Sir Roger Penrose on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English

In 1967, Penrose invented the

In 1967, Penrose invented the

In 2010, Penrose reported possible evidence, based on concentric circles found in Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data of the

In 2010, Penrose reported possible evidence, based on concentric circles found in Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data of the

Penrose has written books on the connection between fundamental physics and human (or animal) consciousness. In ''

Penrose has written books on the connection between fundamental physics and human (or animal) consciousness. In '' Finally, he suggested that the configuration of the microtubule lattice might be suitable for quantum error correction, a means of holding together quantum coherence in the face of environmental interaction.

Hameroff, in a lecture in part of a Google Tech talks series exploring quantum biology, gave an overview of current research in the area, and responded to subsequent criticisms of the Orch-OR model. In addition to this, a 2011 paper by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff published in the ''Journal of Cosmology'' gives an updated model of their Orch-OR theory, in light of criticisms, and discusses the place of consciousness within the universe.

Phillip Tetlow, although himself supportive of Penrose's views, acknowledges that Penrose's ideas about the human thought process are at present a minority view in scientific circles, citing Minsky's criticisms and quoting science journalist Charles Seife's description of Penrose as "one of a handful of scientists" who believe that the nature of consciousness suggests a quantum process.

In January 2014, Hameroff and Penrose ventured that a discovery of quantum vibrations in microtubules by Anirban Bandyopadhyay of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan supports the hypothesis of Orchestrated objective reduction, Orch-OR theory. A reviewed and updated version of the theory was published along with critical commentary and debate in the March 2014 issue of ''Physics of Life Reviews''.

Finally, he suggested that the configuration of the microtubule lattice might be suitable for quantum error correction, a means of holding together quantum coherence in the face of environmental interaction.

Hameroff, in a lecture in part of a Google Tech talks series exploring quantum biology, gave an overview of current research in the area, and responded to subsequent criticisms of the Orch-OR model. In addition to this, a 2011 paper by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff published in the ''Journal of Cosmology'' gives an updated model of their Orch-OR theory, in light of criticisms, and discusses the place of consciousness within the universe.

Phillip Tetlow, although himself supportive of Penrose's views, acknowledges that Penrose's ideas about the human thought process are at present a minority view in scientific circles, citing Minsky's criticisms and quoting science journalist Charles Seife's description of Penrose as "one of a handful of scientists" who believe that the nature of consciousness suggests a quantum process.

In January 2014, Hameroff and Penrose ventured that a discovery of quantum vibrations in microtubules by Anirban Bandyopadhyay of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan supports the hypothesis of Orchestrated objective reduction, Orch-OR theory. A reviewed and updated version of the theory was published along with critical commentary and debate in the March 2014 issue of ''Physics of Life Reviews''.

“The Map and the Territory: Exploring the foundations of science, thought and reality”

by Shyam Wuppuluri and Francisco Antonio Doria. Published by Springer in "The Frontiers Collection", 2018. * Foreword t

''Beating the Odds: The Life and Times of E. A. Milne''

written by Meg Weston Smith. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co in June 2013. * Foreword t

"A Computable Universe"

by Hector Zenil. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co in December 2012. * Foreword to ''Quantum Aspects of Life'' by Derek Abbott, Paul C. W. Davies, and Arun K. Pati. Published by Imperial College Press in 2008. * Foreword t

''Fearful Symmetry''

by Anthony Zee's. Published by Princeton University Press in 2007.

Penrose has been awarded many prizes for his contributions to science.

In 1971, he was awarded the Dannie Heineman Prize for Astrophysics. He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1972, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1972. In 1975, Stephen Hawking and Penrose were jointly awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1985, he was awarded the Royal Society Royal Medal. Along with Stephen Hawking, he was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics, Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics in 1988.

In 1989, Penrose was awarded the Dirac Prize, Dirac Medal and Prize of the British Institute of Physics. He is also made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics (HonFInstP).

In 1990, Penrose was awarded the Albert Einstein Medal for outstanding work related to the work of Albert Einstein by the Albert Einstein Society. In 1991, he was awarded the Naylor Prize of the London Mathematical Society. From 1992 to 1995, he served as President of th

Penrose has been awarded many prizes for his contributions to science.

In 1971, he was awarded the Dannie Heineman Prize for Astrophysics. He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1972, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1972. In 1975, Stephen Hawking and Penrose were jointly awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1985, he was awarded the Royal Society Royal Medal. Along with Stephen Hawking, he was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics, Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics in 1988.

In 1989, Penrose was awarded the Dirac Prize, Dirac Medal and Prize of the British Institute of Physics. He is also made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics (HonFInstP).

In 1990, Penrose was awarded the Albert Einstein Medal for outstanding work related to the work of Albert Einstein by the Albert Einstein Society. In 1991, he was awarded the Naylor Prize of the London Mathematical Society. From 1992 to 1995, he served as President of th

International Society on General Relativity and Gravitation

In 1994, Penrose was Knight Bachelor, knighted for services to science. In the same year, he was also awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) by the University of Bath, and became a member of Polish Academy of Sciences. In 1998, he was elected Foreign Associate of the United States National Academy of Sciences. In 2000, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Merit (OM). In 2004, he was awarded the De Morgan Medal for his wide and original contributions to mathematical physics. To quote the citation from the London Mathematical Society: In 2005, Penrose was awarded an Honorary degree, honorary doctorate by Warsaw University and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium), and in 2006 by the University of York. In 2006, he also won the Dirac Medal given by the University of New South Wales. In 2008, Penrose was awarded the Copley Medal. He is also a Distinguished Supporter of Humanists UK and one of the patrons of the Oxford University Scientific Society. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2011. The same year, he was also awarded the Fonseca Prize by the University of Santiago de Compostela. In 2012, Penrose was awarded the Richard R. Ernst Medal by ETH Zürich for his contributions to science and strengthening the connection between science and society. In 2015 Penrose was awarded an honorary doctorate by CINVESTAV, CINVESTAV-IPN (Mexico). In 2017, he was awarded the Commandino Medal at the Urbino University for his contributions to the history of science. In 2020, Penrose was awarded one half of the

Awake in the Universe

– Penrose debates how creativity, the most elusive of faculties, has helped us unlock the country of the mind and the mysteries of the cosmos with Bonnie Greer. * * – Penrose was one of the principal interviewees in a BBC documentary about the mathematics of infinity directed by David Malone (independent filmmaker), David Malone * Penrose's new theory "Aeons Before the Big Bang?": ** Original 2005 lecture

"Before the Big Bang? A new perspective on the Weyl curvature hypothesis"

(Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge, 11 November 2005). ** Original publication

"Before the Big Bang: an outrageous new perspective and its implications for particle physics".

