Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the  Uncertainty surrounds the fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the first Spanish explorers in the 16th century. After 1525 at Madisonville, the

Uncertainty surrounds the fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the first Spanish explorers in the 16th century. After 1525 at Madisonville, the

New York: Putnam's sons, 1911, esp. chap. IV, "The Shawnees", pp. 119–160. Based on historical accounts and later archeology, John E. Kleber describes Shawnee towns by the following:

Prior to 1754, the Shawnee had a headquarters at Shawnee Springs at modern-day

in JSTOR

/ref> War leaders such as

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee leader

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee leader

In March the

In March the

The Muscogee (Creek) who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the

The Muscogee (Creek) who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the

File:Eastern shawnee flag.jpg, Flag of the

Kakowatchiky

/ref> * Kekewepelethy (Captain Johnny, d. c. 1808), principal civil chief of the Shawnees in the Ohio Country during the Northwest Indian War * Captain Logan (Spemica Lawba, "High Horn," c. 1776–1812), noted scout and interpreter on American side during the

Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

official website

Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

official website

Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

official website

Access Genealogy

Central Michigan State University

BlueJacket

{{authority control Shawnee tribe, Algonquian ethnonyms Native American tribes in Indiana Native American tribes in Kentucky Native American tribes in Missouri Native American tribes in Ohio Native American tribes in Oklahoma Native American tribes in Pennsylvania Native American tribes in Virginia Native American tribes in Alabama Native American tribes in Kansas Native Americans in the American Revolution Prehistoric cultures in Ohio

indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada. It is part ...

. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, with some bands in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. By the 19th century, they were forcibly removed to Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, and ultimately Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

, which became Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

under the 1830 Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

.

Today, Shawnee people are enrolled in three federally recognized tribes

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

, all headquartered in Oklahoma: the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians

The Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma (or Absentee Shawnee) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Shawnee people. Historically residing in what became organized as the upper part of the Eastern United States, the original ...

, Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

The Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma is one of three federally recognized Shawnee tribes. They are located in Oklahoma and Missouri.

The tribe holds an annual powwow every September at their tribal complex.

Government

The headquarters of the Ea ...

, and Shawnee Tribe

The Shawnee Tribe is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma. Formerly known as the Loyal Shawnee, they are one of three federally recognized Shawnee tribes. The others are the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma and th ...

.

Etymology

Shawnee has also been written as Shaawanwaki, Ša·wano·ki, Shaawanowi lenaweeki, and Shawano. Algonquian languages have words similar to the archaic ''shawano'' (now: ''shaawanwa'') meaning "south". However, the stem ''šawa-'' does not mean "south" in Shawnee, but "moderate, warm (of weather)": SeeCharles F. Voegelin

Charles Frederick "Carl" Voegelin (January 14, 1906 – May 22, 1986), often cited as C. F. Voegelin, was an American linguist and anthropologist. He was one of the leading authorities on Indigenous languages of North America, specifically the Al ...

, "šawa (plus -ni, -te) MODERATE, WARM. Cp. šawani 'it is moderating...". In one Shawnee tale, "Sawage" (šaawaki) is the deity of the south wind. Jeremiah Curtin translates Sawage as 'it thaws', referring to the warm weather of the south. In an account and a song collected by C. F. Voegelin, šaawaki is attested as the spirit of the South, or the South Wind.

Language

In 2002, theShawnee language

The Shawnee language is a Central Algonquian language spoken in parts of central and northeastern Oklahoma by the Shawnee people. It was originally spoken by these people in a broad territory throughout the Eastern United States, mostly north of ...

, from the Algonquian family, was in decline, spoken by only 200 people. These included more than 100 Absentee Shawnee and 12 Shawnee Tribe speakers. The language is written in the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern Italy ...

. It has a dictionary, and portions of the Bible have been translated into Shawnee.

History

Precontact history

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the precontact

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the Migration to the New World, original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization of the Americas, European colonization, w ...

Fort Ancient

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from Ca. 1000-1750 CE and predominantly inhabited land near the Ohio River valley in the areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana and western ...

culture of the Ohio region, although this is not universally accepted. The Shawnee may have entered the area at a later time and occupied the Fort Ancient sites.

Fort Ancient culture flourished from c. 1000 to c. 1750 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited lands on both sides of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

in areas of present-day southern Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, northern Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and western West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

. Like the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

peoples of this period, they built earthwork mounds as part of their expression of their religious and political structure. Fort Ancient culture was once thought to have been a regional extension of the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

. Scholars now believe that Fort Ancient culture developed independently and was descended from the Hopewell culture

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from ...

(100 BCE—500 CE). The people in those earlier centuries also built mounds as part of their social, political and religious system. Among their monuments were earthwork effigy mound

An effigy mound is a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, religious figure, human, or other figure. The Effigy Moundbuilder culture is primarily associated with the years 550-1200 CE during the Late Woodland Peri ...

s, such as Serpent Mound

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-foot-long (411 m), three-foot-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. The mound itself resides on the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. ...

in present-day Ohio.

Uncertainty surrounds the fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the first Spanish explorers in the 16th century. After 1525 at Madisonville, the

Uncertainty surrounds the fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the first Spanish explorers in the 16th century. After 1525 at Madisonville, the type site

In archaeology, a type site is the site used to define a particular archaeological culture or other typological unit, which is often named after it. For example, discoveries at La Tène and Hallstatt led scholars to divide the European Iron Age ...

, the village's house sizes became smaller and fewer. Evidence shows that the people changed from their previously "horticulture-centered, sedentary way of life".

There is a gap in the archaeological record between the most recent Fort Ancient sites and the oldest sites of the historic Shawnee. The latter were recorded by European (French and English) archaeologists as occupying this area at the time of encounter. Scholars generally accept that similarities in material culture, art, mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

, and Shawnee oral history linking them to the Fort Ancient peoples, can be used to support the connection from Fort Ancient society and development as the historical Shawnee society. But there is also evidence and oral history linking Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the entire ...

