Sir Robert Boyle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an

Having made several visits to his Irish estates beginning in 1647, Robert moved to Ireland in 1652 but became frustrated at his inability to make progress in his chemical work. In one letter, he described Ireland as "a barbarous country where chemical spirits were so misunderstood and chemical instruments so unprocurable that it was hard to have any Hermetic thoughts in it."

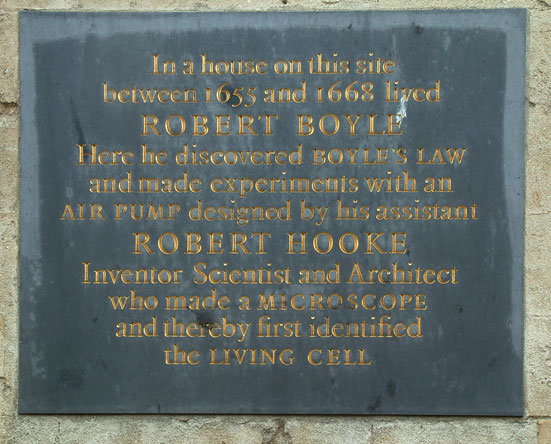

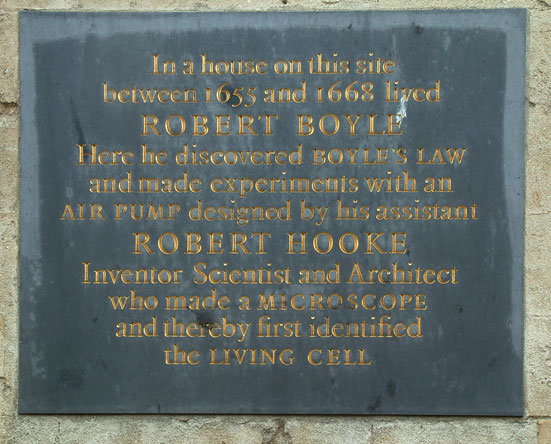

In 1654, Boyle left Ireland for Oxford to pursue his work more successfully. An inscription can be found on the wall of

Having made several visits to his Irish estates beginning in 1647, Robert moved to Ireland in 1652 but became frustrated at his inability to make progress in his chemical work. In one letter, he described Ireland as "a barbarous country where chemical spirits were so misunderstood and chemical instruments so unprocurable that it was hard to have any Hermetic thoughts in it."

In 1654, Boyle left Ireland for Oxford to pursue his work more successfully. An inscription can be found on the wall of  In 1663 the Invisible College became The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, and the charter of incorporation granted by

In 1663 the Invisible College became The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, and the charter of incorporation granted by

In 1669 his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very extraordinary", on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his spirits, range his papers", and prepare some important chemical investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy to the studious disciples of that art", but of which he did not make known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and he died on 31 December that year, just a week after the death of his sister, Katherine, in whose home he had lived and with whom he had shared scientific pursuits for more than twenty years. Boyle died from paralysis. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend, Bishop

In 1669 his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very extraordinary", on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his spirits, range his papers", and prepare some important chemical investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy to the studious disciples of that art", but of which he did not make known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and he died on 31 December that year, just a week after the death of his sister, Katherine, in whose home he had lived and with whom he had shared scientific pursuits for more than twenty years. Boyle died from paralysis. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend, Bishop

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which  Robert Boyle was an

Robert Boyle was an

As a founder of the Royal Society, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1663. Boyle's law is named in his honour. The

As a founder of the Royal Society, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1663. Boyle's law is named in his honour. The

The following are some of the more important of his works:

* 1660 – ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects''

* 1661 – ''

The following are some of the more important of his works:

* 1660 – ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects''

* 1661 – ''

File:Boyle-2.jpg, alt=, 1665 copy of "New Experiments and Observations upon Cold"

File:Boyle-1.jpg, alt=, 1661 copy of Boyle "Certain Physiological Essays, Written at Distant Times, and on Several Occasions"

File:Boyle-1-2.jpg, alt=, First page of "Certain Physiological Essays, Written at Distant Times, and on Several Occasions" (1661)

File:Boyle-3-1.jpg, alt=, 1725 edition "The Philosophical Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle," volumes 1-3