''Proceedings of EPAC 2006''. Edinburgh. 2759–2762 (cf. also Hill, C.D. & Nurowski, P. (2007

"On Penrose's 'Before the Big Bang' ideas"

Ithaca) ** Revised 2009 lecture

"Aeons Before the Big Bang?"

(Georgia Institute of Technology, Center for Relativistic Astrophysics) **

Roger Penrose

on ''The Forum (BBC World Service), The Forum'' *

Hilary Putnam's review of Penrose's 'Shadows of the Mind' claiming that Penrose's use of Godel's Incompleteness Theorem is fallacious

**

Penrose Tiling found in Islamic Architecture

* ** "[https://web.archive.org/web/20051024022835/http://www.quantumconsciousness.org/pdfs/decoherence.pdf Biological feasibility of quantum states in the brain]" – (a disputation of Tegmark's result by Hagan, Hameroff, and Tuszyński) **

Tegmarks's rejoinder to Hagan ''et al.''

* – D. Trull about Penrose's lawsuit concerning the use of his Penrose tilings on toilet paper

(''Plus Magazine'')

Penrose's Gifford Lecture biography

Quantum-Mind

Audio: Roger Penrose in conversation on the BBC World Service discussion show

Roger Penrose speaking about Hawking's new book on Premier Christian Radio

"The Cyclic Universe – A conversation with Roger Penrose"

''Ideas Roadshow'', 2013

Forbidden crystal symmetry in mathematics and architecture

filmed event at the Royal Institution, October 2013

''Oxford Mathematics Interviews'': "Extra Time: Professor Sir Roger Penrose in conversation

with

BBC Radio 4 – The Life Scientific – Roger Penrose on Black Holes – 22 November 2016

Sir Roger Penrose talks to Jim Al-Khalili about his trailblazing work on how black holes form, the problems with quantum physics and his portrayal in films about Stephen Hawking.

The Penrose Institute

Website

A chess problem holds the key to human consciousness?

Chessbase * {{DEFAULTSORT:Penrose, Roger 1931 births Living people People from Colchester 20th-century British mathematicians Mathematics popularizers 20th-century British philosophers 20th-century British physicists 21st-century British mathematicians 21st-century British philosophers 21st-century British physicists Academics of Birkbeck, University of London Academics of King's College London Albert Einstein Medal recipients Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of London Alumni of University College London British expatriate academics in the United States British Nobel laureates British consciousness researchers and theorists English agnostics English humanists English expatriates in the United States British geometers English people of Russian-Jewish descent English science writers Recreational mathematicians Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford Knights Bachelor Mathematical physicists Members of the Order of Merit Nobel laureates in Physics Pennsylvania State University faculty People educated at University College School Philosophers of science Professors of Gresham College Quantum mind Quantum physicists Recipients of the Copley Medal British relativity theorists Rice University faculty Rouse Ball Professors of Mathematics (University of Oxford) Royal Medal winners Wolf Prize in Physics laureates English people of Irish descent Recipients of the Dalton Medal

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, mathematical physicist

Mathematical physics refers to the development of mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The ''Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the developmen ...

, philosopher of science

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and Nobel Laureate in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

. He is Emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics

The Rouse Ball Professorship of Mathematics is one of the senior chairs in the Mathematics Departments at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford. The two positions were founded in 1927 by a bequest from the mathematician W. W. Ro ...

in the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, an emeritus fellow of Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy W ...

, and an honorary fellow of St John's College, Cambridge and University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

.

Penrose has contributed to the mathematical physics of general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

and cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount (lexicographer), Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in ...

. He has received several prizes and awards, including the 1988 Wolf Prize in Physics

The Wolf Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Wolf Foundation in Israel. It is one of the six Wolf Prizes established by the Foundation and awarded since 1978; the others are in Agriculture, Chemistry, Mathematics, Medicine and Arts.

...

, which he shared with Stephen Hawking for the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems

The Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems (after Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking) are a set of results in general relativity that attempt to answer the question of when gravitation produces singularities. The Penrose singularity theorem is ...

, and one half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

"for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity". He is regarded as one of the greatest living physicists, mathematicians and scientists, and is particularly noted for the breadth and depth of his work in both natural and formal sciences.

Early life and education

Born inColchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

, Essex, Roger Penrose is a son of medical doctor Margaret (Leathes) and psychiatrist and geneticist Lionel Penrose

Lionel Sharples Penrose, FRS (11 June 1898 – 12 May 1972) was an English psychiatrist, medical geneticist, paediatrician, mathematician and chess theorist, who carried out pioneering work on the genetics of intellectual disability. Penrose ...

. His paternal grandparents were J. Doyle Penrose, an Irish-born artist, and The Hon. Elizabeth Josephine, daughter of Alexander Peckover, 1st Baron Peckover

Alexander Peckover, 1st Baron Peckover LL FRGS, FSA, FLS (16 August 1830 – 21 October 1919), was an English Quaker banker, philanthropist and collector of ancient manuscripts.

Early years

Peckover was born at Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, the s ...

; his maternal grandparents were physiologist John Beresford Leathes

John Beresford Leathes DSc, MA, FRS, FRCS, FRCP (5 November 1864 – 14 September 1956) was a British physiologist and an early biochemist. He was the son of Hebrew scholar Stanley Leathes, and the brother of the poet, historian and First ...

and Russian Jewish Sonia Marie Natanson. His uncle was artist Roland Penrose

Sir Roland Algernon Penrose (14 October 1900 – 23 April 1984) was an English artist, historian and poet. He was a major promoter and collector of modern art and an associate of the surrealists in the United Kingdom. During the Second World ...

, whose son with photographer Lee Miller

Elizabeth "Lee" Miller, Lady Penrose (April 23, 1907 – July 21, 1977), was an American photographer and photojournalist. She was a fashion model in New York City in the 1920s before going to Paris, where she became a fashion and fine art ...

is Antony Penrose

Antony William Roland Penrose (born 9 September 1947) is a British photographer. The son of Sir Roland Penrose and Lee Miller, Penrose is director of the Lee Miller Archive and Penrose Collection at his parents' former home, Farley Farm House ...

. Penrose is the brother of physicist Oliver Penrose

Oliver Penrose (born 6 June 1929) is a British theoretical physicist.

He is the son of the scientist Lionel Penrose and brother of the mathematical physicist Roger Penrose, chess Grandmaster Jonathan Penrose, and geneticist Shirley Hodgson. ...

, of geneticist Shirley Hodgson

Shirley Victoria Hodgson, FRCP, FRSB (née Penrose; born 22 February 1945) is a British geneticist.

Biography

Hodgson studied at Somerville College, Oxford. She worked as a GP, then performed as locum in clinical genetics at Guy's Hospital, ...

, and of chess Grandmaster

Grandmaster (GM) is a title awarded to chess players by the world chess organization FIDE. Apart from World Champion, Grandmaster is the highest title a chess player can attain. Once achieved, the title is held for life, though exceptionally it h ...

