Hobart and William Smith Colleges are

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

liberal arts college

A liberal arts college or liberal arts institution of higher education is a college with an emphasis on undergraduate study in liberal arts and sciences. Such colleges aim to impart a broad general knowledge and develop general intellectual capac ...

s in

Geneva, New York

Geneva is a City (New York), city in Ontario County, New York, Ontario and Seneca County, New York, Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake (New York), Seneca Lake; all land port ...

. They trace their origins to Geneva Academy established in 1797. Students can choose from 45 majors and 68 minors with degrees in

Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

,

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

, Master of Arts in Teaching, Master of Science in Management, and Master of Arts in Higher Education Leadership. It is associated with 35

Fulbright Scholars

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

, 3

Rhodes Scholars

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, and numerous

Marshall Scholars

The Marshall Scholarship is a postgraduate scholarship for "intellectually distinguished young Americans ndtheir country's future leaders" to study at any university in the United Kingdom. It is widely considered one of the most prestigious sc ...

,

Rangel Fellows,

Truman Scholars

The Harry S. Truman Scholarship is the premier graduate fellowship in the United States for public service leadership. It is a federally funded scholarship granted to U.S. undergraduate students for demonstrated leadership potential, academic ...

,

Emmy

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

, and

Pulitzer Pulitzer may refer to:

*Joseph Pulitzer, a 20th century media magnate

*Pulitzer Prize, an annual U.S. journalism, literary, and music award

*Pulitzer (surname)

* Pulitzer, Inc., a U.S. newspaper chain

*Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, a non-pro ...

awardees as well as United States senators, House representatives, and a

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

justice. Hobart and William Smith Colleges is a member of the New York Six Liberal Arts Consortium, an association of highly selective liberal arts colleges. It is frequently ranked among the top 100 liberal arts colleges in the United States.

The colleges were originally separate institutions – Hobart College for men and William Smith College for women – that shared close bonds and a contiguous campus. Founded as Geneva College in 1822, Hobart College was renamed in honor of its founder

John Henry Hobart

John Henry Hobart (September 14, 1775 – September 12, 1830) was the third Episcopal bishop of New York (1816–1830). He vigorously promoted the extension of the Episcopal Church in upstate New York, as well as founded both the General Th ...

, bishop of

Episcopal Diocese of New York

The Episcopal Diocese of New York is a diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, encompassing three New York City boroughs and seven New York state counties. in 1852. William Smith College was founded in 1908 by Geneva philanthropist and nurseryman William Smith at the suggestion of numerous suffragettes and activists including

Elizabeth Smith Miller

Elizabeth Smith Miller ( Smith; September 20, 1822 – May 23, 1911), known as "Libby", was an American advocate and financial supporter of the women's rights movement.NY History Net (April 21, 2011).

Biography

Elizabeth Smith was born Septembe ...

and her daughter Anne Fitzhugh Miller. In 1943, William Smith College was elevated from its original status as a department of Hobart College to an independent college and the two colleges established a joint corporate identity. They are officially chartered as "Hobart and William Smith Colleges" and informally referred to as "HWS" or "the Colleges." Although united in one corporation with many shared resources and overlapping organization, they have each retained their own traditions.

Today, students are free to participate in each of the colleges' customs and traditions based on their preferred gender identities. Students can graduate with diplomas issued by Hobart College, William Smith College, or Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

History

Hobart and William Smith Colleges, private colleges in Geneva, New York, began on the western frontier as the Geneva Academy. After some setbacks and disagreement among trustees, the academy suspended operations in 1817. By the time Bishop

John Henry Hobart

John Henry Hobart (September 14, 1775 – September 12, 1830) was the third Episcopal bishop of New York (1816–1830). He vigorously promoted the extension of the Episcopal Church in upstate New York, as well as founded both the General Th ...

, of the

Episcopal Diocese of New York

The Episcopal Diocese of New York is a diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, encompassing three New York City boroughs and seven New York state counties. , first visited the city of Geneva in 1818, the doors of Geneva Academy had just closed. Yet, Geneva was a bustling

Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

city on the main land and stage coach route to the West. Bishop Hobart had a plan to reopen the academy at a new location, raise a public subscription for the construction of a stone building, and elevate the school to college status. Roughly following this plan, Geneva Academy reopened as Geneva College in 1822 with conditional grant funds made available from

Trinity Church in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Geneva College was renamed Hobart College in 1852 in honor of its founder, Bishop Hobart.

