Sholem Schwarzbard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

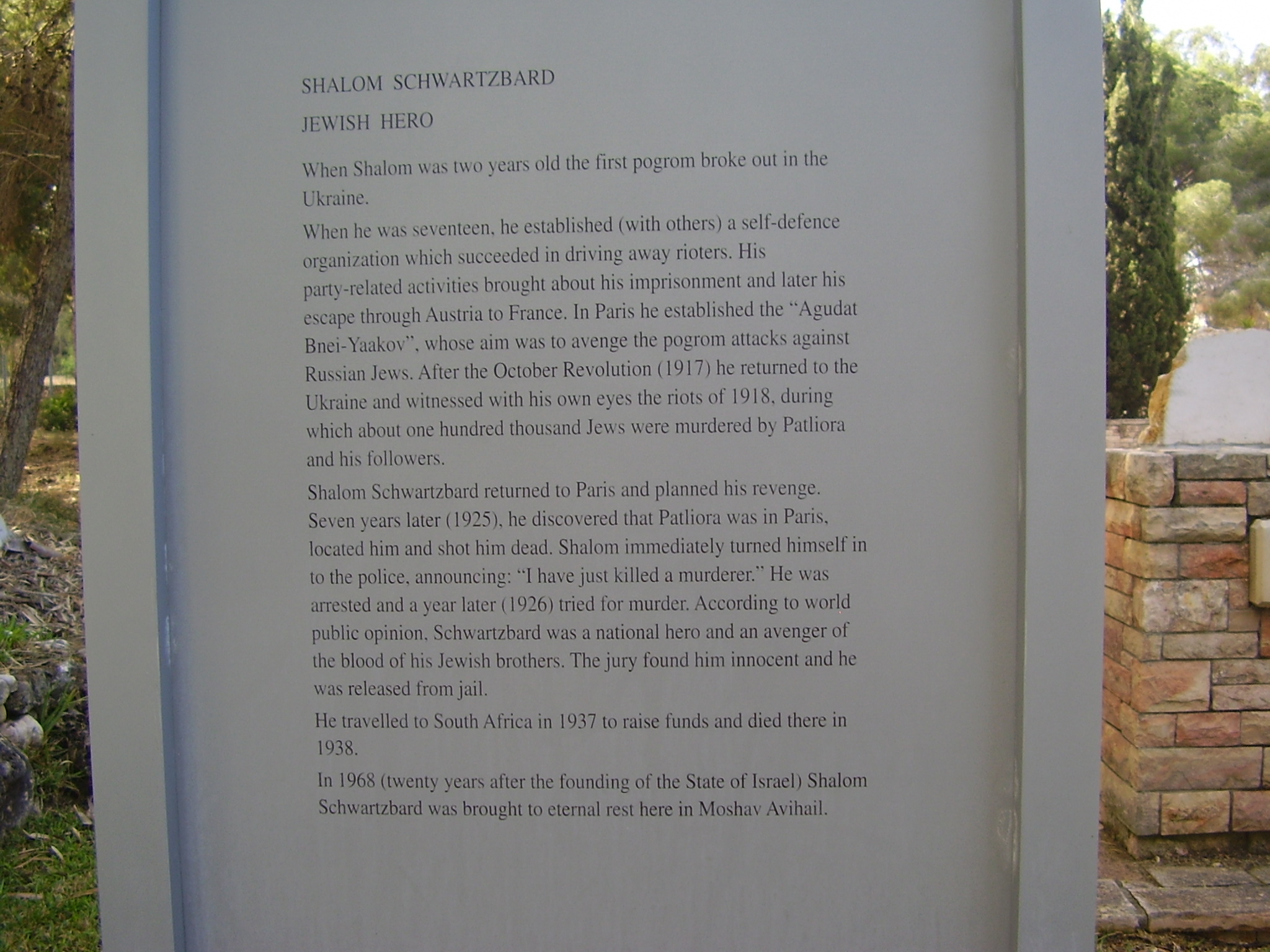

Samuel "Sholem" Schwarzbard (russian: Самуил Исаакович Шварцбурд, ''Samuil Isaakovich Shvartsburd'', yi, שלום שװאַרצבאָרד, french: Samuel 'Sholem' Schwarzbard; 18 August 1886 – 3 March 1938) was a Jewish Russian-born French

