Sir Rowland Hill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Rowland Hill, KCB, FRS (3 December 1795 ŌĆō 27 August 1879) was an English teacher, inventor and

The colonisation of South Australia was a project of

The colonisation of South Australia was a project of

In the 1830s at least 12.5% of all British mail was conveyed under the personal

In the 1830s at least 12.5% of all British mail was conveyed under the personal  Hill's pamphlet, ''Post Office Reform: its Importance and Practicability'', referred to above, was circulated privately in 1837. The report called for "low and uniform rates" according to weight, rather than distance. Hill's study reported his findings and those of Charles Babbage that most of the costs in the postal system were not for transport, but rather for laborious handling procedures at the origins and the destinations. Costs could be reduced dramatically if postage were prepaid by the sender, the prepayment to be proven by the use of prepaid letter sheets or adhesive stamps (adhesive stamps had long been used to show payment of taxes, on documents for example).

Hill's pamphlet, ''Post Office Reform: its Importance and Practicability'', referred to above, was circulated privately in 1837. The report called for "low and uniform rates" according to weight, rather than distance. Hill's study reported his findings and those of Charles Babbage that most of the costs in the postal system were not for transport, but rather for laborious handling procedures at the origins and the destinations. Costs could be reduced dramatically if postage were prepaid by the sender, the prepayment to be proven by the use of prepaid letter sheets or adhesive stamps (adhesive stamps had long been used to show payment of taxes, on documents for example).  In the House of Lords the Postmaster,

In the House of Lords the Postmaster,

Rowland Hill continued at the Post Office until the

Rowland Hill continued at the Post Office until the

/ref>

Hill has two legacies. The first was his model for education of the emerging middle classes. The second was his model for an efficient

Hill has two legacies. The first was his model for education of the emerging middle classes. The second was his model for an efficient  There are at least two marble busts of Hill, also unveiled in 1881. One, by W. D. Keyworth, Jr., is in St Paul's Chapel,

There are at least two marble busts of Hill, also unveiled in 1881. One, by W. D. Keyworth, Jr., is in St Paul's Chapel,

volume 1volume 2

* * * * * (Eleanor Smyth was Hill's daughter.)

Sir Rowland Hill at National Portrait Gallery, London (npg.org.uk)

* * * (Extract from Smyth's ''Sir Rowland Hill; the story of a great reform'') * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hill, Rowland (postal reformer) 1795 births 1879 deaths 18th-century English people 19th-century English people Burials at Westminster Abbey Burials at Highgate Cemetery English inventors Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Kidderminster Postal history Postal pioneers American Philatelic Society Committee members of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

. He campaigned for a comprehensive reform of the postal system

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal syst ...

, based on the concept of Uniform Penny Post

The Uniform Penny Post was a component of the comprehensive reform of the Royal Mail, the UK's official postal service, that took place in the 19th century. The reforms were a government initiative to eradicate the abuse and corruption of the e ...

and his solution of pre-payment, facilitating the safe, speedy and cheap transfer of letters. Hill later served as a government postal official, and he is usually credited with originating the basic concepts of the modern postal service, including the invention of the postage stamp.