William Smith College was founded in 1908, originally as William Smith College for Women. Its namesake and founder was a wealthy local nurseryman, benefactor of the arts and sciences, and philanthropist. The school arose from negotiations between William Smith, who sought to establish a women's college, and Hobart College President Langdon C. Stewardson, who sought to redirect Smith's philanthropy towards Hobart College. Smith, however, was intent on establishing a coordinate, nonsectarian women's college, which, when realized, coincidentally gave Hobart access to new facilities and professors. The two student bodies were educated separately in the early years, even though William Smith College was a department of Hobart College for organizational purposes until 1943. That year, after a gradual relaxation of academic separation, William Smith College was formally recognized as an independent college, co-equal with Hobart. Both colleges were reflected in a new, joint corporate identity.

Early history and growth

Geneva Academy

Geneva Academy was founded in 1796 when Geneva was just a small frontier settlement. It is believed to be the first school formed in Geneva.

The area was considered "the gateway to Genesee County" and was in the early stages of development from the wilderness.

In 1809, the trustees of the academy appointed Rev. Andrew Wilson, formerly of the

University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

in Scotland as head of the school.

He remained until 1812 when Ransom Hubell, a graduate of

Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

, was made principal.

Geneva College

The Regents granted the full charter on February 8, 1825, and at that time, Geneva Academy officially changed its name to Geneva College.

Rev. J. Adams was president of the college as of 1827.

The "English Course," as it was known, was a radical departure from long established educational usage and represented the beginning of the college work pattern found today.

Geneva Medical College

Geneva Medical College was founded on September 15, 1834, as a separate department of Geneva College. The medical school was founded by

Edward Cutbush, who also served as the first dean for the school.

Elizabeth Blackwell

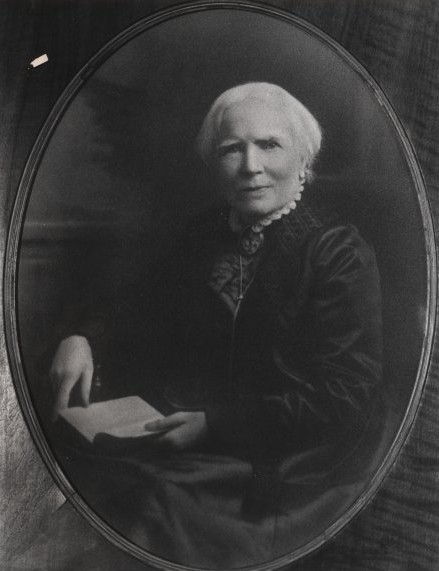

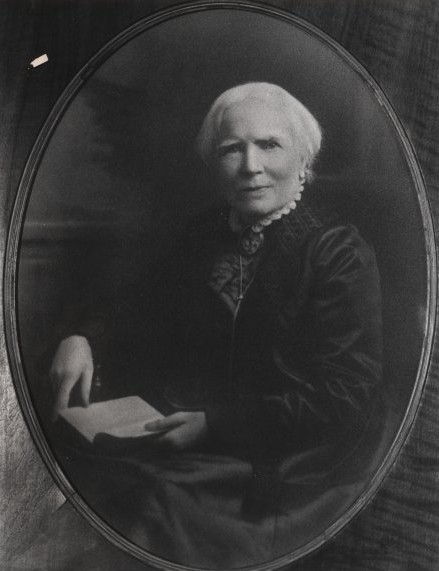

In an era when the prevailing conventional wisdom was no woman could withstand the intellectual and emotional rigors of a medical education,

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell (3 February 182131 May 1910) was a British physician, notable as the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and the first woman on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council for the United Ki ...

, (1821–1910) applied to and was rejected – or simply ignored – by 29 medical schools before being admitted in 1847 to the Medical Institution of Geneva College.

The medical faculty, largely opposed to her admission but seemingly unwilling to take responsibility for the decision, decided to submit the matter to a vote of the students. The men of the college voted to admit her.

Blackwell graduated two years later, on January 23, 1849, at the top of her class to become the first woman doctor in the Northern hemisphere.

"The occasion marked the culmination of years of trial and disappointment for Miss Blackwell, and was a key event in the struggle for the emancipation of women in the nineteenth century in America."

Blackwell went on to found the

New York Infirmary for Women and Children

NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital is a nonprofit, Acute (medicine), acute care, teaching hospital in New York City and is the only hospital in Lower Manhattan south of Greenwich Village. It is part of the NewYork-Presbyterian Healthca ...

and had a role in the creation of its medical college.

She then returned to her native England and helped found the

National Health Society

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

and taught at the first college of medicine for women to be established there.

Hobart College

The school was known as Geneva College until 1852, when it was renamed in memory of its most forceful advocate and founder, Bishop Hobart, to Hobart Free College. In 1860, the name was shortened to Hobart College.