Schwarzbard was arrested and was put on trial by the Public Court Committee on 18 October 1927. His defense was led by

Schwarzbard was arrested and was put on trial by the Public Court Committee on 18 October 1927. His defense was led by

"Petlura's Assassin in Hollywood"

"Ukrainian Weekly" article from 6 October 1933 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Schwarzbard, Sholem 1886 births 1938 deaths 20th-century poets Anarchist assassins Bessarabian Jews Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Emigrants from the Russian Empire to South Africa French military personnel of World War I Jewish anarchists People acquitted of murder People from Izmail Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion Soviet military personnel of the Russian Civil War Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian anarchists Ukrainian expatriates in France Ukrainian Jews Yiddish-language poets

Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

. He served in the French and Soviet military, was a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, and is known for organising Jewish community defense against pogroms in pre-First World War era and Russian Civil War era Ukraine, and for the assassination of the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian People' ...

in 1926. He wrote poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

in Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

under the pen name of ''Baal-Khaloymes'' ( en, The Dreamer).

Early life

Schwarzbard was born in 1886 inIzmail

Izmail (, , translit. ''Izmail,'' formerly Тучков ("Tuchkov"); ro, Ismail or ''Smil''; pl, Izmaił, bg, Исмаил) is a city and municipality on the Danube river in Odesa Oblast in south-western Ukraine. It serves as the administra ...

, Bessarabia Governorate

The Bessarabia Governorate (, ) was a part of the Russian Empire from 1812 to 1917. Initially known as Bessarabia Oblast (Бессарабская область, ''Bessarabskaya oblast'') as well as, following 1871, a governorate, it included ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

to the Jewish family of Itskhok Shvartsbard and Khaye Vaysberger. His real given name was Sholem. After the proclamation of an order by the Russian Imperial government for all Jews to move out from the region within of the border, his family moved to the town of Balta

Balta may refer to:

People

* Balta (footballer) (born 1962), Spanish footballer and manager

* Balta (surname)

Places

* Balta (crater), on Mars

* Balta, Mehedinți, Romania

*Bâlta, a village in Filiași, Dolj County, Romania

*Bâlta, a village ...

, in the southern Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

region, where he grew up. His three older brothers died as children and his mother died whilst he was a child. In 1900, at an early age of 14 he became an apprentice to a watchmaker, Israel Dik.

During his apprenticeship in 1903, he became interested in socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and began agitating for a revolutionary group called "Iskra", likely related to Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's journal of the same name. At the time of the first Russian Revolution in 1905, he was based in Kruti, north of Balta, where he was employed, in his own words, "fixing Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

watches". A short time after participating in Jewish-run and -manned paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

activity while visiting his father in Balta, he was arrested and served a short stint in Proskurov

Khmelnytskyi ( uk, Хмельни́цький, Khmelnytskyi, ), until 1954 Proskuriv ( uk, Проску́рів, links=no ), is a city in western Ukraine, the administrative center for Khmelnytskyi Oblast (region) and Khmelnytskyi Raion (dist ...

and Balta prisons. He was released with the general amnesty granted as part of post-revolutionary tsarist "leniency". Fearing further arrests, Schwarzbard fled across the border into Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, where he lived and worked in a number of cities and towns, including the capital, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

. There, he was converted to anarchism, a political philosophy, especially the teachings of Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

, to which he would remain loyal the rest of his life.

France (1910–1917)

In January 1910, at age 23, he settled inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and found work with a series of watchmakers.

First World War and injury

The day before enlisting, he married his girlfriend of three years, Anna Render, a fellow immigrant from Odessa. On 24 August 1914, Schwarzbard and his brother enlisted in theFrench Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

. As a legionnaire, he entered the fray in November 1914 and participated in the Second Battle of Artois

The Second Battle of Artois (french: Deuxième bataille de l'Artois, german: Lorettoschlacht) from 9 May to 18 June 1915, took place on the Western Front during the First World War. A German-held salient from Reims to Amiens had been formed in ...

, near Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

, in May 1915. On account of his excellent military record, in early 1915, he was moved to the regular French 363rd ''régiment d’infanterie'' and transferred south to the Vosges Forest. While there, he was shot through the left lung, fracturing his scapula and tearing his brachial plexus. The doctors gave him little hope of surviving the wound, but he slowly improved over the next year and a half until he was in good enough shape to return to Russia. His left arm was left virtually useless, and he was awarded the Croix de guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

for his courage in the World War

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

.

Russian Revolution (1917–1919)

He was demobilized in August 1917 and in September, traveled with his wife to theRussian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the Decree on the system of government of Russia (1918), 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state (polity), state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territ ...

, established after the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

. On the French boat ''Melbourne'', he was arrested for communist agitation and was handed over to Russian authorities in Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

. He later traveled to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, where he joined and served in the politically mixed Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard lead ...

(1917–1920). Schwarzbard commanded a unit of 90 saber

A sabre ( French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as th ...

s in the brigade of Grigory Kotovsky

Grigory Ivanovich Kotovsky (russian: Григо́рий Ива́нович Кото́вский, ro, Grigore Kotovski; – August 6, 1925) was a Soviet military and political activist, and participant in the Russian Civil War. He made a career ...

.

During the occupation and in the chaos that ensued after the Germans left, Schwarzbard lay low, survived a serious bout with typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

and worked securing facilities and supplies for the newly forming Soviet school system. He had himself tried to establish independent anarchist schools, but was willing to work with the Bolsheviks as they increasingly centralized the school system. Hearing news of countless pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s, Schwarzbard tried to volunteer as a Red Guard soldier. After many delays, he was finally accepted into an "International Brigade" in June 1919 and began his second revolutionary campaign. The next two months were perhaps the worst of his life. His unit suffered defeat from the combined forces of Petliura and Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

, who were uneasy allies at the time. Schwarzbard was in Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

when both the Ukrainian and White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

Armies entered the city, his unit having been wiped out and disbanded. It was in this period, July–August 1919 that Schwarzbard witnessed first-hand the ruins and human devastation left by pogrom violence—images that would haunt him for the rest of his life. He again managed to ride the rails back to Odessa, where he was betrayed by a fellow anarchist to the White forces in control of the city. Before they could catch him, he found out that as a French war veteran, he could catch a ship back to France. In late December 1919 he boarded the ''Nicholas I'' and sailed over Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

and Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

back to Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

. He was back in Paris by 21 January 1920.

In the turmoil that transpired in the period of the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, fourteen members of his family perished in antisemitic pogroms, including his most beloved uncle, who was killed in Ananiv. The names of all fourteen were listed for his trial in 1926 and can be found in the YIVO Schwarzbard Archive.

Return to France (1920–1927)

In 1920, disillusioned with the outcome of the revolution, Sholom moved back toParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

where he opened a clock-and-watch repair shop. There he was active in the French labor movement as an anarchist, and in 1925 became a French citizen. He was acquainted with prominent anarchist activists who had emigrated from Russia and Ukraine, including such figures as Volin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

B ...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, as well as Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

and his follower Peter Arshinov

Peter Andreyevich Arshinov (russian: Пётр Андре́евич Арши́нов; 1887–1937), was a Russian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual who chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina.

Initially a Bolshevik, during the 190 ...

. In Paris Schwarzbard also became a member of the "Union of Ukrainian citizens". He contributed a number of articles to New York's anarchist daily ''Freie Arbeiter Stimme

''Freie Arbeiter Stimme'' ( yi, פֿרייע אַרבעטער שטימע, romanized: ''Fraye arbeṭer shṭime'', ''lit.'' 'Free Voice of Labor') was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between ...

'' under the pseudonym "Sholem"—his first name, but also Yiddish for "peace", a fact he was quite proud of as an avid fan of Count Tolstoy.

Assassination of Petliura (1926)

Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian People' ...

, who was head of the Directorate of the Ukrainian National Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

in 1919, had moved to Paris in 1924 and was the head of the government-in-exile of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

. Sholom Schwarzbard, who had lost his family in the 1919 pogroms, held Symon Petliura responsible for them (see the discussion on Petliura's role in the pogroms). According to his autobiography, after hearing the news that Petliura had relocated to Paris, Schwarzbard became distraught and started plotting Petliura's assassination. Schwarzbard recognized Petliura from a picture.

On 25 May 1926, at 14:12, by the Gibert bookstore, he approached Petliura, who was walking on Rue Racine near Boulevard Saint-Michel

Boulevard Saint-Michel () is one of the two major streets in the Latin Quarter of Paris, the other being Boulevard Saint-Germain. It is a tree-lined boulevard which runs south from the Pont Saint-Michel on the Seine and Place Saint-Michel, cross ...

of the Latin Quarter, Paris

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros ...

, and asked him in Ukrainian, "Are you Mr. Petliura?" Petliura did not answer but raised his cane. Schwarzbard pulled out a gun shooting him five times and, after Petliura fell to the pavement, twice more. When the police came and asked if he had done the deed, he reportedly said, "I have killed a great assassin." Other sources state that he attempted to fire an eighth shot into Petliura, but his firearm jammed.

Schwarzbard trial (1927)

Henri Torrès

Henry Torrès (17 October 1891 – 4 January 1966) was a French trial lawyer and politician, and a prolific writer on political and legal matters.

Family

Henry Torrès was born in Les Andelys in 1891 to a Jewish family. His grandfather, Isaiah ...

, a renowned French jurist who had previously defended anarchists such as Buenaventura Durruti

José Buenaventura Durruti Dumange (14 July 1896 – 20 November 1936) was a Spanish insurrectionary, anarcho-syndicalist militant involved with the CNT and FAI in the periods before and during the Spanish Civil War. Durruti played an in ...

and Ernesto Bonomini Ernesto, form of the name Ernest in several Romance languages, may refer to:

* ''Ernesto'' (novel) (1953), an unfinished autobiographical novel by Umberto Saba, published posthumously in 1975

** ''Ernesto'' (film), a 1979 Italian drama loosely ba ...

and who also represented the Soviet consulate in France.

The core of Schwarzbard's defense was to attempt to show that he was avenging the deaths of victims of pogroms, whereas the prosecution (both criminal and civil) tried to show that Petliura was not responsible for the pogroms and that Schwarzbard was a Soviet agent.

Both sides brought on many witnesses, including several historians. A notable witness for the defence was Haia Greenberg (aged 29), a local nurse who survived the pogroms in Proskurov (now renamed Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine

Khmelnytskyi ( uk, Хмельни́цький, Khmelnytskyi, ), until 1954 Proskuriv ( uk, Проску́рів, links=no ), is a city in western Ukraine, the administrative center for Khmelnytskyi Oblast (oblast, region) and Khmelnytskyi Raio ...

) and testified about the carnage. She never said that Petliura personally participated in the event, but rather some other soldiers who said that they were directed by Petliura. Several former Ukrainian officers testified for the prosecution, including a Red Cross representative who witnessed Semesenko's report to Petliura.

After a trial lasting eight days the jury acquitted Schwarzbard.

Writings

Schwarzbard is the author of numerous books inYiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

published under the pseudonym "Bal Khaloymes": (Dreams and Reality, Paris, 1920), (At War with Myself, Chicago, 1933), (Over the Year, Chicago, 1934).

Sholom Schwarzbard's papers are archived at YIVO

YIVO (Yiddish: , ) is an organization that preserves, studies, and teaches the cultural history of Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe, Germany, and Russia as well as orthography, lexicography, and other studies related to Yiddish. (The word '' ...

Institute for Jewish Research in New York. They were rescued during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and smuggled from France by the historian Zosa Szajkowski.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

*Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian People' ...

, Yevhen Konovalets

Yevhen Mykhailovych Konovalets ( uk, Євген Михайлович Коновалець; June 14, 1891 – May 23, 1938), also anglicized as Eugene Konovalets, was a military commander of the Ukrainian National Republic army, veteran of the Uk ...

, Stepan Bandera

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera ( uk, Степа́н Андрі́йович Банде́ра, Stepán Andríyovych Bandéra, ; pl, Stepan Andrijowycz Bandera; 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian far-right leader of the radical, terr ...

- Three Leaders of Ukrainian Liberation Movement murdered by the Order of Moscow (audiobook).

"Petlura's Assassin in Hollywood"

"Ukrainian Weekly" article from 6 October 1933 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Schwarzbard, Sholem 1886 births 1938 deaths 20th-century poets Anarchist assassins Bessarabian Jews Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Emigrants from the Russian Empire to South Africa French military personnel of World War I Jewish anarchists People acquitted of murder People from Izmail Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion Soviet military personnel of the Russian Civil War Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian anarchists Ukrainian expatriates in France Ukrainian Jews Yiddish-language poets