Siege Of Fort Sackville on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Illinois campaign, also known as Clark's Northwestern campaign (1778–1779), was a series of events during the

The Illinois Country was a vaguely defined region which included much of the present U.S. states of

The Illinois Country was a vaguely defined region which included much of the present U.S. states of

Because the Kentucky settlers lacked the authority, manpower, and supplies to launch the expedition themselves, in October 1777 Clark traveled to Williamsburg via the

Because the Kentucky settlers lacked the authority, manpower, and supplies to launch the expedition themselves, in October 1777 Clark traveled to Williamsburg via the

After repeated delays to allow time for more men to join, Clark left Redstone by boat on May 12, 1778, with about 150 recruits, organized in three companies under captains Bowman, Helm, and Harrod.Butterfield, ''History of Clark's Conquest'', 90; James, ''George Rogers Clark'', 115. Clark expected to rendezvous with 200 Holston men under Captain Smith at the

After repeated delays to allow time for more men to join, Clark left Redstone by boat on May 12, 1778, with about 150 recruits, organized in three companies under captains Bowman, Helm, and Harrod.Butterfield, ''History of Clark's Conquest'', 90; James, ''George Rogers Clark'', 115. Clark expected to rendezvous with 200 Holston men under Captain Smith at the

Clark and his men set off from Corn Island on June 24, 1778, leaving behind seven soldiers who were deemed not hardy enough for the journey. These men stayed with the families on the island and guarded the provisions stored there. Clark's force numbered about 175 men, organized in four companies under Captains Bowman, Helm, Harrod, and Montgomery. They passed over the

Clark and his men set off from Corn Island on June 24, 1778, leaving behind seven soldiers who were deemed not hardy enough for the journey. These men stayed with the families on the island and guarded the provisions stored there. Clark's force numbered about 175 men, organized in four companies under Captains Bowman, Helm, Harrod, and Montgomery. They passed over the

On January 29, 1779,

On January 29, 1779,

Clark and his men marched into Vincennes at sunset on February 23, entering the town in two divisions, one commanded by Clark and the other by Bowman. Taking advantage of a slight elevation of land which concealed his men but allowed their flags to be seen, Clark maneuvered his troops to create the impression that 1,000 men were approaching. While Clark and Bowman secured the town, a detachment was sent to begin firing at Fort Sackville after their wet black powder was replaced by local resident François Busseron. Despite the commotion, Hamilton did not realize the fort was under attack until one of his men was wounded by a bullet coming through a window.

Clark had his men build an entrenchment in front of the fort's gate. While men fired at the fort throughout the night, small squads crept up to within of the walls to get a closer shot. The British fired their cannon, destroying a few houses in the city but doing little damage to the besiegers. Clark's men silenced the cannon by firing through the fort's portholes, killing and wounding some of the gunners. Meanwhile, Clark received local help: villagers gave him powder and ammunition they had hidden from the British, and

Clark and his men marched into Vincennes at sunset on February 23, entering the town in two divisions, one commanded by Clark and the other by Bowman. Taking advantage of a slight elevation of land which concealed his men but allowed their flags to be seen, Clark maneuvered his troops to create the impression that 1,000 men were approaching. While Clark and Bowman secured the town, a detachment was sent to begin firing at Fort Sackville after their wet black powder was replaced by local resident François Busseron. Despite the commotion, Hamilton did not realize the fort was under attack until one of his men was wounded by a bullet coming through a window.

Clark had his men build an entrenchment in front of the fort's gate. While men fired at the fort throughout the night, small squads crept up to within of the walls to get a closer shot. The British fired their cannon, destroying a few houses in the city but doing little damage to the besiegers. Clark's men silenced the cannon by firing through the fort's portholes, killing and wounding some of the gunners. Meanwhile, Clark received local help: villagers gave him powder and ammunition they had hidden from the British, and

Clark had high hopes after his recapture of Vincennes. "This stroke", he said, "will nearly put an end to the Indian War." In the coming years of the war, Clark attempted to organize a campaign against Detroit, but each time the expedition was called off because of insufficient men and supplies. Meanwhile, settlers began to pour into Kentucky after hearing news of Clark's victory. In 1779, Virginia opened a land office to register claims in Kentucky, and settlements such as Louisville were established.

After learning of Clark's initial occupation of the Illinois Country, Virginia had claimed the region, establishing

Clark had high hopes after his recapture of Vincennes. "This stroke", he said, "will nearly put an end to the Indian War." In the coming years of the war, Clark attempted to organize a campaign against Detroit, but each time the expedition was called off because of insufficient men and supplies. Meanwhile, settlers began to pour into Kentucky after hearing news of Clark's victory. In 1779, Virginia opened a land office to register claims in Kentucky, and settlements such as Louisville were established.

After learning of Clark's initial occupation of the Illinois Country, Virginia had claimed the region, establishing

Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts (1776–1928). George Rogers Clark Papers, Western Expedition Quartermaster Records, 1778–1784

Accession APA 205. State government records collection,

Links to primary documents online

from the Indiana Historical Bureau, including Clark's memoir, Hamilton's diary, and Bowman's journal.

"Patrick Henry's secret orders to George Rogers Clark"

from the Indiana Historical Society

"Index to the George Rogers Clark Papers – The Illinois Regiment"

from the Sons of the Revolution in the State of Illinois

The Recreated Illinois Regiment – Virginia State Forces (NWTA) organization, American Revolutionary War reenactorsThe Uniform of George Rogers Clark's Illinois Regiment of Virginia State Forces

From October 1778 through February 1779 (The period of the attack on Fort Sackville, Vincennes) {{Authority control 1778 in the United States 1779 in the United States Conflicts in 1778 Conflicts in 1779 Virginia in the American Revolution Campaigns of the American Revolutionary War Illinois in the American Revolution Indiana in the American Revolution Pre-statehood history of Illinois Pre-statehood history of Indiana Battles in the Western theater of the American Revolutionary War Ohio in the American Revolution