File:Boyle-3-2.jpg, alt=, First page of a 1725 edition "The Philosophical Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle," volumes 1-3

''Robert Boyle, 1627–91: Scrupulosity and Science''

The Boydell Press, 2000 * Principe, Lawrence

''The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest''

Princeton University Press, 1998 * Shapin, Stephen; Schaffer, Simon, '' Leviathan and the Air-Pump.'' * Ben-Zaken, Avner, "Exploring the Self, Experimenting Nature", i

''Reading Hayy Ibn-Yaqzan: A Cross-Cultural History of Autodidacticism''

(Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), pp. 101–126. ;Boyle's published works online

''The Sceptical Chymist''

– Project Gutenberg

''Essay on the Virtue of Gems''

– Gem and Diamond Foundation

''Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours''

– Gem and Diamond Foundation

''Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours''

– Project Gutenberg

University of London

''Hydrostatical Paradoxes''

– Google Books

Robert Boyle

''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' *

Readable versions of Excellence of the mechanical hypothesis, Excellence of theology, and Origin of forms and qualities

Robert Boyle Project, Birkbeck, University of London

* ttp://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1997/PSCF3-97Woodall.html The Relationship between Science and Scripture in the Thought of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest : Including Boyle's "Lost" Dialogue on the Transmutation of Metals

''Experimenta et considerationes de coloribus''

– digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Boyle, Robert 1627 births Irish Anglicans 1691 deaths 17th-century Anglo-Irish people Discoverers of chemical elements English alchemists 17th-century English chemists English physicists Founder Fellows of the Royal Society Independent scientists Irish alchemists Irish chemists Irish physicists People educated at Eton College People from Lismore, County Waterford Philosophers of science

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

natural philosopher, chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

, alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscience, protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in Chinese alchemy, C ...

and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of modern chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

, and one of the pioneers of modern experimental scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific m ...

. He is best known for Boyle's law, which describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and e ...

and volume

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). The de ...

of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system. Among his works, ''The Sceptical Chymist

''The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes'' is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the ''Sceptical Chymist'' presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of corp ...

'' is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry. He was a devout and pious Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

and is noted for his writings in theology.

Biography

Early years

Boyle was born at Lismore Castle, inCounty Waterford

County Waterford ( ga, Contae Phort Láirge) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is part of the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region. It is named ...

, Ireland, the seventh son and fourteenth child of The 1st Earl of Cork ('the Great Earl of Cork') and Catherine Fenton. Lord Cork, then known simply as Richard Boyle, had arrived in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1588 during the Tudor plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, angl ...

and obtained an appointment as a deputy escheator. He had amassed enormous wealth and landholdings by the time Robert was born, and had been created Earl of Cork in October 1620. Catherine Fenton, Countess

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility.L. G. Pine, Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty'' ...

of Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, was the daughter of Sir Geoffrey Fenton, the former Secretary of State for Ireland

The Principal Secretary of State, or Principal Secretary of the Council, was a government office in the Kingdom of Ireland. It was abolished in 1801 when Ireland became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland under the Acts of Uni ...

, who was born in Dublin in 1539, and Alice Weston, the daughter of Robert Weston

Robert Weston (c.1515 – 20 May 1573) was an English civil lawyer, who was Dean of the Arches and Lord Chancellor of Ireland in the time of Queen Elizabeth.

Life

Robert Weston was the seventh son of John Weston (c. 1470 - c. 1550), a trades ...

, who was born in Lismore in 1541.

As a child, Boyle was raised by a wet nurse, as were his elder brothers. Boyle received private tutoring in Latin, Greek, and French and when he was eight years old, following the death of his mother, he, and his brother Francis, were sent to Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

in England. His father's friend, Sir Henry Wotton

Sir Henry Wotton (; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg, in 1604, he famously said, "An ambassador is an honest gentlema ...

, was then the provost of the college.

During this time, his father hired a private tutor, Robert Carew, who had knowledge of Irish, to act as private tutor to his sons in Eton. However, "only Mr. Robert sometimes desires it rish

Rish ( bg, Риш Riš) is a village in Smyadovo Municipality, Shumen Province, Bulgaria, with a population of 604 as of 2019.

