Sir Alexander Cunningham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cunningham was born in London in 1814 to the

Cunningham was born in London in 1814 to the

In 1841 Cunningham was made executive engineer to the

In 1841 Cunningham was made executive engineer to the

Following his retirement from the Royal Engineers in 1861,

Following his retirement from the Royal Engineers in 1861,

LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries

' (1854). *

Bhilsa Topes

' (1854), a history of

The Ancient Geography of India

' (1871) *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 1

' (1871

Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65, Volume 1

(1871) *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 2

' *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 3

' (1873) *

Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Volume 1.

' (1877) *

The Stupa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century B.C.

' (1879) *

The Book of Indian Eras

' (1883) *

Coins of Ancient India

' (1891) *

Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya

' (1892) * ''Coins of Medieval India'' (1894) * ''Report of Tour in Eastern Rajputana'' Additional works: * ''The World of India’s First Archaeologist: Letters from Alexander Cunningham to J.D.M. Beglar''; Oxford University Press: Upinder Singh. *''Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginnings of Indian Archeology'' by Imam, Abu. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies (United Kingdom). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1963. 11010387. https://www.proquest.com/openview/7f3e68a8133dd31b58d184849667486f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

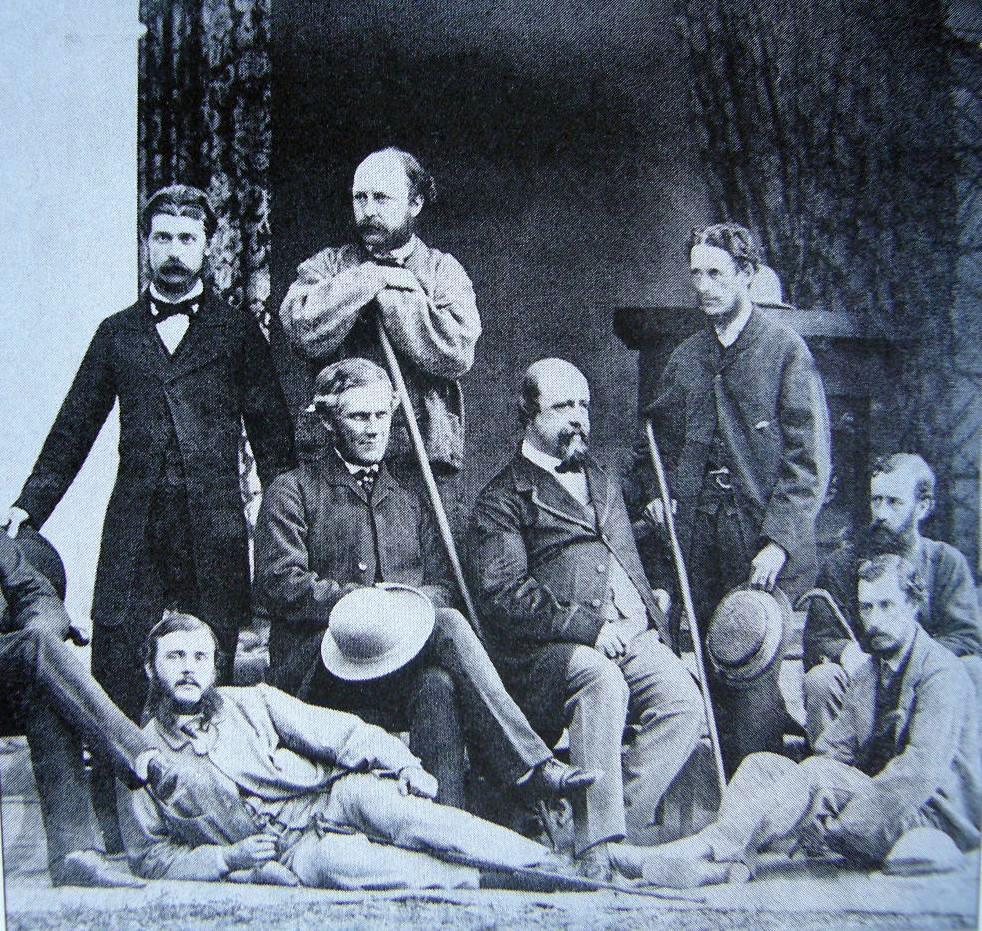

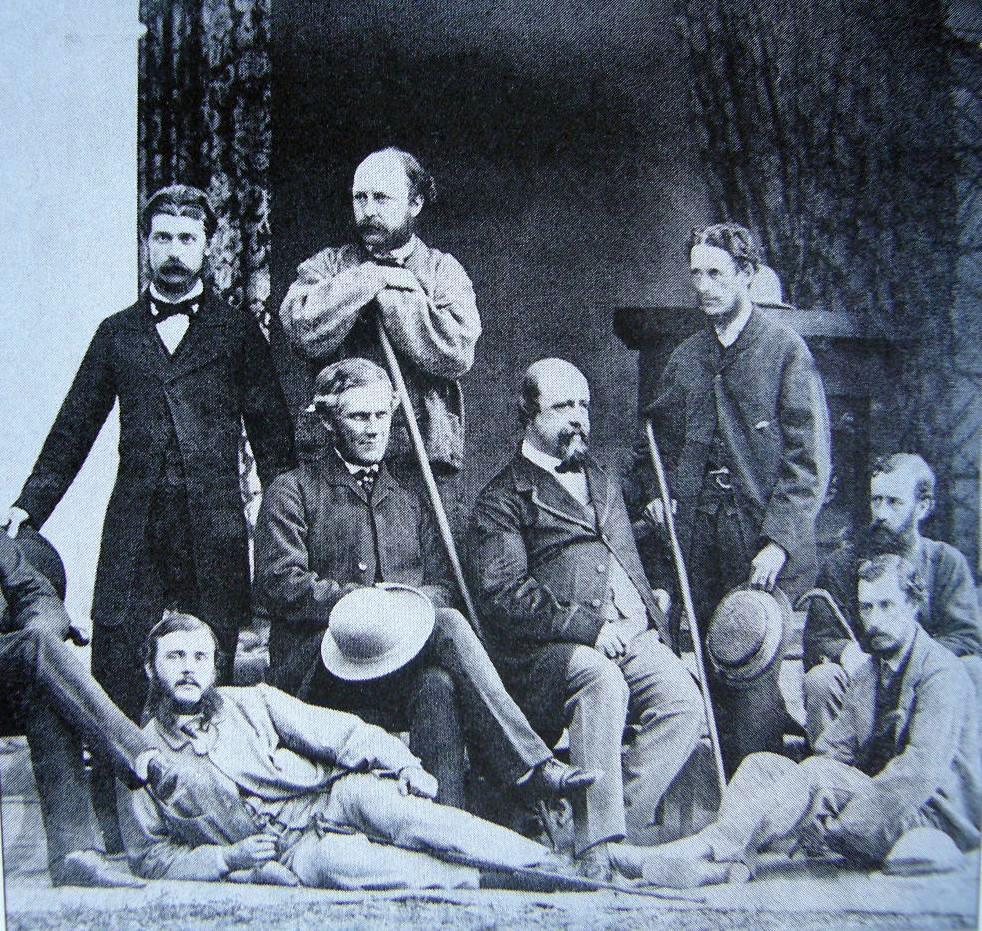

Sir Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was a British Army engineer with the Bengal Engineer Group

The Bengal Engineer Group (BEG) (informally the Bengal Sappers or Bengal Engineers) is a military engineering regiment in the Corps of Engineers of the Indian Army. The unit was originally part of the Bengal Army of the East India Company's Ben ...

who later took an interest in the history and archaeology of India. In 1861, he was appointed to the newly created position of archaeological surveyor to the government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

; and he founded and organised what later became the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexande ...

.

He wrote numerous books and monographs and made extensive collections of artefacts. Some of his collections were lost, but most of the gold and silver coins and a fine group of Buddhist sculpture

Buddhist art is visual art produced in the context of Buddhism. It includes depictions of Gautama Buddha and other Buddhas and bodhisattvas, notable Buddhist figures both historical and mythical, narrative scenes from their lives, mandalas, and ...

s and jewellery were bought by the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

in 1894. He was also the father of mathematician Allan Cunningham.

Early life and career

Cunningham was born in London in 1814 to the

Cunningham was born in London in 1814 to the Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

poet Allan Cunningham (1784–1842) and his wife Jean née Walker (1791–1864). Along with his older brother, Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, he received his early education at Christ's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex. The school was founded in 1552 and received its first royal charter in 1553 ...

, London. Through the influence of Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

, both Joseph and Alexander obtained cadetships at the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

's Addiscombe Seminary (1829–31), followed by technical training at the Royal Engineers Estate at Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

. Alexander joined the Bengal Engineers

The Bengal Engineer Group (BEG) (informally the Bengal Sappers or Bengal Engineers) is a military engineering regiment in the Corps of Engineers of the Indian Army. The unit was originally part of the Bengal Army of the East India Company's Ben ...

at the age of 19 as a Second Lieutenant and spent the next 28 years in the service of British Government of India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. Soon after arriving in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

on 9 June 1833, he met James Prinsep

James Prinsep FRS (20 August 1799 – 22 April 1840) was an English scholar, orientalist and antiquary. He was the founding editor of the ''Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal'' and is best remembered for deciphering the Kharosthi and B ...

. He was in daily communication with Prinsep during 1837 and 1838 and became his intimate friend, confidant and pupil. Prinsep passed on to him his lifelong interest in Indian archaeology and antiquity.

From 1836 to 1840 he was ADC

ADC may refer to:

Science and medicine

* ADC (gene), a human gene

* AIDS dementia complex, neurological disorder associated with HIV and AIDS

* Allyl diglycol carbonate or CR-39, a polymer

* Antibody-drug conjugate, a type of anticancer treatment ...

to Lord Auckland

Baron Auckland is a title in both the Peerage of Ireland and the Peerage of Great Britain. The first creation came in 1789 when the prominent politician and financial expert William Eden was made Baron Auckland in the Peerage of Ireland. In ...

, the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of India. During this period he visited Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, which was then not well explored. He finds mention by initials in ''Up the Country'' by Emily Eden

Emily Eden (3 March 1797 – 5 August 1869) was an English poet and novelist who gave witty accounts of English life in the early 19th century. She wrote a celebrated account of her travels in India, and two novels that sold well. She was also a ...

.

Military life

In 1841 Cunningham was made executive engineer to the

In 1841 Cunningham was made executive engineer to the king of Oudh

The Nawab of Awadh or the Nawab of Oudh was the title of the rulers who governed the state of Awadh (anglicised as Oudh) in north India during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Nawabs of Awadh belonged to a dynasty of Persian origin from Nishapu ...

. In 1842 he was called to serve the army in thwarting an uprising in Bundelkhand

Bundelkhand (, ) is a geographical and cultural region and a proposed state and also a mountain range in central & North India. The hilly region is now divided between the states of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, with the larger portion lyin ...

by the ruler of Jaipur. He was then posted at Nowgong in central India before he saw action at the Battle of Punniar in December 1843. He became engineer at Gwalior

Gwalior() is a major city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh; it lies in northern part of Madhya Pradesh and is one of the Counter-magnet cities. Located south of Delhi, the capital city of India, from Agra and from Bhopal, the s ...

and was responsible for constructing an arched stone bridge over the Morar River in 1844–45. In 1845–46 he was called to serve in Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

and helped construct two bridges of boats across the Beas river

The Beas River (Sanskrit: ; Hyphasis in Ancient Greek) is a river in north India. The river rises in the Himalayas in central Himachal Pradesh, India, and flows for some to the Sutlej River in the Indian state of Punjab. Its total length is ...

prior to the Battle of Sobraon

The Battle of Sobraon was fought on 10 February 1846, between the forces of the East India Company and the Sikh Khalsa Army, the army of the Sikh Empire of the Punjab. The Sikhs were completely defeated, making this the decisive battle of the F ...

.

In 1846, he was made commissioner along with P. A. Vans Agnew

Patrick Alexander Vans Agnew (1822–1848) was a British civil servant of the East India Company, whose murder during the Siege of Multan by the retainers of Dewan Mulraj led to the Second Sikh War and to the British annexation of the Punjab region ...

to demarcate boundaries. Letters were written to the Chinese and Tibetan officials by Lord Hardinge, but no officials joined. A second commission was set up in 1847 which was led by Cunningham to establish the Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

-Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

boundary, which also included Henry Strachey and Thomas Thomson Thomas Thomson may refer to:

* Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Canadian painter

* Thomas Thomson (apothecary) (died 1572), Scottish apothecary

* Thomas Thomson (advocate) (1768–1852), Scottish lawyer

* Thomas Thomson (botanist) (1817–1878), Scottis ...

. Henry and his brother Richard Strachey

Sir Richard Strachey (24 July 1817 – 12 February 1908) was a British soldier and Indian administrator, the third son of Edward Strachey and grandson of Sir Henry Strachey, 1st Baronet.

Early life

He was born on 24 July 1817, at Sutton ...

had trespassed into Lake Mansarovar and Rakas Tal in 1846 and his brother Richard revisited in 1848 with botanist J. E. Winterbottom. The commission was set up to delimit the northern boundaries of the Empire after the First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh War was fought between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company in 1845 and 1846 in and around the Ferozepur district of Punjab. It resulted in defeat and partial subjugation of the Sikh empire and cession of ...

concluded with the Treaty of Amritsar

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, which ceded Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

as war indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

expenses to the British. His early work ''Essay on the Aryan Order of Architecture'' (1848) arose from his visits to the temples in Kashmir and his travels in Ladakh during his tenure with the commission. He was also present at the battles of Chillianwala

Chillianwala is a village and union council of Mandi Bahauddin District in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It is located at 32°39'0N 73°36'0E at an altitude of 218 metres (718 feet) and lies to the north-east of the district capital Mandi ...

and Gujrat in 1848–49. In 1851, he explored the Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

monuments of Central India

Central India is a loosely defined geographical region of India. There is no clear official definition and various ones may be used. One common definition consists of the states of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, which are included in alm ...

along with Lieutenant Maisey and wrote an account of these.

In 1856 he was appointed chief engineer of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, which had just been annexed by Britain, for two years; and from 1858 served for three years in the same post in the North-Western Provinces

The North-Western Provinces was an administrative region in British India. The North-Western Provinces were established in 1836, through merging the administrative divisions of the Ceded and Conquered Provinces. In 1858, the nawab-ruled kingdom ...

. In both regions, he established public works departments. He was therefore absent from India during the Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

. He was appointed Colonel of the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

in 1860. He retired on 30 June 1861, having attained the rank of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

Archaeology

Cunningham had taken a keen interest in antiquities from early on in his career. Following the activities ofJean-Baptiste Ventura

Jean-Baptiste (Giovanni Battista) Ventura, born Rubino (25 May 1794 – 3 April 1858), was an Italian soldier, mercenary in India, general in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sarkar-i-Khalsa, and early archaeologist of the Punjab region of the Sikh Empi ...

(general of Ranjit Singh

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839), popularly known as Sher-e-Punjab or "Lion of Punjab", was the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, which ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He s ...

)—who, inspired by the French explorers in Egypt, had excavated the bases of pillars to discover large stashes of Bactrian and Roman coins—excavations became a regular activity among British antiquarians.

In 1834 he submitted to the ''Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal

The Asiatic Society is a government of India organisation founded during the Company rule in India to enhance and further the cause of "Oriental research", in this case, research into India and the surrounding regions. It was founded by the p ...

,'' an appendix to James Prinsep

James Prinsep FRS (20 August 1799 – 22 April 1840) was an English scholar, orientalist and antiquary. He was the founding editor of the ''Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal'' and is best remembered for deciphering the Kharosthi and B ...

's article, on the relics in the Mankiala stupa

The Manikyala Stupa ( ur, ) is a Buddhist stupa near the village of Tope Mankiala, in Pakistan's Punjab province. The stupa was built to commemorate the spot, where according to the Jataka tales, an incarnation of the Buddha called Prince Satt ...

. He had conducted excavations at Sarnath

Sarnath (Hindustani pronunciation: aːɾnaːtʰ also referred to as Sarangnath, Isipatana, Rishipattana, Migadaya, or Mrigadava) is a place located northeast of Varanasi, near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pr ...

in 1837 along with Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

F. C. Maisey and made careful drawings of the sculptures. In 1842 he excavated at Sankassa

Sankissa (also Sankasia, Sankassa and Sankasya) was an ancient city in India. The city came into prominence at the time of Gautama Buddha. According to a Buddhist source, it was thirty leagues from Savatthi.''Dhammapadatthakathā'', iii, 224 Af ...

and at Sanchi

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the States and territories of India, State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen, Raisen town, dist ...

in 1851. In 1854, he published ''The Bhilsa Topes'', a piece of work which attempted to establish the history of Buddhism

The history of Buddhism spans from the 5th century BCE to the present. Buddhism arose in Ancient India, in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha, and is based on the teachings of the ascetic Siddhārtha Gautama. The religion evolved as it sp ...

based on architectural evidence.

By 1851, he also began to communicate with William Henry Sykes

Colonel William Henry Sykes, FRS (25 January 1790 – 16 June 1872) was an English naturalist who served with the British military in India and was specifically known for his work with the Indian Army as a politician, Indologist and ornitholog ...

and the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

on the value of an archaeological survey. He provided a rationale for providing the necessary funding, arguing that the venture

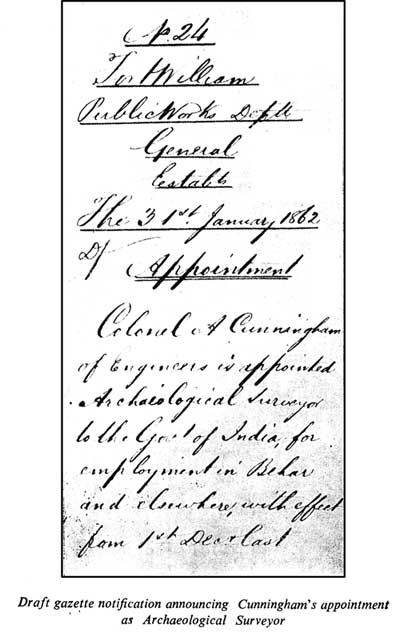

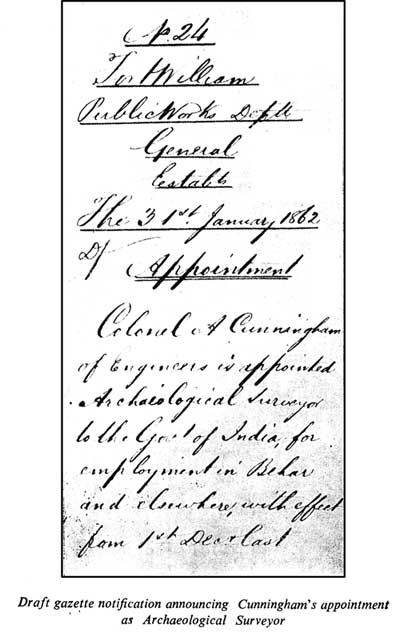

Following his retirement from the Royal Engineers in 1861,

Following his retirement from the Royal Engineers in 1861, Lord Canning

Charles Canning, 1st Earl Canning, (14 December 1812 – 17 June 1862), also known as The Viscount Canning and Clemency Canning, was a British statesman and Governor-General of India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the first Vice ...

, then Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, appointed Cunningham as an archaeological surveyor to the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

. He held this position from 1861 to 1865, but it was then terminated through lack of funds.

Most antiquarians of the 19th century who took interest in identifying the major cities, mentioned in ancient Indian texts, did so by putting together clues found in classical Graeco-Roman chronicles and the travelogues of travellers to India such as Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

and Faxian

Faxian (法顯 ; 337 CE – c. 422 CE), also referred to as Fa-Hien, Fa-hsien and Sehi, was a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India to acquire Buddhist texts. Starting his arduous journey about age 60, h ...

. Cunningham was able to identify some of the places mentioned by Xuanzang, and counted among his major achievements the identification of Aornos

Aornos ( grc, Ἄορνος) was site of Alexander the Great's last siege, which took place on April 326 BC, at a mountain site located in modern Pakistan. Aornos offered the last threat to Alexander's supply line, which stretched, dangerousl ...

, Ahichchhatra

Ahichchhatra ( sa, अहिच्छत्र, translit=Ahicchatra) or Ahikshetra ( sa, अहिक्षेत्र, translit=Ahikṣetra), near the modern Ramnagar village in Aonla tehsil, Bareilly district in Uttar Pradesh, India, was the ...

, Bairat

Viratnagar previously known as Bairat (IAST: ) or Bairath (IAST: ) is a town in northern Jaipur district of Rajasthan, India.

History

Ancient era

According to Huen Tsang, visitor to China, Tonk was under Bairath State or Viratnagar pre ...

, Kosambi

Kosambi (Pali) or Kaushambi (Sanskrit) was an important city in ancient India. It was the capital of the Vatsa kingdom, one of the sixteen mahajanapadas. It was located on the Yamuna River about southwest of its confluence with the Ganges at ...

, Nalanda

Nalanda (, ) was a renowned ''mahavihara'' (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), India.Padmavati

Padmāvatī may refer to:

Deities

* Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of fortune

* Alamelu, or Padmāvatī, a Hindu goddess and consort of Sri Venkateshwara of Tirupati

* Manasa, a Hindu serpent goddess

* Padmavati (Jainism), a Jain attendant goddess ( ...

, Sangala

Sagala, Sakala ( sa, साकला), or Sangala ( grc, Σάγγαλα) was a city in ancient India, which was the predecessor of the modern city of Sialkot that is located in what is now Pakistan's northern Punjab province. The city was the ...

, Sankisa, Shravasti

Shravasti ( sa, श्रावस्ती, translit=Śrāvastī; pi, 𑀲𑀸𑀯𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀻, translit=Sāvatthī) is a city and district headquarter of Shravasti district in Indian State of Uttar Pradesh. It was the capital of the an ...

, Srughna

Srughna, also spelt Shrughna in Sanskrit, or Sughna, Sughana or Sugh in the spoken form, was an ancient city or kingdom of India frequently referred to in early and medieval texts. It was visited by Chinese traveller, Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) in ...

, Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

, and Vaishali. Unlike his contemporaries, Cunningham would also routinely confirm his identifications through field surveys. The identification of Taxila, in particular, was made difficult partly due to errors in the distances recorded by Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

in his Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

which pointed to a location somewhere on the Haro River

Haro ( ur, ) is the name of a river that flows through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and parts of Punjab. Its main valley is in Abbottabad District in the Hazara Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, northern Pakistan. The famous Khanpur Dam has been bu ...

, a two-day march from the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

. Cunningham noticed that this position did not tally with the itineraries of Chinese pilgrims and in particular, the descriptions provided by Xuanzang. Unlike Pliny, these sources noted that the journey to Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

from the Indus took three days and not two and therefore, suggested a different location for the city. Cunningham's subsequent explorations in 1863–64 of a site at Shah-dheri convinced him that his hypothesis was correct.

After his department was abolished in 1865, Cunningham returned to England and wrote the first part of his ''Ancient Geography of India'' (1871), covering the Buddhist period; but failed to complete the second part, covering the Muslim period. During this period in London he worked as director of the Delhi and London Bank

The Delhi and London Bank was a bank that operated in British India. It was originally incorporated as the Delhi Banking Corporation in India in 1844 and under this better known name in London in 1865. The bank separated in 1916 with many of the In ...

. In 1870, Lord Mayo

Richard Southwell Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo, (; ; 21 February 1822 – 8 February 1872) styled Lord Naas (; ) from 1842 to 1867 and Lord Mayo in India, was a British politician, statesman and prominent member of the Conservative Party (UK), ...

re-established the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexande ...

, with Cunningham as its director-general from 1 January 1871. Cunningham returned to India and made field explorations each winter, conducting excavations and surveys from Taxila to Gaur. He produced twenty-four reports, thirteen as author and the rest under his supervision by others such as J. D. Beglar. Other major works included the first volume of ''Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexander ...

'' (1877) which included copies of the edicts of Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, ''The Stupa of Bharhut

Bharhut is a village located in the Satna district of Madhya Pradesh, central India. It is known for its famous relics from a Buddhist stupa. What makes Bharhut panels unique is that each panel is explicitly labelled in Brahmi characters mentioni ...

'' (1879) and the ''Book of Indian Eras'' (1883) which allowed the dating of Indian antiquities. He retired from the Archaeological Survey on 30 September 1885 and returned to London to continue his research and writing.

Numismatic interests

Cunningham assembled a largenumismatic

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also includ ...

collection, but much of this was lost when the steamship he was travelling in, the ''Indus'', was wrecked off the coast of Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

in November 1884. The British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, however, obtained most of the gold and silver coins. He had suggested to the Museum that they should use the arch from the Sanchi Stupa

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen town, district headquarter and north-east of Bhop ...

to mark the entrance of a new section on Indian history. He also published numerous papers in the ''Journal of the Asiatic Society

The Asiatic Society is a government of India organisation founded during the Company rule in India to enhance and further the cause of "Oriental research", in this case, research into India and the surrounding regions. It was founded by the ph ...

'' and the ''Numismatic Chronicle

The Royal Numismatic Society (RNS) is a learned society and charity based in London, United Kingdom which promotes research into all branches of numismatics. Its patron was Queen Elizabeth II.

Membership

Foremost collectors and researchers, bo ...

''.

Family and personal life

Two of Cunningham's brothers,Francis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural M ...

and Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, became well known for their work in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

; while another, Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

, became famous for his ''Handbook of London'' (1849).

Cunningham married Alicia Maria Whish, daughter of Martin Whish, B.C.S., on 30 March 1840. The couple had two sons, Lieutenant-Colonel Allan J. C. Cunningham

Allan Joseph Champneys Cunningham (1842–1928) was a British-Indian mathematician.A. E. Western, ''J. London Math. Soc.'' 317–318 (1928)

Biography

Born in Delhi, Cunningham was the son of Sir Alexander Cunningham, archaeologist and the founde ...

(1842–1928) of the Bengal and Royal Engineers, and Sir Alexander F. D. Cunningham (1852–1935) of the Indian Civil Service.

Cunningham died on 28 November 1893 at his home in South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederic ...

, London. His wife had predeceased him. He was survived by his two sons.

Awards and memorials

Cunningham was awarded the CSI on 20 May 1870 and CIE in 1878. In 1887, he was made aKnight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire

The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria on 1 January 1878. The Order includes members of three classes:

#Knight Grand Commander (GCIE)

#Knight Commander ( KCIE)

#Companion ( CIE)

No appoi ...

.

Publications

Books written by Cunningham include: *LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries

' (1854). *

Bhilsa Topes

' (1854), a history of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

* The Ancient Geography of India

' (1871) *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 1

' (1871

Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65, Volume 1

(1871) *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 2

' *

Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 3

' (1873) *

Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Volume 1.

' (1877) *

The Stupa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century B.C.

' (1879) *

The Book of Indian Eras

' (1883) *

Coins of Ancient India

' (1891) *

Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya

' (1892) * ''Coins of Medieval India'' (1894) * ''Report of Tour in Eastern Rajputana'' Additional works: * ''The World of India’s First Archaeologist: Letters from Alexander Cunningham to J.D.M. Beglar''; Oxford University Press: Upinder Singh. *''Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginnings of Indian Archeology'' by Imam, Abu. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies (United Kingdom). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1963. 11010387. https://www.proquest.com/openview/7f3e68a8133dd31b58d184849667486f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cunningham, Alexander 1814 births 1893 deaths Companions of the Order of the Star of India English archaeologists Knights Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire Explorers of Central Asia Bengal Engineers officers British people in colonial India British Army major generals British military personnel of the Gwalior Campaign Alumni of Addiscombe Military Seminary People educated at Christ's Hospital 19th-century archaeologists Directors General of the Archaeological Survey of India