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

in which a small force of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

militiamen

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

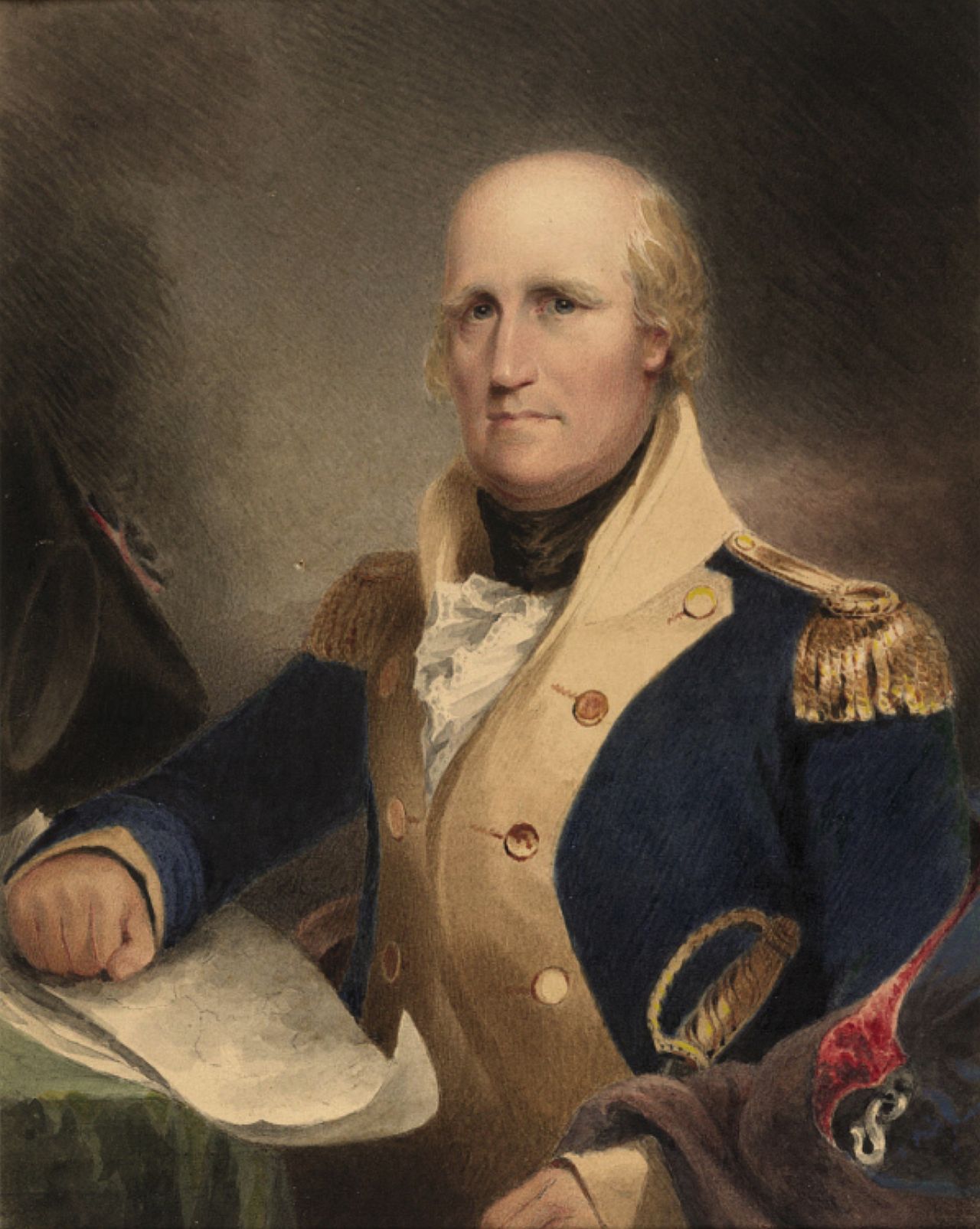

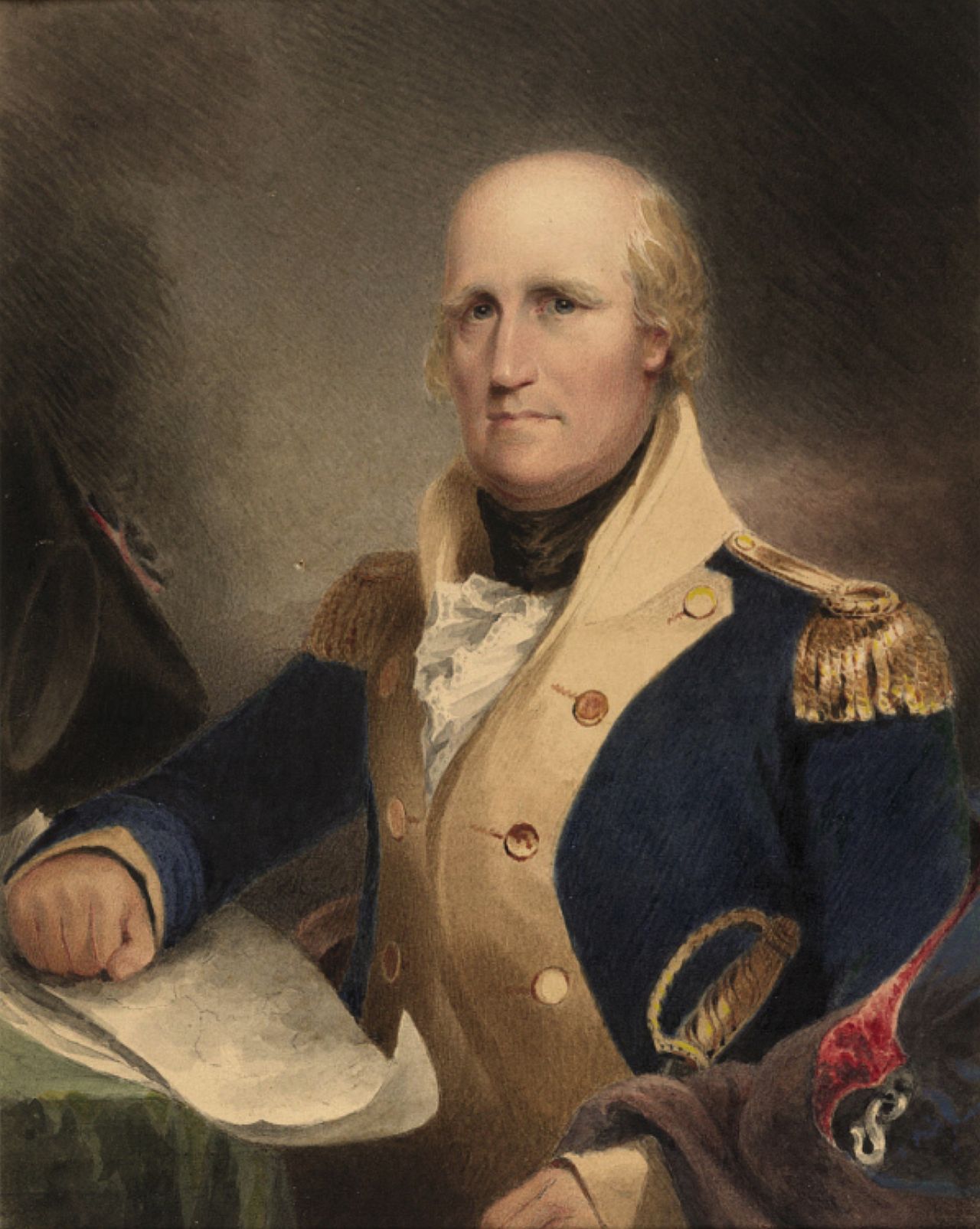

, led by George Rogers Clark

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was an American surveyor, soldier, and militia officer from Virginia who became the highest-ranking American patriot military officer on the northwestern frontier during the Ame ...

, seized control of several British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

posts in the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

of the Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

, in what are now Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

and Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

in the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

. The campaign is the best-known action of the western theater of the war and the source of Clark's reputation as an early American military hero.

In July 1778, Clark and his men crossed the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and took control of Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in t ...

, Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attached ...

, and several other villages in British territory. The occupation was accomplished without firing a shot because many of the Canadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

and Native American inhabitants in the region were unwilling to resist the Patriots. To counter Clark's advance, Henry Hamilton, the British lieutenant governor at Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Detroit (1701–1796) was a fort established on the north bank of the Detroit River by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and the Italian Alphonse de Tonty in 1701. In the 18th century, Fre ...

, reoccupied Vincennes with a small force. In February 1779, Clark returned to Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. Virginia capitalized on Clark's success by establishing the region as Illinois County, Virginia

Illinois County, Virginia, was a political and geographic region, part of the British Province of Quebec, claimed during the American Revolutionary War on July 4, 1778 by George Rogers Clark of the Virginia Militia, as a result of the Illinois C ...

.

The importance of the Illinois campaign has been the subject of much debate. Because the British ceded the entire Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War and overall state of conflict ...

, some historians have credited Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

by seizing control of the Illinois Country during the war. For this reason, Clark was nicknamed the "Conqueror of the Northwest", and his Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized.

Background

The Illinois Country was a vaguely defined region which included much of the present U.S. states of

The Illinois Country was a vaguely defined region which included much of the present U.S. states of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. The area had been a part of the Louisiana district of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

until the end of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

/Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, when France ceded sovereignty of the region to the British in 1763 Treaty of Paris. In the Quebec Act

The Quebec Act 1774 (french: Acte de Québec), or British North America (Quebec) Act 1774, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which set procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec. One of the principal components of the Act w ...

of 1774, the British made the Illinois country a part of its newly expanded Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

.

In 1778, the population of the Illinois Country consisted of about 1,000 people of European descent, mostly French-speaking

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

