Sir William Joynson-Hicks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

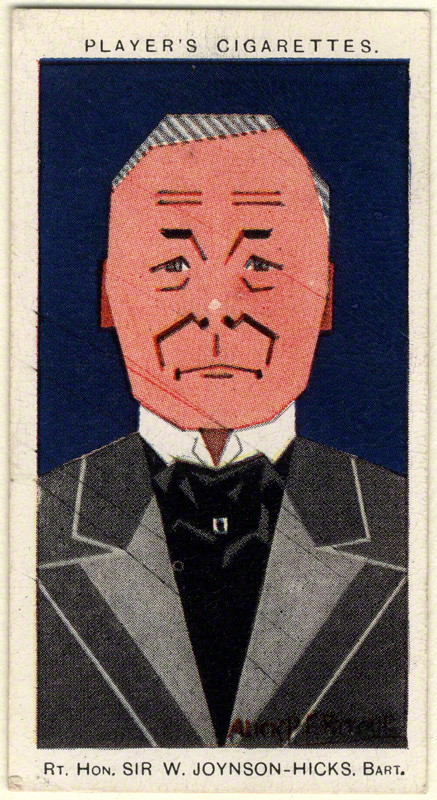

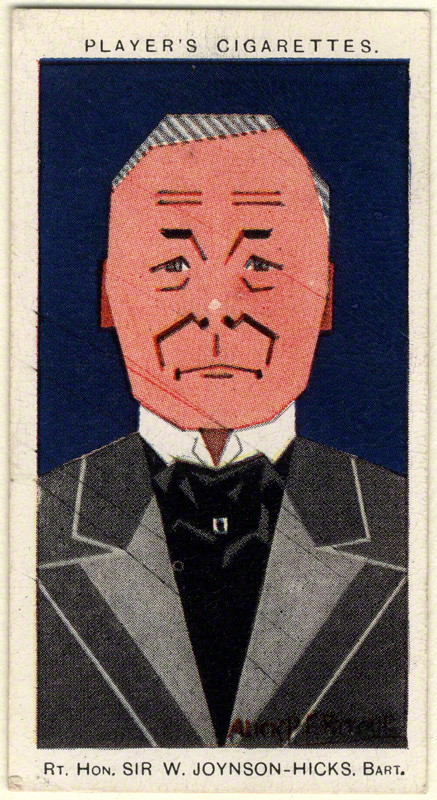

William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford, (23 June 1865 – 8 June 1932), known as Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Bt, from 1919 to 1929 and popularly known as Jix, was an

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

solicitor and Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

politician.

He first attracted attention in 1908 when he defeated Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, a Liberal Cabinet Minister at the time, in a by-election for the seat of North-West Manchester but is best known as a long-serving and controversial Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

in Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

's Second Government from 1924 to 1929. He gained a reputation for strict authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political '' status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

, opposing Communism and clamping down on nightclubs and what he saw as indecent literature. He also played an important role in the fight against the introduction of the Church of England Revised Prayer Book, and in lowering the voting age for women from 30 to 21.

Early life and career

Background and early life

William Hicks, as he was initially called, was born in Canonbury, London on 23 June 1865.Matthew 2004, p38 He was the eldest of four sons and two daughters of Henry Hicks, of Plaistow Hall,Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, and his wife Harriett, daughter of William Watts. Hicks was a prosperous merchant and senior evangelical Anglican layman who demanded the very best from his children.

William Hicks was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, London

Small things grow in harmony

, established =

, closed =

, coordinates =

, pushpin_map =

, type = Independent school (UK), Independent day school

, religion ...

(1875–81).Taylor

Taylor, Taylors or Taylor's may refer to:

People

* Taylor (surname)

**List of people with surname Taylor

* Taylor (given name), including Tayla and Taylah

* Taylor sept, a branch of Scottish clan Cameron

* Justice Taylor (disambiguation)

Plac ...

, pp. 29–30 He "took the pledge" (to abstain from alcohol) at the age of 14 and kept it all his life.

Marriage

In 1894 while on holiday, he met Grace Lynn Joynson, daughter of a silk manufacturer. Her father was also a Manchester evangelical Tory. They were married on 12 June 1895. In 1896 he added his wife's name "Joynson" to his surname.Joynson Hicks

After leaving school, Hicks was articled to a Londonsolicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

between 1881 and 1887, before setting up his own practice in 1888. Initially he struggled to attract clients, but he was helped by his father's position as a leading member of the City Common Council and as Deputy Chairman of the London General Omnibus Company

The London General Omnibus Company or LGOC, was the principal bus operator in London between 1855 and 1933. It was also, for a short period between 1909 and 1912, a motor bus manufacturer.

Overview

The London General Omnibus Company was fou ...