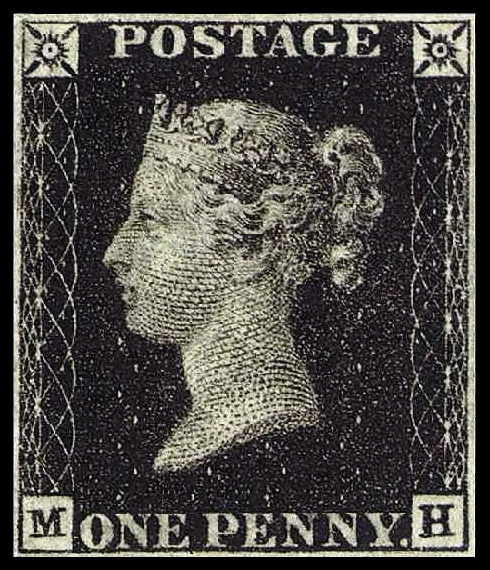

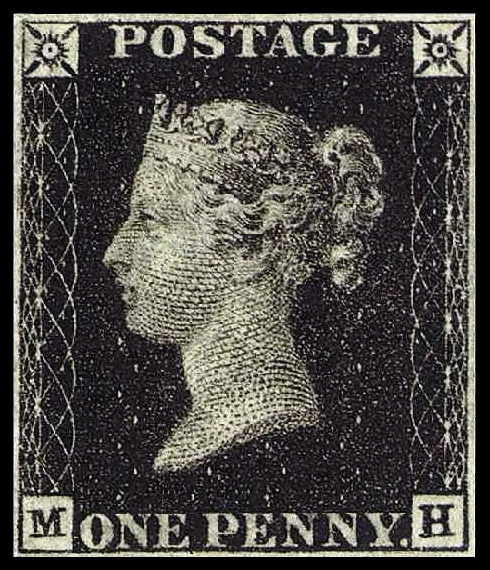

Hill made the case that if letters were cheaper to send, people, including the poorer classes, would send more of them, thus eventually profits would go up. Proposing an adhesive stamp to indicate pre-payment of postage ŌĆō with the first being the Penny Black ŌĆō in 1840, the first year of Penny Post, the number of letters sent in the UK more than doubled. Within 10 years, it had doubled again. Within three years postage stamps were introduced in Switzerland and Brazil, a little later in the US, and by 1860, they were used in 90 countries.

Personal life

Hill was born in Blackwell Street,Kidderminster

Kidderminster is a large market and historic minster town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, south-west of Birmingham and north of Worcester. Located north of the River Stour and east of the River Severn, in the 2011 census, it ha ...

, Worcestershire, England. Rowland's father, Thomas Wright Hill, was an innovator in education and politics, including among his friends Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 ŌĆō 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

, Tom Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; ŌĆō In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736ŌĆō37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

and Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 ŌĆō 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

. At the age of 12, Rowland became a student-teacher in his father's school. He taught astronomy and earned extra money fixing scientific instruments. He also worked at the Assay Office in Birmingham and painted landscapes in his spare time.

In 1827 he married Caroline Pearson, originally from Wolverhampton, who died on 27 May 1881. Together they had four children, daughters Eleanor, Clara and Louisa and a son Pearson.

Educational reform

In 1819 he moved his father's school "Hill Top" from central Birmingham, establishing the Hazelwood School atEdgbaston

Edgbaston () is an affluent suburban area of central Birmingham, England, historically in Warwickshire, and curved around the southwest of the city centre.

In the 19th century, the area was under the control of the Gough-Calthorpe family a ...

, an affluent neighbourhood of Birmingham, as an "educational refraction of Priestley's ideas". Hazelwood was to provide a model for public education for the emerging middle classes, aiming for useful, pupil-centred education which would give sufficient knowledge, skills and understanding to allow a student to continue self-education through a life "most useful to society and most happy to himself". The school, which Hill designed, included innovations such as a science laboratory, a swimming pool, and forced air heating. In his ''Plans for the Government and Liberal Instruction of Boys in Large Numbers Drawn from Experience'' (1822, often cited as ''Public Education'') he argued that kindness, instead of caning, and moral influence, rather than fear, should be the predominant forces in school discipline. Science was to be a compulsory subject, and students were to be self-governing.

Hazelwood gained international attention when French education leader and editor Marc Antoine Jullien, former secretary to Maximilien de Robespierre

Maximilien Fran├¦ois Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 ŌĆō 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

, visited and wrote about the school in the June 1823 issue of his journal ''Revue encyclop├®dique''. Jullien even transferred his son there. Hazelwood so impressed Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

that in 1827 a branch of the school was created at Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle (formerly the Lordship House) is a Grade I listed 16th-century manor house in Lordship Lane, Tottenham, London. It is named after the House of Bruce who formerly owned the land on which it is built. Believed to stand on the site ...

in Tottenham

Tottenham () is a town in North London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, bordering Edmonton to the north, Wal ...

, London. In 1833, the original Hazelwood School closed and its educational system was continued at the new Bruce Castle School

Bruce Castle School, at Bruce Castle, Tottenham, was a progressive school for boys established in 1827 as an extension of Rowland Hill's Hazelwood School at Edgbaston. It closed in 1891.

Origins

In 1819, Rowland Hill moved his father's Hill To ...

, of which Hill was head master from 1827 until 1839.