, and about 600 African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

slaves. Thousands of American Indians lived in villages concentrated along the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, and Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

s. The British military presence was sparse: most of the troops had been withdrawn in 1776 to cut back on expenses. Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave

Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave also, known as, Philippe de Rocheblave and the Chevalier de Rocheblave (March 23, 1727 – April 3, 1802), was a soldier and businessman in the Illinois Country, of Upper Louisiana, and later, a pol ...

, a French-born soldier and official, was hired by the British to be the local commandant, of Fort Gage, in Kaskaskia. Rocheblave reported to Hamilton at Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Detroit (1701–1796) was a fort established on the north bank of the Detroit River by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and the Italian Alphonse de Tonty in 1701. In the 18th century, Fre ...

, and frequently complained that he lacked the money, resources, and troops needed to administer and protect the French villages and forts, from internal and external enemies, within the region.

When the American Revolutionary War began, in 1775, the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

marked the border between the Illinois Country and Kentucky, an area recently settled by American colonists. The British had originally sought to keep American Indians out of the war, but in 1777 Lieutenant Governor Hamilton received instructions to recruit and arm Indian war parties to raid the Kentucky settlements, opening a western front in the war with the rebel colonists. "From 1777 on," wrote historian Bernard Sheehan, "the line of western settlements was under almost constant assault by white-led ndian

Ndian is a department of Southwest Region in Cameroon. It is located in the humid tropical rainforest zone about southeast of Yaoundé, the capital.

History

Ndian division was formed in 1975 from parts of Kumba and Victoria divisions and is ...

raiding parties that had originated at Detroit."

In 1777, George Rogers Clark was a 25-year-old major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

in the Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County (then alternately spelled Kentucke County) was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia from the western portion (beyond the Cumberland Mountains) of Fincastle County effective December 31, 1776. The name of the county was taken ...

, militia. Clark believed that he could end the raids on Kentucky by capturing the British posts in the Illinois Country and then moving against Detroit. In April 1777, Clark sent two spies into the Illinois country. They returned after two months and reported that the fort at Kaskaskia was unguarded, that the French-speaking residents were not greatly attached to the British, and that no one expected an attack from Kentucky. Clark wrote a letter to Governor Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

of Virginia in which he outlined a plan to capture Kaskaskia.

Planning

Because the Kentucky settlers lacked the authority, manpower, and supplies to launch the expedition themselves, in October 1777 Clark traveled to Williamsburg via the

Because the Kentucky settlers lacked the authority, manpower, and supplies to launch the expedition themselves, in October 1777 Clark traveled to Williamsburg via the Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (mo ...

to meet with Governor Henry, joining along the way a party of about 100 settlers who were leaving Kentucky because of the Indian raids. Clark presented his plan to Governor Henry on December 10, 1777. To maintain secrecy, Clark's proposal was only shared with a small group of influential Virginians, including Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including s ...

, and George Wythe

George Wythe (; December 3, 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence from ...