Hobart College of the 19th century was the first American institution of higher learning to establish a three-year "English Course" of study to educate young men destined for such practical occupations as "journalism, agriculture, merchandise, mechanism, and manufacturing", while at the same time maintaining a traditional four-year "classical course" for those intending to enter "the learned professions." It also was the first college in America to have a dean of the college.

Notable 19th-century alumni included

Albert James Myer

Albert James Myer (September 20, 1828 – August 24, 1880) was a surgeon and United States Army general. He is known as the father of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, as its first chief signal officer just prior to the American Civil War, the inventor ...

, Class of 1847, a military officer assigned to run the

United States Weather Bureau

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an agency of the United States federal government that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weather-related products to organizations and the public for the ...

at its inception, was a founding member of the

International Meteorological Organization

The International Meteorological Organization (IMO; 1873–1951) was the first organization formed with the purpose of exchanging weather information among the countries of the world. It came into existence from the realization that weather systems ...

, and helped birth the

U.S. Signal Corps

)

, colors = Orange and white

, colors_label = Corps colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

...

, and for whom

Fort Myer, Virginia

Fort Myer is the previous name used for a U.S. Army post next to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, and across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Founded during the American Civil War as Fort Cass and Fort Whipple, t ...

, is named; General

E. S. Bragg of the Class of 1848, colonel of the Sixth Wisconsin Regiment and a brigadier general in command of the

Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought ent ...

who served one term in Congress and later was ambassador to Mexico and consul general of the U.S. in Cuba; two other 1848 graduates,

Clarence A. Seward Clarence may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Clarence County, New South Wales, a Cadastral division

* Clarence, New South Wales, a place near Lithgow

* Clarence River (New South Wales)

* Clarence Strait (Northern Territory)

* City of Clarence, a loca ...

and Thomas M. Griffith, who were assistant secretary of state and builder of the first national railroad across the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, respectively; and

Charles J. Folger, Class of 1836, a

United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

in the 1880s.

Until the mid-20th century, Hobart was strongly affiliated with the

Episcopal Church and produced many of its clergy. While this affiliation continues to the present, the last Episcopal clergyman to serve as President of Hobart (1956–1966) was Louis Melbourne Hirshson. Since then, the president of the colleges has been a layperson.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Hobart College was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the

V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

which offered students a path to a Navy commission.

Founding of William Smith College

Toward the end of the 19th century, Hobart College was on the brink of bankruptcy. It was through the presidency of Langdon Stewardson the college obtained a new donor, nurseryman William Smith. Smith had built the Smith Opera House in downtown Geneva and the Smith Observatory on his property when he became interested in founding a college for women, a plan he pursued to the point of breaking ground before realizing it was beyond his means. As publicized in The College Signal on October 7, 1903, "William Smith, a millionaire nurseryman, will found and endow a college for women at Geneva, N. Y., to be known as the William Smith College for Women The institution will be in the most beautiful section. One building is to cost $150,000. Mr. Smith maintains the Smith observatory there." In 1903, Hobart College President Langdon C. Stewardson learned of Smith's interest and, for two years, attempted to convince him to make Hobart College the object of his philanthropy. With enrollments down and its resources strained, Hobart's future depended upon an infusion of new funds.

Unable to convince Smith to provide direct assistance to Hobart, President Stewardson redirected the negotiations toward founding a coordinate institution for women, a plan that appealed to the

philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

. On December 13, 1906, he formalized his intentions; two years later William Smith School for Women – a coordinate, nonsectarian women's college – enrolled its first class of 18 students. That charter class grew to 20 members before its graduation in 1912.

In addition, Smith's gift made possible construction of the Smith Hall of Science, to be used by both colleges, and permitted the hiring, also in 1908, of three new faculty members who would teach in areas previously unavailable in the curriculum: biology, sociology, and psychology.

World War II

Between 1943 and 1945, Hobart College trained almost 1,000 men in the U.S. Navy's

V-12 program, many of whom returned to complete their college educations when the post-World War II GI Bill swelled the enrollments of American colleges and universities. In 1948, three of those veterans –

William F. Scandling, Harry W. Anderson, and W. P. Laughlin – took over operation of the Hobart dining hall. Their fledgling business was expanded the next year to include William Smith College; after their graduation, in 1949, it grew to serve other colleges and universities across the country, eventually becoming

Saga Corporation

William F. "Bill" Scandling (June 17, 1922 – August 22, 2005) was an American businessman and philanthropist who was one of the founders of Saga Corporation, a multi-billion dollar food service and restaurant company.http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir ...

, a nationwide provider of institutional food services.