Jonathan Penrose

Jonathan Penrose, (7 October 1933 – 30 November 2021) was an English chess player, who held the titles Grandmaster (1993) and International Correspondence Chess Grandmaster (1983). He won the British Chess Championship ten times between 1958 ...

. Their stepfather was the mathematician and computer scientist Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

.

Penrose spent World War II as a child in Canada where his father worked in London, Ontario

London (pronounced ) is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor. The city had a population of 422,324 according to the 2021 Canadian census. London is at the confluence of the Thames River, approximate ...

. Penrose studied at University College School

("Slowly but surely")

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent day school

, religion =

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Mark Beard

, r_head_label =

, r_he ...

. He attended University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

and attained a first class degree in mathematics from University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

in 1952.

In 1955, whilst a student, Penrose reintroduced the E. H. Moore

Eliakim Hastings Moore (; January 26, 1862 – December 30, 1932), usually cited as E. H. Moore or E. Hastings Moore, was an American mathematician.

Life

Moore, the son of a Methodist minister and grandson of US Congressman Eliakim H. Moore, di ...

generalised matrix inverse, also known as the Moore–Penrose inverse

In mathematics, and in particular linear algebra, the Moore–Penrose inverse of a matrix is the most widely known generalization of the inverse matrix. It was independently described by E. H. Moore in 1920, Arne Bjerhammar in 1951, and Rog ...

, after it had been reinvented by Arne Bjerhammar in 1951. Having started research under the professor of geometry and astronomy, Sir W. V. D. Hodge, Penrose finished his PhD at St John's College, Cambridge, in 1958, with a thesis on tensor methods in algebraic geometry supervised by algebraist and geometer John A. Todd. He devised and popularised the Penrose triangle

The Penrose triangle, also known as the Penrose tribar, the impossible tribar, or the impossible triangle, is a triangular impossible object, an optical illusion consisting of an object which can be depicted in a perspective drawing, but cannot e ...

in the 1950s, describing it as "impossibility in its purest form", and exchanged material with the artist M. C. Escher

Maurits Cornelis Escher (; 17 June 1898 – 27 March 1972) was a Dutch graphic artist who made mathematically inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints.

Despite wide popular interest, Escher was for most of his life neglected in t ...

, whose earlier depictions of impossible objects partly inspired it. Escher's Waterfall

A waterfall is a point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops. Waterfalls also occur where meltwater drops over the edge of a tabular iceberg or ice shelf.

Waterfalls can be formed in several wa ...

, and Ascending and Descending

''Ascending and Descending'' is a lithograph print by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher first printed in March 1960. The original print measures . The lithograph depicts a large building roofed by a never-ending staircase. Two lines of identicall ...

were in turn inspired by Penrose.

file:Penrose-dreieck.svg, The Penrose triangle

The Penrose triangle, also known as the Penrose tribar, the impossible tribar, or the impossible triangle, is a triangular impossible object, an optical illusion consisting of an object which can be depicted in a perspective drawing, but cannot e ...

As reviewer Manjit Kumar puts it:

Research and career

Penrose spent the academic year 1956–57 as an assistant lecturer at Bedford College, London and was then a research fellow at St John's College, Cambridge. During that three-year post, he married Joan Isabel Wedge, in 1959. Before the fellowship ended Penrose won aNATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

Research Fellowship for 1959–61, first at Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

and then at Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

. Returning to the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, Penrose spent two years, 1961–63, as a researcher at King's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King G ...

, before returning to the United States to spend the year 1963–64 as a visiting associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

. He later held visiting positions at Yeshiva, Princeton, and Cornell during 1966–67 and 1969.

In 1964, while a reader

A reader is a person who reads. It may also refer to:

Computing and technology

* Adobe Reader (now Adobe Acrobat), a PDF reader

* Bible Reader for Palm, a discontinued PDA application

* A card reader, for extracting data from various forms of ...

at Birkbeck College, London, (and having had his attention drawn from pure mathematics to astrophysics by the cosmologist Dennis Sciama

Dennis William Siahou Sciama, (; 18 November 1926 – 18/19 December 1999) was a British physicist who, through his own work and that of his students, played a major role in developing British physics after the Second World War. He was the PhD ...

, then at Cambridge) in the words of Kip Thorne

Kip Stephen Thorne (born June 1, 1940) is an American theoretical physicist known for his contributions in gravitational physics and astrophysics. A longtime friend and colleague of Stephen Hawking and Carl Sagan, he was the Richard P. F ...

of Caltech, "Roger Penrose revolutionised the mathematical tools that we use to analyse the properties of spacetime". Until then, work on the curved geometry of general relativity had been confined to configurations with sufficiently high symmetry for Einstein's equations to be solvable explicitly, and there was doubt about whether such cases were typical. One approach to this issue was by the use of perturbation theory

In mathematics and applied mathematics, perturbation theory comprises methods for finding an approximate solution to a problem, by starting from the exact solution of a related, simpler problem. A critical feature of the technique is a middl ...

, as developed under the leadership of John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr in ...

at Princeton. The other, and more radically innovative, approach initiated by Penrose was to overlook the detailed geometrical structure of spacetime and instead concentrate attention just on the topology of the space, or at most its conformal structure

In mathematics, conformal geometry is the study of the set of angle-preserving ( conformal) transformations on a space.

In a real two dimensional space, conformal geometry is precisely the geometry of Riemann surfaces. In space higher than two d ...

, since it is the latter – as determined by the lay of the lightcones – that determines the trajectories of lightlike geodesics, and hence their causal relationships. The importance of Penrose's epoch-making paper "Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities" was not its only result, summarised roughly as that if an object such as a dying star implodes beyond a certain point, then nothing can prevent the gravitational field getting so strong as to form some kind of singularity. It also showed a way to obtain similarly general conclusions in other contexts, notably that of the cosmological Big Bang, which he dealt with in collaboration with Dennis Sciama

Dennis William Siahou Sciama, (; 18 November 1926 – 18/19 December 1999) was a British physicist who, through his own work and that of his students, played a major role in developing British physics after the Second World War. He was the PhD ...

's most famous student, Stephen Hawking. The Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems

The Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems (after Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking) are a set of results in general relativity that attempt to answer the question of when gravitation produces singularities. The Penrose singularity theorem is ...

were inspired by Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri

Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri (14 September 1923 – 18 June 2005) was an Indian physicist, known for his research in general relativity and cosmology. His most significant contribution is the eponymous Raychaudhuri equation, which demonstrates that ...

's Raychaudhuri equation

In general relativity, the Raychaudhuri equation, or Landau–Raychaudhuri equation, is a fundamental result describing the motion of nearby bits of matter.

The equation is important as a fundamental lemma for the Penrose–Hawking singularity the ...

.