. Although Henry initially expressed doubts about whether the campaign was feasible, Clark managed to win the confidence of Henry and the others. The plan was approved by the members of the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 161 ...

, who were only given vague details about the expedition. Publicly, Clark was authorized to raise men for the defense of Kentucky. In a secret set of instructions from Governor Henry, Clark was instructed to capture Kaskaskia and then proceed as he saw fit.

Governor Henry commissioned Clark as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise seven militia companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

, each to contain fifty men.James, ''George Rogers Clark'', 114. This unit, later known as the Illinois Regiment, was a part of the Virginia State Forces and thus, not a part of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

, the national army of the United States, during the Revolutionary War. The men were enlisted to serve for three months, after they reached Kentucky. To maintain secrecy, Clark did not tell any of his recruits that the purpose of the expedition was to invade the Illinois Country. To raise men and purchase supplies, Clark was given £1,200 in Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' (al ...

currency, which was badly inflated, especially because of British counterfeiting measures at the time.

Clark established his headquarters at Redstone Old Fort Redstone Old Fort — or Redstone Fort

or (for a short time when built) Fort Burd — on the Nemacolin Trail, was the name of the French and Indian War-era wooden fort built in 1759 by Pennsylvania militia colonel James Burd to guard the ancient ...

on the Monongahela River

The Monongahela River ( , )—often referred to locally as the Mon ()—is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 river on the Allegheny Plateau in North Cen ...

, while three of Clark's associates from Dunmore's War, Joseph Bowman, Leonard Helm

Leonard Helm was an American frontiersman and military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. Born around 1720 probably in Fauquier County, Virginia,English, 1:107 he died in poverty while fighting Native American allies of Brit ...

, and William Harrod William Harrod (1753 – 1 January 1819) was an English printer and antiquary, publishing histories of Stamford, Mansfield and Market Harborough.

Life

Harrod was the eldest of five children of a printer and bookseller in Market Harborough, Leicest ...

, each began to recruit men. Clark commissioned Captain William Bailey Smith as a major, and gave him £150 to recruit four companies in the Holston River

The Holston River is a river that flows from Kingsport, Tennessee, to Knoxville, Tennessee. Along with its three major forks (North Fork, Middle Fork and South Fork), it comprises a major river system that drains much of northeastern Tennessee ...

valley and then meet Clark in Kentucky.

For a variety of reasons, Clark was unable to raise all 350 men authorized for the Illinois Regiment. His recruiters had to compete with recruiters from the Continental Army and from other militia units. Some believed that Kentucky was too sparsely inhabited to warrant the diversion of manpower, and recommended that it should be evacuated rather than defended. Settlers in the Holston valley were more concerned with Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

s to the south than with Indians north of the Ohio, and were reluctant to enlist in operations to the north. Although some Pennsylvanians enlisted in the Illinois Regiment, the longstanding boundary dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia meant that few Pennsylvanians volunteered for what was perceived as a campaign to protect Virginia territory.

Clark's journey down the Ohio

After repeated delays to allow time for more men to join, Clark left Redstone by boat on May 12, 1778, with about 150 recruits, organized in three companies under captains Bowman, Helm, and Harrod.Butterfield, ''History of Clark's Conquest'', 90; James, ''George Rogers Clark'', 115. Clark expected to rendezvous with 200 Holston men under Captain Smith at the

After repeated delays to allow time for more men to join, Clark left Redstone by boat on May 12, 1778, with about 150 recruits, organized in three companies under captains Bowman, Helm, and Harrod.Butterfield, ''History of Clark's Conquest'', 90; James, ''George Rogers Clark'', 115. Clark expected to rendezvous with 200 Holston men under Captain Smith at the Falls of the Ohio

The Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area is a national, bi-state area on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky in the United States, administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Federal status was awarded in 1981. The fal ...

in Kentucky. Traveling with Clark's men were about 20 families who were going to Kentucky to settle.

On the journey down the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

, Clark and his men picked up supplies at Forts Pitt and Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

*Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

that were provided by General Edward Hand

Edward Hand (31 December 1744 – 3 September 1802) was an Irish soldier, physician, and politician who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of general, and later was a member of several Pennsy ...

, the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

Western Department commander. They reached Fort Randolph (Point Pleasant, West Virginia

Point Pleasant is a city in and the county seat of Mason County, West Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers. The population was 4,101 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Point Pleasant, ...

) soon after it had been attacked by an Indian war party. The fort commander asked for Clark's help in pursuing the raiders, but Clark declined, believing that he could not spare the time.

As he was nearing the Falls of the Ohio, Clark stopped at the mouth of the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. Commonwealth of Kentuc ...

and sent a message upriver to Major Smith, telling him that it was time to rendezvous. Clark soon learned, however, that of Smith's four promised companies, only one partial company under a Captain Dillard had arrived in Kentucky. Clark therefore sent word to Colonel John Bowman, the senior militia officer in Kentucky, requesting that the colonel send Dillard's men and any other recruits he could find to the falls.

Clark's little flotilla reached the Falls of the Ohio on May 27. He set up a base camp on a small island in the midst of the rapids, later known as Corn Island

The Corn Islands are two islands about east of the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, constituting one of 12 municipalities of the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region. The official name of the municipality is ''Corn Island'' (the English name is ...

. When the additional recruits from Kentucky and Holston finally arrived, Clark added 20 of these men to his force, and sent the others back to Kentucky to help defend the settlements. The new recruits were placed in a company under Captain John Montgomery. In Montgomery's company was a scout named Simon Kenton

Simon Kenton (aka "Simon Butler") (April 3, 1755 – April 29, 1836) was an American frontiersman and soldier in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio. He was a friend of Daniel Boone, Simon Girty, Spencer Records, Thomas S. Hinde, Thomas Hinde, and ...

, who was on his way to becoming a legendary Kentucky frontiersman. On the island, Clark revealed that the real purpose of the expedition was to invade the Illinois country. The news was greeted with enthusiasm by many, but some of the Holston men deserted that night; seven or eight were caught and brought back, but others eluded capture and returned to their homes.