Campus

Layout

Hobart and William Smith Colleges' campus is situated on in

Geneva, New York

Geneva is a City (New York), city in Ontario County, New York, Ontario and Seneca County, New York, Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake (New York), Seneca Lake; all land port ...

, along the shore of

Seneca Lake, the largest of the

Finger Lakes

The Finger Lakes are a group of eleven long, narrow, roughly north–south lakes located south of Lake Ontario in an area called the ''Finger Lakes region'' in New York, in the United States. This region straddles the northern and transitional ...

. The campus is notable for the style of Jacobean Gothic architecture represented by many of its buildings, notably Coxe Hall, which houses the President's Office and other administrative departments. In contrast, the earliest buildings were built in the Federal style and the chapel is Neo-Gothic.

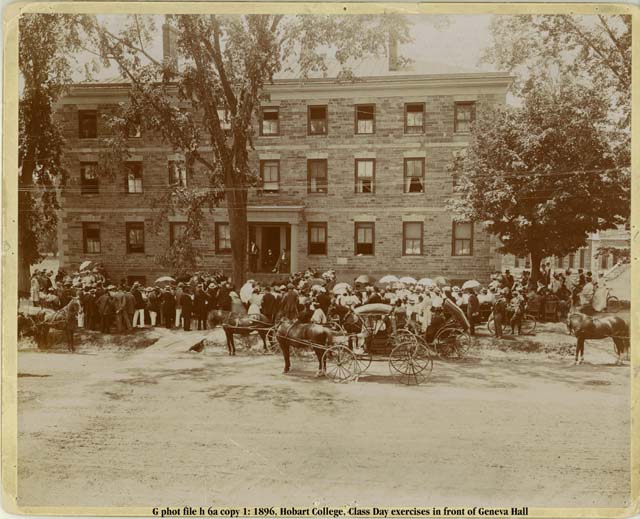

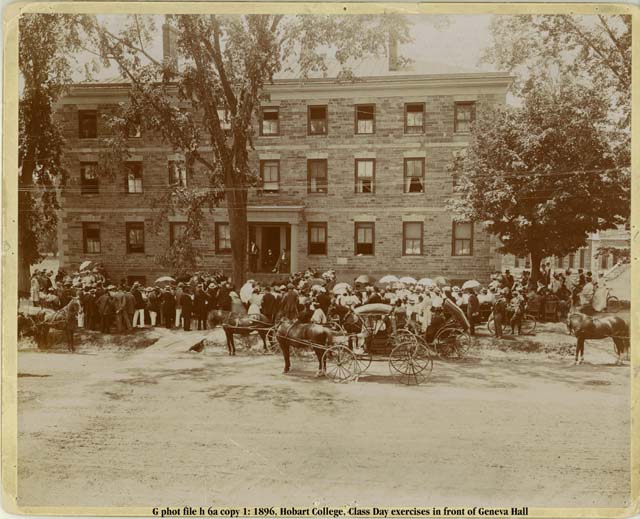

The Quad, the core of the Hobart campus, was formed by the construction of Medbery, Coxe, and Demarest. Several years later, Arthur Nash, a Hobart professor, designed Williams Hall, which would be constructed in the gap between Medbery and Coxe. The Quad is formed to the east by Trinity and Geneva Hall, the two original College buildings, and to the south by the Science compound, and Napier Hall.

Geneva Hall (1822) and Trinity Hall (1837) were added to the

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1973.

In 2016, the schools announced they were going solar by building two solar farms to create enough electricity for about 50 percent of HWS' needs.

The Hill (or William Smith Hill) is a prominent feature of the historic William Smith campus. Located at the top of a large sloping hill to the West of Seneca Lake and the Hobart Quad, the Hill houses three historic William Smith dorms, and one built in the 1960s (Comstock, Miller, Blackwell, and Hirshson Houses). At its peak resides William Smith's all female dorms. The Hill was the site originally conceived for William Smith College. Unveiled in 2008 for the William Smith Centennial is a statue of the college's founder and benefactor, William Smith.

A 15 million dollar expansion of the Scandling Campus Center was completed in autumn 2008. This renovation added over 17,000 additional square feet, including an expanded cafe, a new post office, and more meeting areas. In 2016 the Gearan Center for Performing Arts was completed at a cost of 28 million dollars; the largest project in the history of the colleges.

Key buildings

Coxe Hall, serves as the main administrative hub of campus. Constructed in 1901, the building is named after Bishop Arthur Clevland Coxe, a benefactor of the school, and houses the president's office, Bartlett Theater, The Pub, and a classroom wing, which was added in the 1920s. Arthur Cleveland Coxe was closely affiliated with the school. The building was designed by

Clinton and Russell

Clinton and Russell was a well-known architectural firm founded in 1894 in New York City, United States. The firm was responsible for several New York City buildings, including some in Lower Manhattan.