, for whom he did a great deal of claims work. His law firm was still operating as late as 1989, when a guide to the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988c 48, also known as the CDPA, is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that received Royal Assent on 15 November 1988. It reformulates almost completely the statutory basis of copyright law ( ...

was published as ''Joynson-Hicks on UK Copyright''.

In 1989, Joynson-Hicks merged with Taylor Garrett to form Taylor Joynson Garrett which itself merged with German law firm Wessing & Berenberg-Gossler to form Taylor Wessing

Taylor Wessing LLP is an international law firm with 28 offices internationally. The firm has over 300 partners and over 1000 lawyers worldwide. The company was formed as a result of a merger of the British law firm ''Taylor Joynson Garrett'' a ...

in 2002.

Early attempts to enter Parliament

He joined the Conservative Party (at that time part of the Unionist coalition, which name it retained until 1925) and was selected as a Conservative Parliamentary candidate in 1898. He unsuccessfully contested seats inManchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

in the general elections of 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

and 1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

, losing to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. On the latter occasion, he made anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

speeches. At the time, there was an influx of Russian Jews fleeing from pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

, which had caused Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

's government to pass the Aliens Act 1905

The Aliens Act 1905 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.Moving Here The Act introduced immigration controls and registration for the first time, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for ma ...

).

Motoring expert

Joynson-Hicks was an early authority on transport law, particularly motoring law. In 1906 he published "The Law of Heavy and Light Mechanical Traction on Highways". He was beginning to acquire a reputation as an evangelical lawyer with a perhaps paradoxical interest in the latest technology: motor cars (of which he owned several), telephones and aircraft. In 1907 he became Chairman of the Motor Union, and presided over the merger withThe Automobile Association

AA Limited, trading as The AA (formerly The Automobile Association), is a British motoring association.

Founded in 1905, it provides vehicle insurance, driving lessons, breakdown cover, loans, motoring advice, road maps and other services. Th ...

in 1911, serving as chairman of the merged body until 1922. One of his first actions was to assert the legality of AA patrols warning motorists of police speed trap

Speed limits are enforced on most public roadways by authorities, with the purpose to improve driver compliance with speed limits. Methods used include roadside speed traps set up and operated by the police and automated roadside 'speed camera' ...

s.

He was also President of the Lancashire Commercial Motor Users’ Association of the National Threshing Machine

A threshing machine or a thresher is a piece of farm equipment that threshes grain, that is, it removes the seeds from the stalks and husks. It does so by beating the plant to make the seeds fall out.

Before such machines were developed, threshi ...

Owners’ Association, and of the National Traction Engine

A traction engine is a steam engine, steam-powered tractor used to move heavy loads on roads, plough ground or to provide power at a chosen location. The name derives from the Latin ''tractus'', meaning 'drawn', since the prime function of any t ...

Association.

He was also Treasurer of the Zenana Bible and Medical Mission The International Service Fellowship, more commonly known as Interserve, is an interdenominational Protestant Christian charity which was founded in London in 1852. For many years it was known as the Zenana Bible and Medical Missionary Society and i ...

and a member of the finance committee of the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

.

1908 by-election

Joynson-Hicks was elected to Parliament in aby-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

in 1908, when Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

was obliged to submit to re-election in Manchester North West after his appointment as President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

, as the Ministers of the Crown Act 1908 required newly appointed Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

ministers to re-contest their seats. Cabinet ministers were normally returned unopposed, but as Churchill had crossed the floor

Crossed may refer to:

* ''Crossed'' (comics), a 2008 comic book series by Garth Ennis

* ''Crossed'' (novel), a 2010 young adult novel by Ally Condie

* "Crossed" (''The Walking Dead''), an episode of the television series ''The Walking Dead''

S ...

from the Conservatives to the Liberals in 1904, the Conservatives were disinclined to allow him an uncontested return.

Ronald Blythe

Ronald George Blythe (born 6 November 1922)"Dr Ronald Blythe ...

in "The Salutary Tale of Jix" in ''The Age of Illusion'' (1963) called it "the most brilliant, entertaining and hilarious electoral fight of the century". Joynson-Hicks' nickname "Jix" dates from this by-election. The election was notable for both the attacks of the Suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

movement on Churchill, over his refusal to support legislation that would give women the vote, and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

ish hostility to Joynson-Hicks over his support for the controversial Aliens Act which aimed to restrict Jewish immigration.Paul Addison

Paul Addison (3 May 1943 – 21 January 2020) was a British historian known for his research on the political history of Britain during the Second World War and the post-war period. Addison was part of the first generation of academic historia ...

