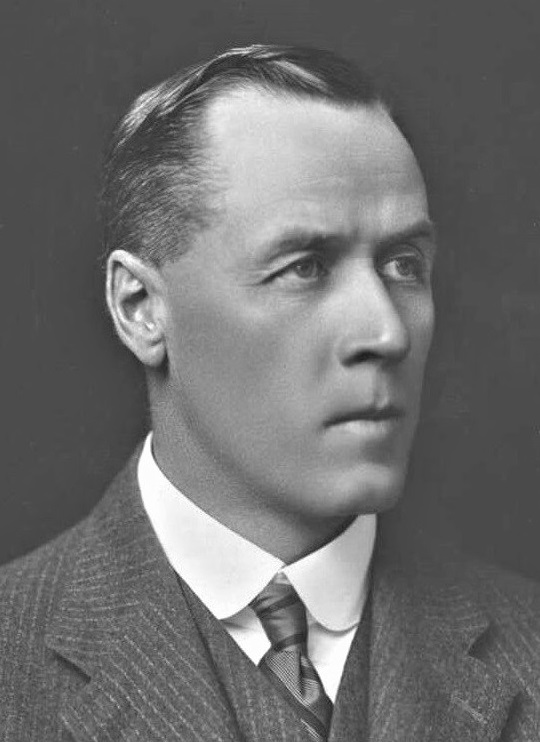

Sir John Latham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Greig Latham

Latham had a distinguished legal career. He was admitted to the

Latham had a distinguished legal career. He was admitted to the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

GCMG

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

QC (26 August 1877 – 25 July 1964) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the fifth Chief Justice of Australia

The Chief Justice of Australia is the presiding Justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia. The incumbent is Susan Kiefel, who is the first woman to hold the position.

Co ...

, in office from 1935 to 1952. He had earlier served as Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-GeneralThe title is officially "Attorney-General". For the purposes of distinguishing the office from other attorneys-general, and in accordance with usual practice in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions, the Aust ...

under Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, as leader of the Nationalist Party.

Born ...

and Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office, 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He ...

, and was Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

from 1929 to 1931 as the final leader of the Nationalist Party.

Latham was born in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

. He studied arts and law at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, and was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1904. He soon became one of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

's best known barristers. In 1917, Latham joined the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

as the head of its intelligence division. He served on the Australian delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Pressburg (now Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY ''Iolaire'' sinks off the c ...

, where he came into conflict with Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

. At the 1922 federal election, Latham was elected to parliament as an independent on an anti-Hughes platform. He got on better with Hughes' successor Stanley Bruce, and formally joined the Nationalist Party in 1925, subsequently winning promotion to cabinet as Attorney-General. He was also Minister for Industry from 1928, and was one of the architects of the unpopular industrial relations policy that contributed to the government's defeat at the 1929 election. Bruce lost his seat, and Latham was reluctantly persuaded to become Leader of the Opposition.

In 1931, Latham led the Nationalists into the new United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

, joining with Joseph Lyons and other disaffected Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

MPs. Despite the Nationalists forming a larger proportion of the new party, he relinquished the leadership to Lyons, a better campaigner, thus becoming the first opposition leader to fail to contest a general election. In the Lyons Government, Latham was the ''de facto'' deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

, serving both as Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

. He retired from politics in 1934, and the following year was appointed to the High Court as Chief Justice. From 1940 to 1941, Latham took a leave of absence from the court to become the inaugural Australian Ambassador to Japan

The Ambassador of Australia to Japan is an officer of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the head of the Embassy of the Commonwealth of Australia to Japan. The position has the rank and status of an Ambassador Extraordin ...

. He left office in 1952 after almost 17 years as Chief Justice; only Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

has served for longer.

Early life and education

Latham was born inAscot Vale

Ascot Vale is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, north-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Moonee Valley local government area. Ascot Vale recorded a population of 15,197 at the 2021 c ...

, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. His father was a prominent citizen, whose achievements as secretary for the Society for the Protection of Animals were deeply respected. John Latham won a scholarship and became a successful student at Scotch College and the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, studying logic, philosophy and law. At one point, he was the recipient of the Supreme Court Judges' Prize. In November 1902, Latham became the first secretary of the Boobook Society (named for the southern boobook

The Australian boobook (''Ninox boobook''), which is known in some regions as the mopoke, is a species of owl native to mainland Australia, southern New Guinea, the island of Timor, and the Sunda Islands. Described by John Latham in 1801, it w ...

owl), a group of Melbourne academics and professionals which still meets.

Career

Naval career

During World War I, he was an intelligence officer in theRoyal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

, holding the rank of lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

. He was the head of Naval Intelligence from 1917, and was part of the Australian delegation to the Imperial Conference and then the Versailles Peace Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, for which he was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, George III, King George III.

...

(CMG) in the 1920 New Year Honours. He grew to dislike Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

.

Legal career

Latham had a distinguished legal career. He was admitted to the

Latham had a distinguished legal career. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar

The Victorian Bar is the bar association of the Australian State of Victoria. The current President of the Bar is Roisin Annesley KC. Its members are barristers registered to practice in Victoria. On 30 June 2020, there were 2,179 counsels ...

in 1904, and was made a King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

in 1922. In 1920, Latham appeared before the High Court representing the State of Victoria

Victoria is a state in southeastern Australia. It is the second-smallest state with a land area of , the second most populated state (after New South Wales) with a population of over 6.5 million, and the most densely populated state in Au ...

in the famous Engineers' case

''Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd'', commonly known as the ''Engineers case'', . was a landmark decision by the High Court of Australia on 31 August 1920. The immediate issue concerned the Commonwealth's power under ...

, alongside such people as Dr H.V. Evatt and Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

.

Political career

In 1922, Latham was elected to theAustralian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of the ...

for Kooyong in eastern Melbourne. Although his philosophy was close to Hughes' Nationalist Party, Latham's experience of Hughes in Europe ensured that he would not serve under him in a Parliament. Instead, he initially aligned himself with the Liberal Union, a group of conservatives opposed to Hughes; his campaign slogan was 'Get Rid of Hughes'. On Hughes' removal in 1923, he subsequently joined the Nationalist Party (though he officially remained a Liberal until 1925). From 1925 to 1929, he served as the Commonwealth Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

in the Bruce–Page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young mal ...

government. He wrote several books, including ''Australia and the British Empire'' in which he argued for Australia's place in the British Empire.

After Bruce lost his Parliamentary seat in 1929, Latham was elected as leader of the Nationalist Party, and hence Leader of the Opposition. He opposed the ratification of the Statute of Westminster (1931) and worked very hard to prevent it.

Two years later, Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office, 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He ...

led defectors from the Labor Party across the floor and merged them with the Nationalists to form the United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

. Although the new party was dominated by former Nationalists, Latham agreed to become Deputy Leader of the Opposition under Lyons. It was believed having a former Labor man at the helm would present an image of national unity in the face of the economic crisis. Additionally, the affable Lyons was seen as much more electorally appealing than the aloof Latham, especially given that the UAP's primary goal was to win over natural Labor constituencies to what was still, at bottom, an upper- and middle-class conservative party. Future ALP leader Arthur Calwell

Arthur Augustus Calwell (28 August 1896 – 8 July 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Labor Party from 1960 to 1967. He led the party to three federal elections.

Calwell grew up in Melbourne and attended St J ...

wrote in his autobiography, ''Be Just and Fear Not,'' that by standing aside in favour of Lyons, Latham knew he was giving up a chance to become Prime Minister.

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

and (unofficially) the Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

. Latham held these positions until 1934, when he retired from the Commonwealth Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-g ...

. He was succeeded as member for Kooyong, Attorney-General and Minister of Industry by Menzies, who would go on to become Australia's longest-serving Prime Minister.

Latham became the first former Opposition Leader, who did not become Prime Minister, to become a minister.

He was the only person to hold this distinction until Bill Hayden in 1983.

Judicial career

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises Original jurisdiction, original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Constitution of Australia, Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established fol ...

on 11 October 1935. From 1940 to 1941, he took leave from the Court and travelled to Tokyo to serve as Australia's first Minister to Japan. He retired from the High Court in April 1952, after a then-record 16 years in office.

As Chief Justice, Latham corresponded with political figures to an extent later writers have viewed as inappropriate. Latham offered advice on political matters – frequently unsolicited – to several prime ministers and other senior government figures. During World War II, he made a number of suggestions about defence and foreign policy, and provided John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He led the country for the majority of World War II, including all but the last few ...

with a list of constitutional amendments he believed should be made to increase the federal government's power. Towards the end of his tenure, Latham's correspondence increasingly revealed his personal views on major political issues that had previously come before the court; namely, opposition to the Chifley Government's health policies and support of the Menzies Government

Menzies is a Scottish surname, with Gaelic forms being Méinnearach and Méinn, and other variant forms being Menigees, Mennes, Mengzes, Menzeys, Mengies, and Minges.

Derivation and history

The name and its Gaelic form are probably derived f ...

's attempt to ban the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

. He advised Earle Page on how the government could amend the constitution to legally ban the Communist Party, and corresponded with his friend Richard Casey on ways to improve the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

's platform.

According to Fiona Wheeler, there was no direct evidence that Latham's political views interfered with his judicial reasoning, but "the mere appearance of partiality is enough for concern" and could have been difficult to refute if uncovered. She particularly singles out his correspondence with Casey as "an extraordinary display of political partisanship by a serving judge." Although Latham emphasised the need for secrecy to the recipients of his letters, he retained copies of most of them in his personal papers, apparently unconcerned that they could be discovered and analysed after his death. He rationalised his actions as those of a private individual, separate from his official position, and maintained a "Janus-like divide between his public and private persona". In other fora he took pains to demonstrate his independence, rejecting speaking engagements if he believed they could be construed as political statements. Nonetheless, "many instances of Latham's advising ..would today be regarded as clear affronts to basic standards of judicial independence Judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent from the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan inte ...

and propriety".

Latham was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

, Richard O'Connor

General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, and commanded the Western Desert Force in the early years of the Second World War. He ...

, Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

, H. B. Higgins

Henry Bournes Higgins KC (30 June 1851 – 13 January 1929) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge. He served on the High Court of Australia from 1906 until his death in 1929, after briefly serving as Attorney-General of Australia in ...

, Edward McTiernan

Sir Edward Aloysius McTiernan, KBE (16 February 1892 – 9 January 1990), was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge. He served on the High Court of Australia from 1930 to 1976, the longest-serving judge in the court's history.

McTiernan ...

, Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

, and Lionel Murphy

Lionel Keith Murphy QC (30 August 1922 – 21 October 1986) was an Australian politician, barrister, and judge. He was a Senator for New South Wales from 1962 to 1975, serving as Attorney-General in the Whitlam Government, and then sat on the ...

.

Personal life

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist, after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on the 18th May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote. Latham married Eleanor Mary Tobin, known as Ella. They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb ofRichmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of ''The Trident'', a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch

Sir Walter Logie Forbes Murdoch, (17 September 187430 July 1970) was a prominent Australian academic and essayist famous for his intelligence and wit. He was a founding professor of English and former Chancellor of the University of Western A ...

. The board also included poet Bernard O'Dowd

Bernard Patrick O'Dowd (11 April 1866 – 1 September 1953) was an Australian poet, activist, lawyer, and journalist. He worked for the Victorian colonial and state governments for almost 50 years, first as an assistant librarian at the Supreme ...

.

Latham was president of the Free Library Movement of Victoria from 1937 and served as president of the Library Association of Australia

The Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA), formerly the Australian Institute of Librarians and Library Association of Australia, is the peak professional organisation for the Australian library and information services sector. F ...

from 1950 to 1953. He was the first non-librarian to hold the position.

Legacy

TheCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

suburb of Latham was named after him in 1971. There is also a lecture theatre named after him at The University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Latham, John 1877 births 1964 deaths Lawyers from Melbourne Ambassadors of Australia to Japan Attorneys-General of Australia Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Melbourne Law School alumni Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia United Australia Party members of the Parliament of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Kooyong Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Royal Australian Navy officers Australian military personnel of World War I Chief justices of Australia Justices of the High Court of Australia People educated at Scotch College, Melbourne Australian lacrosse players Australian King's Counsel Australian atheists Judges from Melbourne Liberal Party (1922) members of the Parliament of Australia Leaders of the Nationalist Party of Australia 20th-century Australian politicians Former Methodists Australian former Christians People from Ascot Vale, Victoria