Biography

Charles W. Clinton (1838– ...

Architects.

Gearan Center for the Performing Arts, named in honor of President Mark D Gearan and Mary Herlihy Gearan, was in 2016. It includes a lobby that links three flexible performance and rehearsal spaces for theater, music and dance. Also included are faculty offices, practice and recital rooms and a film screening room.

Scandling Campus Center, named after

William F. Scandling '49, renovated and expanded in 2009, houses Saga (the dining hall), the post office, offices of student activities, a cafe, and Vandervort room (a large event space).

Gulick Hall, was built in 1951 as part of the post-war "mini-boom" that also included the construction of the Hobart "mini-quad" dormitories Durfee, Bartlett, and Hale (each named for a 19th-century Hobart College president). Gulick Hall originally housed the campus dining services and, later, the Office of the Registrar. Completely renovated in 1991, Gulick now houses both the Office of the Registrar and the Psychology department, which was moved from Smith Hall in 1991 prior to its renovation in 1992.

Stern Hall, named for the lead donor, Herbert J. Stern '58, was completed in 2004. It houses the departments of economics, political science, anthropology & sociology, environmental studies and Asian languages and cultures.

Smith Hall, built in 1907, originally housed both the Biology and Psychology Departments. It is now home to the Dean's Offices of both colleges, along with the departmental offices of Writing and Rhetoric and the various modern language departments. Smith Hall was the first building constructed with funds from William Smith on the William Smith College campus, but it is also the first building that has always been shared by both colleges.

Williams Hall, completed in 1907, housed the first campus gymnasium and, after the construction of Bristol gymnasium, served several other lives as campus post office, book store, IT services and location of the Music Department.

Demarest Hall, connected to St. John's Chapel by St. Mark's Tower, houses the departments of Religious Studies and English and Comparative Literature as well as the Women's Studies Program. Also home to the Blackwell Room, named in honor of Elizabeth Blackwell (once used as study area and library, the space is now used for classrooms in the absence of more intentional planning for classroom space), Demarest was designed by

Richard Upjohn

Richard Upjohn (22 January 1802 – 16 August 1878) was a British-born American architect who emigrated to the United States and became most famous for his Gothic Revival churches. He was partially responsible for launching the movement to su ...

's son, Richard M. Upjohn. (Upjohn's grandson,

Hobart Upjohn

Hobart Brown Upjohn (1876–1949) was an American architect, best known for designing a number of ecclesiastical and educational structures in New York and in North Carolina. He also designed a number of significant private homes. His firm produce ...

would design several of the college's buildings as well). Demarest served as the college's library until the construction of the Warren Hunting Smith Library in the early 1970s. In the 1960s it was expanded to hold the college's growing number of volumes. Today, it also houses the Fisher Center for the Study of Gender and Justice, an intellectual center led by such scholar faculty as Dunbar Moodie (Sociology), Betty Bayer (Women's Studies), and Jodi Dean (Political Science).

Trinity Hall built in 1837, was the second of the colleges' buildings. Trinity Hall was designed by college president Benjamin Hale, who taught architecture. Trinity served as a dormitory and a library, but it was converted into a space for classrooms, labs, and offices later in the 19th century. It presently is home to the Salisbury Center for Career Services.

Merrit Hall, completed in 1879, was built on the ruins of the old medical college. Merrit was the first science building on campus and housed the chemistry labs. Merrit also housed a clock atop the quad side of the building. On the eve of the Hobart centennial in 1922, students climbed to the top and made the bell strike 100 times. Merrit Hall was also one of the first buildings shared by Hobart and William Smith. Today Merrit Hall houses a lecture hall and faculty offices.

St. John's Chapel, designed by

Richard Upjohn

Richard Upjohn (22 January 1802 – 16 August 1878) was a British-born American architect who emigrated to the United States and became most famous for his Gothic Revival churches. He was partially responsible for launching the movement to su ...

the architect of

Trinity Church in New York City, served as the religious hub of the campus, replacing Polynomous, the original campus chapel. In the 1960s, St. John's was connected to Demarest Hall by St. Marks Tower.