Population

According to the 2011 Census, the population of Rish consists mainly of Bulgarian Turks (72.6%), followe ...

and is a little entered in it", but despite the "many reasons" given by Carew to turn their attentions to it, "they practice the French and Latin but they affect not the Irish". After spending over three years at Eton, Robert travelled abroad with a French tutor. They visited Italy in 1641 and remained in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

during the winter of that year studying the "paradoxes of the great star-gazer" Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

, who was elderly but still living in 1641.

Middle years

Robert returned to England fromcontinental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

in mid-1644 with a keen interest in scientific research. His father, Lord Cork, had died the previous year and had left him the manor of Stalbridge in Dorset as well as substantial estates in County Limerick in Ireland that he had acquired. Robert then made his residence at Stalbridge House, between 1644 and 1652, and settled a laboratory where he conducted many experiments. From that time, Robert devoted his life to scientific research and soon took a prominent place in the band of enquirers, known as the " Invisible College", who devoted themselves to the cultivation of the "new philosophy". They met frequently in London, often at Gresham College, and some of the members also had meetings at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

.

Having made several visits to his Irish estates beginning in 1647, Robert moved to Ireland in 1652 but became frustrated at his inability to make progress in his chemical work. In one letter, he described Ireland as "a barbarous country where chemical spirits were so misunderstood and chemical instruments so unprocurable that it was hard to have any Hermetic thoughts in it."

In 1654, Boyle left Ireland for Oxford to pursue his work more successfully. An inscription can be found on the wall of

Having made several visits to his Irish estates beginning in 1647, Robert moved to Ireland in 1652 but became frustrated at his inability to make progress in his chemical work. In one letter, he described Ireland as "a barbarous country where chemical spirits were so misunderstood and chemical instruments so unprocurable that it was hard to have any Hermetic thoughts in it."

In 1654, Boyle left Ireland for Oxford to pursue his work more successfully. An inscription can be found on the wall of University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the univer ...

, the High Street at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

(now the location of the Shelley Memorial

The Shelley Memorial is a memorial to the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) at University College, Oxford, University College, Oxford, England, the college that he briefly attended and from which he was expelled for writing the 181 ...

), marking the spot where Cross Hall stood until the early 19th century. It was here that Boyle rented rooms from the wealthy apothecary who owned the Hall.

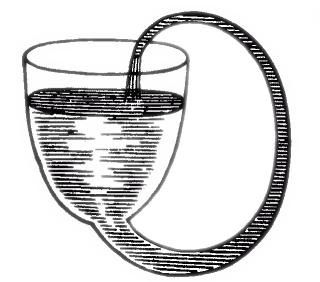

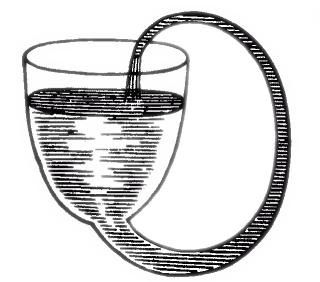

Reading in 1657 of Otto von Guericke

Otto von Guericke ( , , ; spelled Gericke until 1666; November 20, 1602 – May 11, 1686 ; November 30, 1602 – May 21, 1686 ) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. His pioneering scientific work, the development of experimental me ...

's air pump, he set himself, with the assistance of Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, to devise improvements in its construction, and with the result, the "machina Boyleana" or "Pneumatical Engine", finished in 1659, he began a series of experiments on the properties of air and coined the term factitious airs. An account of Boyle's work with the air pump was published in 1660 under the title ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects''.

Among the critics of the views put forward in this book was a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, Francis Line

Francis Line, SJ (1595 – 15 November 1675), also known as Linus of Liège, was a Jesuit priest and scientist. He is known for inventing a magnetic clock. He is noted as a contemporary critic of the theories and work of Isaac Newton. He also ch ...

(1595–1675), and it was while answering his objections that Boyle made his first mention of the law that the volume of a gas varies inversely to the pressure of the gas, which among English-speaking people is usually called Boyle's Law after his name. The person who originally formulated the hypothesis was Henry Power

Henry Power (1623–1668) was an English physician and experimenter, one of the first elected fellows of the Royal Society.

Life

Power matriculated as a pensioner of Christ's College, Cambridge, in 1641 and graduated a Bachelor of Arts in 1644. ...

in 1661. Boyle in 1662 included a reference to a paper written by Power, but mistakenly attributed it to Richard Towneley

Richard Towneley (10 October 1629 – 22 January 1707) was an English mathematician, natural philosopher and astronomer, resident at Towneley Hall, near Burnley in Lancashire. His uncle was the antiquarian and mathematician Christopher Townele ...

. In continental Europe the hypothesis is sometimes attributed to Edme Mariotte

Edme Mariotte (; ; c. 162012 May 1684) was a French physicist and priest ( abbé). He is particularly well known for formulating Boyle's law independently of Robert Boyle. Mariotte is also credited with designing the first Newton's cradle.

Biogr ...

, although he did not publish it until 1676 and was likely aware of Boyle's work at the time.

In 1663 the Invisible College became The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, and the charter of incorporation granted by

In 1663 the Invisible College became The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, and the charter of incorporation granted by Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child of ...

named Boyle a member of the council. In 1680 he was elected president of the society, but declined the honour from a scruple about oaths.

He made a "wish list" of 24 possible inventions which included "the prolongation of life", the "art of flying", "perpetual light", "making armour light and extremely hard", "a ship to sail with all winds, and a ship not to be sunk", "practicable and certain way of finding longitudes", "potent drugs to alter or exalt imagination, waking, memory and other functions and appease pain, procure innocent sleep, harmless dreams, etc.". All but a few of the 24 have come true.

In 1668 he left Oxford for London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

where he resided at the house of his elder sister Katherine Jones, Lady Ranelagh, in Pall Mall. He experimented in the laboratory she had in her home and attended her salon of intellectuals interested in the sciences. The siblings maintained "a lifelong intellectual partnership, where brother and sister shared medical remedies, promoted each other's scientific ideas, and edited each other's manuscripts." His contemporaries widely acknowledged Katherine's influence on his work, but later historiographers dropped discussion of her accomplishments and relationship to her brother from their histories.

Later years

In 1669 his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very extraordinary", on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his spirits, range his papers", and prepare some important chemical investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy to the studious disciples of that art", but of which he did not make known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and he died on 31 December that year, just a week after the death of his sister, Katherine, in whose home he had lived and with whom he had shared scientific pursuits for more than twenty years. Boyle died from paralysis. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend, Bishop

In 1669 his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very extraordinary", on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his spirits, range his papers", and prepare some important chemical investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy to the studious disciples of that art", but of which he did not make known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and he died on 31 December that year, just a week after the death of his sister, Katherine, in whose home he had lived and with whom he had shared scientific pursuits for more than twenty years. Boyle died from paralysis. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend, Bishop Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet (18 September 1643 – 17 March 1715) was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was highly respected as a cleric, a preacher, an academic, ...

. In his will, Boyle endowed a series of lectures that came to be known as the Boyle Lectures

The Boyle Lectures are named after Robert Boyle, a prominent natural philosopher of the 17th century and son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Under the terms of his Will, Robert Boyle endowed a series of lectures or sermons (originally eight e ...

.

Scientific investigator

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

espoused in the '' Novum Organum''. Yet he would not avow himself a follower of Bacon, or indeed of any other teacher.

On several occasions he mentions that to keep his judgment as unprepossessed as might be with any of the modern theories of philosophy, until he was "provided of experiments" to help him judge of them. He refrained from any study of the atomical and the Cartesian Cartesian means of or relating to the French philosopher René Descartes—from his Latinized name ''Cartesius''. It may refer to:

Mathematics

*Cartesian closed category, a closed category in category theory

*Cartesian coordinate system, modern ...

systems, and even of the Novum Organum itself, though he admits to "transiently consulting" them about a few particulars. Nothing was more alien to his mental temperament than the spinning of hypotheses. He regarded the acquisition of knowledge as an end in itself, and in consequence he gained a wider outlook on the aims of scientific inquiry than had been enjoyed by his predecessors for many centuries. This, however, did not mean that he paid no attention to the practical application of science nor that he despised knowledge which tended to use.

Robert Boyle was an

Robert Boyle was an alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscience, protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in Chinese alchemy, C ...

; and believing the transmutation of metals to be a possibility, he carried out experiments in the hope of achieving it; and he was instrumental in obtaining the repeal, in 1689, of the statute of Henry IV against multiplying

Multiplication (often denoted by the cross symbol , by the mid-line dot operator , by juxtaposition, or, on computers, by an asterisk ) is one of the four elementary mathematical operations of arithmetic, with the other ones being addition ...

gold and silver. With all the important work he accomplished in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

– the enunciation of Boyle's law, the discovery of the part taken by air in the propagation of sound, and investigations on the expansive force of freezing water, on specific gravities and refractive

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomeno ...

powers, on crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

s, on electricity, on colour, on hydrostatics, etc. – chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

was his peculiar and favourite study. His first book on the subject was ''The Sceptical Chymist'', published in 1661, in which he criticised the "experiments whereby vulgar Spagyrists are wont to endeavour to evince their Salt, Sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

and Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

to be the true Principles of Things." For him chemistry was the science of the composition of substances, not merely an adjunct to the arts of the alchemist or the physician.

He endorsed the view of elements as the undecomposable constituents of material bodies; and made the distinction between mixture

In chemistry, a mixture is a material made up of two or more different chemical substances which are not chemically bonded. A mixture is the physical combination of two or more substances in which the identities are retained and are mixed in the ...

s and compounds. He made considerable progress in the technique of detecting their ingredients, a process which he designated by the term "analysis". He further supposed that the elements were ultimately composed of particle

In the Outline of physical science, physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscule in older texts) is a small wikt:local, localized physical body, object which can be described by several physical property, physical or chemical property, chemical ...

s of various sorts and sizes, into which, however, they were not to be resolved in any known way. He studied the chemistry of combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

and of respiration, and conducted experiments in physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, where, however, he was hampered by the "tenderness of his nature" which kept him from anatomical dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

s, especially vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

s, though he knew them to be "most instructing".

Theological interests

In addition to philosophy, Boyle devoted much time to theology, showing a very decided leaning to the practical side and an indifference to controversialpolemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

s. At the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of the king in 1660, he was favourably received at court and in 1665 would have received the provostship of Eton College had he agreed to take holy orders, but this he refused to do on the ground that his writings on religious subjects would have greater weight coming from a layman than a paid minister of the Church.

Moreover, Boyle incorporated his scientific interests into his theology, believing that natural philosophy could provide powerful evidence for the existence of God. In works such as ''Disquisition about the Final Causes of Natural Things'' (1688), for instance, he criticised contemporary philosophers – such as René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

– who denied that the study of nature could reveal much about God. Instead, Boyle argued that natural philosophers could use the design apparently on display in some parts of nature to demonstrate God's involvement with the world. He also attempted to tackle complex theological questions using methods derived from his scientific practices. In ''Some Physico-Theological Considerations about the Possibility of the Resurrection'' (1675), he used a chemical experiment known as the reduction to the pristine state as part of an attempt to demonstrate the physical possibility of the resurrection of the body. Throughout his career, Boyle tried to show that science could lend support to Christianity.

As a director of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

he spent large sums in promoting the spread of Christianity in the East, contributing liberally to missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

societies and to the expenses of translating the Bible or portions of it into various languages. Boyle supported the policy that the Bible should be available in the vernacular language of the people. An Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

version of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

was published in 1602 but was rare in Boyle's adult life. In 1680–85 Boyle personally financed the printing of the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, in Irish. In this respect, Boyle's attitude to the Irish language differed from the Protestant Ascendancy class in Ireland at the time, which was generally hostile to the language and largely opposed the use of Irish (not only as a language of religious worship).

Boyle also had a monogenist

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all human races. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the ...

perspective about race origin. He was a pioneer studying races, and he believed that all human beings, no matter how diverse their physical differences, came from the same source: Adam and Eve. He studied reported stories of parents' giving birth to different coloured albinos, so he concluded that Adam and Eve were originally white and that Caucasians could give birth to different coloured races. Boyle also extended the theories of Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

about colour and light via optical projection (in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

) into discourses of polygenesis, speculating that maybe these differences were due to "seminal

Seminal, ultimately from Latin ''semen'', "seed", may refer to:

*Relating to seeds

*Relating to semen

*(Of a work, event, or person) Having much social influence

Social influence comprises the ways in which individuals adjust their behavior to me ...

impressions". Taking this into account, it might be considered that he envisioned a good explanation for complexion at his time, due to the fact that now we know that skin colour is disposed by genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

, which are actually contained in the semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen i ...

. Boyle's writings mention that at his time, for "European Eyes", beauty was not measured so much in colour of skin, but in "stature, comely symmetry of the parts of the body, and good features in the face". Various members of the scientific community rejected his views and described them as "disturbing" or "amusing".

In his will, Boyle provided money for a series of lectures to defend the Christian religion

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popul ...

against those he considered "notorious infidels, namely atheists, deists, pagans Pagans may refer to:

* Paganism, a group of pre-Christian religions practiced in the Roman Empire

* Modern Paganism, a group of contemporary religious practices

* Order of the Vine, a druidic faction in the ''Thief'' video game series

* Pagan's ...

, Jews and Muslims", with the provision that controversies between Christians were not to be mentioned (see Boyle Lectures

The Boyle Lectures are named after Robert Boyle, a prominent natural philosopher of the 17th century and son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Under the terms of his Will, Robert Boyle endowed a series of lectures or sermons (originally eight e ...

).

Awards and honours

As a founder of the Royal Society, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1663. Boyle's law is named in his honour. The

As a founder of the Royal Society, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1663. Boyle's law is named in his honour. The Royal Society of Chemistry

The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) is a learned society (professional association) in the United Kingdom with the goal of "advancing the chemistry, chemical sciences". It was formed in 1980 from the amalgamation of the Chemical Society, the Ro ...

issues a Robert Boyle Prize for Analytical Science, named in his honour. The Boyle Medal for Scientific Excellence in Ireland, inaugurated in 1899, is awarded jointly by the Royal Dublin Society

The Royal Dublin Society (RDS) ( ga, Cumann Ríoga Bhaile Átha Cliath) is an Irish philanthropic organisation and members club which was founded as the 'Dublin Society' on 25 June 1731 with the aim to see Ireland thrive culturally and economi ...

and The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

. Launched in 2012, The Robert Boyle Summer School organized by the Waterford Institute of Technology with support from Lismore Castle, is held annually to honor the heritage of Robert Boyle.

Important works

The following are some of the more important of his works:

* 1660 – ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects''

* 1661 – ''

The following are some of the more important of his works:

* 1660 – ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects''

* 1661 – ''The Sceptical Chymist

''The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes'' is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the ''Sceptical Chymist'' presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of corp ...

''

* 1662 – Whereunto is Added a Defence of the Authors Explication of the Experiments, Against the Obiections of Franciscus Linus and Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

(a book-length addendum to the second edition of ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical'')

* 1663 – ''Considerations touching the Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy'' (followed by a second part in 1671)

* 1664 – ''Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours, with Observations on a Diamond that Shines in the Dark''

* 1665 – ''New Experiments and Observations upon Cold''

* 1666 – ''Hydrostatical Paradoxes''Cf. Hunter (2009), p. 147. "It forms a kind of sequel to ''Spring of the Air'' ... but although Boyle notes he might have published it as part of an appendix to that work, it formed a self-contained whole, dealing with atmospheric pressure with particular reference to liquid masses"

* 1666 – ''Origin of Forms and Qualities according to the Corpuscular Philosophy''. (A continuation of his work on the spring of air demonstrated that a reduction in ambient pressure could lead to bubble formation in living tissue. This description of a viper

The Viperidae (vipers) are a family of snakes found in most parts of the world, except for Antarctica, Australia, Hawaii, Madagascar, and various other isolated islands. They are venomous and have long (relative to non-vipers), hinged fangs tha ...

in a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

was the first recorded description of decompression sickness.)

* 1669 – ''A Continuation of New Experiments Physico-mechanical, Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air, and Their Effects''

* 1670 – ''Tracts about the Cosmical Qualities of Things, the Temperature of the Subterraneal and Submarine Regions, the Bottom of the Sea, &tc. with an Introduction to the History of Particular Qualities''

* 1672 – ''Origin and Virtues of Gems''

* 1673 – Essays of the Strange Subtilty, Great Efficacy, Determinate Nature of Effluviums

* 1674 – Two volumes of tracts on the Saltiness of the Sea, Suspicions about the Hidden Realities of the Air, Cold, Celestial Magnets

* 1674 – ''Animadversions upon Mr. Hobbes's Problemata de Vacuo''

* 1676 – Experiments and Notes about the Mechanical Origin or Production of Particular Qualities, including some notes on electricity and magnetism

* 1678 – ''Observations upon an artificial Substance that Shines without any Preceding Illustration''

* 1680 – ''The Aerial Noctiluca''

* 1682 – New Experiments and Observations upon the Icy Noctiluca (a further continuation of his work on the air)

* 1684 – ''Memoirs for the Natural History of the Human Blood''

* 1685 – Short Memoirs for the Natural Experimental History of Mineral Waters

* 1686 – ''A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature''

* 1690 – ''Medicina Hydrostatica''

* 1691 – ''Experimenta et Observationes Physicae''

Among his religious and philosophical writings were:

* 1648/1660 – ''Seraphic Love'', written in 1648, but not published until 1660

* 1663 – ''Some Considerations Touching the Style of the H'' 'oly''''Scriptures''

* 1664 – ''Excellence of Theology compared with Natural Philosophy''

* 1665 – Occasional Reflections upon Several Subjects, which was ridiculed by Swift in Meditation Upon a Broomstick, and by Butler

A butler is a person who works in a house serving and is a domestic worker in a large household. In great houses, the household is sometimes divided into departments with the butler in charge of the dining room, wine cellar, and pantry. Some a ...

in An Occasional Reflection on Dr Charlton's Feeling a Dog's Pulse at Gresham College

* 1675 – Some Considerations about the Reconcileableness of Reason and Religion, with a Discourse about the Possibility of the Resurrection

* 1687 – ''The Martyrdom of Theodora, and of Didymus''

* 1690 – ''The Christian Virtuoso

''The Christian Virtuoso'' (1690) was one of the last books published by Robert Boyle, who was a champion of his Anglican faith. This book summarised his religious views including his idea of a clock-work universe created by God.

Boyle was a devo ...

''

See also

*, phosphorus manufacturer who started as Boyle's assistant *, history section *, one of Boyle's theological works *, a painting of a demonstration of one of Boyle's experiments *, thermodynamic quantity named after Boyle * * * * * * *References

Further reading

* M. A. Stewart (ed.), ''Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle'', Indianapolis: Hackett, 1991. * Fulton, John F., ''A Bibliography of the Honourable Robert Boyle, Fellow of the Royal Society''. Second edition. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1961. * Hunter, Michael, ''Boyle : Between God and Science'', New Haven : Yale University Press, 2009. * Hunter, Michael''Robert Boyle, 1627–91: Scrupulosity and Science''

The Boydell Press, 2000 * Principe, Lawrence

''The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest''

Princeton University Press, 1998 * Shapin, Stephen; Schaffer, Simon, '' Leviathan and the Air-Pump.'' * Ben-Zaken, Avner, "Exploring the Self, Experimenting Nature", i

''Reading Hayy Ibn-Yaqzan: A Cross-Cultural History of Autodidacticism''

(Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), pp. 101–126. ;Boyle's published works online

''The Sceptical Chymist''

– Project Gutenberg

''Essay on the Virtue of Gems''

– Gem and Diamond Foundation

''Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours''

– Gem and Diamond Foundation

''Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours''

– Project Gutenberg

University of London

''Hydrostatical Paradoxes''

– Google Books

External links

Robert Boyle

''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' *

Readable versions of Excellence of the mechanical hypothesis, Excellence of theology, and Origin of forms and qualities

Robert Boyle Project, Birkbeck, University of London

* ttp://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1997/PSCF3-97Woodall.html The Relationship between Science and Scripture in the Thought of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest : Including Boyle's "Lost" Dialogue on the Transmutation of Metals

Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial su ...

, 1998,

* Robert Boyle's (1690''Experimenta et considerationes de coloribus''

– digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Boyle, Robert 1627 births Irish Anglicans 1691 deaths 17th-century Anglo-Irish people Discoverers of chemical elements English alchemists 17th-century English chemists English physicists Founder Fellows of the Royal Society Independent scientists Irish alchemists Irish chemists Irish physicists People educated at Eton College People from Lismore, County Waterford Philosophers of science

Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

Younger sons of earls

17th-century English writers

17th-century English male writers

17th-century Irish writers

17th-century Irish philosophers

17th-century English philosophers

Fluid dynamicists

17th-century alchemists

Writers about religion and science