Colonisation of South Australia

The colonisation of South Australia was a project of

The colonisation of South Australia was a project of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield (20 March 179616 May 1862) is considered a key figure in the establishment of the colonies of South Australia and New Zealand (where he later served as a member of parliament). He also had significant interests in Brit ...

, who believed that many of the social problems in Britain were caused by overcrowding and overpopulation. In 1832 Rowland Hill published a tract called ''Home colonies: sketch of a plan for the gradual extinction of pauperism, and for the diminution of crime'', based on a Dutch model. Hill then served from 1833 until 1839 as secretary of the South Australian Colonization Commission

British colonisation of South Australia describes the planning and establishment of the colony of South Australia by the British government, covering the period from 1829, when the idea was raised by the then-imprisoned Edward Gibbon Wakefield ...

, which worked successfully to establish a settlement without convicts at what is today Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. The political economist Robert Torrens was chairman of the Commission. Under the South Australia Act 1834

The ''South Australia Act 1834'', or ''Foundation Act 1834'' and also known as the ''South Australian Colonization Act'', was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the settlement of a province or multiple province ...

, the colony was to embody the ideals and best qualities of British society, shaped by religious freedom

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

and a commitment to social progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension wi ...

and civil liberties.

Hill was an advocate for proportional representation. Adelaide was one of the first places in the world to use the "British form of pro-rep" Single transferable voting

Single transferable vote (STV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which voters cast a single vote in the form of a ranked-choice ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternate p ...

in the mid-1800s.

Rowland Hill's sister Caroline Clark, her husband Francis and their large family migrated to South Australia in 1850.

Postal reform

Rowland Hill first started to take a serious interest in postal reforms in 1835. In 1836 Robert Wallace, MP, provided Hill with numerous books and documents, which Hill described as a "half hundred weight of material". Hill commenced a detailed study of these documents and this led him to publish, in early 1837, a pamphlet called ''Post Office Reform its Importance and Practicability''. He submitted a copy of this to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Thomas Spring Rice, on 4 January 1837. This first edition was marked "private and confidential" and was not released to the general public. The Chancellor summoned Hill to a meeting in which the Chancellor suggested improvements, asked for reconsiderations and requested a supplement, which Hill duly produced and supplied on 28 January 1837.frank

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curr ...

of peers, dignitaries and members of parliament, while censorship and political espionage were conducted by postal officials. Fundamentally, the postal system was mismanaged, wasteful, expensive and slow. It had become inadequate for the needs of an expanding commercial and industrial nation. There is a well-known story, probably apocryphal, about how Hill gained an interest in reforming the postal system; he apparently noticed a young woman too poor to claim a letter sent to her by her fianc├®. At that time, letters were normally paid for by the recipient, not the sender. The recipient could simply refuse delivery. Frauds were commonplace: for example, coded information could appear on the cover of the letter; the recipient would examine the cover to gain the information, and then refuse delivery to avoid payment. Each individual letter had to be logged. In addition, postal rates were complex, depending on the distance and the number of sheets in the letter.

Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 ŌĆō 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the CobdenŌĆōChevalier Treaty.

As a you ...

and John Ramsey McCulloch, both advocates of free trade, attacked the policies of privilege and protection of the Tory government. McCulloch, in 1833, advanced the view that "nothing contributes more to facilitate commerce than the safe, speedy and cheap conveyance of letters."

Letter sheet

In philatelic terminology a letter sheet, often written lettersheet, is a sheet of paper that can be folded, usually sealed (most often with sealing wax in the 18th and 19th centuries), and mailed without the use of an envelope, or it can also ...

s were to be used because envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter or card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one of three shapes: a rhombus, a sh ...

s were not yet common; they were not yet mass-produced, and in an era when postage was calculated partly on the basis of the number of sheets of paper used, the same sheet of paper would be folded and serve for both the message and the address. In addition, Hill proposed to lower the postage rate to a penny per half ounce, without regard to distance. He first presented his proposal to the government in 1837.

In the House of Lords the Postmaster,

In the House of Lords the Postmaster, Lord Lichfield

Earl of Lichfield is a title that has been created three times, twice in the Peerage of England (1645 and 1674) and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom (1831). The third creation is extant and is held by a member of the Anson family.

Hi ...

, a Whig, denounced Hill's "wild and visionary schemes." William Leader Maberly, Secretary to the Post Office, also a Whig, denounced Hill's study: "This plan appears to be a preposterous one, utterly unsupported by facts and resting entirely on assumption". But merchants, traders and bankers viewed the existing system as corrupt and a restraint of trade. They formed a "Mercantile Committee" to advocate Hill's plan and push for its adoption. In 1839 Hill was given a two-year contract to run the new system.

From 1839 to 1842, Hill lived at 1 Orme Square, Bayswater, London, and there is an LCC plaque there in his honour.

The uniform fourpenny post rate lowered the cost to fourpence from 5 December 1839, then to the penny rate on 10 January 1840, even before stamps or letter sheets could be printed. The volume of paid internal correspondence increased dramatically, by 120%, between November 1839 and February 1840. This initial increase resulted from the elimination of "free franking" privileges and fraud.

Prepaid letter sheets, with a design by William Mulready

William Mulready (1 April 1786 ŌĆō 7 July 1863) was an Irish genre painter living in London. He is best known for his romanticising depictions of rural scenes, and for creating Mulready stationery letter sheets, issued at the same time as the P ...

, were distributed in early 1840. These Mulready envelopes were not popular and were widely satirised. According to a brochure distributed by the National Postal Museum (now the British Postal Museum & Archive), the Mulready envelopes threatened the livelihoods of stationery manufacturers, who encouraged the satires. They became so unpopular that the government used them on official mail and destroyed many others.

However, a niche commercial publishing industry for machine-printed illustrated envelopes subsequently developed in Britain and elsewhere. So it is likely that it was the grandiose and incomprehensible illustration printed on the envelopes that provoked the ridicule and led to their withdrawal. Indeed, in the absence of examples of machine-printed illustrated envelopes before this, the Mulready envelope may be recognised as a significant innovation in its own right. Machine-printed illustrated envelopes are a mainstay of the direct mail

Advertising mail, also known as direct mail (by its senders), junk mail (by its recipients), mailshot or admail (North America), letterbox drop or letterboxing (Australia) is the delivery of advertising material to recipients of postal mail. The d ...

industry.

In May 1840 the world's first adhesive postage stamps were distributed. With an elegant engraving of the young Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 ŌĆō 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

(whose 21st birthday was celebrated that month), the Penny Black was an instant success. Refinements, such as perforations to ease the separation of the stamps, were instituted with later issues.

Later life

Rowland Hill continued at the Post Office until the

Rowland Hill continued at the Post Office until the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

won the 1841 General Election. Sir Robert Peel returned to office on 30 August 1841 and served until 29 June 1846. Amid rancorous controversy, Hill was dismissed in July 1842. However, the London and Brighton Railway

The London and Brighton Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in England which was incorporated in 1837 and survived until 1846. Its railway ran from a junction with the London and Croydon Railway (L&CR) at Norwood ŌĆō which gives it access fro ...

named him a director and later chairman of the board, from 1843 to 1846. He lowered the fares from London to Brighton, expanded the routes, offered special excursion trains, and made the commute comfortable for passengers. In 1844 Edwin Chadwick, Rowland Hill, John Stuart Mill, Lyon Playfair

Lyon Playfair, 1st Baron Playfair (1 May 1818 ŌĆō 29 May 1898) was a British scientist and Liberal politician who was Postmaster-General from 1873 to 1874.

Early life

Playfair was born at Chunar, Bengal, the son of George Playfair (1782-1846 ...

, Dr. Neil Arnott

Dr Neil Arnott FRS LLD (15 May 1788March 1874) was a Scottish physician and inventor. He was the inventor of one of the first forms of the waterbed, the Arnott waterbed, and was awarded the Rumford Medal in 1852 for the construction of th ...

, and other friends formed a society called "Friends in Council," which met at each other's houses to discuss questions of political economy. Hill also became a member of the influential Political Economy Club, founded by David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 ŌĆō 11 September 1823) was a British political economist. He was one of the most influential of the classical economists along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill. Ricardo was also a politician, and a ...

and other classical economists, but now including many powerful businessmen and political figures. Mill and Hill were both advocates for proportional representation.

