SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin (30 September 1893 – 7 July 1973) was an Irish

He came to prominence in the

He came to prominence in the  On 2 February 1921, the Longford IRA ambushed a force of the Auxiliaries on the road at Clonfin, using a mine it had planted. Two lorries were involved, the first blown up, and the second strafed by rapid rifle fire. District Inspector Lt-Cmdr Worthington Craven was hit by two bullets and killed. District Inspector Taylor was shot in the chest and stomach. Four auxiliaries and a driver were killed and eight wounded. The IRA volunteers captured 18 rifles, 20 revolvers and a Lewis gun. At the

On 2 February 1921, the Longford IRA ambushed a force of the Auxiliaries on the road at Clonfin, using a mine it had planted. Two lorries were involved, the first blown up, and the second strafed by rapid rifle fire. District Inspector Lt-Cmdr Worthington Craven was hit by two bullets and killed. District Inspector Taylor was shot in the chest and stomach. Four auxiliaries and a driver were killed and eight wounded. The IRA volunteers captured 18 rifles, 20 revolvers and a Lewis gun. At the

He resigned from the Army in 1929, and was elected at a by-election to

He resigned from the Army in 1929, and was elected at a by-election to

'The SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin Story' by Padraic O'Farrell (1981)

'Blacksmith of Ballinalee: Sean Mac Eoin' by Padraic O'Farrell (1993)

Witness Statement of SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin submitted to the Bureau of Military History in 1955

40 minute interview with Mac EoinMini-documentary about the capture of Mac Eoin in Mullingar, March 1921Biography of Mac Eoin at seanmaceoin.ieSeĂ¡n Mac Eoin papers

* {{DEFAULTSORT:MacEoin, Sean 1893 births 1973 deaths Candidates for President of Ireland Chiefs of Staff of the Defence Forces (Ireland) Cumann na nGaedheal TDs Early Sinn FĂ©in TDs Fine Gael TDs Irish prisoners sentenced to death Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Members of the 2nd DĂ¡il Members of the 3rd DĂ¡il Members of the 6th DĂ¡il Members of the 7th DĂ¡il Members of the 8th DĂ¡il Members of the 9th DĂ¡il Members of the 10th DĂ¡il Members of the 11th DĂ¡il Members of the 12th DĂ¡il Members of the 13th DĂ¡il Members of the 14th DĂ¡il Members of the 15th DĂ¡il Members of the 16th DĂ¡il Members of the 17th DĂ¡il Ministers for Defence (Ireland) Ministers for Justice (Ireland) National Army (Ireland) generals People of the Irish Civil War (Pro-Treaty side) Politicians from County Longford Military personnel from County Longford Prisoners sentenced to death by the United Kingdom United Irish League

Fine Gael

Fine Gael (, ; English: "Family (or Tribe) of the Irish") is a liberal-conservative and Christian-democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of DĂ¡il Ă ...

politician and soldier who served as Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

briefly in 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, Minister for Justice A Ministry of Justice is a common type of government department that serves as a justice ministry.

Lists of current ministries of justice

Named "Ministry"

* Ministry of Justice (Abkhazia)

* Ministry of Justice (Afghanistan)

* Ministry of Just ...

from 1948 to 1951, and Chief of Staff of the Defence Forces from February 1929 to October 1929. He served as a Teachta DĂ¡la

A Teachta DĂ¡la ( , ; plural ), abbreviated as TD (plural ''TDanna'' in Irish, TDs in English), is a member of DĂ¡il Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament). It is the equivalent of terms such as ''Member of Parli ...

(TD) from 1921 to 1923, and from 1929 to 1965.

He was commonly referred to as the "Blacksmith of Ballinalee".

Early life

He was born John Joseph McKeon on 30 September 1893 at Bunlahy,Granard

Granard () is a town in the north of County Longford, Ireland, and has a traceable history going back to AD 236. It is situated just south of the boundary between the watersheds of the Shannon and the Erne, at the point where the N55 nationa ...

, County Longford

County Longford ( gle, Contae an Longfoirt) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was 46,6 ...

, the eldest son of Andrew McKeon and Katherine Treacy. After a national school education, he trained as a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

at his father's forge and, on his father's death in February 1913, he took over the running of the forge and the maintenance of the McKeon family. He moved to Kilinshley in the Ballinalee

Ballinalee (), sometimes known as Saint Johnstown, is a village in north County Longford, Ireland. It is situated on the River Camlin, and falls within the civil parish of Clonbroney. As of the 2016 census, the village had a population of 347 ...

district of County Longford to set up a new forge.

