Seneca the Younger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

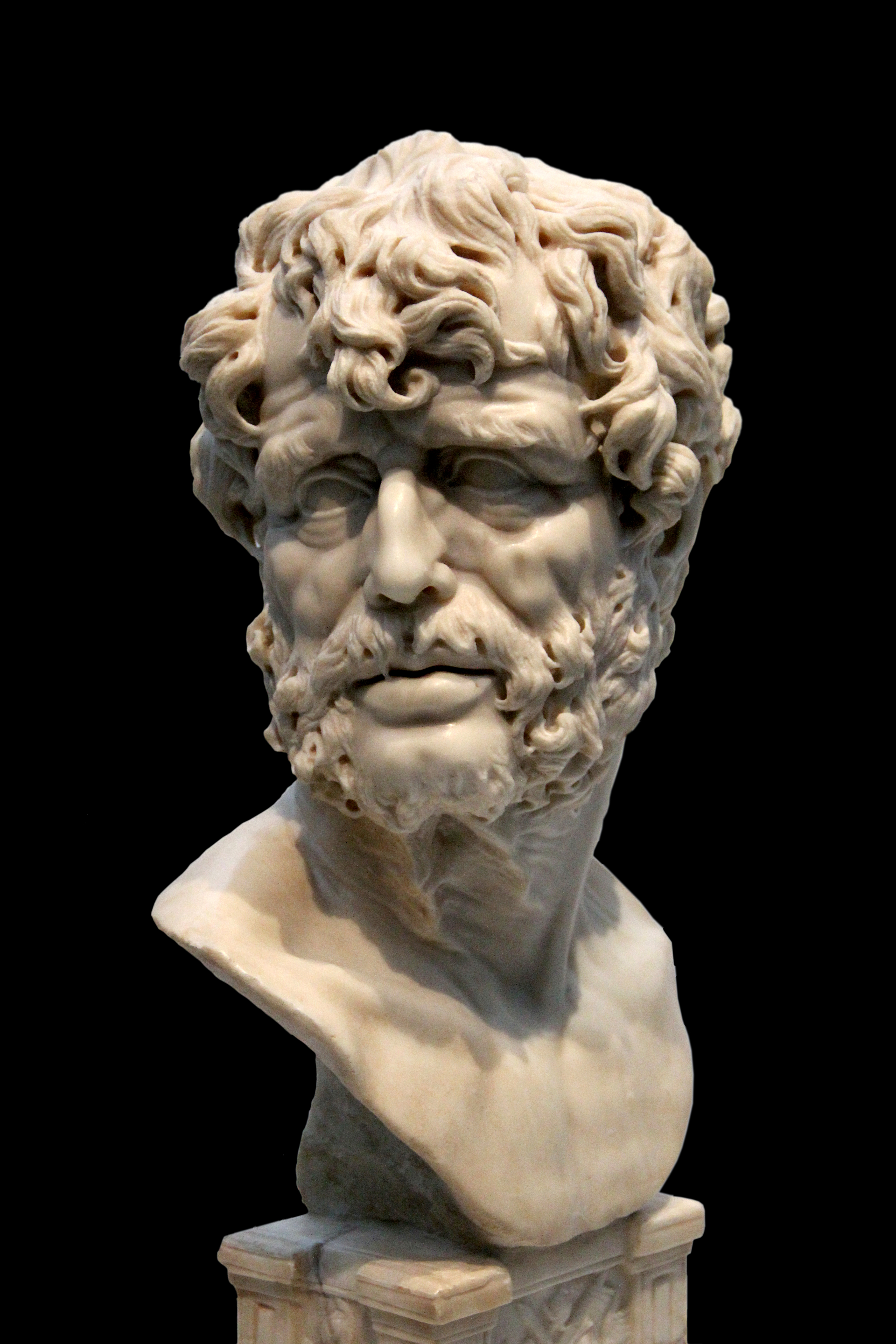

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of

Seneca tells us that he was taken to

Seneca tells us that he was taken to

From AD 54 to 62, Seneca acted as Nero's advisor, together with the

From AD 54 to 62, Seneca acted as Nero's advisor, together with the

In AD 65, Seneca was caught up in the aftermath of the

In AD 65, Seneca was caught up in the aftermath of the

As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period", Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of

As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period", Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of

Ten plays are attributed to Seneca, of which most likely eight were written by him. The plays stand in stark contrast to his philosophical works. With their intense emotions, and grim overall tone, the plays seem to represent the antithesis of Seneca's Stoic beliefs. Up to the 16th century it was normal to distinguish between Seneca the moral philosopher and Seneca the dramatist as two separate people. Scholars have tried to spot certain Stoic themes: it is the uncontrolled passions that generate madness, ruination, and self-destruction. This has a cosmic as well as an ethical aspect, and fate is a powerful, albeit rather oppressive, force.

Many scholars have thought, following the ideas of the 19th-century German scholar

Ten plays are attributed to Seneca, of which most likely eight were written by him. The plays stand in stark contrast to his philosophical works. With their intense emotions, and grim overall tone, the plays seem to represent the antithesis of Seneca's Stoic beliefs. Up to the 16th century it was normal to distinguish between Seneca the moral philosopher and Seneca the dramatist as two separate people. Scholars have tried to spot certain Stoic themes: it is the uncontrolled passions that generate madness, ruination, and self-destruction. This has a cosmic as well as an ethical aspect, and fate is a powerful, albeit rather oppressive, force.

Many scholars have thought, following the ideas of the 19th-century German scholar

* (54) ''

* (54) ''

disputed

Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and

Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and

Seneca remains one of the few popular Roman philosophers from the period. He appears not only in

Seneca remains one of the few popular Roman philosophers from the period. He appears not only in  Among the historians who have sought to reappraise Seneca is the scholar Anna Lydia Motto, who in 1966 argued that the negative image has been based almost entirely on Suillius's account, while many others who might have lauded him have been lost.