-speaking nations to the Ohio Valley.

The Shawnee considered the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

(or Delaware) of the East Coast mid-Atlantic region, who were also Algonquian speaking, to be their "grandfathers". The Algonquian nations of present-day Canada, who extended to the interior along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

and around the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

from the Atlantic coast, regarded the Shawnee as their southernmost branch. Along the East Coast, the Algonquian-speaking tribes were historically located mostly in coastal areas, from Quebec to the Carolinas.

17th century

Europeans reported encountering the Shawnee over a wide geographic area. One of the earliest mentions of the Shawnee may be a 1614 Dutch map showing some ''Sawwanew'' located just east of theDelaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

. Later 17th-century Dutch sources also place them in this general location. Accounts by French explorers in the same century usually located the Shawnee along the Ohio River, where the French encountered them on forays from eastern Canada and the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

.Charles Augustus Hanna, ''The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Volume 1''New York: Putnam's sons, 1911, esp. chap. IV, "The Shawnees", pp. 119–160. Based on historical accounts and later archeology, John E. Kleber describes Shawnee towns by the following:

A Shawnee town might have from forty to one hundred bark-covered houses similar in construction toAccording to one English colonial legend, some Shawnee were descended from a party sent by ChiefIroquois The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...longhouses A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America. Many were built from timber and often rep .... Each village usually had a meeting house orcouncil house A council house is a form of British public housing built by local authorities. A council estate is a building complex containing a number of council houses and other amenities like schools and shops. Construction took place mainly from 1919 ..., perhaps sixty to ninety feet long, where public deliberations took place.

Opechancanough

Opechancanough (; 1554–1646)Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, ''Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown.'' University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, 2005 was paramount chief of the Tsenacommacah, Powhatan Confed ...

, ruler of the Powhatan Confederacy

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

of 1618–1644, to settle in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

. The party was led by his son, Sheewa-a-nee. Edward Bland, an explorer who accompanied Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood (1610–1682), sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader, militia officer, politician and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia. Wood helped build and maintained Fort Henry at the falls of ...

's expedition in 1650, wrote that in Opechancanough's day, there had been a falling-out between the ''Chawan'' chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

and the ''weroance'' of the Powhatan (also a relative of Opechancanough's family). He said the latter had murdered the former. The Shawnee were "driven from Kentucky in the 1670s by the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

of Pennsylvania and New York, who claimed the Ohio valley as hunting ground to supply its fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

. The colonists Batts and Fallam in 1671 reported that the Shawnee were contesting control of the Shenandoah Valley with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

) in that year, and were losing.

Some time before 1670, a group of Shawnee migrated to the Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of South Carolina and Georgia. Two tributaries of the Savannah, the Tugaloo River and the Chattooga River, form the norther ...

area. The English based in Charles Town, South Carolina, were contacted by these Shawnee in 1674. They forged a long-lasting alliance. The Savannah River Shawnee were known to the Carolina English as "Savannah Indians". Around the same time, other Shawnee groups migrated to Florida, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Pennsylvania, and other regions south and east of the Ohio country. Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

, founder of New Orleans and the French colony of La Louisiane

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

, writing in his journal in 1699, describes the Shawnee (or as he spells them, ''Chaouenons'') as "the single nation to fear, being spread out over Carolina and Virginia in the direction of the Mississippi."

Historian Alan Gallay

Alan Gallay is an American historian. He specializes in the Atlantic World and Early American history, including issues of slavery. He won the Bancroft Prize in 2003 for his ''The Indian Slave Trade: the Rise of the English Empire in the American S ...

speculates that the Shawnee migrations of the middle to late 17th century were probably driven by the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

, which began in the 1640s. Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy invaded from the east to secure the Ohio Valley for hunting grounds. The Shawnee became known for their widespread settlements, extending from Pennsylvania to Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

and to Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Among their known villages were '' Eskippakithiki'' in Kentucky, ''Sonnionto'' (also known as Lower Shawneetown

Lower Shawneetown, also known as Shannoah or Sonnontio, was an 18th-century Shawnee village located within the Lower Shawneetown Archeological District, near South Portsmouth in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky. The population ...

) in Ohio, ''Chalakagay'' near what is now Sylacauga, Alabama

Sylacauga is a city in Talladega County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 12,578.

Sylacauga is known for its fine white marble bedrock. This was discovered shortly after settlers moved into the area and has been ...

, ''Chalahgawtha

Chalahgawtha (or, more commonly in English, Chillicothe) was the name of one of the five divisions (or bands) of the Shawnee, a Native American people, during the 18th century. It was also the name of the principal village of the division. The ot ...

'' at the site of present-day Chillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Ross County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Scioto River 45 miles (72 km) south of Columbus, Chillicothe was the first and third capital of Ohio. It is the only city in Ross Count ...

, Old Shawneetown, Illinois

Old Shawneetown is a village in Gallatin County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2010 census, the village had a population of 193, down from 278 at the 2000 census. Located along the Ohio River, Shawneetown served as an important United States ...

, and Suwanee, Georgia

Suwanee is a city in Gwinnett County and a northeastern suburb of Atlanta in the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 15,355; this had grown to an estimated 20,907 as of 2019.

Portions of Forsyth and Fulton counties ...

. Their language became a ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

'' for trade among numerous tribes. They became leaders among the tribes, initiating and sustaining pan-Indian resistance to European and Euro-American expansion.

18th century

Some Shawnee occupied areas in central Pennsylvania. Long without a chief, in 1714 they asked Carondawana, anOneida

Oneida may refer to:

Native American/First Nations

* Oneida people, a Native American/First Nations people and one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy

* Oneida language

* Oneida Indian Nation, based in New York

* Oneida Na ...

war chief, to represent them to the Pennsylvania provincial council. About 1727 Carondawana and his wife, a prominent interpreter known as Madame Montour

Madame Montour (1667 or c. 1685 – c. 1753) was an interpreter, diplomat, and local leader of Algonquin and French Canadian ancestry. Although she was well known, her contemporaries usually referred to her only as "Madame" or "Mrs." Montour. She ...

, settled at Otstonwakin, on the west bank at the confluence of Loyalsock Creek

Loyalsock Creek is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed August 8, 2011 tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River located chiefly in Sullivan and Lycoming counties in ...

and the West Branch Susquehanna River

The West Branch Susquehanna River is one of the two principal branches, along with the North Branch, of the Susquehanna River in the Northeastern United States. The North Branch, which rises in upstate New York, is generally regarded as the exte ...

.

By 1730, European-American settlers began to arrive in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

of Virginia, where the Shawnee predominated in the northern part of the valley. They were claimed as tributaries by the ''Haudenosaunee'' or Six Nations of the Iroquois to the north. The Iroquois had helped some of the Tuscarora people

The Tuscarora (in Tuscarora ''Skarù:ręˀ'', "hemp gatherers" or "Shirt-Wearing People") are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government of the Iroquoian family, with members today in New York, USA, and Ontario, Canada. They c ...

from North Carolina, who were also Iroquoian speaking and distant relations, to resettle in the vicinity of what is now Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

. Most of the Tuscarora migrated to New York and settled near the Oneida people, becoming the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy; they declared their migration finished in 1722. Also at this time, Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

(an Iroquois nation) and Lenape war parties from the north often fought pitched battles with pursuing bands of Catawba Catawba may refer to:

*Catawba people, a Native American tribe in the Carolinas

*Catawba language, a language in the Catawban languages family

*Catawban languages

Botany

* Catalpa, a genus of trees, based on the name used by the Catawba and other ...

from Virginia, who would overtake them in the Shawnee-inhabited regions of the Valley.

By the late 1730s pressure from colonial expansion produced repeated conflicts. Shawnee communities were also impacted by the fur trade. While they gained arms and European goods, they also traded for rum or brandy, leading to serious social problems related to alcohol abuse

Alcohol abuse encompasses a spectrum of unhealthy alcohol drinking behaviors, ranging from binge drinking to alcohol dependence, in extreme cases resulting in health problems for individuals and large scale social problems such as alcohol-relat ...

by their members. Several Shawnee communities in the Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to W ...

, led by Peter Chartier

Peter Chartier (16901759) (Anglicized version of Pierre Chartier, sometimes written Chartiere, Chartiers, Shartee or Shortive) was a fur trader of mixed Shawnee and French parentage. Multilingual, he later became a leader and a band chief among ...

, a métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

trader, opposed the sale of alcohol in their communities. This resulted in a conflict with colonial Governor Patrick Gordon

Patrick Leopold Gordon of Auchleuchries (31 March 1635 – 29 November 1699) was a general and rear admiral in Russia, of Scottish origin. He was descended from a family of Aberdeenshire, holders of the estate of Auchleuchries, near Ellon. The ...

, who was under pressure from traders to allow rum and brandy in trade. Unable to protect themselves, in 1745 some 400 Shawnee migrated from Pennsylvania to Ohio, Kentucky, Alabama and Illinois, hoping to escape the traders' influence.Stephen Warren, ''Worlds the Shawnees Made: Migration and Violence in Early America'', UNC Press Books, 2014Prior to 1754, the Shawnee had a headquarters at Shawnee Springs at modern-day

Cross Junction, Virginia

Cross Junction is an unincorporated community in northern Frederick County, Virginia, United States. Cross Junction is located on the North Frederick Pike ( U.S. Highway 522) at its intersection with Collinsville Road. Cross Junction also encomp ...

. The father of the later chief Cornstalk

Cornstalk (c. 1720? – November 10, 1777) was a Shawnee leader in the Ohio Country in the 1760s and 1770s. His name in the Shawnee language was Hokoleskwa. Little is known about his early life. He may have been born in the Province of Pennsylv ...

held his council there. Several other Shawnee villages were located in the northern Shenandoah Valley: at Moorefield, West Virginia

Moorefield is a town and the county seat of Hardy County, West Virginia, United States. It is located at the confluence of the South Branch Potomac River and the South Fork South Branch Potomac River. Moorefield was originally chartered in 1777; ...

, on the North River; and on the Potomac at Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Allegany County, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its s ...

. In 1753, the Shawnee on the Scioto River

The Scioto River ( ) is a river in central and southern Ohio more than in length. It rises in Hardin County just north of Roundhead, Ohio, flows through Columbus, Ohio, where it collects its largest tributary, the Olentangy River, and meets t ...

in the Ohio Country sent messengers to those still in the Shenandoah Valley, suggesting that they cross the Alleghenies

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

to join the people further west, which they did the following year. The community known as ''Shannoah'' (Lower Shawneetown

Lower Shawneetown, also known as Shannoah or Sonnontio, was an 18th-century Shawnee village located within the Lower Shawneetown Archeological District, near South Portsmouth in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky. The population ...

) on the Ohio River increased to around 1,200 people by 1750.

Ever since the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had claimed the Ohio Country as their hunting ground by right of conquest, and treated the Shawnee and Lenape who resettled there as dependent tribes. Some independent Iroquois bands from various tribes also migrated westward, where they became known in Ohio as the Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

. These three tribes—the Shawnee, the Delaware (Lenape), and the Mingo—became closely associated with one another, despite the differences in their languages. The first two spoke Algonquian languages and the third an Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

language.

After taking part in the first phase of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(also known as "Braddock's War") as allies of the French, the Shawnee switched sides in 1758. They made formal peace with the British colonies at the Treaty of Easton

The Treaty of Easton was a colonial agreement in North America signed in October 1758 during the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) between British colonials and the chiefs of 13 Native American nations, representing tribes of the Iroquois, ...

, which recognized the Allegheny Ridge (the Eastern Divide) as their mutual border. This peace lasted only until Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

erupted in 1763, following Britain's defeat of France and takeover of its territory east of the Mississippi River in North America. Later that year, the Crown issued the Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, legally confirming the 1758 border as the limits of British colonization. They reserved the land beyond for Native Americans. But the Crown had difficulty enforcing the boundary, as Anglo-European colonists continued to move westward.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

in 1768 extended the colonial boundary to the west, giving British colonists a claim to lands in what are now the states of West Virginia and Kentucky. The Shawnee did not agree to this treaty: it was negotiated between British officials and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who claimed sovereignty over the land. While they predominated, the Shawnee and other Native American tribes also hunted there. After the Stanwix treaty, Anglo-Americans began pouring into the Ohio River Valley for settlement, frequently traveling by boats and barges along the Ohio River. Violent incidents between settlers and Indians escalated into Lord Dunmore's War

Lord Dunmore's War—or Dunmore's War—was a 1774 conflict between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations.

The Governor of Virginia during the conflict was John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore—Lord Dunmore. H ...

in 1774. British diplomats managed to isolate the Shawnee during the conflict: the Iroquois and the Lenape stayed neutral. The Shawnee faced the British colony of Virginia with only a few Mingo allies. Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

History

The title was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, second son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. He was made Lord Murray of Blair, Moulin and Tillimet (or Tullimet) and V ...

, royal governor of Virginia, launched a two-pronged invasion into the Ohio Country. The Shawnee chief Cornstalk attacked one wing but fought to a draw in the only major battle of the war, the Battle of Point Pleasant

The Battle of Point Pleasant, also known as the Battle of Kanawha, was the only major action of Dunmore's War. It was fought on October 10, 1774, between the Virginia militia and Shawnee and Mingo warriors. Along the Ohio River near modern-day P ...

. In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte ending the war (1774), Cornstalk and the Shawnee were compelled by the British to recognize the Ohio River as their southern border, which had been established by the Fort Stanwix treaty. By this treaty, the Shawnee ceded all claims to the "hunting grounds" of West Virginia and Kentucky south of the Ohio River. But many other Shawnee leaders refused to recognize this boundary. The Shawnee and most other tribes were highly decentralized, and bands and towns typically made their own decisions about alliances.

American Revolution

When the United States declared independence from the British crown in 1776, the Shawnee were divided. They did not support the American rebel cause. Cornstalk led the minority who wished to remain neutral. The Shawnee north of the Ohio River were unhappy about the American settlement of Kentucky. Colin Calloway reports that most Shawnees allied with the British against the Americans, hoping to be able to expel the settlers from west of the mountains.Colin G. Calloway, "'We Have Always Been the Frontier': The American Revolution in Shawnee Country," ''American Indian Quarterly'' (1992) 16#1 pp 39-52in JSTOR

/ref> War leaders such as

Blackfish

Blackfish is a common name for the following species of fish, dolphins, and whales:

Fish

* Alaska blackfish, (''Dallia pectoralis''), an Esocidae from Alaska, Siberia and the Bering Sea islands

* Black fish (''Carassioides acuminatus'') a cyprin ...

and Blue Jacket

Blue Jacket, or Weyapiersenwah (c. 1743 – 1810), was a war chief of the Shawnee people, known for his militant defense of Shawnee lands in the Ohio Country. Perhaps the preeminent American Indian leader in the Northwest Indian War, i ...

joined Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

and a band of Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

along the lower Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

and Chickamauga Creek

Chickamauga Creek refers to two short tributaries of the Tennessee River, which join the river near Chattanooga, Tennessee. The two streams are North Chickamauga Creek and South Chickamauga Creek, joining the Tennessee from the north and south si ...

against the colonists in that area. Some colonists called this group of Cherokee the Chickamauga Chickamauga may refer to:

Entertainment

* "Chickamauga", an 1889 short story by American author Ambrose Bierce

* "Chickamauga", a 1937 short story by Thomas Wolfe

* "Chickamauga", a song by Uncle Tupelo from their 1993 album ''Anodyne (album), Ano ...

, because they lived along that river at the time of what became known as the Cherokee–American wars

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American se ...

, during and after the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. But they were never a separate tribe, as some accounts suggested.

After the Revolution and during the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

, the Shawnee collaborated with the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

to form a great fighting force in the Ohio Valley. They led a confederation of warriors of Native American tribes in an effort to expel U.S. settlers from that territory. After being defeated by U.S. forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their British allies, against the nascent United States ...

in 1794, most of the Shawnee bands signed the Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, formally titled Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory (now Midwestern United States), including the Wyandot and Delaware peoples, ...

the next year. They were forced to cede large parts of their homeland to the new United States. Other Shawnee groups rejected this treaty, migrating independently to Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, where they settled along Apple Creek. The French called their settlement '' Le Grand Village Sauvage.''

Tecumseh's War and the War of 1812

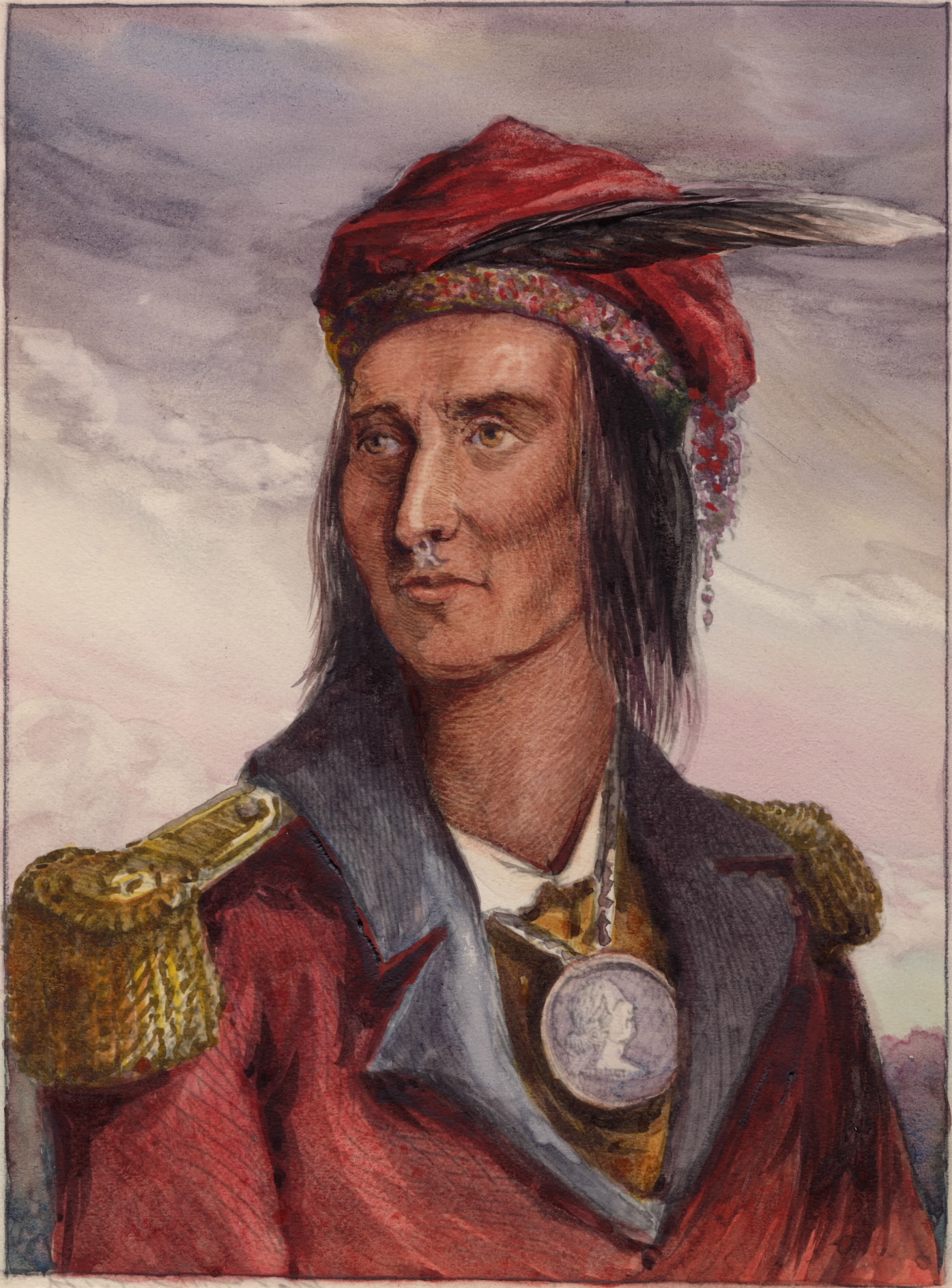

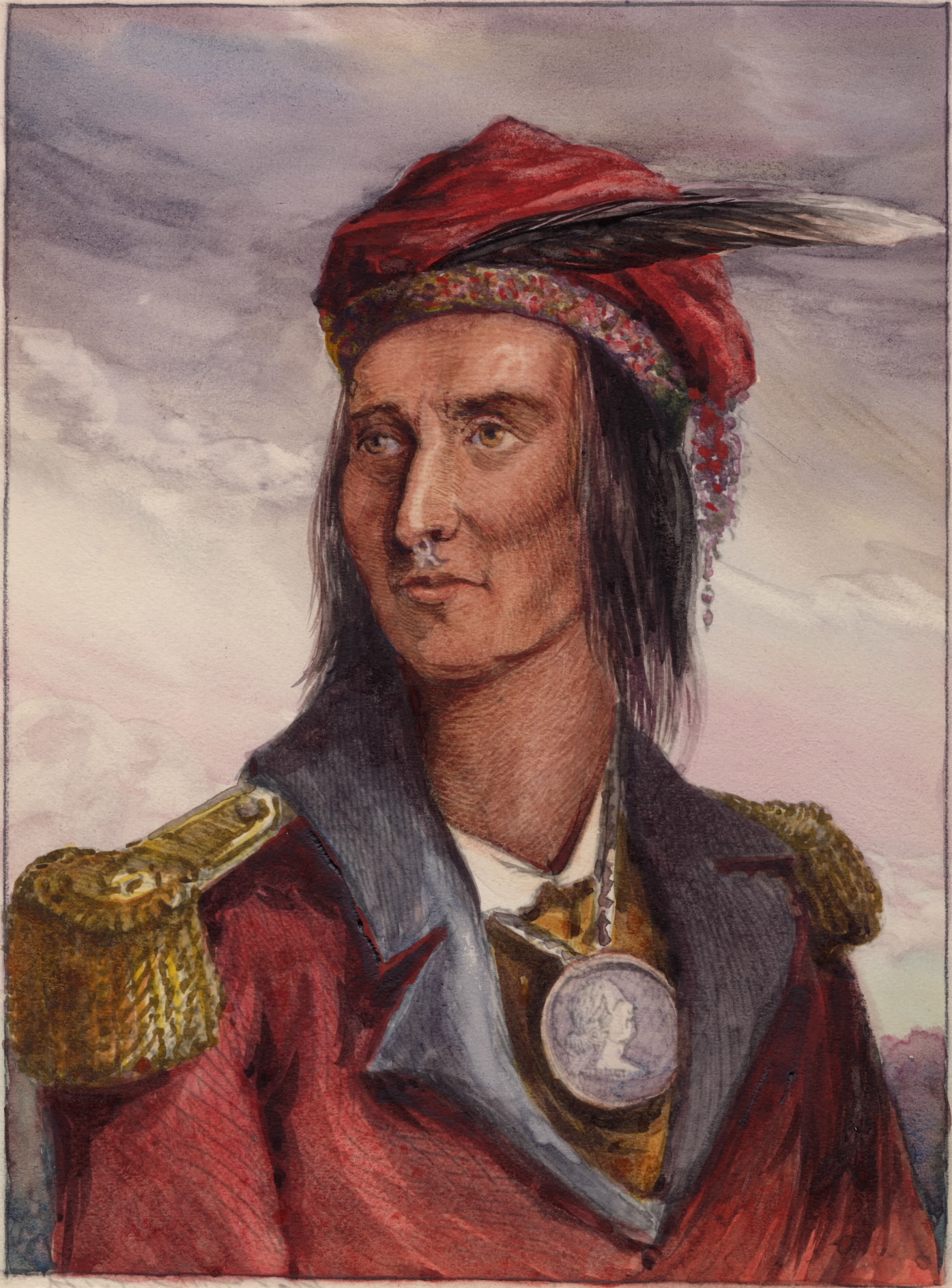

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee leader

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

gained renown for organizing his namesake confederacy to oppose American expansion in Native American lands. The resulting conflict came to be known as Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion was a conflict between the United States and Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh in the Indiana Territory. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Har ...

. The two principal adversaries in the conflict, chief Tecumseh and General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Tecumseh was not among the Native American signers of the Treaty of Greenville. However, many Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville terms, and for the next ten years pan-tribal resistance to American hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

faded.

In September 1809 Harrison, as governor of the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a United States Congress, congressional act that President of the United States, President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an Historic regions of the U ...

, invited the Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

, Lenape, Eel River people, and the Miami to a meeting at Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

. In the negotiations, Harrison promised large subsidies to the tribes if they would cede the lands he was asking for. After two weeks of negotiating, the Potawatomi leaders convinced the Miami to accept the treaty as reciprocity, because the Potawatomi had earlier accepted treaties less advantageous to them at the request of the Miami. Finally the tribes signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne on September 30, 1809, thereby selling the United States over 3,000,000 acres (approximately 12,000 km2), chiefly along the Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

north of Vincennes, Indiana

Vincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the lower Wabash River in the Southwestern Indiana, southwestern part of the state, nearly halfway between Evansville, Indi ...

.

Tecumseh was outraged by the Treaty of Fort Wayne, believing that American Indian land was owned in common by all tribes, an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk people, Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York (state), New York, who was closely associated with Kingdom of Great Britain, Great B ...

.Owens, p. 212 In response, Tecumseh began to expand on the teachings of his brother Tenskwatawa

Tenskwatawa (also called Tenskatawa, Tenskwatawah, Tensquatawa or Lalawethika) (January 1775 – November 1836) was a Native American religious and political leader of the Shawnee tribe, known as the Prophet or the Shawnee Prophet. He was a ...

, a spiritual leader known as The Prophet who called for the tribes to return to their ancestral ways. He began to associate these teachings with the idea of a pan-tribal alliance. Tecumseh traveled widely, urging warriors to abandon accommodationist chiefs and to join the resistance at Prophetstown. In August 1810, Tecumseh led 400 armed warriors to confront Governor Harrison in Vincennes. Tecumseh demanded that Harrison nullify the Fort Wayne treaty, threatening to kill the chiefs who had signed it.Langguth, p. 164 Harrison refused, saying that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so chose.Langguth, p. 165 Tecumseh left peacefully but warned Harrison that he would seek an alliance with the British unless the treaty was nullified.Langguth, p. 166

Great Comet of 1811 and Tekoomsē

In March the

In March the Great Comet of 1811

The Great Comet of 1811, formally designated C/1811 F1, is a comet that was visible to the naked eye for around 260 days, the longest recorded period of visibility until the appearance of Comet Hale–Bopp in 1997. In October 1811, at its bright ...

appeared. During the next year, tensions between American colonists and Native Americans rose quickly. Four settlers were murdered along the Missouri River and, in another incident, natives seized a boatload of supplies from a group of traders. Harrison summoned Tecumseh to Vincennes to explain the actions of his allies. In August 1811, the two leaders met, with Tecumseh assuring Harrison that the Shawnee intended to remain at peace with the United States.

Afterward Tecumseh traveled to the Southeast on a mission to recruit allies against the United States from among the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

." His name ''Tekoomsē'' meant "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across The Sky."

Tecumseh told the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsGreat Spirit

The Great Spirit is the concept of a life force, a Supreme Being or god known more specifically as Wakan Tanka in Lakota,Ostler, Jeffry. ''The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee''. Cambridge University Press, ...

had sent him.

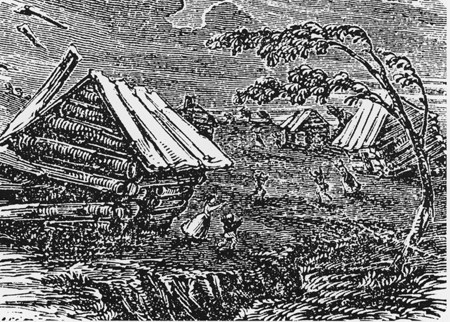

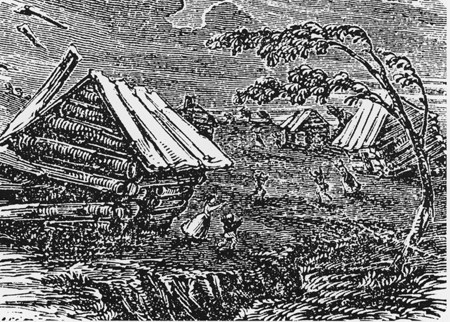

While Tecumseh was traveling, both sides readied for the Battle of Tippecanoe

The Battle of Tippecanoe ( ) was fought on November 7, 1811, in Battle Ground, Indiana, between American forces led by then Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Native American forces associated with Shawnee leader Tecums ...

. Harrison assembled a small force of army regulars and militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to combat the Native forces.Langguth, p. 168 On November 6, 1811, Harrison led this army of about 1,000 men to Prophetstown, Indiana, hoping to disperse Tecumseh's confederacy. Early next morning, forces under The Prophet prematurely attacked Harrison's army at the Tippecanoe River near the Wabash. Though outnumbered, Harrison repulsed the attack, forcing the Natives to retreat and abandon Prophetstown. Harrison's men burned the village and returned home.Langguth, p. 169

New Madrid earthquake

On December 11, 1811, theNew Madrid earthquake

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

shook the Muscogee lands and the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. While the interpretation of this event varied from tribe to tribe, they agreed that the powerful earthquake had to have spiritual significance. The earthquake and its aftershocks helped the Tecumseh resistance movement as the Muscogee and other Native American tribes believed it was a sign that the Shawnee must be supported and that Tecumseh had prophesied such an event and sign.

Tribal involvement in the War of 1812

The Muscogee (Creek) who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the

The Muscogee (Creek) who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the Red Sticks

Red Sticks (also Redsticks, Batons Rouges, or Red Clubs), the name deriving from the red-painted war clubs of some Native American Creeks—refers to an early 19th-century traditionalist faction of these people in the American Southeast. Made u ...

. They were the more conservative and traditional part of the people, as their communities in the Upper Towns were more isolated from European-American settlements. They did not want to assimilate. The Red Sticks rose in resisting the Lower Creek, and the bands became involved in civil war, known as the Creek War

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

. This became part of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

when open conflict broke out between American soldiers and the Red Sticks of the Creek.

After William Hull

William Hull (June 24, 1753 – November 29, 1825) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the American Revolutionary War and was appointed as Governor of Michigan Territory (1805–13), gaining large land cessions from several Ame ...

's surrender of Detroit

The siege of Detroit, also known as the surrender of Detroit or the Battle of Fort Lernoult, Fort Detroit, was an early engagement in the War of 1812. A British force under Major General Isaac Brock with Native Americans in the United States, ...

to the British during the War of 1812, General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

was given command of the U.S. Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was defended by British Colonel Henry Procter, together with Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

and his forces. A detachment of Harrison's army was defeated at Frenchtown along the River Raisin

The River Raisin is a river in southeastern Michigan, United States, that flows through Ice age, glacial sediments into Lake Erie. The area today is an agriculture, agricultural and Industrial sector, industrial center of Michigan. The river flo ...

on January 22, 1813. Some prisoners were taken to Detroit, but Procter left those too injured to travel with an inadequate guard. His Native American allies attacked and killed perhaps as many as 60 wounded Americans, many of whom were Kentucky militiamen. The Americans called the incident the "River Raisin Massacre." The defeat ended Harrison's campaign against Detroit, and the phrase "Remember the River Raisin!" became a rallying cry for the Americans.

In May 1813, Procter and Tecumseh besieged Fort Meigs in northern Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. American reinforcements arriving during the siege were defeated by the Natives, but the garrison in the fort held out. The Indians eventually began to disperse, forcing Procter and Tecumseh to return to Canada. Their second offensive in July against Fort Meigs also failed. To improve Indian morale, Procter and Tecumseh attempted to storm Fort Stephenson, a small American post on the Sandusky River

The Sandusky River ( wyn, saandusti; sjw, Potakihiipi ) is a tributary to Lake Erie in north-central Ohio in the United States. It is about longU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Ma ...

. After they were repulsed with serious losses, the British and Tecumseh ended their Ohio campaign.

On Lake Erie, the American commander Captain Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

fought the Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes called the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, on Lake Erie off the shore of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of the Briti ...

on September 10, 1813. His decisive victory against the British ensured American control of the lake, improved American morale after a series of defeats, and compelled the British to fall back from Detroit. General Harrison launched another invasion of Upper Canada (Ontario), which culminated in the U.S. victory at the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The British ...

on October 5, 1813. Tecumseh was killed there, and his death effectively ended the North American indigenous alliance with the British in the Detroit region. American control of Lake Erie meant the British could no longer provide essential military supplies to their aboriginal allies, who dropped out of the war. The Americans controlled the area during the remainder of the conflict.

Aftermath

The Shawnee in Missouri migrated from the United States south into Mexico, in the eastern part ofSpanish Texas

Spanish Texas was one of the interior provinces of the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1690 until 1821. The term "interior provinces" first appeared in 1712, as an expression meaning "far away" provinces. It was only in 1776 that a lega ...

. They became known as the "Absentee Shawnee

The Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma (or Absentee Shawnee) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Shawnee people. Historically residing in what became organized as the upper part of the Eastern United States, the original Sh ...

." They were joined in the migration by some Delaware (Lenape). Although they were closely allied with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

led by The Bowl, their chief John Linney remained neutral during the 1839 Cherokee War.

Texas achieved independence from Mexico under American leaders. It decided to force removal of the Shawnee from the new republic. But in appreciation of their earlier neutrality, Texan

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by bo ...

President Mirabeau Lamar

Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar (August 16, 1798 – December 25, 1859) was an attorney born in Georgia,

who became a Texas politician, poet, diplomat, and soldier. He was a leading Texas political figure during the Texas Republic era. He was elec ...

fully compensated the Shawnee for their improvements and crops. They were forced out to Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

. The Shawnee settled close to present-day Shawnee, Oklahoma

Shawnee ( sac, Shânîheki) is a city in Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 29,857 in 2010, a 4.9 percent increase from the figure of 28,692 in 2000. The city is part of the Oklahoma Cit ...

. They were joined by Shawnee pushed out of Kansas (see below), who shared their traditionalist views and beliefs.

In 1817, the Ohio Shawnee had signed the Treaty of Fort Meigs

The Treaty of Fort Meigs, also called the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids, formally titled, "Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., 1817", was the most significant Indian treaty by the United States in Ohio since the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. It resulte ...

, ceding their remaining lands in exchange for three reservations in Wapaughkonetta, Hog Creek (near Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

), and Lewistown, Ohio. They shared these lands with some Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

people who had migrated west from New York.

In a series of treaties, including the Treaty of Lewistown

On August 3, 1829, members of the Shawnee Indians and the Seneca Indians signed the Treaty of Lewistown with the United States. In this treaty, Senecas and Shawnees living at Lewistown, Ohio, relinquished their claim to the land and joined the res ...

of 1825, Shawnee and Seneca people

The Seneca () ( see, Onödowáʼga:, "Great Hill People") are a group of indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their n ...

agreed to exchange land in western Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

with the United States for land west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

in what became Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

. In July 1831, the Lewistown group of Seneca–Shawnee departed for the Indian Territory (in present-day Kansas and Oklahoma).

The main body of Shawnee in Ohio followed Black Hoof

Catecahassa or Black Hoof (c. 1740-1831) was the head civil chief of the Shawnee Indians in the Ohio Country of what became the United States. A member of the Mekoche division of the Shawnees, Black Hoof became known as a fierce warrior during ...

, who fought every effort to force his people to give up their homeland. After the death of Black Hoof, the remaining 400 Ohio Shawnee in Wapaughkonetta and Hog Creek surrendered their land and moved to the Shawnee Reserve in Kansas. This movement was largely under terms negotiated by Joseph Parks (1793-1859). He had been raised in the household of Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

and had been a leading interpreter for the Shawnee.

Missouri joined the Union in 1821. After the Treaty of St. Louis in 1825, the 1,400 Missouri Shawnee were forcibly relocated from Cape Girardeau

Cape Girardeau ( , french: Cap-Girardeau ; colloquially referred to as "Cape") is a city in Cape Girardeau and Scott Counties in the U.S. state of Missouri. At the 2020 census, the population was 39,540. The city is one of two principal citie ...

, along the west bank of the Mississippi River, to southeastern Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, close to the Neosho River

The Neosho River is a tributary of the Arkansas River in eastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma in the United States. Its tributaries also drain portions of Missouri and Arkansas. The river is about long.U.S. Geological Survey. National ...

.

During 1833, only Black Bob's band of Shawnee resisted removal. They settled in northeastern Kansas near Olathe and along the Kansas (Kaw) River in Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

near Gum Springs. The Shawnee Methodist Mission

Shawnee Methodist Mission, also known as the Shawnee Mission, which later became the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School, is located in Fairway, Kansas, United States. Designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1968, the Shawnee Metho ...

was built nearby to minister to the tribe. About 200 of the Ohio Shawnee followed the prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

Tenskwatawa

Tenskwatawa (also called Tenskatawa, Tenskwatawah, Tensquatawa or Lalawethika) (January 1775 – November 1836) was a Native American religious and political leader of the Shawnee tribe, known as the Prophet or the Shawnee Prophet. He was a ...

and had joined their Kansas brothers and sisters here in 1826.

In the mid-1830s two companies of Shawnee soldiers were recruited into United States service to fight in the Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

in Florida. One of these was led by Joseph Parks, who had earlier helped negotiate the cession treaty. He was commissioned as captain. Parks was a major landholder in both Westport, Missouri

Westport is a historic neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri, USA. Originally an independent town, it was annexed by Kansas City in 1897. It is one of Kansas City's main entertainment districts.

Westport has a lending library, a branch of the Kans ...

and in Shawnee, Kansas

Shawnee is a city in Johnson County, Kansas, United States. It is the seventh most populous municipality in the Kansas City metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 67,311.

History

Territory of Kansas

Before ...

. He was also a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

. In Shawnee, Kansas, a Shawnee cemetery was started in the 1830s and remained in use until the 1870s. Parks was among the most prominent men buried there.

In the 1853 Indian Appropriations Bill, United States Congress, Congress appropriated $64,366 for treaty obligations to the Shawnee, such as annuities, education, and other services. An additional $2,000 was appropriated for the Seneca and the Shawnee together.

During the American Civil War, Black Bob's band fled from Kansas and joined the "Absentee Shawnee" in Indian Territory to escape the war. After the Civil War, the Shawnee in Kansas were expelled and forced to move to northeastern Oklahoma. The Shawnee members of the former Lewistown group became known as the "Eastern Shawnee".

The former Kansas Shawnee became known as the "Loyal Shawnee" (some say this is because of their allegiance with the Union (American Civil War), Union during the war; others say this is because they were the last group to leave their Ohio homelands). The latter group appeared to be regarded as part of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

Nation by the United States. They were also known as the "Cherokee Shawnee" and were settled on some of the Cherokee land in Indian Territory.

Federal recognition

In the late 20th century, the "Loyal" or "Cherokee" Shawnee began a movement to be federal recognition, federally recognized as a tribe independent of the Cherokee Nation. They received this action by a Congressional bill and are now known as the "Shawnee Tribe

The Shawnee Tribe is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma. Formerly known as the Loyal Shawnee, they are one of three federally recognized Shawnee tribes. The others are the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma and th ...

". Today, most members of the three federally recognized tribes of the Shawnee nation reside in Oklahoma.

Social and kinship groups