, ''Churchill on the Home Front 1900–1955'' (2nd ed., London 1993) p. 64

Joynson-Hicks called Labour leader Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

"a leprous traitor" who wanted to sweep away the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

. This prompted H G Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Joynson-Hicks defeated Churchill. This provoked a strong reaction across the country with ''

The Conservatives returned to power in November 1924 and Joynson-Hicks was appointed as

The Conservatives returned to power in November 1924 and Joynson-Hicks was appointed as

In 1927 Joynson-Hicks turned his fire on the proposed revision of the ''

In 1927 Joynson-Hicks turned his fire on the proposed revision of the ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' running the front-page headline "Winston Churchill is OUT! OUT! OUT!" (Churchill shortly returned to Parliament as MP for Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

).

Joynson-Hicks gained personal notoriety in the immediate aftermath of this election for an address to his Jewish hosts at a dinner given by the Maccabean Society, during which he said "he had beaten them all thoroughly and soundly and was no longer their servant." Subsequent allegations that he was personally anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

formed an important strand of the authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

streak that many, including recent scholars David Cesarani

David Cesarani (13 November 1956 – 25 October 2015) was a British historian who specialised in Jewish history, especially the Holocaust. He also wrote several biographies, including ''Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind'' (1998).

Early life ...

and Geoffrey Alderman

Geoffrey Alderman (born 10 February 1944) is a British historian that specialises in 19th and 20th centuries Jewish community in England. He is also a political adviser and journalist.

Life

Born in Middlesex, Alderman was educated at Hackney D ...

, detected in his speeches and behaviour. Cesarani cautioned that "although he may have been nicknamed "Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

Minor", Jix was no fascist." Other work has disputed the notion that Joynson-Hicks was an anti-Semite, most notably a major article by W. D. Rubinstein which asserted that as Home Secretary Joynson-Hicks would later allow more Jews to be naturalised

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the i ...

than any other holder of that office. Whether or not it was justified, the notion that Joynson-Hicks was an anti-Semite played a large part in his portrayal as a narrow-minded and intolerant man, most obviously in the work of Ronald Blythe.

Early Parliamentary career

Joynson-Hicks lost his seat in theJanuary 1910 general election

The January 1910 United Kingdom general election was held from 15 January to 10 February 1910. The government called the election in the midst of a constitutional crisis caused by the rejection of the People's Budget by the Conservative-dominat ...

. He contested Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

in the second general election in December that year, but was again defeated. He was returned unopposed for Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings whi ...

at a by-election in March 1911.

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he formed a Pals battalion

The Pals battalions of World War I were specially constituted battalions of the British Army comprising men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside their friends, neighbour ...

within the Middlesex Regiment

The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1966. The regiment was formed, as the Duke of Cambridge's Own (Middlesex Regiment), in 1881 as part of the Childers Re ...

, the "Football Battalion

The 17th (Service) Battalion, Middlesex Regiment was an infantry battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, part of the British Army, which was formed as a Pals battalion during the Great War. The core of the battalion was a group of professional footbal ...

." He acquired a reputation as a well-informed backbencher, an expert on aircraft and motors, badgering ministers about matters of aircraft design and production and methods of attacking Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s. On 12 May 1915, he presented a petition to the Commons demanding the internment of enemy aliens of military age and the withdrawal from coastal areas of all enemy aliens. In 1916 he published a pamphlet ''The Command of the Air'' in which he advocated indiscriminate bombing of civilians in German cities, including Berlin. However, he was not offered a government post.Matthew 2004, p39

In 1918

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50–100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

, his old constituency having been abolished, he became MP for Twickenham

Twickenham is a suburban district in London, England. It is situated on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames since 1965, and the boroug ...

, holding the seat until his retirement from the House of Commons in 1929.

For his war work, he was created a Baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

, of Holmbury in the County of Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

, in 1919.

The Lloyd George Coalition

In 1919-20 he went on an extended visit to theSudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, which changed his political fortunes. At the time, there was considerable unrest in India and a rapid growth in the Home Rule movement, something Joynson-Hicks opposed due to the great economic importance of the Indian Empire

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

to Britain. He at one time had commented "I know it is frequently said at missionary meetings that we conquered India to raise the level of the Indians. That is cant. We hold it as the finest outlet for British goods in general, and for Lancashire cotton goods in particular."

He emerged as a strong supporter of General Reginald Dyer

Colonel Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, CB (9 October 1864 – 23 July 1927) was an officer of the Bengal Army and later the newly constituted British Indian Army. His military career began serving briefly in the regular British Army before tra ...

over the Amritsar Massacre

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large peaceful crowd had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, British India, Punjab, to protest against the Rowlatt Act and arre ...

, and nearly forced the resignation of the Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of th ...

, Edwin Montagu

Edwin Samuel Montagu PC (6 February 1879 – 15 November 1924) was a British Liberal politician who served as Secretary of State for India between 1917 and 1922. Montagu was a "radical" Liberal and the third practising Jew (after Sir Herber ...

, over the motion of censure the government put down concerning Dyer's actions. This episode established his reputation as one of the "die-hards" on the right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

of the party, and he emerged as a strong critic of the party's participation in a coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

government with the Liberal David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

.

