Siderophores on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity

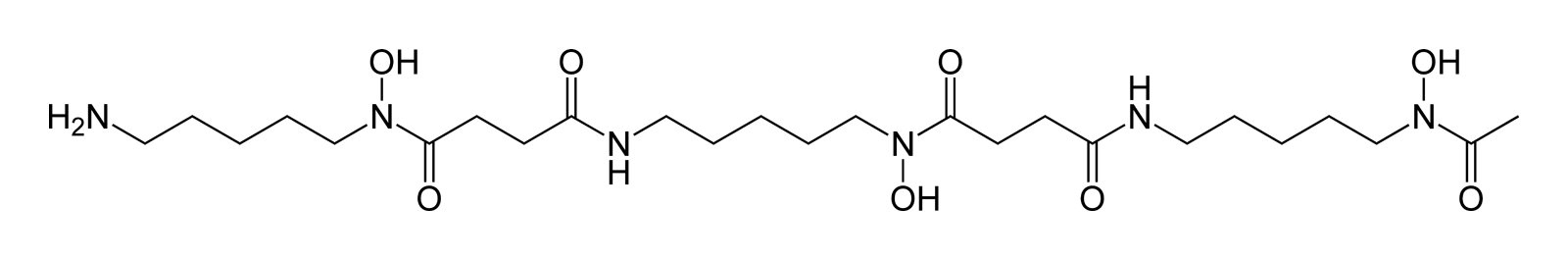

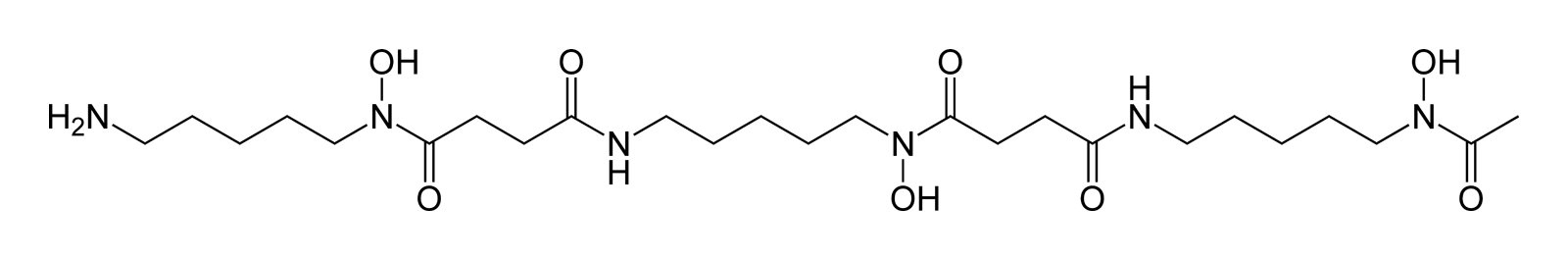

Hydroxamate siderophores

Catecholate siderophores

Mixed ligands

Amino carboxylate ligands

A comprehensive list of siderophore structures (over 250) is presented in Appendix 1 in reference.

Hydroxamate siderophores

Catecholate siderophores

Mixed ligands

Amino carboxylate ligands

A comprehensive list of siderophore structures (over 250) is presented in Appendix 1 in reference.

Although there is sufficient iron in most soils for plant growth, plant iron deficiency is a problem in calcareous soil, due to the low solubility of iron(III) hydroxide. Calcareous soil accounts for 30% of the world's farmland. Under such conditions graminaceous plants (grasses, cereals and rice) secrete phytosiderophores into the soil, a typical example being deoxymugineic acid. Phytosiderophores have a different structure to those of fungal and bacterial siderophores having two α-aminocarboxylate binding centres, together with a single α-hydroxycarboxylate unit. This latter bidentate function provides phytosiderophores with a high selectivity for iron(III). When grown in an iron -deficient soil, roots of graminaceous plants secrete siderophores into the rhizosphere. On scavenging iron(III) the iron–phytosiderophore complex is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane using a proton symport mechanism. The iron(III) complex is then reduced to iron(II) and the iron is transferred to nicotianamine, which although very similar to the phytosiderophores is selective for iron(II) and is not secreted by the roots. Nicotianamine translocates iron in

