Siege Of Oxford (1646) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Oxford comprised the

Late in May 1644

Late in May 1644

Oxford Crown

''Siege of Oxford'' (1646)

painting by Jan de Wyck.

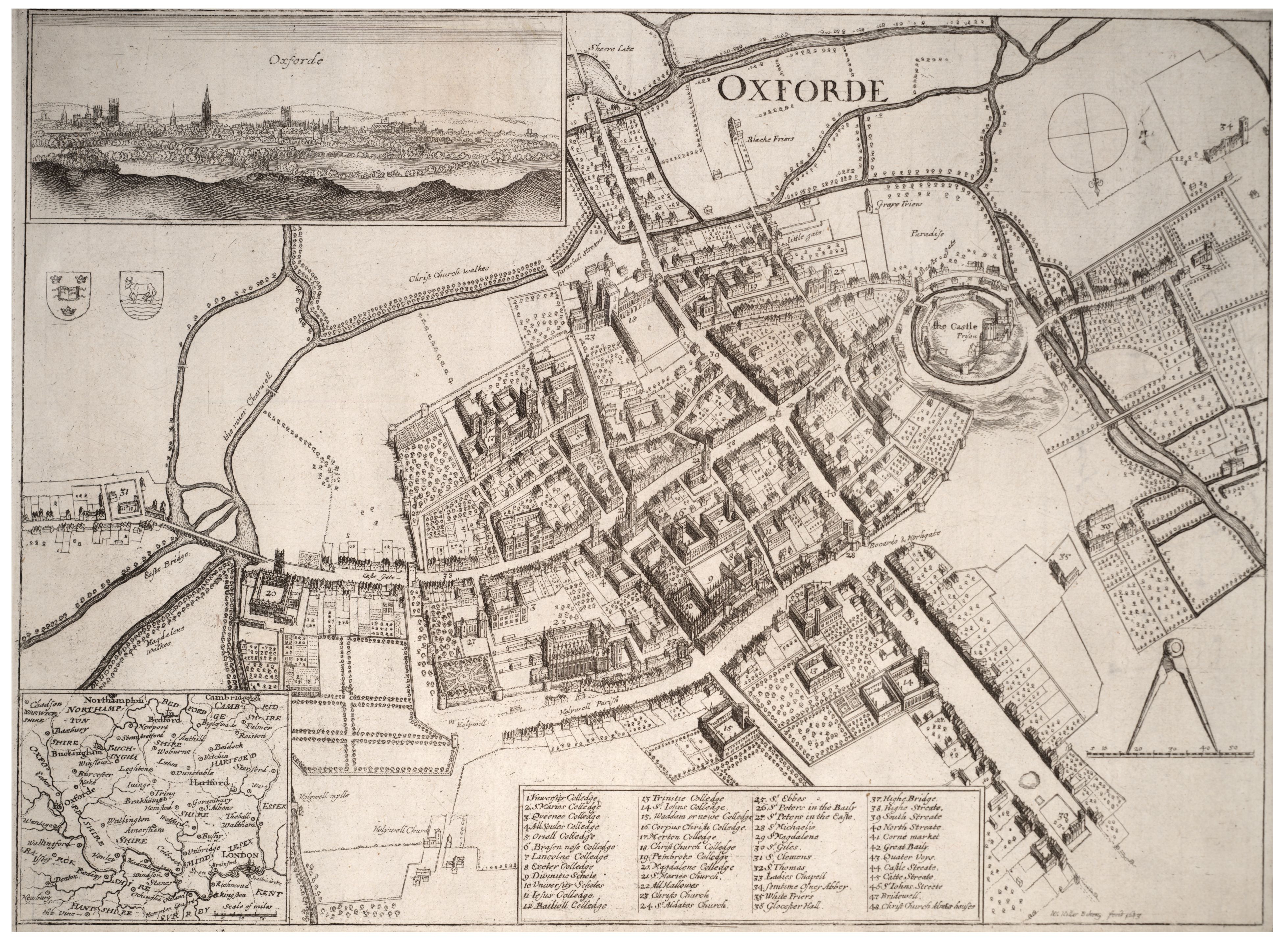

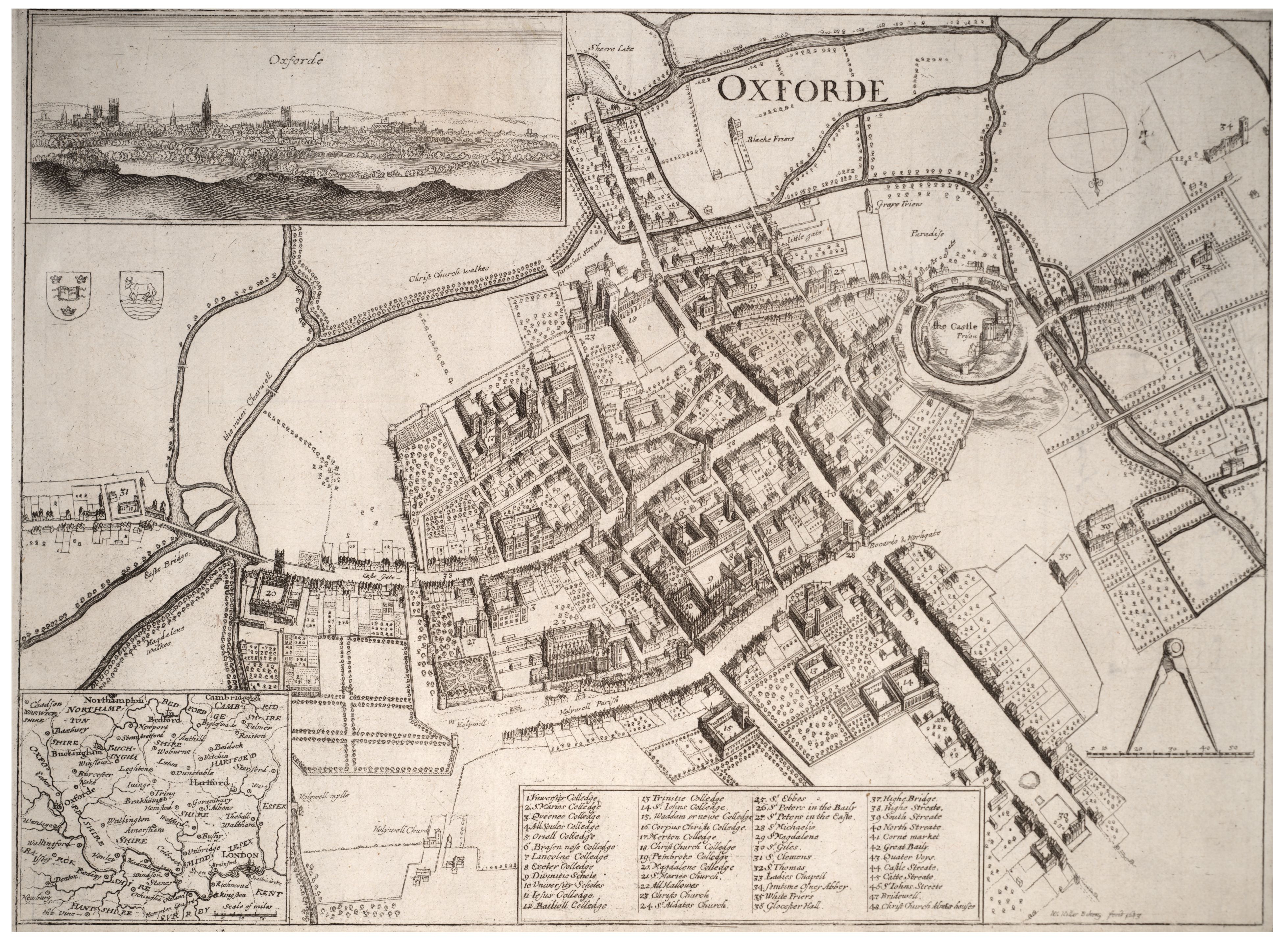

Reproduction of a 1644 map of the defences of Oxford

by

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

military campaigns waged to besiege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

controlled city of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, involving three short engagements over twenty-five months, which ended with a Parliamentarian victory in June 1646.

The first engagement was in May 1644, during which King Charles I escaped, thus preventing a formal siege. The second, in May 1645, had barely started when Sir Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

was given orders to stop and pursue the King to Naseby

Naseby is a village in West Northamptonshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 Census was 687.

The village is 14 mi (22.5 km) north of Northampton, 13.3 mi (21.4 km) northeast of Daventry, and 7&nb ...

instead. The last siege began in May 1646 and was a formal siege of two months; but the war was obviously over and negotiation, rather than fighting, took precedence. Being careful not to inflict too much damage on the city, Fairfax even sent in food to the King's second son, James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguati ...

, and was happy to conclude the siege with an honourable agreement before any further escalation occurred.

Oxford during the civil war

The creation of the King's Oxford Parliament in January 1644 placed Oxford at the centre of the Cavalier cause and the city became the headquarters of the King's forces. This had advantages and disadvantages for both parties; although the majority of citizens supported the Roundheads, supplying the Royalist court and garrison gave them financial opportunities. The location of Oxford gave the King the strategic advantage in controlling the Midland counties but the disadvantages of the city became increasingly manifest. Despite this, any proposals to retreat to the southwest were silenced, particularly by those enjoying the comforts of university accommodation. The King was at Christ Church and the Queen at Merton. The executive committee of the Privy Council met at Oriel; St John's housed the French ambassador and the two Palatine princes Rupert andMaurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

; All Souls, New College, and St Mary's College housed respectively the arsenal, the magazine and an ordnance factory; while the mills in Osney

Osney or Osney Island (; an earlier spelling of the name is ''Oseney'') is a riverside community in the west of the city of Oxford, England. In modern times the name is applied to a community also known as Osney Town astride Botley Road, just we ...

became a powder factory. At New Inn Hall

New Inn Hall was one of the earliest medieval halls of the University of Oxford. It was located in New Inn Hall Street, Oxford.