As part of this campaign, he led an abortive attempt to block Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

's nomination as leader of the Unionist party on Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

's retirement, putting forward Lord Birkenhead

Earl of Birkenhead was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1922 for the noted lawyer and Conservative politician F. E. Smith, 1st Viscount Birkenhead. He was Solicitor-General in 1915, Attorney-General from 1915 to ...

instead with the express aim of "splitting the coalition".

Entering government

Joynson-Hicks played a small role in the fall of the Lloyd George Coalition, which he had so disliked, in October 1922. The refusal of many leading Conservatives, who had been supporters of the Coalition, to serve inBonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

's new government opened up promotion prospects. Joynson-Hicks was appointed Secretary for Overseas Trade

The Secretary for Overseas Trade was a junior Ministerial position in the United Kingdom government from 1917 until 1953, subordinate to the President of the Board of Trade. The office was replaced by the Minister of State for Trade on 3 Septembe ...

(a junior minister, effectively deputy to the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

). In the fifteen-month Conservative administration of first Bonar Law and then Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, Joynson-Hicks was rapidly promoted. In March 1923, he became Paymaster-General

His Majesty's Paymaster General or HM Paymaster General is a ministerial position in the Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom. The incumbent Paymaster General is Jeremy Quin MP.

History

The post was created in 1836 by the merger of the posit ...

then Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

, filling positions left vacant by the promotion of Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

.

When Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

in May 1923, he initially also retained his previous position of Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

while searching for a permanent successor. To relieve the burden of this position, he promoted Joynson-Hicks to Financial Secretary to the Treasury

The financial secretary to the Treasury is a mid-level ministerial post in HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. It is nominally the fifth most significant ministerial role within the Treasury after the First Lord of the Treasury, first lord of th ...

and included him in the Cabinet.

In that role, Joynson-Hicks was responsible for making the ''Hansard

''Hansard'' is the traditional name of the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official print ...

'' statement, on 19 July 1923, that the Inland Revenue

The Inland Revenue was, until April 2005, a department of the British Government responsible for the collection of direct taxation, including income tax, national insurance contributions, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, corporation ta ...

would not prosecute a defaulting taxpayer who made a full confession and paid the outstanding tax, interest and penalties. Joynson-Hicks had hopes of eventually becoming Chancellor himself, but instead Neville Chamberlain was appointed to the post in August 1923. Once more, Joynson-Hicks filled the gap left by Chamberlain's promotion, serving as Minister of Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Coun ...

. He became a Privy Counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a privy council, formal body of advisers to the British monarchy, sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises Politics of the United King ...

in 1923.

Following the hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

, amounting to a Unionist defeat in the general election of December 1923, Joynson-Hicks became a key figure in various intra-party attempts to oust Baldwin. At one time, the possibility of his becoming leader himself was discussed, but it seems to have been quickly discarded. He was involved in a plot to persuade Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

that should the King seek his advice on whom to appoint Prime Minister, Balfour would advise him to appoint Austen Chamberlain or Lord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869, known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley) was a British statesman, three-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

Prime Minister instead of Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

. The plot failed when Balfour refused to countenance such a move and the Liberals publicly announced they would support MacDonald, causing the government to fall in January 1924. MacDonald then became the first Labour Prime Minister.

Home Secretary

The Conservatives returned to power in November 1924 and Joynson-Hicks was appointed as

The Conservatives returned to power in November 1924 and Joynson-Hicks was appointed as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

. Francis Thompson

Francis Joseph Thompson (16 December 1859 – 13 November 1907) was an English poet and Catholic mystic. At the behest of his father, a doctor, he entered medical school at the age of 18, but at 26 left home to pursue his talent as a writer a ...

described him as "the most prudish, puritanical and protestant Home Secretary of the twentieth century". Promotion appears to have gone to his head somewhat and he allowed himself to be touted as a prospective party leader, a possibility which Leo Amery

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery, (22 November 1873 – 16 September 1955), also known as L. S. Amery, was a British Conservative Party politician and journalist. During his career, he was known for his interest in military preparedness, ...

dismissed as "amazing" (October 1925). In his role as Home Secretary he was in attendance at the birth of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

in April 1926.

Public morals

Joynson-Hicks was portrayed as a reactionary for his attempts to crack down onnight club

A nightclub (music club, discothèque, disco club, or simply club) is an entertainment venue during nighttime comprising a dance floor, lightshow, and a stage for live music or a disc jockey (DJ) who plays recorded music.

Nightclubs gener ...

s and other aspects of the "Roaring Twenties

The Roaring Twenties, sometimes stylized as Roaring '20s, refers to the 1920s decade in music and fashion, as it happened in Western society and Western culture. It was a period of economic prosperity with a distinctive cultural edge in the U ...

". He was also heavily implicated in the banning of Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel ''The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name Jo ...

's lesbian novel, ''The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (homo ...

'' (1928), in which he took a personal interest.

He wanted to stem what he called "the flood of filth coming across the Channel". He clamped down on the work of D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

(he helped to force the publication of ''Lady Chatterley's Lover

''Lady Chatterley's Lover'' is the last novel by English author D. H. Lawrence, which was first published privately in 1928, in Italy, and in 1929, in France. An unexpurgated edition was not published openly in the United Kingdom until 1960, w ...

'' in an expurgated version), as well as on books on birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

and the translation of ''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label=Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Dan ...

''. He ordered the raiding of nightclubs, where a great deal of after-hours drinking took place, with many members of fashionable society being arrested. The nightclub owner Kate Meyrick

Kate Meyrick (7 August 1875 – 19 January 1933) known as the 'Night Club Queen' was an Irish night-club owner in 1920s London. During her 13 year career she made, and spent, a fortune and served five prison sentences. She was the inspiration fo ...

, proprietor of The 43 Club amongst other venues, was in and out of prison five times, her release parties being causes for big champagne celebrations. He instructed the head of London’s Metropolitan Police, William Horwood that ‘it is a place of the most intense mischief and immorality ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

doped women and drunken men. I want you to put this matter in the hands of your most experienced men and whatever the cost will be, find out the truth about this Club and if it is as bad as I am informed prosecute it with the utmost rigour of the law’.

All of this was satirised in A.P. Herbert

Sir Alan Patrick Herbert Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (A. P. Herbert, 24 September 1890 – 11 November 1971), was an English humorist, novelist, playwright, law reformist, and in 1935–1950 an Independent (politician), independent Mem ...

’s one act play ''The Two Gentlemen of Soho'' (1927).

General Strike and subversion

In 1925, he ordered a show trial ofHarry Pollitt

Harry Pollitt (22 November 1890 – 27 June 1960) was a British communist who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) from 1929 to September 1939 and again from 1941 until his death in 1960. Pollitt spen ...

and a dozen other leading communists, using the Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797

The Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797 (37 Geo 3 c 70) was an Act passed by the Parliament of Great Britain. The Act was passed in the aftermath of the Spithead and Nore mutinies and aimed to prevent the seduction of sailors and soldiers to commit mu ...

.Matthew 2004, p40 During the General Strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governmen ...

, he was a leading organiser of the systems that maintained supplies and law and order, although there is some evidence that left to himself he would have pursued a more hawkish policy – most notably, his repeated appeals for more volunteer constables and his attempt to close down the '' Daily Herald''.

Having been a hardliner during the General Strike he remained a staunch anti-communist thereafter, although the left appear to have warmed a little to him over the Prayer Book controversy. Against the wishes of Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain he ordered a police raid on the Soviet trade agency ARCOS in 1927, apparently actually hoping to rupture Anglo-Soviet relations. He was popular with the police and on his retirement a portrait of him was erected in Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