Among the historians who have sought to reappraise Seneca is the scholar Anna Lydia Motto, who in 1966 argued that the negative image has been based almost entirely on Suillius's account, while many others who might have lauded him have been lost.

Seneca is a character in

Seneca is a character in

"Connections between Seneca and Platonism in Epistulae ad Lucilium 58"

Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: PHI2015-1445. * Fitch, John G. (ed), ''Seneca.'' Oxford University Press, 2008. . A collection of essays by leading scholars. * * Griffin, Miriam T., ''Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics.'' Oxford University Press, 1976. . Still the standard biography. * Inwood, Brad, ''Reading Seneca. Stoic Philosophy at Rome'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. * Lucas, F. L.

''Seneca and Elizabethan Tragedy''

(Cambridge University Press, 1922; paperback 2009, ); on Seneca the man, his plays, and the influence of his tragedies on later drama.

Mitchell, David. ''Legacy: The Apocryphal Correspondence between Seneca and Paul''

Xlibris Corporation 2010 * Motto, Anna Lydia

”Seneca on Death and Immortality“

''The Classical Journal'', Vol. 50, No. 4 (Jan. 1955), pp. 187–189 * Motto, Anna Lydia

"Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic"

''The Classical Journal'', Vol. 61, No. 6 (March 1966), pp. 254–258

Sevenster, J.N.

''Paul and Seneca''

Novum Testamentum, Supplements

Vol. 4, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1961; a comparison of Seneca and the apostle Paul, who were contemporaries.

Shelton, Jo-Ann''Seneca's Hercules Furens: Theme, Structure and Style''

Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978. . A revision of the author's doctoral thesis at the

Works by Seneca the Younger at Perseus Digital Library

* * * Original texts of Seneca's works a

* * * *

Collection of works of Seneca the Younger at Wikisource

* ttp://www.curculio.org/Seneca/em-list.html List of commentaries of Seneca's Letters

Incunabula (1478) of Seneca's works in the McCune Collection

, read by Katharina Volk, Columbia University. Society for the Oral reading of Greek and Latin Literature (SORGLL)

Digitized works by Lucius Annaeus Seneca

at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España

Guide to Seneca, Lucius Annaeus, Spurious works. Manuscript, ca. 1450

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

Digitized Edition of Seneca's Opera Omnia from 1503

(Venice) a

E-rara.ch

{{Authority control 0s BC births Year of birth uncertain 65 deaths 1st-century executions 1st-century philosophers 1st-century Romans 1st-century writers Ancient Roman tragic dramatists Ancient Romans who committed suicide Annaei Ethicists Executed philosophers Executed writers Forced suicides Latin letter writers Literary theorists Male dramatists and playwrights Male essayists Male poets Members of the Pisonian conspiracy Moral philosophers People executed by the Roman Empire People from Córdoba, Spain Philosophers of art Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of mind Philosophers of social science Philosophers of Roman Italy Political philosophers Roman encyclopedists Roman-era historians Roman-era philosophers Roman-era satirists Roman-era Stoic philosophers Romans from Hispania Silver Age Latin writers Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome

Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–50 ...

, a statesman, dramatist

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

.

Seneca was born in Córdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, 2nd largest city in the country and capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cordoba may ...

in Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: His ...

, and raised in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he was trained in rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

and philosophy. His father was Seneca the Elder

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder (; c. 54 BC – c. 39 AD), also known as Seneca the Rhetorician, was a Roman writer, born of a wealthy equestrian family of Corduba, Hispania. He wrote a collection of reminiscences about the Roman schools of rhe ...

, his elder brother was Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus

Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus or Gallio ( el, Γαλλιων, ''Galliōn''; c. 5 BC – c. AD 65) was a Roman senator and brother of the famous writer Seneca. He is best known for dismissing an accusation brought against Paul the Apostle in Co ...

, and his nephew was the poet Lucan. In AD 41, Seneca was exiled to the island of Corsica under emperor Claudius, but was allowed to return in 49 to become a tutor to Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

. When Nero became emperor in 54, Seneca became his advisor and, together with the praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus, provided competent government for the first five years of Nero's reign. Seneca's influence over Nero declined with time, and in 65 Seneca was forced to take his own life for alleged complicity in the Pisonian conspiracy

The conspiracy of Gaius Calpurnius Piso in AD 65 was a in the reign of the Roman emperor Nero (reign 54–68). The plot reflected the growing discontent among the ruling class of the Roman state with Nero's increasingly despotic leadership, ...

to assassinate Nero, in which he was probably innocent. His stoic and calm suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

has become the subject of numerous paintings.

As a writer, Seneca is known for his philosophical works, and for his plays, which are all tragedies. His prose works include 12 essays and 124 letters dealing with moral issues. These writings constitute one of the most important bodies of primary material for ancient Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that ...

. As a tragedian, he is best known for plays such as his ''Medea

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the ...

'', ''Thyestes

In Greek mythology, Thyestes (pronounced , gr, Θυέστης, ) was a king of Olympia. Thyestes and his brother, Atreus, were exiled by their father for having murdered their half-brother, Chrysippus, in their desire for the throne of Olympi ...

'', and ''Phaedra

Phaedra may refer to:

Mythology

* Phaedra (mythology), Cretan princess, daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, wife of Theseus

Arts and entertainment

* ''Phaedra'' (Alexandre Cabanel), an 1880 painting

Film

* ''Phaedra'' (film), a 1962 film by ...

''. Seneca's influence on later generations is immense—during the Renaissance he was "a sage admired and venerated as an oracle of moral, even of Christian edification; a master of literary style and a model ordramatic art."

Life

Early life, family and adulthood

Seneca was born inCórdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, 2nd largest city in the country and capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cordoba may ...

in the Roman province of Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula). Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of the basic d ...

in Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: His ...

. His father was Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder, a Spanish-born Roman knight

The ''equites'' (; literally "horse-" or "cavalrymen", though sometimes referred to as "knights" in English) constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian o ...

who had gained fame as a writer and teacher of rhetoric in Rome. Seneca's mother, Helvia, was from a prominent Baetician family. Seneca was the second of three brothers; the others were Lucius Annaeus Novatus (later known as Junius Gallio), and Annaeus Mela, the father of the poet Lucan. Miriam Griffin says in her biography of Seneca that "the evidence for Seneca's life before his exile in 41 is so slight, and the potential interest of these years, for social history, as well as for biography, is so great that few writers on Seneca have resisted the temptation to eke out knowledge with imagination."Miriam T. Griffin. ''Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics'', Oxford 1976. 34. Griffin also infers from the ancient sources that Seneca was born in either 8, 4, or 1 BC. She thinks he was born between 4 and 1 BC and was resident in Rome by 5 AD.

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in the "arms" of his aunt (his mother's stepsister) at a young age, probably when he was about five years old. His father resided for much of his life in the city. Seneca was taught the usual subjects of literature, grammar, and rhetoric, as part of the standard education of high-born Romans. While still young he received philosophical training from Attalus Attalus or Attalos may refer to:

People

*Several members of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon

** Attalus I, ruled 241 BC–197 BC

** Attalus II Philadelphus, ruled 160 BC–138 BC

** Attalus III, ruled 138 BC–133 BC

*Attalus, father of ...

the Stoic, and from Sotion and Papirius Fabianus, both of whom belonged to the short-lived School of the Sextii, which combined Stoicism with Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

. Sotion persuaded Seneca when he was a young man (in his early twenties) to become a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat ( red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetaria ...

, which he practiced for around a year before his father urged him to desist because the practice was associated with "some foreign rites". Seneca often had breathing difficulties throughout his life, probably asthma, and at some point in his mid-twenties (c. 20 AD) he appears to have been struck down with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

. He was sent to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

to live with his aunt (the same aunt who had brought him to Rome), whose husband Gaius Galerius

Gaius Galerius was a Roman '' eques'' who was active during the reign of Tiberius. He is best known as the ''praefectus'' or governor of Egypt (16-32).

Galerius came of a prominent family of Ariminum. He has been identified as the husband of the s ...

had become Prefect of Egypt. She nursed him through a period of ill health that lasted up to ten years. In 31 AD he returned to Rome with his aunt, his uncle dying en route in a shipwreck. His aunt's influence helped Seneca be elected quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

(probably after 37 AD), which also earned him the right to sit in the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

.

Politics and exile

Seneca's early career as a senator seems to have been successful and he was praised for his oratory.Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

relates a story that Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanic ...

was so offended by Seneca's oratorical success in the Senate that he ordered him to commit suicide. Seneca survived only because he was seriously ill and Caligula was told that he would soon die anyway. In his writings Seneca has nothing good to say about Caligula and frequently depicts him as a monster. Seneca explains his own survival as due to his patience and his devotion to his friends: "I wanted to avoid the impression that all I could do for loyalty was die."

In 41 AD, Claudius became emperor, and Seneca was accused by the new empress Messalina

Valeria Messalina (; ) was the third wife of Roman emperor Claudius. She was a paternal cousin of Emperor Nero, a second cousin of Emperor Caligula, and a great-grandniece of Emperor Augustus. A powerful and influential woman with a reputation ...

of adultery with Julia Livilla, sister to Caligula and Agrippina

Agrippina is an ancient Roman cognomen and a feminine given name. People with either the cognomen or the given name include:

Cognomen

Relatives of the Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa:

* Vipsania Agrippina (36 BC–20 AD), first wife of th ...

. The affair has been doubted by some historians, since Messalina had clear political motives for getting rid of Julia Livilla and her supporters. The Senate pronounced a death sentence on Seneca, which Claudius commuted to exile, and Seneca spent the next eight years on the island of Corsica. Two of Seneca's earliest surviving works date from the period of his exile—both consolations. In his ''Consolation to Helvia'', his mother, Seneca comforts her as a bereaved mother for losing her son to exile. Seneca incidentally mentions the death of his only son, a few weeks before his exile. Later in life Seneca was married to a woman younger than himself, Pompeia Paulina. It has been thought that the infant son may have been from an earlier marriage, but the evidence is "tenuous". Seneca's other work of this period, his ''Consolation to Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

'', one of Claudius' freedmen, focused on consoling Polybius on the death of his brother. It is noted for its flattery of Claudius, and Seneca expresses his hope that the emperor will recall him from exile. In 49 AD Agrippina married her uncle Claudius, and through her influence Seneca was recalled to Rome. Agrippina gained the praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vario ...

ship for Seneca and appointed him tutor to her son, the future emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

.

Imperial advisor

praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

Sextus Afranius Burrus. One by-product of his new position was that Seneca was appointed suffect consul

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which politic ...

in 56. Seneca's influence was said to have been especially strong in the first year. Seneca composed Nero's accession speeches in which he promised to restore proper legal procedure and authority to the Senate. He also composed the eulogy for Claudius that Nero delivered at the funeral. Seneca's satirical skit '' Apocolocyntosis'', which lampoons the deification of Claudius and praises Nero, dates from the earliest period of Nero's reign. In 55 AD, Seneca wrote '' On Clemency'' following Nero's murder of Britannicus, perhaps to assure the citizenry that the murder was the end, not the beginning of bloodshed. ''On Clemency'' is a work which, although it flatters Nero, was intended to show the correct (Stoic) path of virtue for a ruler. Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

and Dio suggest that Nero's early rule, during which he listened to Seneca and Burrus, was quite competent. However, the ancient sources suggest that, over time, Seneca and Burrus lost their influence over the emperor. In 59 they had reluctantly agreed to Agrippina's murder, and afterward Tacitus reports that Seneca had to write a letter justifying the murder to the Senate.

In 58 AD the senator Publius Suillius Rufus

Publius may refer to:

Roman name

* Publius (praenomen)

* Ancient Romans with the name:

** Publius Valerius Publicola (died 503 BC), Roman consul, co-founder of the Republic

** Publius Clodius Pulcher (c. 93 BC – 52 BC), Republican politicia ...

made a series of public attacks on Seneca. These attacks, reported by Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

and Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, included charges that, in a mere four years of service to Nero, Seneca had acquired a vast personal fortune of three hundred million sestertii by charging high interest on loans throughout Italy and the provinces. Suillius' attacks included claims of sexual corruption, with a suggestion that Seneca had slept with Agrippina. Tacitus, though, reports that Suillius was highly prejudiced: he had been a favorite of Claudius, and had been an embezzler and informant. In response, Seneca brought a series of prosecutions for corruption against Suillius: half of his estate was confiscated and he was sent into exile. However, the attacks reflect a criticism of Seneca that was made at the time and continued through later ages. Seneca was undoubtedly extremely rich: he had properties at Baiae

Baiae ( it, Baia; nap, Baia) was an ancient Roman town situated on the northwest shore of the Gulf of Naples and now in the ''comune'' of Bacoli. It was a fashionable resort for centuries in antiquity, particularly towards the end of the Roman ...

and Nomentum, an Alban villa, and Egyptian estates. Cassius Dio even reports that the Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as ()), was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. Sh ...

uprising in Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Gr ...

was caused by Seneca forcing large loans on the indigenous British aristocracy in the aftermath of Claudius's conquest of Britain, and then calling them in suddenly and aggressively. Seneca was sensitive to such accusations: his '' De Vita Beata'' ("On the Happy Life") dates from around this time and includes a defense of wealth along Stoic lines, arguing that properly gaining and spending wealth is appropriate behavior for a philosopher.

Retirement

After Burrus's death in 62, Seneca's influence declined rapidly; as Tacitus puts it (Ann. 14.52.1), ''mors Burri infregit Senecae potentiam'' ("the death of Burrus broke Seneca's power"). Tacitus reports that Seneca tried to retire twice, in 62 and 64 AD, but Nero refused him on both occasions. Nevertheless, Seneca was increasingly absent from the court. He adopted a quiet lifestyle on his country estates, concentrating on his studies and seldom visiting Rome. It was during these final few years that he composed two of his greatest works: '' Naturales quaestiones''—an encyclopedia of the natural world; and his '' Letters to Lucilius''—which document his philosophical thoughts.Death

In AD 65, Seneca was caught up in the aftermath of the

In AD 65, Seneca was caught up in the aftermath of the Pisonian conspiracy

The conspiracy of Gaius Calpurnius Piso in AD 65 was a in the reign of the Roman emperor Nero (reign 54–68). The plot reflected the growing discontent among the ruling class of the Roman state with Nero's increasingly despotic leadership, ...

, a plot to kill Nero. Although it is unlikely that Seneca was part of the conspiracy, Nero ordered him to kill himself. Seneca followed tradition by severing several vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenate ...

s in order to bleed to death, and his wife Pompeia Paulina attempted to share his fate. Cassius Dio, who wished to emphasize the relentlessness of Nero, focused on how Seneca had attended to his last-minute letters, and how his death was hastened by soldiers. A generation after the Julio-Claudian emperors, Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

wrote an account of the suicide, which, in view of his Republican sympathies, is perhaps somewhat romanticized. citing Tacitus '' Annals'', xv. 60–64 According to this account, Nero ordered Seneca's wife saved. Her wounds were bound up and she made no further attempt to kill herself. As for Seneca himself, his age and diet were blamed for slow loss of blood and extended pain rather than a quick death. He also took poison, which was, however, not fatal. After dictating his last words to a scribe, and with a circle of friends attending him in his home, he immersed himself in a warm bath, which he expected would speed blood flow and ease his pain. Tacitus wrote, "He was then carried into a bath, with the steam of which he was suffocated, and he was burnt without any of the usual funeral rites. So he had directed in a codicil of his will, even when in the height of his wealth and power he was thinking of life's close." This may give the impression of a favorable portrait of Seneca, but Tacitus's treatment of him is at best ambivalent. Alongside Seneca's apparent fortitude in the face of death, for example, one can also view his actions as rather histrionic and performative; and when Tacitus tells us that he left his family an ''imago suae vitae'' (''Annales'' 15.62), "an image of his life", he is possibly being ambiguous: in Roman culture, the ''imago'' was a kind of mask that commemorated the great ancestors of noble families, but at the same time, it may also suggest duplicity, superficiality, and pretense.

Philosophy

As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period", Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of

As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period", Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that ...

. His writing is highly accessible and was the subject of attention from the Renaissance onwards by writers such as Michel de Montaigne. He has been described as “a towering and controversial figure of antiquity” and “the world’s most interesting Stoic”.

Seneca wrote a number of books on Stoicism, mostly on ethics, with one work ('' Naturales Quaestiones'') on the physical world. Seneca built on the writings of many of the earlier Stoics: he often mentions Zeno, Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; grc-gre, Κλεάνθης; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a box ...

, and Chrysippus; and frequently cites Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, wikt:Ποσειδώνιος, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apamea (Syria), Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greeks, Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geog ...

, with whom Seneca shared an interest in natural phenomena. He frequently quotes Epicurus, especially in his '' Letters''. His interest in Epicurus is mainly limited to using him as a source of ethical maxims. Likewise Seneca shows some interest in Platonist

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at ...

metaphysics, but never with any clear commitment. His moral essays are based on Stoic doctrines. Stoicism was a popular philosophy in this period, and many upper-class Romans found in it a guiding ethical framework for political involvement. It was once popular to regard Seneca as being very eclectic in his Stoicism, but modern scholarship views him as a fairly orthodox Stoic, albeit a free-minded one.

His works discuss both ethical theory and practical advice, and Seneca stresses that both parts are distinct but interdependent. His '' Letters to Lucilius'' showcase Seneca's search for ethical perfection and “represent a sort of philosophical testament for posterity”. Seneca regards philosophy as a balm for the wounds of life. The destructive passions, especially anger and grief, must be uprooted, or moderated according to reason. He discusses the relative merits of the contemplative life and the active life, and he considers it important to confront one's own mortality and be able to face death. One must be willing to practice poverty and use wealth properly, and he writes about favours, clemency, the importance of friendship, and the need to benefit others. The universe is governed for the best by a rational providence, and this must be reconciled with acceptance of adversity.

Drama

Ten plays are attributed to Seneca, of which most likely eight were written by him. The plays stand in stark contrast to his philosophical works. With their intense emotions, and grim overall tone, the plays seem to represent the antithesis of Seneca's Stoic beliefs. Up to the 16th century it was normal to distinguish between Seneca the moral philosopher and Seneca the dramatist as two separate people. Scholars have tried to spot certain Stoic themes: it is the uncontrolled passions that generate madness, ruination, and self-destruction. This has a cosmic as well as an ethical aspect, and fate is a powerful, albeit rather oppressive, force.

Many scholars have thought, following the ideas of the 19th-century German scholar

Ten plays are attributed to Seneca, of which most likely eight were written by him. The plays stand in stark contrast to his philosophical works. With their intense emotions, and grim overall tone, the plays seem to represent the antithesis of Seneca's Stoic beliefs. Up to the 16th century it was normal to distinguish between Seneca the moral philosopher and Seneca the dramatist as two separate people. Scholars have tried to spot certain Stoic themes: it is the uncontrolled passions that generate madness, ruination, and self-destruction. This has a cosmic as well as an ethical aspect, and fate is a powerful, albeit rather oppressive, force.

Many scholars have thought, following the ideas of the 19th-century German scholar Friedrich Leo

Friedrich Leo (July 10, 1851 – January 15, 1914) was a German classical philologist born in Regenwalde, in the then- province of Pomerania (present-day Resko, Poland).

Academic career

From 1868 he was a student at the University of Göttinge ...

, that Seneca's tragedies were written for recitation only. Other scholars think that they were written for performance and that it is possible that actual performance took place in Seneca's lifetime. Ultimately, this issue cannot be resolved on the basis of our existing knowledge. The tragedies of Seneca have been successfully staged in modern times.

The dating of the tragedies is highly problematic in the absence of any ancient references. A parody of a lament from '' Hercules Furens'' appears in the '' Apocolocyntosis'', which implies a date before 54 AD for that play. A relative chronology has been proposed on metrical grounds. The plays are not all based on the Greek pattern; they have a five-act form and differ in many respects from extant Attic drama, and while the influence of Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

on some of these works is considerable, so is the influence of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

and Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the ...

.

Seneca's plays were widely read in medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

an universities

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which ...

and strongly influenced tragic drama in that time, such as Elizabethan England (William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

and other playwrights), France ( Corneille and Racine), and the Netherlands ( Joost van den Vondel). English translations of Seneca's tragedies appeared in print in the mid-16th century, with all ten published collectively in 1581. He is regarded as the source and inspiration for what is known as "Revenge Tragedy", starting with Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of '' The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time ...

's '' The Spanish Tragedy'' and continuing well into the Jacobean era. ''Thyestes'' is considered Seneca's masterpiece, and has been described by scholar Dana Gioia as "one of the most influential plays ever written". ''Medea'' is also highly regarded, and was praised along with ''Phaedra'' by T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

.

Works

Works attributed to Seneca include 12 philosophical essays, 124 letters dealing with moral issues, nine tragedies, and asatire

Satire is a genre of the visual arts, visual, literature, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently Nonfiction, non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ...

, the attribution of which is disputed. His authorship of ''Hercules on Oeta'' has also been questioned.

Seneca's tragedies

'' Fabulae crepidatae'' (tragedies with Greek subjects): * ''Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted th ...

'' or ''Hercules furens'' (''The Madness of Hercules'')

* '' Troades'' (''The Trojan Women'')

* '' Phoenissae'' (''The Phoenician Women'')

* ''Medea

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the ...

''

* ''Phaedra

Phaedra may refer to:

Mythology

* Phaedra (mythology), Cretan princess, daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, wife of Theseus

Arts and entertainment

* ''Phaedra'' (Alexandre Cabanel), an 1880 painting

Film

* ''Phaedra'' (film), a 1962 film by ...

''

* '' Oedipus''

* ''Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husb ...

''

* ''Thyestes

In Greek mythology, Thyestes (pronounced , gr, Θυέστης, ) was a king of Olympia. Thyestes and his brother, Atreus, were exiled by their father for having murdered their half-brother, Chrysippus, in their desire for the throne of Olympi ...

''

* '' Hercules Oetaeus'' (''Hercules on Oeta''): generally considered not written by Seneca. First rejected by Daniël Heinsius

Daniel Heinsius (or Heins) (9 June 158025 February 1655) was one of the most famous scholars of the Dutch Renaissance.

His youth and student years

Heinsius was born in Ghent. The troubles of the Spanish war drove his parents to settle first at ...

.

'' Fabula praetexta'' (tragedy in Roman setting):

* '' Octavia'': almost certainly not written by Seneca (at least in its final form) since it contains accurate prophecies of both his and Nero's deaths. This play closely resembles Seneca's plays in style, but was probably written some time after Seneca's death (perhaps under Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

) by someone influenced by Seneca and aware of the events of his lifetime. Though attributed textually to Seneca, the attribution was early questioned by Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credite ...

, and rejected by Justus Lipsius.

Essays and letters

Essays

''Traditionally given in the following order:'' # (64) ''De Providentia

''De Providentia'' (''On Providence'') is a short essay in the form of a dialogue in six brief sections, written by the Latin philosopher Seneca (died AD 65) in the last years of his life. He chose the dialogue form (as in the well-known Plat ...

'' (''On providence'') – addressed to Lucilius

# (55) '' De Constantia Sapientis'' (''On the Firmness of the Wise Person'') – addressed to Serenus

# (41) '' De Ira'' (''On anger'') – A study on the consequences and the control of anger – addressed to his brother Novatus

# (book 2 of the ''De Ira'')

# (book 3 of the ''De Ira'')

# (40) '' Ad Marciam, De consolatione'' (''To Marcia, On Consolation'') – Consoles her on the death of her son

# (58) '' De Vita Beata'' (''On the Happy Life'') – addressed to Gallio

# (62) '' De Otio'' (''On Leisure'') – addressed to Serenus

# (63) '' De Tranquillitate Animi'' (''On the tranquillity of mind'') – addressed to Serenus

# (49) '' De Brevitate Vitæ'' (''On the shortness of life'') – Essay expounding that any length of life is sufficient if lived wisely – addressed to Paulinus

# (44) '' De Consolatione ad Polybium'' (''To Polybius, On consolation'') – Consoling him on the death of his brother.

# (42) '' Ad Helviam matrem, De consolatione'' (''To mother Helvia, On consolation'') – Letter to his mother consoling her on his absence during exile.

Other essays

* (56) ''De Clementia

''De Clementia'' (frequently translated as ''On Mercy'' in English) is a two volume (incomplete) hortatory essay written in AD 55–56 by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, to the emperor Nero in the first five years of his reign.

D ...

'' (''On Clemency'') – written to Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

on the need for clemency as a virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is morality, moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is Value (ethics), valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that sh ...

in an emperor.

* (63) '' De Beneficiis'' (''On Benefits'') even books

Even may refer to:

General

* Even (given name), a Norwegian male personal name

* Even (surname)

* Even (people), an ethnic group from Siberia and Russian Far East

**Even language, a language spoken by the Evens

* Odd and Even, a solitaire game wh ...

* (–) ''De Superstitione'' (''On Superstition'') – lost, but quoted from in Saint Augustine's City of God 6.10–6.11.

Letters

* (64) '' Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium'' – collection of 124 letters, sometimes divided into 20 books, dealing with moral issues written to Lucilius Junior. This work has possibly come down to us incomplete; the miscellanist Aulus Gellius refers, in his ''Noctes Atticae'' (12.2), to a 'book 22'.Other

* (54) ''

* (54) ''Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii

The ''Apocolocyntosis (divi) Claudii'', literally ''The Pumpkinification of ''(''the Divine'')'' Claudius'', is a satire on the Roman emperor Claudius, which, according to Cassius Dio, was written by Seneca the Younger. A partly extant Menippean ...

'' (''The Gourdification of the Divine Claudius''), a satirical work.

* (63) '' Naturales quaestiones'' even books

Even may refer to:

General

* Even (given name), a Norwegian male personal name

* Even (surname)

* Even (people), an ethnic group from Siberia and Russian Far East

**Even language, a language spoken by the Evens

* Odd and Even, a solitaire game wh ...

an insight into ancient theories of cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

, meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, and similar subjects.

Spurious

* (58–62/370?) '' Cujus etiam ad Paulum apostolum leguntur epistolae:'' These letters, allegedly between Seneca and St Paul, were revered by early authorities, but modern scholarship rejects their authenticity."Pseudo-Seneca"

Various antique and medieval texts purport to be by Seneca, ''e.g.'', ''De remediis fortuitorum''. Their unknown authors are collectively called "Pseudo-Seneca." At least some of these seem to preserve and adapt genuine Senecan content, for example, SaintMartin of Braga

Martin of Braga (in Latin ''Martinus Bracarensis'', in Portuguese, known as ''Martinho de Dume'' 520–580 AD) was an archbishop of Bracara Augusta in Gallaecia (now Braga in Portugal), a missionary, a monastic founder, and an ecclesiasti ...

's (d. c. 580) ''Formula vitae honestae'', or ''De differentiis quatuor virtutum vitae honestae'' ("Rules for an Honest Life", or "On the Four Cardinal Virtues"). Early manuscripts preserve Martin's preface, where he makes it clear that this was his adaptation, but in later copies this was omitted, and the work was later thought fully Seneca's work. Seneca is also often quoted as the author of the aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by t ...

: "Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful"; this is based on a translation by Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

, but idisputed

Editions

*Legacy

As a proto-Christian saint

Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and

Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintili ...

, writing thirty years after Seneca's death, remarked on the popularity of his works amongst the youth. While he found much to admire, Quintillian criticized Seneca for what he regarded as a degenerate literary style—a criticism echoed by Aulus Gellius

Aulus Gellius (c. 125after 180 AD) was a Roman author and grammarian, who was probably born and certainly brought up in Rome. He was educated in Athens, after which he returned to Rome. He is famous for his ''Attic Nights'', a commonplace book ...

in the middle of the 2nd century. citing Quintilian, ''Institutio Oratoria'', x.1.126f; Aulus Gellius, ''Noctes Atticae'', xii. 2.

The early Christian Church was very favourably disposed towards Seneca and his writings, and the church leader Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of ...

possessively referred to him as "our Seneca". By the 4th century an apocryphal correspondence with Paul the Apostle had been created linking Seneca into the Christian tradition. The letters are mentioned by Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is co ...

who also included Seneca among a list of Christian writers, and Seneca is similarly mentioned by Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

. In the 6th century Martin of Braga

Martin of Braga (in Latin ''Martinus Bracarensis'', in Portuguese, known as ''Martinho de Dume'' 520–580 AD) was an archbishop of Bracara Augusta in Gallaecia (now Braga in Portugal), a missionary, a monastic founder, and an ecclesiasti ...

synthesized Seneca's thought into a couple of treatises that became popular in their own right. Otherwise, Seneca was mainly known through a large number of quotes and extracts in the ''florilegia

In medieval Latin, a ' (plural ') was a compilation of excerpts or sententia from other writings and is an offshoot of the commonplacing tradition. The word is from the Latin ''flos'' (flower) and '' legere'' (to gather): literally a gathering of ...

'', which were popular throughout the medieval period. When his writings were read in the later Middle Ages, it was mostly his '' Letters to Lucilius''—the longer essays and plays being relatively unknown.

Medieval writers and works continued to link him to Christianity because of his alleged association with Paul. The '' Golden Legend'', a 13th-century hagiographical account of famous saints that was widely read, included an account of Seneca's death scene, and erroneously presented Nero as a witness to Seneca's suicide. Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

placed Seneca (alongside Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

) among the "great spirits" in the First Circle of Hell

The first circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem ''Inferno (Dante), Inferno'', the first part of the ''Divine Comedy''. ''Inferno'' tells the story of Dante's imaginary journey through a vision of the Hell in Christia ...

, or Limbo. Boccaccio, who in 1370 came across the works of Tacitus whilst browsing the library at Montecassino, wrote an account of Seneca's suicide hinting that it was a kind of disguised baptism, or a ''de facto'' baptism in spirit. Some, such as Albertino Mussato and Giovanni Colonna, went even further and concluded that Seneca must have been a Christian convert.

An improving reputation

Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

, but also in Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

and to a large degree in Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credite ...

, who adopted his style in his own essays and who quotes him more than any other authority except Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

. In the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, printed editions and translations of his works became common, including an edition by Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

and a commentary by John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

.Richard Mott Gummere, ''Seneca the philosopher, and his modern message'', p. 97. John of Salisbury, Erasmus and others celebrated his works. French essayist Montaigne, who gave a spirited defense of Seneca and Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

in his ''Essays'', was himself considered by Pasquier a "French Seneca". Similarly, Thomas Fuller

Thomas Fuller (baptised 19 June 1608 – 16 August 1661) was an English churchman and historian. He is now remembered for his writings, particularly his ''Worthies of England'', published in 1662, after his death. He was a prolific author, and ...

praised Joseph Hall as "our English Seneca". Many who considered his ideas not particularly original still argued that he was important in making the Greek philosophers presentable and intelligible. His suicide has also been a popular subject in art, from Jacques-Louis David's 1773 painting '' The Death of Seneca'' to the 1951 film ''Quo Vadis

''Quō vādis?'' (, ) is a Latin phrase meaning "Where are you marching?". It is also commonly translated as "Where are you going?" or, poetically, "Whither goest thou?"

The phrase originates from the Christian tradition regarding Saint Pet ...

''.

Even with the admiration of an earlier group of intellectual stalwarts, Seneca has never been without his detractors. In his own time, he was accused of hypocrisy or, at least, a less than "Stoic" lifestyle. While banished to Corsica, he wrote a plea for restoration rather incompatible with his advocacy of a simple life and the acceptance of fate. In his '' Apocolocyntosis'' he ridiculed the behaviors and policies of Claudius, and flattered Nero—such as proclaiming that Nero would live longer and be wiser than the legendary Nestor

Nestor may refer to:

* Nestor (mythology), King of Pylos in Greek mythology

Arts and entertainment

* "Nestor" (''Ulysses'' episode) an episode in James Joyce's novel ''Ulysses''

* Nestor Studios, first-ever motion picture studio in Hollywood, L ...

. The claims of Publius Suillius Rufus

Publius may refer to:

Roman name

* Publius (praenomen)

* Ancient Romans with the name:

** Publius Valerius Publicola (died 503 BC), Roman consul, co-founder of the Republic

** Publius Clodius Pulcher (c. 93 BC – 52 BC), Republican politicia ...

that Seneca acquired some "three hundred million '' sesterces''" through Nero's favor are highly partisan, but they reflect the reality that Seneca was both powerful and wealthy. Robin Campbell, a translator of Seneca's letters, writes that the "stock criticism of Seneca right down the centuries as been..the apparent contrast between his philosophical teachings and his practice."

In 1562 Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano (; also Girolamo or Geronimo; french: link=no, Jérôme Cardan; la, Hieronymus Cardanus; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath, whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, ...

wrote an ''apology'' praising Nero in his ''Encomium Neronis'', printed in Basel. This was likely intended as a mock ''encomium

''Encomium'' is a Latin word deriving from the Ancient Greek ''enkomion'' (), meaning "the praise of a person or thing." Another Latin equivalent is ''laudatio'', a speech in praise of someone or something.

Originally was the song sung by the c ...

'', inverting the portrayal of Nero and Seneca that appears in Tacitus. In this work Cardano portrayed Seneca as a crook of the worst kind, an empty rhetorician who was only thinking to grab money and power, after having poisoned the mind of the young emperor. Cardano stated that Seneca well deserved death.

"We are therefore left with no contemporary record of Seneca's life, save for the desperate opinion of Publius Suillius. Think of the barren image we should have ofMore recent work is changing the dominant perception of Seneca as a mere conduit for pre-existing ideas, showing originality in Seneca's contribution to the history of ideas. Examination of Seneca's life and thought in relation to contemporary education and to the psychology of emotions is revealing the relevance of his thought. For example, Martha Nussbaum in her discussion of desire and emotion includes Seneca among the Stoics who offered important insights and perspectives on emotions and their role in our lives. Specifically devoting a chapter to his treatment of anger and its management, she shows Seneca's appreciation of the damaging role of uncontrolled anger, and its pathological connections. Nussbaum later extended her examination to Seneca's contribution toSocrates Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ..., had the works ofPlato Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...andXenophon Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...not come down to us and were we wholly dependent uponAristophanes Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his fo ...' description of this Athenian philosopher. To be sure, we should have a highly distorted, misconstrued view. Such is the view left to us of Seneca, if we were to rely upon Suillius alone."

political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

showing considerable subtlety and richness in his thoughts about politics, education, and notions of global citizenship—and finding a basis for reform-minded education in Seneca's ideas she used to propose a mode of modern education that avoids both narrow traditionalism and total rejection of tradition. Elsewhere Seneca has been noted as the first great Western thinker on the complex nature and role of gratitude in human relationships.

Notable fictional portrayals

Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is conside ...

's 1642 opera '' L'incoronazione di Poppea'' (''The Coronation of Poppea''), which is based on the pseudo-Senecan play, '' Octavia''. In Nathaniel Lee's 1675 play ''Nero, Emperor of Rome'', Seneca attempts to dissuade Nero from his egomaniacal plans, but is dragged off to prison, dying off-stage. He appears in Robert Bridges' verse drama ''Nero'', the second part of which (published 1894) culminates in Seneca's death. Seneca appears in a fairly minor role in Henryk Sienkiewicz's 1896 novel ''Quo Vadis

''Quō vādis?'' (, ) is a Latin phrase meaning "Where are you marching?". It is also commonly translated as "Where are you going?" or, poetically, "Whither goest thou?"

The phrase originates from the Christian tradition regarding Saint Pet ...

'' and was played by Nicholas Hannen in the 1951 film. In Robert Graves's 1934 book '' Claudius the God'', the sequel novel to ''I, Claudius

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the R ...

'', Seneca is portrayed as an unbearable sycophant. He is shown as a flatterer who converts to Stoicism solely to appease Claudius's own ideology. The "Pumpkinification" (''Apocolocyntosis'') to Graves thus becomes an unbearable work of flattery to the loathsome Nero, mocking a man that Seneca groveled to for years. The historical novel ''Chariot of the Soul'' by Linda Proud features Seneca as tutor of the young Togidubnus, son of King Verica of the Atrebates, during his ten-year stay in Rome.

See also

*Audio theater

Radio drama (or audio drama, audio play, radio play, radio theatre, or audio theatre) is a dramatized, purely acoustic performance. With no visual component, radio drama depends on dialogue, music and sound effects to help the listener imagine ...

* Glossarium Eroticum

Glossarium Eroticum is a Latin-language dictionary of sexual words and phrases, and of many pertaining to the human body or considered to be obscene, by Pierre-Emmanuel Pierrugues, published in 1826. It lists definitions and excerpts Old Latin a ...

* Otium

''Otium'', a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome ...

* Seneca (crater)

Seneca is a lunar impact crater that is located towards the east-northeastern limb, less than one crater diameter to the north of Plutarch. To the northwest is the crater Hahn, and due north lies the large walled plain Gauss.

This crater has been ...

* 2608 Seneca

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. ''Anger, Mercy, Revenge.'' trans. Robert A. Kast and Martha C. Nussbaum. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2010. * Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. ''Hardship and Happiness.'' trans. Elaine Fantham, Harry M. Hine, James Ker, and Gareth D. Williams. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2014. * Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. ''Natural Questions.'' trans. Harry M. Hine. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2010. * Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. ''On Benefits.'' trans. Miriam Griffin and Brad Inwood. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2011. * Seneca: ''The Tragedies.'' Various translators, ed. David R. Slavitt. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols, 1992–94. * Seneca: ''Tragedies.'' Ed. & transl. John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 2 vols, 2nd edn. 2018. * Cunnally, John, “Nero, Seneca, and the Medallist of the Roman Emperors”, ''Art Bulletin'', Vol. 68, No. 2 (June 1986), pp. 314–317 * Di Paola, O. (2015)"Connections between Seneca and Platonism in Epistulae ad Lucilium 58"

Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: PHI2015-1445. * Fitch, John G. (ed), ''Seneca.'' Oxford University Press, 2008. . A collection of essays by leading scholars. * * Griffin, Miriam T., ''Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics.'' Oxford University Press, 1976. . Still the standard biography. * Inwood, Brad, ''Reading Seneca. Stoic Philosophy at Rome'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. * Lucas, F. L.

''Seneca and Elizabethan Tragedy''

(Cambridge University Press, 1922; paperback 2009, ); on Seneca the man, his plays, and the influence of his tragedies on later drama.

Mitchell, David. ''Legacy: The Apocryphal Correspondence between Seneca and Paul''

Xlibris Corporation 2010 * Motto, Anna Lydia

”Seneca on Death and Immortality“

''The Classical Journal'', Vol. 50, No. 4 (Jan. 1955), pp. 187–189 * Motto, Anna Lydia

"Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic"

''The Classical Journal'', Vol. 61, No. 6 (March 1966), pp. 254–258

Sevenster, J.N.

''Paul and Seneca''

Novum Testamentum, Supplements

Vol. 4, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1961; a comparison of Seneca and the apostle Paul, who were contemporaries.

Shelton, Jo-Ann

Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978. . A revision of the author's doctoral thesis at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, 1974.

* Wilson, Emily, ''Seneca: Six Tragedies.'' Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press, 2010.

External links

*Works by Seneca the Younger at Perseus Digital Library

* * * Original texts of Seneca's works a

* * * *

Collection of works of Seneca the Younger at Wikisource

* ttp://www.curculio.org/Seneca/em-list.html List of commentaries of Seneca's Letters

Incunabula (1478) of Seneca's works in the McCune Collection

, read by Katharina Volk, Columbia University. Society for the Oral reading of Greek and Latin Literature (SORGLL)

Digitized works by Lucius Annaeus Seneca

at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España

Guide to Seneca, Lucius Annaeus, Spurious works. Manuscript, ca. 1450

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

Digitized Edition of Seneca's Opera Omnia from 1503

(Venice) a

E-rara.ch

{{Authority control 0s BC births Year of birth uncertain 65 deaths 1st-century executions 1st-century philosophers 1st-century Romans 1st-century writers Ancient Roman tragic dramatists Ancient Romans who committed suicide Annaei Ethicists Executed philosophers Executed writers Forced suicides Latin letter writers Literary theorists Male dramatists and playwrights Male essayists Male poets Members of the Pisonian conspiracy Moral philosophers People executed by the Roman Empire People from Córdoba, Spain Philosophers of art Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of mind Philosophers of social science Philosophers of Roman Italy Political philosophers Roman encyclopedists Roman-era historians Roman-era philosophers Roman-era satirists Roman-era Stoic philosophers Romans from Hispania Silver Age Latin writers Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome