Siege Of Nirayama on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A siege is a

A siege is a  Ancient cities in the Middle East show

Ancient cities in the Middle East show

Although there are depictions of sieges from the ancient Near East in historical sources and in art, there are very few examples of siege systems that have been found archaeologically. Of the few examples, several are noteworthy:

* The late 9th-century BC siege system surrounding

Although there are depictions of sieges from the ancient Near East in historical sources and in art, there are very few examples of siege systems that have been found archaeologically. Of the few examples, several are noteworthy:

* The late 9th-century BC siege system surrounding

An attacker's first act in a siege might be a surprise attack, attempting to overwhelm the defenders before they were ready or were even aware there was a threat. This was how William de Forz captured

An attacker's first act in a siege might be a surprise attack, attempting to overwhelm the defenders before they were ready or were even aware there was a threat. This was how William de Forz captured  To end a siege more rapidly, various methods were developed in ancient and medieval times to counter fortifications, and a large variety of

To end a siege more rapidly, various methods were developed in ancient and medieval times to counter fortifications, and a large variety of

When enemies attempted to dig tunnels under walls for mining or entry into the city, the defenders used large

When enemies attempted to dig tunnels under walls for mining or entry into the city, the defenders used large

The importance of siege warfare in the ancient period should not be underestimated. One of the contributing causes of

The importance of siege warfare in the ancient period should not be underestimated. One of the contributing causes of

online

Other examples include the

However, the Chinese were not completely defenseless, and from AD 1234 until 1279, the Southern Song Chinese held out against the enormous barrage of Mongol attacks. Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (i.e. with early

However, the Chinese were not completely defenseless, and from AD 1234 until 1279, the Southern Song Chinese held out against the enormous barrage of Mongol attacks. Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (i.e. with early

However, new fortifications, designed to withstand gunpowder weapons, were soon constructed throughout Europe. During the

However, new fortifications, designed to withstand gunpowder weapons, were soon constructed throughout Europe. During the

The most effective way to protect walls against cannonfire proved to be depth (increasing the width of the defences) and angles (ensuring that attackers could only fire on walls at an oblique angle, not square on). Initially, walls were lowered and backed, in front and behind, with earth. Towers were reformed into triangular bastions. This design matured into the ''

The most effective way to protect walls against cannonfire proved to be depth (increasing the width of the defences) and angles (ensuring that attackers could only fire on walls at an oblique angle, not square on). Initially, walls were lowered and backed, in front and behind, with earth. Towers were reformed into triangular bastions. This design matured into the ''

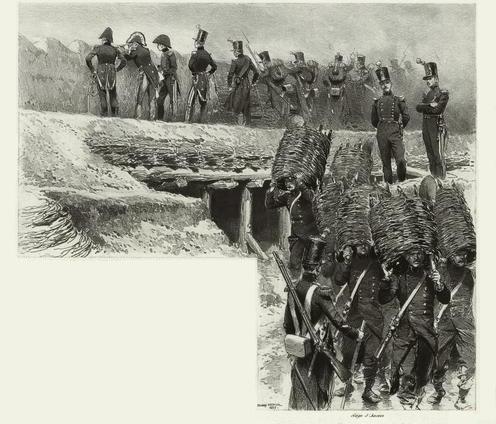

At the end of the 17th century, two influential military engineers, the French

At the end of the 17th century, two influential military engineers, the French  Another element of a fortress was the

Another element of a fortress was the

The exception to this rule were the English. During the

The exception to this rule were the English. During the  Experienced commanders on both sides in the English Civil War recommended the abandonment of garrisoned fortifications for two primary reasons. The first, as for example proposed by the Royalist Sir Richard Willis to King Charles, was that by abandoning the garrisoning of all but the most strategic locations in one's own territory, far more troops would be available for the field armies, and it was the field armies which would decide the conflict. The other argument was that by slighting potential strong points in one's own territory, an enemy expeditionary force, or local enemy rising, would find it more difficult to consolidate territorial gains against an inevitable counterattack. Sir

Experienced commanders on both sides in the English Civil War recommended the abandonment of garrisoned fortifications for two primary reasons. The first, as for example proposed by the Royalist Sir Richard Willis to King Charles, was that by abandoning the garrisoning of all but the most strategic locations in one's own territory, far more troops would be available for the field armies, and it was the field armies which would decide the conflict. The other argument was that by slighting potential strong points in one's own territory, an enemy expeditionary force, or local enemy rising, would find it more difficult to consolidate territorial gains against an inevitable counterattack. Sir

Advances in artillery made previously impregnable defences useless. For example, the walls of

Advances in artillery made previously impregnable defences useless. For example, the walls of