, paid for by police subscription.Matthew 2004, p40

Revised Prayer Book

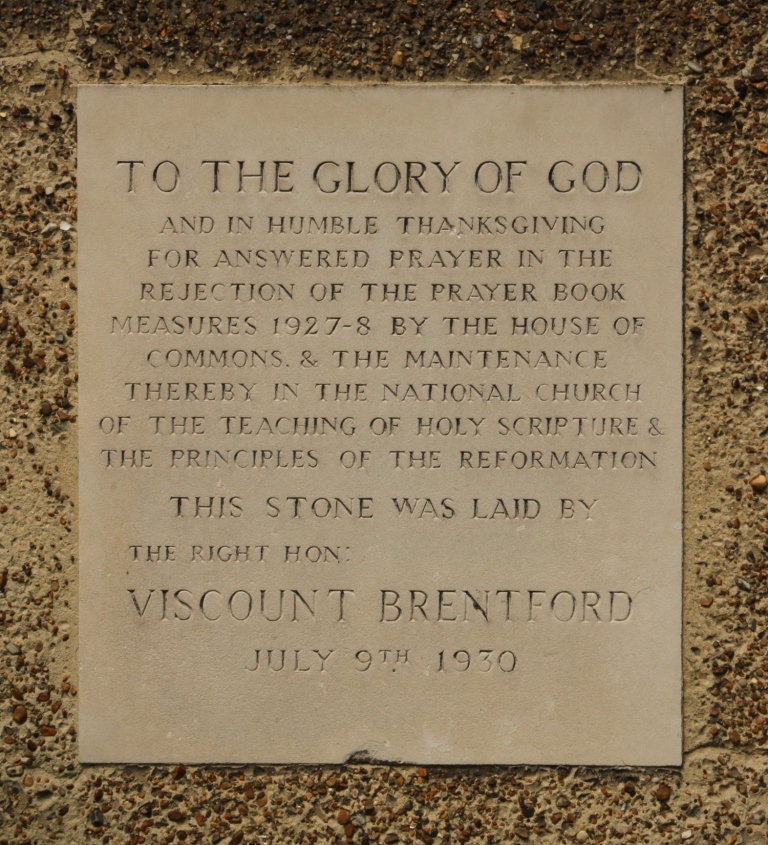

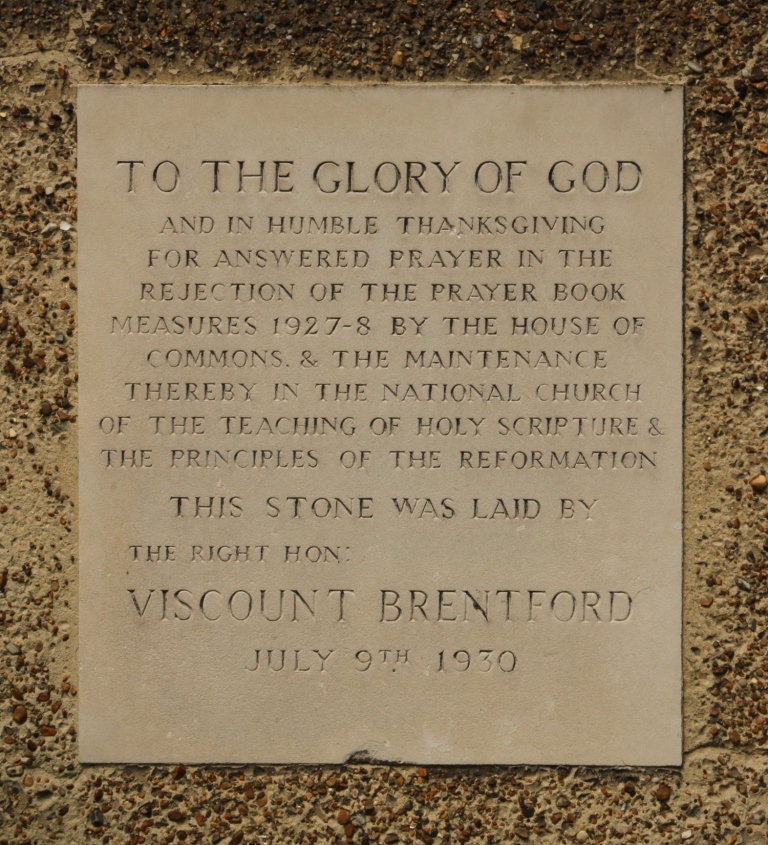

In 1927 Joynson-Hicks turned his fire on the proposed revision of the ''

In 1927 Joynson-Hicks turned his fire on the proposed revision of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

''. The law required Parliament to approve such revisions, normally regarded as a formality.Ross McKibbin

Ross Ian McKibbin, FBA (born January 1942) is an Australian academic historian whose career, spent almost entirely at the University of Oxford, has been devoted to studying the social, political and cultural history of modern Britain, especially f ...

, ''Classes and Cultures: England 1918–1951'' (Oxford 1998) pp. 277–278 Joynson-Hicks had been President of the evangelical National Church League

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

since 1921, and he went against Baldwin’s wishes in opposing the Revised Prayer Book.

When the Prayer Book came before the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

Joynson-Hicks argued strongly against its adoption as he felt it strayed far from the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

principles of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. He likened the Revised Prayer Book to "papistry", as he believed that the reservation of sacrament implied a belief in transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of th ...

. The debate on the Prayer Book is regarded as one of the most eloquent ever seen in the Commons, and resulted in the rejection of the revised Prayer Book in 1927. His allies were an alliance of ultra-Protestant Tories and nonconformist Liberals and Labour, and some of them likened him to John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of th ...

or Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

. It was said that no such occasion had been seen since the anti-Catholic agitation of 1850-1 or, some said, since the late seventeenth century crises over Exclusion

Exclusion may refer to:

Legal or regulatory

* Exclusion zone, a geographic area in which some sanctioning authority prohibits specific activities

* Exclusion Crisis and Exclusion Bill, a 17th-century attempt to ensure a Protestant succession in En ...

or Titus Oates

Titus Oates (15 September 1649 – 12/13 July 1705) was an English priest who fabricated the " Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.

Early life

Titus Oates was born at Oakham in Rutland. His father Samuel (1610� ...

.

A further revised version (the "Deposited Book") was submitted in 1928 but rejected again.Matthew 2004, pp39-40

Many leading Church of England figures came to feel that disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular stat ...

would become necessary to guard the Church against this sort of political interference. Joynson-Hicks' book ''The Prayer Book Crisis'', published in May 1928, correctly forecast that the bishops would back off from demanding disestablishment, for fear of losing their state-provided salaries and endowments. However, the National Assembly of the Church of England then declared an emergency, and this was argued as a pretext for the use of the 1928 Prayer Book in many churches for decades afterwards, an act of questionable legality.

Votes for young women

Off the cuff and without Cabinet discussion, in a debate on a private member's bill on 20 February 1925, Joynson-Hicks pledged equal voting rights for women (clarifying a pronouncement of Baldwin's in the 1924 General Election). Joynson-Hicks' 1933 biographer wrote that the claim that Joynson-Hicks' parliamentary pledge toLady Astor

Nancy Witcher Langhorne Astor, Viscountess Astor, (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945.

Astor's first husband was America ...

in 1925 had committed the party to giving votes to young women was an invention of Winston Churchill that has entered popular mythology but has no basis in fact.Taylor

Taylor, Taylors or Taylor's may refer to:

People

* Taylor (surname)

**List of people with surname Taylor

* Taylor (given name), including Tayla and Taylah

* Taylor sept, a branch of Scottish clan Cameron

* Justice Taylor (disambiguation)

Plac ...

, pp. 282–285 However, Francis Thompson (2004) wrote that the Baldwin Government would probably not have taken action without Joynson-Hicks' pledge.

Joynson-Hicks personally moved the Second Reading of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928

The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This act expanded on the Representation of the People Act 1918 which had given some women the vote in Parliamentary elections for the ...

and was also responsible for piloting it through Parliament. He made a strong speech in support of the Bill, which lowered the voting age for women from 30 to 21 (the same age as men at the time), and which was blamed in part for the Conservatives' unexpected electoral defeat the following year, which the right of the party attributed to newly enfranchised young women (referred to derogatorily as "flappers") voting for the opposition Labour party.

Reforms

Throughout his tenure at the Home Office, Joynson-Hicks was involved in the reform of the penal system – in particular, theBorstal

A Borstal was a type of youth detention centre in the United Kingdom, several member states of the Commonwealth and the Republic of Ireland. In India, such a detention centre is known as a Borstal school.

Borstals were run by HM Prison Service ...

s and the introduction of a legal requirement for all courts to have a probation officer

A probation and parole officer is an official appointed or sworn to investigate, report on, and supervise the conduct of convicted offenders on probation or those released from incarceration to community supervision such as parole. Most probati ...

. He made a point of visiting all the prisons in the country, and was often dismayed by what he found there. He made a concerted effort to improve the conditions of the prisons under his jurisdiction, and earned a compliment from persistent offender and night-club owner Kate Meyrick, who noted in her memoirs that prisons had improved considerably thanks to his efforts.

Joynson-Hicks sided with Churchill over the General Strike and India, but parted company with him on the topic of greyhound racing, which Joynson-Hicks believed served a useful social function in getting poor people out of the pubs. He also thought that Churchill's view that totalisers were permissible for horse-racing but not for greyhounds smacked of one law for the rich and another for the poor.

He became something of a hero to shop workers because of the Shops (Hours of Closing) Act 1928, which banned working after 8pm and required employers to grant a half day holiday each week. He also repealed a regulation to allow chocolates to be sold in the ''first'' interval of theatre performances as well as the second.

In August 1928, Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

thought Joynson-Hicks the only possible successor to Baldwin. However, he was a figure of fun to many of the public and most of his colleagues thought the idea of him as Prime Minister, in FML Thompson's view, "ridiculous". He was praised in the popular press and ridiculed in the upmarket weeklies. He insisted that he did not favour full censorship, and in his 1929 pamphlet ''Do We Need A Censor?'' he recorded that he had ordered the police to stamp out indecency in Hyde Park so that it would be safe for "a man to take his daughter for a walk" there.

Later life

As the time for a new general election loomed, Baldwin contemplated reshuffling his Cabinet to move Churchill from the Exchequer to the India Office, and asking all ministers older than himself (Baldwin was born in 1867) to step down, with the exception of Sir Austen Chamberlain. Joynson-Hicks would have been one of those asked to retire from the Cabinet if the Conservatives had been re-elected. The Conservatives unexpectedly lost power at the general election in May1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

. A month after the election Joynson-Hicks was raised to the peerage as the Viscount Brentford, of Newick

Newick is a village, civil parish and electoral ward in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. It is located on the A272 road east of Haywards Heath.

The parish church, St. Mary's, dates mainly from the Victorian era, but still has a Nor ...

in the County of Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English C ...

in the Dissolution Honours

Crown Honours Lists are lists of honours conferred upon citizens of the Commonwealth realms. The awards are presented by or in the name of the reigning monarch, currently King Charles III, or his vice-regal representative.

New Year Honours

Ho ...

(necessitating a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

at which the Conservatives narrowly held his old seat).

Lord Brentford remained a senior figure in the Conservative Party, but due to his declining health he was not invited to join the National Government at its formation in August 1931. As late as October 1931 Lord Beaverbrook urged him to set up a Conservative Shadow Cabinet, as an alternative to the National Government. The National Government was reconstructed in November 1931, but again he was not offered a return to office.