Although there is sufficient iron in most soils for plant growth, plant iron deficiency is a problem in calcareous soil, due to the low solubility of iron(III) hydroxide. Calcareous soil accounts for 30% of the world's farmland. Under such conditions graminaceous plants (grasses, cereals and rice) secrete phytosiderophores into the soil, a typical example being deoxymugineic acid. Phytosiderophores have a different structure to those of fungal and bacterial siderophores having two α-aminocarboxylate binding centres, together with a single α-hydroxycarboxylate unit. This latter bidentate function provides phytosiderophores with a high selectivity for iron(III). When grown in an iron -deficient soil, roots of graminaceous plants secrete siderophores into the rhizosphere. On scavenging iron(III) the iron–phytosiderophore complex is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane using a proton symport mechanism. The iron(III) complex is then reduced to iron(II) and the iron is transferred to nicotianamine, which although very similar to the phytosiderophores is selective for iron(II) and is not secreted by the roots. Nicotianamine translocates iron in

Most plant pathogens invade the apoplasm by releasing

Most plant pathogens invade the apoplasm by releasing

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

- chelating compounds that are secreted by microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s such as bacteria and fungi. They help the organism accumulate iron. Although a widening range of siderophore functions is now being appreciated. Siderophores are among the strongest (highest affinity) Fe3+ binding agents known. Phytosiderophores are siderophores produced by plants.

Scarcity of soluble iron

Despite being one of the most abundant elements in the Earth's crust, iron is not readily bioavailable. In most aerobic environments, such as the soil or sea, iron exists in the ferric (Fe3+) state, which tends to form insoluble rust-like solids. To be effective, nutrients must not only be available, they must be soluble. Microbes release siderophores to scavenge iron from these mineral phases by formation of soluble Fe3+ complexes that can be taken up by active transport mechanisms. Many siderophores are nonribosomal peptides, although several are biosynthesised independently. Siderophores are also important for some pathogenic bacteria for their acquisition of iron. In mammalian hosts, iron is tightly bound to proteins such ashemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

, transferrin, lactoferrin and ferritin. The strict homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British English, British also homoeostasis) Help:IPA/English, (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physics, physical, and chemistry, chemical conditions maintained by organism, living systems. Thi ...

of iron leads to a free concentration of about 10−24 mol L−1, hence there are great evolutionary pressures put on pathogenic bacteria to obtain this metal. For example, the anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The s ...

pathogen ''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent (obligate) pathogen within the genus '' Bacillus''. Its infection is ...

'' releases two siderophores, bacillibactin and petrobactin, to scavenge ferric ion from iron containing proteins. While bacillibactin has been shown to bind to the immune system protein siderocalin, petrobactin is assumed to evade the immune system and has been shown to be important for virulence in mice.

Siderophores are amongst the strongest binders to Fe3+ known, with enterobactin being one of the strongest of these. Because of this property, they have attracted interest from medical science in metal chelation therapy, with the siderophore desferrioxamine B gaining widespread use in treatments for iron poisoning and thalassemia.

Besides siderophores, some pathogenic bacteria produce ''hemophores'' ( heme binding scavenging proteins) or have receptors that bind directly to iron/heme proteins. In eukaryotes, other strategies to enhance iron solubility and uptake are the acidification of the surroundings (e.g. used by plant roots) or the extracellular reduction of Fe3+ into the more soluble Fe2+ ions.

Structure

Siderophores usually form a stable,hexadentate

A hexadentate ligand in coordination chemistry

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn k ...

, octahedral complex preferentially with Fe3+ compared to other naturally occurring abundant metal ions, although if there are fewer than six donor atoms water can also coordinate. The most effective siderophores are those that have three bidentate ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule ( functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's ele ...

s per molecule, forming a hexadentate complex and causing a smaller entropic change than that caused by chelating a single ferric ion with separate ligands. Fe3+ is a strong Lewis acid, preferring strong Lewis bases such as anionic or neutral oxygen atoms to coordinate with. Microbes usually release the iron from the siderophore by reduction to Fe2+ which has little affinity to these ligands.

Siderophores are usually classified by the ligands used to chelate the ferric iron. The major groups of siderophores include the catecholates (phenolates), hydroxamates and carboxylates (e.g. derivatives of citric acid

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

). Citric acid can also act as a siderophore. The wide variety of siderophores may be due to evolutionary pressures placed on microbes to produce structurally different siderophores which cannot be transported by other microbes' specific active transport systems, or in the case of pathogens deactivated by the host organism.