While Clark and his officers drilled the troops in preparation for the Kaskaskia expedition, the families who had traveled with the regiment down the Ohio River settled on the island and planted a corn crop. These settlers moved to the mainland the following year, founding the settlement which became Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

. While on the island, Clark received an important message from Pittsburgh: France had signed a Treaty of Alliance with the United States. Clark hoped that this information would be useful in securing the allegiance of the Canadien inhabitants of the Illinois country.

Occupation of the Illinois Country

Clark and his men set off from Corn Island on June 24, 1778, leaving behind seven soldiers who were deemed not hardy enough for the journey. These men stayed with the families on the island and guarded the provisions stored there. Clark's force numbered about 175 men, organized in four companies under Captains Bowman, Helm, Harrod, and Montgomery. They passed over the

Clark and his men set off from Corn Island on June 24, 1778, leaving behind seven soldiers who were deemed not hardy enough for the journey. These men stayed with the families on the island and guarded the provisions stored there. Clark's force numbered about 175 men, organized in four companies under Captains Bowman, Helm, Harrod, and Montgomery. They passed over the whitewater

Whitewater forms in a rapid context, in particular, when a river's gradient changes enough to generate so much turbulence that air is trapped within the water. This forms an unstable current that froths, making the water appear opaque and ...

of the falls during a total solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

, which some of the men regarded as a good omen.

On June 28, the Illinois Regiment reached the mouth of the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

, where they landed on an island and prepared for the final stage of the journey. Normally, travelers going to Kaskaskia would continue to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, and then paddle upstream to the village. Because Clark hoped to take Kaskaskia by surprise, he decided to march his men across what is now the southern tip of Illinois and approach the village by land, a journey of about . Clark's men captured a boatload of American hunters led by John Duff

John Francis Duff (January 17, 1895 – January 8, 1958) was a Canadian racecar driver who won many races and has been inducted in the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame. He was one of only two Canadians who raced and won on England’s famous Br ...

who had recently been at Kaskaskia; they provided Clark with intelligence about the village and agreed to join the expedition as guides. That evening, Clark and his troops landed their vessels on the north side of the Ohio River, near the ruins of Fort Massac

Fort Massac (or Fort Massiac) was a French colonial and early National-era fort on the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, United States.

Its site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

History

The Spanish explorer ...

, a French fort abandoned after the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(near present Metropolis, Illinois

Metropolis is a city located along the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, United States. It has a population of 6,537 according to the 2010 United States Census. Metropolis is the county seat of Massac County and is part of the Paducah, K ...

).

The men marched through forest before emerging into prairie

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

. When a guide announced that he was lost, Clark suspected treachery and threatened to kill the man unless he found the way. The guide regained his bearings, and the trek resumed. They arrived outside Kaskaskia on the night of July 4. Thinking they would have arrived sooner, the men had carried only four days worth of rations; they had gone without food for the last two days of the six-day march. "In our hungry condition," wrote Joseph Bowman, "we unanimously determined to take the town or die in the attempt."

They crossed the Kaskaskia River

The Kaskaskia River is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 13, 2011 in central and southern Illinois in the Un ...

about midnight and quickly secured the city without firing a shot. At Fort Gage

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, the Virginians captured Rocheblave, who was sleeping in his bed when the Americans burst into the lightly guarded fort. The next morning, Clark worked to secure the allegiance of the townspeople, a task made easier because Clark brought news of the Franco-American alliance. Residents were asked to take oath of loyalty to Virginia and the United States. Father Pierre Gibault

Father Pierre Gibault (7 April 1737 – 16 August 1802) was a Jesuit missionary and priest in the Northwest Territory in the 18th century, and an American Patriot during the American Revolution.

Frontier Missionary

Gibault was born 7 April 1737 a ...

, the village priest, was won over after Clark assured him that the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

would be protected under the laws of Virginia. Rocheblave and several others deemed hostile to the Americans were kept as prisoners and later sent to Virginia.

Clark soon extended his authority to the nearby French settlements. On the afternoon of July 5, Captain Bowman was sent with 30 mounted men, along with some citizens of Kaskaskia, to secure Prairie du Rocher

Prairie du Rocher ("The Rock Prairie" in French) is a village in Randolph County, Illinois, United States. Founded in the French colonial period in the American Midwest, the community is located near bluffs that flank the east side of the Miss ...

, St. Philippe, and Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south-w ...

. The towns offered no resistance, and within 10 days more than 300 people had taken the American oath of allegiance. When Clark turned his attention to Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attached ...

, Father Gibault offered to help. On July 14, Gibault and a few companions set out on horseback for Vincennes. There, most of the citizens agreed to take the oath of allegiance, and the local militia garrisoned Fort Sackville

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the French, British and U.S. forces built and occupied a number of forts at Vincennes, Indiana. These outposts commanded a strategic position on the Wabash River. The names of the installations were change ...

. Gibault returned to Clark in early August to report that Vincennes had been captured and that the American flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the c ...

was now flying at Fort Sackville. Clark dispatched Captain Helm to Vincennes to take command of the Canadien militia.

Hamilton retakes Vincennes

In Detroit, Hamilton learned of Clark's occupation of the Illinois Country by early August 1778. Determined to retake Vincennes, Hamilton gathered about 30 British soldiers, 145 Canadien militiamen, and 60 American Indians underEgushawa Egushawa (c. 1726 – March 1796), also spelled Egouch-e-ouay, Agushaway, Agashawa, Gushgushagwa, Negushwa, and many other variants, was a war chief and principal political chief of the Ottawa tribe of North American Indians. His name is loosely ...

, the influential Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They ha ...

war leader. An advance party of militiamen was led by Captain Normand MacLeod of the Detroit Volunteer Militia. On October 7, Hamilton's main contingent began the journey of more than to Vincennes. Coming down the Wabash, they stopped at Ouiatanon

Fort Ouiatenon, built in 1717, was the first fortified European settlement in what is now Indiana, United States. It was a palisade stockade with log blockhouse used as a French trading post on the Wabash River located approximately three miles ...

and recruited Indians who had declared allegiance to the Americans after Clark's occupation of the Illinois country. By the time Hamilton entered Vincennes on December 17, so many Indians had joined the expedition that his force had increased to 500 men. As Hamilton approached Fort Sackville, the Canadien militia under Captain Helm deserted, leaving the American commander and a few soldiers to surrender. The townsfolk promptly renounced their allegiance to the United States and renewed their oaths to King George.

