Senecas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Seneca ( ; ) are a group of Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of

Primitive Archer

Volume 18 (4). February–March 2010. pp. 16–199.

The Iroquois were involved in numerous other battles during the American Revolution. Notable raids like the Cherry Valley massacre and Battle of Minisink, were carefully planned raids on a trail laid out "from the Susquehanna to the Delaware Valley and over the Pine Hill to the Esopus Country". In 1778 Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk warriors conducted raids on white settlements in the upper Susquehanna Valley. Although the Iroquois were active participants, Seneca like Governor Blacksnake were extremely fed up with the brutality of the war. He noted particularly on his behavior at Oriskany, and how he felt "it was great sinfull by the sight of God".

Warriors like Blacksnake were feeling the mental toll of killing so many people during the American Revolution. As Raphael noted in his book, "warfare had been much more personal" for the Iroquois before the American Revolution. During the revolution, these once proud Iroquois were now reduced to conducting brutal acts such as the killing of women and children at the Cherry Valley massacre and the clubbing of surviving American soldiers at Oriskany. Although Seneca like Governor Blacksnake felt sorrow for their brutal actions, the Americans responded in a colder and more brutal fashion. This retaliation came in the Sullivan Expedition.

The planning of the Sullivan Expedition began in 1778 as a way to respond to the Iroquois victories and massacres. This plan came about from the complaints of New Yorkers at the Continental Congress. The New Yorkers had suffered from the massive Iroquois offensives from 1777 to 1778, and they wanted revenge. Besides the brutal battles described previously, the New Yorkers were especially concerned with Joseph Brant. Joseph Brant had Mohawk parents and British lineage, and at a young age, he was taken under the superintendent for Indian affairs.

Brant grew to be a courteous and well-spoken man, and he took up the fight for the British because of harassment and discrimination from the Americans during the lead-up to the American Revolution. Thus, Brant formed a military group known as Brant's Volunteers, which consisted of Mohawks and Loyalists. Brant and his band of volunteers led many raids against hamlets and farms in New York, especially Tryon County. As a result of Brant's exploits, the Iroquois offensives, and several massacres the Iroquois inflicted against colonial towns, in 1778 the Seneca and other western nations were attacked by United States forces as part of the Sullivan Expedition.

The Iroquois were involved in numerous other battles during the American Revolution. Notable raids like the Cherry Valley massacre and Battle of Minisink, were carefully planned raids on a trail laid out "from the Susquehanna to the Delaware Valley and over the Pine Hill to the Esopus Country". In 1778 Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk warriors conducted raids on white settlements in the upper Susquehanna Valley. Although the Iroquois were active participants, Seneca like Governor Blacksnake were extremely fed up with the brutality of the war. He noted particularly on his behavior at Oriskany, and how he felt "it was great sinfull by the sight of God".

Warriors like Blacksnake were feeling the mental toll of killing so many people during the American Revolution. As Raphael noted in his book, "warfare had been much more personal" for the Iroquois before the American Revolution. During the revolution, these once proud Iroquois were now reduced to conducting brutal acts such as the killing of women and children at the Cherry Valley massacre and the clubbing of surviving American soldiers at Oriskany. Although Seneca like Governor Blacksnake felt sorrow for their brutal actions, the Americans responded in a colder and more brutal fashion. This retaliation came in the Sullivan Expedition.

The planning of the Sullivan Expedition began in 1778 as a way to respond to the Iroquois victories and massacres. This plan came about from the complaints of New Yorkers at the Continental Congress. The New Yorkers had suffered from the massive Iroquois offensives from 1777 to 1778, and they wanted revenge. Besides the brutal battles described previously, the New Yorkers were especially concerned with Joseph Brant. Joseph Brant had Mohawk parents and British lineage, and at a young age, he was taken under the superintendent for Indian affairs.

Brant grew to be a courteous and well-spoken man, and he took up the fight for the British because of harassment and discrimination from the Americans during the lead-up to the American Revolution. Thus, Brant formed a military group known as Brant's Volunteers, which consisted of Mohawks and Loyalists. Brant and his band of volunteers led many raids against hamlets and farms in New York, especially Tryon County. As a result of Brant's exploits, the Iroquois offensives, and several massacres the Iroquois inflicted against colonial towns, in 1778 the Seneca and other western nations were attacked by United States forces as part of the Sullivan Expedition.

Smokes cheap, tensions high

(Also titled

Portrait of a Failed American City

") ''Pittsburgh Tribune-Review''. Retrieved July 28, 2012. Then, in the early 2000s issues re-arose over Seneca use of settlement lands to establish casino gaming operations, which have generated considerable revenues for many tribes since the late 20th century.

''Salamanca Press''. The Seneca were given five days to respond or to face fines and a forced shutdown. They said they refuse to comply with the commission's order and will appeal. Given the declining economic situation because of a nationwide recession, in summer 2008 the Seneca halted construction on the new casino in Buffalo. In December 2008 they laid off 210 employees from the three casinos.

Seneca Indian Collections

A bibliography, with links where available, from the Buffalo History Museum.

Seneca Allegany Casino

Seneca Niagara Casino

Seneca Gaming Corporation

How the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign Dispossessed the Seneca

{{DEFAULTSORT:Seneca People Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands Iroquois Iroquoian peoples Native American history of New York (state) Native American tribes in New York (state) Native American tribes in Oklahoma First Nations in Ontario Native American tribes in Pennsylvania Native American people in the American Revolution

Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The Canada–United Sta ...

, one of the five Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. Their nation was the farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois League ( Haudenosaunee) in New York before the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. For this reason, they are called “The Keepers of the Western Door.”

In the 21st century, more than 10,000 Seneca live in the United States, which has three federally recognized Seneca tribes. Two of them are centered in New York: the Seneca Nation of Indians, with five territories in western New York near Buffalo; and the Tonawanda Seneca Nation. The Seneca-Cayuga Nation is in Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, where their ancestors were relocated from Ohio during the Indian Removal. Approximately 1,000 Seneca live in Canada, near Brantford, Ontario

Brantford (Canada 2021 Census, 2021 population: 104,688) is a city in Ontario, Canada, founded on the Grand River (Ontario), Grand River in Southwestern Ontario. It is surrounded by County of Brant, Brant County but is politically separate wi ...

, at the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation. They are descendants of Seneca who resettled there after the American Revolution, as they had been allies of the British and forced to cede much of their lands.

Name

The Seneca's own name for themselves is ''Onöndowa'ga: or ''O-non-dowa-gah'', meaning "Great Hill People" Theexonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

''Seneca'' is "the Anglicized form of the Dutch pronunciation of the Mohegan rendering of the Iroquoian ethnic appellative" originally referring to the Oneida. The Dutch applied the name ''Sennecaas'' promiscuously to the four westernmost nations, the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, but with increasing contact the name came to be applied only to the latter. The French called them ''Sonontouans''. The Dutch name is also often spelled ''Sinnikins'' or ''Sinnekars'', which was later corrupted to Senecas.

History

Senecaoral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information from

people, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people who pa ...

states that the tribe originated in a village called Nundawao, near the south end of Canandaigua Lake, at South Hill. Close to South Hill stands the Bare Hill, known to the Seneca as . Bare Hill is part of the Bare Hill Unique Area, which began to be acquired by the state in 1989. Bare Hill had been the site of a Seneca (or Seneca-ancestral people) fort.

