Ship Construction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Shipbuilding is the

World's Oldest Planked Boats

, in ''

This Old Boat

, 11 December 2000.

Austronesians invented unique ship technologies like catamarans,

Austronesians invented unique ship technologies like catamarans,  The ancestral Austronesian rig was the mastless triangular

The ancestral Austronesian rig was the mastless triangular

Large multi-masted seafaring ships of Southeast Asian Austronesians first started appearing in Chinese records during the

Large multi-masted seafaring ships of Southeast Asian Austronesians first started appearing in Chinese records during the  Austronesians (especially from western Island Southeast Asia) were trading in the

Austronesians (especially from western Island Southeast Asia) were trading in the

Roughly at this time is the last migration wave of the

Roughly at this time is the last migration wave of the

Until recently, Viking

Until recently, Viking

. An insight into shipbuilding in the North Sea/Baltic areas of the early medieval period was found at

Shipbuilders in the

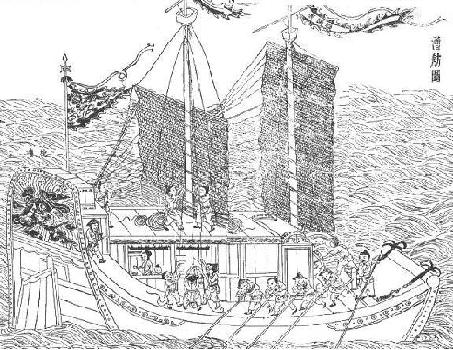

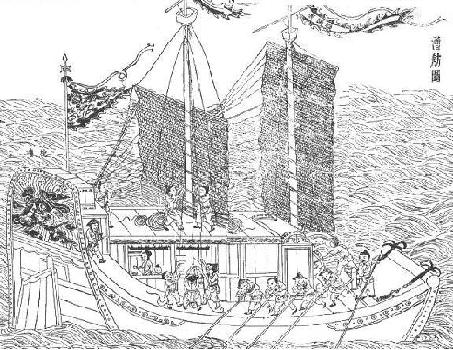

Shipbuilders in the  Several types of ships were built for the voyages, including ''Shachuan'' (沙船), ''Fuchuan'' (福船) and ''Baochuan'' ( treasure ship) (宝船). Zheng He's treasure ships were regarded as ''Shachuan'' types, mainly because they were made in the treasure shipyard in Nanjing. ''Shachuan'', or 'sand-ships', are ships used primarily for inland transport. However, in recent years, some researchers agree that the treasure ships were more of the ''Fuchuan'' type. It is said in vol.176 of ''San Guo Bei Meng Hui Bian'' (三朝北盟汇编) that ships made in Fujian are the best ones. Therefore, the best shipbuilders and laborers were brought from these places to support Zheng He's expedition.

The shipyard was under the command of Ministry of Public Works. The shipbuilders had no control over their lives. The builders, commoner's doctors, cooks and errands had lowest social status. The shipbuilders were forced to move away from their hometown to the shipyards. There were two major ways to enter the shipbuilder occupation: family tradition, or apprenticeship. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation due to family tradition, the shipbuilder learned the techniques of shipbuilding from his family and is very likely to earn a higher status in the shipyard. Additionally, the shipbuilder had access to business networking that could help to find clients. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation through an apprenticeship, the shipbuilder was likely a farmer before he was hired as a shipbuilder, or he was previously an experienced shipbuilder.

Many shipbuilders working in the shipyard were forced into the occupation. The ships built for Zheng He's voyages needed to be waterproof, solid, safe, and have ample room to carry large amounts of trading goods. Therefore, due to the highly commercialized society that was being encouraged by the expeditions, trades, and government policies, the shipbuilders needed to acquire the skills to build ships that fulfil these requirements.

Shipbuilding was not the sole industry utilising Chinese lumber at that time; the new capital was being built in Beijing from approximately 1407 onwards, which required huge amounts of high-quality wood. These two ambitious projects commissioned by Emperor Yongle would have had enormous environmental and economic effects, even if the ships were half the dimensions given in the '' History of Ming''. Considerable pressure would also have been placed on the infrastructure required to transport the trees from their point of origin to the shipyards.

Shipbuilders were usually divided into different groups and had separate jobs. Some were responsible for fixing old ships; some were responsible for making the keel and some were responsible for building the helm.

* It was the

Several types of ships were built for the voyages, including ''Shachuan'' (沙船), ''Fuchuan'' (福船) and ''Baochuan'' ( treasure ship) (宝船). Zheng He's treasure ships were regarded as ''Shachuan'' types, mainly because they were made in the treasure shipyard in Nanjing. ''Shachuan'', or 'sand-ships', are ships used primarily for inland transport. However, in recent years, some researchers agree that the treasure ships were more of the ''Fuchuan'' type. It is said in vol.176 of ''San Guo Bei Meng Hui Bian'' (三朝北盟汇编) that ships made in Fujian are the best ones. Therefore, the best shipbuilders and laborers were brought from these places to support Zheng He's expedition.

The shipyard was under the command of Ministry of Public Works. The shipbuilders had no control over their lives. The builders, commoner's doctors, cooks and errands had lowest social status. The shipbuilders were forced to move away from their hometown to the shipyards. There were two major ways to enter the shipbuilder occupation: family tradition, or apprenticeship. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation due to family tradition, the shipbuilder learned the techniques of shipbuilding from his family and is very likely to earn a higher status in the shipyard. Additionally, the shipbuilder had access to business networking that could help to find clients. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation through an apprenticeship, the shipbuilder was likely a farmer before he was hired as a shipbuilder, or he was previously an experienced shipbuilder.

Many shipbuilders working in the shipyard were forced into the occupation. The ships built for Zheng He's voyages needed to be waterproof, solid, safe, and have ample room to carry large amounts of trading goods. Therefore, due to the highly commercialized society that was being encouraged by the expeditions, trades, and government policies, the shipbuilders needed to acquire the skills to build ships that fulfil these requirements.

Shipbuilding was not the sole industry utilising Chinese lumber at that time; the new capital was being built in Beijing from approximately 1407 onwards, which required huge amounts of high-quality wood. These two ambitious projects commissioned by Emperor Yongle would have had enormous environmental and economic effects, even if the ships were half the dimensions given in the '' History of Ming''. Considerable pressure would also have been placed on the infrastructure required to transport the trees from their point of origin to the shipyards.