300px, Predicted view from outside the black_hole_lit_by_a_thin_accretion_disc.html" ;"title="event horizon of a black hole lit by a thin accretion disc">event horizon of a black hole lit by a thin accretion disc

It was in the local context of gravitational collapse that the contribution of Penrose was most decisive, starting with his 1969 cosmic censorship conjecture, to the effect that any ensuing singularities would be confined within a well-behaved event horizon

In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an observer. Wolfgang Rindler coined the term in the 1950s.

In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive compact ob ...

surrounding a hidden space-time region for which Wheeler coined the term black hole, leaving a visible exterior region with strong but finite curvature, from which some of the gravitational energy may be extractable by what is known as the Penrose process

The Penrose process (also called Penrose mechanism) is theorised by Sir Roger Penrose as a means whereby energy can be extracted from a rotating black hole. The process takes advantage of the ergosphere --- a region of spacetime around the black ...

, while accretion of surrounding matter may release further energy that can account for astrophysical phenomena such as quasars

A quasar is an extremely luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN). It is pronounced , and sometimes known as a quasi-stellar object, abbreviated QSO. This emission from a galaxy nucleus is powered by a supermassive black hole with a mass rangi ...

.

Following up his "weak cosmic censorship hypothesis The weak and the strong cosmic censorship hypotheses are two mathematical conjectures about the structure of gravitational singularities arising in general relativity.

Singularities that arise in the solutions of Einstein's equations are typically ...

", Penrose went on, in 1979, to formulate a stronger version called the "strong censorship hypothesis". Together with the Belinski–Khalatnikov–Lifshitz conjecture and issues of nonlinear stability, settling the censorship conjectures is one of the most important outstanding problems in general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

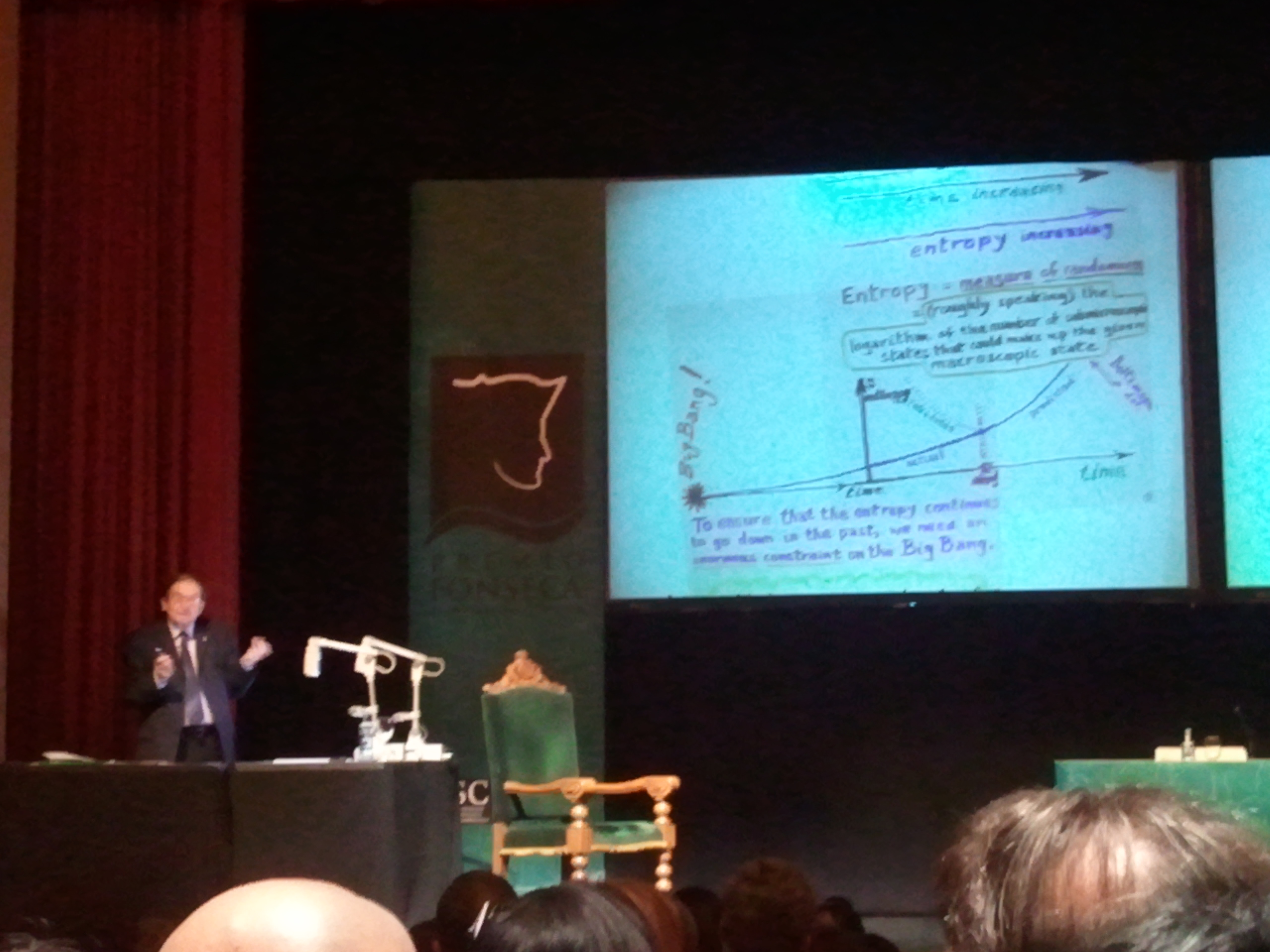

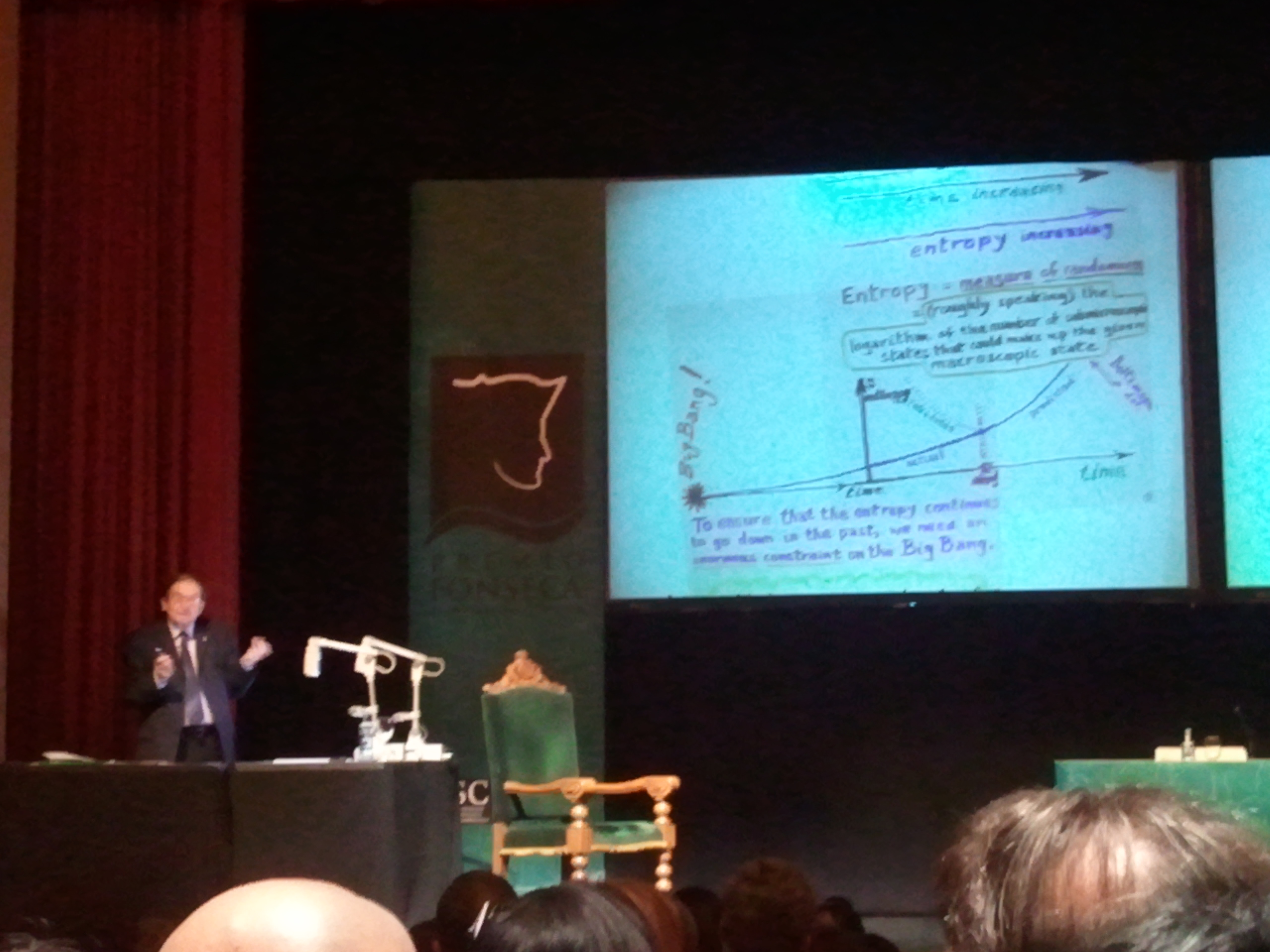

. Also from 1979, dates Penrose's influential Weyl curvature hypothesis

The Weyl curvature hypothesis, which arises in the application of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity to physical cosmology, was introduced by the British mathematician and theoretical physicist Roger Penrose in an article in 1979 in ...

on the initial conditions of the observable part of the universe and the origin of the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal experience concerning heat and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unles ...

. Penrose and James Terrell independently realised that objects travelling near the speed of light will appear to undergo a peculiar skewing or rotation. This effect has come to be called the Terrell rotation or Penrose–Terrell rotation.

twistor theory

In theoretical physics, twistor theory was proposed by Roger Penrose in 1967 as a possible path to quantum gravity and has evolved into a branch of theoretical and mathematical physics. Penrose proposed that twistor space should be the basic are ...

which maps geometric objects in Minkowski space

In mathematical physics, Minkowski space (or Minkowski spacetime) () is a combination of three-dimensional Euclidean space and time into a four-dimensional manifold where the spacetime interval between any two events is independent of the inerti ...

into the 4-dimensional complex space with the metric signature (2,2).

Penrose is well known for his 1974 discovery of Penrose tiling

A Penrose tiling is an example of an aperiodic tiling. Here, a ''tiling'' is a covering of the plane by non-overlapping polygons or other shapes, and ''aperiodic'' means that shifting any tiling with these shapes by any finite distance, without ...

s, which are formed from two tiles that can only tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

the plane nonperiodically, and are the first tilings to exhibit fivefold rotational symmetry. In 1984, such patterns were observed in the arrangement of atoms in quasicrystal

A quasiperiodic crystal, or quasicrystal, is a structure that is ordered but not periodic. A quasicrystalline pattern can continuously fill all available space, but it lacks translational symmetry. While crystals, according to the classical ...

s. Another noteworthy contribution is his 1971 invention of spin network

In physics, a spin network is a type of diagram which can be used to represent states and interactions between particles and fields in quantum mechanics. From a mathematical perspective, the diagrams are a concise way to represent multilinear f ...

s, which later came to form the geometry of spacetime

In physics, spacetime is a mathematical model that combines the three dimensions of space and one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional manifold. Spacetime diagrams can be used to visualize relativistic effects, such as why differen ...

in loop quantum gravity. He was influential in popularizing what are commonly known as Penrose diagram

In theoretical physics, a Penrose diagram (named after mathematical physicist Roger Penrose) is a two-dimensional diagram capturing the causal relations between different points in spacetime through a conformal treatment of infinity. It is an ext ...

s (causal diagrams).

In 1983, Penrose was invited to teach at Rice University

William Marsh Rice University (Rice University) is a Private university, private research university in Houston, Houston, Texas. It is on a 300-acre campus near the Houston Museum District and adjacent to the Texas Medical Center. Rice is ranke ...

in Houston, by the then provost Bill Gordon. He worked there from 1983 to 1987. His doctoral students have included Claude LeBrun

Claude R. LeBrun (born 1956) is an American mathematician who holds the position of SUNY Distinguished Professor of Mathematics at Stony Brook University. Much of his research concerns the Riemannian geometry of 4-manifolds, or related topics in ...

, Tristan Needham

Tristan Needham is a British mathematician and professor of mathematics at the University of San Francisco.

Education, career and publications

Tristan is the son of social anthropologist Rodney Needham of Oxford, England. He attended the Dragon ...

, Richard Jozsa

Richard Jozsa is an Australian mathematician who holds the Leigh Trapnell Chair in Quantum Physics at the University of Cambridge. He is a fellow of King's College, Cambridge, where his research investigates quantum information science. A p ...

, Richard S. Ward

Richard Samuel Ward FRS (born 6 September 1951) is a British mathematical physicist. He is a Professor of Mathematical & Theoretical Particle Physics at the University of Durham.

Work

Ward earned his Ph.D. from the University of Oxford in 1 ...

, Andrew Hodges

Andrew Philip Hodges (; born 1949) is a British mathematician, author and emeritus senior research fellow at Wadham College, Oxford.

Education

Hodges was born in London in 1949 and educated at Birkbeck, University of London where he was award ...

, Asghar Qadir

Asghar Qadir ( ur, اصغر قادر born 23 July 1946) ''HI'', ''SI'', ''FPAS'', is a Pakistani mathematician and a prominent cosmologist, specialised in mathematical physics and physical cosmology. He is considered one of the top mathemati ...

, John McNamara, Lane Hughston and Tim Poston

Timothy Poston (19 June 1945 – 22 August 2017) was an English mathematician and polymath best known for his work on catastrophe theory.

His early childhood was in Moscow where his father served in the British Embassy for 18 months. When his ...

.

In 2004, Penrose released '' The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe'', a 1,099-page comprehensive guide to the Laws of Physics

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow) ...

that includes an explanation of his own theory. The Penrose Interpretation predicts the relationship between quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

and general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

, and proposes that a quantum state

In quantum physics, a quantum state is a mathematical entity that provides a probability distribution for the outcomes of each possible measurement on a system. Knowledge of the quantum state together with the rules for the system's evolution i ...

remains in superposition until the difference of space-time curvature attains a significant level.

Penrose is the Francis and Helen Pentz Distinguished Visiting Professor of Physics and Mathematics at Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsylvan ...

.

An earlier universe

In 2010, Penrose reported possible evidence, based on concentric circles found in Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data of the

In 2010, Penrose reported possible evidence, based on concentric circles found in Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data of the cosmic microwave background

In Big Bang cosmology the cosmic microwave background (CMB, CMBR) is electromagnetic radiation that is a remnant from an early stage of the universe, also known as "relic radiation". The CMB is faint cosmic background radiation filling all spac ...

sky, of an earlier universe existing before the Big Bang of our own present universe. He mentions this evidence in the epilogue of his 2010 book '' Cycles of Time'', a book in which he presents his reasons, to do with Einstein's field equations

In the general theory of relativity, the Einstein field equations (EFE; also known as Einstein's equations) relate the geometry of spacetime to the distribution of matter within it.

The equations were published by Einstein in 1915 in the form ...

, the Weyl curvature C, and the Weyl curvature hypothesis

The Weyl curvature hypothesis, which arises in the application of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity to physical cosmology, was introduced by the British mathematician and theoretical physicist Roger Penrose in an article in 1979 in ...

(WCH), that the transition at the Big Bang could have been smooth enough for a previous universe to survive it. He made several conjectures about C and the WCH, some of which were subsequently proved by others, and he also popularized his conformal cyclic cosmology

Conformal cyclic cosmology (CCC) is a cosmological model in the framework of general relativity and proposed by theoretical physicist Roger Penrose. In CCC, the universe iterates through infinite cycles, with the future timelike infinity (i.e. the ...

(CCC) theory. In this theory, Penrose postulates that at the end of the universe all matter is eventually contained within black holes which subsequently evaporate via Hawking radiation

Hawking radiation is theoretical black body radiation that is theorized to be released outside a black hole's event horizon because of relativistic quantum effects. It is named after the physicist Stephen Hawking, who developed a theoretical a ...

. At this point, everything contained within the universe consists of photons

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they alway ...

which "experience" neither time nor space. There is essentially no difference between an infinitely large universe consisting only of photons and an infinitely small universe consisting only of photons. Therefore, a singularity for a Big Bang and an infinitely expanded universe are equivalent.

In simple terms, Penrose believes that the singularity in Einstein's field equation

In the general theory of relativity, the Einstein field equations (EFE; also known as Einstein's equations) relate the geometry of spacetime to the distribution of matter within it.

The equations were published by Einstein in 1915 in the form ...

at the Big Bang is only an apparent singularity, similar to the well-known apparent singularity at the event horizon

In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an observer. Wolfgang Rindler coined the term in the 1950s.

In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive compact ob ...

of a black hole. The latter singularity can be removed by a change of coordinate system

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine the position of the points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as Euclidean space. The order of the coordinates is sig ...

, and Penrose proposes a different change of coordinate system that will remove the singularity at the big bang. One implication of this is that the major events at the Big Bang can be understood without unifying general relativity and quantum mechanics, and therefore we are not necessarily constrained by the Wheeler–DeWitt equation

The Wheeler–DeWitt equation for theoretical physics and applied mathematics, is a field equation attributed to John Archibald Wheeler and Bryce DeWitt. The equation attempts to mathematically combine the ideas of quantum mechanics and general ...

, which disrupts time. Alternatively, one can use the Einstein–Maxwell–Dirac equations.

Consciousness

The Emperor's New Mind

''The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and The Laws of Physics'' is a 1989 book by the mathematical physicist Sir Roger Penrose.

Penrose argues that human consciousness is non-algorithmic, and thus is not capable of being modeled ...

'' (1989), he argues that known laws of physics are inadequate to explain the phenomenon of consciousness. Penrose proposes the characteristics this new physics may have and specifies the requirements for a bridge between classical and quantum mechanics (what he calls ''correct quantum gravity''). Penrose uses a variant of Turing's halting theorem to demonstrate that a system can be deterministic without being algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algorithms are used as specificat ...

ic. (For example, imagine a system with only two states, ON and OFF. If the system's state is ON when a given Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algori ...

halts and OFF when the Turing machine does not halt, then the system's state is completely determined by the machine; nevertheless, there is no algorithmic way to determine whether the Turing machine stops.)

Penrose believes that such deterministic yet non-algorithmic processes may come into play in the quantum mechanical wave function reduction, and may be harnessed by the brain. He argues that computers today are unable to have intelligence because they are algorithmically deterministic systems. He argues against the viewpoint that the rational processes of the mind are completely algorithmic and can thus be duplicated by a sufficiently complex computer. This contrasts with supporters of strong artificial intelligence, who contend that thought can be simulated algorithmically. He bases this on claims that consciousness transcends formal logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

because factors such as the insolubility of the halting problem and Gödel's incompleteness theorem prevent an algorithmically based system of logic from reproducing such traits of human intelligence as mathematical insight. These claims were originally espoused by the philosopher John Lucas (philosopher), John Lucas of Merton College, Oxford, Merton College, University of Oxford, Oxford. G. Hirase has paraphrased Penrose' argument and reinforced it.

The Penrose–Lucas argument about the implications of Gödel's incompleteness theorem for computational theories of human intelligence has been criticised by mathematicians, computer scientists and philosophers. Many experts in these fields assert that Penrose's argument fails, though different authors may choose different aspects of the argument to attack. Marvin Minsky, a leading proponent of artificial intelligence, was particularly critical, stating that Penrose "tries to show, in chapter after chapter, that human thought cannot be based on any known scientific principle." Minsky's position is exactly the opposite – he believed that humans are, in fact, machines, whose functioning, although complex, is fully explainable by current physics. Minsky maintained that "one can carry that quest [for scientific explanation] too far by only seeking new basic principles instead of attacking the real detail. This is what I see in Penrose's quest for a new basic principle of physics that will account for consciousness."

Penrose responded to criticism of ''The Emperor's New Mind'' with his follow-up 1994 book ''Shadows of the Mind'', and in 1997 with ''The Large, the Small and the Human Mind''. In those works, he also combined his observations with those of anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff.

Penrose and Hameroff have argued that consciousness is the result of quantum gravity effects in microtubules, which they dubbed Orch-OR (orchestrated objective reduction). Max Tegmark, in a paper in ''Physical Review E'', calculated that the time scale of neuron firing and excitations in microtubules is slower than the quantum decoherence, decoherence time by a factor of at least 10,000,000,000. The reception of the paper is summed up by this statement in Tegmark's support: "Physicists outside the fray, such as IBM's John A. Smolin, say the calculations confirm what they had suspected all along. 'We're not working with a brain that's near absolute zero. It's reasonably unlikely that the brain evolved quantum behavior'". Tegmark's paper has been widely cited by critics of the Penrose–Hameroff position.

In their reply to Tegmark's paper, also published in ''Physical Review E'', the physicists Scott Hagan, Jack Tuszyński and Hameroff claimed that Tegmark did not address the Orch-OR model, but instead a model of his own construction. This involved superpositions of quanta separated by 24 nm rather than the much smaller separations stipulated for Orch-OR. As a result, Hameroff's group claimed a decoherence time seven orders of magnitude greater than Tegmark's, but still well short of the 25 ms required if the quantum processing in the theory was to be linked to the 40 Hz gamma synchrony, as Orch-OR suggested. To bridge this gap, the group made a series of proposals. They supposed that the interiors of neurons could alternate between liquid and gel states. In the gel state, it was further hypothesized that the water electrical dipoles are oriented in the same direction, along the outer edge of the microtubule tubulin subunits. Hameroff et al. proposed that this ordered water could screen any quantum coherence within the tubulin of the microtubules from the environment of the rest of the brain. Each tubulin also has a tail extending out from the microtubules, which is negatively charged, and therefore attracts positively charged ions. It is suggested that this could provide further screening. Further to this, there was a suggestion that the microtubules could be pumped into a coherent state by biochemical energy. Finally, he suggested that the configuration of the microtubule lattice might be suitable for quantum error correction, a means of holding together quantum coherence in the face of environmental interaction.

Hameroff, in a lecture in part of a Google Tech talks series exploring quantum biology, gave an overview of current research in the area, and responded to subsequent criticisms of the Orch-OR model. In addition to this, a 2011 paper by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff published in the ''Journal of Cosmology'' gives an updated model of their Orch-OR theory, in light of criticisms, and discusses the place of consciousness within the universe.

Phillip Tetlow, although himself supportive of Penrose's views, acknowledges that Penrose's ideas about the human thought process are at present a minority view in scientific circles, citing Minsky's criticisms and quoting science journalist Charles Seife's description of Penrose as "one of a handful of scientists" who believe that the nature of consciousness suggests a quantum process.

In January 2014, Hameroff and Penrose ventured that a discovery of quantum vibrations in microtubules by Anirban Bandyopadhyay of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan supports the hypothesis of Orchestrated objective reduction, Orch-OR theory. A reviewed and updated version of the theory was published along with critical commentary and debate in the March 2014 issue of ''Physics of Life Reviews''.

Finally, he suggested that the configuration of the microtubule lattice might be suitable for quantum error correction, a means of holding together quantum coherence in the face of environmental interaction.

Hameroff, in a lecture in part of a Google Tech talks series exploring quantum biology, gave an overview of current research in the area, and responded to subsequent criticisms of the Orch-OR model. In addition to this, a 2011 paper by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff published in the ''Journal of Cosmology'' gives an updated model of their Orch-OR theory, in light of criticisms, and discusses the place of consciousness within the universe.

Phillip Tetlow, although himself supportive of Penrose's views, acknowledges that Penrose's ideas about the human thought process are at present a minority view in scientific circles, citing Minsky's criticisms and quoting science journalist Charles Seife's description of Penrose as "one of a handful of scientists" who believe that the nature of consciousness suggests a quantum process.

In January 2014, Hameroff and Penrose ventured that a discovery of quantum vibrations in microtubules by Anirban Bandyopadhyay of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan supports the hypothesis of Orchestrated objective reduction, Orch-OR theory. A reviewed and updated version of the theory was published along with critical commentary and debate in the March 2014 issue of ''Physics of Life Reviews''.

Publications

His popular publications include: * ''The Emperor's New Mind, The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and The Laws of Physics'' (1989) * ''Shadows of the Mind, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness'' (1994) * '' The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe'' (2004) * ''Cycles of Time, Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe'' (2010) * ''Fashion, Faith, and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe'' (2016) His co-authored publications include: * ''The Nature of Space and Time'' (with Stephen Hawking) (1996) * ''The Large, the Small and the Human Mind'' (with Abner Shimony, Nancy Cartwright (philosopher), Nancy Cartwright, and Stephen Hawking) (1997) * ''White Mars: The Mind Set Free'' (with Brian Aldiss) (1999) His academic books include: * ''Techniques of Differential Topology in Relativity'' (1972, ) * ''Spinors and Space-Time: Volume 1, Two-Spinor Calculus and Relativistic Fields'' (with Wolfgang Rindler, 1987) (paperback) * ''Spinors and Space-Time: Volume 2, Spinor and Twistor Methods in Space-Time Geometry'' (with Wolfgang Rindler, 1988) (reprint), (paperback) His forewords to other books include: * Foreword t“The Map and the Territory: Exploring the foundations of science, thought and reality”

by Shyam Wuppuluri and Francisco Antonio Doria. Published by Springer in "The Frontiers Collection", 2018. * Foreword t

''Beating the Odds: The Life and Times of E. A. Milne''

written by Meg Weston Smith. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co in June 2013. * Foreword t

"A Computable Universe"

by Hector Zenil. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co in December 2012. * Foreword to ''Quantum Aspects of Life'' by Derek Abbott, Paul C. W. Davies, and Arun K. Pati. Published by Imperial College Press in 2008. * Foreword t

''Fearful Symmetry''

by Anthony Zee's. Published by Princeton University Press in 2007.

Awards and honours

Penrose has been awarded many prizes for his contributions to science.

In 1971, he was awarded the Dannie Heineman Prize for Astrophysics. He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1972, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1972. In 1975, Stephen Hawking and Penrose were jointly awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1985, he was awarded the Royal Society Royal Medal. Along with Stephen Hawking, he was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics, Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics in 1988.

In 1989, Penrose was awarded the Dirac Prize, Dirac Medal and Prize of the British Institute of Physics. He is also made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics (HonFInstP).

In 1990, Penrose was awarded the Albert Einstein Medal for outstanding work related to the work of Albert Einstein by the Albert Einstein Society. In 1991, he was awarded the Naylor Prize of the London Mathematical Society. From 1992 to 1995, he served as President of th

Penrose has been awarded many prizes for his contributions to science.

In 1971, he was awarded the Dannie Heineman Prize for Astrophysics. He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1972, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1972. In 1975, Stephen Hawking and Penrose were jointly awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1985, he was awarded the Royal Society Royal Medal. Along with Stephen Hawking, he was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics, Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics in 1988.

In 1989, Penrose was awarded the Dirac Prize, Dirac Medal and Prize of the British Institute of Physics. He is also made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics (HonFInstP).

In 1990, Penrose was awarded the Albert Einstein Medal for outstanding work related to the work of Albert Einstein by the Albert Einstein Society. In 1991, he was awarded the Naylor Prize of the London Mathematical Society. From 1992 to 1995, he served as President of thInternational Society on General Relativity and Gravitation

In 1994, Penrose was Knight Bachelor, knighted for services to science. In the same year, he was also awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) by the University of Bath, and became a member of Polish Academy of Sciences. In 1998, he was elected Foreign Associate of the United States National Academy of Sciences. In 2000, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Merit (OM). In 2004, he was awarded the De Morgan Medal for his wide and original contributions to mathematical physics. To quote the citation from the London Mathematical Society: In 2005, Penrose was awarded an Honorary degree, honorary doctorate by Warsaw University and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium), and in 2006 by the University of York. In 2006, he also won the Dirac Medal given by the University of New South Wales. In 2008, Penrose was awarded the Copley Medal. He is also a Distinguished Supporter of Humanists UK and one of the patrons of the Oxford University Scientific Society. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2011. The same year, he was also awarded the Fonseca Prize by the University of Santiago de Compostela. In 2012, Penrose was awarded the Richard R. Ernst Medal by ETH Zürich for his contributions to science and strengthening the connection between science and society. In 2015 Penrose was awarded an honorary doctorate by CINVESTAV, CINVESTAV-IPN (Mexico). In 2017, he was awarded the Commandino Medal at the Urbino University for his contributions to the history of science. In 2020, Penrose was awarded one half of the

Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity, a half-share also going to Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for the discovery of a Galactic Center#Supermassive black hole, supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy.

Personal life

Penrose married Vanessa Thomas, director of Academic Development at Cokethorpe School and former head of mathematics at Abingdon School, with whom he has one son. He has three sons from a previous marriage to American Joan Isabel Penrose (née Wedge), whom he married in 1959.Religious views

During an interview with BBC Radio 4 on 25 September 2010, Penrose stated, "I'm not a believer myself. I don't believe in established religions of any kind." He regards himself as an agnostic. In the 1991 film ''A Brief History of Time (film), A Brief History of Time'', he also said, "I think I would say that the universe has a purpose, it's not somehow just there by chance … some people, I think, take the view that the universe is just there and it runs along—it's a bit like it just sort of computes, and we happen somehow by accident to find ourselves in this thing. But I don't think that's a very fruitful or helpful way of looking at the universe, I think that there is something much deeper about it." Penrose is a patron of Humanists UK.References

Notes

External links

Awake in the Universe

– Penrose debates how creativity, the most elusive of faculties, has helped us unlock the country of the mind and the mysteries of the cosmos with Bonnie Greer. * * – Penrose was one of the principal interviewees in a BBC documentary about the mathematics of infinity directed by David Malone (independent filmmaker), David Malone * Penrose's new theory "Aeons Before the Big Bang?": ** Original 2005 lecture

"Before the Big Bang? A new perspective on the Weyl curvature hypothesis"

(Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge, 11 November 2005). ** Original publication

"Before the Big Bang: an outrageous new perspective and its implications for particle physics".

''Proceedings of EPAC 2006''. Edinburgh. 2759–2762 (cf. also Hill, C.D. & Nurowski, P. (2007

"On Penrose's 'Before the Big Bang' ideas"

Ithaca) ** Revised 2009 lecture

"Aeons Before the Big Bang?"

(Georgia Institute of Technology, Center for Relativistic Astrophysics) **

Roger Penrose

on ''The Forum (BBC World Service), The Forum'' *

Hilary Putnam's review of Penrose's 'Shadows of the Mind' claiming that Penrose's use of Godel's Incompleteness Theorem is fallacious

**

Penrose Tiling found in Islamic Architecture

* ** "[https://web.archive.org/web/20051024022835/http://www.quantumconsciousness.org/pdfs/decoherence.pdf Biological feasibility of quantum states in the brain]" – (a disputation of Tegmark's result by Hagan, Hameroff, and Tuszyński) **

Tegmarks's rejoinder to Hagan ''et al.''

* – D. Trull about Penrose's lawsuit concerning the use of his Penrose tilings on toilet paper

(''Plus Magazine'')

Penrose's Gifford Lecture biography

Quantum-Mind

Audio: Roger Penrose in conversation on the BBC World Service discussion show

Roger Penrose speaking about Hawking's new book on Premier Christian Radio

"The Cyclic Universe – A conversation with Roger Penrose"

''Ideas Roadshow'', 2013

Forbidden crystal symmetry in mathematics and architecture

filmed event at the Royal Institution, October 2013

''Oxford Mathematics Interviews'': "Extra Time: Professor Sir Roger Penrose in conversation

with

Andrew Hodges

Andrew Philip Hodges (; born 1949) is a British mathematician, author and emeritus senior research fellow at Wadham College, Oxford.

Education

Hodges was born in London in 1949 and educated at Birkbeck, University of London where he was award ...

." These two films explore the development of Sir Roger Penrose's thought over more than 60 years, ending with his most recent theories and predictions. 51 min and 42 min. (Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford, Mathematical Institute)

BBC Radio 4 – The Life Scientific – Roger Penrose on Black Holes – 22 November 2016

Sir Roger Penrose talks to Jim Al-Khalili about his trailblazing work on how black holes form, the problems with quantum physics and his portrayal in films about Stephen Hawking.

The Penrose Institute

Website

A chess problem holds the key to human consciousness?

Chessbase * {{DEFAULTSORT:Penrose, Roger 1931 births Living people People from Colchester 20th-century British mathematicians Mathematics popularizers 20th-century British philosophers 20th-century British physicists 21st-century British mathematicians 21st-century British philosophers 21st-century British physicists Academics of Birkbeck, University of London Academics of King's College London Albert Einstein Medal recipients Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of London Alumni of University College London British expatriate academics in the United States British Nobel laureates British consciousness researchers and theorists English agnostics English humanists English expatriates in the United States British geometers English people of Russian-Jewish descent English science writers Recreational mathematicians Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford Knights Bachelor Mathematical physicists Members of the Order of Merit Nobel laureates in Physics Pennsylvania State University faculty People educated at University College School Philosophers of science Professors of Gresham College Quantum mind Quantum physicists Recipients of the Copley Medal British relativity theorists Rice University faculty Rouse Ball Professors of Mathematics (University of Oxford) Royal Medal winners Wolf Prize in Physics laureates English people of Irish descent Recipients of the Dalton Medal