The first written reference to this fort was made in 1825 by the Tuscarora historian David Cusick in his history of the Seneca Indians.

In the early 1920s, the material that made up the Bare Hill fort was used by the Town of Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

highway department for road fill.

The Seneca historically lived in what is now New York state between the Genesee River

The Genesee River ( ) is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Roch ...

and Canandaigua Lake. The dating of an oral tradition mentioning a solar eclipse yields 1142 AD as the year for the Seneca joining the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

(Haudenosaunee). Some recent archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

evidence indicates their territory eventually extended to the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

in present-day northwestern Pennsylvania, particularly after the Iroquois destroyed both the Wenrohronon and Erie nations in the 17th century, who were native to the area. The Seneca were by far the most populous of the Haudenosaunee nations, numbering about four thousand by the seventeenth century.

Seneca villages were located as far east as current-day Schuyler County (e.g. Catherine's Town and Kanadaseaga), south into current Tioga and Chemung counties, north and east into Tompkins and Cayuga counties, and west into the Genesee River

The Genesee River ( ) is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Roch ...

valley. The villages were the homes and headquarters of the Seneca. While the Seneca maintained substantial permanent settlements and raised agricultural crops in the vicinity of their villages, they also hunted widely through extensive areas. They also executed far-reaching military campaigns. The villages, where hunting and military campaigns were planned and executed, indicate the Seneca had hegemony in these areas.

Major Seneca villages were protected with wooden palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a row of closely placed, high vertical standing tree trunks or wooden or iron stakes used as a fence for enclosure or as a defensive wall. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymo ...

s. Ganondagan, with 150 longhouses, was the largest Seneca village of the 17th century, while Chenussio, with 130 longhouses, was a major village of the 18th century.

The Seneca nation has two branches: the western and the eastern. Each branch was individually incorporated and recognized by the Iroquois Confederacy Council. The western Seneca lived predominantly in and around the Genesee River

The Genesee River ( ) is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Roch ...

, gradually moving west and southwest along Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

and the Niagara River, then south along the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

into Pennsylvania. The eastern Seneca lived predominantly south of Seneca Lake. They moved south and east into Pennsylvania and the western Catskill area.Parker, Arthur. ''The History of the Seneca Indians''. Ira J. Freidman (1967); Empire State Historical Publications Series, XLIII, p. 13–20.

The west and north were under constant attack from their powerful Iroquoian brethren, the Huron (Wyandot) To the South, the Iroquoian-speaking tribes of the Susquehannock (Conestoga) also threatened constant warfare. The Algonquian tribes of the Mohican blocked access to the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

in the east and northeast. In the southeast, the Algonkian tribes of the Lenape people (Delaware, Minnisink and Esopus) threatened war from eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and the Lower Hudson.

The Seneca used the Genesee and Allegheny rivers, as well as the Great Indian War and Trading Path (the Seneca Trail), to travel from southern Lake Ontario into Pennsylvania and Ohio (Merrill, Arch. ''Land of the Senecas''; Empire State Books, 1949, pp. 18–25). The eastern Seneca had territory just north of the intersection of the Chemung, Susquehanna, Tioga and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

rivers, which converged in Tioga. The rivers provided passage deep into all parts of eastern and western Pennsylvania, as well as east and northeast into the Delaware Water Gap and the western Catskills. The men of both branches of the Seneca wore the same headgear. Like the other Haudenosaunee, they wore hats with dried cornhusks on top. The Seneca wore theirs with one feather sticking up straight.

Traditionally, the Seneca Nation's economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

was based on hunting and gathering activities, fishing, and the cultivation of varieties of corn

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout Poaceae, grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago ...

, bean

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are traditi ...

s, and squash. These vegetables were the staple of the Haudenosaunee diet and were called "the three sisters" (työhe'hköh). Seneca women generally grew and harvested varieties of the three sisters, as well as gathering and processing medicinal plants, roots, berries, nuts, and fruit. Seneca women held sole ownership of all the land and the homes. The women also tended to any domesticated animals such as dogs and turkeys.

Seneca men were generally in charge of locating and developing the town sites, including clearing the forest for the production of fields. Seneca men also spent a great deal of time hunting and fishing. This activity took them away from the towns or villages to well-known and productive hunting and fishing grounds for extended amounts of time. These hunting and fishing locations were altered and well maintained to encourage game; they were not simply "wild" lands. Seneca men maintained the traditional title of war sachems within the Haudenosaunee. A Seneca war sachem was in charge of gathering the warriors and leading them into battle.

Seneca people lived in villages and towns. Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

excavations indicate that some of these villages were surrounded by palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a row of closely placed, high vertical standing tree trunks or wooden or iron stakes used as a fence for enclosure or as a defensive wall. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymo ...

s because of warfare. These towns were relocated every ten to twenty years as soil, game and other resources were depleted. During the nineteenth century, many Seneca adopted customs of their immediate American neighbors by building log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a minimally finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first-generation home building by settl ...

s, practicing Christianity, and participating in the local agricultural economy.

Daily life of the Seneca

The Seneca traditionally lived inlonghouse

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from lumber, timber and ...

s, which are large buildings that were up to 100 feet long and approximately 20 feet wide. The longhouses were shared among related families and could hold up to 60 people. Hearths were located in the central aisle, and two families shared a hearth. Over time they began to build cabins, similar to those of their American neighbors.

The main form of social organization is the clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

, or , nominally each descended from one woman. The Seneca have eight clans: Bear (), Wolf (), Turtle (), Beaver( ), Deer (), Hawk (), Snipe (), and Heron (). The clans are divided into two ''sides'' ( moieties)the Bear, Wolf, Turtle, and Beaver are the ''animal'' side, and the Deer, Hawk, Snipe, and Heron are the ''bird'' side.

The Iroquois have a matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

kinship system; inheritance and property descend through the maternal line. Women are in charge of the clans. Children are considered born into their mother's clan and take their social status from her family. Their mother's eldest brother was traditionally more of a major figure in their lives than their biological father, who does not belong to their clan. The presiding elder of a clan is called the "clan mother". Despite the prominent position of women in Iroquois society, their influence on the diplomacy of the nation was limited. If the "clan mothers" do not agree with any major decisions made by the chiefs, they can eventually depose them.

Seneca Archery

Arrows from the area are made from split hickory, although shoots of dogwood and Viburnum were used as well. The eastern two feather style offletching

Fletching is the fin-shaped aerodynamic stabilization device attached on arrows, crossbow bolts, Dart (missile), darts, and javelins, typically made from light semi-flexible materials such as feathers or Bark (botany), bark. Each piece of such a ...

was used, although three radial feathers were also used.

The Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

has an example of a Seneca bow, which was donated 1908. It is made of unbacked hickory

Hickory is a common name for trees composing the genus ''Carya'', which includes 19 species accepted by ''Plants of the World Online''.

Seven species are native to southeast Asia in China, Indochina, and northeastern India (Assam), and twelve ...

, and is tip to tip. Although the string is missing for the specimen, when strung it would make a good "D" shape with slightly recurved tips, and was obviously made for bigger game. The tips are irregular in shape, which is typical from this region.Berger, Billy. 2010. "Treasures of the Smithsonian. Part IV. Archery of the Northeastern United States" Seneca and Pamunkey: Seneca.Primitive Archer

Volume 18 (4). February–March 2010. pp. 16–199.

Contact with Europeans

During the colonial period, the Seneca became involved in thefur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

, first with the Dutch and then with the British. This served to increase hostility with competing native groups, especially their traditional enemy, the Huron (Wyandot), an Iroquoian-speaking tribe located near Lac Toronto in New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

.

In 1609, the French allied with the Huron (Wyandot) and set out to destroy the Iroquois. The Iroquois-Huron war raged until approximately 1650. Led by the Seneca, the Confederacy began a near 35-year period of conquest over surrounding tribes following the defeat of its most powerful enemy, the Huron (Wyandot). The Confederacy conducted Mourning Wars to take captives to replace people lost in a severe smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

epidemic in 1635. Through raids, they stabilized their population after adopting young women and children as captives and incorporating them into the tribes. By the winter of 1648, the Confederacy, led by the Seneca, fought deep into Canada and surrounded the capital of Huronia. Weakened by population losses due to their own smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

epidemics

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of Host (biology), hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example ...

as well as warfare, the Huron (Wyandot) unconditionally surrendered. They pledged allegiance to the Seneca as their protector. The Seneca subjugated the Huron (Wyandot) survivors and sent them to assimilate in the Seneca homelands.

In 1650, the Seneca attacked and defeated the Neutrals to their west. In 1653, the Seneca attacked and defeated the Erie to their southwest. Survivors of both the Huron and Erie were subjugated to the Seneca and relocated to the Seneca homeland. The Seneca took over the vanquished tribe's traditional territories in western New York.

In 1675, the Seneca defeated the Andaste (Susquehannock) to the south and southeast. The Confederacy's hegemony extended along the frontier from Canada to Ohio, deep into Pennsylvania, along the Mohawk Valley and into the lower Hudson in the east. They sought peace with the Algonquian-speaking Mohegan (Mahican), who lived along the Hudson River. Within the Confederacy, Seneca power and presence extended from Canada to what would become Pittsburgh, east to the future Lackawanna and into the land of the Minnisink on the New York /New Jersey border.

The Seneca tried to curtail the encroachment of white settlers. This increased tensions and conflict with the French to the north and west, and the English and Dutch to the south and east. As buffers, the Confederacy resettled conquered tribes between them and the European settlers, with the greatest concentration of resettlements on the lower Susquehanna.

In 1685, King Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

of France sent Marquis de Denonville to govern New France in Quebec. Denonville set out to destroy the Seneca Nation and in 1687 landed a French armada with "the largest army North America had ever seen" at Irondequoit Bay. Denonville struck straight into the seat of Seneca power and destroyed many of its villages, including the Seneca's eastern capital of Ganondagan. Fleeing before the attack, the Seneca moved further west, east and south down the Susquehanna River. Although great damage was done to the Seneca homeland, the Seneca's military might was not appreciably weakened. The Confederacy and the Seneca moved into an alliance with the British in the east.

Senecas' expanding influence and diplomacy

In and around 1600, the area currently comprising Sullivan,Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

and Orange counties of New York was home to the Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

Indians, an Algonquian-speaking people whose territory extended deep along the coastal areas of the mid-Atlantic coast, up into present-day Connecticut. They occupied the western part of Long Island as well. The Lenape nation was Algonkian-speaking and made up of the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, Minnisink and Esopus bands, differentiated according to their territories. These bands later became known as the Munsee, based on their shared dialect. (Folts at pp 32) The Munsee inhabited large tracts of land from the middle Hudson into the Delaware Water Gap, and into northeast Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

and northwest New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. The Esopus inhabited the Mid-Hudson valley (Sullivan and Ulster counties). The Minnisink inhabited northwest New Jersey. The Delaware inhabited the southern Susquehanna and Delaware water gaps. The Minnisink-Esopus trail, today's Route 209, helped tie this world together.

To the west of the Delaware nation were the Iroquoian-speaking Andaste/ Susquehannock. To the east of the Delaware Nation lay the encroaching peoples of Dutch New Netherland. From Manhattan, up through the Hudson, the settlers were interested in trading furs with the Susquehannock occupying territory in and around current Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster ( ) is a city in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 58,039 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, eighth-most populous ci ...

. As early as 1626, the Susquehannock were struggling to get past the Delaware to trade with the Dutch in New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

(Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

). In 1634, war broke out between the Delaware and the Susquehannock, and by 1638, the defeated Delaware became tributaries to the Susquehanna.

The Iroquois Confederacy to the north was growing in strength and numbers, and the Seneca, as the most numerous and adventurous, began to travel extensively. Eastern Seneca traveled down the Chemung River to the Susquehanna River. At Tioga the Seneca had access to every corner of Munsee country. Seneca warriors traveled the Forbidden Path south to Tioga to the Great Warrior Path to Scranton and then east over the Minnisink Path through the Lorde's valley to Minisink. The Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

path went straight south through the ancient Indian towns of Cookhouse, Cochecton and Minnisink, where it became the Minsi Path.

Using these ancient highways, the Seneca exerted influence in what is today Ulster and Sullivan counties from the Dutch colonial era onward. Historical evidence demonstrating Seneca presence in the Lower Catskills includes:

In 1657 and 1658, the Seneca visited, as diplomats, Dutch colonial officials in New Amsterdam.

In 1659 and 1660, the Seneca interceded in the First Esopus War, which was going on between the Dutch and Esopus at current-day Kingston. The Seneca chief urged Stuyvesant to end the bloodshed and "return the captured Esopus savages".

In 1675, after a decade of warfare between the Iroquois (mainly the Mohawk and Oneida) and the Andaste/Susquehannock, the Seneca finally succeeded in vanquishing their last remaining great enemy.(Parker at pp 49) Survivors were colonized in settlements along the Susquehanna River and were assimilated into the Seneca and Cayuga people.

In 1694, Captain Arent Schuyler, in an official report, described the Minnisink chiefs as being fearful of being attacked by the Seneca because of not paying wampum tribute to these Iroquois.

Around 1700, the upper Delaware watershed of New York and Pennsylvania became home of the Minnisink Indians moving north and northwest from New Jersey, and of Esopus Indians moving west from the Mid-Hudson valley.Folts at p. 34

By 1712, the Esopus Indians were reported to have reached the east Pepacton branch of the Delaware River, on the western slopes of the Catskill Mountains

The Catskill Mountains, also known as the Catskills, are a physiographic province and subrange of the larger Appalachian Mountains, located in southeastern New York. As a cultural and geographic region, the Catskills are generally defined a ...

.

From 1720 to the 1750s, the Seneca resettled and assimilated the Munsee into their people and the Confederacy. Historical accounts had noted the difficulties encountered by the Seneca during this period and noted a dissolution of their traditional society under pressure of disease and encroachment by European Americans. But fieldwork at the 1715–1754 Seneca Townley-Read site near Geneva, New York

Geneva is a City (New York), city in Ontario County, New York, Ontario and Seneca County, New York, Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake (New York), Seneca Lake; all land port ...

, has recovered evidence of "substantial Seneca autonomy, selectivity, innovation, and opportunism in an era usually considered to be one of cultural disintegration".Jordan, Kurt A. (2013). "Incorporation and Colonization: Postcolumbian Iroquois Satellite Communities and Processes of Indigenous Autonomy," ''American Anthropologist'' 115 (1) In 1756, the Confederacy directed the Munsee to settle in a new satellite town in Seneca territory called Assinisink (where Corning developed) on the Chemung River. In this period, they developed satellite towns for war captives who were being assimilated near several of their major towns. The Seneca received some of the Munsee's war prisoners as part of their negotiations.

At a peace conference in Easton, Pennsylvania in 1758, the Seneca chief Tagashata required the Munsee and Minnisink to conclude a peace with the colonists and "take the hatchet out of your heads, and bury it under ground, where it shall always rest and never be taken up again". A large delegation of Iroquois attended this meeting to demonstrate that the Munsee were under their protection.Herbert C. Kraft, ''The Lenape: Archaeology, History and Ethnography'' (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1986), p. 230.

In 1759, as colonial records indicate, negotiators had to go through the Seneca in order to have diplomatic success with the Munsee.

Despite the French military campaigns, Seneca power remained far-reaching at the beginning of the 18th century. Gradually, the Seneca began to ally with their trading partners, the Dutch and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, against France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

's ambitions in the New World. By 1760 during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, they helped the British capture Fort Niagara from the French. The Seneca had relative peace from 1760 to 1775. In 1763 a Seneca war party ambushed a British supply train and soldiers in Battle of Devil's Hole, also known as the Devil's Hole massacre, during Pontiac's Rebellion.

After the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

broke out between the British and the colonists, the Seneca at first attempted to remain neutral but both sides tried to bring them into the action. When the rebel colonists defeated the British at Fort Stanwix, they killed many Seneca onlookers.

Interactions with the United States

Pre-American Revolution Involvement

The Seneca Tribe before the American Revolution had a prosperous society. The Iroquois Confederacy had ended the fighting amongst the war-based Iroquois tribes and allowed them to live in peace with each other. Yet, despite this peace amongst themselves, the Iroquois tribes were all revered as fierce warriors and were reputed to control together a large empire that stretched hundreds of miles along the Appalachian Mountains. The Seneca were a part of this confederacy with the Cayuga, Onondagas, Oneidas, Mohawks, and, later on, the Tuscaroras. However, although the Seneca and Iroquois tribes had ceased fighting each other, they still continued to conduct raids on outsiders, or rather their European visitors. Despite the Iroquois continuing raids on their new European neighbors, the Iroquois tribes struck up profitable relationships with the Europeans, especially the English. In 1677, the English were able to make an alliance with the Iroquois league called the "Covenant Chain". In 1768, the English renewed this alliance when Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. This treaty put the British in good favor with the Iroquois, as they felt that the British had their best interests in mind as well. The Americans, unlike the British, were disliked by the Seneca because of their continual disregard for the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Specifically, the Iroquois were enraged by the Americans movement into the Ohio Territory. However, despite their continual encroachment on established Iroquois land, the Americans respected their skills at warfare and attempted to exclude them from their conflict with the British. The Americans viewed their conflict with the British as a conflict meant to include only them. The Albany Council occurred in August, and the Iroquois Confederacy debated about the Revolution from August 25 to August 31. The non-Iroquois present at the council consisted of important figures likePhilip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 20, 1733 - November 18, 1804) was an American general in the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New York. He is usually known as ...

, Oliver Wolcott, Turbutt Francis, Volkert Douw, Samuel Kirkland

Samuel Kirkland (December 1, 1741 – February 28, 1808) was a Presbyterian minister and missionary among the Oneida and Tuscarora peoples of central New York State. He was a long-time friend of the Oneida chief Skenandoa.

Kirkland graduated ...

, and James Dean. The Iroquois at the council were representatives from all the tribes, but the Mohawk, Oneidas, and Tuscaroras had the most representatives. The Iroquois agreed with the Americans and decided at their Albany Council that they should remain as spectators to the conflict. A Mohawk Chief named Little Abraham declared that "the determination of the Six Nations not to take any part; but as it is a family affair, to sit still and see you fight it out". Thus, the Iroquois chose to remain neutral for the time being. They felt it would be best to stand aside while the Colonists and the British battled. They did not wish to get caught up in this supposed "family quarrel between hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the ga ...

and Old England".

Despite this neutrality, the anti-Native American rhetoric of the Americans pushed the Iroquois over to the side of the British. The Americans put forth an extremely racist and divisive message. They viewed the Iroquois and other Native Americans as savages and lesser people. An example of this rhetoric came in the Declaration of Independence: "the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions." As a result of this terrible rhetoric, many Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca prepared to join the British. However, many Oneida and Tuscarora were able to be swayed by an American missionary, Samuel Kirkland

Samuel Kirkland (December 1, 1741 – February 28, 1808) was a Presbyterian minister and missionary among the Oneida and Tuscarora peoples of central New York State. He was a long-time friend of the Oneida chief Skenandoa.

Kirkland graduated ...

. The Iroquois nation began to divide as the Revolution continued and, as a result, they extinguished the council fire that united the six Iroquois nations, therefore ending the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois ended their political unity during the most turbulent time in their history. Two powers in the midst of battle pulled them apart to gain their skill as warriors. This divided the Iroquois and the tribes chose sides based on preference.

In addition to the push of American bigoted rhetoric, the British also continued to attempt to sway the Iroquois towards their side. One British attempt to sway the Iroquois was described by two Seneca tribesmen, Mary Jemison and Governor Blacksnake. They both described the grandeur of the lavish gifts that the British bestowed upon the Iroquois. Governor Blacksnake's account held many details about the luxurious treatment that they received from the British: " mediately after arrival the officers came to see us to See what wanted for to Support the Indians with Provisions and with the flood of Rum. they are Some of the ... warriors made use of this intoxicating Drinks, there was several Barrel Delivered to us for us to Drinked for the white man told us to Drinked as much as we want of it all free gratus, and the goods if any of us wishes to get for our own use." Contingent to this generosity was the loyalty of the Iroquois to the British. The Iroquois debated whether to side with the British or not. An argument to remain neutral until further development came from Governor Blacksnake's uncle Cornplanter, but Joseph Brant twisted his recommendation to wait as a sign of cowardice. The British noticed that the Indian warriors were divided on the issue, so the British presented them with rum, bells, ostrich feathers, and a covenant belt. The Americans attempted a similar wine and dine method on the Tuscarora and Oneidas. In the end, the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca sided with the British, and the Tuscarora and Oneida sided with the Americans. From this point on, the Iroquois would have a serious role in the American Revolution. The war divided them and now they would be fighting against each other from 1777 till the end on opposite sides.

Involvement in the American Revolution

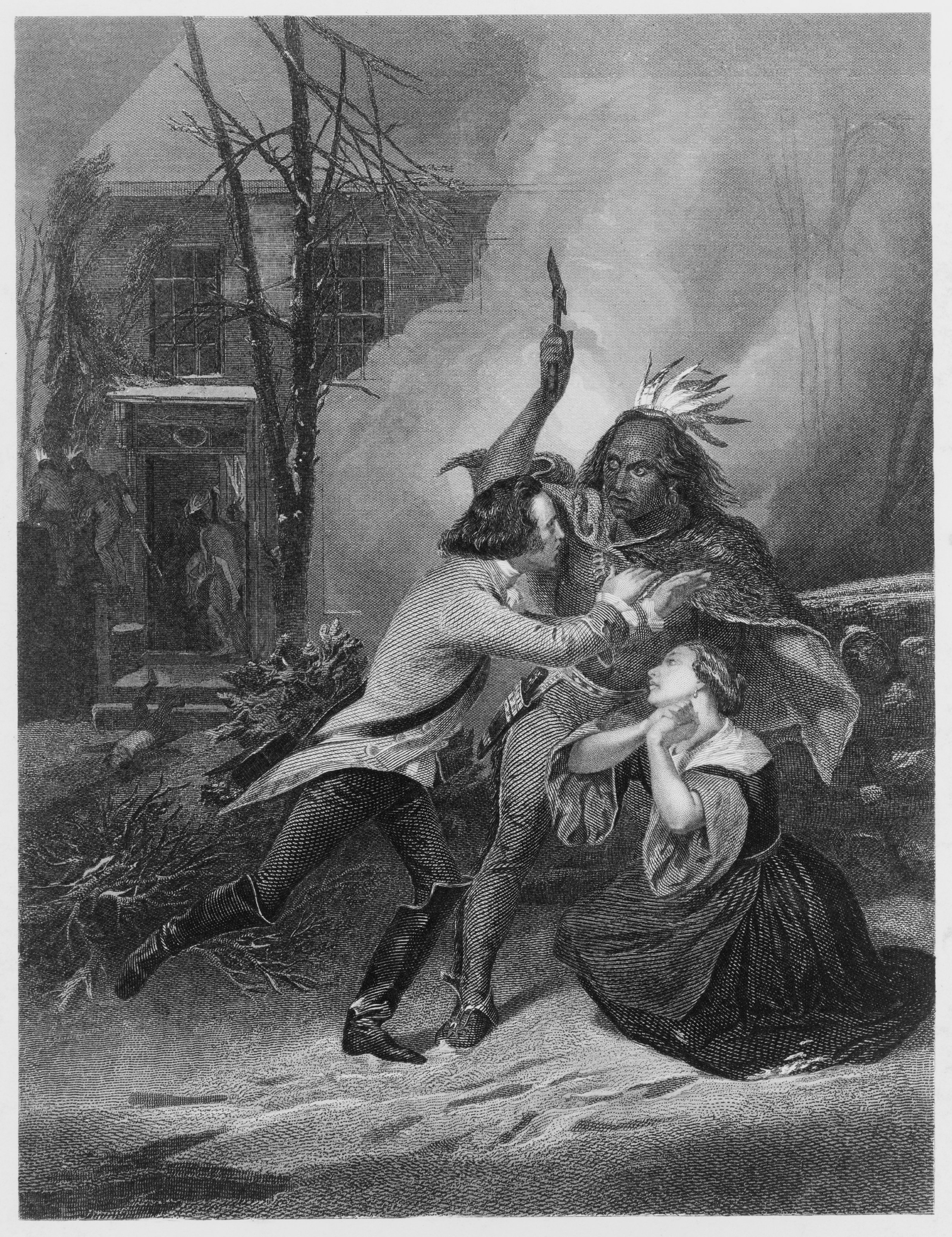

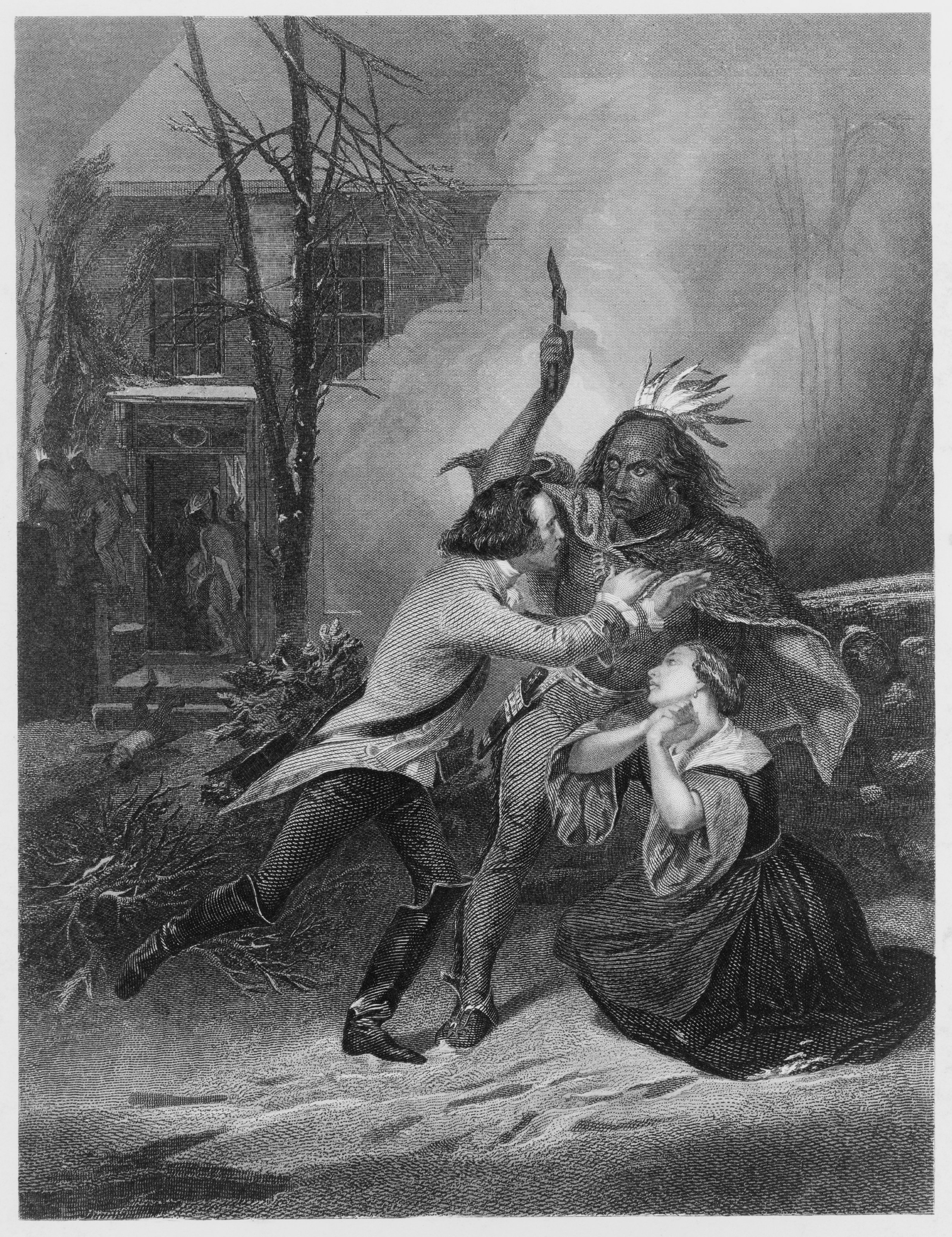

The Seneca chose to side with the British in the American Revolution. One of the earliest battles the Iroquois were involved in occurred on August 6, 1777, in Oriskany During the Battle of Oriskany, Native Americans led a brutal attack against the rebel Americans where they "killed, wounded, or captured the majority of patriot soldiers". The Seneca Governor Blacksnake described the battle from the viewpoint of the victorious Indians: "as we approach to a firghting we had preparate to make one fire and Run amongst them we So, while we Doing it, feels no more to Kill the Beast, and killed most all, the americans army, only a few white man Escape from us ... there I have Seen the most Dead Bodies all it over that I neve Did see." Author Ray Raphael made a connection between the Seneca warriors and Continental Army soldiers by noting that Blacksnake "was not unlike" known Revolutionary veterans " Joseph Plumb Martin and James Collins and other white American eteranswho could never finally resolve whether killing was right or wrong". As the war went on, many more brutal attacks and atrocities would be committed by both sides, notably the Sullivan Expedition, which devastated Iroquois and Seneca lands. The Iroquois were involved in numerous other battles during the American Revolution. Notable raids like the Cherry Valley massacre and Battle of Minisink, were carefully planned raids on a trail laid out "from the Susquehanna to the Delaware Valley and over the Pine Hill to the Esopus Country". In 1778 Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk warriors conducted raids on white settlements in the upper Susquehanna Valley. Although the Iroquois were active participants, Seneca like Governor Blacksnake were extremely fed up with the brutality of the war. He noted particularly on his behavior at Oriskany, and how he felt "it was great sinfull by the sight of God".

Warriors like Blacksnake were feeling the mental toll of killing so many people during the American Revolution. As Raphael noted in his book, "warfare had been much more personal" for the Iroquois before the American Revolution. During the revolution, these once proud Iroquois were now reduced to conducting brutal acts such as the killing of women and children at the Cherry Valley massacre and the clubbing of surviving American soldiers at Oriskany. Although Seneca like Governor Blacksnake felt sorrow for their brutal actions, the Americans responded in a colder and more brutal fashion. This retaliation came in the Sullivan Expedition.

The planning of the Sullivan Expedition began in 1778 as a way to respond to the Iroquois victories and massacres. This plan came about from the complaints of New Yorkers at the Continental Congress. The New Yorkers had suffered from the massive Iroquois offensives from 1777 to 1778, and they wanted revenge. Besides the brutal battles described previously, the New Yorkers were especially concerned with Joseph Brant. Joseph Brant had Mohawk parents and British lineage, and at a young age, he was taken under the superintendent for Indian affairs.

Brant grew to be a courteous and well-spoken man, and he took up the fight for the British because of harassment and discrimination from the Americans during the lead-up to the American Revolution. Thus, Brant formed a military group known as Brant's Volunteers, which consisted of Mohawks and Loyalists. Brant and his band of volunteers led many raids against hamlets and farms in New York, especially Tryon County. As a result of Brant's exploits, the Iroquois offensives, and several massacres the Iroquois inflicted against colonial towns, in 1778 the Seneca and other western nations were attacked by United States forces as part of the Sullivan Expedition.

The Iroquois were involved in numerous other battles during the American Revolution. Notable raids like the Cherry Valley massacre and Battle of Minisink, were carefully planned raids on a trail laid out "from the Susquehanna to the Delaware Valley and over the Pine Hill to the Esopus Country". In 1778 Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk warriors conducted raids on white settlements in the upper Susquehanna Valley. Although the Iroquois were active participants, Seneca like Governor Blacksnake were extremely fed up with the brutality of the war. He noted particularly on his behavior at Oriskany, and how he felt "it was great sinfull by the sight of God".

Warriors like Blacksnake were feeling the mental toll of killing so many people during the American Revolution. As Raphael noted in his book, "warfare had been much more personal" for the Iroquois before the American Revolution. During the revolution, these once proud Iroquois were now reduced to conducting brutal acts such as the killing of women and children at the Cherry Valley massacre and the clubbing of surviving American soldiers at Oriskany. Although Seneca like Governor Blacksnake felt sorrow for their brutal actions, the Americans responded in a colder and more brutal fashion. This retaliation came in the Sullivan Expedition.

The planning of the Sullivan Expedition began in 1778 as a way to respond to the Iroquois victories and massacres. This plan came about from the complaints of New Yorkers at the Continental Congress. The New Yorkers had suffered from the massive Iroquois offensives from 1777 to 1778, and they wanted revenge. Besides the brutal battles described previously, the New Yorkers were especially concerned with Joseph Brant. Joseph Brant had Mohawk parents and British lineage, and at a young age, he was taken under the superintendent for Indian affairs.

Brant grew to be a courteous and well-spoken man, and he took up the fight for the British because of harassment and discrimination from the Americans during the lead-up to the American Revolution. Thus, Brant formed a military group known as Brant's Volunteers, which consisted of Mohawks and Loyalists. Brant and his band of volunteers led many raids against hamlets and farms in New York, especially Tryon County. As a result of Brant's exploits, the Iroquois offensives, and several massacres the Iroquois inflicted against colonial towns, in 1778 the Seneca and other western nations were attacked by United States forces as part of the Sullivan Expedition. George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

called upon Continental Army General John Sullivan (general) to lead this attack upon the Iroquois. He had received anywhere from 3000 to 4500 soldiers to fight the Iroquois.

Overall, the Sullivan Expedition wreaked untold havoc and destruction upon the Iroquois lands, as the soldiers "destroy dnot only the homes of the Iroquois but their food stocks as well". Seneca woman Mary Jemison recalled how the Continental soldiers "destroyed every article of the food kind that they could lay their hands on". To make matters worse for the Iroquois, an especially hard winter in 1780 caused additional suffering for the downtrodden Iroquois. The Sullivan Expedition highlighted a period of true total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all (including civilian-associated) resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilises all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare ov ...

within the American Revolution. The Americans looked to cripple the Iroquois. They accomplished that, but they instilled a deep hatred in the Iroquois warriors.

After the Sullivan Expedition the recovered Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk, angered by the destruction caused, resumed their raids on American settlements in New York. These Iroquois tribes not only attacked and plundered the American colonists, they also set fire to Oneida and Tuscarora settlements. The Iroquois continued their attacks upon the Americans, even after General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown in 1781. They did not stop until their allies had caved in and surrendered. In 1782, the Iroquois had finally stopped fighting when the British General Frederick Haldimand recalled them "pending the peace the negotiations in Paris".

The Iroquois also seemed to have a much larger knowledge of the war beyond the scope of New York. A letter from 1782 written by George Washington to John Hanson described intelligence captured from the British. In the letter, British soldiers encounter a group of Native Americans, and a discussion ensues. A soldier by the name of Campbell informs the Native Americans that the war ended and the Americans expressed their sorrow for the war. However, an unknown Seneca sachem informed the British "that the Americans and ench had beat the English, that the latter could no longer carry on the War, and that the Indians knew it well, and must now be sacrificed or submit to the Americans".

After the American Revolution

With the Iroquois League dissolved, the nation settled in new villages along Buffalo Creek, Tonawanda Creek, and Cattaraugus Creek in western New York. The Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Mohawk, as allies of the British, were required to cede all their lands in New York State at the end of the war, as Britain ceded its territory in the Thirteen Colonies to the new United States. The late-war Seneca settlements were assigned to them as their reservations after the Revolutionary War, as part of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784. Although the Oneida and Tuscarora were allies of the rebels, they were also forced to give up most of their territory. On July 8, 1788, the Seneca (along with some Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga tribes) sold rights to land east of theGenesee River

The Genesee River ( ) is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Roch ...

in New York to Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts.

On November 11, 1794, the Seneca (along with the other Haudenosaunee nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States, agreeing to peaceful relations. On September 15, 1797, at the Treaty of Big Tree, the Seneca sold their lands west of the Genesee River, retaining ten reservations for themselves. The sale opened up the rest of Western New York

Western New York (WNY) is the westernmost region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The eastern boundary of the region is not consistently defined by state agencies or those who call themselves "Western New Yorkers". Almost all so ...

for settlement by European Americans. On January 15, 1838, the US and some Seneca leaders signed the Treaty of Buffalo Creek, by which the Seneca were to relocate to a tract of land west of the state of Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, but most refused to go.

The majority of the Seneca in New York formed a modern elected government, the Seneca Nation of Indians, in 1848. The Tonawanda Seneca Nation split off, choosing to keep a traditional form of tribal government. Both tribes are federally recognized in the United States.

Seneca today

While it is not known exactly how many Seneca there are, the three federally recognized tribes are the Seneca Nation of Indians and theTonawanda Band of Seneca Indians

The Tonawanda Seneca Nation (previously known as the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians) () is a federally recognized tribe in the State of New York. They have maintained the traditional form of government led by sachems (hereditary Seneca people, S ...

in New York State and the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma. A fourth group of Seneca people reside in Canada, where many are part of Six Nations in Ontario.

Approximately 10,000 Seneca live near Lake Erie. About 7,800 people are citizens of the Seneca Nation of Indians. These members live or work on five reservations in New York: the Allegany (which contains the city of Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

); the Cattaraugus near Gowanda, New York

Gowanda is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in western New York (state), New York, United States. It lies partly in Erie County, New York, Erie County and partly in Cattaraugus County, New York, Cattaraugus County. The ...

; the Buffalo Creek Territory located in downtown Buffalo; the Niagara Falls Territory located in Niagara Falls, New York; and the Oil Springs Reservation, near Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. Few Seneca reside at the Oil Springs, Buffalo Creek, or Niagara territories due to the small amount of land at each. The last two territories are held and used specifically for the gaming casinos which the tribe has developed.

The Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians

The Tonawanda Seneca Nation (previously known as the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians) () is a federally recognized tribe in the State of New York. They have maintained the traditional form of government led by sachems (hereditary Seneca people, S ...

has about 1,200 citizens who live on their Tonawanda Reservation near Akron, New York.

The third federally recognized tribe is the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma who live near Miami, Oklahoma. They are descendants of Seneca and Cayuga who had migrated from New York into Ohio before the Revolutionary War, under pressure from European encroachment. They were removed to Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s.

Many Seneca and other Iroquois migrated into Canada during and after the Revolutionary War, where the Crown gave them land in compensation for what was lost in their traditional territories. Some 10,000 to 25,000 Seneca are citizens of Six Nations Reserve and reside on the Grand River Territory, the major Iroquois reserve, near Brantford, Ontario

Brantford (Canada 2021 Census, 2021 population: 104,688) is a city in Ontario, Canada, founded on the Grand River (Ontario), Grand River in Southwestern Ontario. It is surrounded by County of Brant, Brant County but is politically separate wi ...

.

Enrolled members of the Seneca Nation also live elsewhere in the United States; some moved to urban locations for work.

The Seneca language was rated "critically endangered" in 2007, with fewer than 50 fluent speakers, primarily the elderly. Efforts are currently underway to preserve and revitalize the language.

Kinzua Dam displacement

The federal government through the Corps of Engineers undertook a major project of a dam for flood control on theAllegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

. The proposed project was planned to affect a major portion of Seneca territory in Pennsylvania and New York. Begun in 1960, construction of the Kinzua Dam on the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

forced the relocation of approximately 600 Seneca from of land which they had occupied under the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. They were relocated to Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

, near the northern shore of the Allegheny Reservoir that resulted from the flooding of land behind the dam. The Seneca had protested the plan for the project, filing suit in court and appealing to President John F. Kennedy to halt construction.

The Seneca lost their court case, and in 1961, citing the immediate need for flood control, Kennedy denied their request. This violation of Seneca rights, as well as those of many other Indian Nations, was memorialized in the 1960s by folksinger Peter La Farge, who wrote, "As Long as the Grass Shall Grow". It was also sung by Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan; born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Described as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture over his nearly 70-year ...

and Johnny Cash

John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American singer-songwriter. Most of his music contains themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially songs from the later stages of his career. ...

.

Leased land disputes

The United States Senate has never ratified the treaty that New York made with the Iroquois nations, and only Congress has the right to make such treaties. In the late 20th century, several tribes filed suit in land claims, seeking to regain their traditional lands by having the treaty declared invalid. The Seneca had other issues with New York and had challenged some long-term leases in court. The dispute centers around a set of 99–year leases that were granted by the Seneca in 1890 for lands that are now in the city of Salamanca and nearby villages. In 1990, Congress passed the Seneca Settlement Act to resolve the long-running land dispute. The Act required the state to pay compensation and to provide some lands. The households that refused to accept Seneca ownership, fifteen in all, were evicted from their homes.Zito, Selena (June 5, 2011)Smokes cheap, tensions high

(Also titled

Portrait of a Failed American City

") ''Pittsburgh Tribune-Review''. Retrieved July 28, 2012. Then, in the early 2000s issues re-arose over Seneca use of settlement lands to establish casino gaming operations, which have generated considerable revenues for many tribes since the late 20th century.

Grand Island claims

On August 25, 1993, the Seneca filed suit in United States District Court to begin an action to reclaim land allegedly taken from it by New York without having gained required approval of the treaty by the US Senate. Only the US government has the constitutional power to make treaties with the Native American nations. The lands consisted of Grand Island and several smaller islands in the Niagara River. in November 1993, the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians moved to join the claim as a plaintiff and was granted standing as a plaintiff. In 1998, the United States intervened in the lawsuits on behalf of the plaintiffs in the claim to allow the claim to proceed against New York. The state had asserted that it was immune from suit under theEleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Eleventh Amendment (Amendment XI) is an amendment to the United States Constitution which was passed by Congress on March 4, 1794, and ratified by the states on February 7, 1795. The Eleventh Amendment restricts the ability of individuals ...

. After extensive negotiations and pre-trial procedures, all parties to the claim moved for judgment as a matter of law.

By decision and order dated June 21, 2002, the trial court held that the Seneca ceded the subject lands to Great Britain in the 1764 treaties of peace after the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(Seven Years' War). Thus, the disputed lands were no longer owned by the Seneca at the time of the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. The court found that the state of New York's "purchase" of the lands from the Seneca in 1815 was intended to avoid conflict with them, but it already owned it by virtue of Great Britain's defeat in the Revolution and the cession of its lands to the United States and by default to the states in which the colonial lands were located.

The Seneca appealed the decision. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the trial court's decision on September 9, 2004. The Seneca sought review of this decision by the US Supreme Court, which on June 5, 2006, announced that it declined to hear the case, which left the lower court rulings in place.

Thruway claims

On April 18, 2007, the Seneca Nation laid claim to a stretch of Interstate 90 that crosses the Cattaraugus Reservation for about three miles, in a section that runs on the northeast side of the lake fromErie, Pennsylvania

Erie is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, fifth-most populous city in Pennsylvania and the most populous in Northwestern Pen ...

to Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

. They said that a 1954 agreement between the Seneca Nation and the New York State Thruway Authority, which granted the state permission to build the highway through their reservation in return for US$75,000, was invalid because it required federal approval. The lawsuit demands that some of the toll money collected by the Thruway Authority for the use of this three-mile stretch of the highway be remitted to the Nation. In 2011, Seneca President Robert Odawi Porter said that the Nation should be paid $1 every time a vehicle drives that part of the highway, amounting to tens of millions of dollars. The Nation also disputed the state's attempts to collect cigarette taxes and casino revenue from tribal businesses operating within Seneca sovereign territory. , the lawsuit over the thruway was ongoing.

The Seneca had previously brought suit against the state on the issue of highway easements. The court in 1999 had ruled that the State could not be sued by the tribe. US District Court, ''Seneca Tribe, et. al, v. State of New York, Gov. Pataki, et al.'', Feb 1999 In Magistrate Heckman's "Report and Recommendation", it was noted that the State of New York asserted its immunity from suit against both counts of the complaint. One count was the Seneca Tribe's challenge regarding the state's acquisition of Grand Island and other smaller islands in the Niagara River, and the second count challenged the state's thruway easement.

Economy

Diversified businesses

The Seneca have a diversified economy that relies on construction, communications, recreation, tourism, and retail sales. They have recently started operating two tribal-owned gaming casinos and recreation complexes. Several large construction companies are located on the Cattaraugus and Allegany Territories. Many smaller construction companies are owned and operated by Seneca people. A considerable number of Seneca men work in some facet of the construction industry. Recreation is one component of Seneca enterprises. The Highbanks Campground (reopened May 2015 after being closed in 2013) plays host to visitors in summer, as people take in the scenic vistas and enjoy the Allegheny Reservoir. Several thousand fishing licenses are sold each year to non-Seneca fishermen. Many of these customers are tourists to the region. Several major highways adjacent to or on the Seneca Nation Territories provide ready accessibility to local, regional and national traffic. Many tourists visit the region during the autumn for the fall foliage. A substantial portion of the Seneca economy revolves around retail sales. From gas stations, smokeshops, and sports apparel, candles and artwork to traditional crafts, the wide range of products for sale on Seneca Nation Territories reflect the diverse interests of Seneca Nation citizens.Seneca Medical Marijuana Initiative

According to Bill Wagner, an author writing for High Times, "Members of the Seneca Nation of Indians in western New York state voted up a referendum Nov. 3 (2016) giving tribal leaders approval to move towards setting up a medical marijuana business on their territories. The measure passed by a vote of 448-364, giving the Seneca Nation Council the power to draft laws and regulations allowing the manufacture, use and distribution of cannabis for medical purposes. "A decision on our Nation's path of action on medical cannabis is far from made", cautioned Seneca President Maurice A. John Sr. in comments to the ''Buffalo News''. "But now, having heard from the Seneca people, our discussions and due diligence can begin in earnest." Entering the marijuana industry is thought to help stimulate the economy of the Seneca Tribe and create local business, dispensaries and other types of jobs involving medical marijuana.Tax-free gasoline and cigarette sales

The price advantage of the Senecas' ability to sell tax-free gasoline and cigarettes has created a boom in their economy. They have established many service stations along the state highways that run through the reservations, as well as many internet cigarette stores. Competing business interests and the state government object to their sales over the Internet. The state of New York believes that the tribe's sales of cigarettes by Internet are illegal. It also believes that the state has the authority to tax non-Indians who patronize Seneca businesses, a principle which the Seneca reject. Seneca President Barry Snyder has defended the price advantage as an issue of sovereignty. Secondly, he has cited the Treaty of Canandaigua and Treaty of Buffalo Creek as the basis of Seneca exemption from collecting taxes on cigarettes to pay the state. The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court, Third Department had rejected this conclusion in 1994. The court held that the provisions of the treaty regarding taxation was only with regard to property taxes. The New York Court of Appeals on December 1, 1994, affirmed the lower court's decision. The Seneca have refused to extend these benefits and price advantages to non-Indians, in their own words "has little sympathy for outsiders" who desire to do so, They have tried to prosecute non-Indians who have attempted to claim the price advantages of the Seneca while operating a business on the reservation. Little Valley businessman Lloyd Long operated two Uni-Marts on the reservation which were owned by a Seneca woman. He was arrested after investigation by federal authorities at the behest of the Seneca Nation accusing the native woman of being a front for Long. In 2011 he was ordered by the court to pay more than one million dollars in restitution and serve five years on probation. In 1997, New York State had attempted to enforce taxation on reservation sales of gasoline and cigarettes to non-Indians. Numerous Seneca had protested by setting fire to tires and cutting off traffic to Interstate 90 and New York State Route 17 (the future Interstate 86). Then Attorney General Eliot Spitzer attempted to cut off the Seneca Tribe's internet cigarette sales by way of financial deplatforming. His office negotiated directly with credit card companies, tobacco companies, and delivery services to try to gain agreement to reject handling Seneca cigarette purchases by consumers. Another attempt at collecting taxes on gasoline and cigarettes sold to non-Indians was set to begin March 1, 2006; but it was tabled by the State Department of Taxation and Finance. Shortly after March 1, 2006, other parties began proceedings to compel the State of New York to enforce its tax laws on sales to non-Indians on Indian land. Seneca County filed a suit which was dismissed. The New York State Association of Convenience Stores filed a similar suit, which was also dismissed. Based on the dismissal of these proceedings, Daniel Warren, a member and officer of Upstate Citizens for Equality, moved to vacate the judgment dismissing his 2002 state court action. The latter was dismissed because the court ruled that he had lack of standing. In response to Governor Eliot Spitzer's inclusion of $200 million of revenue in his budget from the cigarette tax, the Seneca announced plans to collect a toll from all who travel the length of I-90 that goes through their reservation. In 2007 the Senecas rescinded the agreement that had permitted construction of the thruway and its attendant easement through their reservation. Some commentators have contended that this agreement was not necessary or moot because the United States was already granted free right-of-passage across the Seneca land in the Treaty of Canandaigua. In 2008 Governor David Paterson included $62 million of revenue in his budget from the proposed collection of these taxes. He signed a new law requiring that manufacturers and wholesalers swear under penalty of perjury that they are not selling untaxed cigarettes in New York. A law to bar any tax-exempt organization in New York from receiving tax-free cigarettes went into effect June 21, 2011. The Seneca nation has repeatedly appealed the decision, continuing to do so as of June 2011, but has not gained an overturn of this law. The state has enforced the law only on cigarette brands produced by non-Indian companies (including all major national brands). It has not attempted to collect taxes on brands that are entirely tribally produced and sold (these are generally lower-end and lower-cost brands that have always made up the majority of Seneca cigarette sales.)Casinos