Diversity

Examples of siderophores produced by variousbacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

and fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

:

Biological function

Bacteria and fungi

In response to iron limitation in their environment, genes involved in microbe siderophore production and uptake are derepressed, leading to manufacture of siderophores and the appropriate uptake proteins. In bacteria, Fe2+-dependent repressors bind to DNA upstream to genes involved in siderophore production at high intracellular iron concentrations. At low concentrations, Fe2+ dissociates from the repressor, which in turn dissociates from the DNA, leading to transcription of the genes. In gram-negative and AT-rich gram-positive bacteria, this is usually regulated by the ''Fur'' (ferric uptake regulator) repressor, whilst in GC-rich gram-positive bacteria (e.g. Actinomycetota) it is ''DtxR'' (diphtheria toxin repressor), so-called as the production of the dangerous diphtheria toxin by '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae'' is also regulated by this system. This is followed by excretion of the siderophore into the extracellular environment, where the siderophore acts to sequester and solubilize the iron. Siderophores are then recognized by cell specific receptors on the outer membrane of the cell. In fungi and other eukaryotes, the Fe-siderophore complex may be extracellularly reduced to Fe2+, while in many cases the whole Fe-siderophore complex is actively transported across the cell membrane. In gram-negative bacteria, these are transported into the periplasm via TonB-dependent receptors, and are transferred into the cytoplasm by ABC transporters. Once in the cytoplasm of the cell, the Fe3+-siderophore complex is usually reduced to Fe2+ to release the iron, especially in the case of "weaker" siderophore ligands such as hydroxamates and carboxylates. Siderophore decomposition or other biological mechanisms can also release iron, especially in the case of catecholates such as ferric-enterobactin, whose reduction potential is too low for reducing agents such as flavin adenine dinucleotide, hence enzymatic degradation is needed to release the iron.Plants

Although there is sufficient iron in most soils for plant growth, plant iron deficiency is a problem in calcareous soil, due to the low solubility of iron(III) hydroxide. Calcareous soil accounts for 30% of the world's farmland. Under such conditions graminaceous plants (grasses, cereals and rice) secrete phytosiderophores into the soil, a typical example being deoxymugineic acid. Phytosiderophores have a different structure to those of fungal and bacterial siderophores having two α-aminocarboxylate binding centres, together with a single α-hydroxycarboxylate unit. This latter bidentate function provides phytosiderophores with a high selectivity for iron(III). When grown in an iron -deficient soil, roots of graminaceous plants secrete siderophores into the rhizosphere. On scavenging iron(III) the iron–phytosiderophore complex is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane using a proton symport mechanism. The iron(III) complex is then reduced to iron(II) and the iron is transferred to nicotianamine, which although very similar to the phytosiderophores is selective for iron(II) and is not secreted by the roots. Nicotianamine translocates iron in

Although there is sufficient iron in most soils for plant growth, plant iron deficiency is a problem in calcareous soil, due to the low solubility of iron(III) hydroxide. Calcareous soil accounts for 30% of the world's farmland. Under such conditions graminaceous plants (grasses, cereals and rice) secrete phytosiderophores into the soil, a typical example being deoxymugineic acid. Phytosiderophores have a different structure to those of fungal and bacterial siderophores having two α-aminocarboxylate binding centres, together with a single α-hydroxycarboxylate unit. This latter bidentate function provides phytosiderophores with a high selectivity for iron(III). When grown in an iron -deficient soil, roots of graminaceous plants secrete siderophores into the rhizosphere. On scavenging iron(III) the iron–phytosiderophore complex is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane using a proton symport mechanism. The iron(III) complex is then reduced to iron(II) and the iron is transferred to nicotianamine, which although very similar to the phytosiderophores is selective for iron(II) and is not secreted by the roots. Nicotianamine translocates iron in phloem

Phloem (, ) is the living tissue in vascular plants that transports the soluble organic compounds made during photosynthesis and known as ''photosynthates'', in particular the sugar sucrose, to the rest of the plant. This transport process is ...

to all plant parts.