After the recapture of Vincennes, most of the Indians and Detroit Militia went home. Hamilton settled in at Fort Sackville, for the winter, with a garrison of about 90 soldiers, planning to retake the remaining Illinois towns, along the Mississippi River, in the spring.

Clark's trek to Vincennes

On January 29, 1779,

On January 29, 1779, Francis Vigo

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural Mu ...

, an Italian fur trader, came to Kaskaskia to inform Clark about Hamilton's reoccupation of Vincennes. Clark decided that he needed to launch a surprise winter attack on Vincennes before Hamilton could recapture the Illinois country in the spring. He wrote to Governor Henry:

I know the case is desperate; but, sir, we must either quit the country or attack Mr. Hamilton. No time is to be lost. Were I sure of a reinforcement, I should not attempt it. Who knows what fortune will do for us? Great things have been effected by a few men well conducted. Perhaps we may be fortunate. We have this consolation, that our cause is just, and that our country will be grateful and not condemn our conduct in case we fall through. If we fail, the Illinois as well as Kentucky, I believe, is lost.On February 6, 1779, Clark set out for Vincennes with probably about 170 volunteers, nearly half of them French militia from Kaskaskia. Captain Bowman was second-in-command on the expedition, which Clark characterized as a "

forlorn hope

A forlorn hope is a band of soldiers or other combatants chosen to take the vanguard in a military operation, such as a suicidal assault through the kill zone of a defended position, or the first men to climb a scaling ladder against a defende ...

." While Clark and his men marched across country, 40 men left in an armed row-galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

, which was to be stationed on the Wabash River below Vincennes to prevent the British from escaping by water.

Clark led his men across what is now the state of Illinois, a journey of about . It was not a cold winter, but it rained frequently, and the plains were often covered with several inches of water. Provisions were carried on packhorse

A packhorse, pack horse, or sumpter refers to a horse, mule, donkey, or pony used to carry goods on its back, usually in sidebags or panniers. Typically packhorses are used to cross difficult terrain, where the absence of roads prevents the use of ...

s, supplemented by wild game the men shot as they traveled. They reached the Little Wabash River

:''Note: The Little River of northeastern Indiana is also sometimes known as the Little Wabash River.''

The Little Wabash River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed Ma ...

on February 13, and found it flooded, making a stream about wide. They built a large canoe to shuttle men and supplies across. The next few days were especially trying: provisions were running low, and the men were almost continually wading through water. They reached the Embarras River on February 17. They were now only from Fort Sackville, but the river was too high to ford. They followed the down to the Wabash River, where the next day they began to build boats. Spirits were low: they had been without food for last two days, and Clark struggled to keep men from deserting.

On February 20, five hunters from Vincennes were captured while traveling by boat. They told Clark that his little army had not yet been detected, and that the people of Vincennes were still sympathetic to the Americans. The next day, Clark and his men crossed the Wabash by canoe, leaving their packhorses behind. They marched towards Vincennes, sometimes in water up to their shoulders. The last few days were the hardest: crossing a flooded plain about wide, they used the canoes to shuttle the weary from high point to high point. Shortly before reaching Vincennes, they encountered a villager known to be a friend, who informed Clark that they were still unsuspected. Clark sent the man ahead with a letter to the inhabitants of Vincennes, warning them that he was just about to arrive with an army, and that everyone should stay in their homes unless they wanted to be considered an enemy. The message was read in the public square. No one went to the fort to warn Hamilton.

Siege of Fort Sackville

Clark and his men marched into Vincennes at sunset on February 23, entering the town in two divisions, one commanded by Clark and the other by Bowman. Taking advantage of a slight elevation of land which concealed his men but allowed their flags to be seen, Clark maneuvered his troops to create the impression that 1,000 men were approaching. While Clark and Bowman secured the town, a detachment was sent to begin firing at Fort Sackville after their wet black powder was replaced by local resident François Busseron. Despite the commotion, Hamilton did not realize the fort was under attack until one of his men was wounded by a bullet coming through a window.

Clark had his men build an entrenchment in front of the fort's gate. While men fired at the fort throughout the night, small squads crept up to within of the walls to get a closer shot. The British fired their cannon, destroying a few houses in the city but doing little damage to the besiegers. Clark's men silenced the cannon by firing through the fort's portholes, killing and wounding some of the gunners. Meanwhile, Clark received local help: villagers gave him powder and ammunition they had hidden from the British, and

Clark and his men marched into Vincennes at sunset on February 23, entering the town in two divisions, one commanded by Clark and the other by Bowman. Taking advantage of a slight elevation of land which concealed his men but allowed their flags to be seen, Clark maneuvered his troops to create the impression that 1,000 men were approaching. While Clark and Bowman secured the town, a detachment was sent to begin firing at Fort Sackville after their wet black powder was replaced by local resident François Busseron. Despite the commotion, Hamilton did not realize the fort was under attack until one of his men was wounded by a bullet coming through a window.

Clark had his men build an entrenchment in front of the fort's gate. While men fired at the fort throughout the night, small squads crept up to within of the walls to get a closer shot. The British fired their cannon, destroying a few houses in the city but doing little damage to the besiegers. Clark's men silenced the cannon by firing through the fort's portholes, killing and wounding some of the gunners. Meanwhile, Clark received local help: villagers gave him powder and ammunition they had hidden from the British, and Young Tobacco Young Tobacco was the English name given to a Piankeshaw chief who lived near Post Vincennes during the American Revolution. His influence seems to have extended beyond his own village to all those along the Wabash River.

George Rogers Clark, in ...

, a Piankeshaw

The Piankeshaw, Piankashaw or Pianguichia were members of the Miami tribe who lived apart from the rest of the Miami nation, therefore they were known as Peeyankihšiaki ("splitting off" from the others, Sing.: ''Peeyankihšia'' - "Piankeshaw Pers ...

chief, offered to have his 100 men assist in the attack. Clark declined the chief's offer, fearing that in the darkness his men might mistake the friendly Piankeshaws and Kickapoos

The Kickapoo people ( Kickapoo: ''Kiikaapoa'' or ''Kiikaapoi''; es, Kikapú) are an Algonquian-speaking Native American and Indigenous Mexican tribe, originating in the region south of the Great Lakes. Today, three federally recognized Kickap ...

for one of the enemy tribes that were in the area.