Family

Lord Brentford married Grace Lynn, only daughter of Richard Hampson Joynson, JP, of BowdonCheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, on 12 June 1895 in St. Margaret's Church, Westminster

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster a ...

. They had two sons and one daughter.

Joynson-Hicks died at Newick Park, Sussex, on 8 June 1932, aged 66. His wealth at death was £67,661 5s 7d (around £4m at 2016 prices).

His widow the Viscountess Brentford died in January 1952. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Richard. His youngest son, the Hon. Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

(who succeeded in the viscountcy in 1958), was also a Conservative politician.

Reputation

Joynson-Hicks' Victorian top hat and frock coat made him seem an old-fashioned figure, but he came to be regarded with a certain affection by the public. William Bridgeman, his predecessor as Home Secretary, wrote of him "There is something of the comedian in him, which is not intentional but inevitably apparent, which makes it hard to take him as seriously as one might". Churchill wrote of him "The worst that can be said about him is that he runs the risk of being most humorous when he wishes to be most serious". After his death Leo Amery wrote that "he was a very likeable fellow" whilst Stanley Baldwin observed "he may have said many foolish things but he rarely did one". Although Joynson-Hicks was Home Secretary, a notoriously difficult office to hold, for some four and a half years, he is frequently overlooked by both historians and politicians. His length of tenure was exceeded in the twentieth century only byChuter Ede

James Chuter Ede, Baron Chuter-Ede of Epsom, (11 September 1882 – 11 November 1965), was a British teacher, trade unionist and Labour Party politician. He served as Home Secretary under Prime Minister Clement Attlee from 1945 to 1951, becomi ...

, R. A. Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party politician. ''The Times'' obituary ...

and Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Mini ...

, yet he was not included in a list of long-serving Home Secretaries presented to Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

in 2001 on his departure from the Home Office. He is also virtually the only major politician of the 1920s not to have been accorded a recent biography.

For many years detailed discussion of Joynson-Hicks' life and career was hampered by the inaccessibility of his papers, which were kept by the Brentford family. This meant the discourse on his life was shaped by the official biography of 1933 by H. A. Taylor, and by material published by his contemporaries – much of it published by people who hated him. As a result, public discourse has been shaped by material that portrayed him in an unflattering light, such as Ronald Blythe's biographical chapter in ''The Age of Illusion.''

In the 1990s the current Viscount lent his grandfather's papers to an MPhil student at the University of Westminster

, mottoeng = The Lord is our Strength

, type = Public

, established = 1838: Royal Polytechnic Institution 1891: Polytechnic-Regent Street 1970: Polytechnic of Central London 1992: University of Westminster

, endowment = £5.1 million ...

, Jonathon Hopkins, who prepared a catalogue of them and wrote a short biography of Joynson-Hicks as part of his thesis. In 2007, a number of these papers were deposited with the East Sussex Record Office in Lewes (which transferred to The Keep in Brighton in 2013) where they are available to the public. Huw Clayton, whose PhD thesis concerned Joynson-Hicks' moral policies at the Home Office, has announced that he plans to write a new biography of Joynson-Hicks with the aid of these sources. An article on Joynson-Hicks, written by Clayton, has since appeared in the ''Journal of Historical Biography''.

Arms

References

Bibliography

* * * , essay on Joynson-Hicks written by FML Thompson *Further reading

*Alderman, Geoffrey, "Recent Anglo-Jewish Historiography and the Myth of Jix's Anti-Semitism: A Response" ''Australian Journal of Jewish Studies'' 8:1 (1994) * – "The Anti-Jewish Career of Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Cabinet Minister,' ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 24 (1989) pp. 461–482 *Joynson-Hicks, William, The Prayer Book Crisis. London: Putnam, 1928 *Perkins, Anne, ''A Very British Strike: 3–12 May 1926'' London 2006 *- "Professor Alderman and Jix: A Response" ''Australian Journal of Jewish Studies'' 8:2 (1994) pp. 192–201 * Sydney Robinson, W., ''The Last Victorians: a daring reassessment of four twentieth century eccentrics: Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Dean Inge, Lord Reith and Sir Arthur Bryant'' London 2014 * Other sources on Joynson-Hicks: * *Hopkins, Jonathon M., "Paradoxes Personified: Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Viscount Brentford and the conflict between change and stability in British Society in the 1920s" University of Westminster MPhil thesis (1996): copy available at the East Sussex Record Office. *National Register of Archives: Accessions to Repositories 2007: East Sussex Record Office: link to ESRO website:External links

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brentford, William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount 1865 births 1932 deaths Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Deputy Lieutenants of Norfolk Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William Joynson-Hicks, William UK MPs who were granted peerages Evangelical Anglicans Viscounts created by George V