Seyfo Genocide on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of

In its millet system, the Ottoman Empire recognized

In its millet system, the Ottoman Empire recognized

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van;

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van;

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district ( sanjak), including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox. Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notable residents, including the Chaldean bishop

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district ( sanjak), including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox. Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notable residents, including the Chaldean bishop

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor

In Tur Abdin, some Syriac Christians fought their attempted extermination. This was considered treason by Ottoman officials, who reported massacre victims as rebels. Christians in

In Tur Abdin, some Syriac Christians fought their attempted extermination. This was considered treason by Ottoman officials, who reported massacre victims as rebels. Christians in

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the

During the journey to Hamadan, the Assyrians were harassed by Kurdish irregulars (probably at the instigation of Simko and

During the journey to Hamadan, the Assyrians were harassed by Kurdish irregulars (probably at the instigation of Simko and

In 1919, Assyrians attended the

In 1919, Assyrians attended the

For Assyrians, the Sayfo is considered the greatest modern example of their persecution. Eyewitness accounts of the genocide were typically passed down orally, rather than in writing; memories were often passed down in lamentations. After large-scale migration to Western countries (where Assyrians had greater

For Assyrians, the Sayfo is considered the greatest modern example of their persecution. Eyewitness accounts of the genocide were typically passed down orally, rather than in writing; memories were often passed down in lamentations. After large-scale migration to Western countries (where Assyrians had greater

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

/ Syriac Christians

Syriac Christianity ( syr, адÐùÐöÐùÐòШÐê УÐòЙÐùÐùШÐê / ''M≈°i·∏•oyu·πØo Suryoyto'' or ''M≈°i·∏•ƒÅy≈´·π؃ŠSuryƒÅytƒÅ'') is a distinctive branch of Eastern Christianity, whose formative theological writings and traditional liturgies are expr ...

in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish tribes during World War I.

The Assyrians were divided into mutually antagonistic churches, including the Syriac Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = St_George_Syriac_orthodox_church_in_Damascus.jpg

, imagewidth = 250

, alt = Cathedral of Saint George

, caption = Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus ...

, the Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ЕÐïШÐê ÐïаÐïТÐöÐê, '' øƒí·∏ètƒÅ d-Ma·∏èen·∏•ƒÅ'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

, and the Chaldean Catholic Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = Assyrian Church.png

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Our Lady of Sorrows Baghdad, Iraq

, abbreviation =

, type ...

. Before World War I, they lived in mountainous and remote areas of the Ottoman Empire (some of which were effectively stateless). The empire's nineteenth-century centralization efforts led to increased violence and danger for the Assyrians.

Mass killing of Assyrian civilians began during the Ottoman occupation of Azerbaijan from January to May 1915, during which massacres were committed by Ottoman forces and pro-Ottoman Kurds. In Bitlis province, Ottoman troops returning from Persia joined local Kurdish tribes to massacre the local Christian population (including Assyrians). Ottoman forces and Kurds attacked the Assyrian tribes of Hakkari Hakkari or Hakk√¢ri may refer to:

*Hakkari (historical region), a historical region in modern-day Turkey and Iraq

*Hakk√¢ri (city), a city and the capital of Hakk√¢ri Province, Turkey

*Hakk√¢ri Province

Hakk√¢ri Province (, tr, Hakk√¢ri ili, ...

in mid-1915, driving them out by September despite the tribes mounting a coordinated military defense. Governor Mehmed Reshid initiated a genocide of all of the Christian communities in Diyarbekir province, including Syriac Christians, facing only sporadic armed resistance in some parts of Tur Abdin. Ottoman Assyrians living farther south, in present-day Iraq and Syria, were not targeted in the genocide.

The Sayfo occurred concurrently with and was closely related to the Armenian genocide, although the Sayfo is considered to have been less systematic. Local actors played a larger role than the Ottoman government, but the latter also ordered attacks on certain Assyrians. Motives for killing included a perceived lack of loyalty among some Assyrian communities to the Ottoman Empire and the desire to appropriate their land. At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

, the Assyro-Chaldean delegation said that its losses were 250,000 (about half the prewar population); the accuracy of this figure is unknown. They later revised their estimate to 275,000 dead at the Lausanne Conference in 1923. The Sayfo is less studied than the Armenian genocide. Efforts to have it recognized as a genocide began during the 1990s, spearheaded by the Assyrian diaspora. Although several countries acknowledge that Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire were victims of a genocide, this assertion is rejected by the Turkish government.

Terminology

There is no universally accepted translation in English for theendonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

''Suryoyo'' or ''Suryoye''. The choice of which term to use, such as ''Assyrian'', ''Syriac'', ''Aramean

The Arameans ( oar, ê§Äê§ìê§åê§âê§Ä; arc, ê°Äê°ìê°åê°âê°Ä; syc, ÐêЙÃàаÐùÐê, ƒÄrƒÅmƒÅyƒì) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean h ...

'', and ''Chaldean'', is often determined by political alignment. The Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ЕÐïШÐê ÐïаÐïТÐöÐê, '' øƒí·∏ètƒÅ d-Ma·∏èen·∏•ƒÅ'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

was the first to adopt an identity derived from ancient Assyria. The Syriac Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = St_George_Syriac_orthodox_church_in_Damascus.jpg

, imagewidth = 250

, alt = Cathedral of Saint George

, caption = Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus ...

has officially rejected the use of ''Assyrian'' since 1952, although not all Syriac Orthodox reject Assyrian identity. Since the Ottoman Empire was organized by religion, Ottoman officials referred to populations by their religious affiliation rather than ethnicity. Therefore, according to historian David Gaunt, "speaking of an 'Assyrian Genocide' is anachronistic". In Neo-Aramaic

The Neo-Aramaic or Modern Aramaic languages are varieties of Aramaic that evolved during the late medieval and early modern periods, and continue to the present day as vernacular (spoken) languages of modern Aramaic-speaking communities. Within ...

, the languages historically spoken by Assyrians, it has been known since 1915 as ''Sayfo'' or ''Seyfo'' (, ), which, since the tenth century, has also meant 'extermination' or 'extinction'. Other terms used by some Assyrians include '' nakba'' (Arabic for catastrophe) and ''firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farm√¢n; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

'' (Turkish for order, as Assyrians believed that they were killed according to an official decree).

Background

The people now calledAssyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

, Chaldean, or Aramean are native to Upper Mesopotamia and historically spoke Aramaic languages, and their ancestors converted to Christianity in the first centuries CE. The first major schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

in Syriac Christianity

Syriac Christianity ( syr, адÐùÐöÐùÐòШÐê УÐòЙÐùÐùШÐê / ''M≈°i·∏•oyu·πØo Suryoyto'' or ''M≈°i·∏•ƒÅy≈´·π؃ŠSuryƒÅytƒÅ'') is a distinctive branch of Eastern Christianity, whose formative theological writings and traditional liturgies are expr ...

dates to 410, when Christians in the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

( Persia) formed the Church of the East to distinguish themselves from the official religion of the Roman Empire. The West Syriac church (later the Syriac Orthodox Church) was persecuted by Roman rulers for theological differences but remained separate from the Church of the East. The schisms in Syriac Christianity were fueled by political divisions between empires and personal antagonism between clergymen. Middle Eastern Christian

Christianity, which originated in the Middle East during the 1st century AD, is a significant minority religion within the region, characterized by the diversity of its beliefs and traditions, compared to Christianity in other parts of the ...

communities were devastated by the Crusades and the Mongol invasions. The Chaldean and Syriac Catholic Church

The Syriac Catholic Church ( syc, ЕÐïШÐê УÐòЙÐùÐùШÐê ЩШÐòÐÝÐùЩÐùШÐê, øƒ™·πØo Suryay·πØo Qa·πØolƒ´qay·πØo, ar, ÿߟџɟܟäÿ≥ÿ© ÿߟÑÿ≥ÿ±Ÿäÿߟܟäÿ© ÿߟџÉÿßÿ´ŸàŸÑŸäŸÉŸäÿ©) is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Christianity ...

es split from the Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church, respectively, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and entered into full communion

Full communion is a communion or relationship of full agreement among different Christian denominations that share certain essential principles of Christian theology. Views vary among denominations on exactly what constitutes full communion, but ...

with the Catholic Church. Each church considered the others heretical.

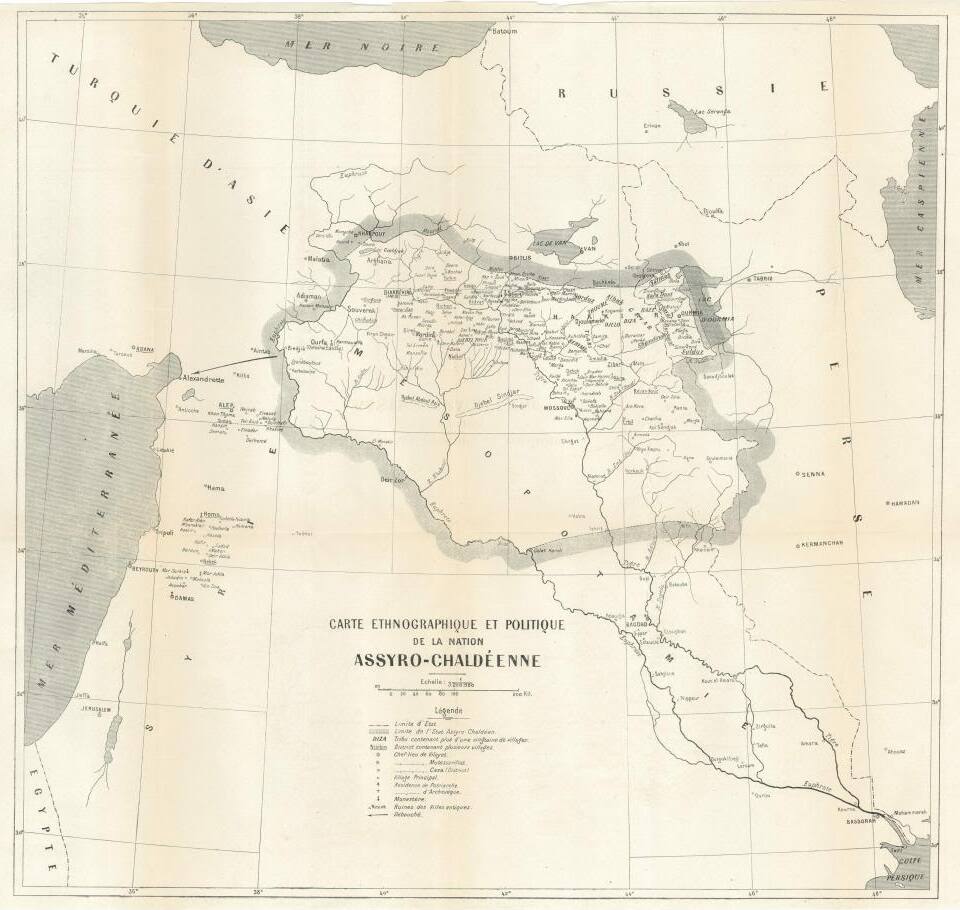

Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire

religious denominations

A religious denomination is a subgroup within a religion that operates under a common name and tradition among other activities.

The term refers to the various Christian denominations (for example, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic, and the many variet ...

rather than ethnic groups: Süryaniler / Yakubiler (Syriac Orthodox or Jacobites), Nasturiler (Church of the East or Nestorians), and Keldaniler (Chaldean Catholic Church). Until the nineteenth century, these groups were part of the Armenian millet. Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire lived in remote, mountainous areas, where they had settled to avoid state control. Although this remoteness enabled Assyrians to avoid military conscription and taxation, it also cemented internal differences and prevented the emergence of a collective identity similar to the Armenian national movement. Unlike the Armenians, Syriac Christians did not control a disproportionate part of Ottoman commerce and did not have significant populations in nearby hostile countries.

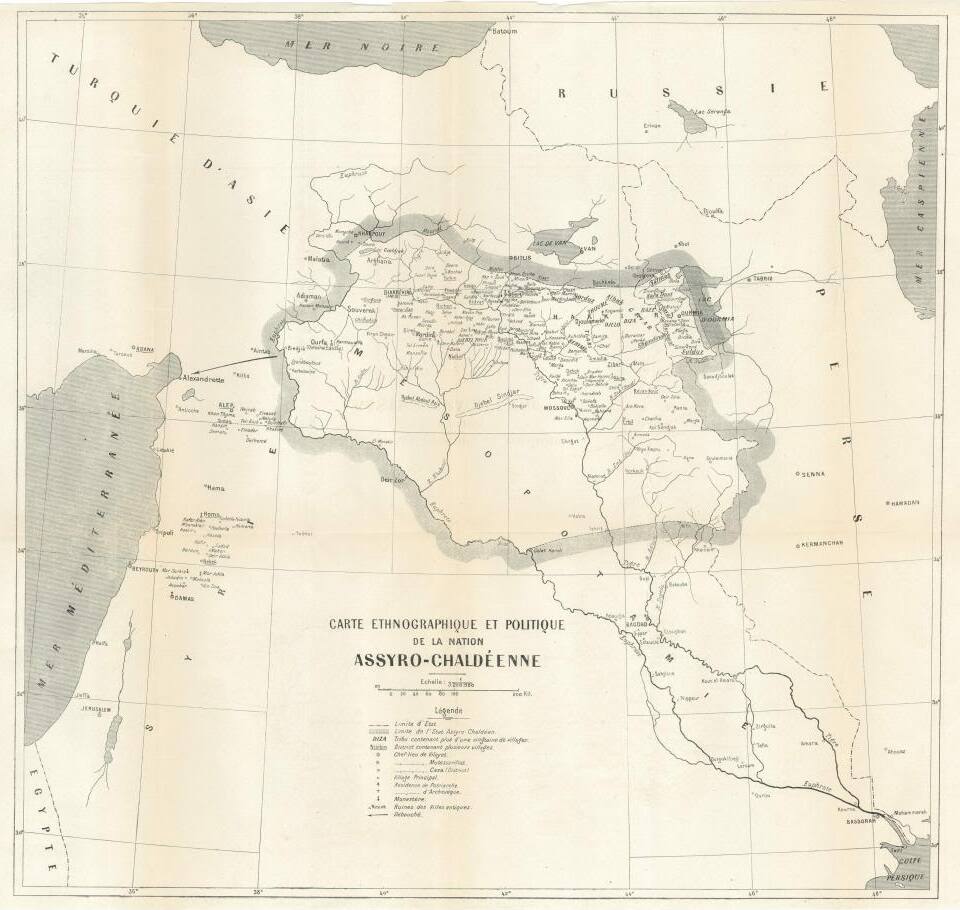

There were no accurate estimates of the prewar Assyrian population, but Gaunt gives a possible figure of 500,000 to 600,000. Midyat

Midyat ( ku, Midyad, Syriac: аÐïÐùÐï ''M√´·∏èya·∏è'', Turoyo: ''Mi·∏èyoyo'', ar, ŸÖÿØŸäÿßÿ™) is a town in the Mardin Province of Turkey. The ancient city is the center of a centuries-old Hurrian town in Upper Mesopotamia. In its long history, the ...

