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the per ...

, advancing money to workers on terms that were impossible to meet. Laws were passed requiring servants to complete the terms of any contract for service, essentially reinstating slavery in a new form.

The Mexican secularization act of 1833

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

"freed" the indigenous people attached to the missions of California, providing for distribution of land to mission indigenous people and sale of remaining grazing land. But through grants and auctions, the bulk of the land was transferred to wealthy ''Californios

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californians, Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish language, Spanish-s ...

'' and other investors. Any indigenous people who had received land soon fell into debt peonage and became attached to the new Ranchos. The workforce was supplemented with indigenous people who had been captured.

Indigenous involvement in colonial and postcolonial slavery

Indigenous peoples participated in the colonial era slave trade in several ways. During the period of widespread enslavement of indigenous peoples, tribes such as theWesto

The Westo were an Iroquoian Native American tribe encountered in the Southeastern U.S. by Europeans in the 17th century. They probably spoke an Iroquoian language. The Spanish called these people Chichimeco (not to be confused with Chichimeca i ...

, Yamasee