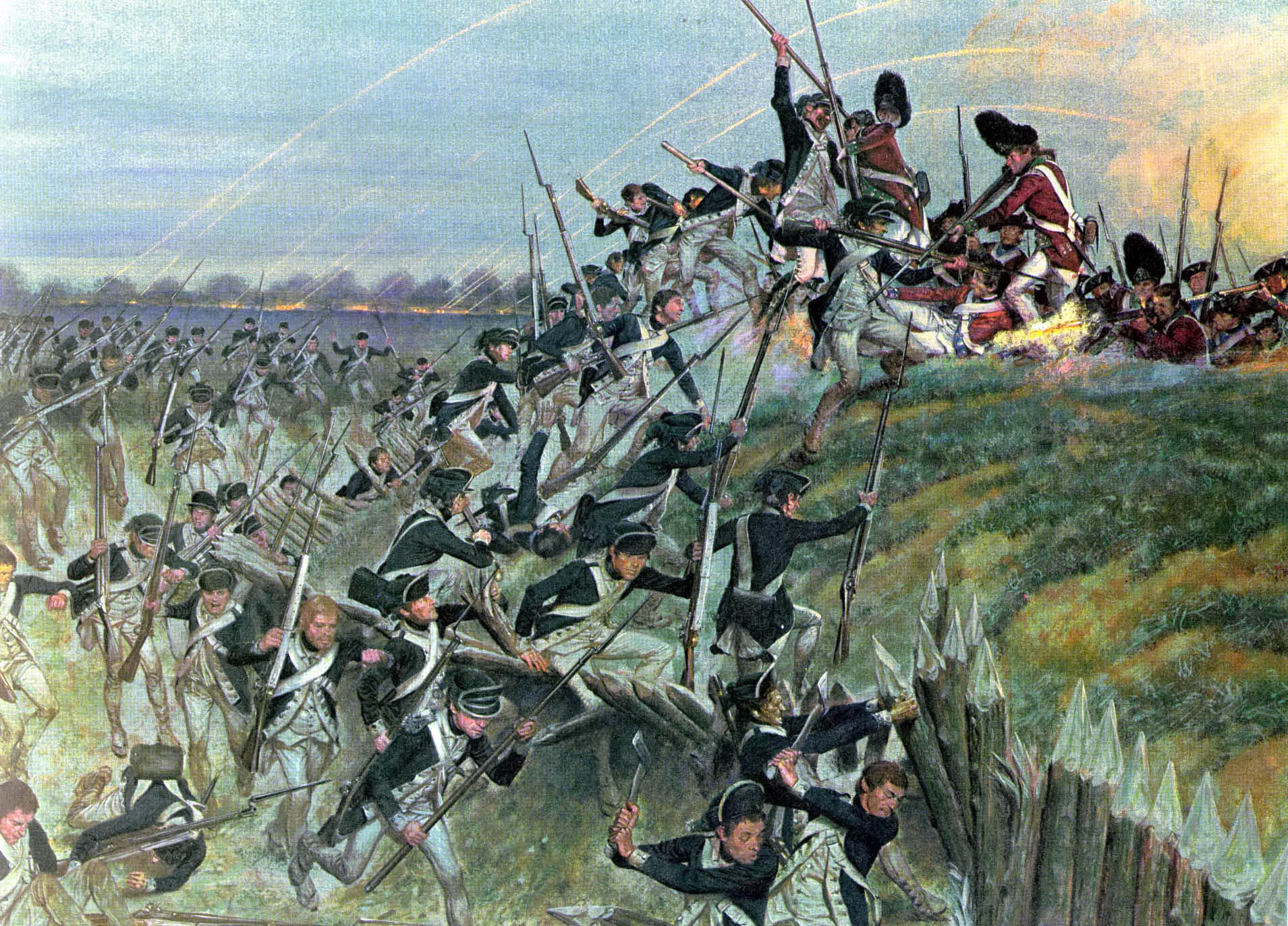

Mainly as a result of the increasing firepower (such as

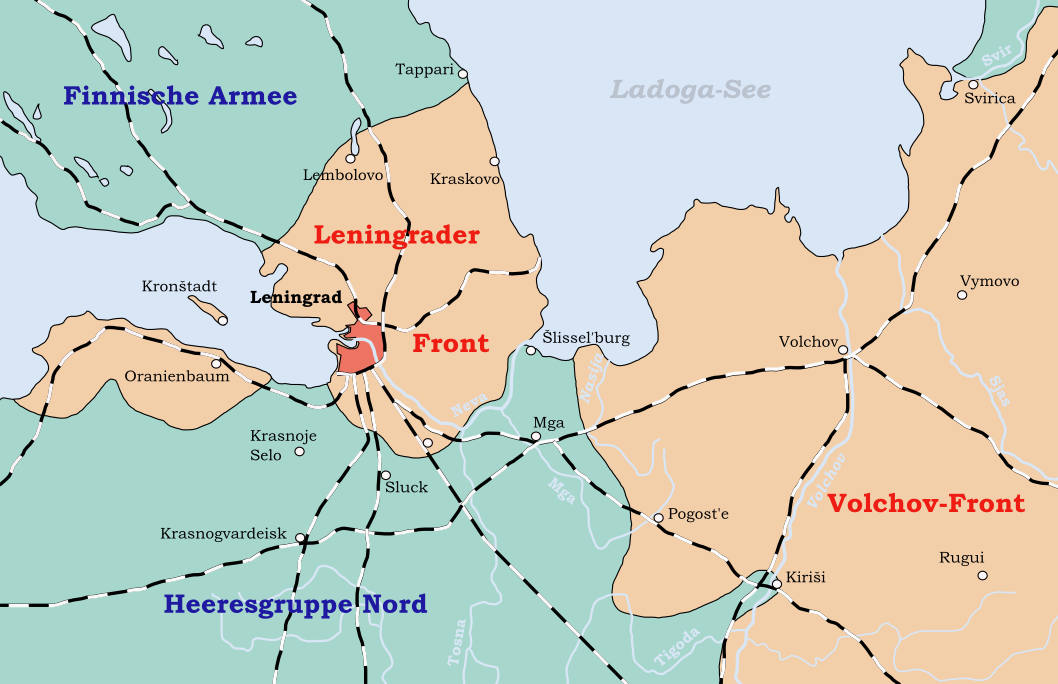

Mainly as a result of the increasing firepower (such as  The largest sieges of the war, however, took place in Europe. The initial German advance into Belgium produced four major sieges: the

The largest sieges of the war, however, took place in Europe. The initial German advance into Belgium produced four major sieges: the  At the second

At the second

The most important siege was the

The most important siege was the

Several times during the

Several times during the

Siege tactics continue to be employed in police conflicts. This has been due to a number of factors, primarily risk to life, whether that of the

Siege tactics continue to be employed in police conflicts. This has been due to a number of factors, primarily risk to life, whether that of the

Native American Siege Warfare.

Biblical perspectives.

Secrets of Lost Empires: Medieval Siege

(PBS) Informative and interactive webpages about medieval siege tactics. {{Authority control Military strategy * Warfare of the Middle Ages

A siege is a

A siege is a military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

of a city, or fortress

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, with the intent of conquering by attrition

Attrition may refer to

*Attrition warfare, the military strategy of wearing down the enemy by continual losses in personnel and material

**War of Attrition, fought between Egypt and Israel from 1968 to 1970

**War of attrition (game), a model of agg ...

, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static, defensive position. Consequently, an opportunity for negotiation

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach the desired outcome regarding one or more issues of conflict. It is an interaction between entities who aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement c ...

between combatants is common, as proximity and fluctuating advantage can encourage diplomacy. The art of conducting and resisting sieges is called siege warfare, siegecraft, or poliorcetics.

A siege occurs when an attacker encounters a city or fortress that cannot be easily taken by a quick assault, and which refuses to surrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

. Sieges involve surrounding the target to block the provision of supplies and the reinforcement or escape of troops (a tactic known as "investment

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing i ...

"). This is typically coupled with attempts to reduce the fortifications by means of siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while other ...

s, artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

bombardment, mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

(also known as sapping), or the use of deception or treachery to bypass defenses.