At about 9:00 a.m. on February 24, Clark sent a message to the fort demanding Hamilton's surrender. Hamilton declined, and the firing continued for another two hours until Hamilton sent out his prisoner, Captain Helm, to offer terms. Clark sent Helm back with a demand of unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

within 30 minutes, or else he would storm the fort. Helm returned before the time had expired and presented Hamilton's proposal for a three-day truce. This too was rejected, but Clark agreed to meet Hamilton at the village church.

Before the meeting at the church, the most controversial incident in Clark's career occurred. During these negotiations, a British-allied war party of between 15 and 20 Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They ha ...

and Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

warriors, led by two Canadiens, neared Clark's encampments after leaving the Vincennes Trace

The Vincennes Trace was a major trackway running through what are now the American states of Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. Originally formed by millions of migrating bison, the Trace crossed the Ohio River near the Falls of the Ohio and continue ...

. The party, which escorted two captive Canadien deserters in tow, had been ordered by Hamilton to patrol the nearby area. Having been informed by his Kickapoo allies of the party's movements, Clark ordered a detachment of soldiers under the command of Captain John Williams to capture them. The war party mistakenly assumed Williams and his men were there to escort them into Fort Sackville, and greeted them by discharging their firearms. Williams responded by firing his weapon before seizing one of the Canadien leaders, which led the rest of the party to flee in panic; Williams' men opened fire, killing two, wounding three and capturing eight. The two deserters were released after being captured, and the remaining six captives consisted of a Canadien and five Indians. Clark ordered the five Indians to be murdered before the fort to terrify the British and sow dissension between them and their Indian allies.

At the church, Clark and Bowman met with Hamilton and signed terms of surrender. At 10:00 a.m. on February 25, Hamilton's garrison of 79 men marched out of the fort. Clark's men raised the American flag over the fort and renamed it Fort Patrick Henry. A team of Clark's soldiers and local militia was sent upriver on the Wabash, where a supply convoy was captured, along with British reinforcements and Philippe DeJean Philippe DeJean (1736 – c.1809) was a judge in Fort Detroit until he was captured during the American Revolution.

He was born 5 April 1736 in Toulouse, France, the son of Philippe Dejean and Jeanne de Rocques de Carbouere. His father was a legal ...

, Hamilton's judge in Detroit. Clark sent Hamilton, seven of his officers, and 18 other prisoners to Williamsburg. Canadiens who had accompanied Hamilton were paroled after taking an oath of neutrality.

Aftermath

Clark had high hopes after his recapture of Vincennes. "This stroke", he said, "will nearly put an end to the Indian War." In the coming years of the war, Clark attempted to organize a campaign against Detroit, but each time the expedition was called off because of insufficient men and supplies. Meanwhile, settlers began to pour into Kentucky after hearing news of Clark's victory. In 1779, Virginia opened a land office to register claims in Kentucky, and settlements such as Louisville were established.

After learning of Clark's initial occupation of the Illinois Country, Virginia had claimed the region, establishing

Clark had high hopes after his recapture of Vincennes. "This stroke", he said, "will nearly put an end to the Indian War." In the coming years of the war, Clark attempted to organize a campaign against Detroit, but each time the expedition was called off because of insufficient men and supplies. Meanwhile, settlers began to pour into Kentucky after hearing news of Clark's victory. In 1779, Virginia opened a land office to register claims in Kentucky, and settlements such as Louisville were established.

After learning of Clark's initial occupation of the Illinois Country, Virginia had claimed the region, establishing Illinois County, Virginia

Illinois County, Virginia, was a political and geographic region, part of the British Province of Quebec, claimed during the American Revolutionary War on July 4, 1778 by George Rogers Clark of the Virginia Militia, as a result of the Illinois C ...

in December 1778. In early 1781, Virginia resolved to hand the region over to the central government, paving the way for the final ratification of the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

. These lands became the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

of the United States.

The Illinois campaign was funded in large part by local residents and merchants of the Illinois country. Although Clark submitted his receipts to Virginia, many of these men were never reimbursed. Some of the major contributors, such as Father Gibault, François Riday Busseron François Riday Busseron (Bosseron, Beauceron) was a Canadien fur trader, general store operator, and militia captain in the American village of Vincennes. He supported the Americans during the American Revolution and funded the first American flag ...

, Charles Gratiot

Charles Chouteau Gratiot (August 29, 1786 – May 18, 1855) was born in St. Louis, Spanish Upper Louisiana Territory, now the present-day State of Missouri. He was the son of Charles Gratiot, Sr., a fur trader in the Illinois country during th ...

, and Francis Vigo, would never receive payment during their lifetime, and would be reduced to poverty. However, Clark and his soldiers were given land across from Louisville. This Clark's Grant

Clark's Grant was a tract of land granted in 1781 to George Rogers Clark and the soldiers who fought with him during the American Revolutionary War by the state of Virginia in honor of their service. The tract was and located in present-day Clark ...

was based from what is now Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River and is a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 22,333 at the 2020 census. The town was founded in 1783 by early resident George Rogers Cla ...

and formed much of what would become Clark

Clark is an English language surname, ultimately derived from the Latin with historical links to England, Scotland, and Ireland ''clericus'' meaning "scribe", "secretary" or a scholar within a religious order, referring to someone who was educate ...

and eastern Floyd County, Indiana

Floyd County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. Its county seat is New Albany. Floyd County has the second-smallest land area in the entire state. It was formed in the year 1819 from neighboring Clark, and Harrison counties.

Flo ...

.

In 1789, Clark began to write an account of the Illinois campaign at the request of John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

and other members of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, who were then deliberating how to administer the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. The ''Memoir'', as it usually known, was not published in Clark's lifetime; although used by historians in the 19th century, it was not published in its entirety until 1896, in William Hayden English

William Hayden English (August 27, 1822 – February 7, 1896) was an American politician. He served as a U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1853 to 1861 and was the Democratic Party's nominee for Vice President of the United States in ...

's ''Conquest of the Northwest''. The ''Memoir'' formed the basis of two popular novels, ''Alice of Old Vincennes

''Alice of Old Vincennes'', written by Maurice Thompson in 1900, is a novel set in Vincennes during the American Revolutionary War.