Chelating in ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''

Iron is an important nutrient for the bacterium ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'', however, iron is not easily accessible in the environment. To overcome this problem, ''P. aeruginosa'' produces siderophores to bind and transport iron. But the bacterium that produced the siderophores does not necessarily receive the direct benefit of iron intake. Rather all members of the cellular population are equally likely to access the iron-siderophore complexes. The production of siderophores also requires the bacterium to expend energy. Thus, siderophore production can be looked at as an altruistic trait because it is beneficial for the local group but costly for the individual. This altruistic dynamic requires every member of the cellular population to equally contribute to siderophore production. But at times mutations can occur that result in some bacteria producing lower amounts of siderophore. These mutations give an evolutionary advantage because the bacterium can benefit from siderophore production without suffering the energy cost. Thus, more energy can be allocated to growth. Members of the cellular population that can efficiently produce these siderophores are commonly referred to as cooperators; members that produce little to no siderophores are often referred to as cheaters. Research has shown when cooperators and cheaters are grown together, cooperators have a decrease in fitness while cheaters have an increase in fitness. It is observed that the magnitude of change in fitness increases with increasing iron-limitation. With an increase in fitness, the cheaters can outcompete the cooperators; this leads to an overall decrease in fitness of the group, due to lack of sufficient siderophore production.Ecology

Siderophores become important in the ecological niche defined by low iron availability, iron being one of the critical growth limiting factors for virtually all aerobic microorganisms. There are four major ecological habitats: soil and surface water, marine water, plant tissue (pathogens) and animal tissue (pathogens).Soil and surface water

The soil is a rich source of bacterial and fungal genera. Common Gram-positive species are those belonging to the Actinomycetales and species of the genera ''Bacillus'', ''Arthrobacter'' and ''Nocardia''. Many of these organisms produce and secrete ferrioxamines which lead to growth promotion of not only the producing organisms, but also other microbial populations that are able to utilize exogenous siderophores. Soil fungi include ''Aspergillus'' and ''Penicillium'' predominantly produce ferrichromes. This group of siderophores consist of cyclic hexapeptides and consequently are highly resistant to environmental degradation associated with the wide range of hydrolytic enzymes that are present in humic soil. Soils containing decaying plant material possess pH values as low as 3–4. Under such conditions organisms that produce hydroxamate siderophores have an advantage due to the extreme acid stability of these molecules. The microbial population of fresh water is similar to that of soil, indeed many bacteria are washed out from the soil. In addition, fresh-water lakes contain large populations of ''Pseudomonas'', ''Azomonas'', ''Aeromonos'' and ''Alcaligenes'' species.Marine water

In contrast to most fresh-water sources, iron levels in surface sea-water are extremely low (1 nM to 1 μM in the upper 200 m) and much lower than those of V, Cr, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn. Virtually all this iron is in the iron(III) state and complexed to organic ligands. These low levels of iron limit the primary production of phytoplankton and have led to theIron Hypothesis

Iron fertilization is the intentional introduction of iron to iron-poor areas of the ocean surface to stimulate phytoplankton production. This is intended to enhance biological productivity and/or accelerate carbon dioxide () sequestration from ...

where it was proposed that an influx of iron would promote phytoplankton growth and thereby reduce atmospheric CO2. This hypothesis has been tested on more than 10 different occasions and in all cases, massive blooms resulted. However, the blooms persisted for variable periods of time. An interesting observation made in some of these studies was that the concentration of the organic ligands increased over a short time span in order to match the concentration of added iron, thus implying biological origin and in view of their affinity for iron possibly being of a siderophore or siderophore-like nature. Significantly, heterotrophic bacteria were also found to markedly increase in number in the iron-induced blooms. Thus there is the element of synergism between phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria. Phytoplankton require iron (provided by bacterial siderophores), and heterotrophic bacteria require non-CO2 carbon sources (provided by phytoplankton).

The dilute nature of the pelagic marine environment promotes large diffusive losses and renders the efficiency of the normal siderophore-based iron uptake strategies problematic. However, many heterotrophic marine bacteria do produce siderophores, albeit with properties different from those produced by terrestrial organisms. Many marine siderophores are surface-active and tend to form molecular aggregates, for example aquachelins. The presence of the fatty acyl chain renders the molecules with a high surface activity and an ability to form micelles. Thus, when secreted, these molecules bind to surfaces and to each other, thereby slowing the rate of diffusion away from the secreting organism and maintaining a relatively high local siderophore concentration. Phytoplankton have high iron requirements and yet the majority (and possibly all) do not produce siderophores. Phytoplankton can, however, obtain iron from siderophore complexes by the aid of membrane-bound reductases and certainly from iron(II) generated via photochemical decomposition of iron(III) siderophores. Thus a large proportion of iron (possibly all iron) absorbed by phytoplankton is dependent on bacterial siderophore production.

