ShinshŇękyŇć on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Japanese new religions are

Japanese new religions are

Clarke, Peter B.

(1999) ''A Bibliography of Japanese New Religious Movements: With Annotations.'' Richmond : Curzon.

OCLC 246578574

* Clarke, Peter B. (2000). ''Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective.'' Richmond : Curzon.

OCLC 442441364

* Clarke, Peter B., Somers, Jeffrey, editors (1994). Japanese New Religions in the West, Japan Library/Curzon Press, Kent, UK. * Dormann, Benjamin (2012). Celebrity Gods: New Religions, Media, and Authority in Occupied Japan, University of Hawai Ľi Press. * Dormann, Benjamin (2005). ‚

New Religions through the Eyes of ŇĆya SŇćichi, 'Emperor' of the Mass Media

ÄĚ, in: ''Bulletin of the Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture'', 29, pp. 54‚Äď67 * Dormann, Benjamin (2004). ‚

SCAP's Scapegoat? The Authorities, New Religions, and a Postwar Taboo

ÄĚ, in: ''Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'' 31/1: pp. 105‚Äď140 * Hardacre, Helen. (1988). ''Kurozumikyo and the New Religions of Japan.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Kisala, Robert (2001). ‚

Images of God in Japanese New Religions

ÄĚ, in: ''Bulletin of the Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture'', 25, pp. 19‚Äď32 * Wilson, Bryan R. and Karel Dobbelaere. (1994). ''A Time to Chant.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press. * Staemmler, Birgit, Dehn, Ulrich (ed.): Establishing the Revolutionary: An Introduction to New Religions in Japan. LIT, M√ľnster, 2011. {{DEFAULTSORT:Shinshukyo Japanese secret societies Japanese folk religion Religion in Japan East Asian religions

Japanese new religions are

Japanese new religions are new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or th ...

s established in Japan

Japan ( ja, śó•śú¨, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. In Japanese, they are called or . Japanese scholars classify all religious organizations founded since the middle of the 19th century

The 19th (nineteenth) century began on 1 January 1801 ( MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 ( MCM). The 19th century was the ninth century of the 2nd millennium.

The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolis ...

as "new religions"; thus, the term refers to a great diversity and number of organizations. Most came into being in the mid-to- late twentieth century and are influenced by much older traditional religions including Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

and Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

. Foreign influences include Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

and the writings of Nostradamus

Michel de Nostredame (December 1503 ‚Äď July 1566), usually Latinised as Nostradamus, was a French astrologer, apothecary, physician, and reputed seer, who is best known for his book ''Les Proph√©ties'' (published in 1555), a collection o ...

.

Before World War II

In the 1860s Japan began to experience great social turmoil and rapid modernization. As social conflicts emerged in this last decade of theEdo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

, known as the Bakumatsu

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government ...

period, some new religious movements appeared. Among them were Tenrikyo

is a Japanese new religion which is neither strictly monotheistic nor pantheistic, originating from the teachings of a 19th-century woman named Nakayama Miki, known to her followers as "Oyasama". Followers of Tenrikyo believe that God of Origin, ...

, Kurozumikyo and Oomoto

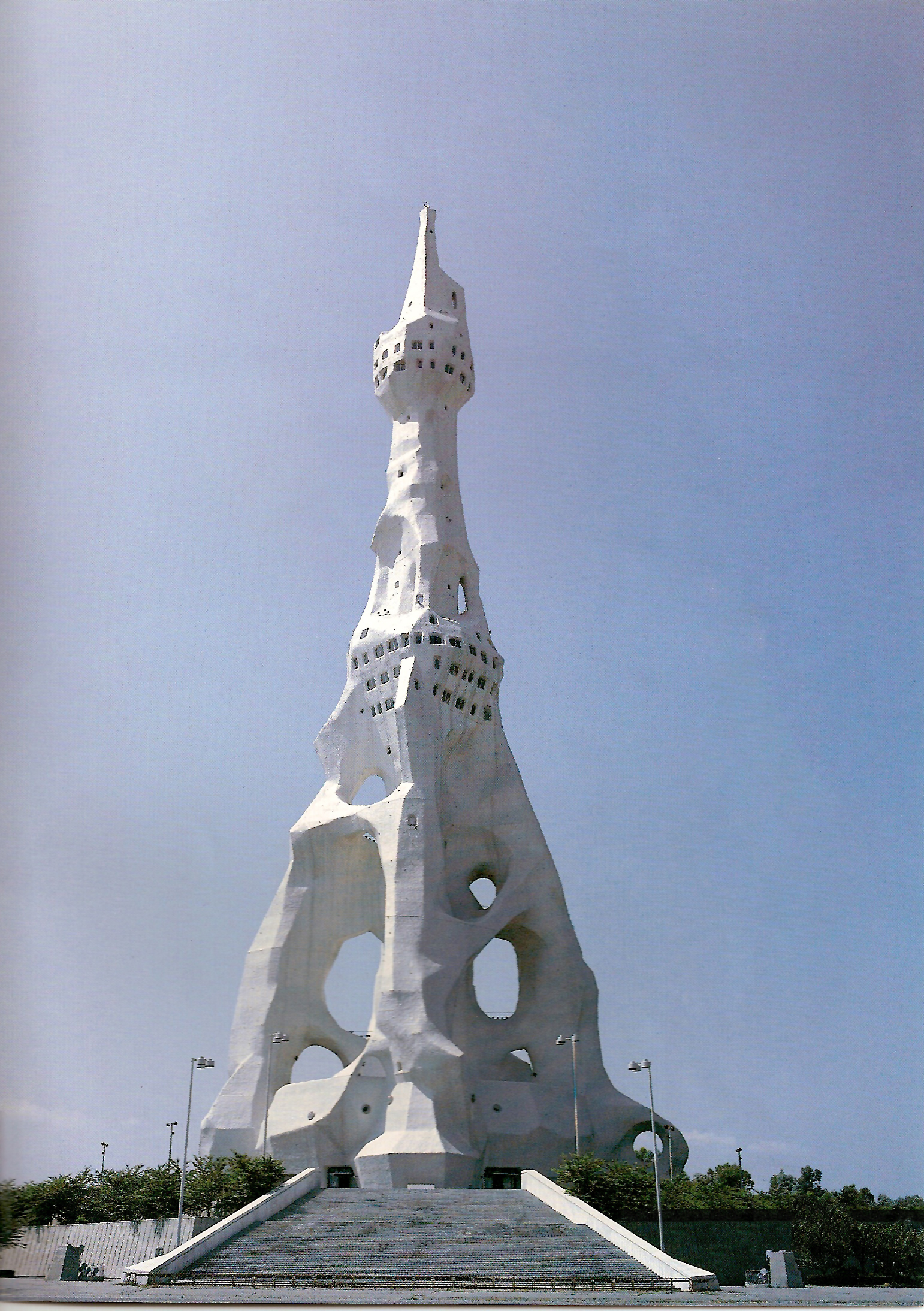

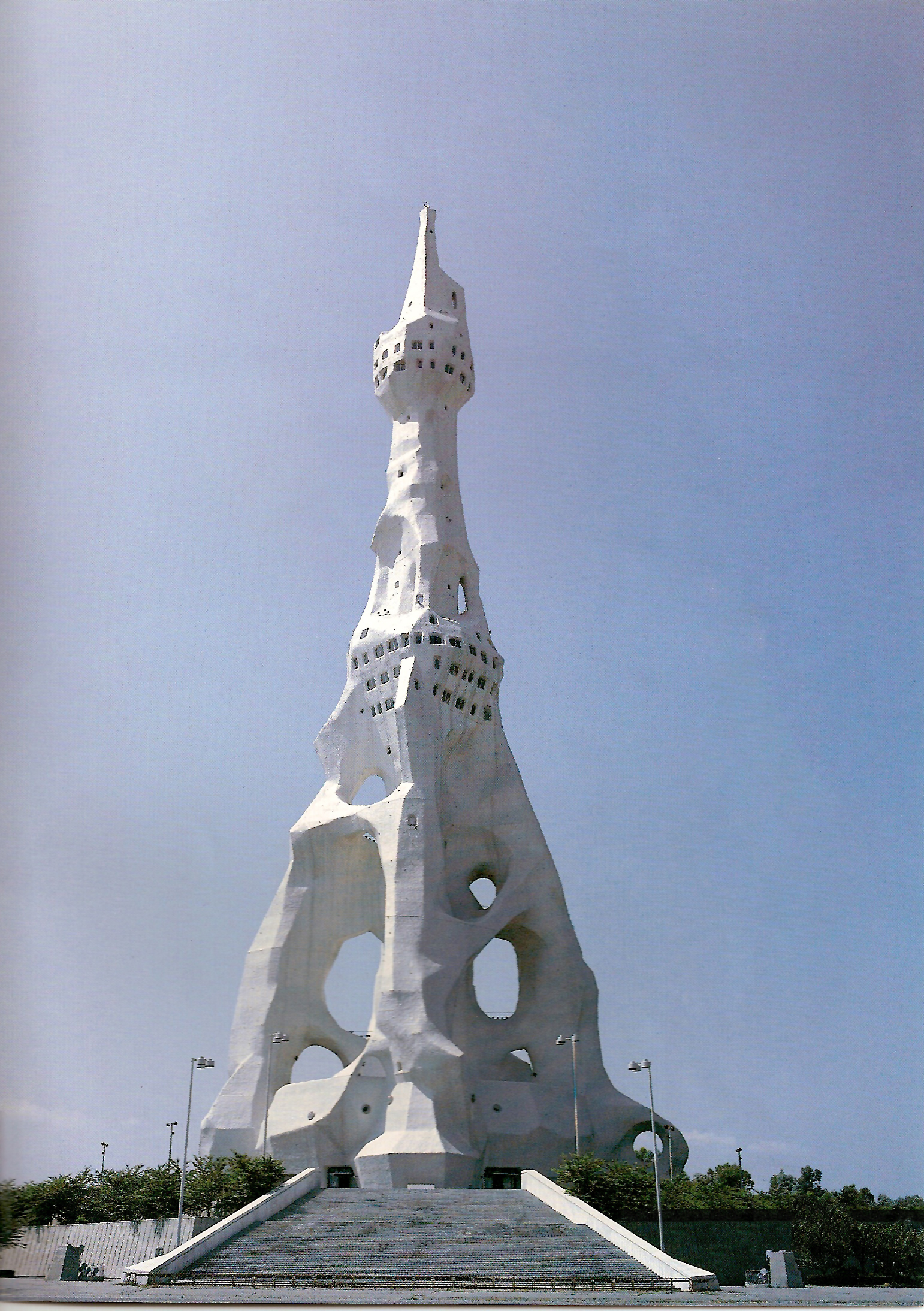

''ChŇćseiden'' in Ayabe

, also known as , is a religion founded in 1892 by Deguchi Nao (1836‚Äď1918), often categorised as a new Japanese religion originated from Shinto. The spiritual leaders of the movement have always been women within t ...

, sometimes called ''Nihon Sandai ShinkŇćshŇękyŇć'' ("Japan's three large new religions"), which were directly influenced by Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

(the state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

) and shamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a Spirit world (Spiritualism), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as tranc ...

.

The social tension continued to grow during the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

, affecting religious practices and institutions. Conversion from traditional faith was no longer legally forbidden, officials lifted the 250-year ban on Christianity, and missionaries of established Christian churches reentered Japan. The traditional syncreticism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

between Shinto and Buddhism ended and Shinto became the national religion. Losing the protection of the Japanese government which Buddhism had enjoyed for centuries, Buddhist monks faced radical difficulties in sustaining their institutions, but their activities also became less restrained by governmental policies and restrictions.

The Japanese government was very suspicious towards these religious movements and periodically made attempts to suppress them. Government suppression was especially severe during the early 20th century, particularly from the 1930s until the early 1940s, when the growth of Japanese nationalism

is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that the Japanese are a monolithic nation with a single immutable culture, and promotes the cultural unity of the Japanese. Over the last two centuries, it has encompassed a broad range of ideas a ...

and State Shinto

was Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that emphasized the Emperor as ...

were closely linked. Under the Meiji regime '' lèse majesté'' prohibited insults against the Emperor and his Imperial House, and also against some major Shinto shrines which were believed to be tied strongly to the Emperor. The government strengthened its control over religious institutions that were considered to undermine State Shinto or nationalism, arresting some members and leaders of Shinshukyo, including Onisaburo Deguchi

, born Ueda KisaburŇć šłäÁĒį ŚĖúšłČťÉé (1871–1948), is considered one of the two spiritual leaders of the ŇĆmoto religious movement in Japan.

History

Onisaburo had studied Honda Chikaatsu's "Spirit Studies" (Honda Reigaku), he also learned ...

of Oomoto and TsunesaburŇć Makiguchi

TsunesaburŇć Makiguchi (ÁČߌŹ£ ŚłłšłČťÉé, ''Makiguchi TsunesaburŇć''; 23 July 1871 (lunar calendar date 6 June) ‚Äď 18 November 1944) was a Japanese educator who founded and became the first president of the SŇćka KyŇćiku Gakkai (Value-Creating ...

of Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (now Soka Gakkai

is a Japanese Buddhist religious movement based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese priest Nichiren as taught by its first three presidents TsunesaburŇć Makiguchi, JŇćsei Toda, and Daisaku Ikeda. It is the largest of the Japanese ...

), who typically were charged with violation of ''lèse majesté'' and the Peace Preservation Law

The was a Japanese law enacted on April 22, 1925, with the aim of allowing the Special Higher Police to more effectively suppress socialists and communists. In addition to criminalizing forming an association with the aim of altering the ''kokuta ...

.

After World War II

Background

After Japan lost World War II, its government and policy changed radically duringoccupation

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

by Allied troops. The official status of State Shinto

was Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that emphasized the Emperor as ...

was abolished, and Shinto shrines became religious organizations, losing government protection and financial support. Although the Occupation Army (GHQ) practiced censorship of all types of organizations, specific suppression of ShinshŇękyŇć ended.

GHQ invited many Christian missionaries from the United States to Japan, through Douglas MacArthur's famous call for 1,000 missionaries. Missionaries arrived not only from traditional churches, but also from some modern denominations, such as Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

. The Jehovah's Witnesses missionaries were so successful that they have become the second largest Christian denomination in Japan, with over 210,000 members (the largest is Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

with about 500,000 members). In Japan, Jehovah's Witnesses tend to be considered a Christianity-based ShinshŇękyŇć, not only because they were founded in the 19th century (as were other major ShinshŇękyŇć), but also because of their missionary practices, which involve door-to-door visiting and frequent meetings.

Despite the influx of Christian missionaries, the majority of ShinshŇękyŇć are Buddhist- or Shinto-related sects. Major sects include RisshŇć KŇćsei Kai

; until June 1960, is a Japanese new religious movement founded in 1938 by NikkyŇć Niwano and MyŇćkŇć Naganuma. RisshŇć KŇćsei Kai is organized as a lay Buddhist movement, which branched off from the older ReiyŇękai, and is primarily focused a ...

and Shinnyo-en

is a Japanese Buddhist new religious movement in the tradition of the Daigo branch of Shingon Buddhism. It was founded in 1936 by , and his wife in a suburb of metropolitan Tokyo, the city of Tachikawa, where its headquarters is still located. ...

. Major goals of ShinshŇękyŇć include spiritual healing, individual prosperity, and social harmony. Many also hold a belief in Apocalypticism

Apocalypticism is the religious belief that the Eschatology, end of the world is imminent, even within one's own lifetime. This belief is usually accompanied by the idea that civilization will soon come to a tumultuous end due to some sort of c ...

, that is in the imminent end of the world or at least its radical transformation.Peter B. Clarke

Peter Bernard Clarke (25 October 1940 ‚Äď 24 June 2011) was a British scholar of religion and founding editor of the ''Journal of Contemporary Religion''.Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

Most of those who joined ShinshŇękyŇć in this period were women from lower-middle-class backgrounds.Eileen Barker

Eileen Vartan Barker (born 21 April 1938, in Edinburgh, UK) is a professor in sociology, an emeritus member of the London School of Economics (LSE), and a consultant to that institution's Centre for the Study of Human Rights. She is the chairpe ...

, 1999, "New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance", ''New Religious Movements: challenge and response'', Bryan Wilson and Jamie Cresswell editors, Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

Soka Gakkai

is a Japanese Buddhist religious movement based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese priest Nichiren as taught by its first three presidents TsunesaburŇć Makiguchi, JŇćsei Toda, and Daisaku Ikeda. It is the largest of the Japanese ...

has a particular influence to politics since 1964, thanks to their affiliated party Komeito, later New Komeito

, formerly New Komeito and abbreviated NKP, is a conservative political party in Japan founded by lay members of the Buddhist Japanese new religions, Japanese new religious movement Soka Gakkai in 1964. Since 2012, it has served in government ...

. In 1999, it was estimated that 10 to 20 per cent of the Japanese population were members of a ShinshŇękyŇć.

Influence

After World War II, the structure of the state was changed radically. Prior to WWII, theNational Diet

The is the national legislature of Japan. It is composed of a lower house, called the House of Representatives (Japan), House of Representatives (, ''ShŇęgiin''), and an upper house, the House of Councillors (Japan), House of Councillors (, ...

was restricted and the real power lay with the executive branch, in which the prime minister was appointed by the emperor. Under the new Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan (Shinjitai: , KyŇęjitai: , Hepburn: ) is the constitution of Japan and the supreme law in the state. Written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japan, the constitution r ...

, the Diet had the supreme authority for decision making in state affairs and all its members were elected by the people. Especially in the House of Councillors

The is the upper house of the National Diet of Japan. The House of Representatives is the lower house. The House of Councillors is the successor to the pre-war House of Peers. If the two houses disagree on matters of the budget, treaties, ...

, one third of whose members were elected through nationwide vote, nationwide organizations found they could influence national policy by supporting certain candidates. Major ShinshŇękyŇć became one of the so-called "vote-gathering machines" in Japan, especially for the conservative parties which merged into the Liberal Democratic Party in 1955.

Other nations

In the 1950s, Japanese wives of American servicemen introduced the Soka Gakkai to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, which in the 1970s developed into the Soka Gakkai International

Soka Gakkai International (SGI) is an international Nichiren Buddhist organisation founded in 1975 by Daisaku Ikeda, as an umbrella organization of Soka Gakkai, which declares approximately 12 million adherents in 192 countries and territories ...

(SGI). The SGI has steadily gained members while avoiding much of the controversy encountered by some other new religious movements in the US. Well-known American SGI converts include musician Herbie Hancock

Herbert Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is an American jazz pianist, keyboardist, bandleader, and composer. Hancock started his career with trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. He shortly thereafter joined the Miles Davis Quintet, where he help ...

and singer Tina Turner

Tina Turner (born Anna Mae Bullock; November 26, 1939) is an American-born Swiss retired singer and actress. Widely referred to as the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Queen of Rock 'n' Roll", she rose to prominence as the lead singer o ...

.Eugene V. Gallagher, 2004, ''The New Religious Movement Experience in America'', Greenwood Press

Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. (GPG), also known as ABC-Clio/Greenwood (stylized ABC-CLIO/Greenwood), is an educational and academic publisher (middle school through university level) which is today part of ABC-Clio. Established in 1967 as Gr ...

, , pages 120‚Äď124

In Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

ShinshŇękyŇć, like Honmon ButsuryŇę-shŇę

The Honmon ButsuryŇę-shŇę () is a branch of the Honmon Hokke ShŇę sect (one of the most ancient sects of Nichiren Buddhism). It was founded by Nagamatsu Nissen (; 1817‚Äď1890) and a group of followers the 12th of January 1857 with the name of Ho ...

, were first introduced in the 1920s among the Japanese immigrant population. In the 1950s and 1960s some started to become popular among the non-Japanese population as well. Seicho-no-Ie now has the largest membership in the country. In the 1960s it adopted Portuguese, rather than Japanese, as its language of instruction and communication. It also began to advertise itself as philosophy rather than religion in order to avoid conflict with the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and other socially conservative elements in society. By 1988 it had more than 2.4 million members in Brazil, 85% of them not of Japanese ethnicity.

Statistics

Data for 2012 is from theAgency for Cultural Affairs

The is a special body of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). It was set up in 1968 to promote Japanese arts and culture.

The agency's budget for FY 2018 rose to ¥107.7 billion.

Overview

The ag ...

.

See also

*Buddhism in Japan

Buddhism has been practiced in Japan since about the 6th century CE. Japanese Buddhism () created many new Buddhist schools, and some schools are original to Japan and some are derived from Chinese Buddhist schools. Japanese Buddhism has had a ...

*Buddhist modernism

Buddhist modernism (also referred to as modern Buddhism, modernist Buddhism, and Neo-Buddhism are new movements based on modern era reinterpretations of Buddhism. David McMahan states that modernism in Buddhism is similar to those found in other ...

*Religion in Japan

Religion in Japan is manifested primarily in Shinto and in Buddhism, the two main faiths, which Japanese people often practice simultaneously. According to estimates, as many as 80% of the populace follow Shinto rituals to some degree, worshipi ...

*Shinto sects and schools

, the folk religion of Japan, developed a diversity of schools and sects, outbranching from the original Ko-ShintŇć (ancient ShintŇć) since Buddhism was introduced into Japan in the sixth century.

Early period schools and groups

The main Shinto s ...

(only some on the list count as Shinshukyo)

References

Bibliography

Clarke, Peter B.

(1999) ''A Bibliography of Japanese New Religious Movements: With Annotations.'' Richmond : Curzon.

OCLC 246578574

* Clarke, Peter B. (2000). ''Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective.'' Richmond : Curzon.

OCLC 442441364

* Clarke, Peter B., Somers, Jeffrey, editors (1994). Japanese New Religions in the West, Japan Library/Curzon Press, Kent, UK. * Dormann, Benjamin (2012). Celebrity Gods: New Religions, Media, and Authority in Occupied Japan, University of Hawai Ľi Press. * Dormann, Benjamin (2005). ‚

New Religions through the Eyes of ŇĆya SŇćichi, 'Emperor' of the Mass Media

ÄĚ, in: ''Bulletin of the Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture'', 29, pp. 54‚Äď67 * Dormann, Benjamin (2004). ‚

SCAP's Scapegoat? The Authorities, New Religions, and a Postwar Taboo

ÄĚ, in: ''Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'' 31/1: pp. 105‚Äď140 * Hardacre, Helen. (1988). ''Kurozumikyo and the New Religions of Japan.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Kisala, Robert (2001). ‚

Images of God in Japanese New Religions

ÄĚ, in: ''Bulletin of the Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture'', 25, pp. 19‚Äď32 * Wilson, Bryan R. and Karel Dobbelaere. (1994). ''A Time to Chant.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press. * Staemmler, Birgit, Dehn, Ulrich (ed.): Establishing the Revolutionary: An Introduction to New Religions in Japan. LIT, M√ľnster, 2011. {{DEFAULTSORT:Shinshukyo Japanese secret societies Japanese folk religion Religion in Japan East Asian religions