Houghton House, the mansion, known for its Victorian elements, is home to the Art and Architecture departments. The country mansion was built, in the 1880s by

William J. King. It was purchased in 1901 by the wife of Charles Vail (maiden name Helen Houghton), Hobart graduate and professor, as the family's summer home. Mrs. Vail remodeled the Victorian mansion's interior to the present classical decor in 1913. The family's "town home" is 624 S. Main Street and is now the Sigma Phi fraternity. Helen Vail's heirs donated the house and its grounds to the colleges to be used as a woman's dormitory. After many years as a student dorm, the house became home to the art department after the original art studio was razed to make way for the new Scandling Campus Center. The building is now home to the Davis Art Gallery, with lecture rooms, multiple faculty offices, and architecture studios on the top floor.

Katherine D. Elliot Hall, was constructed in 2006. The "Elliot" houses contains art classrooms; offices; studios for painting, photography, and printing; and wood and metal shops.

Goldstein Family Carriage House, was built by William J. King in 1882 and was renovated in 2006 to house a digital imaging lab and a photo studio with a darkroom for black-and-white photography.

Warren Hunting Smith Library, in the center of the campus, houses 385,000 volumes, 12,000 periodicals, and more than 8,000 VHS and DVD videos. In 1997, the library underwent a major renovation, undergoing several improvements, such as the addition of multimedia centers, and the addition to its south side of the L. Thomas Melly Academic Center, a spacious, modern location for "round the clock" study.

Napier Hall, attached to the Rosenberg Hall, houses several classrooms and was completed in 1994.

Rosenberg Hall, named for Henry A. Rosenberg (Hobart '52), is an annex of Lansing and Eaton Hall, the original science buildings. Rosenberg houses many labs and offices.

Lansing Hall, built in 1954, is home to Sciences and Mathematics. The building is named for John Ernest Lansing, Professor of Chemistry (1905–1948), who twice served as acting president.

Eaton Hall, is named for

Elon Howard Eaton

Elon Howard Eaton (sometimes Elon Eton; 8 October 1866 – 27 March 1934) was an American ornithologist, scholar, and author.

He was born in the Town of Collins near Springville, New York, the son of Luzerne Eaton and Sophie Newton. As a youth, ...

, Professor of Biology (1908–1935). Eaton, one of New York's outstanding ornithologists, was one of the professors brought to campus with William Smith grant funds. Eaton Hall is a part of the science complex at the south end of the Hobart Quad, which consists of Lansing, Rosenberg, and Napier.

Dormitories

Men's dorms

Geneva Hall, built in 1822, is the college's first building, and the cornerstone site designated by the School's founder, Bishop

John Henry Hobart

John Henry Hobart (September 14, 1775 – September 12, 1830) was the third Episcopal bishop of New York (1816–1830). He vigorously promoted the extension of the Episcopal Church in upstate New York, as well as founded both the General Th ...

. The building is one of the oldest academic building in continuous use, having served as a dormitory, among other uses, since its completion. The building has inscribed into its quoins, and alongside the perimeter of its facade, plaques which list the graduates of classes dating back to the 19th century.

The Mini Quad, consisting of three buildings, Durfee, Hale, and Bartlett, houses about 150 Hobart students. Since the 2006 academic year, the dorms have become coeducational, with at least one floor housing William Smith Students.

Hale Hall is named for Benjamin Hale, president of Hobart College from 1836 to 1858.

Bartlett Hall was named after the Reverend Murray Bartlett, who served as fourteenth president of Hobart College from 1919 to 1936

Durfee Hall was named after

William Pitt Durfee

William Pitt Durfee (5 February 1855 – 17 December 1941) was an American mathematician who introduced Durfee square

In number theory, a Durfee square is an attribute of an integer partition. A partition of ''n'' has a Durfee square of size ''s' ...

, who from 1884 to 1929 served as Professor of Mathematics and Chair of the Mathematics Department. He was the first dean of a liberal arts college and served as acting president of the Colleges four times.

Women's dorms

Blackwell House was designed and built in 1860 by

Richard Upjohn

Richard Upjohn (22 January 1802 – 16 August 1878) was a British-born American architect who emigrated to the United States and became most famous for his Gothic Revival churches. He was partially responsible for launching the movement to su ...

as a residence for William Douglass, who served as a trustee of Hobart College. The house was purchased in 1908 as the first William Smith dormitory. The house still houses William Smith students and is known for its grand Victorian features from fireplaces, to chandeliers, to large old windows. Though rarely recognized as such, the house is named for Elizabeth Blackwell, an early graduate of what became the Colleges.

Comstock House was designed by

Richard Upjohn

Richard Upjohn (22 January 1802 – 16 August 1878) was a British-born American architect who emigrated to the United States and became most famous for his Gothic Revival churches. He was partially responsible for launching the movement to su ...

's grandson, Hobart Upjohn, in 1932. Comstock is a women's dormitory named for Anna Botsford Comstock, friend of William Smith and the first woman to be named a member of the board of trustees.

Miller House was William Smith College's second dormitory. Miller was designed by Arthur Nash, professor and grandson of Arthur Cleveland Coxe. Nash also designed Smith Hall and Williams Hall. This house honors Elizabeth Smith Miller, a leader in the women's movement.

Hirshson House, completed in 1962, was named for the president of the colleges, Louis Melbourne Hirshson, the last Episcopal clergy person to serve in that capacity. The building is home to William Smith students.

Coed dorms

Medbery Hall is an original Hobart College dorm dating from the 1900. Medbery defines the right side of the Hobart Quadrangle. Designed by

Clinton and Russell

Clinton and Russell was a well-known architectural firm founded in 1894 in New York City, United States. The firm was responsible for several New York City buildings, including some in Lower Manhattan.

Biography

Charles W. Clinton (1838– ...

architects at the same time as Coxe Hall, the two buildings share similarity in their Jacobean Gothic style. Medbery is adorned with a recognizable Flemish roofline. Medbery was designed without long hallways "conductive to rioting" and mischief, such as rolling a cannonball down the hallway. Such mischief was experienced in the other two dormitories on campus, Geneva and Trinity Halls.

Jackson, Potter, Rees, together known as JPR for short (and once dubbed "superdorm"), the three identical buildings create their own quad in the south end of campus. The dorms were built in 1966 and are named after various historical figures of Hobart College. The complex houses about 230 first-year and upper class Hobart and William Smith students. The building was completely renovated in 2005 to include quad living spaces (two double bed rooms connected by a common living room) and open lounge spaces and lounges on every floor.

Jackson Hall is named for Abner Jackson, president of the Hobart in the middle of the 19th century. Jackson would go on to become president of

Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

in Connecticut, where he would be the principal designer of its present campus.

Rees Hall is named for Major James Rees, an early settler and landowner in Geneva and an acquaintance of George Washington.

Potter Hall is named for John Milton Potter, President of Hobart and William Smith Colleges from 1942 to 1947.

The Village at Odell's Pond is a collection of apartment style dorms available to upperclassmen at the colleges. The units have either four or five bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, a living room and a kitchen.

Emerson Hall was built in 1969. The rooms are designed as suites, with two doubles and two singles and a common living room and bathroom.

Caird Hall was built, along with deCordova, in 2005. The dorm has provisions for singles, doubles, and quads, and is often desired by students due to the separate temperature controls in each room. The ground floor hosts a lounge area with both gaming and fitness equipment for students.

deCordova Hall was built, along with Caird, in 2005. The dorm has provisions for singles, doubles, and quads, and is often desired by students due to the separate temperature controls in each room. The ground floor has a lounge area for students, as well as the deCordova cafe.

The surrounding ecosystem plays a major role in the Colleges' curriculum and acquisitions. The Colleges own the Hanley Biological Field Station and Preserve on neighboring

Cayuga Lake

Cayuga Lake (,,) is the longest of central New York's glacial Finger Lakes, and is the second largest in surface area (marginally smaller than Seneca Lake) and second largest in volume. It is just under long. Its average width is , and it is ...

and hosts the

Finger Lakes Institute

A finger is a limb of the body and a type of digit, an organ of manipulation and sensation found in the hands of most of the Tetrapods, so also with humans and other primates. Most land vertebrates have five fingers ( Pentadactyly). Chambers ...

, a non-profit institute focusing on education and ecological preservation for the Finger Lakes area.

On Seneca Lake one will find the ''William Scandling'', a Hobart and William Smith research vessel used to monitor lake conditions and in the conduct of student and faculty research.

The Colleges also own and operate

WEOS

WEOS is a college radio station licensed to Geneva, New York, broadcasting primarily on 89.5 FM across the Finger Lakes region of New York. It also broadcasts on a smaller relay transmitter on 90.3FM in Geneva (call sign W212BA). The station i ...

-FM and

WHWS-LP, public radio stations broadcasting throughout the Finger Lakes and worldwide, on the web.

Academics

Hobart and William Smith Colleges offer the degrees of

Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

,

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

, and

Master of Arts in Teaching

The Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) or Master of Science in Teaching (MST) degree is generally a pre-service degree that usually requires a minimum of 30 semester hours beyond the bachelor's degree. While the program often requires education c ...