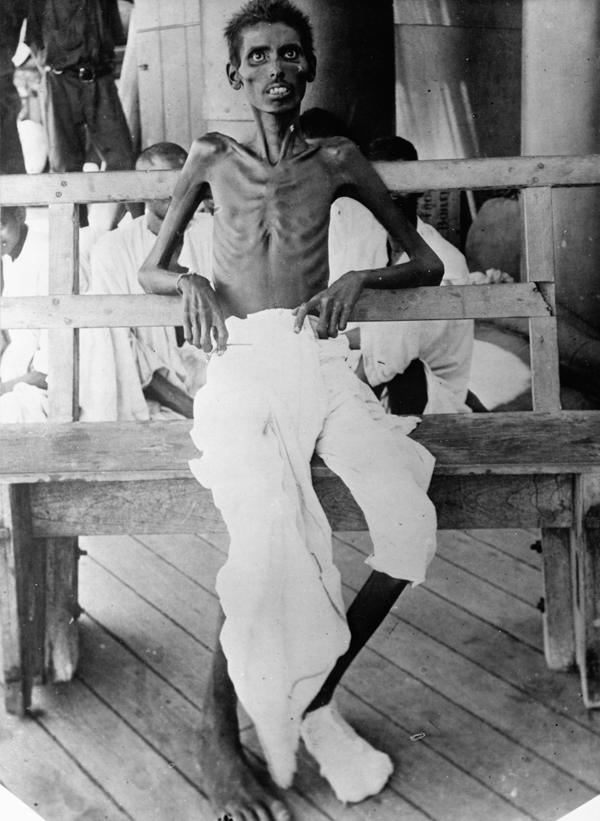

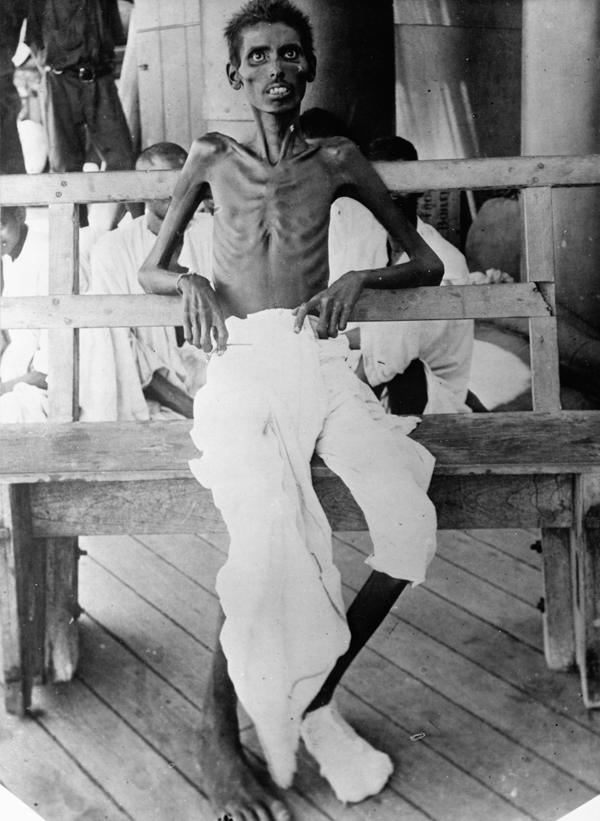

Failing a military outcome, sieges can often be decided by starvation, thirst, or disease, which can afflict either the attacker or defender. This form of siege, though, can take many months or even years, depending upon the size of the stores of food the fortified position holds.

The attacking force can circumvallate the besieged place, which is to build a line of earth-works, consisting of a rampart and trench, surrounding it. During the process of circumvallation, the attacking force can be set upon by another force, an ally of the besieged place, due to the lengthy amount of time required to force it to capitulate. A defensive ring of forts outside the ring of circumvallated forts, called contravallation, is also sometimes used to defend the attackers from outside.

Ancient cities in the Middle East show

Ancient cities in the Middle East show archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

evidence of fortified city wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

s. During the Warring States era

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conques ...

of ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

, there is both textual and archaeological evidence of prolonged sieges and siege machinery used against the defenders of city walls. Siege machinery was also a tradition of the ancient Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

. During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

and the early modern period, siege warfare dominated the conduct of war in Europe. Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

gained as much of his renown from the design of fortifications as from his artwork.

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

campaigns were generally designed around a succession of sieges. In the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislative ...

, increasing use of ever more powerful cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s reduced the value of fortifications. In the 20th century, the significance of the classical siege declined. With the advent of mobile warfare

Mobile warfare () is a military strategy of the People’s Republic of China employing conventional forces on fluid fronts with units maneuvering to exploit opportunities for tactical surprise, or where a local superiority of forces can be real ...

, a single fortified stronghold is no longer as decisive as it once was. While traditional sieges do still occur, they are not as common as they once were due to changes in modes of battle, principally the ease by which huge volumes of destructive power can be directed onto a static target. Modern sieges are more commonly the result of smaller hostage, militant, or extreme resisting arrest

Resisting arrest, or simply resisting, is an illegal act of a suspected criminal either fleeing, threatening, assaulting, or providing a fake ID to a police officer during arrest. In most cases, the person responsible for resisting arrest is crimi ...

situations.

Ancient period

The necessity of city walls

TheAssyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

ns deployed large labour forces to build new palaces, temples, and defensive walls. Some settlements in the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

were also fortified. By about 3500 BC, hundreds of small farming villages dotted the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

floodplain. Many of these settlements had fortifications and planned streets.

The stone and mud brick houses of Kot Diji

The ancient site at Kot Diji ( sd, ڪوٽ ڏیجي; ur, کوٹ ڈیجی) was the forerunner of the Indus Civilization. The occupation of this site is attested already at 3300 BCE. The remains consist of two parts; the citadel area on high ground ...

were clustered behind massive stone flood dikes and defensive walls, for neighbouring communities quarrelled constantly about the control of prime agricultural land. Mundigak

Mundigak ( ps, منډیګک) is an archaeological site in Kandahar province in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at ...

(c. 2500 BC) in present-day south-east Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

has defensive walls and square bastions of sun-dried bricks.

City walls and fortifications were essential for the defence of the first cities in the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

. The walls were built of mudbricks, stone, wood, or a combination of these materials, depending on local availability. They may also have served the dual purpose of showing potential enemies the might of the kingdom. The great walls surrounding the Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

ian city of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Harm ...

gained a widespread reputation. The walls were in length, and up to in height.

Later, the walls of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, reinforced by towers, moats, and ditches, gained a similar reputation. In Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-centra ...

built massive stone walls around their cities atop hillsides, taking advantage of the terrain. In Shang Dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and ...

China, at the site of Ao, large walls were erected in the 15th century BC that had dimensions of in width at the base and enclosed an area of some squared.Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 43. The ancient Chinese capital for the State of Zhao

Zhao () was one of the seven major State (Ancient China), states during the Warring States period of ancient China. It was created from the three-way Partition of Jin, together with Han (state), Han and Wei (state), Wei, in the 5th century BC. ...

