Sir Francis Walsingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

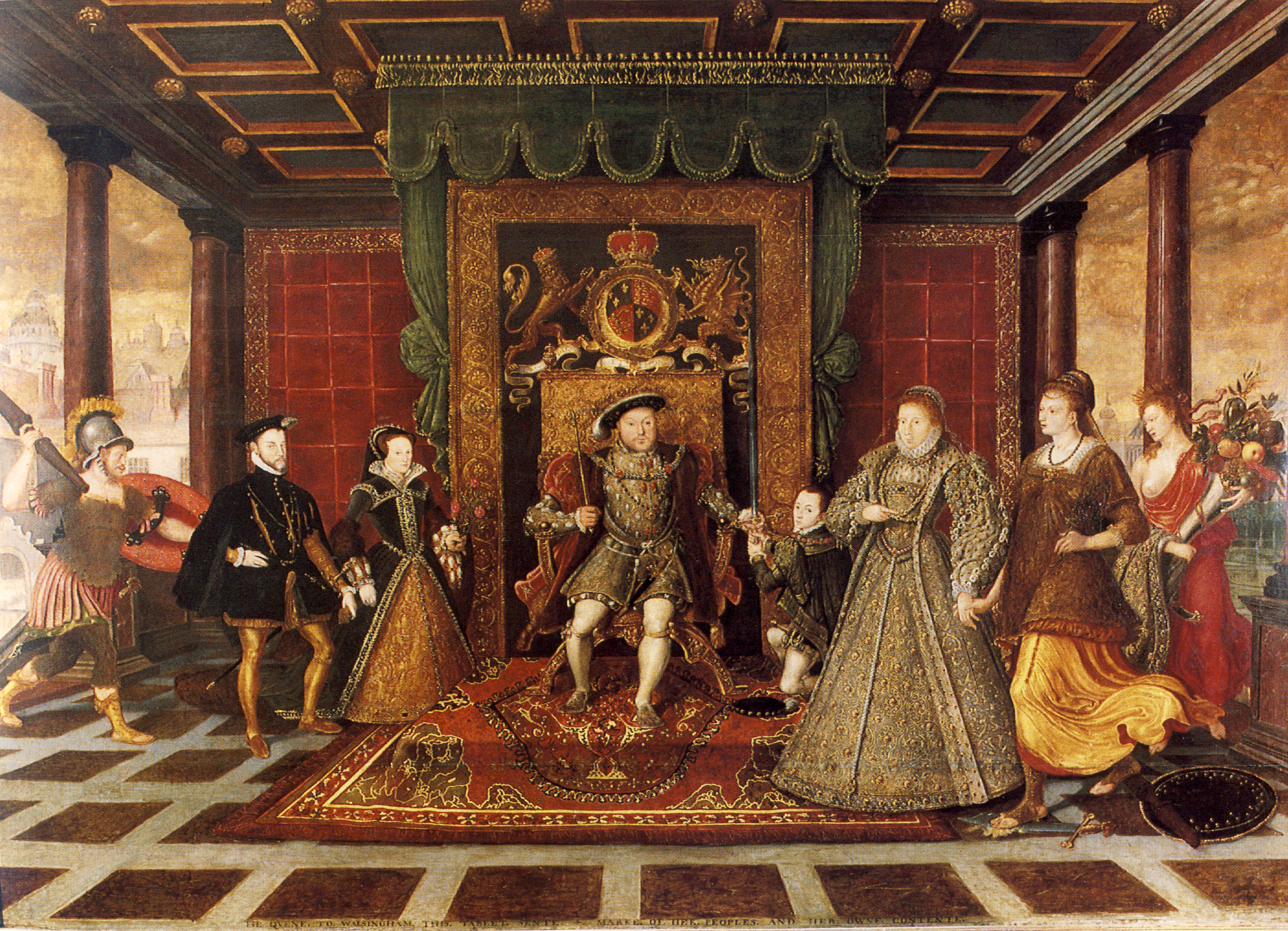

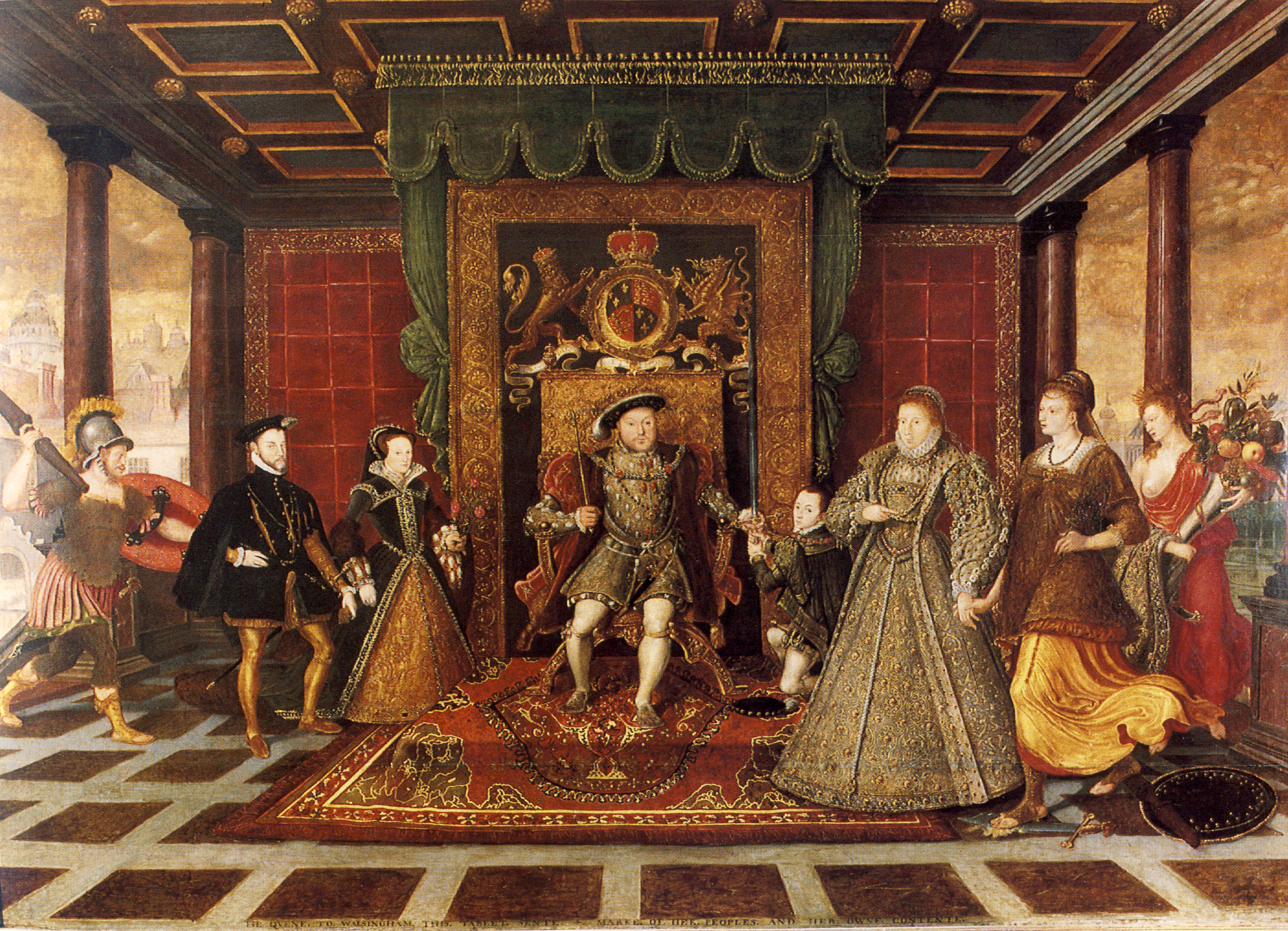

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Walsingham attended Cambridge University and travelled in continental Europe before embarking on a career in law at the age of twenty. A committed Protestant, during the reign of the Catholic Queen

Francis Walsingham was born around 1532, probably at Foots Cray, near

Francis Walsingham was born around 1532, probably at Foots Cray, near

In his will, dated 12 December 1589, Walsingham complained of "the greatness of my debts and the mean state shall leave my wife and heirs in",Hutchinson, p. 253 but the true state of his finances is unclear.Hutchinson, p. 257 He received grants of land from the Queen, grants for the export of cloth and leases of customs in the northern and western ports. His primary residences, apart from the court, were in Seething Lane by the Tower of London (now the site of a Victorian office building called Walsingham House), at Barn Elms in

In his will, dated 12 December 1589, Walsingham complained of "the greatness of my debts and the mean state shall leave my wife and heirs in",Hutchinson, p. 253 but the true state of his finances is unclear.Hutchinson, p. 257 He received grants of land from the Queen, grants for the export of cloth and leases of customs in the northern and western ports. His primary residences, apart from the court, were in Seething Lane by the Tower of London (now the site of a Victorian office building called Walsingham House), at Barn Elms in

Walsingham, Sir Francis (c. 1532–1590)

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online ed. May 2009, (subscription required) * Cooper, John (2011). ''The Queen's Agent: Francis Walsingham at the Court of Elizabeth I''. London: Faber & Faber. . * Fraser, Antonia (1994) 969 ''Mary Queen of Scots''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. . * Hasler, P. W. (1981).

Walsingham, Francis (c. 1532–90), of Scadbury and Foots Cray, Kent; Barn Elms, Surr. and Seething Lane, London

, ''History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603''. * Hutchinson, Robert (2007). ''Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the Secret War that Saved England''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. . * Latham, Bethany (2011).

Elizabeth I in Film and Television: A Study of the Major Portrayals

'. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. . * Parker, Geoffrey (2000). ''The Grand Strategy of Philip II''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. . * Rozett, Martha Tuck (2003).

Constructing a World: Shakespeare's England and the New Historical Fiction

'. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. . * Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2012). ''Western Civilization: Since 1500''. Eighth edition. Boston: Wadsworth. . * Wilson, Derek (2007). ''Sir Francis Walsingham: A Courtier in an Age of Terror''. New York: Carroll & Graf. .

