Sir Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, (13 April 1593 ( N.S.)12 May 1641), was an

The 1st Viscount Wentworth, as he had become, became a

The 1st Viscount Wentworth, as he had become, became a  Wentworth ignored Charles' promise that no colonists would be awarded land, to the detriment of Catholic landholders, in

Wentworth ignored Charles' promise that no colonists would be awarded land, to the detriment of Catholic landholders, in

The Commons insisted on peace with the Scots. Charles, on the advice of—or perhaps by the treachery of—

The Commons insisted on peace with the Scots. Charles, on the advice of—or perhaps by the treachery of— By late 1640, there was no option but to call a new Parliament. The

By late 1640, there was no option but to call a new Parliament. The

However tyrannical Strafford's earlier conduct may have been, his offence was outside the definition of

However tyrannical Strafford's earlier conduct may have been, his offence was outside the definition of

Strafford met his fate two days later on

Strafford met his fate two days later on

online

* Cooper, Elizabeth, ''The Life of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford'' (2 vol 1874

online

* * Orr, D. Alan. '' Treason and the State'' (2002): pp 61–100 on Wentworth

online

* Wedgwood, C. V. "The lost archangel a new view of Strafford" ''History Today'' (1951) 1#1 pp 18–24 online.

* ttp://www.york.ac.uk/univ/coll/went Wentworth Graduate College of the University of York, named in honor of Thomas Wentworth* *

Portrait of the Earl of Strafford in the UK Parliamentary CollectionsList of Strafford's visitors in the Parliamentary ArchivesPetition of the Earl of Strafford in the Parliamentary ArchivesThe Earl of Strafford's Act of Attainder in the Parliamentary Archives

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Strafford, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl Of 1593 births 1641 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Members of the Inner Temple English soldiers English Anglicans People convicted under a bill of attainder Executions at the Tower of London Knights of the Garter Lord-Lieutenants of Yorkshire Lords Lieutenant of Ireland Executed military leaders Executed people from London People executed by Stuart England by decapitation High Sheriffs of Yorkshire English MPs 1614 English MPs 1621–1622 English MPs 1624–1625 English MPs 1625 English MPs 1628–1629 English politicians convicted of crimes Earls of Strafford (1640 creation)

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

statesman and a major figure in the period leading up to the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. He served in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and was a supporter of King Charles I. From 1632 to 1640 he was Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

, where he established a strong authoritarian rule. Recalled to England, he became a leading advisor to the King, attempting to strengthen the royal position against Parliament. When Parliament condemned Lord Strafford to death, Charles reluctantly signed the death warrant

An execution warrant (also called death warrant or black warrant) is a writ that authorizes the execution of a condemned person. An execution warrant is not to be confused with a " license to kill", which operates like an arrest warrant but ...

and Strafford was executed. He had been advanced several times in the Peerage of England

The Peerage of England comprises all peerages created in the Kingdom of England before the Act of Union in 1707. In that year, the Peerages of England and Scotland were replaced by one Peerage of Great Britain. There are five peerages in t ...

during his career, being created 1st Baron Wentworth in 1628, 1st Viscount Wentworth in 1629, and, finally, 1st Earl of Strafford

Earl of Strafford is a title that has been created three times in English and British history.

The first creation was in the Peerage of England in January 1640 for Thomas Wentworth, the close advisor of King Charles I. He had already succe ...

in January 1640. He was known as Sir Thomas Wentworth, 2nd Baronet, between 1614 and 1628.

Early life

Wentworth was born in London. He was the son ofSir William Wentworth, 1st Baronet

Sir William Wentworth (1562-1614) was an English landowner.

He was born in 1562, the son of Thomas Wentworth and Margaret Gascoigne or Gascoyne, heiress of Gawthorpe. A story was told of Wentworth's visit to Bolling Hall and a vision concerning S ...

, of Wentworth Woodhouse

Wentworth Woodhouse is a Grade I listed country house in the village of Wentworth, in the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, England. It is currently owned by the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust. The building has m ...

, near Rotherham

Rotherham () is a large minster and market town in South Yorkshire, England. The town takes its name from the River Rother which then merges with the River Don. The River Don then flows through the town centre. It is the main settlement of ...

, a member of an old Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

family, and of Anne, daughter of Sir Robert Atkins of Stowell, Gloucestershire. He was educated at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

, became a law student at the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

in 1607, and in 1611 was knighted. He married firstly Margaret, daughter of Francis Clifford, Earl of Cumberland

The title of Earl of Cumberland was created in the Peerage of Peerage of England, England in 1525 for the 11th Baron de Clifford.''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press'', 2004. It became extinct in 1643. The Duke of C ...

and Grisold Hughes.

Early Parliamentary career

The young Sir Thomas Wentworth, 2ndBaronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

, entered the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

in 1614 as Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

's representative in the "Addled Parliament

The Parliament of 1614 was the second Parliament of England of the reign of James VI and I, which sat between 5 April and 7 June 1614. Lasting only two months and two days, it saw no bills pass and was not even regarded as a Parliament by its c ...

", but it was not until the parliament of 1621, in which he sat for the same constituency, that he took part in a debate. His position was ambivalent. He did not sympathise with the zeal of the popular party for war with Spain, favoured by George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 28 August 1592 – 23 August 1628), was an English courtier, statesman, and patron of the arts. He was a favourite and possibly also a lover of King James I of England. Buckingham remained at the ...

, James I's foremost advisor and favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

, but James's denial of the rights and privileges of parliament seems to have caused Wentworth to join in the vindication of the claims of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and he supported the protestation which dissolved the third parliament of James.

In 1622 Wentworth's first wife Margaret Clifford died. Wentworth, according to his friends, was deeply grieved by her death; but in February 1625 he married Arabella Holles, daughter of John Holles, 1st Earl of Clare

John Holles, 1st Earl of Clare (May 1564 – 4 October 1637) was an English nobleman.

He was the son of Denzil Holles of Irby upon Humber and Eleanor Sheffield (daughter of Edmund Sheffield, 1st Baron Sheffield of Butterwick). His great-grandfat ...

and Anne Stanhope: a marriage which was generally believed to be a true love affair on both sides. He represented Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

in the Happy Parliament

The 4th Parliament of King James I was the fourth and last Parliament of England of the reign of James I of England, summoned on 30 December 1623, sitting from 19 February 1624 to 29 May 1624, and thereafter kept out of session with repeated pror ...

of 1624, but appears to have taken no active part. He expressed a wish to avoid foreign complications and "do first the business of the commonwealth".

In the first parliament of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, in June 1625, Wentworth again represented Yorkshire, and showed his hostility to the proposed war with Spain by supporting a motion for an adjournment before the house proceeded to business. He opposed the demand for war subsidies made on Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of Central Milton Keynes, sou ...

's behalf—after the death of James I, Buckingham had become first minister to Charles—and after Parliament was dissolved in November he was made High Sheriff of Yorkshire

The Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the Sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of the responsibilities associated with the post have been transferred elsewhere ...

, a position which excluded him from the parliament which met in 1626. Yet he had never taken up an attitude of antagonism to the King. His position was very different from that of the regular opposition. He was anxious to serve the Crown, but he disapproved of the King's policy.

In January 1626 Wentworth asked for the presidency of the Council of the North

The Council of the North was an administrative body first set up in 1484 by King Richard III of England, to improve access to conciliar justice in Northern England. This built upon steps by King Edward IV of England in delegating authority in the ...

, and was favourably received by Buckingham. But after the dissolution of the parliament, he was dismissed from the justiceship of the peace and the office of ''custos rotulorum

''Custos rotulorum'' (; plural: ''custodes rotulorum''; Latin for "keeper of the rolls", ) is a civic post that is recognised in the United Kingdom (except Scotland) and in Jamaica.

England, Wales and Northern Ireland

The ''custos rotulorum'' is t ...

'' of Yorkshire—which he had held since 1615—probably because he would not support the court in forcing the country to contribute money without a parliamentary grant. In 1627, he refused to contribute to the forced loan, and was subsequently imprisoned.

The Petition of Right and its aftermath

In 1628, Wentworth was one of the more vocal supporters of thePetition of Right

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689. It was part of a wider c ...

, which attempted to curb the power of the King. Once Charles had grudgingly accepted the Petition, Wentworth felt it appropriate to support the crown, saying, "The authority of a king is the keystone which closeth up the arch of order and government". He was consequently branded a turncoat.

In the parliament of 1628, Wentworth joined the popular leaders in resistance to arbitrary taxation and imprisonment, but tried to obtain his goal without offending the Crown. He led the movement for a bill which would have secured the liberties of the subject as completely as the Petition of Right afterwards did, but in a manner less offensive to the King. The proposal failed because of both the uncompromising nature of the parliamentary party and Charles's stubborn refusal to make concessions, and the leadership was snatched from Wentworth's hands by John Eliot and Edward Coke

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

. Later in the session, he quarrelled with Eliot because Wentworth wanted to come to a compromise with the Lords, so as to leave room for the King to act unchecked in special emergencies.

On 22 July 1628, not long after the prorogation, Wentworth was created Baron Wentworth, and received the promise of the presidency of the Council of the North

The Council of the North was an administrative body first set up in 1484 by King Richard III of England, to improve access to conciliar justice in Northern England. This built upon steps by King Edward IV of England in delegating authority in the ...

at the next vacancy. This implied no change of principle. He was now at variance with the Parliamentary Party on two great subjects of policy, disapproving both of the intention of Parliament to take the powers of the executive and also of its inclination towards Puritanism. When once the breach was made it naturally grew wider, partly from the energy each party put into its work, and partly from the personal animosities which arose.

As yet Wentworth was not directly involved in the government of the country. However, following the assassination of Buckingham, in December 1628, he became Viscount Wentworth and not long afterwards president of the Council of the North

The Council of the North was an administrative body first set up in 1484 by King Richard III of England, to improve access to conciliar justice in Northern England. This built upon steps by King Edward IV of England in delegating authority in the ...

. In the speech delivered at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

on taking office, he announced his intention, almost in the words of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, of doing his utmost to bind up the prerogative of the Crown and the liberties of the subject in an indistinguishable union. "Whoever", he said, "ravels forth into questions the right of a king and of a people shall never be able to wrap them up again into the comeliness and order he found them". His tactics were the same as those he later practised in Ireland, leading to the accusation that he planned to centralise all power with the executive at the expense of the individual in defiance of constitutional liberties.

The parliamentary session of 1629 ended in a breach between the King and Parliament, which made the task of a moderator hopeless. Wentworth had to choose between either helping the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

dominate the King or helping the King to dominate the House of Commons. He chose the latter course, throwing himself into the work of repression with characteristic energy and claiming that he was maintaining the old constitution and that his opponents in Parliament were attempting to alter it by claiming supremacy for Parliament. From this time on, he acted as one of two principal members (the other being Archbishop William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

) in a team of key royal advisors (the "Thorough Party") during an 11-year period of total monarchical rule without parliament (known both as "the Personal Rule

The Personal Rule (also known as the Eleven Years' Tyranny) was the period from 1629 to 1640, when King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland ruled without recourse to Parliament. The King claimed that he was entitled to do this under the Roya ...

" and the "eleven-year tyranny").

Lord Deputy of Ireland

The 1st Viscount Wentworth, as he had become, became a

The 1st Viscount Wentworth, as he had become, became a privy counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a privy council, formal body of advisers to the British monarchy, sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises Politics of the United King ...

in November 1629. On 12 January 1632 he was made Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

, arriving in Dublin in July the following year. He had recently suffered the loss of his beloved second wife Arabella in childbirth. Despite his genuine grief for Arabella, his third marriage to Elizabeth Rhodes in 1632 was also a happy one; but through a strange lapse of judgement, he did not announce it publicly for almost a year, by which time damaging rumours about the presence of a young woman in his house (who was reputed to be his mistress) had gained wide circulation. Wedgwood remarks that it was typical of Wentworth to be oblivious to the bad impression which actions like this might make on the public. Gossip later linked his name with that of Eleanor Loftus, daughter-in-law of The 1st Viscount Loftus, Lord Chancellor of Ireland

The Lord High Chancellor of Ireland (commonly known as Lord Chancellor of Ireland) was the highest judicial office in Ireland until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. From 1721 to 1801, it was also the highest political office of ...

, but although a warm friendship existed between them, and her death in 1639 caused him much grief, there is no evidence that their relationship went beyond friendship.

In his government here he proved to be an able ruler. "The lord deputy of Ireland", wrote Sir Thomas Roe

Sir Thomas Roe ( 1581 – 6 November 1644) was an English diplomat of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. Roe's voyages ranged from Central America to India; as ambassador, he represented England in the Mughal Empire, the Ottoman Empire ...

to Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 159613 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. Since her husband's reign in Bohemia lasted for just one winter, she is called the Win ...

, "doth great wonders and governs like a king, and hath taught that kingdom to show us an example of envy, by having parliaments and knowing wisely how to use them." He reformed the administration, summarily dismissing the inefficient English officials. He succeeded in so manipulating the parliaments that he obtained the necessary grants, and secured their cooperation in various useful legislative enactments. He started a new victualling trade with Spain, promoted linen manufacture, and encouraged the development of the resources of the country in many directions. The Court of Castle Chamber

The Court of Castle Chamber (which was sometimes simply called ''Star Chamber'') was an Irish court of special jurisdiction which operated in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

It was established by Queen Elizabeth I in 1571 to deal with ca ...

, the Irish counterpart of the Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judic ...

, which up to that time had only operated intermittently, was transformed into a regular and efficient part of the Irish administration.

Customs duties rose from a little over £25,000 in 1633–34 to £57,000 in 1637–38. Wentworth raised an army, put an end to piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

, imposed Arminian

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Re ...

reforms onto the Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

-dominated Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

, and launched a campaign to win back Church lands lost during the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. His strong administration reduced the tyranny of the wealthy over the poor. Yet these measures were all carried out by arbitrary methods which made them unpopular. Their aim was not the prosperity of the Irish but the benefit to the English exchequer

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty’s Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''current account'' (i.e., money held from taxation and other government reven ...

, and Wentworth suppressed the trade in cloth "lest it should be a means to prejudice that staple commodity of England." Castle Chamber, like its model Star Chamber, was accused of brutal and arbitrary proceedings. Individual cases of unfairness included those of Robert Esmond, a ship's captain, and cousin of Laurence Esmonde, Lord Esmonde

Sir Laurence Esmonde, 1st Baron Esmonde (1570?–1646), was an Irish peer who held office as governor of the fort of Duncannon in County Wexford. He was a leading Irish Royalist commander in the English Civil War, but was later suspected of disloya ...

, accused of customs evasions, whom Wentworth was alleged to have assaulted, so causing his death, Lord Chancellor Loftus and Lord Mountnorris, the last of whom Wentworth caused to be sentenced to death to obtain the resignation of his office, and then pardoned. Promises of legislation such as the concessions known as ' The Graces' were not kept.

Wentworth ignored Charles' promise that no colonists would be awarded land, to the detriment of Catholic landholders, in

Wentworth ignored Charles' promise that no colonists would be awarded land, to the detriment of Catholic landholders, in Connaught

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbh ...

. In 1635 he raked up an obsolete title—the grant in the 14th century of Connaught to Lionel of Antwerp

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, (; 29 November 133817 October 1368) was the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of the English king Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. He was named after his birthplace, at Antwerp in the Duch ...

, whose heir Charles was—and insisted upon the grand juries finding verdicts for the King. One county only, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, resisted, and the confiscation of Galway was effected by the Court of Exchequer, while Wentworth fined the sheriff £1,000 for summoning such a jury, and cited the jurymen to the Castle Chamber to answer for their offence. In Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

the arbitrary confiscation of the property of the city companies aroused dangerous animosity against the government. His actions in Galway led to a clash with the powerful Burke family, headed by the ageing Richard Burke, Earl of Clanricarde

Earl of Clanricarde (; ) is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Ireland, first in 1543 and again in 1800. The former creation became extinct in 1916 while the 1800 creation is extant and held by the Marquess of Sligo since 191 ...

. Clanricarde's death was said by some to have been hastened by the clash: Wentworth, on hearing these reports, said he could hardly be blamed for the fact that Clanricarde was nearly seventy. It was, however, unwise to have made an enemy of the new Earl, Ulick Burke, 5th Earl of Clanricarde, who through his mother Frances Walsingham

Frances Burke, Countess of Clanricarde, Dowager Countess of Essex ( Walsingham, formerly Devereux and Sidney; 1567 – 17 February 1633) was an English noblewoman. The daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I's Secretary of State, ...

had powerful English connections: Clanricarde's half-brother, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, KB, PC (; 11 January 1591 – 14 September 1646) was an English Parliamentarian and soldier during the first half of the 17th century. With the start of the Civil War in 1642, he became the first Captain ...

, by 1641 was to become one of Wentworth's (who became Earl of Strafford in 1640) most implacable enemies.

Wentworth made many enemies in Ireland, but none more dangerous than Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork

Earl of Cork is a title in the Peerage of Ireland, held in conjunction with the Earldom of Orrery since 1753. It was created in 1620 for Richard Boyle, 1st Baron Boyle. He had already been created Lord Boyle, Baron of Youghal, in the County ...

, the most powerful of the "New English" magnates. A more diplomatic man than Wentworth would no doubt have sought Cork's friendship, but Wentworth saw Cork's great power as a threat to the Crown's central authority, and was determined to curb it. He prosecuted Lord Cork in Castle Chamber for misappropriating the funds of Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long and narrow layout. ...

College; and ordered him to take down the tomb of his first wife in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

Saint Patrick's Cathedral ( ir, Ard-Eaglais Naomh Pádraig) in Dublin, Ireland, founded in 1191 as a Roman Catholic cathedral, is currently the national cathedral of the Church of Ireland. Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, Christ Church Cathedr ...

. Cork, a patient and implacable enemy, worked quietly for Wentworth's downfall, and in 1641 recorded calmly in his diary that Wentworth (by then Earl of Strafford) had been beheaded "as he well deserved".

Toward the native Irish, Wentworth had no notion of developing their qualities by a process of natural growth; his only hope for them lay in converting them into Englishmen as soon as possible. They must be made English in their habits, in their laws and in their religion. "I see plainly ... that, so long as this kingdom continues popish, they are not a people for the Crown of England to be confident of", he wrote. Although staunchly Protestant, he showed no desire to persecute Catholics: as J.P. Kenyon remarks, it was understood that so long as Catholics remained the great majority of the population, there would have to be a much larger degree of toleration than was necessary in England. He was prepared to give tacit recognition to the Catholic hierarchy, and even gave an interview to Archbishop Thomas Fleming of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, whose homely face, plain dress and lack of ostentation made a poor impression on him.

Under Wentworth's patronage, the Werburgh Street Theatre

The Werburgh Street Theatre, also the Saint Werbrugh Street Theatre or the New Theatre, was a seventeenth-century theatre in Dublin, Ireland. Scholars and historians of the subject generally identify it as the "first custom-built theatre in the c ...

, Ireland's first theatre, was opened by John Ogilby

John Ogilby (also ''Ogelby'', ''Oglivie''; November 1600 – 4 September 1676) was a Scottish translator, impresario and cartographer. Best known for publishing the first British road atlas, he was also a successful translator, noted for publishi ...

, a member of his household, and survived for several years despite the opposition of Archbishop James Ussher

James Ussher (or Usher; 4 January 1581 – 21 March 1656) was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, who today is most famous for his ident ...

of Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

. James Shirley

James Shirley (or Sherley) (September 1596 – October 1666) was an English dramatist.

He belonged to the great period of English dramatic literature, but, in Charles Lamb's words, he "claims a place among the worthies of this period, not so m ...

, the English dramatist, wrote several plays for it, one with a distinctively Irish theme, and ''Landgartha'', by Henry Burnell

Henry Burnell (c. 1540–1614) was an Irish judge and politician; he served briefly as Recorder of Dublin and as a justice of the Court of King's Bench. Though he was willing to accept Crown office, he spent much of his career in opposition to t ...

, the first known play by an Irish dramatist, was produced there in 1640.

Wentworth's heavy-handed approach did yield some improvements, as well as contribute to the strength of the royal administration in Ireland. His hindrance in 1634 of 'The Graces', a campaign for equality by Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two chamb ...

, lost him goodwill but was based on fiscal and not religious principles. Wentworth regarded the proper management of Parliament as a crucial test of his success, and in the short term, his ruthless methods did produce results. Having settled on Nathaniel Catelyn

Sir Nathaniel Catelyn (c. 1580 – 1637) (whose family name is also spelt Catlyn or Catlin), was a leading English-born politician and judge in seventeenth-century Ireland. He was Speaker of the Irish House of Commons in the Irish Parliament of 1 ...

as the most suitable Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

, he coerced the voters of Dublin into returning him as member, and ordered the Commons to elect him Speaker. The Parliament of 1634/5 did pass some useful legislation: the Act against Fraudulent Conveyances remained in force into the 21st century. His second Parliament, however, having paid him abject compliments, began to attack his administration as soon as Wentworth left for England.

The future Duke of Ormond became Wentworth's chief friend and supporter. Wentworth planned large-scale confiscations of Catholic-owned land, both to raise money for the crown and to break the political power of the Irish Catholic gentry, a policy which Ormonde Ormonde is a surname occurring in Portugal (mainly Azores), Brazil, England, and United States. It may refer to:

People

* Ann Ormonde (born 1935), an Irish politician

* James Ormond or Ormonde (c. 1418–1497), the illegitimate son of John Butl ...

supported. Yet it infuriated Ormonde's relatives and drove many of them into opposition to Wentworth and ultimately into armed rebellion. In 1640, with Wentworth having been recalled to attend to the Second Bishops' War

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds eac ...

in England, Ormonde was made commander-in-chief of the forces in Ireland. Wedgwood concludes that whatever his intentions Wentworth/Strafford in Ireland achieved only one thing: to unite every faction in Ireland in their determination to be rid of him.

Wentworth's rule in Ireland made him more high-handed at court than ever. He had never been consulted on English affairs until February 1637 when King Charles asked Wentworth's opinion on a proposed interference in the affairs of the Continent. In reply, Wentworth assured Charles it would be unwise to undertake even naval operations till he had secured absolute power at home. He wished that Hampden and his followers "were well whipped into their right senses". The judges had given the King the right to levy ship-money

Ship money was a tax of medieval origin levied intermittently in the Kingdom of England until the middle of the 17th century. Assessed typically on the inhabitants of coastal areas of England, it was one of several taxes that English monarchs cou ...

, but, unless his majesty had "the like power declared to raise a land army, the Crown" seemed "to stand upon one leg at home, to be considerable but by halves to foreign princes abroad". When the Scottish Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

rebelled he advocated the most decided measures of repression, in February 1639 sending the King £2000 as his contribution to the expenses of the coming war, at the same time deprecating an invasion of Scotland before the English army was trained, and advising certain concessions in religion.

Wentworth apparently intended to put down roots in Ireland: in the late 1630s he was much occupied with building a mansion, Jigginstown Castle

Jigginstown Castle is a ruined 17th-century house and National Monument near Naas, County Kildare, Ireland. It was constructed in the late 1630s when Ireland was under the reign of Charles I (1625–1649). At the time it was one of the larges ...

, near Naas, County Kildare

Naas ( ; ga, Nás na Ríogh or ) is the county town of County Kildare in Ireland. In 2016, it had a population of 21,393, making it the second largest town in County Kildare after Newbridge.

History

The name of Naas has been recorded in ...

. He is thought to have intended it to be his official residence where he could entertain the King, should he visit Ireland. The castle, which was to be built partly of red brick and partly of Kilkenny

Kilkenny (). is a city in County Kilkenny, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region and in the province of Leinster. It is built on both banks of the River Nore. The 2016 census gave the total population of Kilkenny as 26,512.

Kilken ...

marble, would, had it been completed, have been probably the largest private house in Ireland, but after Wentworth's death, it quickly fell into ruin, although the ground floor still exists.

He made some efforts also to build up a network of family alliances in Ireland: his brother George, to whom he was close, married Anne Ruish, sister of Strafford's great friend Eleanor Loftus, and his sister Elizabeth married James Dillon, Earl of Roscommon

Earl of Roscommon was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 5 August 1622 for James Dillon, 1st Baron Dillon. He had already been created Baron Dillon on 24 January 1619, also in the Peerage of Ireland. The fourth Earl was a court ...

. Roscommon, unlike most of the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

nobility, remained staunchly loyal to the King during the Civil War. His son Wentworth Dillon, 4th Earl of Roscommon

Wentworth Dillon, 4th Earl of Roscommon (1637–1685), was an Anglo-Irish landlord, Irish peer, and poet.

Birth and origins

Wentworth was born in October 1637 in Dublin, probably in St George's Lane. He was the only son of James Dillon, 3rd ...

, was named for his distinguished uncle, and grew up to be a poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

of some distinction. Strafford seems to have taken some interest in his nephew's education, and he spent part of his childhood at his uncle's Yorkshire home.

Recall and impeachment

Wentworth was recalled to England in September 1639. He was expected to help sort out the problems that were growing at home: namely, bankruptcy and war with the ScottishCovenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

s, and became the King's principal adviser. Unaware how much opposition had developed in England during his absence, he recommended the calling of a parliament to support a renewal of the war, hoping that by the offer of a loan from the Privy Councillors, to which he contributed £20,000, he would save Charles from having to submit to the new parliament if it proved truculent.

The King created him Earl of Strafford in January 1640 (the Wentworth family seat of Wentworth Woodhouse

Wentworth Woodhouse is a Grade I listed country house in the village of Wentworth, in the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, England. It is currently owned by the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust. The building has m ...

lay in the hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 and preceding 101.

In medieval contexts, it may be described as the short hundred or five score in order to differentiate the English and Germanic use of "hundred" to de ...

of Strafford ( Strafforth) in the West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

) and in March he went to Ireland to hold an Irish parliament, where the Catholic vote secured a grant of subsidies to be used against the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Scots. An Irish army was to be levied to assist in the coming war. When Strafford returned to England, he found that the Commons were holding back from a grant of supply, so he tried to enlist the peers on the side of the King, and persuaded Charles to be content with a smaller grant than he had originally asked for.

From April to August 1640, on his return from Ireland, Stratford occupied the newly built Leicester House, Westminster

Leicester House was a large aristocratic townhouse in Westminster, London, to the north of where Leicester Square now is. Built by the Earl of Leicester and completed in 1635, it was later occupied by Elizabeth Stuart, a former Queen of Bohemi ...

, in the absence of its owner Lord Leicester.

The Commons insisted on peace with the Scots. Charles, on the advice of—or perhaps by the treachery of—

The Commons insisted on peace with the Scots. Charles, on the advice of—or perhaps by the treachery of—Henry Vane the Elder

Sir Henry Vane, the elder (18 February 15891655) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1614 and 1654. He served King Charles in many posts including secretary of state, but on the outbreak of the En ...

, returned to his larger demand of 12 subsidies; and on 9 May, at the privy council, Strafford, though reluctantly, voted for a dissolution. The same morning the Committee of Eight of the privy council met again. Vane and others were for a mere defence against invasion. Strafford's advice was the contrary. "Go on vigorously or let them alone ... go on with a vigorous war as you first designed, loose and absolved from all rules of government, being reduced to extreme necessity, everything is to be done that power might admit ... You have an army in Ireland you may employ here to reduce this kingdom". He tried to force the citizens of London to lend money, and supported a project for debasing the coinage

Coinage may refer to:

* Coins, standardized as currency

* Neologism, coinage of a new word

* ''COINage'', numismatics magazine

* Tin coinage, a tax on refined tin

* Protologism, coinage of a seldom used new term

See also

* Coining (disambiguatio ...

and seizing bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

(the property of foreign merchants). He also advocated the purchase of a loan from Spain by the offer of a future alliance. Strafford was now appointed to command the English army, and was made a Knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George ...

, but he fell ill at a crucial moment. In the great council of peers, which assembled on 24 September at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, the struggle was given up, and Charles announced that he had issued writs for another parliament.

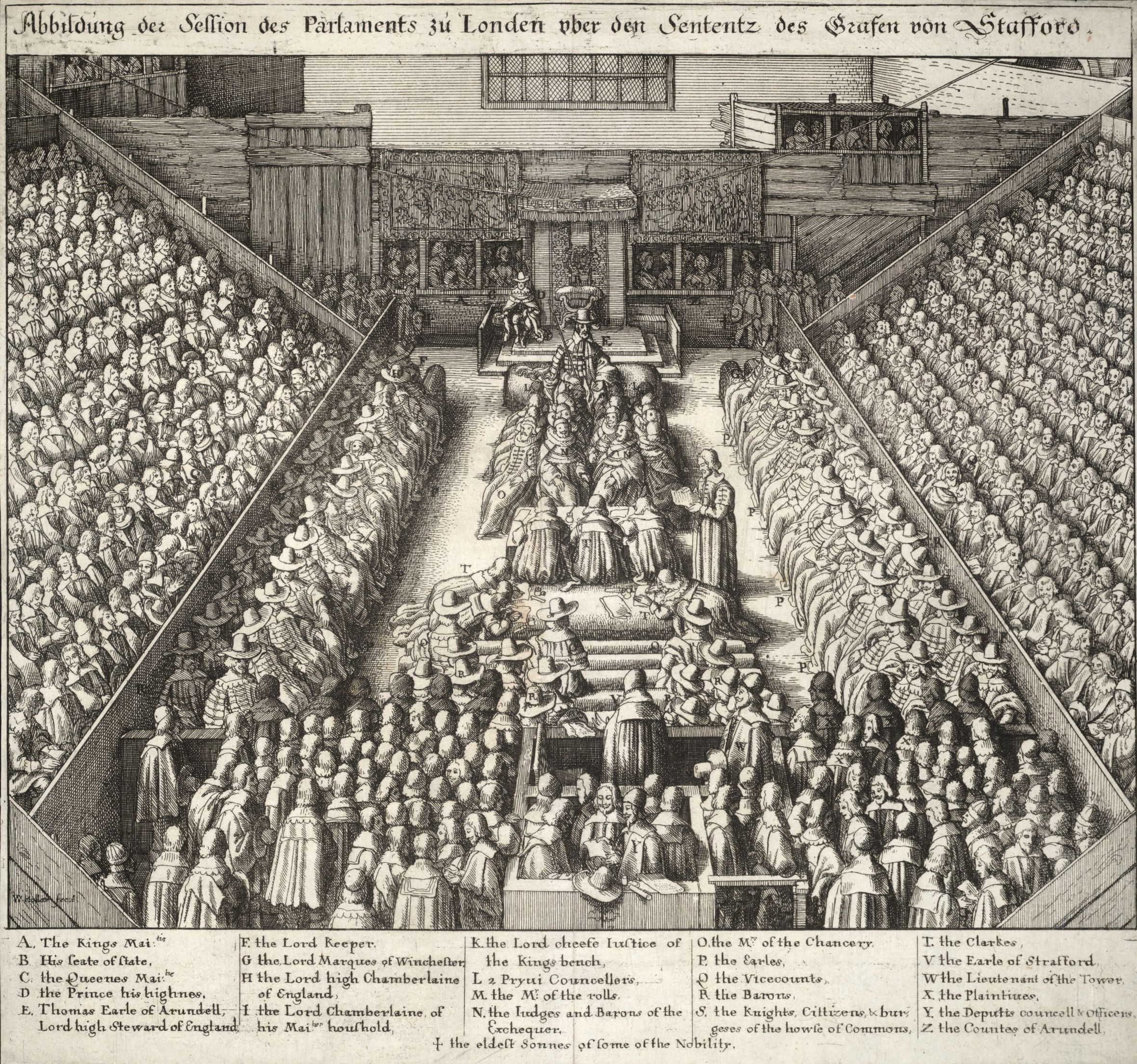

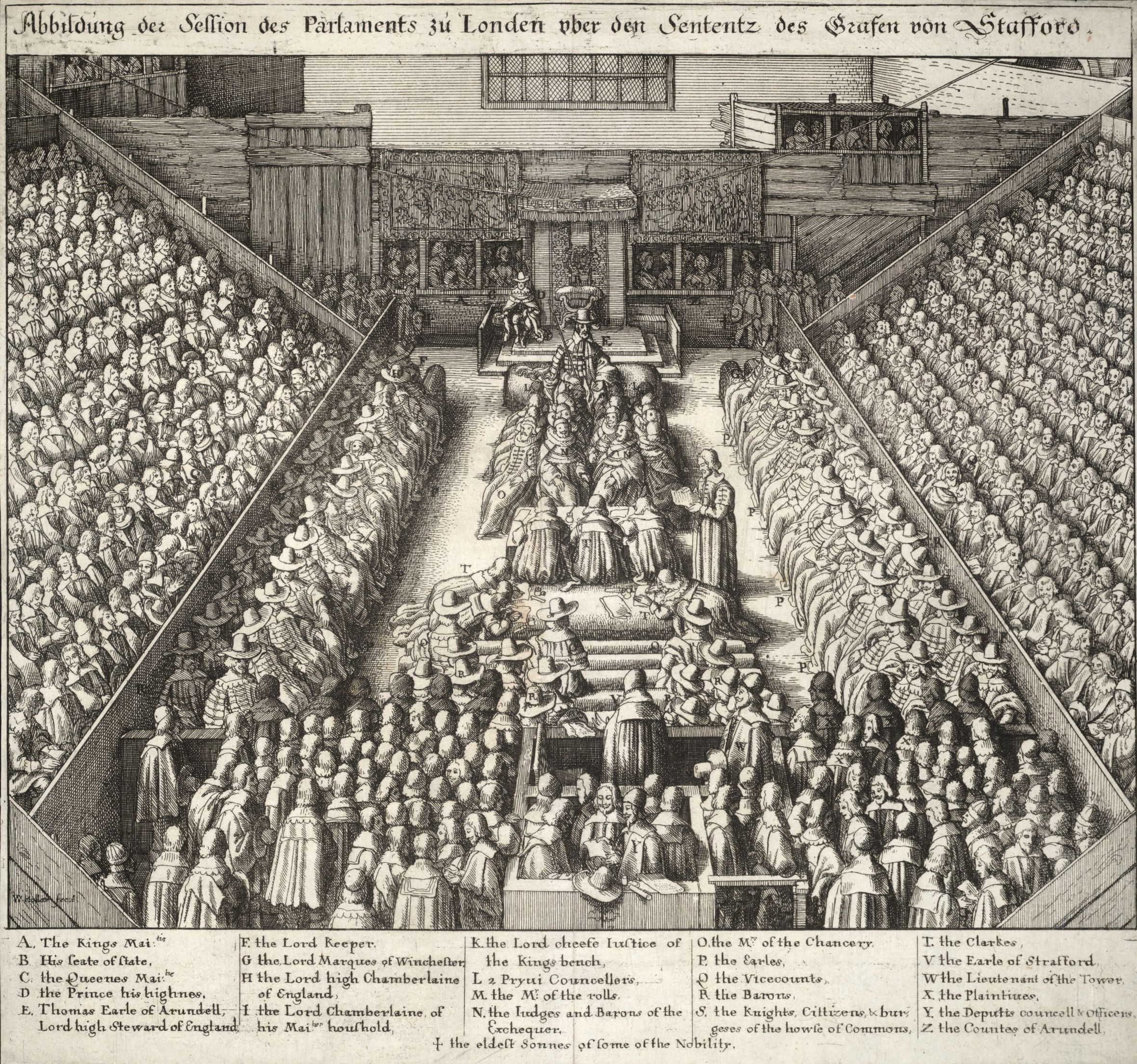

By late 1640, there was no option but to call a new Parliament. The

By late 1640, there was no option but to call a new Parliament. The Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

assembled on 3 November 1640, and Charles immediately summoned Strafford to London, promising that he "should not suffer in his person, honour or fortune". One of Parliament's first actions was to impeach

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In E ...

Strafford for "high misdemeanours" regarding his conduct in Ireland. He arrived on 9 November and the next day asked Charles I to forestall his impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

by accusing the leaders of the popular party of treasonable communications with the Scots. The plan having been betrayed, John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

immediately took up the impeachment to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

on 11 November. Strafford came in person to confront his accusers, but was ordered to withdraw and taken into custody. On 25 November his preliminary charge was brought up, whereupon he was sent to the Tower of London, and, on 31 January 1641, the accusations in detail were presented. These were that Strafford had tried to subvert the fundamental laws of the kingdom. Much stress was laid on Strafford's reported words: "You have an army in Ireland you may employ here to reduce ''this kingdom''".

The failure of impeachment and the Bill of Attainder

However tyrannical Strafford's earlier conduct may have been, his offence was outside the definition of

However tyrannical Strafford's earlier conduct may have been, his offence was outside the definition of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Although a flood of complaints poured in from Ireland, and Strafford's many enemies there were happy to testify against him, none of them could point to any act which was treasonable, as opposed to high-handed. The copy of rough notes of Strafford's speech in the committee of the council, obtained from Sir Henry Vane the Younger

Sir Henry Vane (baptised 26 March 161314 June 1662), often referred to as Harry Vane and Henry Vane the Younger to distinguish him from his father, Henry Vane the Elder, was an England, English politician, statesman, and colonial governor. He ...

, were validated by councillors who had been present on the occasion, including Henry Vane the Elder

Sir Henry Vane, the elder (18 February 15891655) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1614 and 1654. He served King Charles in many posts including secretary of state, but on the outbreak of the En ...

, who did ultimately corroborate them (but nearly disowned his own son for having found and leaked them in the first place), and partially by Algernon Percy Algernon Percy may refer to:

* Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), English military leader

* Algernon Percy, 1st Earl of Beverley (1750–1830), peer known as Lord Algernon Percy from 1766–86

*Hon. Algernon Percy (diplomat ...

, Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

. This was not evidence which would convict in a court of law, and all parties knew this. Strafford's words, particularly the crucial phrase ''this kingdom'', had to be arbitrarily interpreted as referring to the subjection of England and not of Scotland, and were also spoken on a privileged occasion. Strafford took full advantage of the weak points in his attack on the evidence collected. Over and over Strafford pointed to the fundamental weakness in the prosecution: how could it be ''treason'' to carry out the King's wishes? The lords, his judges, were influenced in his favour. The impeachment failed on 10 April 1641. Pym and his allies increased public pressure, threatening members of Parliament unless they punished Strafford.

The Commons, therefore, feeling their victim slipping from their grasp, dropped the impeachment, and brought in and passed a bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder or writ of attainder or bill of penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and punishing them, often without a trial. As with attai ...

on 13 April by a vote of 204 to 59. Owing to the opposition of the Lords, and Pym's own preference for the more judicial method, the procedure of impeachment was adhered to. Few of the Lords felt much personal liking for Strafford, but there were a fair number of "moderates", notably Francis Russell, Earl of Bedford

Earl of Bedford is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England and is currently a subsidiary title of the Dukes of Bedford. The first creation came in 1138 in favour of Hugh de Beaumont. He appears to have been degraded fr ...

, who thought that barring him from ever serving the King again was sufficient punishment. The families of his first two wives, the Cliffords and Holleses, used all their influence to gain a reprieve: even Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles

Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles PC (31 October 1598 – 17 February 1680) was an English statesman, best remembered as one of the Five Members whose attempted arrest by Charles I in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War.

When fighti ...

, who was implacably hostile to the King, put aside political differences to plead for the life of his favourite sister's husband. Strafford might still have been saved but for Charles I's ill-advised conduct. A scheme to gain over the leaders of the parliament, and a scheme to seize the Tower of London and to liberate Strafford by force, were entertained concurrently and were mutually destructive. The revelation of the First Army Plot

The 1641 Army Plots were two separate alleged attempts by supporters of Charles I of England to use the army to crush the Parliamentary opposition in the run-up to the First English Civil War. The plan was to move the army from York to London and ...

on 5 May 1641 caused the Lords to reject the submissions in defence of Strafford by Richard Lane and to pass the attainder. Strafford's enemies were implacable in their determination that he should die: in the Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

's phrase "stone dead hath no fellow", while the view of Oliver St. John

Sir Oliver St John (; c. 1598 – 31 December 1673) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640-53. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil War.

Early life

St John was the son of Oliver St ...

was that Strafford should be regarded not a man, but as a dangerous animal who must be "knocked on the head". Nothing now remained but the King's signature.

Still, Strafford had served Charles with what the King felt was a high degree of loyalty, and Charles had a serious problem with signing Strafford's death warrant as a matter of conscience, especially as he had explicitly promised Stafford that, no matter what happened, he would not die. However, to refuse the will of the Parliament on this matter could seriously threaten the monarchy. When he summoned the bishops to ask for their advice, they were divided. Some, like James Ussher

James Ussher (or Usher; 4 January 1581 – 21 March 1656) was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, who today is most famous for his ident ...

, Archbishop of Armagh

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

argued that the King could not in conscience break his promise to Strafford to spare him; others, like Bishop John Williams

John Towner Williams (born February 8, 1932)Nylund, Rob (15 November 2022)Classic Connection review ''WBOI'' ("For the second time this year, the Fort Wayne Philharmonic honored American composer, conductor, and arranger John Williams, who wa ...

of Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

, took the contrary view that reasons of State permitted the King to break his word where a private citizen could not.

Charles had, after the passing of the attainder by the Commons, for the second time assured Strafford "upon the word of a king, you shall not suffer in life, honour or fortune". Strafford now wrote releasing the King from his engagements and declaring his willingness to die to reconcile Charles to his subjects. "I do most humbly beseech you, for the preventing of such massacres as may happen by your refusal, to pass the bill; by this means to remove ... the unfortunate thing forth of the way towards that blessed agreement, which God, I trust, shall for ever establish between you and your subjects". Whether Strafford was now resigned to death, or whether he thought that the letter, if circulated, might move his enemies to mercy, is still debated. The King did not release the letter to Parliament. Meanwhile, violent mobs threatened the palace with harm to the queen and her children. The King's inept efforts to overpower Parliament with military force were revealed by Pym and caused irresistible pressure. Charles gave his assent on 10 May, remarking sadly "My Lord Strafford's condition is happier than mine". Accounts of Strafford's reaction when he was told that he must die differ: by one account he took the news stoically; according to another he was deeply distressed, and said bitterly "Put not your trust in princes". Archbishop Laud wrote that the King's abandonment of Strafford proved him to be "a mild and gracious prince, that knows not how to be, or be made, great".

Death and aftermath

Strafford met his fate two days later on

Strafford met his fate two days later on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher grou ...

, receiving the blessing of Archbishop Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

(who went on to be likewise imprisoned in the Tower, and executed on 10 January 1645). He was executed before a crowd estimated, probably with some exaggeration, at 300,000 on 12 May 1641 (as this number was roughly the population of London at the time, the crowd is likely to have been a good deal smaller).

Following news of Strafford's execution, Ireland rose in sanguinary rebellion in October 1641, which led to more bickering between King and Parliament, this time over the raising of an army. Any hope that Strafford's death would avert the coming crisis soon vanished: Wedgwood quotes the anonymous protest "They promised us that all should be well if my Lord Strafford's head were off, since when there is nothing better". Many of Strafford's Irish enemies, like Lord Cork, found that his removal had put their estates, and even their lives, at risk. When Charles I himself was executed eight years later, among his last words were that God had permitted his execution as punishment for his consenting to Strafford's death: "that unjust sentence which I suffered to take effect". In 1660, the House of Lords voted to expunge the record of Strafford's attainder from its official Journal, with the intention of repudiating its legal validity.

Assessment

In the course of his career, he made many enemies, who pursued him, with a remarkable mixture of fear and hatred, to his death. Yet Strafford was capable of inspiring strong friendships in private life: at least three men who served him in Ireland,Christopher Wandesford

Christopher Wandesford (24 September 1592 – 3 December 1640) was an English administrator and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1621 and 1629. He was Lord Deputy of Ireland in the last months of his life.

Life

Wandesford was ...

, George Radcliffe and Guildford Slingsby

Guilford Slingsby (1610–1643) was a member of the Yorkshire gentry who was confidential secretary to Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, and present during the trial which ended in his execution in April 1641.

Slingsby sat in the Parlia ...

, remained his loyal friends to the end. Wentworth's last letter to Slingsby before his execution shows an emotional warmth with which he is not often credited.Wedgwood p.384 Sir Thomas Roe

Sir Thomas Roe ( 1581 – 6 November 1644) was an English diplomat of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. Roe's voyages ranged from Central America to India; as ambassador, he represented England in the Mughal Empire, the Ottoman Empire ...

speaks of him as "Severe abroad and in business, and sweet in private conversation; retired in his friendships but very firm; a terrible judge and a strong enemy". He was a good husband and a devoted father. His appearance is described by Sir Philip Warwick: "In his person he was of a tall stature, but stooped much in the neck. His countenance was cloudy whilst he moved or sat thinking, but when he spoke, either seriously or facetiously, he had a lightsome and a very pleasant air; and indeed whatever he then did he performed very gracefully". He himself jested on his own "bent and ill-favoured brow", Lord Exeter replying that had he been "cursed with a meek brow and an arch of white hair upon it, he would never have governed Ireland nor Yorkshire". Despite his terrifying manner, there is no real evidence that he was physically violent: even the most serious charge against him, that he ill-treated Robert Esmonde, causing his death, rests on disputed testimony.

Thomas was the subject of a verse play by the poet Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

entitled '' Strafford'' (1837).

Family

Strafford was married three times: * Margaret Clifford (died 1622), daughter ofFrancis Clifford, 4th Earl of Cumberland

Francis Clifford, 4th Earl of Cumberland (15594 January 1641) was a member of the Clifford family which held the seat of Skipton from 1310 to 1676.

He was the second son of Henry Clifford, 2nd Earl of Cumberland and Anne Dacre and inherited hi ...

.

* Arabella Holles (died October 1631), daughter of John Holles, 1st Earl of Clare

John Holles, 1st Earl of Clare (May 1564 – 4 October 1637) was an English nobleman.

He was the son of Denzil Holles of Irby upon Humber and Eleanor Sheffield (daughter of Edmund Sheffield, 1st Baron Sheffield of Butterwick). His great-grandfat ...

. Married in February 1625.

* Elizabeth Rhodes, daughter of Sir Godfrey Rhodes. Married in October 1632; she died in 1688.

Strafford's honours were forfeited by his attainder, but his only son, William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, who was born on 8 June 1626, received them all by a fresh grant from Charles I on 1 December 1641. In 1662 Parliament reversed his father's attainder, and William, already 1st Earl of Strafford of the second creation, became also 2nd earl of the first creation in succession to his father.

In addition to William, Strafford and Arabella had two daughters who outlived him: Anne, born October 1627, who married Edward Watson, 2nd Baron Rockingham

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

; and Arabella, born October 1630, who married Justin McCarthy, Viscount Mountcashel

Justin McCarthy, 1st Viscount Mountcashel, PC (Ire) ( – 1694), was a Jacobite general in the Williamite War in Ireland and a personal friend of James II. He commanded Irish Army troops during the conflict, enjoying initial success wh ...

. Through his daughter Anne, Strafford was the ancestor of the prominent eighteenth-century statesman Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, (13 May 1730 – 1 July 1782; styled The Hon. Charles Watson-Wentworth before 1733, Viscount Higham between 1733 and 1746, Earl of Malton between 1746 and 1750 and The Marquess of Rocking ...

. Strafford had a daughter, Margaret, with his third wife. The hatred felt by so many for Strafford did not extend to his widow and children, who were generally regarded with compassion: even at the height of the Civil War Parliament treated "that poor unfortunate family" with consideration.

Film portrayals

Strafford was portrayed byPatrick Wymark

Patrick Wymark (11 July 192620 October 1970) was an English stage, film and television actor.

Early life

Wymark was born Patrick Carl Cheeseman in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire. He was brought up in neighbouring Grimsby and frequently revisited th ...

in the historical drama film ''Cromwell'' (1970).

Ancestry

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * a much more hostile perspective than her first edition * * Attribution: *Further reading

* Cooper, J. P. "The Fortune of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford." ''Economic History Review'' 11#2 1958, pp. 227–248online

* Cooper, Elizabeth, ''The Life of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford'' (2 vol 1874

online

* * Orr, D. Alan. '' Treason and the State'' (2002): pp 61–100 on Wentworth

online

* Wedgwood, C. V. "The lost archangel a new view of Strafford" ''History Today'' (1951) 1#1 pp 18–24 online.

External links

** ttp://www.york.ac.uk/univ/coll/went Wentworth Graduate College of the University of York, named in honor of Thomas Wentworth* *

Portrait of the Earl of Strafford in the UK Parliamentary Collections

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Strafford, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl Of 1593 births 1641 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Members of the Inner Temple English soldiers English Anglicans People convicted under a bill of attainder Executions at the Tower of London Knights of the Garter Lord-Lieutenants of Yorkshire Lords Lieutenant of Ireland Executed military leaders Executed people from London People executed by Stuart England by decapitation High Sheriffs of Yorkshire English MPs 1614 English MPs 1621–1622 English MPs 1624–1625 English MPs 1625 English MPs 1628–1629 English politicians convicted of crimes Earls of Strafford (1640 creation)