History Trilleck's Inn

The original building on the site was Trilleck's Inn, a medieval hall or hostel for stu ...

, the requisitioned college plate was melted down into 'Oxford Crowns', and at Carfax, there was a gibbet

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, executioner's block, impalement stake, hanging gallows, or related scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of cri ...

. University life continued, although somewhat restricted and disturbed; the future kings Charles II and James II were given Master of Arts degrees, as were many others for non-academic reasons. Throughout, both sides employed poor strategies and suffered from weak intelligence, and there was less animosity between the sides than is usual in such wars.

First siege (1644)

Late in May 1644

Late in May 1644 Edmund Ludlow

Edmund Ludlow (c. 1617–1692) was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his ''Memoirs'', which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source ...

joined Sir William Waller

Sir William Waller JP (c. 159719 September 1668) was an English soldier and politician, who commanded Parliamentarian armies during the First English Civil War, before relinquishing his commission under the 1645 Self-denying Ordinance.

...

at Abingdon to blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

Oxford. According to Sir Edward Walker's diary, on 27 May Waller attempted to cross the Isis

"The Isis" () is an alternative name for the River Thames, used from its source in the Cotswolds until it is joined by the Thame at Dorchester in Oxfordshire. It derives from the ancient name for the Thames, ''Tamesis'', which in the Middle ...

at Newbridge, but was defeated by Royalist dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s. The following day, the Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

Robert Devereaux and his army forded the river at Sandford-on-Thames

Sandford-on-Thames, also referred to as simply Sandford, is a village and Parish Council beside the River Thames in Oxfordshire just south of Oxford. The village is just west of the A4074 road between Oxford and Henley.

Early history

In 108 ...

, halting on Bullingdon Green in full view of the city. Whilst the main army marched on to Islip

Islip may refer to:

Places England

* Islip, Northamptonshire

*Islip, Oxfordshire

United States

*Islip, New York, a town in Suffolk County

** Islip (hamlet), New York, located in the above town

**Central Islip, New York, a hamlet and census-d ...

to make quarters there, the Earl of Essex and a small party of horse came within cannon shot to make a closer inspection of the place. For a large part of 29 May, various parties of Parliamentarian horse troop went up and down Headington Hill

Headington Hill is a hill in the east of Oxford, England, in the suburb of Headington. The Headington Road goes up the hill leading out of the city. There are good views of the spires of Oxford from the hill, especially from the top of South Park ...

and had a few skirmishes near the ports

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

, although little damage was made on either side—the work

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physical work done by humans

** House work, housework, or homemaking

** Working animal, an animal tr ...

at St Clement's Port made three or four great shot at them, driving them back to the main body of troops. The King, being at that time on the top of Magdalen Tower

Magdalen Tower, completed in 1509, is a bell tower that forms part of Magdalen College, Oxford. It is a central focus for the celebrations in Oxford on May Morning.

History

Magdalen Tower is one of the oldest parts of Magdalen College, Oxford, ...

, had a clear view of the troops' manoeuvres.

On 30 May and 31 May the Parliamentarians made unsuccessful attempts to cross the River Cherwell

The River Cherwell ( or ) is a tributary of the River Thames in central England. It rises near Hellidon, Northamptonshire and flows southwards for to meet the Thames at Oxford in Oxfordshire.

The river gives its name to the Cherwell local g ...

at Gosford Bridge, and Earl of Cleveland

Baron Wentworth is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1529 for Thomas Wentworth, who was also ''de jure'' sixth Baron le Despencer of the 1387 creation. The title was created by writ, which means that it can descend via femal ...

Thomas Wentworth made a demonstration with 150 horse troops towards Abingdon, where Waller had 1,000 foot and 400 horse troops. Entering the town, Cleveland captured forty prisoners, but was pursued so heavily they escaped, and although he killed the commander of their party, the Royalists lost Captains de Lyne and Trist, with many more wounded.

Waller finally succeeded in forcing the passage at Newbridge on 2 June and a large contingent crossed the Isis in boats. The King went to Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. ...

to hold council and in the late evening heard news that Waller had brought some 5,000 horse and foot through Newbridge, some of which were within three miles of Woodstock. Islip and the passes over the Cherwell were abandoned, leaving matches

A match is a tool for starting a fire. Typically, matches are made of small wooden sticks or stiff paper. One end is coated with a material that can be ignited by friction generated by striking the match against a suitable surface. Wooden matc ...

burning at the bridges to deceive the Parliamentarians, the Royalists retreated to Oxford, arriving there in the early morning of 3 June. Walker notes that there was not enough supplies to last fourteen days and that if the army stayed in the city and were besieged, all would be lost in a matter of days. It was decided the King should leave Oxford that night: the King ordered a large part of the army, with cannon, to march through the city towards Abingdon to act as a diversion. The King constituted a council to govern affairs in his absence and ordered all others who were to join him to be ready at the sound of a trumpet. After a few hours the army returned from Abingdon, having successfully drawn off Waller.