Her Majesty's Spymaster: Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the Birth of Modern Espionage

'. New York: Viking. . * Haynes, Alan (2004). ''Walsingham: Elizabethan Spymaster & Statesman''. Stroud, Glos.: Sutton. . * Hutchinson, John (1892). Sir Francis Walsingham". ''Men of Kent and Kentishmen''. Canterbury: Cross & Jackman. pp. 140–141. * * * * Read, Conyers (1925). ''Mr Secretary Walsingham and the Policy of Queen Elizabeth''. Oxford: Clarendon Press (an exhaustive three-volume biography that is still valuable despite its age). Via the Internet Archive

Volume 1

Volume 2

, an

Volume 3

.

Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

he joined other expatriates in exile in Switzerland and northern Italy until Mary's death and the accession of her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth.

Walsingham rose from relative obscurity to become one of the small coterie who directed the Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

state, overseeing foreign, domestic and religious policy. He served as English ambassador to France

The ambassador of the Kingdom of England to France (French: l'ambassadeur anglais en France) was the foremost diplomatic representative of the historic Kingdom of England in France, before the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707.

...

in the early 1570s and witnessed the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (french: Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French War ...

. As principal secretary, he supported exploration, colonization, the use of England's maritime strength and the plantation of Ireland. He worked to bring Scotland and England together. Overall, his foreign policy demonstrated a new understanding of the role of England as a maritime Protestant power with intercontinental trading ties. He oversaw operations that penetrated Spanish military preparation, gathered intelligence from across Europe, disrupted a range of plots against Elizabeth and secured the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Origins and early life

Francis Walsingham was born around 1532, probably at Foots Cray, near

Francis Walsingham was born around 1532, probably at Foots Cray, near Chislehurst

Chislehurst () is a suburban district of south-east London, England, in the London Borough of Bromley. It lies east of Bromley, south-west of Sidcup and north-west of Orpington, south-east of Charing Cross. Before the creation of Greater L ...

in Kent, the only son of William Walsingham (died 1534), a successful and well-connected London lawyer who served as a member of the commission appointed to investigate the estates of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in 1530.Hutchinson, p. 28 William's elder brother was Sir Edmund Walsingham, Lieutenant of the Tower of London.

Francis's mother was Joyce Denny, a daughter of the courtier Sir Edmund Denny of Cheshunt in Hertfordshire, and a sister of the courtier Sir Anthony Denny, the principal Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. After the death of her first husband she married the courtier Sir John Carey in 1538. Carey's brother William was the husband of Mary Boleyn

Mary Boleyn, also known as Lady Mary, (c. 1499 – 19 July 1543) was the sister of English queen consort Anne Boleyn, whose family enjoyed considerable influence during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Mary was one of the mistresses of Henry VII ...

, the elder sister of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII.

Of Francis's five sisters, Mary married Sir Walter Mildmay, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

for over 20 years, and Elizabeth married the parliamentarian Peter Wentworth.

Francis Walsingham matriculated at King's College, Cambridge, in 1548 with many other Protestants but as an undergraduate of high social status did not sit for a degree. From 1550 or 1551, he travelled in continental Europe, returning to England by 1552 to enrol at Gray's Inn, one of the qualifying bodies for English lawyers.

Upon the death in 1553 of Henry VIII's successor, Edward VI, Edward's Catholic half-sister Mary became queen. Many wealthy Protestants, such as John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

and John Cheke, fled England, and Walsingham was among them. He continued his studies in law at the universities of Basel and Padua, where he was elected to the governing body by his fellow students in 1555.

Rise to power

Mary I died in May 1558 and was succeeded by her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth. Walsingham returned to England and through the support of one of his fellow former exiles,Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford

Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, KG ( – 28 July 1585) of Chenies in Buckinghamshire and of Bedford House in Exeter, Devon, was an English nobleman, soldier, and politician. He was a godfather to the Devon-born sailor Sir Francis Drake ...

, he was elected to Elizabeth's first parliament as the member for Bossiney, Cornwall, in 1559. At the subsequent election in 1563, he was returned for both Lyme Regis, Dorset, another constituency under Bedford's influence, and Banbury, Oxfordshire

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshire ...

. He chose to sit for Lyme Regis. In January 1562 he married Anne, daughter of Sir George Barne, Lord Mayor of London in 1552–3, and widow of wine merchant Alexander Carleill. Anne died two years later leaving her son Christopher Carleill in Walsingham's care. In 1566, Walsingham married Ursula St. Barbe

Ursula St Barbe (died 18 June 1602), also known as Ursula, Lady Worsley and Ursula, Lady Walsingham, was a lady at the court of Queen Elizabeth I of England.

She was the daughter of Henry St Barbe, of Ashington, Somerset, by his wife, Eleanor L ...

, widow of Sir Richard Worsley, and Walsingham acquired her estates of Appuldurcombe

Appuldurcombe House (also spelt Appledorecombe or Appledore Combe) is the shell of a large 18th-century English Baroque country house of the Worsley family. The house is situated near to Wroxall on the Isle of Wight, England. It is now managed b ...

and Carisbrooke Priory

Carisbrooke Priory was an alien priory, a dependency of Lyre Abbey in Normandy. The priory was situated on rising ground on the outskirts of Carisbrooke close to Newport on the Isle of Wight. This priory was dissolved in around 1415.

A second ...

on the Isle of Wight. The following year, she bore him a daughter, Frances. Walsingham's other two stepsons, Ursula's sons John and George, were killed in a gunpowder accident at Appuldurcombe in 1567.

In the following years, Walsingham became active in soliciting support for the Huguenots in France and developed a friendly and close working relationship with Nicholas Throckmorton, his predecessor as MP for Lyme Regis and a former ambassador to France. By 1569, Walsingham was working with William Cecil to counteract plots against Elizabeth. He was instrumental in the collapse of the Ridolfi plot, which hoped to replace Elizabeth with the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots. He is credited with writing propaganda decrying a conspiratorial marriage between Mary and Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, and Roberto di Ridolfi, after whom the plot was named, was interrogated at Walsingham's house.

In 1570, the Queen chose Walsingham to support the Huguenots in their negotiations with Charles IX of France. Later that year, he succeeded Sir Henry Norris as English ambassador in Paris. One of his duties was to continue negotiations for a marriage between Elizabeth and Charles IX's younger brother Henry, Duke of Anjou

Henry III (french: Henri III, né Alexandre Édouard; pl, Henryk Walezy; lt, Henrikas Valua; 19 September 1551 – 2 August 1589) was King of France from 1574 until his assassination in 1589, as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Li ...

. The marriage plan was eventually dropped on the grounds of Henry's Catholicism. A substitute match with the youngest brother, Francis, Duke of Alençon

''Monsieur'' Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (french: Hercule François; 18 March 1555 – 10 June 1584) was the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early years

He was scarred by smallpox at age eight, an ...

, was proposed but Walsingham considered him ugly and "void of a good humour". Elizabeth was 20 years older than Alençon, and was concerned that the age difference would be seen as absurd. Walsingham believed that it would serve England better to seek a military alliance with France against Spanish interests. The defensive Treaty of Blois was concluded between France and England in 1572, but the treaty made no provision for a royal marriage and left the question of Elizabeth's successor open.

The Huguenots and other European Protestant interests supported the nascent revolt in the Spanish Netherlands, which were provinces of Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

. When Catholic opposition to this course in France resulted in the death of Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny

Gaspard de Coligny may refer to:

*Gaspard I de Coligny Gaspard I de Coligny, Count of Coligny, seigneur de Châtillon (1465/1470–1522), known as the Marshal of Châtillon, was a French soldier.

He was born in Châtillon-Coligny, the second son ...

and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (french: Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French War ...

, Walsingham's house in Paris became a temporary sanctuary for Protestant refugees, including Philip Sidney. Ursula, who was pregnant, escaped to England with their four-year-old daughter. She gave birth to a second girl, Mary, in January 1573 while Walsingham was still in France. He returned to England in April 1573, having established himself as a competent official whom the Queen and Cecil could trust. He cultivated contacts throughout Europe, and a century later his dispatches would be published as ''The Complete Ambassador''.

In the December following his return, Walsingham was appointed to the Privy Council of England

The Privy Council of England, also known as His (or Her) Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (), was a body of advisers to the sovereign of the Kingdom of England. Its members were often senior members of the House of Lords and the House of ...

and was made joint principal secretary (the position which later became "Secretary of State") with Sir Thomas Smith. Smith retired in 1576, leaving Walsingham in effective control of the privy seal

A privy seal refers to the personal seal of a reigning monarch, used for the purpose of authenticating official documents of a much more personal nature. This is in contrast with that of a great seal, which is used for documents of greater impor ...

, though he was not formally invested as Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

. Walsingham acquired a Surrey county seat in Parliament from 1572 that he retained until his death, but he was not a major parliamentarian. He was knighted on 1 December 1577, and held the sinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is an office, carrying a salary or otherwise generating income, that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval chu ...

posts of Recorder of Colchester, '' custos rotulorum'' of Hampshire, and High Steward of Salisbury, Ipswich and Winchester. He was appointed Chancellor of the Order of the Garter The Chancellor of the Order of the Garter is an officer of the Order of the Garter.

History of the office

When the Order of the Garter was founded in 1348 at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, by Edward III of England three officers were initiall ...

from 22 April 1578 until succeeded by Sir Amias Paulet in June 1587, when he became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in addition to principal secretary.

Secretary of State

The duties of the principal secretary were not defined formally, but as he handled all royal correspondence and determined the agenda of council meetings, he could wield great influence in all matters of policy and in every field of government, both foreign and domestic. During his term of office, Walsingham supported the use of England's maritime power to open new trade routes and explore the New World, and was at the heart of international affairs. He was involved directly with English policy towards Spain, the Netherlands, Scotland, Ireland and France, and embarked on several diplomatic missions to neighbouring European states. Closely linked to the mercantile community, he actively supported trade promotion schemes and invested in theMuscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company russian: Московская компания, Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint ...

and the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, ...

. He supported the attempts of John Davis and Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canada ...

to discover the Northwest Passage and exploit the mineral resources of Labrador, and encouraged Humphrey Gilbert's exploration of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. Gilbert's voyage was largely financed by recusant Catholics and Walsingham favoured the scheme as a potential means of removing Catholics from England by encouraging emigration to the New World. Walsingham was among the promoters of Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

's profitable 1578–1581 circumnavigation of the world, correctly judging that Spanish possessions in the Pacific were vulnerable to attack. The venture was calculated to promote the Protestant interest by embarrassing and weakening the Spanish, as well as to seize Spanish treasure. The first edition of Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

's ''Principal Navigation, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation'' was dedicated to Walsingham.

Walsingham advocated direct intervention in the Netherlands in support of the Protestant revolt against Spain, on the grounds that although wars of conquest were unjust, wars in defence of religious liberty and freedom were not. Cecil was more circumspect and advised a policy of mediation, a policy that Elizabeth endorsed. Walsingham was sent on a special embassy to the Netherlands in 1578, to sound out a potential peace deal and gather military intelligence.

Charles IX died in 1574 and the Duke of Anjou inherited the French throne as Henry III. Between 1578 and 1581 the Queen resurrected attempts to negotiate a marriage with Henry III's youngest brother, the Duke of Alençon, who had put himself forward as a protector of the Huguenots and a potential leader of the Dutch. Walsingham was sent to France in mid-1581 to discuss an Anglo-French alliance, but the French wanted the marriage agreed first and Walsingham was under instruction to obtain a treaty before committing to the marriage. He returned to England without an agreement. Personally, Walsingham opposed the marriage, perhaps to the point of encouraging public opposition. Alençon was a Catholic and as his elder brother, Henry III, was childless, he was heir presumptive to the French throne. Elizabeth was past the age of childbearing and had no clear successor. If she died while married to him, her realms could fall under French control. By comparing the match of Elizabeth and Alençon with the match of the Protestant Henry of Navarre and the Catholic Margaret of Valois, which occurred in the week before the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (french: Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French War ...

, the "most horrible spectacle" he had ever witnessed, Walsingham raised the spectre of religious riots in England in the event of the marriage proceeding. Elizabeth put up with his blunt, often unwelcome, advice, and acknowledged his strong beliefs in a letter, in which she called him "her Moor hocannot change his colour".

These were years of tension in policy towards France, with Walsingham sceptical of the unpredictable Henry III and distrustful of the English ambassador in Paris, Edward Stafford Edward Stafford may refer to:

People

* Edward Stafford, 2nd Earl of Wiltshire (1470–1498)

*Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (1478–1521), executed for treason

*Edward Stafford, 3rd Baron Stafford (1535–1603)

*Sir Edward Stafford (diplo ...

. Stafford, who was compromised by his gambling debts, was in the pay of the Spanish and passed vital information to Spain. Walsingham may have been aware of Stafford's duplicity, as he fed the ambassador false information, presumably in the hope of fooling or confusing the Spanish.

The pro-English Regent of Scotland James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, whom Walsingham had supported, was overthrown in 1578. After the collapse of the Raid of Ruthven, another initiative to secure a pro-English government in Scotland, Walsingham reluctantly visited the Scottish court in August 1583, knowing that his diplomatic mission was unlikely to succeed. James VI dismissed Walsingham's advice on domestic policy saying he was an "absolute King" in Scotland. Walsingham replied with a discourse on the topic that "young princes were many times carried into great errors upon an opinion of the absoluteness of their royal authority and do not consider, that when they transgress the bounds and limits of the law, they leave to be kings and become tyrants." According to James Melville of Halhill, James VI intended to give Walsingham a valuable diamond ring as a parting gift, but James Stewart, Earl of Arran, who Walsingham had ignored, substituted a ring of crystal. A mutual defence pact was eventually agreed in the Treaty of Berwick of 1586.

Walsingham's cousin Edward Denny fought in Ireland during the rebellion of the Earl of Desmond and was one of the English settlers granted land in Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

confiscated from Desmond. Walsingham's stepson Christopher Carleill commanded the garrisons at Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

and Carrickfergus. Walsingham thought Irish farmland was underdeveloped and hoped that plantation would improve the productivity of estates. Tensions between the native Irish and the English settlers had lasting effects on the history of Ireland.

Walsingham's younger daughter Mary died aged seven in July 1580; his elder daughter, Frances, married Sir Philip Sidney on 21 September 1583, despite the Queen's initial objections to the match (for unknown reasons) earlier in the year. As part of the marriage agreement, Walsingham agreed to pay £1,500 of Sidney's debts and gave his daughter and son-in-law the use of his manor at Barn Elms in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

. A granddaughter born in November 1585 was named Elizabeth after the Queen, who was one of two godparents along with Sidney's uncle, Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ov ...

. The following year, Sidney was killed fighting the Spanish in the Netherlands and Walsingham was faced with paying off more of Sidney's extensive debts. His widowed daughter gave birth, in a difficult delivery, to a second child shortly afterward, but the baby, a girl, was stillborn.

Espionage

Walsingham was driven by Protestant zeal to counter Catholicism, and sanctioned the use of torture against Catholic priests and suspected conspirators. Edmund Campion was among those tortured and found guilty on the basis of extracted evidence; he washanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under Edward III of England, King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the rei ...

at Tyburn in 1581. Walsingham could never forget the atrocities against Protestants he had witnessed in France during the Bartholomew's Day massacre and believed a similar slaughter would occur in England in the event of a Catholic resurgence. Walsingham's brother-in-law Robert Beale, who was in Paris with Walsingham at the time of the massacre, encapsulated Walsingham's view: "I think it time and more than time for us to awake out of our dead sleep, and take heed lest like mischief as has already overwhelmed the brethren and neighbours in France and Flanders embrace us which be left in such sort as we shall not be able to escape." Walsingham tracked down Catholic priests in England and supposed conspirators by employing informers, and intercepting correspondence. Walsingham's staff in England included the cryptographer Thomas Phelippes, who was an expert in forgery and deciphering letters, and Arthur Gregory, who was skilled at breaking and repairing seals without detection.

In May 1582, letters from the Spanish ambassador in England, Bernardino de Mendoza, to contacts in Scotland were found on a messenger by Sir John Forster, who forwarded them to Walsingham. The letters indicated a conspiracy among the Catholic powers to invade England and displace Elizabeth with Mary, Queen of Scots. By April 1583, Walsingham had a spy, identified as Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmologic ...

by historian John Bossy, deployed in the French embassy in London. Walsingham's contact reported that Francis Throckmorton

Sir Francis Throckmorton (155410 July 1584) was a conspirator against Queen Elizabeth I of England in the Throckmorton Plot.

Life

He was the son of Sir John Throckmorton, who was the seventh out of eight sons of Sir George Throckmorton of C ...

, a nephew of Walsingham's old friend Nicholas Throckmorton, had visited the ambassador, Michel de Castelnau

Michel de Castelnau, Sieur de la Mauvissière (c. 1520–1592), French soldier and diplomat, ambassador to Queen Elizabeth. His memoirs, covering the period between 1559 and 1570, are considered a more reliable source for the period than many oth ...

. In November 1583, after six months of surveillance, Walsingham had Throckmorton arrested and then tortured to secure a confession—an admission of guilt that clearly implicated Mendoza. The Throckmorton plot called for an invasion of England along with a domestic uprising to liberate Mary, Queen of Scots, and depose Elizabeth. Throckmorton was executed in 1584 and Mendoza was expelled from England.

Entrapment of Mary, Queen of Scots

After the assassination in mid-1584 of William the Silent, the leader of the Dutch revolt against Spain, English military intervention in the Low Countries was agreed in the Treaties of Nonsuch of 1585. The murder of William the Silent also reinforced fears for Queen Elizabeth's safety. Walsingham helped create theBond of Association

The (common) bond of association or common bond is the social connection among the members of credit unions and co-operative banks. Common bonds substitute for collateral in the early stages of financial system development. Like solidarity lend ...

, the signatories of which promised to hunt down and kill anyone who conspired against Elizabeth. The Act for the Surety of the Queen's Person, passed by Parliament in March 1585, set up a legal process for trying any claimant to the throne implicated in plots against the Queen. The following month Mary, Queen of Scots, was placed in the strict custody of Sir Amias Paulet, a friend of Walsingham. At Christmas, she was moved to a moated manor house at Chartley Chartley may refer to:

Places

*Chartley Castle lies in ruins to the north of the village of Stowe-by-Chartley in Staffordshire

* Chartley Moss, a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Staffordshire

* Chartley railway station, former Bri ...

. Walsingham instructed Paulet to open, read and pass to Mary unsealed any letters that she received, and to block any potential route for clandestine correspondence. In a successful attempt to entrap her, Walsingham arranged a single exception: a covert means for Mary's letters to be smuggled in and out of Chartley in a beer keg. Mary was misled into thinking these secret letters were secure, while in reality they were deciphered and read by Walsingham's agents. In July 1586, Anthony Babington

Anthony Babington (24 October 156120 September 1586) was an English gentleman convicted of plotting the assassination of Elizabeth I of England and conspiring with the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, for which he was hanged, drawn and quartered ...

wrote to Mary about an impending plot to free her and kill Elizabeth. Mary's reply was clearly encouraging and sanctioned Babington's plans. Walsingham had Babington and his associates rounded up; fourteen were executed in September 1586. In October, Mary was put on trial under the Act for the Surety of the Queen's Person in front of 36 commissioners, including Walsingham.

During the presentation of evidence against her, Mary broke down and pointed accusingly at Walsingham saying, "all of this is the work of Monsieur de Walsingham for my destruction", to which he replied, "God is my witness that as a private person I have done nothing unworthy of an honest man, and as Secretary of State, nothing unbefitting my duty." Mary was found guilty and the warrant for her execution was drafted, but Elizabeth hesitated to sign it, despite pressure from Walsingham. Walsingham wrote to Paulet urging him to find "some way to shorten the life" of Mary to relieve Elizabeth of the burden, to which Paulet replied indignantly, "God forbid that I should make so foul a shipwreck of my conscience, or leave so great a blot to my poor posterity, to shed blood without law or warrant." Walsingham made arrangements for Mary's execution; Elizabeth signed the warrant on 1 February 1587 and entrusted it to William Davison, who had been appointed as junior Secretary of State in late September 1586. Davison passed the warrant to Cecil and a privy council convened by Cecil without Elizabeth's knowledge agreed to carry out the sentence as soon as was practical. Within a week, Mary was beheaded. On hearing of the execution, Elizabeth claimed not to have sanctioned the action and that she had not meant Davison to part with the warrant. Davison was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Walsingham's share of Elizabeth's displeasure was small because he was absent from court, at home ill, in the weeks just before and after the execution. Davison was eventually released in October 1588, on the orders of Cecil and Walsingham.

Spanish Armada

From 1586, Walsingham received many dispatches from his agents in mercantile communities and foreign courts detailing Spanish preparations for an invasion of England. Walsingham's recruitment of Anthony Standen, a friend of the Tuscan ambassador to Madrid, was an exceptional intelligence triumph and Standen's dispatches were deeply revealing. Walsingham worked to prepare England for a potential war with Spain, in particular by supervising the substantial rebuilding of Dover Harbour, and encouraging a more aggressive strategy. On Walsingham's instructions, the English ambassador in Turkey, William Harborne, attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the Ottoman Sultan to attack Spanish possessions in the Mediterranean in the hope of distracting Spanish forces. Walsingham supportedFrancis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

's raid of Cadiz in 1587, which wrought havoc with Spanish logistics. The Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

sailed for England in July 1588. Walsingham received regular dispatches from the English naval forces, and raised his own troop of 260 men as part of the land defences. On 18 August 1588, after the dispersal of the armada, naval commander Lord Henry Seymour wrote to Walsingham, "you have fought more with your pen than many have in our English navy fought with their enemies".

In foreign intelligence, Walsingham's extensive network of "intelligencers", who passed on general news as well as secrets, spanned Europe and the Mediterranean.Cooper, p. 175; Hutchinson, p. 89 While foreign intelligence was a normal part of the principal secretary's activities, Walsingham brought to it flair and ambition, and large sums of his own money. He cast his net more widely than others had done previously: expanding and exploiting links across the continent as well as in Constantinople and Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

, and building and inserting contacts among Catholic exiles. Among his spies may have been the playwright Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

; Marlowe was in France in the mid-1580s and was acquainted with Walsingham's kinsman Thomas Walsingham

Thomas Walsingham (died c. 1422) was an English chronicler, and is the source of much of the knowledge of the reigns of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, and the careers of John Wycliff and Wat Tyler.

Walsingham was a Benedictine monk who sp ...

.

Death and legacy

From 1571 onwards, Walsingham complained of ill health and often retired to his country estate for periods of recuperation. He complained of "sundry carnosities", pains in his head, stomach and back, and difficulty in passing urine. Suggested diagnoses include cancer, kidney stones, urinary infection, and diabetes. He died on 6 April 1590, at his house in Seething Lane. Historian William Camden wrote that Walsingham died from "a carnosity growing ''intra testium tunicas'' esticular cancer. He was buried privately in a simple ceremony at 10 pm on the following day, beside his son-in-law, inOld St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul, ...

. The grave and monument were destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

in 1666. His name appears on a modern monument in the crypt listing the important graves lost.

In his will, dated 12 December 1589, Walsingham complained of "the greatness of my debts and the mean state shall leave my wife and heirs in",Hutchinson, p. 253 but the true state of his finances is unclear.Hutchinson, p. 257 He received grants of land from the Queen, grants for the export of cloth and leases of customs in the northern and western ports. His primary residences, apart from the court, were in Seething Lane by the Tower of London (now the site of a Victorian office building called Walsingham House), at Barn Elms in

In his will, dated 12 December 1589, Walsingham complained of "the greatness of my debts and the mean state shall leave my wife and heirs in",Hutchinson, p. 253 but the true state of his finances is unclear.Hutchinson, p. 257 He received grants of land from the Queen, grants for the export of cloth and leases of customs in the northern and western ports. His primary residences, apart from the court, were in Seething Lane by the Tower of London (now the site of a Victorian office building called Walsingham House), at Barn Elms in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

and at Odiham in Hampshire. Nothing remains of any of his houses.Adams et al. He spent much of his own money on espionage in the service of the Queen and the Protestant cause. In 1586, he funded a lectureship in theology at Oxford University for the Puritan John Rainolds. He had underwritten the debts of his son-in-law, Sir Philip Sidney, had pursued the Sidney estate for recompense unsuccessfully and had carried out major land transactions in his later years. After his death, his friends reflected that poor bookkeeping had left him further in the Crown's debt than was fair. In 1611, the Crown's debts to him were calculated at over £48,000, but his debts to the Crown were calculated at over £43,000 and a judge, Sir Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, ordered both sets of debts cancelled ''quid pro quo

Quid pro quo ('what for what' in Latin) is a Latin phrase used in English to mean an exchange of goods or services, in which one transfer is contingent upon the other; "a favor for a favor". Phrases with similar meanings include: "give and take", ...

''. Walsingham's surviving daughter Frances received a £300 annuity, and married the Earl of Essex. Ursula, Lady Walsingham, continued to live at Barn Elms with a staff of servants until her death in 1602.

Protestants lauded Walsingham as "a sound pillar of our commonwealth and chief patron of virtue, learning and chivalry". He was part of a Protestant intelligentsia that included Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

and John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divinatio ...

: men who promoted an expansionist and nationalist English Renaissance. Spenser included a dedicatory sonnet to Walsingham in the '' Faerie Queene'', likening him to Maecenas who introduced Virgil to the Emperor Augustus. After Walsingham's death, Sir John Davies composed an acrostic

An acrostic is a poem or other word composition in which the ''first'' letter (or syllable, or word) of each new line (or paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text) spells out a word, message or the alphabet. The term comes from the Fre ...

poem in his memory and Watson wrote an elegy, ''Meliboeus'', in Latin. On the other hand, Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Robert Persons thought Walsingham "cruel and inhumane" in his persecution of Catholics. Catholic sources portray a ruthless, devious man driven by religious intolerance and an excessive love for intrigue. Walsingham attracts controversy still. Although he was ruthless, his opponents on the Catholic side were no less so; the treatment of prisoners and suspects by Tudor authorities was typical of European governments of the time. Walsingham's personal, as opposed to his public, character is elusive; his public papers were seized by the government while many of his private papers, which might have revealed much, were lost. The fragments that do survive demonstrate his personal interest in gardening and falconry.

Portrayal in fiction

Fictional portrayals of Walsingham tend to follow Catholic interpretations, depicting him as sinister and Machiavellian. He features in conspiracy theories surrounding the death ofChristopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

, whom he predeceased. Charles Nicholl

Charles "Boomer" Bowen Nicholl (19 June 1870 – 9 July 1939) was a Welsh international rugby union forward who played club rugby for Cambridge University and Llanelli. Nicholl played for Wales on fifteen occasions during the 1891 and 1896 Ho ...

examined (and rejected) such theories in ''The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe'' (1992), which was used as a source by Anthony Burgess for his novel ''A Dead Man in Deptford

''A Dead Man in Deptford'' is a 1993 novel by Anthony Burgess, the last to be published during his lifetime. It depicts the life and character of Christopher Marlowe, a renowned playwright of the Elizabethan era.

Plot

Reckless but brilliant C ...

'' (1993).

The 1998 film '' Elizabeth'' gives considerable, although sometimes historically inaccurate, prominence to Walsingham (portrayed by Geoffrey Rush). It fictionalizes him as irreligious and sexually ambiguous, merges chronologically distant events, and inaccurately suggests that he murdered Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. She ...

. Rush reprised the role in the 2007 sequel, '' Elizabeth: The Golden Age''. Both Stephen Murray in the 1971 BBC series ''Elizabeth R

''Elizabeth R'' is a BBC television drama serial of six 85-minute plays starring Glenda Jackson as Queen Elizabeth I of England. It was first broadcast on BBC2 from February to March 1971, through the ABC in Australia and broadcast in America ...

'' and Patrick Malahide in the 2005 Channel Four miniseries '' Elizabeth I'' play him as a dour official.Latham, pp. 203, 240

Explanatory notes

Citations

References

* Adams, Simon; Bryson, Alan; Leimon, Mitchell (2004).Walsingham, Sir Francis (c. 1532–1590)

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online ed. May 2009, (subscription required) * Cooper, John (2011). ''The Queen's Agent: Francis Walsingham at the Court of Elizabeth I''. London: Faber & Faber. . * Fraser, Antonia (1994) 969 ''Mary Queen of Scots''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. . * Hasler, P. W. (1981).

Walsingham, Francis (c. 1532–90), of Scadbury and Foots Cray, Kent; Barn Elms, Surr. and Seething Lane, London

, ''History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603''. * Hutchinson, Robert (2007). ''Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the Secret War that Saved England''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. . * Latham, Bethany (2011).

Elizabeth I in Film and Television: A Study of the Major Portrayals

'. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. . * Parker, Geoffrey (2000). ''The Grand Strategy of Philip II''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. . * Rozett, Martha Tuck (2003).

Constructing a World: Shakespeare's England and the New Historical Fiction

'. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. . * Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2012). ''Western Civilization: Since 1500''. Eighth edition. Boston: Wadsworth. . * Wilson, Derek (2007). ''Sir Francis Walsingham: A Courtier in an Age of Terror''. New York: Carroll & Graf. .

Further reading

*Bossy, John

John Antony Bossy FBA (30 April 1933 – 23 October 2015) was a British historian who was a professor of history at the University of York.

Career

Bossy was educated at Queens' College, Cambridge, where he was inspired by Walter Ullmann. He ...

(1991). ''Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair''. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. .

* Budiansky, Stephen (2005). Her Majesty's Spymaster: Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the Birth of Modern Espionage

'. New York: Viking. . * Haynes, Alan (2004). ''Walsingham: Elizabethan Spymaster & Statesman''. Stroud, Glos.: Sutton. . * Hutchinson, John (1892). Sir Francis Walsingham". ''Men of Kent and Kentishmen''. Canterbury: Cross & Jackman. pp. 140–141. * * * * Read, Conyers (1925). ''Mr Secretary Walsingham and the Policy of Queen Elizabeth''. Oxford: Clarendon Press (an exhaustive three-volume biography that is still valuable despite its age). Via the Internet Archive

Volume 1

Volume 2

, an

Volume 3

.

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Walsingham, Francis 1530s births 1590 deaths 16th-century English diplomats 16th-century spies Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Ambassadors of England to France Ambassadors of England to Scotland Burials at St Paul's Cathedral Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Chancellors of the Order of the Garter English knights English spies Members of Gray's Inn People from Chislehurst Secretaries of State of the Kingdom of England SpymastersFrancis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural M ...

Year of birth uncertain