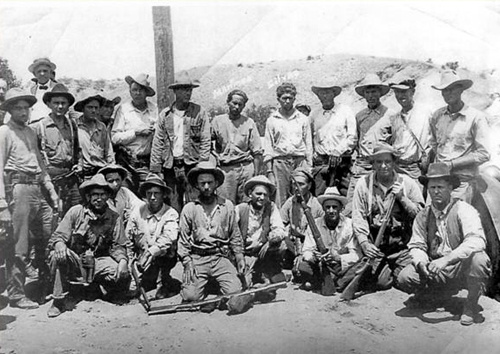

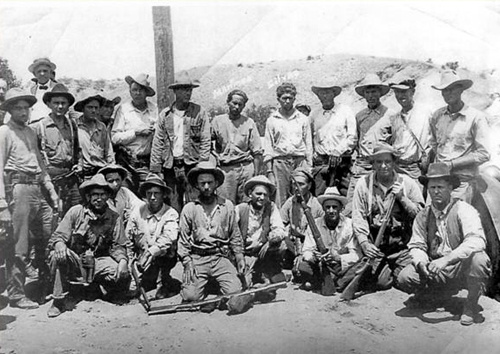

sheriff's posse on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''posse comitatus'' (from

The ''posse comitatus'' (from

/ref> This subsection is still in force. This power can be used during the execution of a writ of seizure and sale to satisfy a debt; it allows a sheriff to call upon the police while seizing the property.

The ''posse comitatus'' (from

The ''posse comitatus'' (from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for "the ability to have a retinue or gang"), frequently shortened to posse, is in common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

a group of people mobilized to suppress lawlessness, defend the people, or otherwise protect the place, property, and public welfare. It may be called by the conservator of peace – typically a reeve, sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland, the , which is common ...

, chief, or another special/regional designee like an officer of the peace potentially accompanied by or with the direction of a justice or ajudged parajudicial process given the imminence of actual damage. There must be a lawful reason for a posse, which can never be used for lawlessness. The ''posse comitatus'' as an English jurisprudentially defined doctrine dates back to 9th-century England.

Etymology

Derived fromLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, ''posse comitātūs'' ("posse" here used as a noun means the ability or power while "comittus" is an abstract noun which means a retinue, especially a small military force or bodyguard) is sometimes shortened to simply ''posse'' from the mid-17th century onward to describe the force itself more than the legal principle. While the original meaning refers to a group of citizens assembled by the authorities to deal with an emergency (such as suppressing a riot or pursuing felons and outlawry), the term is also used for any force or band, especially with hostile intent, often also figuratively or humorously. In 19th-century usage, ''posse comitatus'' also acquired the generalized or figurative meaning. In its earliest days, the ''posse comitatus'' was subordinate to the king, country, and local authority.

United Kingdom

Middle Ages

The ''posse comitatus'' as an English jurisprudentially defined doctrine dates back to 9th-century England and the campaigns ofAlfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

, and before in ancient custom and law of locally martialed forces, simultaneous thereafter with the officiation of sheriff nomination to keep the regnant peace (known as " the Queen/king's peace").

English Civil War

In 1642, during the early stages of theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, local forces were employed everywhere and by both sides. The powers responsible produced valid written authority, inducing the locals to assemble. The two most common authorities used were the Militia Ordinance on the side of the Parliamentarians and that of the king, the old-fashioned Commissions of Array. But the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

leader in Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, Sir Ralph Hopton, indicted the enemy before the grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

of the county as disturbers of the peace, and had the ''posse comitatus'' called out to expel them.

In law

The powers of sheriffs in England and Wales for ''posse comitatus'' were codified by section 8 of the Sheriffs Act 1887, the first subsection of which stated that: This permitted thesheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland, the , which is common ...

of each county to call every civilian to his assistance to catch a person who had committed a felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that r ...

– that is, a serious crime. It provided for fines for those who did not comply. The provisions for ''posse comitatus'' were repealed by the Criminal Law Act 1967

The Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that made some major changes to English criminal law, as part of wider liberal reforms by the Labour government elected in 1966. Most of it is still in force. ...

. The second subsection provided for the sheriff to take "the power of the county" if he faced resistance while executing a writ

In common law, a writ is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrant (legal), Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, and ''certiorari'' are commo ...

, and provided for the arrest of resisters.section 8, Sheriffs Act 1887 (as passed)/ref> This subsection is still in force. This power can be used during the execution of a writ of seizure and sale to satisfy a debt; it allows a sheriff to call upon the police while seizing the property.

United States

The ''posse comitatus'' power continues to exist in those common-lawstates

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

that have not expressly repealed it by statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

. As an example, it is codified in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

under OCGA 17-4-24:

In some states, especially in the western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau.

As American settlement i ...

, sheriffs and other law enforcement agencies have called their civilian auxiliary groups "posses". The Lattimer Massacre of 1897 illustrated the danger of such groups and thus ended their use in situations of civil unrest

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, civil strife, or turmoil, are situations when law enforcement and security forces struggle to maintain public order or tranquility.

Causes

Any number of things may cause civil di ...

. ''Posse comitatus'' in the US became not an instrument of royal prerogative but an institution of local self-governance. The posse functioned through, rather than upon, the local popular will. From 1850 to 1878, the United States federal government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

had expanded its power over individuals. This was done to safeguard national property rights for slaveholders, emancipate millions of enslaved African Americans, and enforce the doctrine of formal equality. The rise of the federal state, like the marketplace before it, had created contradictory but congruous forces of liberation and compulsion upon individuals.

In the early decades of the United States, before slavery became a major conflict, federal use of ''posse comitatus'' in the states was rare. But the federal ''posse comitatus'', quite literally, had compelled all of the United States to accept the legitimacy of slavery. In an exhaustive study of lynching in Colorado, historian Stephen Leonard defines lynching to include the people's courts and even posses, which by definition were led by sheriffs."Lynching in Colorado, 1859–1919" (University Press Colorado, 2002).

In the United States, a federal statute known as the Posse Comitatus Act

The Posse Comitatus Act is a United States federal law (, original at ) signed on June 18, 1878, by President Rutherford B. Hayes that limits the powers of the federal government in the use of federal military personnel to enforce domestic pol ...

, enacted in 1878, forbids the use of the US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

(and, as amended, the US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

, Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

, Marine Corps

Marines (or naval infantry) are military personnel generally trained to operate on both land and sea, with a particular focus on amphibious warfare. Historically, the main tasks undertaken by marines have included raiding ashore (often in supp ...

, and Space Force

A space force is a military branch of a nation's armed forces that conducts military operations in outer space and space warfare. The world's first space force was the Russian Space Forces, established in 1992 as an independent military service. ...

), as a ''posse comitatus'' or for law enforcement purposes without the approval of Congress. The act originally did not mention branches of the military other than the Army (and subsequently the Air Force after its establishment), leading the US Department of the Navy and the US Secretary of Defense

The United States secretary of defense (acronym: SecDef) is the head of the United States Department of Defense (DoD), the executive department of the U.S. Armed Forces, and is a high-ranking member of the federal cabinet. DoDD 5100.1: Enclos ...

to prescribe equivalent regulations prohibiting the use of other branches for domestic law enforcement. In 2021, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 (; NDAA 2022Pub.L. 117-81 is a United States federal law which specifies the budget, expenditures and policies of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) for fiscal year 2022. Analogous N ...

amended the Act to formally apply the same restrictions to the domestic use of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Space Force. The limitation does not apply to the National Guard of the United States

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

when activated by a state's governor and operating under Title 32 of the US Code, such as deployments by state governors in response to Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a powerful, devastating and historic tropical cyclone that caused 1,392 fatalities and damages estimated at $125 billion in late August 2005, particularly in the city of New Orleans and its surrounding area. ...

.

Notable posses

In response to the dispatch of militia by the governor ofWashington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represe ...

, to arrest Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territory's supreme court, who was holding court in the Pierce County Courthouse, the sheriff of Pierce County deputized 50 to 60 civilians for the defense of the court. Negotiations ultimately resolved the standoff; the militia withdrew.

In 1897 the sheriff of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania

Luzerne County is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of , of which is land and is water. It is Northeaste ...

, deputized 100 civilians to supplement 50 deputy sheriffs in confronting 400 striking mine workers at the Lattimer Mines. The posse fired at the strikers, killing 19 workers in what became known as the Lattimer massacre.

In 1994, violent bank robbers fled from Mineral County, Colorado

Mineral County is a county located in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 census, the population was 865, making it the third-least populous county in Colorado, behind San Juan County and Hinsdale County. The county seat and only ...

, into remote Hinsdale County, Colorado

Hinsdale County is a county located in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 788, making it the second least-populous county in Colorado. With a population density of only , it is also ...

, which at the time had two law enforcement officers for its 500 residents. The county sheriff summoned the county's power, directing more than 100 deputized civilians and 200 out-of-town police officers in house-to-house searches for the fugitives. The robbers committed suicide as the posse closed in on their location.

Legal status

Following theBaltimore riot of 1968

The Baltimore riot of 1968 was a period of civil unrest that lasted from April 6 to April 14, 1968, in Baltimore. The uprising included crowds filling the streets, burning and looting local businesses, and confronting the police and national gua ...

, 1,500 lawsuits were filed against the city of Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

seeking compensation for damages sustained due to the failure of the police to suppress the unrest. The city sought declaratory judgment arguing that it could not be liable for any failures of the Baltimore municipal police, as it was an agency of the State of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

and the city had no law enforcement authority. In rejecting the argument, the Maryland Court of Appeals observed that Baltimore, as an independent city

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

and – therefore – a county equivalent, was still in possession of the ability to summon the power of the county as that right had not explicitly been repealed by statute and, therefore, remained part of the common law. The court noted:

In the ''Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology'', David Kopel observed that almost all US states provide statutory authority for sheriffs, or other local officials, to summon the county's power. In many cases, civil and criminal penalties are prescribed for members of the public who shirk posse duty when summoned; South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

provides that "any person refusing to assist as one of the posse ... shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and, upon conviction shall be fined not less than thirty nor more than one hundred dollars or imprisoned for thirty days" while in New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

a fine of "not more than $20" has been set.

Title 42, section 1989, of the United States Code

The United States Code (formally The Code of Laws of the United States of America) is the official Codification (law), codification of the general and permanent Law of the United States#Federal law, federal statutes of the United States. It ...

extends the authority to summon the power of the county to United States magistrate judge

In United States federal courts, magistrate judges are judges appointed to assist U.S. district court judges in the performance of their duties. Magistrate judges generally oversee first appearances of criminal defendants, set bail, and conduct ...

s when necessary to enforce their orders:

See also

* Commandeering *Conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

* Hue and cry

In common law, a hue and cry is a process by which bystanders are summoned to assist in the apprehension of a criminal who has been witnessed in the act of committing a crime.

History

By the Statute of Winchester of 1285, 13 Edw. 1. St. 2. c. ...

* Ku Klux Klan raid (Inglewood)

* Misprision

The term ''misprision'' (from , modern , "to misunderstand") in English law describes certain kinds of offence. Writers on criminal law usually divide misprision into two kinds: negative and positive.

It survives in the law of England and Wales an ...

* Vigilantism in the United States of America

References

External links

*{{Wiktionary-inline, posse comitatus Common law Legal history Latin legal terminology History of criminal justice