Shipbuilders were usually divided into different groups and had separate jobs. Some were responsible for fixing old ships; some were responsible for making the keel and some were responsible for building the helm.

* It was the

Though still largely based on pre-industrial era materials and designs, ships greatly improved during the early

Though still largely based on pre-industrial era materials and designs, ships greatly improved during the early

After

After

Newsletter No. 64, December 2011, In 2022, some key shipbuilders in Europe are

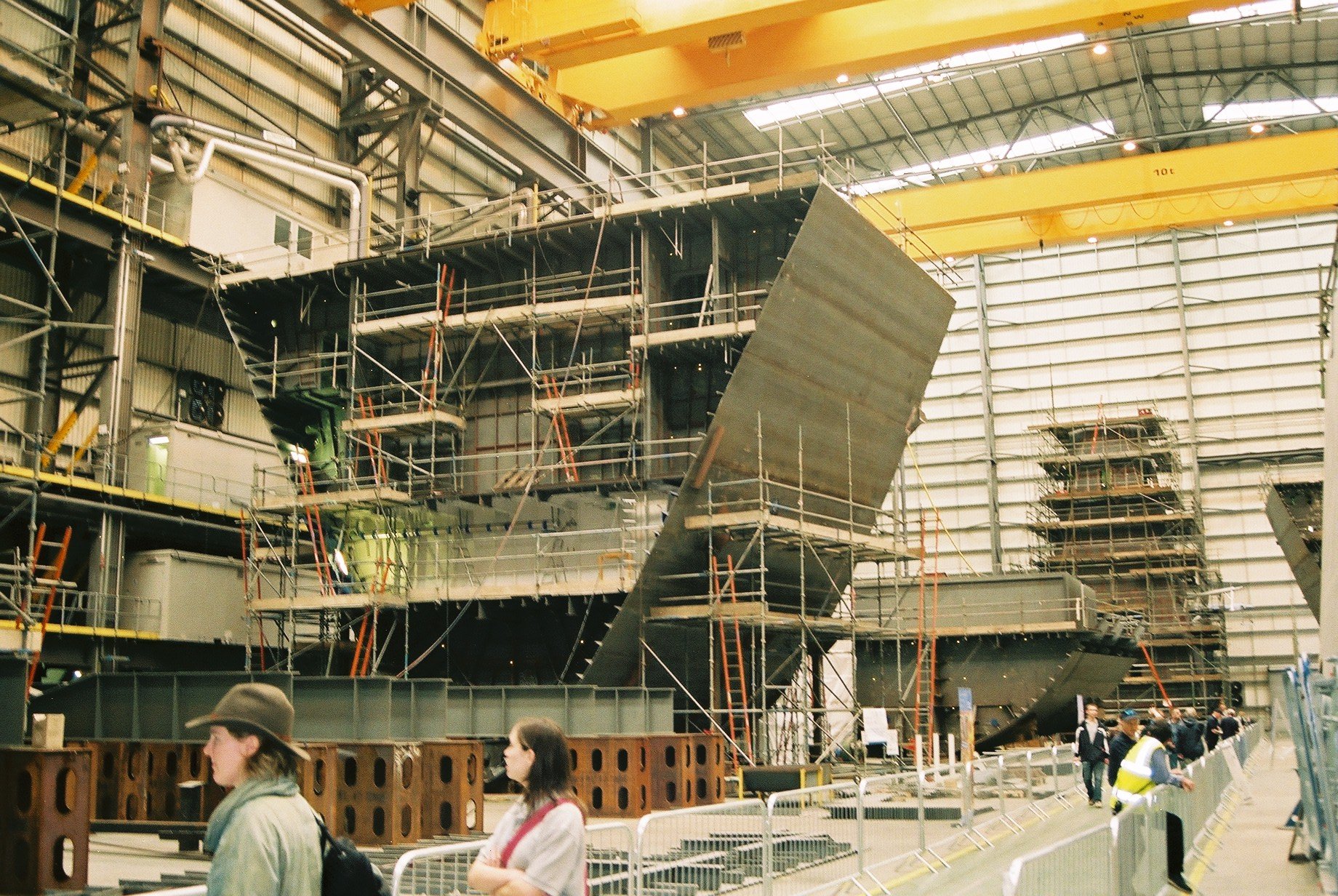

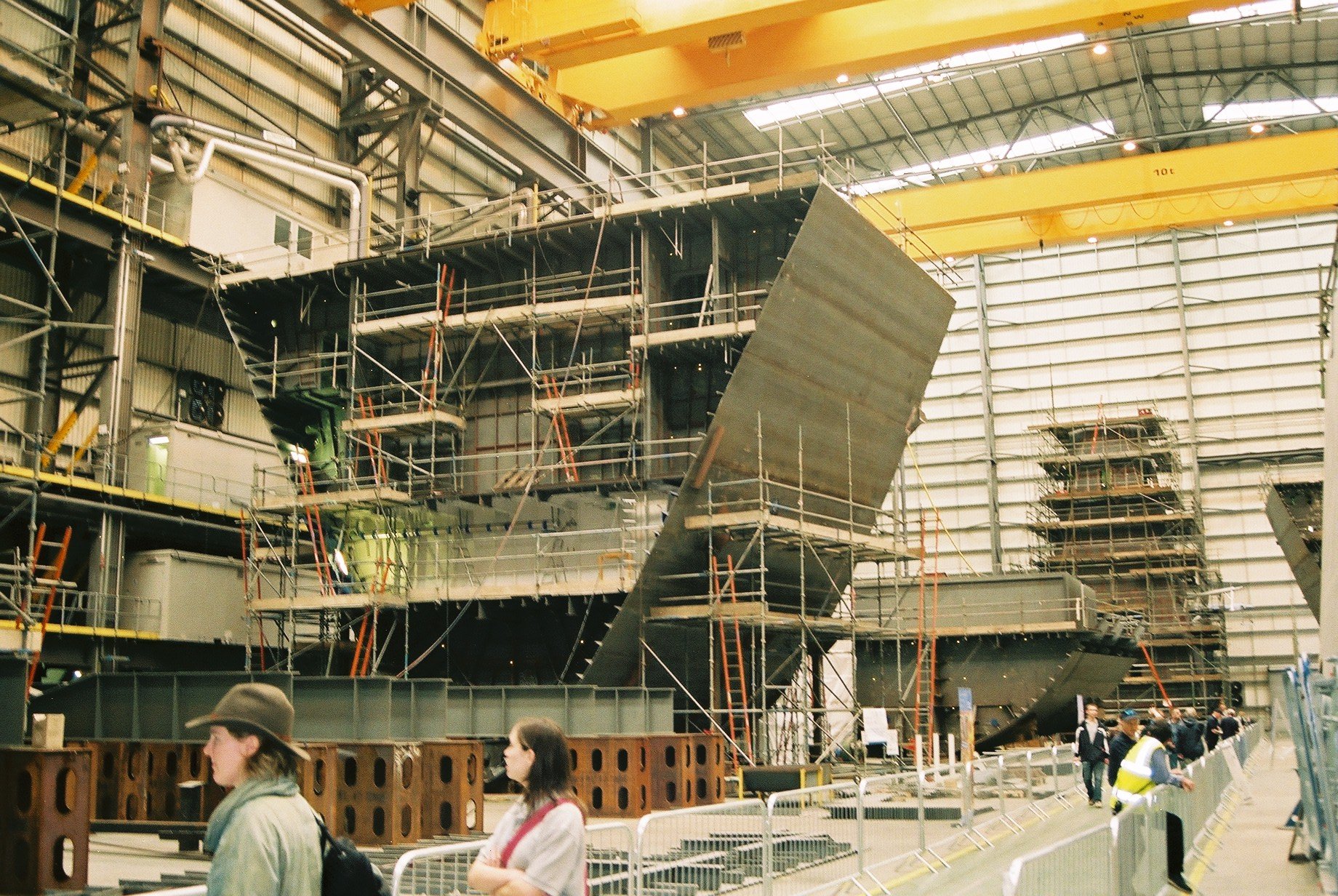

Modern shipbuilding makes considerable use of prefabricated sections. Entire multi-deck segments of the hull or

Modern shipbuilding makes considerable use of prefabricated sections. Entire multi-deck segments of the hull or

All ships need repair work at some point in their working lives. A part of these jobs must be carried out under the supervision of the

All ships need repair work at some point in their working lives. A part of these jobs must be carried out under the supervision of the

Shipbuilding Picture Dictionary

U.S. Shipbuilding

��extensive information about the U.S. shipbuilding industry, including over 500 pages of U.S. shipyard construction records

United States—from GlobalSecurity.org

Shipbuilding News

Bataviawerf – the Historic Dutch East Indiaman Ship Yard

��Shipyard of the historic ships Batavia and Zeven Provincien in the Netherlands, since 1985 here have been great ships reconstructed using old construction methods.

Photos of the reconstruction of the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia

—Photo web site about the reconstruction of the ''Batavia'' on the shipyard Batavia werf, a 16th-century East Indiaman in the Netherlands. The site is constantly expanding with more historic images as in 2010 the shipyard celebrates its 25th year. {{Authority control Naval architecture

construction

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form objects, systems, or organizations,"Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press 2009 and ...

of ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguishe ...

s and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world hi ...

.

Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both commercial and military, are referred to as " naval engineering". The construction of boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size, shape, cargo or passenger capacity, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically found on i ...

s is a similar activity called boat building

Boat building is the design and construction of boats and their systems. This includes at a minimum a hull, with propulsion, mechanical, navigation, safety and other systems as a craft requires.

Construction materials and methods

Wood

W ...

.

The dismantling of ships is called ship breaking

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of parts

Part, parts or PART may refer to:

People

*Armi P� ...

.

History

Pre-history

The earliest known depictions (including paintings and models) of shallow-water sailing boats is from the 6th to 5th millennium BC of the Ubaid period ofMesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

. They were made from bundled reeds coated in bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term ...

and had bipod masts. They sailed in shallow coastal waters of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

.

4th millennium BC

Ancient Egypt

Evidence from Ancient Egypt shows that the early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3100 BC. Egyptian pottery as old as 4000 BC shows designs of early fluvial boats or other means for navigation. TheArchaeological Institute of America

The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) is North America's oldest society and largest organization devoted to the world of archaeology. AIA professionals have carried out archaeological fieldwork around the world and AIA has established re ...

reportsWard, Cheryl.World's Oldest Planked Boats

, in ''

Archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts ...

'' (Volume 54, Number 3, May/June 2009). Archaeological Institute of America

The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) is North America's oldest society and largest organization devoted to the world of archaeology. AIA professionals have carried out archaeological fieldwork around the world and AIA has established re ...

. that some of the oldest ships yet unearthed are known as the Abydos boats. These are a group of 14 ships discovered in Abydos Abydos may refer to:

*Abydos, a progressive metal side project of German singer Andy Kuntz

* Abydos (Hellespont), an ancient city in Mysia, Asia Minor

* Abydos (''Stargate''), name of a fictional planet in the '' Stargate'' science fiction universe ...

that were constructed of wooden planks which were "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, ...

,Schuster, Angela M.H.This Old Boat

, 11 December 2000.

Archaeological Institute of America

The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) is North America's oldest society and largest organization devoted to the world of archaeology. AIA professionals have carried out archaeological fieldwork around the world and AIA has established re ...

. woven strap

A strap, sometimes also called strop, is an elongated flap or ribbon, usually of leather or other flexible materials.

Thin straps are used as part of clothing or baggage, or bedding such as a sleeping bag. See for example spaghetti strap, ...

s were found to have been used to lash the planks together, and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams. Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy, originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC, and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating. The ship dating to 3000 BC was about 75 feet (23 m) long and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh. According to professor O'Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.

Austronesia

The first true ocean-going vessels were built by theAustronesian peoples

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Au ...

during the Austronesian expansion

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austro ...

(c. 3000 BC). From Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

, they first settled the island of Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

before migrating onwards to the rest of Island Southeast Asia and to Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

by 1500 BC, covering distances of thousands of kilometers of open ocean. This was followed by later migrations even further onward; reaching Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

and Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

at its furthest extent, possibly even reaching the Americas.

Austronesians invented unique ship technologies like catamarans,

Austronesians invented unique ship technologies like catamarans, outrigger boat

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull. They can range from small dugout canoes to large plank-built vessels. Outrigger ...

s, lashed-lug

Lashed-lug boats are ancient boat-building techniques of the Austronesian peoples. It is characterized by the use of sewn holes and later dowels ("treenails") to stitch planks edge-to-edge onto a dugout keel and solid carved wood pieces that fo ...

boatbuilding techniques, crab claw sail

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples some time around 1500 BC. It is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures in Isl ...

s, and tanja sails; as well as oceanic navigation techniques. They also invented sewn-plank techniques independently. Austronesian ships varied from simple canoes to large multihull

A multihull is a boat or ship with more than one hull, whereas a vessel with a single hull is a monohull. The most common multihulls are catamarans (with two hulls), and trimarans (with three hulls). There are other types, with four or more ...

ships. The simplest form of all ancestral Austronesian boats had five parts. The bottom part consists of a single piece of hollowed-out log. At the sides were two planks, and two horseshoe-shaped wood pieces formed the prow and stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

. These were fitted tightly together edge-to-edge with dowel

A dowel is a cylindrical rod, usually made of wood, plastic, or metal. In its original manufactured form, a dowel is called a ''dowel rod''. Dowel rods are often cut into short lengths called dowel pins. Dowels are commonly used as structural r ...

s inserted into holes in between, and then lashed to each other with ropes (made from rattan

Rattan, also spelled ratan, is the name for roughly 600 species of Old World climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae. The greatest diversity of rattan palm species and genera are in the closed- canopy old-growth tropical forest ...

or fiber) wrapped around protruding lugs on the planks. This characteristic and ancient Austronesian boatbuilding practice is known as the "lashed-lug

Lashed-lug boats are ancient boat-building techniques of the Austronesian peoples. It is characterized by the use of sewn holes and later dowels ("treenails") to stitch planks edge-to-edge onto a dugout keel and solid carved wood pieces that fo ...

" technique. They were commonly caulk

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on ...

ed with pastes made from various plants as well as tapa bark and fibres which would expand when wet, further tightening joints and making the hull watertight. They formed the shell of the boat, which was then reinforced by horizontal ribs. Shipwrecks of Austronesian ships can be identified from this construction as well as the absence of metal nails. Austronesian ships traditionally had no central rudders but were instead steered using an oar on one side.

The ancestral Austronesian rig was the mastless triangular

The ancestral Austronesian rig was the mastless triangular crab claw sail

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples some time around 1500 BC. It is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures in Isl ...

which had two booms that could be tilted to the wind. These were built in the double-canoe configuration or had a single outrigger on the windward side. In Island Southeast Asia, these developed into double outriggers on each side that provided greater stability. The triangular crab claw sails also later developed into square or rectangular tanja sails, which like crab claw sails, had distinctive booms spanning the upper and lower edges. Fixed masts also developed later in both Southeast Asia (usually as bipod or tripod masts) and Oceania. Austronesians traditionally made their sails from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant pandanus leaves. These sails allowed Austronesians to embark on long-distance voyaging.

The ancient Champa

Champa ( Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ; km, ចាម្ប៉ា; vi, Chiêm Thành or ) were a collection of independent Cham polities that extended across the coast of what is contemporary central and southern Vietnam from approximately the 2nd ...

of Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making it ...

also uniquely developed basket-hulled boats whose hulls were composed of woven and resin

In polymer chemistry and materials science, resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin that is typically convertible into polymers. Resins are usually mixtures of organic compounds. This article focuses on n ...

-caulk

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on ...

ed bamboo, either entirely or in conjunction with plank strakes. They range from small coracles (the '' o thúng'') to large ocean-going trading ships like the ''ghe mành

Ghe or GHE may refer to:

Language

* Ge (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script

* Ghe with upturn, a letter of the Cyrillic script, called Ghe in Ukrainian

* Southern Ghale language, spoken in Nepal

Other uses

* Garachiné Airport, in Panama ...

''.

The acquisition of the catamaran and outrigger technology by the non-Austronesian peoples in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and southern India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union territ ...

is due to the result of very early Austronesian contact with the region, including the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives,, ) and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is a country and archipelagic state in South Asia in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, about from the A ...

and the Laccadive Islands via the Austronesian maritime trade network (the precursor to both the Spice Trade and the Maritime Silk Road

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route is the Maritime history, maritime section of the historic Silk Road that connected Southeast Asia, China, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian peninsula, Somalia, Egypt and Europe. It began by the 2n ...

), estimated to have occurred around 1000 to 600 BCE and onwards. This may have possibly included limited colonization that have since been assimilated. This is still evident in Sri Lankan and South Indian languages. For example, Tamil ''paṭavu'', Telugu

Telugu may refer to:

* Telugu language, a major Dravidian language of India

*Telugu people, an ethno-linguistic group of India

* Telugu script, used to write the Telugu language

** Telugu (Unicode block), a block of Telugu characters in Unicode

S ...

''paḍava'', and Kannada

Kannada (; ಕನ್ನಡ, ), originally romanised Canarese, is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka in southwestern India, with minorities in all neighbouring states. It has around 47 million native s ...

''paḍahu'', all meaning "ship", are all derived from Proto-Hesperonesian *padaw, "sailboat", with Austronesian cognates like Javanese '' perahu'', Kadazan ''padau'', Maranao ''padaw'', Cebuano ''paráw

Paraw (also spelled ''parao'') are various double outrigger sail boats in the Philippines. It is a general term (similar to the term '' bangka'') and thus can refer to a range of ship types, from small fishing canoes to large merchant lashed-lu ...

'', Samoan ''folau'', Hawaiian ''halau'', and Māori ''wharau''.

3rd millennium BC

Ancient Egypt

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The " Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel sealed into a pit in theGiza pyramid complex

The Giza pyramid complex ( ar, مجمع أهرامات الجيزة), also called the Giza necropolis, is the site on the Giza Plateau in Greater Cairo, Egypt that includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of ...

at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Wor ...

in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon

A mortise and tenon (occasionally mortice and tenon) joint connects two pieces of wood or other material. Woodworkers around the world have used it for thousands of years to join pieces of wood, mainly when the adjoining pieces connect at righ ...

joints.

Indus Valley

The oldest known tidal dock in the world was built around 2500 BC during the Harappan civilisation at Lothal near the present day Mangrol harbour on theGujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the nin ...

coast in India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

. Other ports were probably at Balakot

Balakot (; ur, ; ) is a town in Mansehra District in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. The town was destroyed during the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, but was later rebuilt with the assistance of the Government of Pakistan and Saudi Pu ...

and Dwarka. However, it is probable that many small-scale ports, and not massive ports, were used for the Harappan maritime trade. Ships from the harbour at these ancient port cities established trade with Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

. Shipbuilding and boatmaking may have been prosperous industries in ancient India. Native labourers may have manufactured the flotilla of boats used by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

to navigate across the Hydaspes and even the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kash ...

, under Nearchos.Tripathi, page 145 The Indians also exported teak for shipbuilding to ancient Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

. Other references to Indian timber used for shipbuilding is noted in the works of Ibn Jubayr.Hourani & Carswel, page 90

2nd millennium BC

Austronesia

Thecrab claw sail

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples some time around 1500 BC. It is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures in Isl ...

was developed by Austronesians within Island Southeast Asia at around 1500 BC, from the more primitive V-shaped square sails. This is believed to have spurred the invention of the characteristic outriggers of Austronesian vessels, as well as later derivative Austronesian fore-and-aft rigs like the tanja sail and the junk sail.

Mediterranean

The ships of Ancient Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty were typically about 25 meters (80 ft) in length and had a singlemast

Mast, MAST or MASt may refer to:

Engineering

* Mast (sailing), a vertical spar on a sailing ship

* Flagmast, a pole for flying a flag

* Guyed mast, a structure supported by guy-wires

* Mooring mast, a structure for docking an airship

* Radio mast ...

, sometimes consisting of two poles lashed together at the top making an "A" shape. They mounted a single square sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails ma ...

on a yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English unit of length in both the British imperial and US customary systems of measurement equalling 3 feet or 36 inches. Since 1959 it has been by international agreement standardized as exactly 0 ...

, with an additional spar

SPAR, originally DESPAR, styled as DE SPAR, is a Dutch multinational that provides branding, supplies and support services for independently owned and operated food retail stores. It was founded in the Netherlands in 1932, by Adriaan van Well ...

along the bottom of the sail. These ships could also be oar propelled. The ocean- and sea-going ships of Ancient Egypt were constructed with cedar wood, most likely hailing from Lebanon.

The ships of Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

seem to have been of a similar design.

1st millennium BC

Austronesia

Austronesians established the Austronesian maritime trade network (the first true maritime trade network) at around 1000 to 600 BC, linking Southeast Asia with East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and later East Africa. The route later became part of the Spice trade network and theMaritime Silk Road

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route is the Maritime history, maritime section of the historic Silk Road that connected Southeast Asia, China, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian peninsula, Somalia, Egypt and Europe. It began by the 2n ...

. The Austronesian traders introduced Austronesian shipbuilding techniques along the route, leading to the development of South Asian outrigger boat

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull. They can range from small dugout canoes to large plank-built vessels. Outrigger ...

s, the later adoption of the Chinese of the junk sail, and possibly the development of the fore-and-aft Arabic lateen sail.

China

The naval history of China stems back to theSpring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

(722 BC–481 BC) of the ancient Chinese Zhou Dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by ...

. The Chinese built large rectangular barges known as "castle ships", which were essentially floating fortresses complete with multiple decks with guarded rampart

Rampart may refer to:

* Rampart (fortification), a defensive wall or bank around a castle, fort or settlement

Rampart may also refer to:

* "O'er the Ramparts We Watched" is a key line from "The Star-Spangled Banner", the national anthem of the ...

s. However, the Chinese vessels during this era were essentially fluvial (riverine). True ocean-going Chinese fleets did not appear until the 10th century Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

.

Mediterranean

There is considerable knowledge regarding shipbuilding and seafaring in the ancient Mediterranean.1st millennium AD

Austronesia

Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

as the '' k'un-lun po'' or ''kunlun bo'' ("ship of the ''k'un-lun

The Kunlun Mountains ( zh, s=昆仑山, t=崑崙山, p=Kūnlún Shān, ; ug, كۇئېنلۇن تاغ تىزمىسى / قۇرۇم تاغ تىزمىسى ) constitute one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than . In the bro ...

'' ark-skinned southern people). These ships used two types of sail of their invention, the junk sail and tanja sail. Large ships are about 50–60 metres (164–197 ft) long, had tall freeboard, each carrying provisions enough for a year, and could carry 200–1000 people. The Chinese recorded that these Southeast Asian ships were hired for passage to South Asia by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims and travelers, because they did not build seaworthy ships of their own until around the 8–9th century AD.

Austronesians (especially from western Island Southeast Asia) were trading in the

Austronesians (especially from western Island Southeast Asia) were trading in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

as far as Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

during this period. By around 50 to 500 AD, a group of Austronesians, believed to be from the southeastern coasts of Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java Isl ...

(possibly a mixed group related to the modern Ma'anyan, Banjar, and/or the Dayak people

The Dayak (; older spelling: Dajak) or Dyak or Dayuh are one of the native groups of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each ...

) crossed the Indian Ocean and colonized Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. This resulted in the introduction of outrigger canoe technology to non-Austronesian cultures in the East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the histori ...

n coast.

China

The ancient Chinese also built fluvialramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege weapon used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus, ...

vessels as in the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

tradition of the trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean ...

, although oar-steered ships in China lost favor very early on since it was in the 1st century China that the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

-mounted rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw a ...

was first developed. This was dually met with the introduction of the Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

junk ship

A junk (Chinese: 船, ''chuán'') is a type of Chinese sailing ship with fully battened sails. There are two types of junk in China: northern junk, which developed from Chinese river boats, and southern junk, which developed from Austronesian ...

design in the same century. The Chinese were using square sails during the Han dynasty and adopted the Austronesian junk sail later in the 12th century. Iconographic remains show that Chinese ships before the 12th century used square sails, and the junk rig of Chinese ships is believed to be developed from tilted sails.Needham, Joseph (1971). ''Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Southern Chinese junks were based on keeled and multi-planked Austronesian ship known as ''po'' by the Chinese, from the Old Javanese ''parahu'',' Javanese ''prau'', or Malay ''perahu'' — large ship.Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 2012. "Asian ship-building traditions in the Indian Ocean at the dawn of European expansion", in: Om Prakash and D. P. Chattopadhyaya (eds), ''History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian Civilization'', Volume III, part 7: The trading world of the Indian Ocean, 1500-1800, pp. 597-629. Delhi, Chennai, Chandigarh: Pearson. Southern Chinese junks showed characteristics of Austronesian ships that they are made using timbers of tropical origin, with keeled, V-shaped hull. This is different from northern Chinese junks, which are developed from flat-bottomed riverine boats. The northern Chinese junks were primarily built of pine or fir wood, had flat bottoms with no keel, water-tight bulkheads with no frames, transom (squared) stern and stem, and have their planks fastened with iron nails or clamps.

It was unknown when the Chinese people started adopting Southeast Asian (Austronesian) shipbuilding techniques. They may have been started as early as the 8th century, but the development was gradual and the true ocean-going Chinese junks did not appear suddenly. The word "po" survived in Chinese long after, referring to the large ocean-going junks.

Mediterranean

In September 2011, archeological investigations done at the site ofPortus

Portus was a large artificial harbour of Ancient Rome. Sited on the north bank of the north mouth of the Tiber, on the Tyrrhenian coast, it was established by Claudius and enlarged by Trajan to supplement the nearby port of Ostia.

The archaeo ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

revealed inscriptions in a shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

constructed during the reign of Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

(98–117) that indicated the existence of a shipbuilders guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

.

Early 2nd millennium AD

Austronesia

Roughly at this time is the last migration wave of the

Roughly at this time is the last migration wave of the Austronesian expansion

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austro ...

, when the Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n islands spread over vast distances across the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

were being colonized by the (Austronesian) Polynesians from Island Melanesia using double-hulled voyaging catamarans. At its furthest extent, there is a possibility that they may have reached the Americas. After the 11th century, a new type of ship called djong or jong was recorded in Java and Bali. This type of ship was built using wooden dowels and treenails, unlike the ''kunlun bo'' which used vegetal fibres for lashings.

The empire of Majapahit

Majapahit ( jv, ꦩꦗꦥꦲꦶꦠ꧀; ), also known as Wilwatikta ( jv, ꦮꦶꦭ꧀ꦮꦠꦶꦏ꧀ꦠ; ), was a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia that was based on the island of Java (in modern-day Indonesi ...

used jong, built in northern Java, for transporting troops overseas. The jongs were transport ships which could carry 100–2000 tons of cargo and 50–1000 people, 28.99–88.56 meter in length. The exact number of jong fielded by Majapahit is unknown, but the largest number of jong deployed in an expedition is about 400 jongs, when Majapahit attacked Pasai, in 1350.Hill (June 1960). " Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai". ''Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society''. 33: p. 98 and 157: "Then he directed them to make ready all the equipment and munitions of war needed for an attack on the land of Pasai – about four hundred of the largest junks, and also many barges (malangbang) and galleys." See also Nugroho (2011). p. 270 and 286, quoting ''Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai'', 3: 98: "''Sa-telah itu, maka di-suroh baginda musta'idkan segala kelengkapan dan segala alat senjata peperangan akan mendatangi negeri Pasai itu, sa-kira-kira empat ratus jong yang besar-besar dan lain daripada itu banyak lagi daripada malangbang dan kelulus''." (After that, he is tasked by His Majesty to ready all the equipment and all weapons of war to come to that country of Pasai, about four hundred large jongs and other than that much more of malangbang and kelulus.)

Europe

Until recently, Viking

Until recently, Viking longship

Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by the Nors ...

s were seen as marking a very considerable advance on traditional clinker

Clinker may refer to:

*Clinker (boat building), construction method for wooden boats

*Clinker (waste), waste from industrial processes

*Clinker (cement), a kilned then quenched cement product

* ''Clinkers'' (album), a 1978 album by saxophonist St ...

-built hulls of plank boards tied together with leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and ho ...

thongs. This consensus has recently been challenged. Haywood has argued that earlier Frankish and Anglo-Saxon nautical practice was much more accomplished than had been thought and has described the distribution of clinker ''vs.'' carvel construction in Western Europe (see ma. An insight into shipbuilding in the North Sea/Baltic areas of the early medieval period was found at

Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...

, England, where a ship was buried with a chieftain. The ship was long and wide. Upward from the keel, the hull was made by overlapping nine strakes on either side with rivets fastening the oaken planks together. It could hold upwards of thirty men.

Sometime around the 12th century, northern European ships began to be built with a straight sternpost

A sternpost is the upright structural member or post at the stern of a (generally wooden) ship or a boat, to which are attached the transoms and the rearmost left corner part of the stern.

The sternpost may either be completely vertical or m ...

, enabling the mounting of a rudder, which was much more durable than a steering oar held over the side. Development in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

favored "round ships", with a broad beam and heavily curved at both ends. Another important ship type was the galley, which was constructed with both sails and oars.

The first extant treatise on shipbuilding was written c. 1436 by Michael of Rhodes, a man who began his career as an oarsman on a Venetian galley in 1401 and worked his way up into officer positions. He wrote and illustrated a book that contains a treatise on shipbuilding, a treatise on mathematics, much material on astrology, and other materials. His treatise on shipbuilding treats three kinds of galleys and two kinds of round ships.

China

Shipbuilders in the

Shipbuilders in the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(1368~1644) were not the same as the shipbuilders in other Chinese dynasties, due to hundreds of years of accumulated experiences and rapid changes in the Ming dynasty. Shipbuilders in the Ming dynasty primarily worked for the government, under command of the Ministry of Public Works.

During the early years of the Ming dynasty, the Ming government maintained an open policy towards sailing. Between 1405 and 1433, the government conducted seven diplomatic Ming treasure voyages

The Ming treasure voyages were the seven maritime expeditions undertaken by Ming China's treasure fleet between 1405 and 1433. The Yongle Emperor ordered the construction of the treasure fleet in 1403. The grand project resulted in far-reach ...

to over thirty countries in Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East and Eastern Africa. The voyages were initiated by the Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

, and led by the Admiral Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferre ...

. Six voyages were conducted under the Yongle Emperor's reign, the last of which returned to China in 1422. After the Yongle Emperor's death in 1424, his successor the Hongxi Emperor

The Hongxi Emperor (16 August 1378 – 29 May 1425), personal name Zhu Gaochi (朱高熾), was the fourth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1424 to 1425. He succeeded his father, the Yongle Emperor, in 1424. His era name " Hongxi" mean ...

ordered the suspension of the voyages. The seventh and final voyage began in 1430, sent by the Xuande Emperor. Although the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors did not emphasize sailing as much as the Yongle Emperor, they were not against it. This led to a high degree of commercialization and an increase in trade. Large numbers of ships were built to meet the demand.

The Ming voyages were large in size, numbering as many as 300 ships and 28,000 men. The shipbuilders were brought from different places in China to the shipyard in Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

, including Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by ...

, Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north into h ...

, Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its c ...

, and Huguang (now the provinces of Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The pr ...

and Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi ...

). One of the most famous shipyards was Long Jiang Shipyard ( :zh:龙江船厂), located in Nanjing near the Treasure Shipyard where the ocean-going ships were built. The shipbuilders could built 24 models of ships of varying sizes.

keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in B ...

that determined the shape and the structure of the hull of ''Fuchuan'' Ships. The keel is the middle of the bottom of the hull, constructed by connecting three sections; stern keel, main keel and poop keel. The hull spreads in the arc towards both sides forming the keel.

* The helm

Helm may refer to:

Common meanings

* a ship's steering mechanism; see tiller and ship's wheel

* another term for helmsman

* an archaic term for a helmet, used as armor

Arts and entertainment

* Matt Helm, a character created by Donald Hamilt ...

was the device that controls direction when sailing. It was a critical invention in shipbuilding technique in ancient China and was only used by the Chinese for a fairly long time. With a developing recognition of its function, the shape and configuration of the helm was continually improved by shipbuilders. The shipbuilders not only needed to build the ship according to design, but needed to acquire the skills to improve the ships.

After 1477, the Ming government reversed its open maritime policies, enacting a series of isolationist policies in response to piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. The policies, called '' Haijin'' (sea ban), lasted until the end of the Ming dynasty in 1644. During this period, Chinese navigation technology did not make any progress and even declined in some aspect.

Indian Ocean

In the Islamic world, shipbuilding thrived atBasra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

. The dhow

Dhow ( ar, داو, translit=dāwa; mr, script=Latn, dāw) is the generic name of a number of traditional sailing vessels with one or more masts with settee or sometimes lateen sails, used in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region. Typically sp ...

, felucca, baghlah

A baghlah, bagala, bugala or baggala ( ar, بغلة) is a large deep-sea dhow, a traditional Arabic sailing vessel. The name "baghla" means "mule" in the Arabic language.

Description

The baghlah dhows had a curved prow with a stem-head, an orna ...

, and the sambuk became symbols of successful maritime trade around the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

from the ports of East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the histori ...

to Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

and the ports of Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

and Hind (India) during the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

period.

Early modern

Bengal

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the ...

had a large shipbuilding industry, which was largely centred in the Bengal Subah. Economic historian Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771. He also assesses ship repairing as very advanced in Bengal.

Shipbuilding in Bengal was advanced compared to European shipbuilding at the time, with Bengal selling ships to European firms. An important innovation in shipbuilding was the introduction of a flushed deck design in Bengal rice ships, resulting in hulls that were stronger and less prone to leak than the structurally weak hulls of traditional European ships built with a stepped deck design. The British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

later duplicated the flushed deck and hull designs of Bengal rice ships in the 1760s, leading to significant improvements in seaworthiness and navigation for European ships during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

.

West Africa

Documents from 1506, for example, refer towatercraft

Any vehicle used in or on water as well as underwater, including boats, ships, hovercraft and submarines, is a watercraft, also known as a water vessel or waterborne vessel. A watercraft usually has a propulsive capability (whether by sail ...

on the Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

river carrying 120 men. Others refer to Guinea coast

Guinea is a traditional name for the region of the African coast of West Africa which lies along the Gulf of Guinea. It is a naturally moist tropical forest or savanna that stretches along the coast and borders the Sahel belt in the north.

Et ...

peoples using war canoes of varying sizes – some 70 feet in length, 7–8 feet broad, with sharp pointed ends, rowing benches on the side, and quarterdecks or forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " b ...

s build of reeds. The watercraft included miscellaneous facilities, such as cooking hearths, and storage spaces for the crew's sleeping mats.

From the 17th century, some kingdoms added brass or iron cannons to their vessels. By the 18th century, however, the use of swivel cannons on war canoes accelerated. The city-state of Lagos

Lagos ( Nigerian English: ; ) is the largest city in Nigeria and the second most populous city in Africa, with a population of 15.4 million as of 2015 within the city proper. Lagos was the national capital of Nigeria until December 1991 f ...

, for instance, deployed war canoes armed with swivel cannons.

Europe

With the development of thecarrack

A carrack (; ; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal. Evolved from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for European trade ...

, the west moved into a new era of ship construction by building the first regular oceangoing vessels. In a relatively short time, these ships grew to an unprecedented size, complexity, and cost.

Shipyards became large industrial complexes, and the ships built were financed by consortia of investors. These considerations led to the documentation of design and construction practices in what had previously been a secretive trade run by master shipwrights and ultimately led to the field of naval architecture, in which professional designers and draftsmen played an increasingly important role. Even so, construction techniques changed only very gradually. The ships of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

were still built more or less to the same basic plan as those of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an a ...

of two centuries earlier, although there had been numerous subtle improvements in ship design and construction throughout this period. For instance, the introduction of tumblehome, adjustments to the shapes of sails and hulls, the introduction of the wheel, the introduction of hardened copper fastenings below the waterline, the introduction of copper sheathing as a deterrent to shipworm and fouling, etc.

Industrial Revolution

Though still largely based on pre-industrial era materials and designs, ships greatly improved during the early

Though still largely based on pre-industrial era materials and designs, ships greatly improved during the early Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

period (1760 to 1825), as "the risk of being wrecked for Atlantic shipping fell by one-third, and of foundering by two thirds, reflecting improvements in seaworthiness and navigation respectively." The improvements in seaworthiness have been credited to "replacing the traditional stepped deck ship with stronger flushed decked ones derived from Indian designs, and the increasing use of iron reinforcement." The design originated from Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

rice ships, with Bengal being famous for its shipbuilding industry at the time. Iron was gradually adopted in ship construction, initially to provide stronger joints in a wooden hull e.g. as deck knees, hanging knees, knee riders and the other sharp joints, ones in which a curved, progressive joint could not be achieved. One study finds that there were considerable improvements in ship speed from 1750 to 1850: "we find that average sailing speeds of British ships in moderate to strong winds rose by nearly a third. Driving this steady progress seems to be the continuous evolution of sails and rigging, and improved hulls that allowed a greater area of sail to be set safely in a given wind. By contrast, looking at every voyage between the Netherlands and East Indies undertaken by the Dutch East India Company from 1595 to 1795, we find that journey time fell only by 10 percent, with no improvement in the heavy mortality, averaging six percent per voyage, of those aboard."

Initially copying wooden construction traditions with a frame over which the hull was fastened, Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

's of 1843 was the first radical new design, being built entirely of wrought iron. Despite her success, and the great savings in cost and space provided by the iron hull, compared to a copper-sheathed counterpart, there remained problems with fouling due to the adherence of weeds and barnacles. As a result, composite construction remained the dominant approach where fast ships were required, with wooden timbers laid over an iron frame ('' Cutty Sark'' is a famous example). Later ''Great Britain''s iron hull was sheathed in wood to enable it to carry a copper-based sheathing. Brunel's represented the next great development in shipbuilding. Built-in association with John Scott Russell, it used longitudinal stringers for strength, inner and outer hulls, and bulkheads to form multiple watertight compartments. Steel also supplanted wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

when it became readily available in the latter half of the 19th century, providing great savings when compared with iron in cost and weight. Wood continued to be favored for the decks.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the need for cargo ships was so great that construction time for Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost constr ...

s went from initially eight months or longer, down to weeks or even days. They employed production line and prefabrication techniques such as those used in shipyards today. The total number of dry-cargo ships built in the United States in a 15-year period just before the war was a grand total of two. During the war, thousands of Liberty ships and Victory shipss were built, many of them in shipyards that didn't exist before the war. And, they were built by a workforce consisting largely of women and other inexperienced workers who had never seen a ship before (or even the ocean).

Worldwide shipbuilding industry

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, shipbuilding (which encompasses the shipyards, the marine equipment manufacturers, and many related service

Service may refer to:

Activities

* Administrative service, a required part of the workload of university faculty

* Civil service, the body of employees of a government

* Community service, volunteer service for the benefit of a community or a pu ...

and knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is disti ...

providers) grew as an important and strategic industry in a number of countries around the world. This importance stems from:

* The large number of skilled workers required directly by the shipyard, along with supporting industries such as steel mills

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-finished ...

, railroads and engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power ...

manufacturers; and

* A nation's need to manufacture and repair its own navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

and vessels that support its primary industries

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial secto ...

Historically, the industry has suffered from the absence of global rules and a tendency towards (state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* '' Our ...

- supported) over-investment due to the fact that shipyards offer a wide range of technologies, employ a significant number of workers, and generate income as the shipbuilding market is global

Global means of or referring to a globe and may also refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Global'' (Paul van Dyk album), 2003

* ''Global'' (Bunji Garlin album), 2007

* ''Global'' (Humanoid album), 1989

* ''Global'' (Todd Rundgren album), 2015

* Bruno ...

.

Japan used shipbuilding in the 1950s and 1960s to rebuild its industrial structure; South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

started to make shipbuilding a strategic industry in the 1970s, and China is now in the process of repeating these models with large state-supported investments in this industry. Conversely, Croatia is privatising its shipbuilding industry.

As a result, the world shipbuilding market suffers from over-capacities, depressed prices (although the industry experienced a price increase in the period 2003–2005 due to strong demand for new ships which was in excess of actual cost increases), low profit margins, trade distortions and widespread subsidisation. All efforts to address the problems in the OECD have so far failed, with the 1994 international shipbuilding agreement never entering into force and the 2003–2005 round of negotiations being paused in September 2005 after no agreement was possible. After numerous efforts to restart the negotiations these were formally terminated in December 2010. The OECD's Council Working Party on Shipbuilding (WP6) will continue its efforts to identify and progressively reduce factors that distort the shipbuilding market.

Where state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* '' Our ...

subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

have been removed and domestic industrial policies do not provide support in high labor cost countries, shipbuilding has gone into decline. The British shipbuilding industry is a prime example of this with its industries suffering badly from the 1960s. In the early 1970s British yards still had the capacity to build all types and sizes of merchant ships but today they have been reduced to a small number specialising in defence contracts, luxury yachts and repair work. Decline has also occurred in other European countries, although to some extent this has reduced by protective measures and industrial support policies. In the US, the Jones Act (which places restrictions on the ships that can be used for moving domestic cargoes) has meant that merchant shipbuilding has continued, albeit at a reduced rate, but such protection has failed to penalise shipbuilding inefficiencies. The consequence of this is that contract prices are far higher than those of any other country building oceangoing ships.

Present day shipbuilding

Beyond the 2000s, China,South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

, Japan have dominated world shipbuilding by completed gross tonnage. China State Shipbuilding Corporation, China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries

Samsung Heavy Industries Co., Ltd. ( Korean: 삼성중공업) is one of the largest shipbuilders in the world and one of the "Big Three" shipbuilders of South Korea (including Hyundai and Daewoo). Geoje (in Gyeongsangnam-do) is one of the lar ...

, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering and Imabari Shipbuilding supply most of the global market for large container, bulk carrier

A bulk carrier or bulker is a merchant ship specially designed to transport unpackaged bulk cargo — such as grains, coal, ore, steel coils, and cement — in its cargo holds. Since the first specialized bulk carrier was built in 1852, ec ...

, tanker

Tanker may refer to:

Transportation

* Tanker, a tank crewman (US)

* Tanker (ship), a ship designed to carry bulk liquids

** Chemical tanker, a type of tanker designed to transport chemicals in bulk

** Oil tanker, also known as a petroleum ta ...

and Ro-ro ships.

When referring to the type, then China, South Korea and Japan are the producing countries of the carrier ships as mentioned above. While Italy