He had joined the United Irish League

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto ''"The Land for the People"''. Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazi ...

in 1908. Mac Eoin's Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

activities began in earnest in 1913, when he joined the Clonbroney Company of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

. Late that year he was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

and joined the Granard

Granard () is a town in the north of County Longford, Ireland, and has a traceable history going back to AD 236. It is situated just south of the boundary between the watersheds of the Shannon and the Erne, at the point where the N55 nationa ...

circle of the organization.

IRA leader

War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of o ...

as leader of an Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) 'flying column

A flying column is a small, independent, military land unit capable of rapid mobility and usually composed of all arms. It is often an ''ad hoc'' unit, formed during the course of operations.

The term is usually, though not necessarily, appli ...

'. In November 1920, he led the Longford brigade in attacking Crown forces in Granard during one of the periodic government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

reprisals, forcing them to retreat to their barracks. On 31 October, Inspector Philip St John Howlett Kelleher of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, ConstĂ¡blacht RĂoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

(RIC) was shot dead in Kiernan's Greville Arms Hotel in Granard. Members of the British Auxiliary Division

The Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC), generally known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, was a paramilitary unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the Irish War of Independence. It was founded in July 1920 by Major ...

set fire to parts of the town. The next day, Mac Eoin held the village of Ballinalee situated on the Longford Road between Longford and Granard. They stood against superior British forces, forcing them to retreat and abandon their ammunition. In a separate attack on 8 November, Mac Eoin led his men against the RIC at Ballinalee. An eighteen-year-old Constable Taylor was killed. Constable E Shateford and two others were wounded. The story was that the small garrison sang "God Save the King

"God Save the King" is the national anthem, national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in ...

" as they took up positions to return fire.

On the afternoon of 7 January 1921, a joint Royal Irish Constabulary and British Army patrol consisting of ten policemen led by an Inspector, with a security detachment of nine soldiers, appeared on Anne Martin's street. Mac Eoin's own testimony at his trial (which was not contested by any parties present) states that:

The casualties from this incident were District Inspector Thomas McGrath killed, and a police constable wounded.'Guerrilla Warfare in the Irish War of Independence, 1919-1921', by Joseph McKenna (Pub. McFarland, 2014).

On 2 February 1921, the Longford IRA ambushed a force of the Auxiliaries on the road at Clonfin, using a mine it had planted. Two lorries were involved, the first blown up, and the second strafed by rapid rifle fire. District Inspector Lt-Cmdr Worthington Craven was hit by two bullets and killed. District Inspector Taylor was shot in the chest and stomach. Four auxiliaries and a driver were killed and eight wounded. The IRA volunteers captured 18 rifles, 20 revolvers and a Lewis gun. At the

On 2 February 1921, the Longford IRA ambushed a force of the Auxiliaries on the road at Clonfin, using a mine it had planted. Two lorries were involved, the first blown up, and the second strafed by rapid rifle fire. District Inspector Lt-Cmdr Worthington Craven was hit by two bullets and killed. District Inspector Taylor was shot in the chest and stomach. Four auxiliaries and a driver were killed and eight wounded. The IRA volunteers captured 18 rifles, 20 revolvers and a Lewis gun. At the Clonfin Ambush

The Clonfin Ambush was an ambush carried out by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 2 February 1921, during the Irish War of Independence. It took place in the townland of Clonfin (or Cloonfin) between Ballinalee and Granard in County Longford. ...

, Mac Eoin ordered his men to care for the wounded British, at the expense of captured weaponry. This earned him both praise and criticism, but became a big propaganda boost for the war effort, especially in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. He was admired by many within the IRA for leading practically the only effective column in the midlands. In July 1920, he was among the majority of commanders who were prepared to sign the Agreement recognizing the Volunteers as the Army of the Republic. The Oath of Allegiance was "for the purpose of ratifying under the Agreement under which the Volunteers came under the control of the Dail".

On 5 February 1921, ''The Anglo-Celt

''The Anglo-Celt'' () is a weekly local newspaper published every Thursday in Swellan, Cavan, Ireland, founded in 1846. It exclusively contains local news about Cavan and surroundings. The news coverage of the paper is mainly based on the pape ...

'' ran an article claiming the discovery of the body of William Chalmers, a local Protestant farmer. Mr Elliott was also a farmer, whose body was found on 30 January, lying face down in a bog.

Mac Eoin was captured at Mullingar

Mullingar ( ; ) is the county town of County Westmeath in Ireland. It is the third most populous town in the Midland Region, with a population of 20,928 in the 2016 census.

The Counties of Meath and Westmeath Act 1543 proclaimed Westmeat ...

railway station in March 1921, imprisoned and sentenced to death for the murder of an RIC District Inspector McGrath in the shooting at Anne Martin's street in January 1921.

Mac Eoin's family forge was near Currygrane, County Longford, the family home of Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

, the British CIGS. In June 1921, Wilson was petitioned for clemency by MacEoin's mother (who referred to her son as "John" in her letter), by his own brother Jemmy, and by the local Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

vicar, and passed on the appeals out of respect for the latter two individuals. Three auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties such as garrison troops, u ...

had already given character references on his behalf after he had treated them chivalrously at the Clonfin Ambush

The Clonfin Ambush was an ambush carried out by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 2 February 1921, during the Irish War of Independence. It took place in the townland of Clonfin (or Cloonfin) between Ballinalee and Granard in County Longford. ...

in February 1921. However, Nevil Macready

General Sir Cecil Frederick Nevil Macready, 1st Baronet, (7 May 1862 – 9 January 1946), known affectionately as Make-Ready (close to the correct pronunciation of his name), was a British Army officer. He served in senior staff appointments in ...

, British Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, confirmed the death sentence; he described Mac Eoin as "nothing more than a murderer", and wrote that he was probably responsible for other "atrocities", but also later recorded in his memoirs that Mac Eoin was the only IRA man he had met, apart from Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

, to have a sense of humour. His second-in-command was from North Roscommon. Sean Connolly had a colourful career as head of Leitrim brigade.

Mac Eoin wrote the following letter to his friend (and classmate at Moyne Latin School) Father Jim Sheridan, a combatant in the Old IRA and a 'flying column' member, who had been ordained and sent to Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

to study theology:

According to Oliver St. John Gogarty

Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty (17 August 1878 – 22 September 1957) was an Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist. He served as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's novel ...

, Charles Bewley

Charles Henry Bewley (12 July 1888 – 1969) was an Irish diplomat.

Raised in a famous Dublin Quaker business family, he embraced Irish Republicanism and Roman Catholicism. He was the Irish envoy to Berlin who reportedly thwarted efforts to obta ...

wrote Mac Eoin's death-sentence speech. Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

organised a rescue attempt. Six IRA Volunteers, led by Paddy O'Daly and Emmet Dalton

James Emmet Dalton MC (4 March 1898 – 4 March 1978) was an Irish soldier and film producer. He served in the British Army in the First World War, reaching the rank of captain. However, on his return to Ireland he became one of the senior fig ...

, captured a British armoured car and, wearing British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

uniforms, gained access to Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, PrĂosĂºn Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History

...

. However, Mac Eoin was not in the part of the jail they believed, and after some shooting, the party retreated.

Within days, Mac Eoin was elected to DĂ¡il Éireann

DĂ¡il Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

at the 1921 general election, as a TD for Longford–Westmeath.

He was eventually released from prison — along with all other members of the DĂ¡il, after Collins threatened to break off treaty negotiations with the British government unless he were freed. It was rumoured that Sean Mac Eoin was to be the best man at Collins' wedding.

Treaty and the Civil War

In the debate on theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, Mac Eoin seconded Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ă“ GrĂobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn FĂ©in. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

's motion that it should be accepted.

Mac Eoin joined the National Army and was appointed GOC Western Command in June 1922. During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

he pacified the west of Ireland for the new Free State, marching overland to Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Developing around a 13th century castle of the de Barry family, de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal poi ...

and linking up with a seaborne expedition that landed at Westport, County Mayo

Westport (, historically anglicised as ''Cahernamart'') is a town in County Mayo in Ireland.Westport Before 1800 by Michael Kelly published in Cathair Na Mart 2019 It is at the south-east corner of Clew Bay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean on th ...

. His military career soared thereafter: he was appointed GOC Curragh Training Camp in August 1925, Quartermaster General in March 1927, and Chief of Staff in February 1929.

Political career

He resigned from the Army in 1929, and was elected at a by-election to

He resigned from the Army in 1929, and was elected at a by-election to DĂ¡il Éireann

DĂ¡il Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

for the Leitrim–Sligo constituency, representing Cumann na nGaedheal

Cumann na nGaedheal (; "Society of the Gaels") was a political party in the Irish Free State, which formed the government from 1923 to 1932. In 1933 it merged with smaller groups to form the Fine Gael party.

Origins

In 1922 the pro-Treaty G ...

. At the 1932 general election, he returned to the constituency of Longford–Westmeath, and—with the merging of Cumann na nGaedheal into Fine Gael

Fine Gael (, ; English: "Family (or Tribe) of the Irish") is a liberal-conservative and Christian-democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of DĂ¡il Ă ...

—continued to serve the Longford area as TD in either Longford–Westmeath (1932–37, 1948–65) or Athlone–Longford (1937–48) until he was defeated at the 1965 general election.

During a long political career he served as Minister for Justice A Ministry of Justice is a common type of government department that serves as a justice ministry.

Lists of current ministries of justice

Named "Ministry"

* Ministry of Justice (Abkhazia)

* Ministry of Justice (Afghanistan)

* Ministry of Just ...

(February 1948 – March 1951) and Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

(March–June 1951) in the First Inter-Party Government

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

, and again as Minister for Defence (June 1954 – March 1957) in the Second Inter-Party Government

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of Time in physics, time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally t ...

.

He unsuccessfully stood twice as candidate for the office of President of Ireland

The president of Ireland ( ga, UachtarĂ¡n na hÉireann) is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces.

The president holds office for seven years, and can ...

, against SeĂ¡n T. O'Kelly

SeĂ¡n Thomas O'Kelly ( ga, SeĂ¡n TomĂ¡s Ă“ Ceallaigh; 25 August 1882 – 23 November 1966), originally John T. O'Kelly, was an Irish Fianna FĂ¡il politician who served as the second president of Ireland from June 1945 to June 1959. He also serve ...

in 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. It is also the only year in which nuclear weapons have been used in combat.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

Januar ...

, and Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

in 1959

Events January

* January 1 - Cuba: Fulgencio Batista flees Havana when the forces of Fidel Castro advance.

* January 2 - Lunar probe Luna 1 was the first man-made object to attain escape velocity from Earth. It reached the vicinity of E ...

.

The attempt at freeing him from jail is referenced in the Jack Higgins novel The Eagle Has Landed.

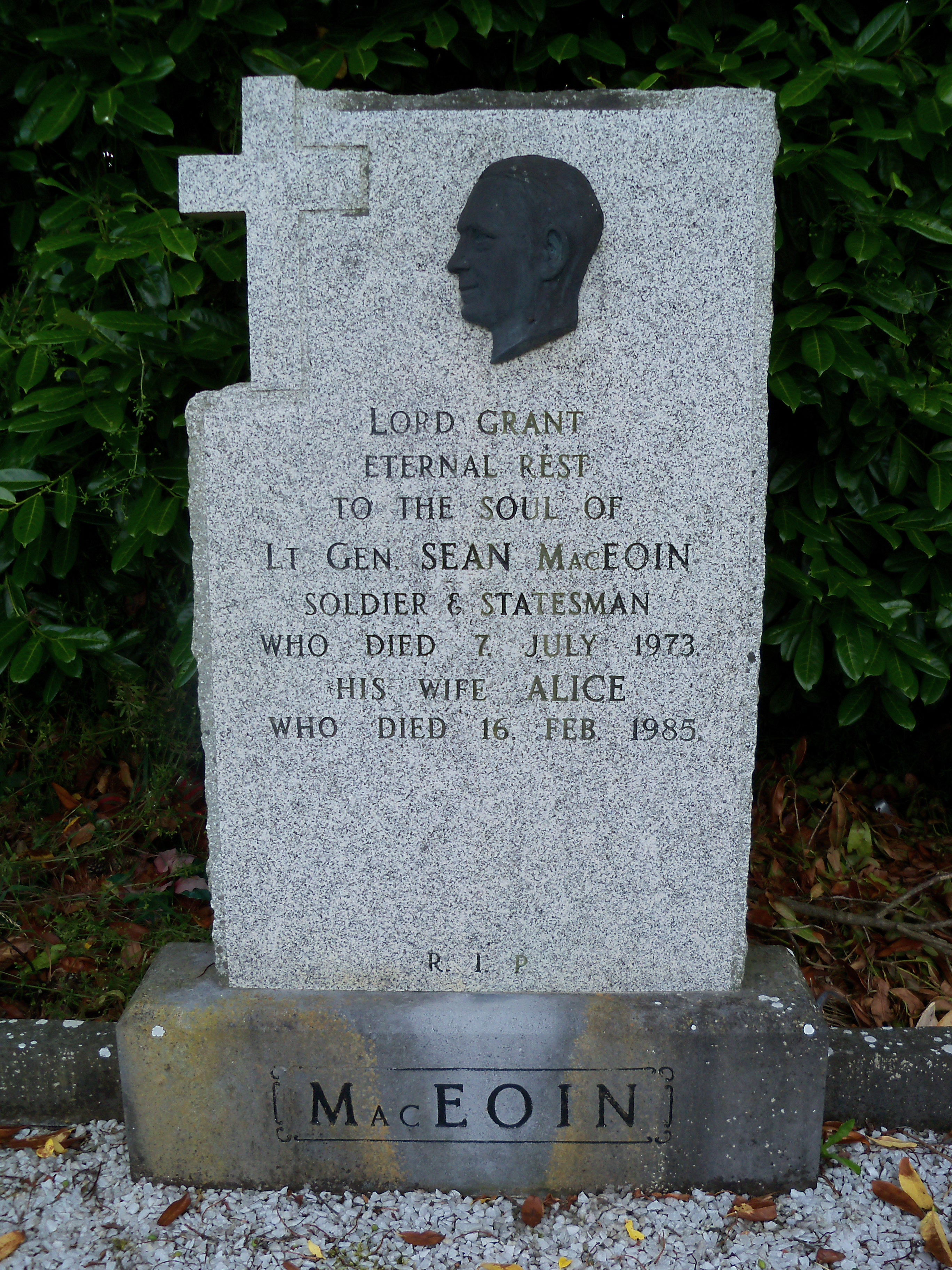

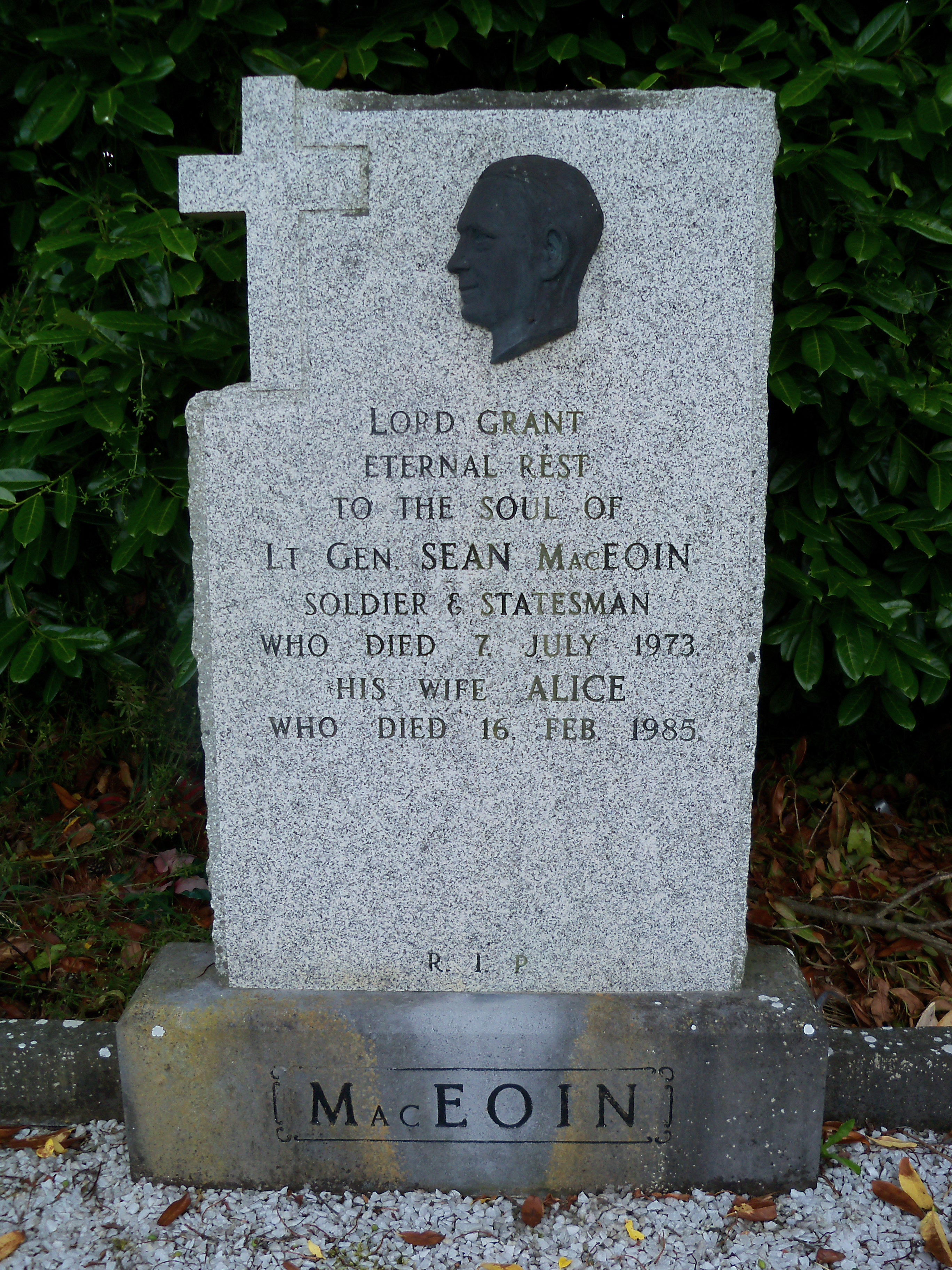

Mac Eoin retired from public life after the 1965 general election, and died on 7 July 1973. He married Alice Cooney on 21 June 1922, at a ceremony attended by Griffith and Collins; she died on 16 February 1985. They had no children.

Legacy

On 16 June 2013, during the 'General Sean MacEoin Commemoration Weekend', a statue of Mac Eoin was unveiled in his home town of Ballinalee; on the same day a plaque was unveiled in Bunlahy, his birthplace. Both the statue and the plaque were unveiled byEnda Kenny

Enda Kenny (born 24 April 1951) is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 2011 to 2017, Leader of Fine Gael from 2002 to 2017, Minister for Defence from May to July 2014 and 2016 to 2017, Leader of the Opposition from ...

, the then Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of DĂ¡il Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

, who laid a wreath at the statue.

The forge that he worked in is still standing and is known as 'Mac Eoin forge'.

Bibliography

'The SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin Story' by Padraic O'Farrell (1981)

'Blacksmith of Ballinalee: Sean Mac Eoin' by Padraic O'Farrell (1993)

Witness Statement of SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin submitted to the Bureau of Military History in 1955

References

* * Lawlor, Pearse, ''1920-1922: The Outrages'' (Cork 2011) * MacEoin, Uinseann (ed.), ''Survivors'' (Dublin 1980) * O'Farrel, Padraic, ''The SeĂ¡n Mac Eoin Story'' (Mercier Press, Cork 1981)External links

40 minute interview with Mac Eoin

* {{DEFAULTSORT:MacEoin, Sean 1893 births 1973 deaths Candidates for President of Ireland Chiefs of Staff of the Defence Forces (Ireland) Cumann na nGaedheal TDs Early Sinn FĂ©in TDs Fine Gael TDs Irish prisoners sentenced to death Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Members of the 2nd DĂ¡il Members of the 3rd DĂ¡il Members of the 6th DĂ¡il Members of the 7th DĂ¡il Members of the 8th DĂ¡il Members of the 9th DĂ¡il Members of the 10th DĂ¡il Members of the 11th DĂ¡il Members of the 12th DĂ¡il Members of the 13th DĂ¡il Members of the 14th DĂ¡il Members of the 15th DĂ¡il Members of the 16th DĂ¡il Members of the 17th DĂ¡il Ministers for Defence (Ireland) Ministers for Justice (Ireland) National Army (Ireland) generals People of the Irish Civil War (Pro-Treaty side) Politicians from County Longford Military personnel from County Longford Prisoners sentenced to death by the United Kingdom United Irish League