In 1846 the Conservative party split over the repeal of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

and was replaced by a Whig government In British politics, a Whig government may refer to the following British governments administered by the Whigs:

* Whig Junto, a name given to a group of leading Whigs who were seen to direct the management of the Whig Party

**First Whig Junto, th ...

led by Lord Russell. Hill was made Secretary to the Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

, and then Secretary to the Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional ser ...

from 1854 until 1864. For his services Hill was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as o ...

in 1860. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

and awarded an honorary degree from University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = ┬Ż6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = ┬Ż2.145 billion (2019ŌĆō20)

, chancellor ...

.

For the last 30 years of his life, and where he died in 1879, Hill lived at Bartram House on Hampstead Green. Bartrams, was the largest house in a row of four Georgian mansions which were demolished at the start of the twentieth century to make way for Hampstead General Hospital, which was itself demolished in the 1970s and replaced by The Royal Free Hospital

The Royal Free Hospital (also known simply as the Royal Free) is a major teaching hospital in the Hampstead area of the London Borough of Camden. The hospital is part of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, which also runs services at Bar ...

. For twenty years his next-door neighbour on Hampstead Green was the gothic revival architect Samuel Sanders Teulon

Samuel Sanders Teulon (2 March 1812 ŌĆō 2 May 1873) was an English Gothic Revival architect, noted for his use of polychrome brickwork and the complex planning of his buildings.

Family

Teulon was born in 1812 in Greenwich, Kent, the son of a ...

who designed St Stephen's Church, Rosslyn Hill facing their houses. He is buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

; there is a memorial to him on his family grave in Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in north London, England. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East Cemeteries. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for some of the people buried there as ...

. There are streets named after him in Hampstead (off Haverstock Hill, down the side of the Royal Free Hospital) and Tottenham (off White Hart Lane

White Hart Lane was a football stadium in Tottenham, North London and the home of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club from 1899 to 2017. Its capacity varied over the years; when changed to all-seater it had a capacity of 36,284 before demolition. ...

). A Royal Society of Arts blue plaque, unveiled in 1893, commemorates Hill at the Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead.

Family

Hill was one of eight children. One brother,Matthew Davenport Hill

Matthew Davenport Hill (6 August 1792 ŌĆō 7 June 1872) was an English lawyer and prison reform campaigner and MP.

Life

Hill was born at Birmingham, where his father, Thomas Wright Hill, for long conducted the private schools Hazelwood and Bruce ...

(1792ŌĆō1872), was Recorder of Birmingham, a campaigner on prison reform

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of a penal system, or implement alternatives to incarceration. It also focuses on ensuring the reinstatement of those whose lives are impacted by crimes ...

, and, from 1832, MP for Hull.

Another was Edwin Hill (1793ŌĆō1876), who was the first British Controller of Stamps

Controller may refer to:

Occupations

* Controller or financial controller, or in government accounting comptroller, a senior accounting position

* Controller, someone who performs agent handling in espionage

* Air traffic controller, a person ...

from 1840 until 1872, and invented a mechanical system to make envelopes.I.D. Hill, "Hill, Edwin (1793ŌĆō1876)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2009. Yet another was the prison inspector Frederic Hill (1803ŌĆō1896).Deborah Sara Gorham, ŌĆśHill, Rosamond Davenport (1825ŌĆō1902)ŌĆÖ, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200/ref>

Legacy and commemorations

Hill has two legacies. The first was his model for education of the emerging middle classes. The second was his model for an efficient

Hill has two legacies. The first was his model for education of the emerging middle classes. The second was his model for an efficient postal system

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal syst ...

to serve business and the public, including the postage stamp and the system of low and uniform postal rates, which is often taken for granted in the modern world. In this, he not only changed postal services around the world, but also made commerce more efficient and profitable, even though it took 30 years before the British Post Office's revenue recovered to its 1839 level. The Uniform Penny Post continued in the UK into the 20th century, and at one point, one penny (1d) paid for up to four ounces (113 g).

There are four public statues of Hill. The earliest is in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

: a Carrara marble

Carrara marble, Luna marble to the Romans, is a type of white or blue-grey marble popular for use in sculpture and building decor. It has been quarried since Roman times in the mountains just outside the city of Carrara in the province of Massa ...

sculpture by Peter Hollins unveiled in 1870. Its location was moved in 1874, 1891 (when it was placed in the City's General Post Office) and 1934. In 1940 it was removed for safe keeping for the duration of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposi ...

. It is now in the foyer of the Royal Mail sorting office in Newtown, Birmingham.