Plant pathogens

Most plant pathogens invade the apoplasm by releasing

Most plant pathogens invade the apoplasm by releasing pectolytic

Pectin lyase (), also known as pectolyase, is a naturally occurring pectinase, a type of enzyme that degrades pectin. It is produced commercially for the food industry from fungi and used to destroy residual fruit starch, known as pectin, in wine ...

enzymes which facilitate the spread of the invading organism. Bacteria frequently infect plants by gaining entry to the tissue via the stomata. Having entered the plant they spread and multiply in the intercellular spaces. With bacterial vascular diseases, the infection is spread within the plants through the xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived fr ...

.

Once within the plant, the bacteria need to be able to scavenge iron from the two main iron-transporting ligands, nicotianamine and citrate. To do this they produce siderophores, thus the enterobacterial ''Erwinia chrysanthemi

''Dickeya dadantii'' is a gram-negative bacillus that belongs to the family Pectobacteriaceae. It was formerly known as ''Erwinia chrysanthemi'' but was reassigned as ''Dickeya dadantii'' in 2005. Members of this family are facultative anaerobes ...

'' produces two siderophores, chrysobactin and achromobactin. '' Xanthomonas'' group of plant pathogens produce xanthoferrin Xanthoferrin is an α-hydroxycarboxylate-type of siderophore produced by xanthomonad

The Xanthomonadales are a bacterial order within the Gammaproteobacteria. They are one of the largest groups of bacterial phytopathogens, harbouring species s ...

siderophores to scavenge the iron.

Like in humans, plants also possess siderophore binding proteins involved in host defense, like the major birch pollen allergen, Bet v 1, which are usually secreted and possess a lipocalin-like structure.

Animal pathogens

Pathogenic bacteria and fungi have developed the means of survival in animal tissue. They may invade the gastro-intestinal tract (''Escherichia'', ''Shigella'' and ''Salmonella''), the lung (''Pseudomonas'', ''Bordatella'', ''Streptococcus'' and ''Corynebacterium''), skin (''Staphylococcus'') or the urinary tract (''Escherichia'' and ''Pseudomonas''). Such bacteria may colonise wounds (''Vibrio'' and ''Staphylococcus'') and be responsible for septicaemia (''Yersinia'' and ''Bacillus''). Some bacteria survive for long periods of time in intracellular organelles, for instance ''Mycobacterium''. (see table). Because of this continual risk of bacterial and fungal invasion, animals have developed a number of lines of defence based on immunological strategies, the complement system, the production of iron–siderophore binding proteins and the general "withdrawal" of iron. There are two major types of iron-binding proteins present in most animals that provide protection against microbial invasion – extracellular protection is achieved by the transferrin family of proteins and intracellular protection is achieved by ferritin. Transferrin is present in the serum at approximately 30 μM, and contains two iron-binding sites, each with an extremely high affinity for iron. Under normal conditions it is about 25–40% saturated, which means that any freely available iron in the serum will be immediately scavenged – thus preventing microbial growth. Most siderophores are unable to remove iron from transferrin. Mammals also produce lactoferrin, which is similar to serum transferrin but possesses an even higher affinity for iron. Lactoferrin is present in secretory fluids, such as sweat, tears and milk, thereby minimising bacterial infection. Ferritin is present in the cytoplasm of cells and limits the intracellular iron level to approximately 1 μM. Ferritin is a much larger protein than transferrin and is capable of binding several thousand iron atoms in a nontoxic form. Siderophores are unable to directly mobilise iron from ferritin. In addition to these two classes of iron-binding proteins, a hormone, hepcidin, is involved in controlling the release of iron from absorptive enterocytes, iron-storing hepatocytes and macrophages. Infection leads to inflammation and the release of interleukin-6 (IL-6 ) which stimulates hepcidin expression. In humans, IL-6 production results in low serum iron, making it difficult for invading pathogens to infect. Such iron depletion has been demonstrated to limit bacterial growth in both extracellular and intracellular locations. In addition to "iron withdrawal" tactics, mammals produce an iron –siderophore binding protein, siderochelin. Siderochelin is a member of the lipocalin family of proteins, which while diverse in sequence, displays a highly conserved structural fold, an 8-stranded antiparallel β-barrel that forms a binding site with several adjacent β-strands. Siderocalin (lipocalin 2) has 3 positively charged residues also located in the hydrophobic pocket, and these create a high affinity binding site for iron(III)–enterobactin. Siderocalin is a potent bacteriostatic agent against ''E. coli''. As a result of infection it is secreted by both macrophages and hepatocytes, enterobactin being scavenged from the extracellular space.Medical applications

Siderophores have applications in medicine for iron and aluminum overload therapy and antibiotics for improved targeting. Understanding the mechanistic pathways of siderophores has led to opportunities for designing small-molecule inhibitors that block siderophore biosynthesis and therefore bacterial growth and virulence in iron-limiting environments. Siderophores are useful as drugs in facilitating iron mobilization in humans, especially in the treatment of iron diseases, due to their high affinity for iron. One potentially powerful application is to use the iron transport abilities of siderophores to carry drugs into cells by preparation of conjugates between siderophores and antimicrobial agents. Because microbes recognize and utilize only certain siderophores, such conjugates are anticipated to have selective antimicrobial activity. An example is the cephalosporin antibiotic cefiderocol. Microbial iron transport (siderophore)-mediated drug delivery makes use of the recognition of siderophores as iron delivery agents in order to have the microbe assimilate siderophore conjugates with attached drugs. These drugs are lethal to the microbe and cause the microbe to apoptosise when it assimilates the siderophore conjugate. Through the addition of the iron-binding functional groups of siderophores into antibiotics, their potency has been greatly increased. This is due to the siderophore-mediated iron uptake system of the bacteria.Agricultural applications

Poaceae (grasses) including agriculturally important species such asbarley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley ...

and wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeolog ...

are able to efficiently sequester iron by releasing phytosiderophores via their root into the surrounding soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

rhizosphere. Chemical compounds produced by microorganisms in the rhizosphere can also increase the availability and uptake of iron. Plants such as oats are able to assimilate iron via these microbial siderophores. It has been demonstrated that plants are able to use the hydroxamate-type siderophores ferrichrome, rhodotorulic acid

Rhodotorulic acid is the smallest of the 2,5-diketopiperazine family of hydroxamate siderophores which are high-affinity chelating agents for ferric iron, produced by bacterial and fungal phytopathogens for scavenging iron from the environment. ...

and ferrioxamine B; the catechol-type siderophores, agrobactin; and the mixed ligand catechol-hydroxamate-hydroxy acid siderophores biosynthesized by saprophytic root-colonizing bacteria. All of these compounds are produced by rhizospheric bacterial strains, which have simple nutritional requirements, and are found in nature in soils, foliage, fresh water, sediments, and seawater.

Fluorescent pseudomonads

The Pseudomonadaceae are a family of bacteria which includes the genera ''Azomonas'', ''Azorhizophilus'', ''Azotobacter'', '' Mesophilobacter'', ''Pseudomonas'' (the type genus), and '' Rugamonas''. The family Azotobacteraceae was recently recl ...

have been recognized as biocontrol agents against certain soil-borne plant pathogens. They produce yellow-green pigments ( pyoverdines) which fluoresce under UV light and function as siderophores. They deprive pathogens of the iron required for their growth and pathogenesis.

Other metal ions chelated

Siderophores, natural or synthetic, can chelate metal ions other than iron ions. Examples includealuminium

Aluminium (aluminum in AmE, American and CanE, Canadian English) is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately o ...

, gallium

Gallium is a chemical element with the symbol Ga and atomic number 31. Discovered by French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1875, Gallium is in group 13 of the periodic table and is similar to the other metals of the group ( alum ...

, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and h ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metals, heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale of mineral hardness#Intermediate ...

, manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy u ...

, cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

, vanadium, zirconium, indium

Indium is a chemical element with the symbol In and atomic number 49. Indium is the softest metal that is not an alkali metal. It is a silvery-white metal that resembles tin in appearance. It is a post-transition metal that makes up 0.21 par ...

, plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhib ...

, berkelium, californium, and uranium.

Related processes

Alternative means of assimilating iron are surface reduction, lowering of pH, utilization of heme, or extraction of protein-complexed metal. Recent data suggest that iron-chelating molecules with similar properties to siderophores, were produced by marine bacteria under phosphate limiting growth condition. In nature phosphate binds to different type of iron minerals, and therefore it was hypothesized that bacteria can use siderophore-like molecules to dissolve such complex in order to access the phosphate.See also

* IonophoreReferences

Further reading

* {{microorganisms Biomolecules Iron metabolism