, Handan

Handan is a prefecture-level city located in the southwest of Hebei province, China. The southernmost prefecture-level city of the province, it borders Xingtai on the north, and the provinces of Shanxi on the west, Henan on the south and Shando ...

, founded in 386 BC, also had walls that were wide at the base; they were tall, with two separate sides of its rectangular enclosure at a length of 1,530 yd (1,400 m).

The cities of the Indus Valley Civilization showed less effort in constructing defences, as did the Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450BC ...

on Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. These civilizations probably relied more on the defence of their outer borders or sea shores. Unlike the ancient Minoan civilization, the Mycenaean Greeks

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

emphasized the need for fortifications alongside natural defences of mountainous terrain, such as the massive Cyclopean walls

Cyclopean masonry is a type of stonework found in Mycenaean architecture, built with massive limestone boulders, roughly fitted together with minimal clearance between adjacent stones and with clay mortar or no use of mortar. The boulders typic ...

built at Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. Th ...

and other adjacent Late Bronze Age (c. 1600–1100 BC) centers of central and southern Greece.

Archaeological evidence

Although there are depictions of sieges from the ancient Near East in historical sources and in art, there are very few examples of siege systems that have been found archaeologically. Of the few examples, several are noteworthy:

* The late 9th-century BC siege system surrounding

Although there are depictions of sieges from the ancient Near East in historical sources and in art, there are very few examples of siege systems that have been found archaeologically. Of the few examples, several are noteworthy:

* The late 9th-century BC siege system surrounding Tell es-Safi

Tell es-Safi ( ar, تل الصافي, Tall aṣ-Ṣāfī, "White hill"; he, תל צפית, ''Tel Tzafit'') was an Arab Palestinian village, located on the southern banks of Wadi 'Ajjur, northwest of Hebron which had its Arab population expelled ...

/ Gath, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, consists of a 2.5 km long siege trench, towers, and other elements, and is the earliest evidence of a circumvallation

Investment is the military process of surrounding an enemy fort (or town) with armed forces to prevent entry or escape. It serves both to cut communications with the outside world and to prevent supplies and reinforcements from being introduced ...

system known in the world. It was apparently built by Hazael

Hazael (; he, חֲזָאֵל, translit=Ḥazaʾēl, or , romanized as: ; oar, 𐡇𐡆𐡀𐡋, translit= , from the triliteral Semitic root ''h-z-y'', "to see"; his full name meaning, " El/God has seen"; akk, 𒄩𒍝𒀪𒀭, Ḫa-za-’- il ...

of Aram Damascus

The Kingdom of Aram-Damascus () was an Aramean polity that existed from the late-12th century BCE until 732 BCE, and was centred around the city of Damascus in the Southern Levant. Alongside various tribal lands, it was bounded in its later ye ...

, as part of his siege and conquest of Philistine

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

Gath in the late 9th century BC (mentioned in II Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the books ...

12:18).

* The late 8th-century BC siege system surrounding the site of Lachish

Lachish ( he, לכיש; grc, Λαχίς; la, Lachis) was an ancient Canaanite and Israelite city in the Shephelah ("lowlands of Judea") region of Israel, on the South bank of the Lakhish River, mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. Th ...

(Tell el-Duweir) in Israel, built by Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

of Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

in 701 BC, is not only evident in the archaeological remains, but is described in Assyrian and biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

sources and in the reliefs of Sennacherib's palace in Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

.

* The siege of Alt-Paphos

Paphos ( el, Πάφος ; tr, Baf) is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and New Paphos.

The current city of Pap ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

by the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

army in the 4th century BC.

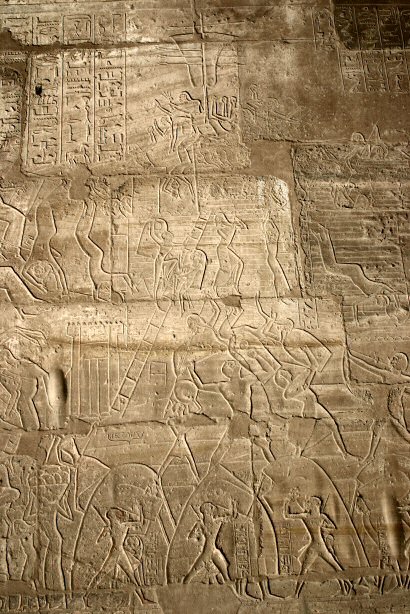

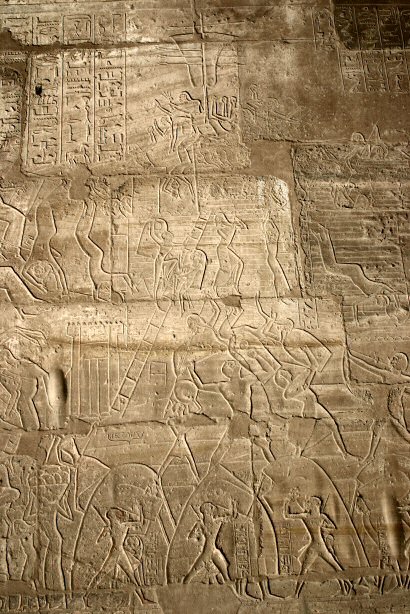

Depictions

The earliest representations of siege warfare have been dated to theProtodynastic Period of Egypt

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating from approximately 3200 to 3000 BC. It is the period during which the process of state formation, which began in Naqada II, became highly visible, ...

, c. 3000 BC. These show the symbolic destruction of city walls by divine animals using hoes.

The first siege equipment is known from Egyptian tomb reliefs of the 24th century BC, showing Egyptian soldiers storming Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ite town walls on wheeled siege ladders. Later Egyptian temple reliefs of the 13th century BC portray the violent siege of Dapur

The siege of Dapur occurred as part of Pharaoh Ramesses II's campaign to suppress Galilee and conquer Syria in 1269 BC. He described his campaign on the wall of his mortuary temple, the Ramesseum in Thebes, Egypt. The inscriptions say that Dapur ...

, a Syrian city, with soldiers climbing scale ladders supported by archers.

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n palace reliefs of the 9th to 7th centuries BC display sieges of several Near Eastern cities. Though a simple battering ram had come into use in the previous millennium, the Assyrians improved siege warfare and used huge wooden tower-shaped battering rams with archers positioned on top.

In ancient China, sieges of city walls (along with naval battles) were portrayed on bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

'hu' vessels, like those found in Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; Simplified Chinese characters, simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively Romanization of Chi ...

, Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

in 1965, which have been dated to the Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

(5th to 3rd centuries BC).Needham, Volume 5, Part 6, 446.

Tactics

Offensive

An attacker's first act in a siege might be a surprise attack, attempting to overwhelm the defenders before they were ready or were even aware there was a threat. This was how William de Forz captured

An attacker's first act in a siege might be a surprise attack, attempting to overwhelm the defenders before they were ready or were even aware there was a threat. This was how William de Forz captured Fotheringhay Castle

Fotheringhay Castle, also known as ''Fotheringay Castle'', was a High Middle Age Norman Motte-and-bailey castle in the village of Fotheringhay to the north of the market town of Oundle, Northamptonshire, England (). It was probably founded a ...

in 1221.

The most common practice of siege warfare was to lay siege and just wait for the surrender of the enemies inside or, quite commonly, to coerce someone inside to betray the fortification. During the medieval period, negotiations would frequently take place during the early part of the siege. An attacker – aware of a prolonged siege's great cost in time, money, and lives – might offer generous terms to a defender who surrendered quickly. The defending troops would be allowed to march away unharmed, often retaining their weapons. However, a garrison commander who was thought to have surrendered too quickly might face execution by his own side for treason.

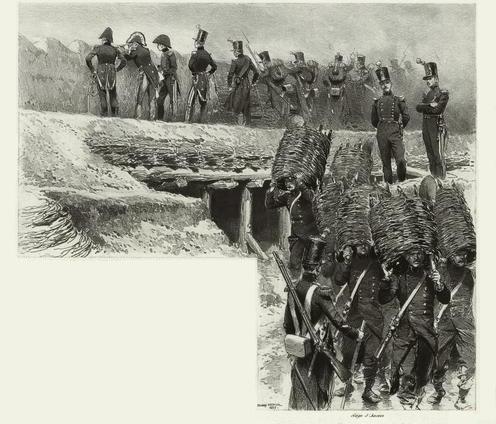

As a siege progressed, the surrounding army would build earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

(a line of circumvallation

Investment is the military process of surrounding an enemy fort (or town) with armed forces to prevent entry or escape. It serves both to cut communications with the outside world and to prevent supplies and reinforcements from being introduced ...

) to completely encircle their target, preventing food, water, and other supplies from reaching the besieged city. If sufficiently desperate as the siege progressed, defenders and civilians might have been reduced to eating anything vaguely edible – horses, family pets, the leather from shoes, and even each other.

The Hittite siege of a rebellious Anatolian vassal in the 14th century BC ended when the queen mother came out of the city and begged for mercy on behalf of her people. The Hittite campaign against the kingdom of Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

in the 14th century BC bypassed the fortified city of Carchemish

Carchemish ( Turkish: ''Karkamış''; or ), also spelled Karkemish ( hit, ; Hieroglyphic Luwian: , /; Akkadian: ; Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ) was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during its ...

. If the main objective of a campaign was not the conquest of a particular city, it could simply be passed by. When the main objective of the campaign had been fulfilled, the Hittite army returned to Carchemish and the city fell after an eight-day siege.

Disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

was another effective siege weapon, although the attackers were often as vulnerable as the defenders. In some instances, catapults or similar weapons were used to fling diseased animals over city walls in an early example of biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

. If all else failed, a besieger could claim the booty of his conquest undamaged, and retain his men and equipment intact, for the price of a well-placed bribe

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corr ...

to a disgruntled gatekeeper. The Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in the 8th century BC came to an end when the Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

bought them off with gifts and tribute, according to the Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n account, or when the Assyrian camp was struck by mass death, according to the Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

account. Due to logistics, long-lasting sieges involving a minor force could seldom be maintained. A besieging army, encamped in possibly squalid field conditions and dependent on the countryside and its own supply lines for food, could very well be threatened with the disease and starvation intended for the besieged.

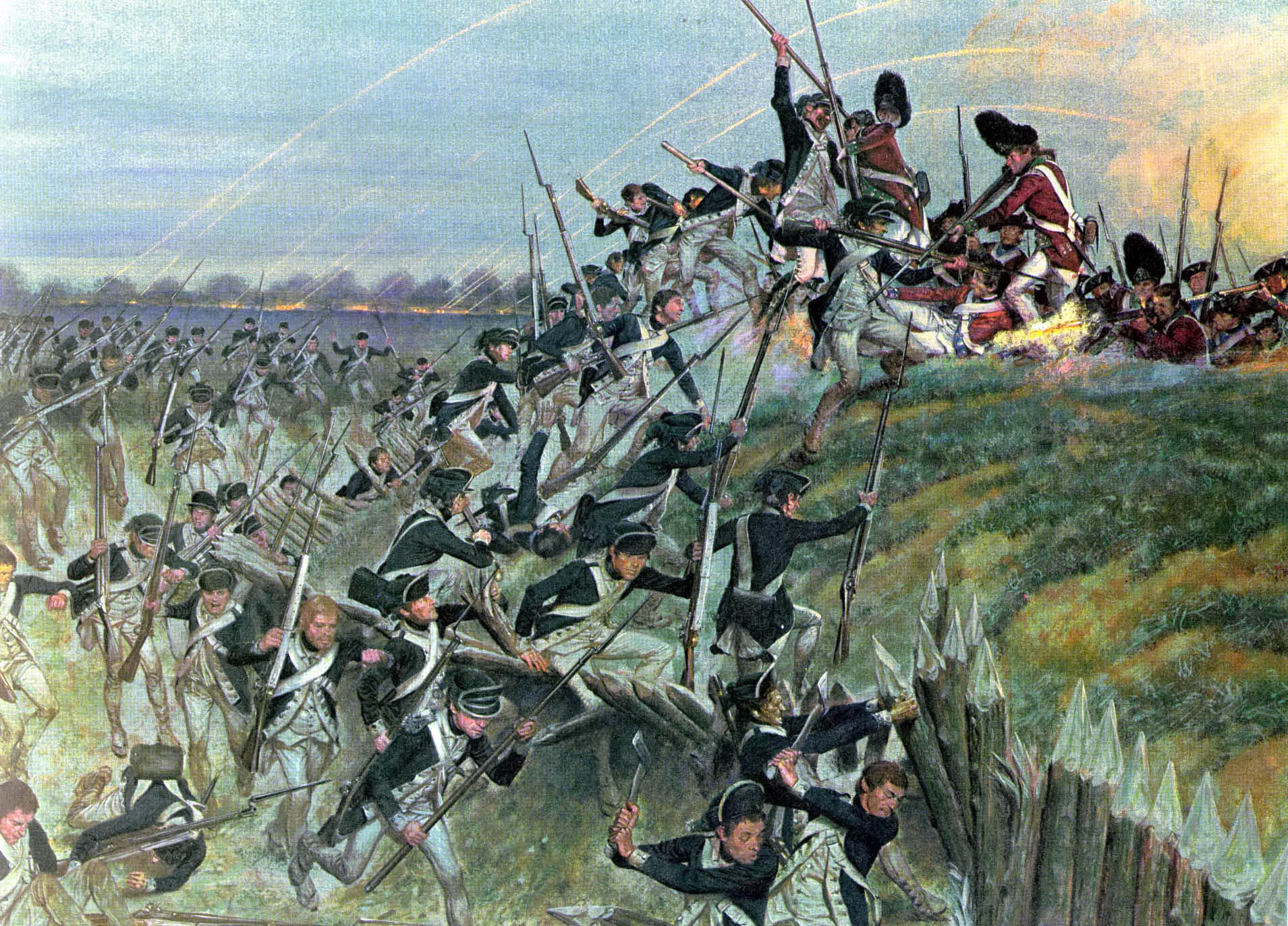

To end a siege more rapidly, various methods were developed in ancient and medieval times to counter fortifications, and a large variety of