Reception

The book was a popular best-seller. It was the tenth-highest best selling book in the United States in 1 ...

'' (1900) by Maurice Thompson

James Maurice Thompson (September 9, 1844 – February 15, 1901) was an American novelist, poet, essayist, archer and naturalist.

Biography

James Maurice Thompson was born in 1844 in the former town of Fairfield, Indiana, located in Union C ...

, and '' The Crossing'' (1904) by American novelist Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. The Illinois campaign was also depicted in ''Long Knife'', a 1979 historical novel by James Alexander Thom

James Alexander Craig Thom (born May 26, 1933 in Gosport, Indiana) is an American author, best known for his works in the Western genre and colonial American history which are noted for their historical accuracy borne of his painstaking research ...

. The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

has named four ships USS ''Vincennes'' in honor of that battle.

The debate about whether George Rogers Clark "conquered" the Northwest Territory for the United States began soon after the Revolutionary War ended, when the government worked to sort out land claims and war debts. In July 1783, Governor Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

thanked Clark for "wresting so great and valuable a territory out of the hands of the British Enemy...." Clark himself never made such a claim, despairingly writing that he had never captured Detroit. "I have lost the object,” he said. In the 19th century and into the mid-20th century, Clark was frequently referred to as the "Conqueror of the Northwest" in history books. In the 20th century, however, some historians began to doubt that interpretation, arguing that because resource shortages compelled Clark to recall his troops from the Illinois Country before the end of the war, and because most American Indians remained undefeated, there was no "conquest" of the Northwest. It was further argued that Clark's activities had no effect on the boundary negotiations in Europe. In 1940, historian Randolph Downes wrote, "It is misleading to say that Clark 'conquered' the Old Northwest, or that he 'captured' Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes. It would be more accurate to say that he assisted the French and Indian inhabitants of that region to remove themselves from the very shadowy political rule of the British."Downes, ''Council Fires'', 229.

See also

* American Revolutionary War § Mississippi River theater. Places ' Illinois campaign ' in overall sequence and strategic context.Notes

References

;Primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was created at the time under ...

s

*Clark, George Rogers. ''Memoir''. Published under various titles, including ''Col. George Rogers Clark's Sketch of his Campaign in the Illinois in 1778-9'' (New York: Arno, 1971). An edition that standardizes Clark's erratic spelling and grammar for easier reading is ''The Conquest of the Illinois'', edited by Milo M. Quaife (1920; reprinted Southern Illinois University Press, 2001; .)

*Evans, William A., ed. ''Detroit to Fort Sackville, 1778–1779: The Journal of Normand MacLeod''. Wayne State University Press, 1978. .

*James, James Alton, ed. ''George Rogers Clark Papers.'' 2 vols. Originally published 1912–1926. Reprinted New York: AMS Press, 1972. .

*Kellogg, Louise P., ed. ''Frontier Advance on the Upper Ohio, 1778–1779.'' Madison: State Society of Wisconsin, 1916.

*Thwaites, Reuben G. and Louise P. Kellogg, eds. ''Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 1777–1778.'' Originally published 1912; reprinted Millwood, New York: Kraus, 1977. .Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts (1776–1928). George Rogers Clark Papers, Western Expedition Quartermaster Records, 1778–1784

Accession APA 205. State government records collection,

The Library of Virginia

The Library of Virginia in Richmond, Virginia, is the library agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia. It serves as the archival agency and the reference library for Virginia's seat of government. The Library moved into a new building in 1997 and i ...

, Richmond, Virginia.

;

;Secondary source

In Scholarly method, scholarship, a secondary sourcePrimary, secondary and tertiary ...

s

*Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. ''Western Lands and the American Revolution''. Originally published 1937; reprinted New York: Russell & Russell, 1959.

*

*Barnhart, John D. ''Henry Hamilton and George Rogers Clark in the American Revolution, with the Unpublished Journal of Lieut. Governor Henry Hamilton''. Crawfordville, Indiana: Banta, 1951.

*Butterfield, Consul W. ''History of George Rogers Clark's Conquest of the Illinois and the Wabash Towns 1778–1779.'' Columbus, Ohio: Heer, 1903.

*Cayton, Andrew R. L. ''Frontier Indiana''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999. .

*

*Dowd, Gregory Evans. ''A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. .

*Downes, Randolph C. ''Council Fires on the Upper Ohio: A Narrative of Indian Affairs in the Upper Ohio Valley until 1795''. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1940. (1989 reprint).

*English, William Hayden. ''Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778–1783, and Life of Gen. George Rogers Clark''. 2 vols. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1896.

*Harrison, Lowell H. ''George Rogers Clark and the War in the West''. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1976. .

*James, James Alton. ''The Life of George Rogers Clark''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1928.

*———. "The Northwest: Gift or Conquest?" ''Indiana Magazine of History'' 30 (March 1934): 1–15.

*Sheehan, Bernard W. "'The Famous Hair Buyer General': Henry Hamilton, George Rogers Clark, and the American Indian." ''Indiana Magazine of History'' 69 (March 1983): 1–28.

*Smith, Dwight L. "The Old Northwest and the Peace Negotiations" in ''The French, the Indians, and George Rogers Clark in the Illinois Country''. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1977.

* White, Richard. ''The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815''. Cambridge University Press, 1991. .

External links

Links to primary documents online

from the Indiana Historical Bureau, including Clark's memoir, Hamilton's diary, and Bowman's journal.

"Patrick Henry's secret orders to George Rogers Clark"

from the Indiana Historical Society

"Index to the George Rogers Clark Papers – The Illinois Regiment"

from the Sons of the Revolution in the State of Illinois

The Recreated Illinois Regiment – Virginia State Forces (NWTA) organization, American Revolutionary War reenactors

From October 1778 through February 1779 (The period of the attack on Fort Sackville, Vincennes) {{Authority control 1778 in the United States 1779 in the United States Conflicts in 1778 Conflicts in 1779 Virginia in the American Revolution Campaigns of the American Revolutionary War Illinois in the American Revolution Indiana in the American Revolution Pre-statehood history of Illinois Pre-statehood history of Indiana Battles in the Western theater of the American Revolutionary War Ohio in the American Revolution