, in Diyarbekir province ( vilayet), was the only town in the Ottoman Empire with an Assyrian majority (Syriac Orthodox, Chaldeans, and Protestants). Syriac Orthodox Christians were concentrated in the hilly rural areas around Midyat, known as Tur Abdin, where they lived in almost 100 villages and worked in agriculture or crafts. Syriac Orthodox culture was centered in two monasteries near Mardin

Mardin ( ku, M√™rd√Æn; ar, ŸÖÿßÿ±ÿØŸäŸÜ; syr, аЙÐïÐùТ, Merdƒ´n; hy, ’Ñ’°÷Ä’§’´’∂) is a city in southeastern Turkey. The capital of Mardin Province, it is known for the Artuqid architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on ...

(west of Tur Abdin): Mor Gabriel and Deyrulzafaran

Mor Hananyo Monastery ( tr, Deyr√ºzzafer√¢n Manastƒ±rƒ±, syr, ÐïÐùЙÐê ÐïаЙÐù ÐöТТÐùÐê; ''Monastery of Saint Ananias'') is an important Syriac Orthodox monastery located three kilometers south east of Mardin, Turkey, in the Syriac cultural re ...

. Outside the core area of Syriac settlement, there were also sizable populations in villages and the towns of Urfa, Harput, and Adiyaman. Unlike the Syriac population of Tur Abdin, many of these Syriacs spoke non-Aramaic languages.

Under the Qudshanis-based Patriarch of the Church of the East, Assyrian tribes

The following is a list of Assyrian clans or tribes of northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and northwestern Iran.

Tribes

* Nerwa tribe

* Albaq Tribe

* Alqosh Tribe

* Barwar Tribe

* Baz tribe

* Botan tribe

* Chal Tr ...

controlled the Hakkari Hakkari or Hakk√¢ri may refer to:

*Hakkari (historical region), a historical region in modern-day Turkey and Iraq

*Hakk√¢ri (city), a city and the capital of Hakk√¢ri Province, Turkey

*Hakk√¢ri Province

Hakk√¢ri Province (, tr, Hakk√¢ri ili, ...

mountains east of Tur Abdin (adjacent to the Ottoman–Persian border). Hakkari is very mountainous, with peaks reaching and separated by steep gorges; many areas were only accessible by footpaths carved into the mountainsides. The Assyrian tribes sometimes fought each other on behalf of their Kurd ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian peoples, Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Ir ...

ish allies. Church of the East settlement began in the east on the western shore of Lake Urmia in Persia; a Chaldean enclave was just north, in Salamas

Salmas ( fa, ÿ≥ŸÑŸÖÿßÿ≥; ; ; ; syr, УеÐÝеаеУ, Salamas) is the capital of Salmas County, West Azerbaijan Province in Iran. It is located northwest of Lake Urmia, near Turkey. According to the 2019 census, the city's population is 127,864. ...

. There was a Chaldean area around Siirt in Bitlis province (northeast of Tur Abdin and northwest of Hakkari, less mountainous than Hakkari), but most Chaldeans lived farther south in present-day Iraq.

Worsening conflicts

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a stateless region

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held p ...

. The first mass violence targeting Assyrians was in the mid-1840s, when Kurdish emir Badr Khan

Bedir Khan Beg (Kurmanji: ''Bedirxan Beg'', tr, Bedirhan Bey; 1803–1869) was the last Kurdish Mîr and mütesellim of the Emirate of Botan.

Hereditary head of the house of Rozhaki whose seat was the ancient Bitlis castle and descended from S ...

devastated Hakkari and Tur Abdin, killing several thousands. During intertribal feuds, the bulk of the violence was directed at Christian villages under the protection of the opposing tribe.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed the Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When the Kurds refused to return the weapons at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were at a disadvantage and subject to increasing violence. The irregular Hamidiye cavalry were formed in the 1880s from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government; their exemption from civil and military law enabled them to commit acts of violence with impunity. The rise of political Islam in the form of Kurdish shaikhs also widened the divide between the Assyrians and the Muslim Kurds. Many Assyrians were killed in the 1895 massacres of Diyarbekir. Violence worsened after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, despite Assyrian hopes that the new government would stop promoting anti-Christian Islamism. In 1908, 12,000 Assyrians were expelled from the Lizan valley by the Kurdish emir of Barwari. Due to increasing Kurdish attacks which Ottoman authorities did nothing to prevent, Patriarch of the Church of the East Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin began negotiations with the Russian Empire before World War I.

World War I

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist Caucasian

Caucasian may refer to:

Anthropology

*Anything from the Caucasus region

**

**

** ''Caucasian Exarchate'' (1917–1920), an ecclesiastical exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus region

*

*

*

Languages

* Northwest Caucasian l ...

Muslims and Armenians, as well as Assyrians and Azeris in Persia, and Russia looked to the Armenians, Kurds, and Assyrians living in the Ottoman Empire. Prior to the war, Russia controlled parts of northeastern Persia, including Azerbaijan and Tabriz.

Like other genocides, the Sayfo had a number of causes. The rise of nationalism led to competing Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

, Kurdish, Persian, and Arab national movement

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

s, which contributed to increasing violence in the already conflict-ridden borderlands inhabited by the Assyrians. Historian Donald Bloxham emphasizes the negative influence of European powers interfering in the Ottoman Empire under the premise of protecting Ottoman Christians. This imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

put the Ottoman Christians at risk of retaliatory attacks. In 1912 and 1913, the Ottoman loss in the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

triggered an exodus of Muslim refugees from the Balkans. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government decided to resettle the refugees in eastern Anatolia, on land confiscated from populations deemed disloyal to the empire. There was a direct connection between the deportation of the Christian population and the resettlement of Muslims in the depopulated areas. The goals of the population replacement were to Turkify

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

the Balkan Muslims and end the perceived internal threat from the Christian populations. With local politicians predisposed to violence against non-Muslims, these factors helped generate the preconditions for genocide.

CUP politician Enver Pasha

İsmail Enver, better known as Enver Pasha ( ota, اسماعیل انور پاشا; tr, İsmail Enver Paşa; 22 November 1881 – 4 August 1922) was an Ottoman military officer, revolutionary, and convicted war criminal who formed one-third ...

set up the paramilitary Special Organization, which was loyal to himself. Its members, many of whom were convicted criminals released from prison for the task, operated as spies and saboteurs. The Ottoman Empire ordered a full mobilization for war on 24 July 1914, and concluded the German–Ottoman alliance shortly thereafter. In August 1914, the CUP sent a delegation to an Armenian conference offering an autonomous Armenian region if the Armenian Revolutionary Federation incited a pro-Ottoman revolt in Russia in the event of war. The Armenians refused; according to Gaunt, a similar offer was probably made to Mar Shimun in Van

A van is a type of road vehicle used for transporting goods or people. Depending on the type of van, it can be bigger or smaller than a pickup truck and SUV, and bigger than a common car. There is some varying in the scope of the word across th ...

on 3 August. After returning to Qudshanis, Enver Pasha sent letters urging his followers to "fulfill strictly all their duties to the Turks". The Assyrians in Hakkari (like many other Ottoman subjects) resisted conscription into the Ottoman army during the mobilization, and many fled to Persia in August. Those in Mardin

Mardin ( ku, M√™rd√Æn; ar, ŸÖÿßÿ±ÿØŸäŸÜ; syr, аЙÐïÐùТ, Merdƒ´n; hy, ’Ñ’°÷Ä’§’´’∂) is a city in southeastern Turkey. The capital of Mardin Province, it is known for the Artuqid architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on ...

, however, accepted conscription.

Ethnic cleansing of Hakkari

Massacres of lowland Assyrians

In August 1914, Assyrians in nine villages near the border were forced to flee to Persia and their villages were burned after they refused to join the Ottoman army. On 26 October 1914, a few days before the Ottoman Empire entered World War I, Ottoman interior ministerTalaat Pasha

Mehmed Talaat (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha,; tr, Talat Paşa, links=no was an Ottoman politician and convicted war criminal of the late Ottoman Empire who served as its leader from 1913 t ...

sent a telegram to Djevdet Bey, the governor of Van province (which included Hakkari). In a planned Ottoman attack in Persia, the loyalty of the Hakkari Assyrians was doubted. Talaat ordered the deportation and resettlement of the Assyrians who lived near the Persian border with Muslims farther west; no more than twenty Assyrians would live in each resettlement, destroying their culture, language, and traditional way of life. Gaunt cites this order as the beginning of the Sayfo. The government in Van reported that the order could not be implemented due to the lack of forces to carry it out, and by 5 November the expected Assyrian unrest did not materialize. Assyrians in Julamerk and Gawar were arrested or killed, and Ottoman irregulars attacked Assyrian villages throughout Hakkari in retaliation for their refusal to follow the order. The Assyrians, unaware of the government's role in these events until December 1914, protested to the governor of Van.

The Ottoman garrison in the border town of Bashkale was commanded by Kazim Karabekir, and the local Special Organization branch by . Russian forces captured Bashkale and Sarai in November 1914 and held both for a few days. After their recapture by the Ottomans, the towns' local Christians were punished as collaborators, out of proportion to any actual collaboration. Local Ottoman forces consisting of gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

, Hamidiye irregulars, and Kurdish volunteers were unable to mount attacks on the Assyrian tribes on the highlands, confining their attacks to poorly-armed Christian villages in the plains. Refugees from the area told the Russian army that "nearly the entire male Christian population of Gawar and Bashkale" had been massacred. In May 1915, Ottoman forces retreating from Bashkale massacred hundreds of Armenian women and children before continuing to Siirt.

Preparations for war

Mar Shimun learned about the massacre of Assyrians in lowland areas, and believed that the highland tribes would be next. Via Agha Petros, an Assyrian interpreter for the Russian consulate in Urmia, he contacted the Russian authorities. Shimun traveled to Bashkale to meetMehmed Shefik Bey

Mehmed (modern Turkish: Mehmet) is the most common Bosnian and Turkish form of the Arabic name Muhammad ( ar, محمد) (''Muhammed'' and ''Muhammet'' are also used, though considerably less) and gains its significance from being the name of Muha ...

, an Ottoman official sent from Mardin to win over the Assyrians for the Ottoman cause, in December 1914. Shefik promised protection and money in exchange for a written promise that the Assyrians would not side with Russia or permit their tribes to take up arms against the Ottoman government. The tribal chiefs considered the offer, but rejected it. In January 1915, Kurds blocked the route from Qudshanis to the Assyrian tribes. The patriarch's sister, Lady Surma, left Qudshanis the following month with 300 men. Early in 1915, the tribes of Hakkari were preparing to defend themselves from a large-scale attack; they decided to send women and children to the area around Chamba in Upper Tyari

Tyari ( syr, ÐõÐùеЙÐπÐê, ·π¨yƒÅrƒì) is an Assyrian tribe and a historical district within Hakkari, Turkey. The area was traditionally divided into Upper (''Tyari Letha'') and Lower Tyari (''Tyari Khtetha'')‚Äìeach consisting of several Assyrian ...

, leaving only combatants behind. On 10 May, the Assyrian tribes met and declared war (or a general mobilization) against the Ottoman Empire. In June, Mar Shimun traveled to Persia to ask for Russian support. He met with General Fyodor Chernozubov

Fyodor Grigoryevich Chernozubov (14 September 1863 – 14 November 1919; sometimes seen as Theodore G. Chernozubov) was a Russian Imperial Army officer who became lieutenant general on 20 February 1915. He was trained at Page Corps and later Imp ...

in Moyanjik (in the Salmas valley), who promised support. The patriarch and Agha Petros also met Russian consul Basil Nikitin Basil Nikitin (1 January 1885 – 7 June 1960) was a Russian orientalist and diplomat.

Basil Nikitin was born in Sosnowiec, a town in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Nikitin's family had several Orientalists. Therefore, he developed an in ...

in Salmas shortly before 21 June, but the promised Russian help never materialized.

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van;

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van; Haydar Bey

Haydar ( ar, حيدر), also spelt Hajdar, Hayder, Heidar, Haider, Heydar, and other variants, is an Arabic male given name, also used as a surname, meaning "lion". In Islamic tradition, the name is primarily associated with Ali, Ali ibn Abi Ta ...

, the governor of Mosul, was given the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands". The ethnic-cleansing operation was coordinated by Enver, Talaat, and military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul province. The Ottoman army joined local Kurdish tribes against specific targets. Suto Agha of the Kurdish Oramar tribe attacked Jilu, Dez, and Baz from the east; Said Agha attacked a valley in Lower Tyari; Ismael Agha targeted Chamba in Upper Tyari, and the Upper Berwar emir attacked Ashita, the Lizan valley, and Lower Tyari from the west.

Invasion of the highlands

The joint encirclement operation was launched on 11 June. The Jilu tribe was attacked at the beginning of the campaign by several Kurdish tribes; the fourth-century church ofMar Zaya

Mar, mar or MAR may refer to:

Culture

* Mar or Mor, an honorific in Syriac

* Earl of Mar, an earldom in Scotland

* MAA (singer) (born 1986), Japanese

* Marathi language, by ISO 639-2 language code

* March, as an abbreviation for the third mon ...

, with historic artifacts, was destroyed. Ottoman forces based in Julamerk and Mosul launched a joint attack on Tyari on 23 June. Haydar first attacked the Tyari villages of Ashita and Sarespido; later, an expeditionary force of three thousand Turks and Kurds attacked the mountain pass between Tyari and Tkhuma. Although the Assyrians were victorious in most of the battles, they had unsustainable losses of lives and ammunition and lacked their invaders' German-manufactured rifles, machine guns, and artillery. In July, Mar Shimun sent Malik Khoshaba and bishop Mar Yalda Yahwallah from Barwari to Tabriz in Persia to request urgent assistance from the Russians. The Kurdish Barzani tribe assisted the Ottoman army and laid waste to Tkhuma, Tyari, Jilu, and Baz. During the campaign, Ottoman forces took no prisoners. Mar Shimun's brother, Hormuz, was arrested while he was studying in Constantinople; in late June, Talaat tried to obtain the surrender of the Assyrian tribes by threatening Hormuz' life if Mar Shimun did not capitulate. The Assyrians refused, and he was killed.

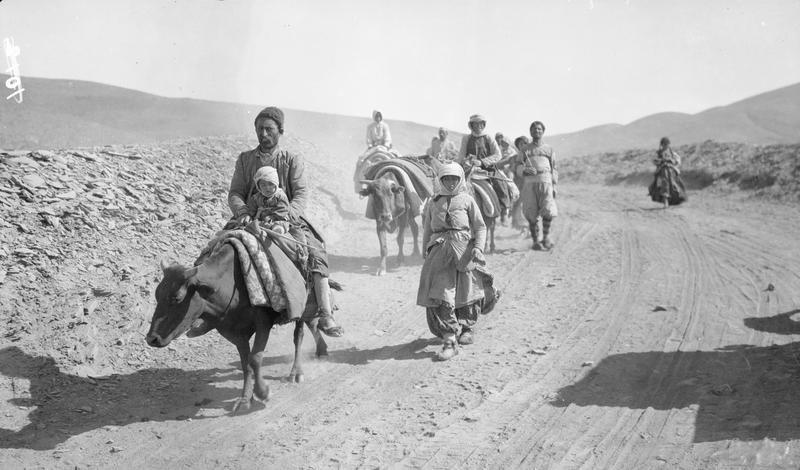

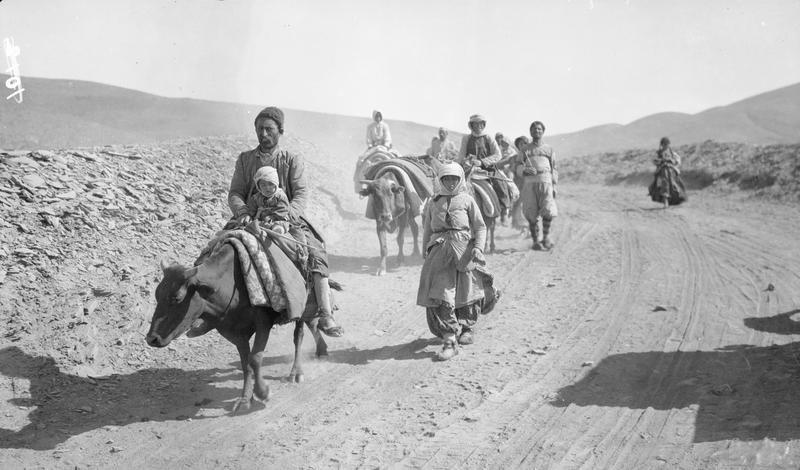

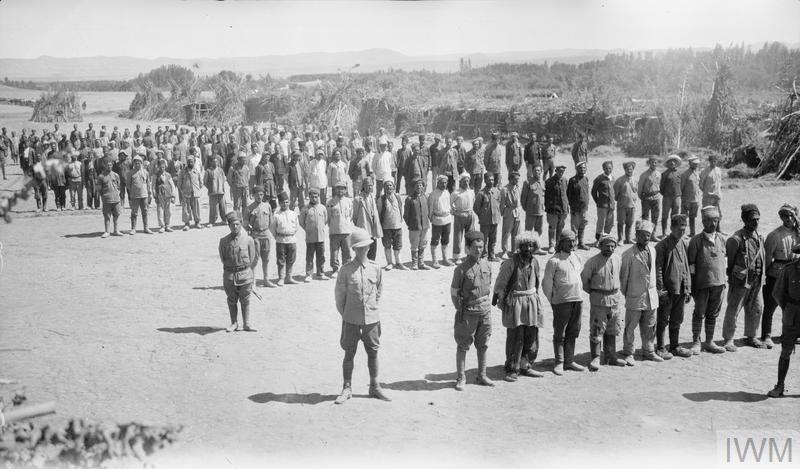

Outnumbered and outgunned, the Assyrians retreated further into the high mountains without food and watched as their homes, farms, and herds were pillaged. They had no other option but fleeing to Persia, which most had done by September. Most of the men joined the Russian army, hoping to return home. During the 1915 fighting, the Assyrians' only strategic objective was defensive; the Ottoman goal was to defeat the Assyrian tribes and prevent their return.

Ottoman occupation of Azerbaijan

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente

Entente, meaning a diplomatic "understanding", may refer to a number of agreements:

History

* Entente (alliance), a type of treaty or military alliance where the signatories promise to consult each other or to cooperate with each other in case o ...

, and marched in Urmia. Agha Petros later said that he had been promised by Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war. Ottoman irregulars in Van province crossed the Persian border, attacking Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in Khoy, Tabriz, and Urmia and expelled Sunni Muslims

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

. Ottoman authorities retaliated with the expulsion of several thousand Hakkari Assyrians to Persia. Resettled in farming villages, the Assyrians were armed by Russia. The Russian government was aware that the Assyrians and Armenians of Azerbaijan could not stop an Ottoman army, and was indifferent to the danger to which these communities would be exposed in an Ottoman invasion.

On 1 January 1915, Russia abruptly withdrew its forces. Ottoman forces led by Djevdet, Kazim Karabekir, and Ömer Naji occupied Azerbaijan with no opposition. Immediately after the withdrawal of Russian forces, local Muslims committed pogroms against Christians; the Ottoman army also attacked Christian civilians. Over a dozen villages were sacked and, of the large villages, only Gulpashan

Golpashan was an Assyrian Christian town located on the western shore of Lake Urmia. The town was once one of the most prosperous towns in Urmia plains but was destroyed and abandoned in 1918. The site is now occupied by the village of Gol Pashin. ...

was left intact. News of the atrocities spread quickly, leading many Armenians and Assyrians to flee to the Russian Caucasus; those north of Urmia had more time to flee. According to several estimates, about 10,000 or 15,000 to 20,000 crossed the border into Russia. Assyrians who had volunteered for the Russian forces were separated from their families, who were often left behind. An estimated 15,000 Ottoman troops reached Urmia by 4 or 5 January, and Dilman on 8 January.

Massacres

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

protested the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.

Many Christians did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal, and 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were stranded in Urmia. Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the city's Presbyterian and Lazarist

, logo =

, image = Vincentians.png

, abbreviation = CM

, nickname = Vincentians, Paules, Lazarites, Lazarists, Lazarians

, established =

, founder = Vincent de Paul

, fou ...

missions. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease. Between February and May (when the Ottoman forces pulled out), there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia. More than 100 men were arrested at the Lazarist compound, and dozens (including Mar Dinkha, bishop of Tergawer) were executed on 23 and 24 February. Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked; men were killed, and women and children were abducted and raped.

There were no missionaries in the Salmas valley to protect Christians, although some local Muslims tried to do so. In Dilman, the Persian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians; he was forced to surrender the men to Ottoman forces, however, who executed them in the town square. The Ottoman forces lured Christians to Haftevan (a village south of Dilman) by demanding that they register there, and arrested notable people in Dilman who were brought to the village for execution. Over two days in February, 700 to 800 people (including the entire male Christian population) was murdered in Haftevan. The killings were committed by the Ottoman army (led by Djevdet) and the local Shekak

The Shekak (also Shakkak, Shikakan or Shekkāk; ; ) is a Kurdish tribe present in various regions, mainly in West Azerbaijan province, Iran.

History

The Shikaki tribe are first mentioned in a Yezidi mişûr (manuscript) from 1207 AD, where the ...

Kurdish tribe, led by Simko Shikak.

In April, Ottoman army commander Halil Pasha

Halil Pasha (also known as Bostancı Halil Pasha) was an Ottoman statesman who served as the governor of Ottoman Egypt from 1631 to 1633. He was known for his "gentle, impartial, and prosperous administration"d'Avennes, Prisse (1983) ''Arab art ...

arrived in Azerbaijan with reinforcements from Rowanduz. Halil and Djevdet ordered the murder of Armenian and Syriac soldiers serving in the Ottoman army, and several hundred were killed. In several other massacres in Azerbaijan in early 1915, hundreds of Christians were killed and women were targeted for kidnapping and rape; seventy villages were destroyed. In May and June, Christians who had fled to the Caucasus returned to find their villages destroyed. Armenian and Assyrian volunteers attacked Muslims in revenge. After retreating from Persia, Ottoman forces—blaming Armenians and Assyrians for their defeat—took revenge against Ottoman Christians. Ottoman atrocities in Persia were widely covered by international media in mid-March 1915, prompting a declaration on 24 May by Russia, France, and the United Kingdom condemning them. The Blue Book, a collection of eyewitness reports of Ottoman atrocities published by the British government in 1916, devoted 104 of its 684 pages to the Assyrians.

Butcher battalion in Bitlis

A Kurdish rebellion in Bitlis province was suppressed shortly before the outbreak of war in November 1914. The CUP government reversed its previous opposition to the Hamidiye regiments, recruiting them to put down the rebellion. As elsewhere, military requisitions became pillage; in February, labor-battalion recruits began to disappear. In July and August 1915, 2,000 Chaldeans and Syriac Orthodox from Bitlis were among those who fled to the Caucasus when the Russian army retreated from Van. Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district ( sanjak), including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox. Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notable residents, including the Chaldean bishop

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district ( sanjak), including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox. Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notable residents, including the Chaldean bishop Addai Sher

Addai Sher ( syr, ÐêÐïÐù дÐùЙ, ) Also spelled Adda√Ø Scher and Addai Sheir (3 March 1867 ‚Äì 21 June 1915), was the Chaldean Catholic archbishop of Siirt in Upper Mesopotamia. He was killed by the Ottomans during the 1915 Assyrian genocide.

Ear ...

. After retreating from Persia, Djevdet led the siege of Van; he continued to Bitlis province in June with 8,000 soldiers, whom he called the "butcher battalion" ( tr, kassablar taburu). The arrival of these troops in Siirt led to more violence. District governor ( mutasarrif) Serfiçeli Hilmi Bey and Siirt mayor Abdul Ressak were replaced because they did not support the killing. Forty local officials in Siirt organized the massacres.

During the month-long massacre, Christians were killed in the streets or their houses (which were looted). The Chaldean diocese of Siirt was destroyed, including its library of rare manuscripts. The massacre was organized by Bitlis governor Abdülhalik Renda

Mustafa Abdülhalik Renda (29 November 1881 – 1 October 1957) was a Turkish civil servant and politician of Tosk Albanian descent.

Biography

Renda was born in Yanya, in the Janina Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. Renda was of Albanian orig ...

, the chief of police, the mayor, and other prominent local residents. The killing in Siirt was committed by ''çetes

Çetes were Muslim armed Irregular military, irregular Brigandage, brigands who were active in Anatolia, Asia Minor after World War I. They were notorious for their assaults on Orthodoxy, Christian Orthodox Armenian genocide, Armenians, Greek ge ...

'', and the surrounding villages were destroyed by Kurds; many local Kurdish tribes were involved. According to Venezuelan mercenary Rafael de Nogales, the massacre was planned as revenge for Ottoman defeats by Russia. De Nogales believed that Halil was trying to assassinate him, since the CUP had disposed of other witnesses. He left Siirt as quickly as he could, passing deportation columns of Syriac and Armenian women and children.

Only 400 people were deported from Siirt; the remainder were killed or kidnapped by Muslims. The deportees (women and children, since the men had been executed) were forced to march west from Siirt towards Mardin or south towards Mosul, assaulted by police. As they passed through, their possessions (including their clothes) were stolen by local Kurds and Turks. Those unable to keep up were killed, and women considered attractive were abducted by police or Kurds, raped, and killed. One site of attacks and robbery by Kurds was the gorge of Wadi Wawela in Sawro kaza, northeast of Mardin. No deportees reached Mardin, and only 50 to 100 Chaldeans (of an original 7,000 to 8,000) reached Mosul. Three Assyrian villages in Siirt—Dentas, Piroze and Hertevin

Hertevin, officially Ekindüzü, (, ) is a village in the Pervari District of Siirt Province in Turkey.

It was one of the last Assyrian villages in the country prior to Sayfo. The village is now populated by Kurds and had a population of 315 in ...

—survived the Sayfo, existing until 1968 when their residents emigrated.

After leaving Siirt, Djevdet proceeded to Bitlis and arrived on 25 June. His forces killed men, and the women and girls were enslaved by Turks and Kurds. The Syriac Orthodox Church estimated its Bitlis province losses at 8,500, primarily in Schirwan and Gharzan.

Diyarbekir

The situation for Christians in Diyarbekir province worsened during the winter of 1914–1915; the Saint Ephraim church was vandalized, and four young men from the Syriac village of Qarabash (near Diyarbekir) were hanged for desertion. Syriacs who protested the executions were clubbed by police, and two died. In March, many non-Muslim soldiers were disarmed and transferred to road-building labor battalions. Harsh conditions, mistreatment, and individual murders led to many deaths. On 25 March, CUP founding member Mehmed Reshid was appointed governor of Diyarbekir. Chosen for his record of anti-Armenian violence, Reshid brought thirty Special Organization members (mainly Circassians) who were joined by released convicts. Many local officials ( kaymakams and district governors) refused to follow Reshid's orders, and were replaced in May and June 1915. Kurdish confederations were offered rewards to allow their Syriac clients to be killed. Government allies complied (including the Milli and Dekşuri), and many who had supported the anti-CUP1914 Bedirhan revolt

This year saw the beginning of what became known as World War I, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It als ...

switched sides because the extermination of Christians did not threaten their interests. The Raman tribe became enthusiastic executioners for Reshid, but parts of the Heverkan leadership protected Christians; this limited Reshid's genocide, and allowed pockets of resistance to survive in Tur Abdin. Some Yazidis, who were also persecuted by the government, aided the Christians. The killers in Diyarbekir were typically volunteers organized by local leaders, and the freelance perpetrators took a share of the loot. Some women and children were abducted into local Kurdish or Arab families.

Thousands of Armenians and several hundred Syriacs (including all their clergymen) in Diyarbekir city were arrested, deported, and massacred in June. In the Viranşehir kaza, west of Mardin, its Armenians were massacred in late May and June 1915. Syriacs were not killed, but many lost their property and some were deported to Mardin in August. In total, 178 Syriac towns and villages near Diyarbekir were wiped out and most of them razed.

Targeting of non-Armenian Christians

Under Reshid's leadership, a systematic anti-Christian extermination was conducted in Diyarbekir province which included Syriacs and the province's few Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholics. Reshid knew that his decision to extend the persecution to all Christians in Diyarbekir was against the central government's wishes, and he concealed relevant information from his communications. Unlike the government, Reshid and his Mardin deputy Bedri Bey classified all Aramaic-speaking Christians as Armenians: enemies of the CUP who must be eliminated. Reshid planned to replace Diyarbekir's Christians with selected, approved Muslim settlers to counterbalance the potentially-rebellious Kurds; in practice, however, the areas were resettled by Kurds and the genocide consolidated the province's Kurdish presence. Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör says that in Diyarbekir, "most instances of massacre in which the militia engaged were directly ordered by" Reshid and "all Christian communities of Diyarbekir were equally hit by the genocide, although the Armenians were often particularly singled out for immediate destruction". The priest Jacques Rhétoré estimated that the Syriac Orthodox in Diyarbekir province lost 72 percent of their population, compared to 92 percent ofArmenian Catholics

, native_name_lang = hy

, image = St Elie - St Gregory Armenian Catholic Cathedral.jpg

, imagewidth = 260px

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Saint Elias and Saint Gregory the Illuminat ...

and 97 percent of Armenian Apostolic Church adherents.

German diplomats noticed that the Ottoman deportations were targeting groups other than Armenians, leading to a complaint from the German government. Austria–Hungary and the Holy See also protested the violence against non-Armenians. Talaat Pasha telegraphed Reshid on 12 July 1915 that "measures adopted against the Armenians are absolutely not to be extended to other Christians... you are ordered to put an immediate end to these acts". No action was taken against Reshid for exterminating Syriac Christians or assassinating Ottoman officials who disagreed with the massacres, however, and in 1916 he was appointed governor of Ankara. Talaat's telegram may have been sent in response to German and Austrian opposition to the massacres, with no expectation of implementation. The perpetrators began separating Armenians and Syriacs in early July, only killing the former; however, the killing of Syriacs resumed in August and September.

Mardin district

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor Hilmi Bey Hilmi ( ar, حلمي) is a masculine Arabic given name, it may refer to:

* Hilmi Esat Bayındırlı (born 1962), Turkish*American para-skier

*Hilmi Güler (born 1946), Turkish politician and metallurgical engineer

* Hilmi İşgüzar (born 1929), Tu ...

. Hilmi rejected Reshid's demands to arrest Christians in Mardin, saying that they posed no threat to the state. Reshid sent Pirinççizâde Aziz Feyzi to incite anti-Christian violence in April and May, and Feyzi bribed or persuaded the Deşi, Mışkiye, Kiki and Helecan chieftains to join him. Mardin police chief Memduh Bey arrested dozens of men in early June, using torture to extract confessions of treason and disloyalty and extorting money from their families. Reshid appointed a new mayor and officials in Mardin, who organized a 500-man militia to kill. He also urged the central government to depose Hilmi, which it did on 8 June. He was replaced by the equally-resistant Shefik, whom Reshid also tried to depose. The cooperative Ibrahim Bedri was appointed as an official and Reshid used him to carry out his orders, bypassing Shefik. Reshid also replaced Midyat governor Nuri Bey with the hardline Edib Bey in July 1915, after Nuri refused to cooperate with Reshid.

On the night of 26 May, militiamen were caught attempting to plant arms in a Syriac Catholic church in Mardin. Their intent was to cite the supposed discovery of an arms cache as evidence of a Christian rebellion to justify the planned massacres. Mardin's well-to-do Christians were deported in convoys, the first of which left the city on 10 June. Those who refused to convert to Islam were murdered on the road to Diyarbekir. Half of the second convoy, which departed on 12 June, had been massacred before messengers from Diyarbekir announced that the non-Armenians had been pardoned by the sultan; they were subsequently freed. Other convoys from Mardin were targeted for extermination from late June until October. The city's Syriac Orthodox made a deal with authorities and were spared, but the other Christian denominations were decimated.

All Christian denominations were treated the same in the Mardin district countryside. Militia and Kurds attacked the village of Tell Ermen

Tell may refer to:

*Tell (archaeology), a type of archaeological site

* Tell (name), a name used as a given name and a surname

*Tell (poker), a subconscious behavior that can betray information to an observant opponent

Arts, entertainment, and ...

on 1 July, killing men, women, and children indiscriminately in the church after raping the women. The next day, more than 1,000 Syriac Orthodox and Catholics were massacred in Eqsor by militia and Kurds from the Milli, Deşi, Mişkiye, and Helecan tribes. Looting continued for several days before the village was burned down (which could be seen from Mardin). In Nusaybin, Talaat's order to spare the Syriacs was ignored as Christians of all denominations (including many Syriac Orthodox Church members) were arrested in mid-August and murdered in a ravine. In Djezire (Cizre) ''kaza'', Syriac Orthodox leader Gabro Khaddo cooperated with the authorities, defused plans for armed resistance, and paid a large ransom in June 1915; almost all Syriacs were killed with the ''kaza'' Armenians at the end of August. Some Armenian and Syriac Orthodox men were drafted to work in road construction or harvesting crops in place of those who had been killed. In August 1915, the harvest was over; the Armenians were killed, and the Syriacs were released.

Tur Abdin

Midyat

Midyat ( ku, Midyad, Syriac: аÐïÐùÐï ''M√´·∏èya·∏è'', Turoyo: ''Mi·∏èyoyo'', ar, ŸÖÿØŸäÿßÿ™) is a town in the Mardin Province of Turkey. The ancient city is the center of a centuries-old Hurrian town in Upper Mesopotamia. In its long history, the ...

considered resistance after hearing about massacres elsewhere, but the local Syriac Orthodox community initially refused to support this. On 21 June, 100 men (mostly Armenians and Protestants) were arrested, tortured for confessions implicating others, and executed outside the city; this panicked the Syriac Orthodox. Local people refused to hand over their arms, attacked government offices, and cut telegraph lines; local Arab and Kurdish tribes were recruited to attack the Christians. The town was pacified in early August after weeks of bloody urban warfare which killed hundreds of Christians. Survivors fled east to the more-defensible Iwardo, which held out successfully with the food aid of local Yazidis.

In June 1915, many Syriacs from Midyat ''kaza'' were massacred; others fled to the hills. A month earlier, local tribes and the Ramans began attacking Christian villages near Azakh (present-day İdil

ƒ∞dil ( syr, ÐêÐôÐü, Azakh, or ''Beth Zabday'', ku, Hezex, ar, ÿ¢ÿ≤ÿÆ, Azekh) is a city and district in ≈ûƒ±rnak Province in southeastern Turkey. It is located in the historical region of Tur Abdin.

In the city, there is a Syriac Orthodox C ...

) on the road from Midyat to Djezire. Survivors fled to Azakh, since it was defensible. The villages were attacked from north to south, giving the attackers at Azakh (one of the southernmost villages) more time to prepare. The primarily Syriac Orthodox village refused to hand over Catholics and Protestants, as demanded by the authorities. Azakh was first attacked on 17 or 18 August, but the defenders repelled this and subsequent attacks over the next three weeks.

Against the advice of General Mahmud K√¢mil Pasha

Mahmud Kâmil Pasha (1880 – June 1922) was a general of the Ottoman Army. He was born in Heleb (Aleppo) and died in Istanbul.

Career

On 22 December 1914, he was appointed as the commander of the Second Army. On 17 February 1915, he was appo ...

, Enver ordered the rebellion suppressed in November. Parts of the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1‚ÅÑ60 of a ''second'', or 1‚ÅÑ3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

, Fourth, and Sixth Armies and a Turkish–German expeditionary force under Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter and Ömer Naji were sent to crush the rebels, the latter diverted from attacking Tabriz. To justify the attack on Azakh, Ottoman officials claimed (with no evidence) that "Armenian rebels" had "cruelly massacred the Muslim population of the region". Scheubner, skeptical of the attack, forbade any Germans from participating. German general Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz and the German ambassador in Constantinople, Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

, informed Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg of the Ottoman request for German assistance in crushing the resistance. The Germans refused, fearing that the Ottomans would insinuate that the Germans initiated the anti-Christian atrocities. The defenders launched a surprise attack on Ottoman troops during the night of November 13–14, which led to a truce (lobbied by the Germans) which ended the resistance on favorable terms for the villagers. On 25 December 1915, the Ottoman government decreed that "instead of deporting all of the Syriac people", they were to be confined "in their present locations". Most of Tur Abdin was in ruins by this time, except for villages which resisted and families who found refuge in monasteries. Other Syriacs had fled south, into present-day Syria and Iraq.

Aftermath

Ethnic violence in Azerbaijan

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

dimmed prospects of a return to Hakkari. About 5,000 Assyrian and Armenian militia policed the area, but they frequently abused their power and killed Muslims without provocation.

From February to July 1918, the region was engulfed by ethnic violence. On 22 February, local Muslims and the Persian governor began an uprising against the Christian militias in Urmia. The better-organized Christians, led by Agha Petros, brutally crushed the uprising; hundreds (possibly thousands) were killed. On 16 March, Mar Shimun and many of his bodyguards were killed by the Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak, probably at the instigation of Persian officials fearing Assyrian separatism, after they met to discuss an alliance. Assyrians went on a killing and looting spree; unable to find Simko, they murdered Persian officials and inhabitants. The Kurds responded by massacring Christians, regardless of denomination or ethnicity. Christians were massacred in Salmas in June and in Urmia in early July, and many Assyrian women were abducted.

Christian militias in Azerbaijan were no match for the Ottoman army when it invaded in July 1918. Tens of thousands of Ottoman and Persian Assyrians fled south to Hamadan, where the British Dunsterforce was garrisoned, on 18 July to escape Ottoman forces approaching Urmia under Ali İhsan Sâbis

Ali İhsan Sâbis (1882 – 9 December 1957) was the commander for the Sixth Army of the Ottoman Empire during World War I. After the war he was exiled to Malta by the British occupation forces. After returning to Turkey, he was appointed to t ...

. The Ottoman invasion was followed by killings of Christians, including Chaldean archbishop Toma Audo, and the sacking of Urmia. Some remained in Persia, but there was another anti-Christian massacre on 24 May 1919. Historian Florence Hellot-Bellier says that the interethnic violence of 1918 and 1919 "demonstrate the degree of violence and resentment which had accumulated throughout all of these years of war and the break-up of the long-standing links between the inhabitants of the Urmia region". According to Gaunt, Assyrian "victims, when given the chance, turned without hesitation into perpetrators".

Exile in Iraq

During the journey to Hamadan, the Assyrians were harassed by Kurdish irregulars (probably at the instigation of Simko and

During the journey to Hamadan, the Assyrians were harassed by Kurdish irregulars (probably at the instigation of Simko and Sayyid Taha

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, sons of Muhammad' ...

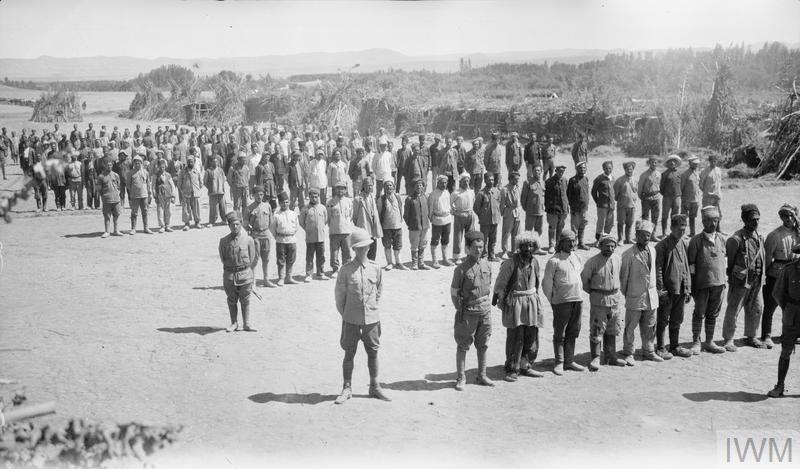

); some died of exhaustion. Many were killed near Heydarabad, and another 5,000 during an ambush by Ottoman forces and Kurdish irregulars near the Sahin Ghal'e mountain pass. Dependent on the British for protection, they were resettled in a refugee camp in Baqubah (near Baghdad) which held fifteen thousand Armenians and thirty-five thousand Assyrians in October 1918. Conditions at the camp were poor, and an estimated 7,000 Assyrians died there. Although the United Kingdom requested that Assyrian refugees be allowed to return, the Persian government refused.

In 1920, the camp in Baqubah was shut down and Assyrians hoping to return to Azerbaijan or Hakkari were sent northwards to Midan. About 4,500 Assyrians were resettled near Duhok

Duhok ( ku, ÿØŸá€Ü⁄©, translit=Dihok; ar, ÿØŸáŸàŸÉ, Dah≈´k; syr, ÐíÐùШ ТÐòÐóÐïЙÐê, Beth Nohadra) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It's the capital city of Duhok Governorate.

History

The city's origin dates back to the Stone ...

and Akre in northern Iraq. They worked as soldiers for the British rulers of Mandatory Iraq

The Kingdom of Iraq under British Administration, or Mandatory Iraq ( ar, الانتداب البريطاني على العراق '), was created in 1921, following the 1920 Iraqi Revolt against the proposed British Mandate of Mesopotamia, an ...

, which backfired when the British did not follow through with their repeated promises to resettle Assyrians in areas where they would be safer. After the end of the mandate, Assyrians were killed in the 1933 Simele massacre. After the massacre, France allowed 24,000 to 25,000 Assyrians to resettle along the Khabur in northeastern Syria. Other Assyrians were exiled in the Caucasus, Russia, or Lebanon, and a few emigrated to the United States, Canada, South America, and Europe.

Assyrians in Turkey

A few thousand Assyrians remained in Hakkari after 1915, and others returned after the war. Armed by the British, Agha Petros led a group of Assyrians from Tyari and Tkhuma who wanted to return in 1920; he was repulsed by Barwari chieftain Rashid Bek and the Turkish army. The remaining Assyrians were driven out again in 1924 by a Turkish army commanded by Kazim Karabekir, and the mountains were depopulated. In Siirt, Islamicized Syriacs (primarily women) were left behind; theirKurdified

Kurdification is a cultural change in which people, territory, or language become Kurdish. This can happen both naturally (as in Turkish Kurdistan) or as a deliberate government policy (as in Iraq after the 2003 invasion or in Syria after Syria ...

(or Arabized) descendants still live there. The survivors lost access to their property, becoming landless agricultural laborers or (later) an urban underclass. The depopulated Christian villages were resettled by Kurds or Muslims from the Caucasus. During and after the genocide, more than 150 churches and monasteries were demolished; others were converted to mosques or other uses, and many manuscripts and cultural objects were destroyed.

After 1923, local politicians went on an anti-Christian campaign which negatively impacted the Syriac communities (such as Adana, Urfa or Adiyaman) unaffected by the 1915 genocide. Many were forced to abandon their property and flee to Syria, eventually settling in Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, Qamishli, or the Khabur region. Despite its effort to court the Turkish nationalists, including denying that Syriac Orthodox had been persecuted during the war, the Syriac Orthodox patriarchate was expelled from Turkey in 1924. Unlike the Armenians, Jews, and Greeks, Assyrians were not recognized as a minority group in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

. The remaining population lived in submission to Kurdish aghas

Agha ( tr, ağa; ota, آغا; fa, آقا, āghā; "chief, master, lord") is an honorific title for a civilian or officer, or often part of such title. In the Ottoman times, some court functionaries and leaders of organizations like bazaar or ...

, subject to harassment and abuse which drove them to emigrate. Turkish laws denaturalized

Denaturalization is the loss of citizenship against the will of the person concerned. Denaturalization is often applied to ethnic minorities and political dissidents. Denaturalization can be a penalty for actions considered criminal by the state ...

those who had fled and confiscated their property. Despite their citizenship rights, many Assyrians who remained in Turkey had to re-purchase their property from Kurdish aghas or risk losing their Turkish citizenship. A substantial number of Assyrians continued to live in Tur Abdin until the 1980s. Some scholars have described the ongoing exclusion and harassment of Assyrians in Turkey as a continuation of the Sayfo.

Paris Peace Conference

In 1919, Assyrians attended the

In 1919, Assyrians attended the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

and attempted to lobby for compensation for their war losses. Although it has been labeled "the Assyrian delegation" in historiography, it was neither an official delegation nor a cohesive entity. Many attendees demanded monetary reparations for their war losses and an independent state, and all emphasized that Assyrians could not live under Muslim rule. Territory claimed by the Assyrians included parts of present-day Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. Although there was considerable sympathy for the Assyrians, none of their demands were met. The British and the French had other plans for the Middle East, and the rising Turkish nationalist movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

was also an obstacle. The Assyrians recalled that the British had promised them an independent country in exchange for their support, although it is disputed if such a promise was ever made; many Assyrians felt betrayed that this desire was not fulfilled.

Historiography