On the night of 3 June 1644 at about 9 p.m. the King and Prince Charles, accompanied by various Lords and a party of 2,500 musketeers, joined the body of horse, taking the van which then marched to Wolvercote

Wolvercote is a village that is part of the City of Oxford, England. It is about northwest of the city centre, on the northern edge of Wolvercote Common, which is itself north of Port Meadow and adjoins the River Thames.

History

The Domesday B ...

and on to Yarnton

Yarnton is a village and civil parish in Oxfordshire about southwest of Kidlington and northwest of Oxford. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 2,545.

Archaeology

Early Bronze Age decorated beakers have been found in the pa ...

towards Long Hanborough

Long Hanborough is a village in Hanborough civil parish, about northeast of Witney in West Oxfordshire, England. The village is the major settlement in Hanborough parish. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 2,630.

History

An i ...

, Northleigh and Burford

Burford () is a town on the River Windrush, in the Cotswolds, Cotswold hills, in the West Oxfordshire district of Oxfordshire, England. It is often referred to as the 'gateway' to the Cotswolds. Burford is located west of Oxford and southeas ...

, which they reached at about 4 p.m. on 4 June. The army's Colours had been left standing and a further diversion was arranged by the 3,500 infantry left with the cannon in North Oxford

North Oxford is a suburban part of the city of Oxford in England. It was owned for many centuries largely by St John's College, Oxford and many of the area's Victorian houses were initially sold on leasehold by the College.

Overview

The le ...

. The Earl of Essex and his troops had crossed the River Cherwell and had some troops in Woodstock, while Waller and his forces were between Newbridge and Eynsham

Eynsham is an English village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Oxfordshire, about north-west of Oxford and east of Witney. The United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census recorded a parish population of 4,648. It was estimated at 5,0 ...

. Although without heavy baggage, the King had some sixty to seventy carriages, a large troop to have got through undiscovered. The parliamentarian scouting was seriously at fault, unaided by the lack of co-operation between Essex and Waller, it led to a disgraceful inability on the part of two large armies to counter the escape of the King. The escape being discovered, Waller made haste in pursuit, taking some few stragglers in Burford who had "regarded their drink more than their safety". The King and his forces, after assembling in the fields beyond Bourton, continued to march on to Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

. A letter from Lord Digby to Prince Rupert dated 17 June 1644, gives an indication of the immensity of the lost opportunities;

The truth of it is, had Essex and Waller jointly either pursued us or attacked Oxford, we had been lost. In the one course Oxford had been yielded up to them, having not a fortnight's provisions, and no hopes of relief. In the other Worcester had been lost, and the King forced to retreat to your Highness.Following the unproductive efforts by Essex and Waller to capture Oxford and the King, Sergeant-Major General Browne was appointed command of Parliamentarian forces on 8 June, with orders for the reduction of Oxford, Wallingford,

Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshire ...

, and the Fort of Greenland House. Browne was also to select and preside over a council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

of twelve men, and although he greatly troubled Oxford from then on, there were no further attempts on the city during the 1644 campaign season.

Second siege (1645)

In the New Year, one of the first objectives of theNew Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

was the blockade and siege of Oxford, initially intending that Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

and Browne go to Oxford, while Fairfax marched to the west. Fairfax was in Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of Letter (alphabet), letters, symbols, etc., especially by Visual perception, sight or Somatosensory system, touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process invo ...

on 30 April 1645 and by 4 May had reached Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

* Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Ando ...

, where he received orders to prevent Prince Rupert getting to Oxford. On 6 May Fairfax was ordered to join Cromwell and Browne at Oxford and to send 3,000 foot soldiers and 1,500 horse soldiers to relieve Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

, which he accomplished on 12 May. The committee had ordered a voluntary contribution from Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Berkshire to raise forces to take Oxford and on 17 May planned for funding Fairfax in the reducing of Oxford, so that "it may prevent all Provisions and Ammunition to be brought in". On 19 May Fairfax arrived in Cowley and made his way over Bullingdon Green and on to Marston, showing himself on Headington Hill. On the 22 May he began the siege by raising a breastwork on the east side of the River Cherwell and erecting a bridge at Marston. On 23 May the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

gave the Committee of the Army orders to "make Provision for such Money and Necessaries for the Siege of ''Oxon'', as they have or shall Receive directions for from the Committee of Both Kingdoms

The Committee of Both Kingdoms, (known as the Derby House Committee from late 1647), was a committee set up during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by the Parliamentarian faction in association with representatives from the Scottish Covenanters, aft ...

, not exceeding the Sum of Six thousand Pounds", having already agreed that £10,000 was to await Fairfax at Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

, along with the following provision for a siege:

According to Sir William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Coleshi ...

's diary, on 23 May Fairfax was at Marston and his troops began crossing the river, the outhouses of Godstow House were fired, causing the occupants to evacuate to Oxford, and the house occupied by the Parliamentarians. On 26 May Fairfax put four regiments of foot soldiers with thirteen carriages by the newly erected bridge at Marston, the King's forces 'drowned' the meadow, fired houses in the suburbs and placed a garrison at Wolvercote. Whilst viewing the ongoing works, Fairfax had a narrow escape from being shot. On the following day two of Fairfax's regiments—the white and the red—with two pieces of ordnance marched to Godstow House and on to Hinksey

Hinksey is a place name associated with Oxford and Oxfordshire. In 1974, many of the places associated with the name were transferred from the county of Berkshire in the county boundary changes.

History

The place-name is of Old English origin. ...

. The Auxiliaries on duty in Oxford; the Lord Keeper

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of ...

, the Lord Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State i ...

, and the Mayor of Oxford marched before their Companies to the Guards. In the evening of 29 May a "bullet of ix lb. weight, shot from the Rebels warning piece at Marston, fell against the wall on the north side of the Hall in Christ Church". Meanwhile Gaunt House near Newbridge was under siege by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Thomas Rainsborough

Thomas Rainsborough, or Rainborowe, 6 July 1610 – 29 October 1648, was an English religious and political radical who served in the Parliamentarian navy and New Model Army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. One of the few contemporaries wh ...

with 600 foot soldiers and 200 horse. Next day the sound of firing at Gaunt House could be heard in Oxford and the following day Rainsborough took the house and 50 prisoners.

In the early hours of the morning on 2 June the troops in Oxford made a sally

Sally may refer to:

People

*Sally (name), a list of notable people with the name

Military

*Sortie (siege warfare), Sally (military), an attack by the defenders of a town or fortress under siege against a besieging force; see sally port

*Sally, ...

and a party of foot and horse attacked the Parliamentarian Guard at Headington Hill, killing 50 and taking 96 prisoners, many seriously wounded. In the afternoon Parliamentarian forces drove off 50 cattle grazing in fields outside the East Gate. On 3 June the prisoners taken the day before were exchanged and the following day the siege was raised and the bridge over the River Cherwell was demolished. The Parliamentarian forces withdrew the troops from Botley and Hinksey, and also withdrew from their headquarters at Marston and on 5 June they completed evacuating Marston and Wolvercote. The reason for such a sudden withdrawal was that the King, Prince Rupert, Prince Maurice, and the Earl of Lindsey

Earl of Lindsey is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1626 for the 14th Baron Willoughby de Eresby (see Baron Willoughby de Eresby for earlier history of the family). He was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1635 to 1636 a ...

, Montagu Bertie and others had left Oxford on 7 May. In the meantime, Fairfax, who disliked spending time in siege warfare, had prevailed upon the committee to allow him to lift the siege and follow the King. A letter by Fairfax to his father dated 4 June 1645 explains:

I am very sorry we should spend our time unprofitably before a town, whilst the King hath time to strengthen himself, and by terror to force obedience of all places where he comes; the Parliament is sensible of this now, therefore hath sent me directions to raise the siege and march to Buckingham, where, I believe, I shall have orders to advance northwards, in such a course as all our divided parties may join. It is the earnest desire of this Army to follow the King, but the endeavours of others prevent it hath so much prevailed.On 5 June, Fairfax abandoned the siege, having received orders to engage the King and recapture

Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

instead.

Third siege (1646)

The King returned to Oxford on 5 November 1645 to quarter for the winter. The Royalists planned to resume the campaign in the spring and sent Lord Astley to Worcester to collect a force fromWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. However, on the journey back his troops were routed at Stow-on-the-Wold

Stow-on-the-Wold is a market town and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England, on top of an 800-foot (244 m) hill at the junction of main roads through the Cotswolds, including the Fosse Way (A429), which is of Roman origin. The town was found ...

by Parliamentarian forces under the command of Sir William Brereton, and Astley and his officers were taken prisoner. Two letters from the King to the Queen are of note; the first, dated 6 April 1646 advised her that he was expecting to be received into the Scots army, the second letter of his is dated 22 April stated: "I resolved from hence to venture breaking thro' the rebells' quarters (which, upon my word, was neither a safe nor an easy work) to meet them where they should appoint; and I was so eager upon it, that, had it not been for Pr. Rupert's backwardness, I had tryed it without hearing from them, being impatient of delay" and that the King intended to travel in disguise to Lynn and on to Montrose by sea.

The committee in London again ordered its forces to 'straiten' Oxford. On 18 March there was a skirmish between the Oxford Horse and troops commanded by Colonel Charles Fleetwood

Charles Fleetwood (c. 1618 – 4 October 1692) was an English Parliamentarian soldier and politician, Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1652–1655, where he enforced the Cromwellian Settlement. Named Cromwell's Lieutenant General for the Third Englis ...

, and 2,000 Parliamentarians under the command of Rainsborough came into Woodstock from Witney

Witney is a market town on the River Windrush in West Oxfordshire in the county of Oxfordshire, England. It is west of Oxford. The place-name "Witney" is derived from the Old English for "Witta's island". The earliest known record of it is as ...

. On 30 March Rainsborough's foot soldiers and all four of Fairfax's horse regiments were ordered to "such places as will wholly block up Oxford" and make the inhabitants "presently to live at the expense of their Stores". On 3 April Browne, the Governor of Abingdon, was ordered to send fifty barrels of gunpowder to Rainsborough.

On 4 April Colonel Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton ((baptised) 3 November 1611 – 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 16 ...

was given orders by Fairfax to join those forces assembling for the 'straitening' of Oxford. On 10 April the House of Commons referred to the committee to "take some course for the stricter Blocking up of ''Oxon'', and guarding the Passes between ''Oxon'' and the Cities of ''London'' and ''Westminster''", the committee was directed to draw up a general summons to ask the King's garrisons to surrender under a penalty for refusal. On 15 April the sound of cannon firing against Woodstock Manor House could be heard in Oxford, and at about 6 p.m. Rainsborough's troops attacked but were beaten back, losing 100 men, their scaling ladders were taken and many others wounded. On 26 April the Manor House was surrendered, its Governor and his soldiers, without their weapons, returned to Oxford in the evening. The King left the city early in the morning of 27 April without disclosing his destination to those privy to his departure; There are two letters from Colonel Payne, commander of the garrison in Abingdon, to Browne—one dated 27 April reporting intelligence that the King went in disguise to London, making use of Fairfax's seal that had been duplicated by them in Oxford; the other is dated 29 April noting the common reports of the King's flight:

On 30 April the House of Commons, having heard of the King's flight the previous day, issued orders that no person was to be allowed "out of Oxford, by pass or otherwise, except it be upon parley or treaty, concerning the surrendering of the garrison, of some fort, or otherwise advantageous, for reducing of the garrison". On 1 May, Fairfax returned to Oxford to place the city under siege, as had been expected. On 2 May Parliamentarian soldiers entered the villages around Oxford, such as Headington and Marston, following a general rendezvous of the army at Bullingdon Green. On 3 May the Parliamentarians held a council of war where it was decided that a "Quarter" on Headington Hill should be made to hold 3,000 men, it was also decided to build a bridge over the River Cherwell at Marston. The General's regiment and that of Colonel Pickering were to be stationed at Headington, the Major General's and Colonel Harley's at Marston, Colonel Thomas Herbert's, and Colonel Sir Hardress Waller

Sir Hardress Waller (1666), was an English Protestant who settled in Ireland and fought for Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A leading member of the radical element within the New Model Army, he signed the death warrant for the Ex ...

's Regiments at Cowley, whilst the train of artillery was placed at Elsfield

Elsfield is an English village and civil parish about northeast of the centre of Oxford. The village is above sea level on the western brow of a hill with relatively steep sides above the River Cherwell. For relative reference purposes, the O ...

, a fourth quarter was made on the north side of Oxford, where most of the foot troops were assembled to enable approaches across ground near to the city walls. Meanwhile, the towns of Faringdon

Faringdon is a historic market town in the Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire, England, south-west of Oxford, north-west of Wantage and east-north-east of Swindon. It extends to the River Thames in the north; the highest ground is on the Rid ...

, Radcot

Radcot Bridge is a crossing of the Thames in England, south of Radcot, Oxfordshire, and north of Faringdon, Oxfordshire which is in the district of that county that was in Berkshire. It carries the A4095 road across the reach above Radcot Loc ...

, Wallingford and Boarstall House were completely blockaded. Within cannon shot from the city, Fairfax's men began to construct a line from the 'Great Fort' on Headington Hill towards St Clement's, lying outside Magdalen Bridge

Magdalen Bridge spans the divided stream of the River Cherwell just to the east of the City of Oxford, England, and next to Magdalen College, whence it gets its name and pronunciation. It connects the High Street to the west with The Plain, no ...

. On 6 May the magazine for provisions in Oxford was opened and from then on 4,700 were fed from it, "being more by 1,500, as 'twas thought, than upon a true muster the soldiers were".

On 11 May Fairfax sent in a demand of surrender to the Governor:

That afternoon, Prince Rupert was wounded for the first time, being shot in the upper arm whilst on a raiding party in the fields to the North of Oxford. On 13 May the first shot was fired from the 'Great Fort' on Headington Hill, the shot falling in Christ Church Meadow. The Governor, Sir Thomas Glemham, and the officers of the garrison of Oxford gave the opinion to the Lords of the Privy Council that the city was defensible.

On 14 May the Governor of Oxford, under direction from the Privy Council, sent a letter to Fairfax offering to treat on the Monday (18 May), asking for their commissioners to meet. Fairfax, in council of war, sent a reply the same day, agreeing to the time and naming Mr Unton Croke

Unton Croke (159328 January 1671) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons in 1628 and 1640. He supported the Roundheads, Parliamentarian cause during the English Civil War.

Croke was the so ...

's house at Marston as the meeting place. The Privy Council ordered that all their books and papers of parliamentary proceedings transacted in Oxford were to be burned. On 16 May the Governor gave the Privy Council a paper requiring that the Lords "justify under their hands that they have regal power in the King's absence; namely, to deliver up Garrisons, levy forces and the like. Whereupon the Lords signed a paper whereby they challenged the like power". On 17 May the Governor and all his principal officers of the garrison signed a paper "manifesting their dislike in opinion of the present Treaty", and alleged it was forced upon them by the Lords of Council:

This disclaimer of responsibility did little to delay the progress of the Treaty, the civilians, with a better sense of the situation, thought that delay "might be of ill consequence". The same day the Governor sent his acceptance and names of his commissioners to Fairfax; Sir John Monson, Sir John Heydon

Sir John Heydon (died 1653) was an English Royalist military commander and mathematician, Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance at the outbreak of the First English Civil War.

Life

The second son of Sir Christopher Heydon, in 1613 he was keeper of ...

, Sir Thomas Gardiner, Sir George Binyon, Sir Richard Willis, Sir Stephen Hawkyns, Colonels Robert Gosnold and Henry Tillier, Richard Zouch

Richard Zouch (1 March 1661) was an English judge and a member of parliament from 1621 to 1624. He was elected Member of Parliament for Hythe in 1621 and later became principal of St. Alban Hall, Oxford. During the Civil War he was a Royalist an ...

, Thomas Chicheley

Sir Thomas Chicheley (25 March 1614 – 1 February 1699) of Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire was a politician in England in the seventeenth century who fell from favour in the reign of James II. His name is sometimes spelt as Chichele.

Life

He was ...

, John Dutton, Geoffrey Palmer Geoffrey Palmer may refer to:

Politicians

* Sir Geoffrey Palmer, 1st Baronet (1598–1670), English lawyer and politician

*Sir Geoffrey Palmer, 3rd Baronet (1655–1732), English politician, Member of Parliament (MP) for Leicestershire

*Geoffrey Pa ...

, Philip Warwick

Sir Philip Warwick (24 December 160915 January 1683), English writer and politician, born in Westminster, was the son of Thomas Warwick, or Warrick, a musician.

Life

He was educated at Eton, he travelled abroad for some time and in 1636 became ...

, and Captain Robert Mead. Fairfax, in return sent the names of his commissioners; Thomas Hammond, Henry Ireton, Colonels John Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

*John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

* John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c. ...

, Charles Rich and Robert Harley, Leonard Watson, Majors John Desborough

John DesboroughAlso spelt John Disbrowe and John Desborow (the latter in the Indemnity and Oblivion Act, section XLIII) (1608–1680) was an English soldier and politician who supported the parliamentary cause during the English Civil War.

...

and Thomas Harrison, Thomas Herbert and Hardress Waller; later, the names of Henry Boulstred, John Mills and Matthew Hale were added.

Treaty

Some discussion followed about it being usual at all treaties to appoint secretaries, to which Fairfax agreed; the Oxford commissioners were to bring Henry Davidson as their secretary, the Parliamentarians would bring William Clark. The first session took place at Croke's house on 18 May, as originally agreed. A letter from N.T. (whose identity is unknown) in Marston on 20 May complains about the 'lumbering at Oxford' and the procrastination of the Oxford commissioners; the letter concludes: A first draft of the articles was referred by Fairfax to the House of Commons, presented by Colonel Rich on 22 May. The Journals of the House record that the House did "upon the very first view of them, disdain those Articles and overtures offered by those at ''Oxon''" and left Fairfax to "proceed effectually, according to the trust reposed in him, for the speedy gaining and reducing the garrison of ''Oxon'' to the obedience of the Parliament". On 23 May the commissioners returned to Marston and according to Dugdale's diary "the adverse party pretended our Articles to be too high, said they would offer Articles, and so the Treaty broke off at the time". On 25 May a Committee of nine Lords and nine of the Commons was constituted to consider honourable conditions for Oxford's surrender. A conference of both Houses met upon a letter from the King, written from Newcastle, dated 18 May, enclosing a letter for Glemham, the debate continued into the following day. The King's letter regarding Oxford stated: On 15 June the heads of conference with the Commons viewed the King's letter of 18 May and another from the King, dated 10 June, which was similar in terms, but included an order from the King "directed to the Governors of Oxford, Lichfield, Worcester, Wallingford, and all other Commanders of any his Towns, Castles, and Forts within England and Wales". The heads of conference wanted the warrant sent to Fairfax and for him to forward it on. In the Commons it was ordered that the warrant of 10 June be sent to all Governors "for Preventing of the further Effusion of Christian Blood". Dugdale's diary for 30 May records: "This evening Sir Tho. Fairfax sent in a Trumpet to Oxford, with Articles concerning the delivery thereof". Rushworth, who was Fairfax's secretary at the time stated that Fairfax drew up the Articles; however, the Committee of the two Houses appointed on 25 May may have had a hand in them. The Treaty was renewed, the Oxford commissioners taking the stance that they submitted themselves "to the Fate of the Kingdom, rather than any way distrusting their own Strength, or the Garrison's Tenableness". The resumption of the Treaty coincided with a seemingly random exchange of cannon fire, Oxford loosing 200 shot in the day, managing to land a great shot in the Leaguer on Headington Hill, killing Colonel Cotsworth. A sutler and others were killed in Rainsborough's camp, while the Parliamentarian "cannon in recompense played fiercely upon the defendants, and much annoyed them in their works, houses, and colleges, till at last a cessation of great shot was agreed to on both sides". On 1 June Fairfax was prepared to take the city by storm if necessary. On 3 June Oxford forces made a sally from East Port, and about 100 cavalry troopers attempted drive in some cattle grazing near Cowley, but the Parliamentarian horse countered them in skirmishes, during which Captain Richardson and two more were killed. On 4 June the commissioners met again in Marston to consider the new articles offered by Fairfax. On 8 June various Oxford gentlemen delivered a paper of particulars to the Privy Council, which they wanted to add into the Treaty, asking to be informed of the proceedings and to be allowed attendance with the commissioners. On 9 June the commissioners were sworn to secrecy over the talks and forbidden to say anything about their proceedings. On 10 June Fairfax sent a present of "a brace of Bucks, 2 Muttons, 2 Veals, 2 Lambs, 6 Capons, and Butter" into Oxford for theDuke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

(James II). A letter from Fairfax to his father, dated 13 June, states:

On 17 June there was a general cessation of arms and extensive fraternizing between the two armies. The Privy Council did not dare meet in the Audit House as was usual "in regard of the mutinous soldiers, especially reformadoes". The following day the clergy with others reproached the Lords of the Privy Council for the terms of the Treaty; the next day, the Lords of the Privy Council walked with swords on, fearing for their own safety. On 20 June the Articles of Surrender, including provisions for academics and citizens, were agreed upon at Water Eaton, and signed in the Audit House of Christ Church; for the first side by the Privy Council and the Governor of Oxford, and Fairfax for the other.

On 21 June the Lords of the Privy Council held a meeting with the gentlemen of the town in the Audit House, at which the Lord Keeper made a speech about the need to conclude the Treaty, and read them the authority of the two letters from the King. A copy of the '' Moderate Intelligencer'' was produced, along with an account of the Scots "pressing the King's conscience so far that sundry times he was observed to retire and weep", which affected the Lord Keeper similarly. On 22 June Princes Rupert and Maurice were given permission by Fairfax to leave Oxford and go to Oatlands, to see the Elector, despite it being contrary to the terms of the Articles. The matter was debated in the House of Commons on 26 June, the Princes were commanded "to repair to the Sea Side, within Ten Days; and forwith to depart the Kingdom". Prince Rupert sent a long letter, from himself and Maurice, arguing that they did not violate the terms of the Treaty, but offered to submit if his argument failed.

On 24 June, the day set for the Treaty to come into operation, the evacuation of Oxford by the Royalists began. It was not possible to withdraw the entire garrison in one day, but under Article 5 a large body of the regular garrison, some 2,000 to 3,000 men, marched out of the city with all the honours of war. Those living in North Oxford went by the North Port, and some 900 marched out over Magdalen Bridge, on to Headington Hill

Headington Hill is a hill in the east of Oxford, England, in the suburb of Headington. The Headington Road goes up the hill leading out of the city. There are good views of the spires of Oxford from the hill, especially from the top of South Park ...

between the lines of the Parliamentarian troops, and on to Thame

Thame is a market town and civil parish in Oxfordshire, about east of the city of Oxford and southwest of Aylesbury. It derives its name from the River Thame which flows along the north side of the town and forms part of the county border wi ...

where they were disarmed and dispersed with their passes. The form of pass issued by Fairfax was:

Although 2,000 passes were issued over a few days, a number of people had to wait their turn. On 25 June the keys of the city were formally handed over to Fairfax; with the larger part of the regular Oxford garrison having left the day before, he sent in three regiments of foot soldiers to maintain order. The evacuation subsequently continued in an orderly fashion, and peace returned to Oxford.

See also

*Siege of Reading

The siege of Reading was an eleven-day blockade of Reading, Berkshire, during the First English Civil War. Reading had been garrisoned by the Royalists in November 1642, and held 3,300 soldiers under the command of Sir Arthur Aston. On 1 ...

Notes

Citations

References

* otherwise known as ''Fairfax Correspondence Volume 3'' * * * * Contemporary diary with a near day by day account of the third siege. * * Review of the 1932 book by Varley. * * * * * * Contemporary diary with an account of the first siege. * * * * . 1803 reprint * . 1803 reprint * . 1803 reprint * . 1767-1830 reprintFurther reading

* * *External links

Oxford Crown

Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of ...

: British Archaeology Collections.

''Siege of Oxford'' (1646)

painting by Jan de Wyck.

Reproduction of a 1644 map of the defences of Oxford

by

English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oxford, Siege of

Sieges of the English Civil Wars

History of Oxford

Military history of Oxfordshire

1644 in England

1645 in England

1646 in England

Conflicts in 1644

Conflicts in 1645

Conflicts in 1646

First English Civil War

17th century in Oxfordshire