To end a siege more rapidly, various methods were developed in ancient and medieval times to counter fortifications, and a large variety of siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while other ...

s was developed for use by besieging armies. Ladders could be used to escalade

{{Unreferenced, date=May 2007

Escalade is the act of scaling defensive walls or ramparts with the aid of ladders. Escalade was a prominent feature of sieges in ancient and medieval warfare, and though it is no longer common in modern warfare, ...

over the defenses. Battering ram

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient history, ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, hea ...

s and siege hook

A siege hook is a weapon used to pull stones from a wall during a siege. The method used was to penetrate the protective wall with the hook and then retract it, pulling away some of the wall with it.

The Greek historian Polybius, in his ''Histor ...

s could also be used to force through gates or walls, while catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored p ...

s, ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ta ...

e, trebuchet

A trebuchet (french: trébuchet) is a type of catapult that uses a long arm to throw a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles of greater weigh ...

s, mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel opera ...

s, and onagers

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

could be used to launch projectiles to break down a city's fortifications and kill its defenders. A siege tower

A Roman siege tower or breaching tower (or in the Middle Ages, a belfry''Castle: Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections''. Dorling Kindersley Pub (T); 1st American edition (September 1994). Siege towers were invented in 300 BC. ) is a specialized siege ...

, a substantial structure built to equal or greater height than the fortification's walls, could allow the attackers to fire down upon the defenders and also advance troops to the wall with less danger than using ladders.

In addition to launching projectiles at the fortifications or defenders, it was also quite common to attempt to undermine the fortifications, causing them to collapse. This could be accomplished by digging a tunnel beneath the foundations

Foundation may refer to:

* Foundation (nonprofit), a type of charitable organization

** Foundation (United States law), a type of charitable organization in the U.S.

** Private foundation, a charitable organization that, while serving a good cause ...

of the walls, and then deliberately collapsing or exploding the tunnel. This process is known as mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

. The defenders could dig counter-tunnels to cut into the attackers' works and collapse them prematurely.

Fire was often used as a weapon when dealing with wooden fortifications. The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

used Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon used by the Eastern Roman Empire beginning . Used to set fire to enemy ships, it consisted of a combustible compound emitted by a flame-throwing weapon. Some historians believe it could be ignited on contact w ...

, which contained additives that made it hard to extinguish. Combined with a primitive flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World ...

, it proved an effective offensive and defensive weapon.

Defensive

The universal method for defending against siege is the use of fortifications, principally walls andditches

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ar ...

, to supplement natural features. A sufficient supply of food and water was also important to defeat the simplest method of siege warfare: starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, dea ...

. On occasion, the defenders would drive 'surplus' civilians out to reduce the demands on stored food and water.

During the Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

in China (481–221 BC), warfare lost its honorable, gentlemen's duty that was found in the previous era of the Spring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

, and became more practical, competitive, cut-throat, and efficient for gaining victory. The Chinese invention of the hand-held, trigger-mechanism crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long fi ...

during this period revolutionized warfare, giving greater emphasis to infantry and cavalry and less to traditional chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nbs ...

warfare.

The philosophically pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

Mohist

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an Chinese philosophy#Ancient philosophy, ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC ...

s (followers of the philosopher Mozi

Mozi (; ; Latinized as Micius ; – ), original name Mo Di (), was a Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (the early portion of the Warring States period, –221 BCE). The ancie ...

) of the 5th century BC believed in aiding the defensive warfare of smaller Chinese states against the hostile offensive warfare of larger domineering states. The Mohists were renowned in the smaller states (and the enemies of the larger states) for the inventions of siege machinery to scale or destroy walls. These included traction trebuchet catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored p ...

s, eight-foot-high ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ta ...

s, a wheeled siege ramp with grappling hook

A grappling hook or grapnel is a device that typically has multiple hooks (known as ''claws'' or ''flukes'') attached to a rope; it is thrown, dropped, sunk, projected, or fastened directly by hand to where at least one hook may catch and hol ...

s known as the Cloud Bridge (the protractible, folded ramp slinging forward by means of a counterweight with rope and pulley), and wheeled 'hook-carts' used to latch large iron hooks onto the tops of walls to pull them down.

When enemies attempted to dig tunnels under walls for mining or entry into the city, the defenders used large

When enemies attempted to dig tunnels under walls for mining or entry into the city, the defenders used large bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtigh ...

(the type the Chinese commonly used in heating up a blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

for smelting cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

) to pump smoke into the tunnels in order to suffocate the intruders.

Advances in the prosecution of sieges in ancient and medieval times naturally encouraged the development of a variety of defensive countermeasures. In particular, medieval fortification

Medieval fortification refers to medieval military methods that cover the development of fortification construction and use in Europe, roughly from the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the Renaissance. During this millennium, fortifications ...

s became progressively stronger—for example, the advent of the concentric castle

A concentric castle is a castle with two or more concentric curtain walls, such that the outer wall is lower than the inner and can be defended from it. The layout was square (at Belvoir and Beaumaris) where the terrain permitted, or an irregu ...

from the period of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

—and more dangerous to attackers—witness the increasing use of machicolation

A machicolation (french: mâchicoulis) is a floor opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement, through which stones or other material, such as boiling water, hot sand, quicklime or boiling cooking oil, could be dropped on attackers at t ...

s and murder-hole

A murder hole or meurtrière is a hole in the ceiling of a gateway or passageway in a fortification through which the defenders could shoot, throw or pour harmful substances or objects such as rocks, arrows, scalding water, hot sand, quicklime ...

s, as well the preparation of hot or incendiary substances. Arrowslit

An arrowslit (often also referred to as an arrow loop, loophole or loop hole, and sometimes a balistraria) is a narrow vertical aperture in a fortification through which an archer can launch arrows or a crossbowman can launch bolts.

The interio ...

s (also called arrow loops or loopholes), sally port

A sally port is a secure, controlled entry way to an enclosure, e.g., a fortification or prison. The entrance is usually protected by some means, such as a fixed wall on the outside, parallel to the door, which must be circumvented to enter an ...

s (airlock-like doors) for sallies and deep water wells were also integral means of resisting siege at this time. Particular attention would be paid to defending entrances, with gates protected by drawbridge

A drawbridge or draw-bridge is a type of moveable bridge typically at the entrance to a castle or tower surrounded by a moat. In some forms of English, including American English, the word ''drawbridge'' commonly refers to all types of moveable ...

s, portcullis

A portcullis (from Old French ''porte coleice'', "sliding gate") is a heavy vertically-closing gate typically found in medieval fortifications, consisting of a latticed grille made of wood, metal, or a combination of the two, which slides down gr ...

es, and barbican

A barbican (from fro, barbacane) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer fortifications, defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe ...

s. Moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

s and other water defenses, whether natural or augmented, were also vital to defenders.

In the European Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, virtually all large cities had city walls—Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterran ...

in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

is a well-preserved example—and more important cities had citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

s, fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s, or castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

s. Great effort was expended to ensure a good water supply inside the city in case of siege. In some cases, long tunnels were constructed to carry water into the city. Complex systems of tunnels were used for storage and communications in medieval cities like Tábor

Tábor (; german: Tabor) is a town in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 33,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

Administrative parts

The followi ...

in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, similar to those used much later in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

Until the invention of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

-based weapons (and the resulting higher-velocity projectiles), the balance of power and logistics definitely favored the defender. With the invention of gunpowder, cannon and mortars and howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s (in modern times), the traditional methods of defense became less effective against a determined siege.

Siege accounts

Although there are numerous ancient accounts of cities being sacked, few contain any clues to how this was achieved. Some popular tales existed on how the cunning heroes succeeded in their sieges. The best-known is theTrojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

of the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

, and a similar story tells how the Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ite city of Joppa was conquered by the Egyptians in the 15th century BC. The Biblical Book of Joshua

The Book of Joshua ( he, סֵפֶר יְהוֹשֻׁעַ ', Tiberian: ''Sēp̄er Yŏhōšūaʿ'') is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament, and is the first book of the Deuteronomistic history, the story of Isra ...

contains the story of the miraculous Battle of Jericho

The Battle of Jericho, as described in the Biblical Book of Joshua, was the first battle fought by the Israelites in the course of the conquest of Canaan. According to , the walls of Jericho fell after the Israelites marched around the city walls ...

.

A more detailed historical account from the 8th century BC, called the Piankhi stela, records how the Nubians

Nubians () (Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of c ...

laid siege to and conquered several Egyptian cities by using battering rams, archers, and slingers and building causeways

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Tr ...

across moats.

Classical antiquity

During thePeloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, one hundred sieges were attempted and fifty-eight ended with the surrender of the besieged area.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

's army successfully besieged many powerful cities during his conquests. Two of his most impressive achievements in siegecraft took place in the siege of Tyre and the siege of the Sogdian Rock

The Sogdian Rock or Rock of Ariamazes, a fortress located north of Bactria in Sogdiana (near Samarkand), ruled by Arimazes, was captured by the forces of Alexander the Great in the early spring of 327 BC as part of his conquest of the Achaemen ...

. His engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

s built a causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Tra ...

that was originally wide and reached the range of his torsion-powered artillery, while his soldiers pushed siege tower

A Roman siege tower or breaching tower (or in the Middle Ages, a belfry''Castle: Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections''. Dorling Kindersley Pub (T); 1st American edition (September 1994). Siege towers were invented in 300 BC. ) is a specialized siege ...

s housing stone throwers and light catapults to bombard the city walls.

Most conquerors before him had found Tyre, a Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n island-city about 1 km from the mainland, impregnable. The Macedonians built a mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole", mammals in the family Talpidae, found in Eurasia and North America

* Golden moles, southern African mammals in the family Chrysochloridae, similar to but unrelated to Talpida ...

, a raised spit of earth across the water, by piling stones up on a natural land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and Colonisation (biology), colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regre ...

that extended underwater to the island, and although the Tyrians rallied by sending a fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

to destroy the towers, and captured the mole in a swarming frenzy, the city eventually fell to the Macedonians after a seven-month siege. In complete contrast to Tyre, Sogdian Rock was captured by stealthy attack. Alexander used commando-like tactics to scale the cliffs and capture the high ground, and the demoralized defenders surrendered.

The importance of siege warfare in the ancient period should not be underestimated. One of the contributing causes of

The importance of siege warfare in the ancient period should not be underestimated. One of the contributing causes of Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

's inability to defeat Rome was his lack of siege engines

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while other ...

, thus, while he was able to defeat Roman armies in the field, he was unable to capture Rome itself. The legionary armies of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

and Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

are noted as being particularly skilled and determined in siege warfare. An astonishing number and variety of sieges, for example, formed the core of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

's mid-1st-century BC conquest of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

(modern France).

In his ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Ca ...

'' (''Commentaries on the Gallic War''), Caesar describes how, at the Battle of Alesia, the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

s created two huge fortified walls around the city. The inner circumvallation, , held in Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix (; Greek: Οὐερκιγγετόριξ; – 46 BC) was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. Despite h ...

's forces, while the outer contravallation

Investment is the military process of surrounding an enemy fort (or town) with armed forces to prevent entry or escape. It serves both to cut communications with the outside world and to prevent supplies and reinforcements from being introduced. ...

kept relief from reaching them. The Romans held the ground in between the two walls. The besieged Gauls, facing starvation, eventually surrendered after their relief force met defeat against Caesar's auxiliary cavalry.

The Sicarii

The Sicarii (Modern Hebrew: סיקריים ''siqariyim'') were a splinter group of the Jewish Zealots who, in the decades preceding Jerusalem's destruction in 70 CE, strongly opposed the Roman occupation of Judea and attempted to expel them and th ...

Zealots

The Zealots were a political movement in 1st-century Second Temple Judaism which sought to incite the people of Judea Province to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Holy Land by force of arms, most notably during the First Jew ...

who defended Masada

Masada ( he, מְצָדָה ', "fortress") is an ancient fortification in the Southern District of Israel situated on top of an isolated rock plateau, akin to a mesa. It is located on the eastern edge of the Judaean Desert, overlooking the Dea ...

in AD 73 were defeated by the Roman legions, who built a ramp 100 m high up to the fortress's west wall.

During the Roman-Persian Wars, siege warfare was extensively being used by both sides.

Medieval period

Arabia during Muhammad's era

The early Muslims, led by theIslamic prophet

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God in Islam, God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. So ...

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

, made extensive use of sieges during military campaigns. The first use was during the Invasion of Banu Qaynuqa

According to Islamic tradition, the invasion of Banu Qaynuqa, also known as the expedition against Banu Qaynuqa, occurred in AD 624. The Banu Qaynuqa were a Jewish tribe expelled by the Islamic prophet Muhammad for breaking the treaty known as t ...

. According to Islamic tradition, the invasion of Banu Qaynuqa occurred in 624 AD. The Banu Qaynuqa were a Jewish tribe expelled by Muhammad for allegedly breaking the treaty known as the Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

. by pinning the clothes of a Muslim woman, which led to her being stripped naked. A Muslim killed a Jew in retaliation, and the Jews in turn killed the Muslim man. This escalated to a chain of revenge killings, and enmity grew between Muslims and the Banu Qaynuqa, leading to the siege of their fortress.. The tribe eventually surrendered to Muhammad, who initially wanted to kill the members of Banu Qaynuqa but ultimately yielded to Abdullah ibn Ubayy

ʿAbd Allāh ibn 'Ubayy ibn Salūl ( ar, عبد الله بن أبي بن سلول), died 631, was a chieftain of the Khazraj tribe of Medina. Upon the arrival of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Ibn Ubayy seemingly became a Muslim, but Muslim tr ...

's insistence and agreed to expel the Qaynuqa..

The second siege was during the Invasion of Banu Nadir

The invasion of Banu Nadir took place in May AD 625 ('' Rabi' al-awwal'', AH) 4. The account is related in Surah Al-Hashr (Chapter 59 - The Gathering) which describes the banishment of the Jewish tribe Banu Nadir who were expelled from Medina aft ...

. According to ''The Sealed Nectar

''Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum'' ( ar, الرحيق المختوم; ), is a seerah book, or biography of the Prophet, which was written by Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri. This book was awarded first prize by the Muslim World League in a worldwide competition ...

'', the siege did not last long; the Banu Nadir Jews willingly offered to comply with the Muhammad's order and leave Madinah. Their caravan counted 600 loaded camels, including their chiefs, Huyai bin Akhtab, and Salam bin Abi Al-Huqaiq, who left for Khaibar, whereas another party shifted to Syria. Two of them embraced Islam, Yameen bin ‘Amr and Abu Sa‘d bin Wahab, and so they retained their personal wealth. Muhammad seized their weapons, land, houses, and wealth. Amongst the other booty he managed to capture, there were 50 armours, 50 helmets, and 340 swords. This booty was exclusively Muhammad's because no fighting was involved in capturing it. He divided the booty at his own discretion among the early Emigrants and two poor Helpers, Abu Dujana and Suhail bin Haneef.online

Other examples include the

Invasion of Banu Qurayza

The Invasion of Banu Qurayza took place in Dhul Qa‘dah during January of CE 627 ( AH 5) and followed on from the Battle of the Trench (Muir, 1861).

The Banu Qurayza initially told the Muslims that they were allied to them during the Battle ...

in February–March 627 and the siege of Ta'if

The siege of Ta'if took place in 630, as the Muslims under the leadership of Muhammad besieged the city of Ta'if after their victory in the battles of Hunayn and Autas. One of the chieftains of Ta'if, Urwah ibn Mas'ud, was absent in Yemen d ...

in January 630. Note: Shawwal 8AH is January 630AD

Mongols and Chinese

In the Middle Ages, theMongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

's campaign against China (then comprising the Western Xia Dynasty

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

, Jin Dynasty, and Southern Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

) by Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

until Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

, who eventually established the Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

in 1271, was very effective, allowing the Mongols to sweep through large areas. Even if they could not enter some of the more well-fortified cities, they used innovative battle tactics to grab hold of the land and the people:

: By concentrating on the field armies, the strongholds had to wait. Of course, smaller fortresses, or ones easily surprised, were taken as they came along. This had two effects. First, it cut off the principal city from communicating with other cities where they might expect aid. Secondly, refugees from these smaller cities would flee to the last stronghold. The reports from these cities and the streaming hordes of refugees not only reduced the morale of the inhabitants and garrison of the principal city, it also strained their resources. Food and water reserves were taxed by the sudden influx of refugees. Soon, what was once a formidable undertaking became easy. The Mongols were then free to lay siege without interference of the field army, as it had been destroyed. At the siege of Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, Hulagu

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Хүлэгү/ , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mongol ruler who conquered much of West ...

used twenty catapults against the ''Bab al-Iraq'' ( Gate of Iraq) alone. In Jûzjânî, there are several episodes in which the Mongols constructed hundreds of siege machines in order to surpass the number which the defending city possessed. While Jûzjânî surely exaggerated, the improbably high numbers which he used for both the Mongols and the defenders do give one a sense of the large numbers of machines used at a single siege.

Another Mongol tactic was to use catapults to launch corpses of plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

victims into besieged cities. The disease-carrying flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s from the bodies would then infest the city, and the plague would spread, allowing the city to be easily captured, although this transmission mechanism was not known at the time. In 1346, the bodies of Mongol warriors of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fr ...

who had died of plague were thrown over the walls of the besieged Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

n city of Kaffa (now Feodosiya

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

). It has been speculated that this operation may have been responsible for the advent of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

in Europe. The Black Death is estimated to have killed 30%–60% of Europe's population.

On the first night while laying siege to a city, the leader of the Mongol forces would lead from a white tent

A tent () is a shelter consisting of sheets of fabric or other material draped over, attached to a frame of poles or a supporting rope. While smaller tents may be free-standing or attached to the ground, large tents are usually anchored using gu ...

: if the city surrendered, all would be spared. On the second day, he would use a red tent: if the city surrendered, the men would all be killed, but the rest would be spared. On the third day, he would use a black tent: no quarter would be given.

However, the Chinese were not completely defenseless, and from AD 1234 until 1279, the Southern Song Chinese held out against the enormous barrage of Mongol attacks. Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (i.e. with early

However, the Chinese were not completely defenseless, and from AD 1234 until 1279, the Southern Song Chinese held out against the enormous barrage of Mongol attacks. Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (i.e. with early flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World ...

s, grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade genera ...

s, firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s, cannons, and land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s) to fight back against the Khitans

The Khitan people (Khitan small script: ; ) were a historical nomadic people from Northeast Asia who, from the 4th century, inhabited an area corresponding to parts of modern Mongolia, Northeast China and the Russian Far East.

As a people desce ...

, the Tanguts