A marble statue in Kidderminster, Hill's birthplace, was sculpted by Sir Thomas Brock

Sir Thomas Brock (1 March 184722 August 1922) was an English sculptor and medallist, notable for the creation of several large public sculptures and monuments in Britain and abroad in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

His mos ...

and unveiled in June 1881. It is at the junction of Vicar and Exchange Streets. Hill is prominent in Kidderminster's community history. There used to be a J D Wetherspoon

J D Wetherspoon plc (branded variously as Wetherspoon or Wetherspoons, and colloquially known as Spoons) is a pub company operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The company was founded in 1979 by Tim Martin and is based in Watford. It o ...

pub called The Penny Black in the town centre until 2019 and a large shopping mall linking Vicar Street and Worcester Street is named The Rowland Hill Shopping Centre.

In London a bronze statue by Edward Onslow Ford, also made in 1881, stands in King Edward Street. There is a large sculpture in Dalton Square, Lancaster, The Victoria Monument, depicting eminent Victorians and Rowland Hill is included.

There are at least two marble busts of Hill, also unveiled in 1881. One, by W. D. Keyworth, Jr., is in St Paul's Chapel,

There are at least two marble busts of Hill, also unveiled in 1881. One, by W. D. Keyworth, Jr., is in St Paul's Chapel, Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

. Another, by William Theed

William Theed, also known as William Theed the younger (1804 ŌĆō 9 September 1891), was a British sculptor, the son of the sculptor and painter William Theed the elder (1764ŌĆō1817). Although versatile and eclectic in his works, he specialised ...

, is in Albert Square

Walford is a fictional borough of east London in the BBC soap opera '' EastEnders''. It is the primary setting for the soap. ''EastEnders'' is filmed at Borehamwood in Hertfordshire, towards the north-west of London. Much of the location ...

, Manchester.

In recognition of his contributions to the development of the modern postal system, Rowland Hill is commemorated at the Universal Postal Union

The Universal Postal Union (UPU, french: link=no, Union postale universelle), established by the Treaty of Bern of 1874, is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) that coordinates postal policies among member nations, in addition to ...

, the UN agency charged with regulating the international postal system. His name appears on one of the two large meeting halls at the UPU headquarters in Bern, Switzerland.

At Tottenham

Tottenham () is a town in North London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, bordering Edmonton to the north, Wal ...

, north London, there is a local history museum at Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle (formerly the Lordship House) is a Grade I listed 16th-century manor house in Lordship Lane, Tottenham, London. It is named after the House of Bruce who formerly owned the land on which it is built. Believed to stand on the site ...

(where Hill lived during the 1840s) including some relevant exhibits.

In Adelaide, capital of South Australia, both Hill Street, North Adelaide and Rowland Place in the city centre are named in his honour.

The Rowland Hill Awards, started by the Royal Mail and the British Philatelic Trust

The British Philatelic Trust was established in 1981 by the British Post Office. The governing deed was executed on 26 September 1983.Department of Posts and Telegraphs

The Minister for Posts and Telegraphs ( ga, Aire Poist agus Telegrafa) was the holder of a position in the Government of Ireland (and, earlier, in the Executive Council of the Irish Free State). From 1924 until 1984 ŌĆō when it was abolished ŌĆ ...

and continues to serve the reorganised companies An Post and eircom. The fund assists more than 300 people annually.

Philatelic commemorations

For the centenary of the first stamp, Portugal issued a miniature sheet with 8 stamps mentioning his name. Later, on his death centenary, an omnibus issue of stamps commemorating Hill was produced by about 80 countries. Altogether, 147 countries have issued stamps commemorating him.See also

*Penny Blue

{{Infobox rare stamps

, common_name = Penny Blue

, image = Onepennyblue.jpg

, country_of_production = United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

, location_of_production = London

, date_of_producti ...

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *volume 1

* * * * * (Eleanor Smyth was Hill's daughter.)

External links

Sir Rowland Hill at National Portrait Gallery, London (npg.org.uk)

* * * (Extract from Smyth's ''Sir Rowland Hill; the story of a great reform'') * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hill, Rowland (postal reformer) 1795 births 1879 deaths 18th-century English people 19th-century English people Burials at Westminster Abbey Burials at Highgate Cemetery English inventors Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Kidderminster Postal history Postal pioneers American Philatelic Society Committee members of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge