The Sino-Indian War took place between

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and

India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the

Sino-Indian border dispute

The Sino-Indian border dispute is an ongoing territorial dispute over the sovereignty of two relatively large, and several smaller, separated pieces of territory between China and India. The first of the territories, Aksai Chin, is administe ...

. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the

1959 Tibetan uprising

The 1959 Tibetan uprising (also known by other names) began on 10 March 1959, when a revolt erupted in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, which had been under the effective control of the People's Republic of China since the Seventeen Point Agreemen ...

, when India granted asylum to the

Dalai Lama. Chinese military action grew increasingly aggressive after India rejected proposed Chinese diplomatic settlements throughout 1960–1962, with China re-commencing previously-banned "forward patrols" in

Ladakh after 30 April 1962. Amidst the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, China abandoned all attempts towards a peaceful resolution on 20 October 1962, invading disputed territory along the border in Ladakh and across the

McMahon Line in the northeastern frontier.

Chinese troops pushed back Indian forces in both theatres, capturing all of their claimed territory in the western theatre and the

Tawang Tract in the eastern theatre. The conflict ended when China unilaterally declared a ceasefire on 20 November 1962, and simultaneously announced its withdrawal to its claimed "

Line of Actual Control" (i.e., the effective China–India border).

Much of the fighting comprised

mountain warfare, entailing large-scale combat at altitudes of over .

The Sino-Indian War was also notable for the lack of deployment of naval and aerial assets by either China or India.

As the

Sino-Soviet split deepened, the

Soviet Union made a major effort to support India, especially with the sale of advanced

MiG fighter-aircraft. Simultaneously, the

United States and the

United Kingdom refused to sell advanced weaponry to India, further compelling it to turn to the Soviets for military aid.

Location

China and India shared a long border, sectioned into three stretches by

Nepal,

Sikkim (then an Indian

protectorate), and

Bhutan, which follows the

Himalayas between

Burma and what was then

West Pakistan. A number of disputed regions lie along this border. At its western end is the

Aksai Chin region, an area the size of

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, that sits between the Chinese autonomous region of

Xinjiang and

Tibet (which China declared as an autonomous region in 1965). The eastern border, between Burma and Bhutan, comprises the present Indian state of

Arunachal Pradesh (formerly the

North-East Frontier Agency). Both of these regions were overrun by China in the 1962 conflict.

Most combat took place at high elevations. The Aksai Chin region is a desert of salt flats around above sea level, and Arunachal Pradesh is mountainous with a number of peaks exceeding . The

Chinese Army had possession of one of the highest ridges in the regions. The high altitude and freezing conditions also caused logistical and welfare difficulties; in past similar conflicts (such as the

Italian Campaign of

World War I) harsh conditions have caused more casualties than have enemy actions. The Sino-Indian War was no different, with many troops on both sides succumbing to the freezing cold temperatures.

Background

The main cause of the war was a dispute over the

sovereignty of the widely separated Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh border regions. Aksai Chin, claimed by India to belong to

Ladakh and by China to be part of Xinjiang, contains an important road link that connects the Chinese regions of Tibet and Xinjiang. China's construction of this road was one of the triggers of the conflict.

Aksai Chin

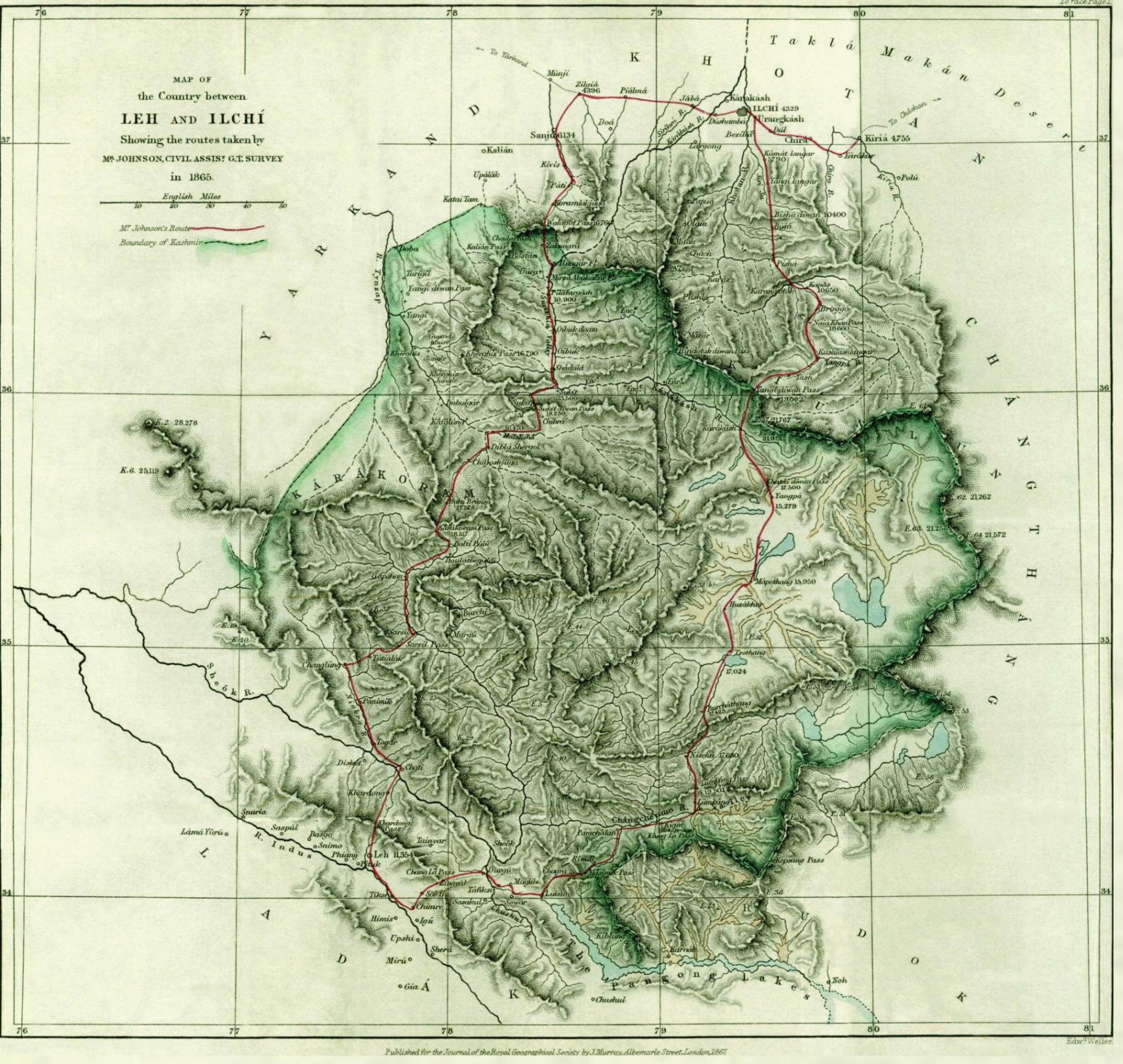

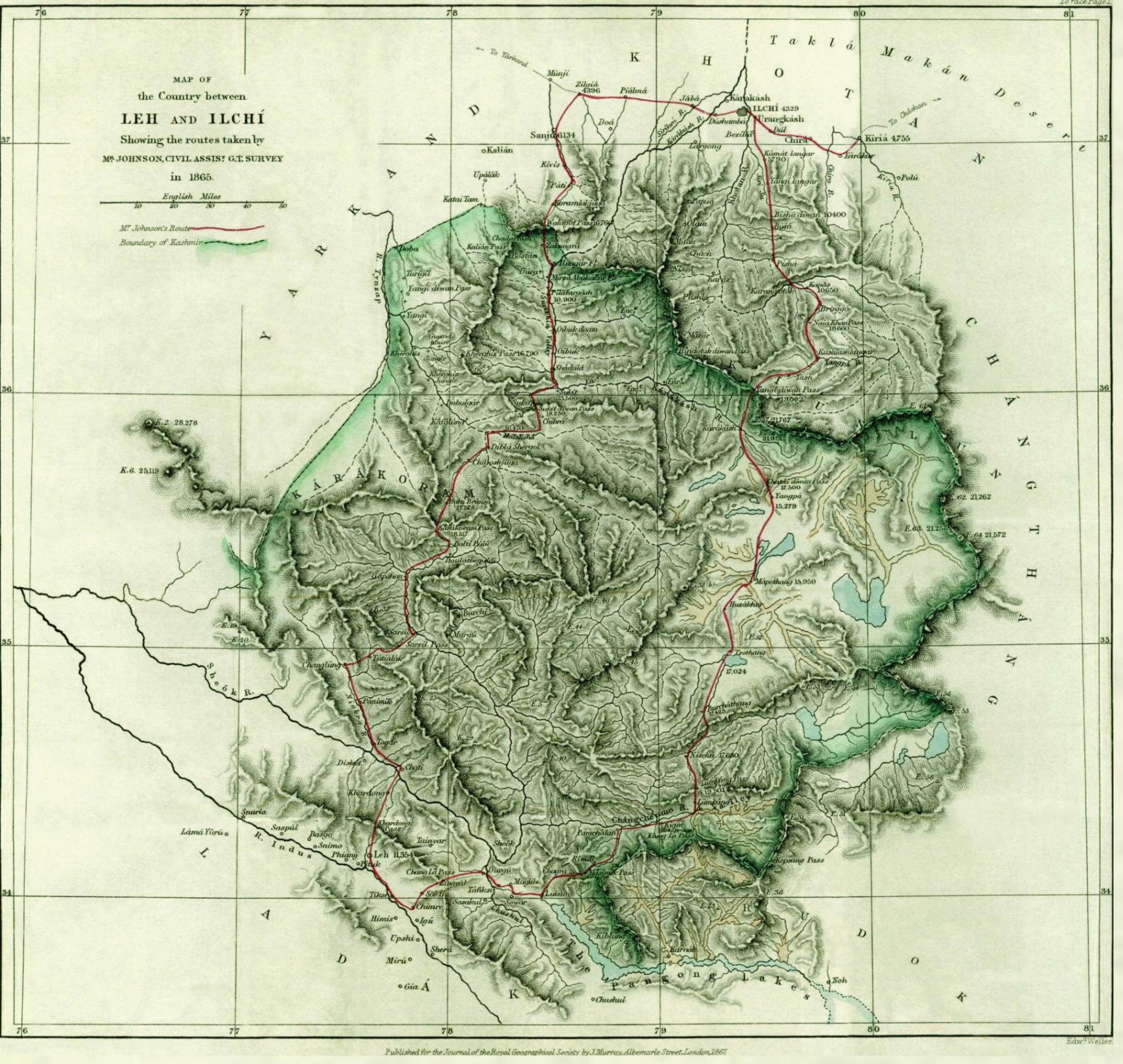

The western portion of the Sino-Indian boundary originated in 1834, with the conquest of Ladakh by the armies of Raja

Gulab Singh (Dogra) under the suzerainty of the

Sikh Empire. Following an

unsuccessful campaign into Tibet, Gulab Singh and the Tibetans signed a

treaty in 1842 agreeing to stick to the "old, established frontiers", which were left unspecified.

[The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan. 1960), pp. 96–125, .] The

British defeat of the Sikhs in 1846 resulted in the transfer of the

Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

region including Ladakh to the British, who then installed Gulab Singh as the Maharaja under their suzerainty. British commissioners contacted Chinese officials to negotiate the border, who did not show any interest. The British boundary commissioners fixed the southern end of the boundary at

Pangong Lake, but regarded the area north of it till the

Karakoram Pass as ''terra incognita''.

The Maharaja of Kashmir and his officials were keenly aware of the trade routes from Ladakh. Starting from

Leh, there were two main routes into Central Asia: one passed through the Karakoram Pass to

Shahidulla

Shahidulla, also spelt Xaidulla from Mandarin Chinese, (altitude ca. 3,646 m or 11,962 ft), was a nomad camping ground and historical caravan halting place in the Karakash River valley, close to Khotan, in the southwestern part of Xinjiang Au ...

at the foot of the

Kunlun Mountains

The Kunlun Mountains ( zh, s=昆仑山, t=崑崙山, p=Kūnlún Shān, ; ug, كۇئېنلۇن تاغ تىزمىسى / قۇرۇم تاغ تىزمىسى ) constitute one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than . In the bro ...

and went on to

Yarkand

Yarkant County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also Shache County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also transliterated from Uyghur as Yakan County, is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous ...

through the Kilian and Sanju passes; the other went east via the

Chang Chenmo Valley

Chang Chenmo River or Changchenmo River is a tributary of the Shyok River, part of the Indus River system. It is at the southern edge of the disputed Aksai Chin region and north of the Pangong Lake basin.

The source of Chang Chenmo is near th ...

, passed the

Lingzi Tang Plains

(), also called (), refers to a traditional Chinese ornament which uses long pheasant tail feather appendages to decorate some headdress in , Chinese opera costumes. In Chinese opera, the not only decorative purpose but are also used express ...

in the Aksai Chin region, and followed the course of the

Karakash River to join the first route at Shahidulla. The Maharaja regarded Shahidulla as his northern outpost, in effect treating the Kunlun mountains as the boundary of his domains. His British suzerains were sceptical of such an extended boundary because Shahidulla was away from the Karakoram Pass and the intervening area was uninhabited. Nevertheless, the Maharaja was allowed to treat Shahidulla as his outpost for more than 20 years.

Chinese Turkestan regarded the "northern branch" of the Kunlun range with the Kilian and Sanju passes as its southern boundary. Thus the Maharaja's claim was uncontested. After the 1862

Dungan Revolt, which saw the expulsion of the Chinese from Turkestan, the Maharaja of Kashmir constructed a small fort at Shahidulla in 1864. The fort was most likely supplied from

Khotan, whose ruler was now independent and on friendly terms with Kashmir. When the Khotanese ruler was deposed by the Kashgaria strongman

Yakub Beg, the Maharaja was forced to abandon his post in 1867. It was then occupied by Yakub Beg's forces until the end of the Dungan Revolt.

In the intervening period,

W. H. Johnson of

Survey of India

The Survey of India is India's central engineering agency in charge of Cartography, mapping and surveying. was commissioned to survey the Aksai Chin region. While in the course of his work, he was "invited" by the Khotanese ruler to visit his capital. After returning, Johnson noted that Khotan's border was at Brinjga, in the Kunlun mountains, and the entire the Karakash Valley was within the territory of Kashmir. The boundary of Kashmir that he drew, stretching from Sanju Pass to the

eastern edge of Chang Chenmo Valley along the Kunlun mountains, is referred to as the "

Johnson Line" (or "Ardagh-Johnson Line").

After the Chinese reconquered Turkestan in 1878, renaming it Xinjiang, they again reverted to their traditional boundary. By now, the Russian Empire was entrenched in Central Asia, and the British were anxious to avoid a common border with the Russians. After creating the

Wakhan corridor as the buffer in the northwest of Kashmir, they wanted the Chinese to fill out the "no man's land" between the Karakoram and Kunlun ranges. Under British (and possibly Russian) encouragement, the Chinese occupied the area up to the

Yarkand River valley (called

Raskam

The Yarkand River (or Yarkent River, Yeh-erh-ch'iang Ho) is a river in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of western China. It originates in the Siachen Muztagh in a part of the Karakoram range and flows into the Tarim River or Neinejoung Ri ...

), including Shahidulla, by 1890. They also erected a boundary pillar at the Karakoram pass by about 1892. These efforts appear half-hearted. A map provided by Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at

St. Petersburgh

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, in 1893 showed the boundary of Xinjiang up to Raskam. In the east, it was similar to the Johnson line, placing Aksai Chin in Kashmir territory.

By 1892, the British settled on the policy that their preferred boundary for Kashmir was the "Indus watershed", i.e., the water-parting from which waters flow into the Indus river system on one side and into the Tarim basin on the other. In the north, this water-parting was along the Karakoram range. In the east, it was more complicated because the

Chip Chap River,

Galwan River and the

Chang Chenmo River

Chang Chenmo River or Changchenmo River is a tributary of the Shyok River, part of the Indus River system. It is at the southern edge of the disputed Aksai Chin region and north of the Pangong Lake basin.

The source of Chang Chenmo is near th ...

flow into the Indus whereas the Karakash River flows into the Tarim basin. A boundary alignment along this water-parting was defined by the Viceroy

Lord Elgin and communicated to London. The British government in due course proposed it to China via its envoy Sir

Claude MacDonald

Colonel Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald, (12 June 1852 – 10 September 1915) was a British soldier and diplomat, best known for his service in China and Japan.

Early life

MacDonald was born the son of Mary Ellen MacDonald (''nee'' Dougan) and ...

in 1899. This boundary, which came to be called the

Macartney–MacDonald Line, ceded to China the Aksai Chin plains in the northeast, and the

Trans-Karakoram Tract in the north. In return, the British wanted China to cede its 'shadowy suzerainty' on

Hunza.

In 1911 the

Xinhai Revolution resulted in power shifts in China, and by the end of World War I, the British officially used the Johnson Line. They took no steps to establish outposts or assert control on the ground.

According to

Neville Maxwell

Neville Maxwell (1926 – 23 September 2019) was a British journalist and scholar who authored the 1970 book ''India's China War'', which is considered a revisionist analysis of the 1962 Sino-Indian War, putting the blame for it on India. Maxwe ...

, the British had used as many as 11 different boundary lines in the region, as their claims shifted with the political situation.

From 1917 to 1933, the "Postal Atlas of China", published by the Government of China in Peking had shown the boundary in Aksai Chin as per the Johnson line, which runs along the

Kunlun mountains

The Kunlun Mountains ( zh, s=昆仑山, t=崑崙山, p=Kūnlún Shān, ; ug, كۇئېنلۇن تاغ تىزمىسى / قۇرۇم تاغ تىزمىسى ) constitute one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than . In the bro ...

.

The "Peking University Atlas", published in 1925, also put the Aksai Chin in India. Upon

independence in 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin.

On 1 July 1954, India's first Prime Minister

Jawaharlal Nehru definitively stated the Indian position,

claiming that Aksai Chin had been part of the Indian Ladakh region for centuries, and that the border (as defined by the Johnson Line) was non-negotiable.

According to

George N. Patterson

George Neilson Patterson (born 19 August 1920 in Falkirk, died at Auchlochan, Lesmahagow, 28 December 2012) also known as Khampa Gyau (bearded Khampa in Tibetan) and Patterson of Tibet, was a Scottish engineer and missionary who served as medic ...

, when the Indian government finally produced a report detailing the alleged proof of India's claims to the disputed area, "the quality of the Indian evidence was very poor, including some very dubious sources indeed".

[George W. Patterson, Peking Versus Delhi, Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1963]

In 1956–57, China constructed a road through Aksai Chin, connecting Xinjiang and Tibet, which ran south of the Johnson Line in many places.

Aksai Chin was easily accessible to the Chinese, but access from India, which meant negotiating the Karakoram mountains, was much more difficult.

The road came on Chinese maps published in 1958.

The McMahon Line

In 1826, British India gained a common border with China after the British wrested control of

Manipur and

Assam from the

Burmese

Burmese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Myanmar, a country in Southeast Asia

* Burmese people

* Burmese language

* Burmese alphabet

* Burmese cuisine

* Burmese culture

Animals

* Burmese cat

* Burmese chicken

* Burmese (hor ...

, following the

First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824–1826. In 1847, Major J. Jenkins, agent for the North East Frontier, reported that the Tawang was part of Tibet. In 1872, four monastic officials from Tibet arrived in Tawang and supervised a boundary settlement with Major R. Graham,

NEFA official, which included the Tawang Tract as part of Tibet. Thus, in the last half of the 19th century, it was clear that the British treated the Tawang Tract as part of Tibet. This boundary was confirmed in a 1 June 1912 note from the British General Staff in India, stating that the "present boundary (demarcated) is south of Tawang, running westwards along the foothills from near Udalguri, Darrang to the southern Bhutanese border and Tezpur claimed by China."

A 1908 map of The Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam prepared for the Foreign Department of the Government of India, showed the international boundary from Bhutan continuing to the Baroi River, following the Himalayas foothill alignment.

In 1913, representatives of the UK, China and Tibet attended a conference in

Simla regarding the borders between Tibet, China and British India. Whilst all three representatives initialed the agreement,

Beijing later objected to the proposed boundary between the regions of Outer Tibet and Inner Tibet, and did not ratify it. The details of the Indo-Tibetan boundary was not revealed to China at the time.

The foreign secretary of the British Indian government,

Henry McMahon, who had drawn up the proposal, decided to bypass the Chinese (although instructed not to by his superiors) and settle the border bilaterally by negotiating directly with Tibet.

According to later Indian claims, this border was intended to run through the highest ridges of the Himalayas, as the areas south of the Himalayas were traditionally Indian.

The McMahon Line lay south of the boundary India claims.

India's government held the view that the Himalayas were the ancient boundaries of the

Indian subcontinent, and thus should be the modern boundaries of India,

while it is the position of the Chinese government that the disputed area in the Himalayas have been geographically and culturally part of Tibet since ancient times.

Months after the

Simla agreement, China set up boundary markers south of the McMahon Line. T. O'Callaghan, an official in the Eastern Sector of the North East Frontier, relocated all these markers to a location slightly south of the McMahon Line, and then visited Rima to confirm with Tibetan officials that there was no Chinese influence in the area.

The British-run Government of India initially rejected the Simla Agreement as incompatible with the

Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which stipulated that neither party was to negotiate with Tibet "except through the intermediary of the Chinese government".

[Gupta, Karunakar, "The McMahon Line 1911–45: The British Legacy", ''The China Quarterly'', No. 47. (Jul. – Sep. 1971), pp. 521–45. ] The British and Russians cancelled the 1907 agreement by joint consent in 1921.

[Free Tibet Campaign,]

Tibet Facts No.17: British Relations with Tibet

It was not until the late 1930s that the British started to use the McMahon Line on official maps of the region.

China took the position that the Tibetan government should not have been allowed to make such a treaty, rejecting Tibet's claims of independent rule.

For its part, Tibet did not object to any section of the McMahon Line excepting the demarcation of the trading town of

Tawang, which the Line placed under British-Indian jurisdiction.

Up until

World War II, Tibetan officials were allowed to administer Tawang with complete authority. Due to the increased threat of Japanese and Chinese expansion during this period, British Indian troops secured the town as part of the defence of India's eastern border.

In the 1950s, India began patrolling the region. It found that, at multiple locations, the highest ridges actually fell north of the McMahon Line.

Given India's historic position that the original intent of the line was to separate the two nations by the highest mountains in the world, in these locations India extended its forward posts northward to the ridges, regarding this move as compliant with the original border proposal, although the Simla Convention did not explicitly state this intention.

Events leading up to war

Tibet and the border dispute

The 1940s saw huge change with the

Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

in 1947 (resulting in the establishment of the two new states of

India and

Pakistan), and the establishment of the

People's Republic of China (PRC) after the

Chinese Civil War in 1949. One of the most basic policies for the new Indian government was that of maintaining cordial relations with China, reviving its ancient friendly ties. India was among the first nations to grant diplomatic recognition to the newly created PRC.

At the time, Chinese officials issued no condemnation of Nehru's claims or made any opposition to Nehru's open declarations of control over Aksai Chin. In 1956,

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai stated that he had no claims over Indian-controlled territory.

He later argued that Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction and that the McCartney-MacDonald Line was the line China could accept.

Zhou later argued that as the boundary was undemarcated and had never been defined by treaty between any Chinese or Indian government, the Indian government could not unilaterally define Aksai Chin's borders.

In 1950, the Chinese

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, ...

(PLA)

invaded Tibet, which all Chinese governments regarded as still part of China. Later the Chinese extended their influence by building a road in 1956–67

and placing border posts in Aksai Chin.

India found out after the road was completed, protested against these moves and decided to look for a diplomatic solution to ensure a stable Sino-Indian border.

To resolve any doubts about the Indian position, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared in parliament that India regarded the McMahon Line as its official border.

The Chinese expressed no concern at this statement,

and in 1961 and 1962, the government of China asserted that there were no frontier issues to be taken up with India.

In 1954, Nehru wrote a memo calling for India's borders to be clearly defined and demarcated;

in line with previous Indian philosophy, Indian maps showed a border that, in some places, lay north of the McMahon Line.

[A.G. Noorani, "", ''India's National Magazine'', 29 August 2003.] Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, in November 1956, again repeated Chinese assurances that the People's Republic had no claims on Indian territory, although official Chinese maps showed of territory claimed by India as Chinese.

documents created at the time revealed that Nehru had ignored Burmese premier

Ba Swe when he warned Nehru to be cautious when dealing with Zhou.

[Chinese deception and Nehru's naivete led to 62 War](_blank)

''Times of India'' They also allege that Zhou purposefully told Nehru that there were no border issues with India.

In 1954, China and India negotiated the

Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, by which the two nations agreed to abide in settling their disputes. India presented a frontier map which was accepted by China, and the slogan ''Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai'' (Indians and Chinese are brothers) was popular then. Nehru in 1958 had privately told

G. Parthasarathi, the Indian envoy to China not to trust the Chinese at all and send all communications directly to him, bypassing the Defence Minister

VK Krishna Menon

Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon (3 May 1896 – 6 October 1974) was an Indian academic, politician, and non-career diplomat. He was described by some as the second most powerful man in India, after the first Prime Minister of India, Jawa ...

since his communist background clouded his thinking about China.

According to

Georgia Tech scholar , Nehru's policy on Tibet was to create a strong Sino-Indian partnership which would be catalysed through agreement and compromise on Tibet. Garver believes that Nehru's previous actions had given him confidence that China would be ready to form an "Asian Axis" with India.

This apparent progress in relations suffered a major setback when, in 1959, Nehru accommodated the Tibetan religious leader at the time, the

14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (spiritual name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, known as Tenzin Gyatso (Tibetan: བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: ''bsTan-'dzin rgya-mtsho''); né Lhamo Thondup), known as ...

, who fled

Lhasa after a failed

Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule. The

Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party

The Chairman of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party () was the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. The position was established at the 8th National Congress in 1945 and abolished at the 12th National Congress in 1982, bei ...

,

Mao Zedong, was enraged and asked the

Xinhua News Agency to produce reports on Indian expansionists operating in Tibet.

Border incidents continued through this period. In August 1959, the PLA took an Indian prisoner at Longju, which had an ambiguous position in the McMahon Line,

and two months later in Aksai Chin, a

clash at Kongka Pass led to the death of nine Indian frontier policemen.

On 2 October,

Soviet first secretary Nikita Khrushchev defended Nehru in a meeting with Mao. This action reinforced China's impression that the Soviet Union, the United States and India all had

expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

designs on China. The PLA went so far as to prepare a self-defence counterattack plan.

Negotiations were restarted between the nations, but no progress was made.

As a consequence of their non-recognition of the McMahon Line, China's maps showed both the North East Frontier Area (NEFA) and Aksai Chin to be Chinese territory.

In 1960, Zhou Enlai unofficially suggested that India drop its claims to Aksai Chin in return for a Chinese withdrawal of claims over NEFA. Adhering to his stated position, Nehru believed that China did not have a legitimate claim over either of these territories, and thus was not ready to concede them. This adamant stance was perceived in China as Indian opposition to Chinese rule in Tibet.

Nehru declined to conduct any negotiations on the boundary until Chinese troops withdrew from Aksai Chin, a position supported by the international community.

India produced numerous reports on the negotiations, and translated Chinese reports into English to help inform the international debate. China believed that India was simply securing its claim lines in order to continue its "grand plans in Tibet".

India's stance that China withdraw from Aksai Chin caused continual deterioration of the diplomatic situation to the point that internal forces were pressuring Nehru to take a military stance against China.

1960 meetings to resolve the boundary question

In 1960, based on an agreement between Nehru and Zhou Enlai, officials from India and China held discussions in order to settle the boundary dispute. China and India disagreed on the major watershed that defined the boundary in the western sector. The Chinese statements with respect to their border claims often misrepresented the cited sources. The failure of these negotiations was compounded by successful Chinese border agreements with Nepal (

Sino-Nepalese Treaty of Peace and Friendship

The Sino-Nepalese Treaty of Peace and Friendship was an official settlement between the governments of Nepal and China signed on 28 April 1960, which ratified an earlier agreement on the borders separating the neighboring nations from each other. ...

) and Burma in the same year.

The Forward Policy

In the summer of 1961, China began patrolling along the McMahon Line. They entered parts of Indian administered regions and much angered the Indians in doing so. The Chinese, however, did not believe they were intruding upon Indian territory. In response the Indians launched a policy of creating outposts behind the Chinese troops so as to cut off their supplies and force their return to China.

On 5 December 1961 orders went to the Eastern and Western commands:This has been referred to as the "Forward Policy".

There were eventually 60 such outposts, including 43 along the Chinese-claimed frontier in Aksai Chin.

Indian leaders believed, based on previous diplomacy, that the Chinese would not react with force.

According to the Indian Official History, Indian posts and Chinese posts were separated by a narrow stretch of land.

China had been steadily spreading into those lands and India reacted with the Forward Policy to demonstrate that those lands were not unoccupied.

Neville Maxwell traces this confidence to the Intelligene Bureau chief Mullik.

The initial reaction of the Chinese forces was to withdraw when Indian outposts advanced towards them.

However, this appeared to encourage the Indian forces to accelerate their Forward Policy even further.

In response, the Central Military Commission adopted a policy of "armed coexistence".

In response to Indian outposts encircling Chinese positions, Chinese forces would build more outposts to counter-encircle these Indian positions.

This pattern of encirclement and counter-encirclement resulted in an interlocking, chessboard-like deployment of Chinese and Indian forces.

Despite the leapfrogging encirclements by both sides, no hostile fire occurred from either side as troops from both sides were under orders to fire only in defense. On the situation, Mao commented,

Early incidents

Various border conflicts and "military incidents" between India and China flared up throughout the summer and autumn of 1962. In May, the

Indian Air Force

The Indian Air Force (IAF) is the air arm of the Indian Armed Forces. Its complement of personnel and aircraft assets ranks third amongst the air forces of the world. Its primary mission is to secure Indian airspace and to conduct aerial w ...

was told not to plan for

close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and moveme ...

, although it was assessed as being a feasible way to counter the unfavourable ratio of Chinese to Indian troops.

In June, a skirmish caused the deaths of dozens of Chinese troops. The Indian Intelligence Bureau received information about a Chinese buildup along the border which could be a precursor to war.

During June–July 1962, Indian military planners began advocating "probing actions" against the Chinese, and accordingly, moved mountain troops forward to cut off Chinese supply lines. According to Patterson, the Indian motives were threefold:

# Test Chinese resolve and intentions regarding India.

# Test whether India would enjoy Soviet backing in the event of a Sino-Indian war.

# Create sympathy for India within the U.S., with whom relations had deteriorated after

the Indian annexation of Goa.

On 10 July 1962, 350 Chinese troops surrounded an Indian post in Chushul (north of the McMahon Line) but withdrew after a heated argument via loudspeaker.

On 22 July, the Forward Policy was extended to allow Indian troops to push back Chinese troops already established in disputed territory.

[History of the Conflict with China, 1962. P.B. Sinha, A.A. Athale, with S.N. Prasad, chief editor, History Division, Ministry of Defence, Govt. of India, 1992.] Whereas Indian troops were previously ordered to fire only in self-defence, all post commanders were now given discretion to open fire upon Chinese forces if threatened.

In August, the Chinese military improved its combat readiness along the McMahon Line and began stockpiling ammunition, weapons and fuel.

Given his foreknowledge of the coming

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, Mao was able to persuade Khrushchev to reverse the Russian policy of backing India, at least temporarily.

In mid-October, the Communist organ ''

Pravda'' encouraged peace between India and China.

When the Cuban Missile Crisis ended and Mao's rhetoric changed, Russia reversed course.

Confrontation at Thagla Ridge

In June 1962, Indian forces established an outpost called the

Dhola Post on the northern slopes of Tsangdhar Range, in the right-side of

Namka Chu valley, facing the southern slopes of Thagla Ridge.

Clearly, The Dhola Post lay north of the map-marked McMahon Line which straight across Tsangdhar Range but south of Thagla Ridge along which India interpreted the McMahon Line to run.

[Manoj Joshi, "Line of Defence", ''Times of India'', 21 October 2000] In August, China issued diplomatic protests and began occupying positions at the top of Thagla Ridge.

On 8 September, a 60-strong PLA unit descended to the south side of the ridge and occupied positions that dominated one of the Indian posts at Namka Chu. Fire was not exchanged, but Nehru told the media that the Indian Army had instructions to "free our territory" and the troops had been given discretion to use force.

On 11 September, it was decided that "all forward posts and patrols were given permission to fire on any armed Chinese who entered Indian territory".

The operation to occupy Thagla Ridge was flawed in that Nehru's directives were unclear and it got underway very slowly because of this.

In addition to this, each man had to carry over the long trek and this severely slowed down the reaction.

By the time the Indian battalion reached the point of conflict, Chinese units controlled both banks of the Namka Chu River.

On 20 September, Chinese troops threw grenades at Indian troops and a firefight developed, triggering a long series of skirmishes for the rest of September.

Some Indian troops, including

Brigadier Dalvi who commanded the forces at Thagla Ridge, were also concerned that the territory they were fighting for was not strictly territory that "we should have been convinced was ours". According to Neville Maxwell, even members of the Indian defence ministry were categorically concerned with the validity of the fighting in Thagla Ridge.

On 4 October, Kaul assigned some troops to secure regions south of the Thagla Ridge.

Kaul decided to first secure Yumtso La, a strategically important position, before re-entering the lost Dhola Post.

Kaul had then realised that the attack would be desperate and the Indian government tried to stop an escalation into all-out war. Indian troops marching to Thagla Ridge had suffered in the previously unexperienced conditions; two

Gurkha soldiers died of

pulmonary edema.

On 10 October, an Indian

Rajput patrol of 50 troops to Yumtso La were met by an emplaced Chinese position of some 1,000 soldiers.

Indian troops were in no position for battle, as Yumtso La was above sea level and Kaul did not plan on having artillery support for the troops.

The Chinese troops opened fire on the Indians under their belief that they were north of the McMahon Line. The Indians were surrounded by Chinese positions which used

mortar fire. They managed to hold off the first Chinese assault, inflicting heavy casualties.

At this point, the Indian troops were in a position to push the Chinese back with mortar and machine gun fire. Brigadier Dalvi opted not to fire, as it would mean decimating the Rajput who were still in the area of the Chinese regrouping. They helplessly watched the Chinese ready themselves for a second assault.

In the second Chinese assault, the Indians began their retreat, realising the situation was hopeless. The Indian patrol suffered 25 casualties and the Chinese 33. The Chinese troops held their fire as the Indians retreated, and then buried the Indian dead with military honours, as witnessed by the retreating soldiers. This was the first occurrence of heavy fighting in the war.

This attack had grave implications for India and Nehru tried to solve the issue, but by 18 October, it was clear that the Chinese were preparing for an attack, with a massive troop buildup.

A long line of mules and porters had also been observed supporting the buildup and reinforcement of positions south of the Thagla Ridge.

Chinese preparations

Chinese motives

Two of the major factors leading up to China's eventual conflicts with Indian troops were India's stance on the disputed borders and perceived Indian subversion in Tibet. There was "a perceived need to punish and end perceived Indian efforts to undermine Chinese control of Tibet, Indian efforts which were perceived as having the objective of restoring the pre-1949 status quo ante of Tibet". The other was "a perceived need to punish and end perceived Indian aggression against Chinese territory along the border". John W. Garver argues that the first perception was incorrect based on the state of the Indian military and polity in the 1960s. It was, nevertheless a major reason for China's going to war. He argues that while the Chinese perception of Indian border actions were "substantially accurate", Chinese perceptions of the supposed Indian policy towards Tibet were "substantially inaccurate".

The CIA's declassified POLO documents reveal contemporary American analysis of Chinese motives during the war. According to this document, "Chinese apparently were motivated to attack by one primary consideration — their determination to retain the ground on which PLA forces stood in 1962 and to punish the Indians for trying to take that ground". In general terms, they tried to show the Indians once and for all that China would not acquiesce in a military "reoccupation" policy. Secondary reasons for the attack were to damage Nehru's prestige by exposing Indian weakness and

to expose as traitorous Khrushchev's policy of supporting Nehru against a Communist country.

Another factor which might have affected China's decision for war with India was a perceived need to stop a Soviet-U.S.-India encirclement and isolation of China.

India's relations with the Soviet Union and United States were both strong at this time, but the Soviets (and Americans) were preoccupied by the Cuban Missile Crisis and would not interfere with the Sino-Indian War.

P. B. Sinha suggests that China waited until October to attack because the timing of the war was exactly in parallel with American actions so as to avoid any chance of American or Soviet involvement. Although American buildup of forces around Cuba occurred on the same day as the first major clash at Dhola Post, and China's buildup between 10 and 20 October appeared to coincide exactly with the United States establishment of a blockade against Cuba which began 20 October, the Chinese probably prepared for this before they could anticipate what would happen in Cuba.

In May to June 1962, the KMT government of

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

on Taiwan under

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

's leadership was propagating the policy of 'Reclaim the

mainland China', causing fear of invasion from Taiwan among Chinese Communist leadership and the shift of concern to the Southeast. Reluctant to divert resources to the hostitlies in the Himalayas, Chinese leadership thought a two-front war undesirable. From July on, after receiving American assurances that KMT government would not invade, China began to focus on the Indian border.

Garver argues that the Chinese correctly assessed Indian border policies, particularly the Forward Policy, as attempts for incremental seizure of Chinese-controlled territory. On Tibet, Garver argues that one of the major factors leading to China's decision for war with India was a common tendency of humans "to attribute others' behavior to interior motivations, while attributing their own behavior to situational factors". Studies from China published in the 1990s confirmed that the root cause for China going to war with India was the perceived Indian aggression in Tibet, with the forward policy simply catalysing the Chinese reaction.

Neville Maxwell and

Allen Whiting argue that the Chinese leadership believed they were defending territory that was legitimately Chinese, and which was already under de facto Chinese occupation prior to Indian advances, and regarded the Forward Policy as an Indian attempt at creeping annexation.

Mao Zedong himself compared the Forward Policy to a strategic advance in

Chinese chess:

Chinese policy toward India, therefore, operated on two seemingly contradictory assumptions in the first half of 1961. On the one hand, the Chinese leaders continued to entertain a hope, although a shrinking one, that some opening for talks would appear. On the other hand, they read Indian statements and actions as clear signs that Nehru wanted to talk only about a Chinese withdrawal. Regarding the hope, they were willing to negotiate and tried to prod Nehru into a similar attitude. Regarding Indian intentions, they began to act politically and to build a rationale based on the assumption that Nehru already had become a lackey of imperialism; for this reason he opposed border talks.

Krishna Menon is reported to have said that when he arrived in Geneva on 6 June 1961 for an international conference in Laos, Chinese officials in Chen Yi's delegation indicated that Chen might be interested in discussing the border dispute with him. At several private meetings with Menon, Chen avoided any discussion of the dispute and Menon surmised that the Chinese wanted him to broach the matter first. He did not, as he was under instructions from Nehru to avoid taking the initiative, leaving the Chinese with the impression that Nehru was unwilling to show any flexibility.

In September, the Chinese took a step toward criticising Nehru openly in their commentary. After citing Indonesian and Burmese press criticism of Nehru by name, the Chinese critiqued his moderate remarks on colonialism (People's Daily Editorial, 9 September): "Somebody at the Non-Aligned Nations Conference advanced the argument that the era of classical colonialism is gone and dead...contrary to facts." This was a distortion of Nehru's remarks but appeared close enough to be credible. On the same day, Chen Yi referred to Nehru by implication at the Bulgarian embassy reception: "Those who attempted to deny history, ignore reality, and distort the truth and who attempted to divert the Conference from its important object have failed to gain support and were isolated." On 10 September, they dropped all circumlocutions and criticised him by name in a China Youth article and NCNA report—the first time in almost two years that they had commented extensively on the Prime Minister.

By early 1962, the Chinese leadership began to believe that India's intentions were to launch a massive attack against Chinese troops, and that the Indian leadership wanted a war.

In 1961, the Indian Army had been sent into

Goa, a small region without any other international borders apart from the Indian one, after

Portugal refused to surrender the

exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

colony to the Indian Union. Although this action met little to no international protest or opposition, China saw it as an example of India's expansionist nature, especially in light of heated rhetoric from Indian politicians. India's Home Minister declared, "If the Chinese will not vacate the areas occupied by it, India will have to repeat

what it did in Goa. India will certainly drive out the Chinese forces",

while another member of the Indian Congress Party pronounced, "India will take steps to end

hineseaggression on Indian soil just as it ended Portuguese aggression in Goa".

By mid-1962, it was apparent to the Chinese leadership that negotiations had failed to make any progress, and the Forward Policy was increasingly perceived as a grave threat as

Delhi increasingly sent probes deeper into border areas and cut off Chinese supply lines.

Foreign Minister

Marshal Chen Yi commented at one high-level meeting, "Nehru's forward policy is a knife. He wants to put it in our heart. We cannot close our eyes and await death."

The Chinese leadership believed that their restraint on the issue was being perceived by India as weakness, leading to continued provocations, and that a major counterblow was needed to stop perceived Indian aggression.

Xu Yan, prominent Chinese military historian and professor at the PLA's

National Defense University, gives an account of the Chinese leadership's decision to go to war. By late September 1962, the Chinese leadership had begun to reconsider their policy of "armed coexistence", which had failed to address their concerns with the forward policy and Tibet, and consider a large, decisive strike.

On 22 September 1962, the ''

People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' () is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The newspaper provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP. In addition to its main Chinese-language ...

'' published an article which claimed that "the Chinese people were

burning with 'great indignation' over the Indian actions on the border and that New Delhi could not 'now say that warning was not served in advance'."

['']People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' () is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The newspaper provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP. In addition to its main Chinese-language ...

'', 22 September 1962 issue, pp. 1

Military planning

The Indian side was confident war would not be triggered and made little preparations. India had only two divisions of troops in the region of the conflict.

In August 1962, Brigadier D. K. Palit claimed that a war with China in the near future could be ruled out.

Even in September 1962, when Indian troops were ordered to "expel the Chinese" from Thagla Ridge, Maj. General J. S. Dhillon expressed the opinion that "experience in Ladakh had shown that a few rounds fired at the Chinese would cause them to run away."

Because of this, the Indian Army was completely unprepared when the attack at Yumtso La occurred.

Declassified CIA documents which were compiled at the time reveal that India's estimates of Chinese capabilities made them neglect their military in favour of economic growth.

[China feared military coup in India during 60s](_blank)

''DNA India'' It is claimed that if a more military-minded man had been in place instead of Nehru, India would have been more likely to have been ready for the threat of a counter-attack from China.

On 6 October 1962, the Chinese leadership convened.

Lin Biao reported that PLA intelligence units had determined that Indian units might assault Chinese positions at Thagla Ridge on 10 October (Operation Leghorn). The Chinese leadership and the Central Military Council decided upon war to launch a large-scale attack to punish perceived military aggression from India.

In Beijing, a larger meeting of Chinese military was convened in order to plan for the coming conflict.

Mao and the Chinese leadership issued a directive laying out the objectives for the war. A main assault would be launched in the eastern sector, which would be coordinated with a smaller assault in the western sector. All Indian troops within China's claimed territories in the eastern sector would be expelled, and the war would be ended with a unilateral Chinese ceasefire and withdrawal, followed by a return to the negotiating table.

India led the

Non-Aligned Movement, Nehru enjoyed international prestige, and China, with a larger military, would be portrayed as an aggressor. He said that a well-fought war "will guarantee at least thirty years of peace" with India, and determined the benefits to offset the costs.

China also reportedly bought a significant amount of Indian rupee currency from

Hong Kong, supposedly to distribute amongst its soldiers in preparation for the war.

On 8 October, additional veteran and elite divisions were ordered to prepare to move into Tibet from the

Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; Simplified Chinese characters, simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively Romanization of Chi ...

and

Lanzhou

Lanzhou (, ; ) is the capital and largest city of Gansu Province in Northwest China. Located on the banks of the Yellow River, it is a key regional transportation hub, connecting areas further west by rail to the eastern half of the country. H ...

military regions.

On 14 October, an editorial on ''People's Daily'' issued China's final warning to India: "So it seems that Mr. Nehru has made up his mind to attack the Chinese frontier guards on an even bigger scale. ... It is high time to shout to Mr. Nehru that the heroic Chinese troops, with the glorious tradition of resisting foreign aggression, can never be cleared by anyone from their own territory ... If there are still some maniacs who are reckless enough to ignore our well-intentioned advice and insist on having another try, well, let them do so. History will pronounce its inexorable verdict ... At this critical moment ... we still want to appeal once more to Mr. Nehru: better rein in at the edge of the precipice and do not use the lives of Indian troops as stakes in your gamble."

Marshal

Liu Bocheng headed a group to determine the strategy for the war. He concluded that the opposing Indian troops were among India's best, and to achieve victory would require deploying crack troops and relying on

force concentration to achieve decisive victory. On 16 October, this war plan was approved, and on the 18th, the final approval was given by the Politburo for a "self-defensive counter-attack", scheduled for 20 October.

Chinese offensive

On 20 October 1962, the PLA launched two attacks, apart. In the western theatre, the PLA sought to expel Indian forces from the Chip Chap valley in Aksai Chin while in the eastern theatre, the PLA sought to capture both banks of the Namka Chu river. Some skirmishes also took place at the

Nathula Pass

Nathu La

(, ) is a mountain pass in the Dongkya Range of the Himalayas between China's Yadong County in Tibet, and the Indian states of Sikkim and West Bengal in Bengal, South Asia. The pass, at , connects the towns of Kalimpong and Gangtok ...

, which is in the Indian state of Sikkim (an Indian protectorate at that time). Gurkha rifles travelling north were targeted by Chinese artillery fire. After four days of fierce fighting, the three

regiments of Chinese troops succeeded in securing a substantial portion of the disputed territory.

Eastern theatre

Chinese troops launched an attack on the southern banks of the Namka Chu River on 20 October.

The Indian forces were undermanned, with only an understrength battalion to support them, while the Chinese troops had three regiments positioned on the north side of the river.

The Indians expected Chinese forces to cross via one of five bridges over the river and defended those crossings.

The PLA bypassed the defenders by fording the river, which was shallow at that time of year, instead. They formed up into battalions on the Indian-held south side of the river under cover of darkness, with each battalion assigned against a separate group of Rajputs.

At 5:14 am, Chinese mortar fire began attacking the Indian positions. Simultaneously, the Chinese cut the Indian telephone lines, preventing the defenders from making contact with their headquarters. At about 6:30 am, the Chinese infantry launched a surprise attack from the rear and forced the Indians to leave their trenches.

The Chinese overwhelmed the Indian troops in a series of flanking manoeuvres south of the McMahon Line and prompted their withdrawal from Namka Chu.

Fearful of continued losses, Indian troops retreated into Bhutan. Chinese forces respected the border and did not pursue.

Chinese forces now held all of the territory that was under dispute at the time of the Thagla Ridge confrontation, but they continued to advance into the rest of NEFA.

On 22 October, at 12:15 am, PLA mortars fired on

Walong, on the McMahon line.

Flares launched by Indian troops the next day revealed numerous Chinese milling around the valley.

The Indians tried to use their mortars against the Chinese but the PLA responded by lighting a bush fire, causing confusion among the Indians. Some 400 PLA troops attacked the Indian position. The initial Chinese assault was halted by accurate Indian mortar fire. The Chinese were then reinforced and launched a second assault. The Indians managed to hold them back for four hours, but the Chinese used weight of numbers to break through. Most Indian forces were withdrawn to established positions in Walong, while a company supported by mortars and medium machine guns remained to cover the retreat.

Elsewhere, Chinese troops launched a three-pronged attack on Tawang, which the Indians evacuated without any resistance.

Over the following days, there were clashes between Indian and Chinese patrols at Walong as the Chinese rushed in reinforcements. On 25 October, the Chinese made a probe, which was met with resistance from the 4th Sikhs. The following day, a patrol from the 4th Sikhs was encircled, and after being unable to break the encirclement, an Indian unit was able to flank the Chinese, allowing the Sikhs to break free.

Western theatre

On the Aksai Chin front, China already controlled most of the disputed territory. Chinese forces quickly swept the region of any remaining Indian troops. Late on 19 October, Chinese troops launched a number of attacks throughout the western theatre.

By 22 October, all posts north of Chushul had been cleared.

On 20 October, the Chinese easily took the Chip Chap Valley, Galwan Valley and Pangong Lake.

Many outposts and garrisons along the Western front were unable to defend against the surrounding Chinese troops. Most Indian troops positioned in these posts offered resistance but were either killed or taken prisoner. Indian support for these outposts was not forthcoming, as evidenced by the Galwan post, which had been surrounded by enemy forces in August, but no attempt made to relieve the besieged garrison. Following the 20 October attack, nothing was heard from Galwan.

On 24 October, Indian forces fought hard to hold the Rezang La Ridge, in order to prevent a nearby airstrip from falling.

[Men of Steel on Icy Heights](_blank)

Mohan Guruswamy ''Deccan Chronicle''.

After realising the magnitude of the attack, the Indian Western Command withdrew many of the isolated outposts to the south-east. Daulet Beg Oldi was also evacuated, but it was south of the Chinese claim line and was not approached by Chinese forces. Indian troops were withdrawn in order to consolidate and regroup in the event that China probed south of their claim line.

Lull in the fighting

By 24 October, the PLA had entered territory previously administered by India to give the PRC a diplomatically strong position over India. The majority of Chinese forces had advanced south of the control line prior to the conflict. Four days of fighting were followed by a three-week lull. Zhou ordered the troops to stop advancing as he attempted to negotiate with Nehru. The Indian forces had retreated into more heavily fortified positions around Se La and Bomdi La which would be difficult to assault.

Zhou sent Nehru a letter, proposing

# A negotiated settlement of the boundary

# That both sides disengage and withdraw from present lines of actual control

# A Chinese withdrawal north in NEFA

# That China and India not cross lines of present control in Aksai Chin.

Nehru's 27 October reply expressed interest in the restoration of peace and friendly relations and suggested a return to the "boundary prior to 8 September 1962". He was categorically concerned about a mutual withdrawal after "40 or 60 kilometres (25 or 40 miles) of blatant military aggression". He wanted the creation of a larger immediate buffer zone and thus resist the possibility of a repeat offensive. Zhou's 4 November reply repeated his 1959 offer to return to the McMahon Line in NEFA and the Chinese traditionally claimed MacDonald Line in Aksai Chin. Facing Chinese forces maintaining themselves on Indian soil and trying to avoid political pressure, the Indian parliament announced a national emergency and passed a resolution which stated their intent to "drive out the aggressors from the sacred soil of India". The United States and the United Kingdom supported India's response. The Soviet Union was preoccupied with the Cuban Missile Crisis and did not offer the support it had provided in previous years. With the backing of other

great powers, a 14 November letter by Nehru to Zhou once again rejected his proposal.

Neither side declared war, used their air force, or fully broke off diplomatic relations, but the conflict is commonly referred to as a war. This war coincided with the Cuban Missile Crisis and was viewed by the western nations at the time as another act of aggression by the Communist bloc.

According to Calvin, the Chinese side evidently wanted a diplomatic resolution and discontinuation of the conflict.

Continuation of war

After Zhou received Nehru's letter (rejecting Zhou's proposal), the fighting resumed on the eastern theatre on 14 November (Nehru's birthday), with an Indian attack on Walong, claimed by China, launched from the defensive position of Se La and inflicting heavy casualties on the Chinese. The Chinese resumed military activity on Aksai Chin and NEFA hours after the Walong battle.

Continuation of Eastern theatre

In the eastern theatre, the PLA attacked Indian forces near

Se La and

Bomdi La on 17 November. These positions were defended by the

Indian 4th Infantry Division

The 4th Indian Infantry Division, also known as the Red Eagle Division, is an infantry division of the Indian Army. This division of the British Indian Army was formed in Egypt in 1939 during the Second World War. During the Second World War, ...

. Instead of attacking by road as expected, PLA forces approached via a mountain trail, and their attack cut off a main road and isolated 10,000 Indian troops.

Se La occupied high ground, and rather than assault this commanding position, the Chinese captured

Thembang

Thembang is an ancient village with high historical and cultural significance situated in West Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh, India.

History

Thembang is an ancient village, which was said to be established before first century AD. The vi ...

, which was a supply route to Se La.

The PLA penetrated close to the outskirts of

Tezpur, Assam, a major frontier town nearly from the Assam-North-East Frontier Agency border.

The local government ordered the evacuation of the civilians in Tezpur to the south of the

Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra is a trans-boundary river which flows through Tibet, northeast India, and Bangladesh. It is also known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, the Siang/Dihang River in Arunachali, Luit in Assamese, and Jamuna River in Bangla. It ...

, all prisons were thrown open, and government officials who stayed behind destroyed Tezpur's currency reserves in anticipation of a Chinese advance.

Continuation of Western theatre

On the western theatre, PLA forces launched a heavy infantry attack on 18 November near Chushul. Their attack started at 4:35 am, despite a mist surrounding most of the areas in the region. At 5:45 the Chinese troops advanced to attack two

platoons of Indian troops at

Gurung Hill

Gurung Hill is a mountain near the Line of Actual Control between the Indian- and Chinese-administered portions of Ladakh near the village of Chushul and the Spanggur Lake. As of 2020, the Line of Actual Control runs on the north–south ridgeli ...

.

The Indians did not know what was happening, as communications were dead. As a patrol was sent, China attacked with greater numbers. Indian artillery could not hold off the superior Chinese forces. By 9:00 am, Chinese forces attacked Gurung Hill directly and Indian commanders withdrew from the area and also from the connecting

Spangur Gap

Spanggur Tso, also called Maindong Tso, Mendong Tso, is a saltwater lake in Rutog County in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, close to the border with Ladakh. India claims a major portion of the lake as its own territory, as part of Ladakh. T ...

.

The Chinese had been simultaneously attacking Rezang La which was held by 123 Indian troops. At 5:05 am, Chinese troops launched their attack audaciously. Chinese medium machine gun fire pierced through the Indian tactical defences.

At 6:55 am the sun rose and the Chinese attack on the 8th platoon began in waves. Fighting continued for the next hour, until the Chinese signaled that they had destroyed the 7th platoon. Indians tried to use light machine guns on the medium machine guns from the Chinese but after 10 minutes the battle was over.

Logistical inadequacy once again hurt the Indian troops.

[YADAV, Atul]

Injustice to the Ahir Martyrs of the 1962 War

Bharat Rakshak, The Tribune. 18 November 1999 The Chinese gave the Indian troops a respectful military funeral.

The battles also saw the death of

Major Shaitan Singh of the

Kumaon Regiment, who had been instrumental in the first battle of Rezang La.

The Indian troops were forced to withdraw to high mountain positions. Indian sources believed that their troops were just coming to grips with the mountain combat and finally called for more troops. The Chinese declared a ceasefire, ending the bloodshed.

Indian forces suffered heavy casualties, with dead Indian troops' bodies being found in the ice, frozen with weapons in hand. The Chinese forces also suffered heavy casualties, especially at Rezang La. This signalled the end of the war in Aksai Chin as China had reached their claim line – many Indian troops were ordered to withdraw from the area. China claimed that the Indian troops wanted to fight on until the bitter end. The war ended with their withdrawal, so as to limit the number of casualties.

Ceasefire

China had reached its claim lines so the PLA did not advance farther, and on 19 November, it declared a unilateral

cease-fire. Zhou Enlai declared a unilateral ceasefire to start on midnight, 21 November. Zhou's ceasefire declaration stated,

Zhou had first given the ceasefire announcement to Indian chargé d'affaires on 19 November (before India's request for United States air support), but New Delhi did not receive it until 24 hours later. The aircraft carrier was ordered back after the ceasefire, and thus, American intervention on India's side in the war was avoided. Retreating Indian troops, who hadn't come into contact with anyone knowing of the ceasefire, and Chinese troops in NEFA and Aksai Chin, were involved in some minor battles,

but for the most part, the ceasefire signalled an end to the fighting. The

United States Air Force flew in supplies to India in November 1962, but neither side wished to continue hostilities.

Toward the end of the war India increased its support for Tibetan refugees and revolutionaries, some of them having settled in India, as they were fighting the same common enemy in the region. The Nehru administration ordered the raising of an elite Indian-trained "

Tibetan Armed Force" composed of Tibetan refugees.

International reactions

According to James Calvin, western nations at the time viewed China as an aggressor during the China–India border war, and saw the war as part of a monolithic communist objective for a world

dictatorship of the proletariat. This was further triggered by Mao's statement that: "the way to world conquest lies through Havana, Accra and Calcutta".

The United States was unequivocal in its recognition of the Indian boundary claims in the eastern sector, while not supporting the claims of either side in the western sector.

Britain, on the other hand, agreed with the Indian position completely, with the foreign secretary stating, 'we have taken the view of the government of India on the present frontiers and the disputed territories belong to India.'

The Chinese military action has been viewed by the United States as part of the PRC's policy of making use of aggressive wars to settle its border disputes and to distract both its own population and international opinion from its

internal issues. The

Kennedy

Kennedy may refer to:

People

* John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), 35th president of the United States

* John Kennedy (Louisiana politician), (born 1951), US Senator from Louisiana

* Kennedy (surname), a family name (including a list of persons with t ...

administration was disturbed by what they considered "blatant Chinese communist aggression against India". In a May 1963

National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a na ...

meeting, contingency planning on the part of the United States in the event of another Chinese attack on India was discussed and nuclear options were considered.

After listening to advisers, Kennedy stated "We should defend India, and therefore we will defend India."

By 1964, China had developed its own nuclear weapon which would have likely caused any American nuclear policy in defense of India to be reviewed.

The non-aligned nations remained mostly uninvolved, and only Egypt (officially the

United Arab Republic) openly supported India.

Of the non-aligned nations, six,

Egypt, Burma,

Cambodia,

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

,

Ghana and

Indonesia, met in

Colombo on 10 December 1962.

The proposals stipulated a Chinese withdrawal of from the customary lines without any reciprocal withdrawal on India's behalf.

The failure of these six nations to unequivocally condemn China deeply disappointed India.

Pakistan also shared a disputed boundary with China, and had proposed to India that the two countries adopt a common defence against "northern" enemies (i.e. China), which was rejected by India, citing nonalignment.

In 1962, President of Pakistan

Ayub Khan

Ayub Khan is a compound masculine name; Ayub is the Arabic version of the name of the Biblical figure Job, while Khan or Khaan is taken from the title used first by the Mongol rulers and then, in particular, their Islamic and Persian-influenced s ...

made clear to India that Indian troops could safely be transferred from the Pakistan frontier to the Himalayas. But, after the war, Pakistan improved its relations with China.

It began border negotiations on 13 October 1962, concluding them in December of that year.

The following year, the China-Pakistan Border Treaty was signed, as well as trade, commercial, and barter treaties.

Pakistan conceded its northern claim line in

Pakistani-controlled Kashmir to China in favour of a more southerly boundary along the Karakoram Range.

The border treaty largely set the border along the MacCartney-Macdonald Line.

India's military failure against China would embolden Pakistan to initiate the

Second Kashmir War with India in 1965.

Foreign involvement

During the conflict, Nehru wrote two letters on 19 November 1962 to U.S. President Kennedy, asking for 12 squadrons of fighter jets and a modern radar system. These jets were seen as necessary to beef up Indian air strength so that air-to-air combat could be initiated safely from the Indian perspective (bombing troops was seen as unwise for fear of Chinese retaliatory action). Nehru also asked that these aircraft be manned by American pilots until Indian airmen were trained to replace them. These requests were rejected by the Kennedy Administration (which was involved in the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

during most of the Sino-Indian War). The U.S. nonetheless provided non-combat assistance to Indian forces and planned to send the carrier to the

Bay of Bengal to support India in case of an air war.

As the

Sino-Soviet split had already emerged,

Moscow, while remaining formally neutral, made a major effort to render military assistance to India, especially with the sale of advanced MiG warplanes. The U.S. and Britain refused to sell these advanced weapons so India turned to the USSR. India and the USSR reached an agreement in August 1962 (before the Cuban Missile Crisis) for the immediate purchase of twelve

MiG-21s as well as for Soviet technical assistance in the manufacture of these aircraft in India. According to P.R. Chari, "The intended Indian production of these relatively sophisticated aircraft could only have incensed Peking so soon after the withdrawal of Soviet technicians from China." In 1964 further Indian requests for American jets were rejected. However, Moscow offered loans, low prices and technical help in upgrading India's armaments industry. India by 1964 was a major purchaser of Soviet arms. According to Indian diplomat

G. Parthasarathy

Captain Gopalaswami Parthasarathy, popularly known as G. Parthasarathy (born 13 May 1940) is a former commissioned officer in the Indian Army (1963-1968) and a diplomat and author. He has served as the High Commissioner of India, Cyprus (199 ...

, "only after we got nothing from the US did arms supplies from the Soviet Union to India commence." India's favored relationship with Moscow continued into the 1980s, but ended after the collapse of Soviet Communism in 1991. In his memoirs, the then Soviet leader,

Nikita Khrushchev, says: "I think Mao created the Sino-Indian conflict precisely in order to draw the Soviet Union into it. He wanted to put us in the position of having to no choice but to support him. He wanted to be the one who decided what we should do. But Mao made a mistake in thinking we would agree to sacrifice our independence in foreign policy."

Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev st ...

; Edward Crankshaw

Edward Crankshaw (3 January 1909 – 30 November 1984) was a British writer, author, translator and commentator; best known for his work on Soviet Union, Soviet affairs and the Gestapo (Secret State Police) of Nazi Germany.

Biography

William Edw ...

; Strobe Talbott

Nelson Strobridge Talbott III (born April 25, 1946) is an American foreign policy analyst focused on Russia. He was associated with ''Time'' magazine, and a diplomat who served as the Deputy Secretary of State from 1994 to 2001. He was president ...

; Jerrold L Schecter. Khrushchev remembers (volume 2): the last testament. London: Deutsch, 1974, p. 364.

Aftermath

China

According to the China's official military history, the war achieved China's policy objectives of securing borders in its western sector, as China retained de facto control of the Aksai Chin. After the war, India abandoned the Forward Policy, and the de facto borders stabilised along the

Line of Actual Control.

According to James Calvin, even though China won a military victory it lost in terms of its international image.

China's first nuclear weapon

test in October 1964 and its support of Pakistan in the

1965 India Pakistan War

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 or the Second Kashmir War was a culmination of skirmishes that took place between April 1965 and September 1965 between Pakistan and India. The conflict began following Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was d ...

tended to confirm the American view of communist world objectives, including Chinese influence over Pakistan.

Lora Saalman opined in a study of Chinese military publications, that while the war led to much blame, debates and ultimately acted as causation of military modernisation of India but the war is now treated as basic reportage of facts with relatively diminished interest by Chinese analysts.

India

The aftermath of the war saw sweeping changes in the Indian military to prepare it for similar conflicts in the future, and placed pressure on Nehru, who was seen as responsible for failing to anticipate the Chinese attack on India. Indians reacted with a surge in patriotism and memorials were erected for many of the Indian troops who died in the war. Arguably, the main lesson India learned from the war was the need to strengthen its own defences and a shift from Nehru's foreign policy with China based on his stated concept of "brotherhood". Because of India's inability to anticipate Chinese aggression, Nehru faced harsh criticism from government officials, for having promoted pacifist relations with China.

Indian President

Radhakrishnan said that Nehru's government was naive and negligent about preparations, and Nehru admitted his failings.

According to Inder Malhotra, a former editor of ''The Times of India'' and a commentator for ''The Indian Express'', Indian politicians invested more effort in removing Defence Minister

Krishna Menon than in actually waging war.

Menon's favoritism weakened the Indian Army, and national morale dimmed.

The public saw the war as a political and military debacle.

Under American advice (by American envoy

John Kenneth Galbraith who made and ran American policy on the war as all other top policy makers in the US were absorbed in coincident Cuban Missile Crisis) Indians refrained, not according to the best choices available, from using the

Indian air force

The Indian Air Force (IAF) is the air arm of the Indian Armed Forces. Its complement of personnel and aircraft assets ranks third amongst the air forces of the world. Its primary mission is to secure Indian airspace and to conduct aerial w ...

to beat back the Chinese advances. The CIA later revealed that at that time the Chinese had neither the fuel nor runways long enough for using their air force effectively in Tibet.

Indians in general became highly sceptical of China and its military. Many Indians view the war as a betrayal of India's attempts at establishing a long-standing peace with China and started to question the once popular "Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai" (meaning "Indians and Chinese are brothers"). The war also put an end to Nehru's earlier hopes that India and China would form a strong Asian Axis to counteract the increasing influence of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

bloc superpowers.

The unpreparedness of the army was blamed on Defence Minister Menon, who resigned his government post to allow for someone who might modernise India's military. India's policy of weaponisation via indigenous sources and self-sufficiency was thus cemented. Sensing a weakened army, Pakistan, a close ally of China, began a policy of provocation against India by

infiltrating Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

and ultimately triggering the Second Kashmir War with India in 1965 and

Indo-Pakistani war of 1971. The attack of 1965 was successfully stopped and ceasefire was negotiated under international pressure. In the Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 India won a clear victory, resulting in liberation of Bangladesh (formerly East-Pakistan).

As a result of the war, the Indian government commissioned an investigation, resulting in the classified