. The colleges follow the semester calendar, have a student to faculty ratio of 10:1 and average class size of 16. Hobart and William Smith Colleges are accredited by the

Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools

The Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools (Middle States Association or MSA) was a voluntary, peer-based, non-profit association that performed peer evaluation and regional educational accreditation, accreditation of public and priva ...

and

The University of the State of New York

Curriculum

The curriculum was last reviewed and revised in the 2014–15 academic year. Voted on by the faculty, the curriculum adopted the animating principle: Explore. Collaborate. Act. The revisions also adopted a Writing Enriched Curriculum model, the implementation of capstone experiences across all programs and departments and enhanced the First Year Experience. Specifically, to graduate from Hobart and William Smith Colleges, students must:

*Pass 32 academic courses, including a First-Year Seminar

*Complete the requirements for an academic major, including a capstone course or experience, and an academic minor (or second major). Students cannot major and minor in the same subject.

*Complete a course of study, designed in consultation with a faculty adviser, which addresses each of the eight educational goals:

# Critical Thinking

# Communication

# Quantitative Reasoning

# Scientific Inquiry

# Artistic Process

# Social Inequalities

# Cultural Difference

# Ethical Judgment

First-Year Seminar

First-Year Seminars are discussion-centered, interdisciplinary and collaborative. The only required course at HWS, seminar classes are small – usually about 15 students. Through the First-Year Seminar students:

# Develop critical thinking and communication skills

# Understand the Colleges’ intellectual and ethical values

# Establish a strong network of relationships with peers and mentors

Seminar topics vary each year, as do the professors who teach them. Many First-Year Seminars are linked to a Learning Community. Students enrolled in a Learning Community take one or more courses together. They also live together on the same floor of a co-ed residence hall and attend some of the same lectures and field trips.

Global education

More than 60% of Hobart and William Smith students participate in off-campus study before they graduate. The Colleges maintain a robust menu of programs, 50+ sites on 6 continents, offering a wide array of options in different academic disciplines around the world. Admission to these programs is competitive.

In the 2020 edition of The Princeton Review's Best 385 Colleges, Hobart and William Smith Colleges study abroad program is ranked third on the “Most Popular Study Abroad” list, marking four years in a row that HWS has been a top-10 study abroad school (No. 7 in 2017 and No. 1 in the 2018 and 2019 editions).

President Joyce P. Jacobsen

On July 1, 2019,

Joyce P. Jacobsen

Joyce Penelope Jacobsen is a former President of Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Dr. Jacobsen was elected as the 29th President of Hobart College and the 18th President of William Smith College. Jacobsen is a scholar of economics, an award-winn ...

began serving as the 29th President of Hobart College and the 18th of William Smith College. She is the first woman to serve as president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

Rankings

In its 2020 edition, ''

U.S. News & World Report'' ranks Hobart and William Smith Colleges as tied for 72nd best liberal arts college in the U.S. and tied for 60th in "Best Undergraduate Teaching".

In 2019, ''

Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also re ...

'' rated it 190th overall in "America's Top Colleges," which ranked 650 national universities, liberal arts colleges and service academies.

Trias Writers-in-Residence

Founded in 2011 with a grant from alumnus

Peter Trias

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

, Hobart and William Smith Colleges established the Trias Writer-in-Residence, which brings renowned authors to campus for a year to mentor undergraduate creative writing students. Former writers in residence have included

Mary Ruefle

Mary Ruefle (born 1952) is an American poet, essayist, and professor. She has published many collections of poetry, the most recent of which, ''Dunce'' (Wave Books, 2019), was longlisted for the National Book Award in Poetry and was a finalist f ...

,

Mary Gaitskill

Mary Gaitskill (born November 11, 1954) is an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. Her work has appeared in ''The New Yorker'', ''Harper's Magazine'', ''Esquire'', ''The Best American Short Stories'' (1993, 2006, 2012, 2020), and ...

, Tom Piazza,

Chris Abani, and

John D'Agata

John D’Agata (born 1975) is an American essayist. He is the author or editor of six books of nonfiction, including ''The Next American Essay'' (2003), ''The Lost Origins of the Essay'' (2009) and ''The Making of the American Essay''—all part ...

.

Elizabeth Blackwell Award

In honor of

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman in America to receive the Doctor of Medicine degree, the Elizabeth Blackwell Award is given by Hobart and William Smith Colleges to a woman whose life exemplifies outstanding service to humanity. Its recipients have included

Chair of the Federal Reserve

The chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the Federal Reserve, and is the active executive officer of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The chair shall preside at the meetings of the Boa ...

Janet Yellen

Janet Louise Yellen (born August 13, 1946) is an American economist serving as the 78th United States secretary of the treasury since January 26, 2021. She previously served as the 15th chair of the Federal Reserve from 2014 to 2018. Yellen is t ...

(2015); the Most Rev.

Katharine Jefferts Schori

Katharine Jefferts Schori (born March 26, 1954) is the former Presiding Bishop and Primate of the Episcopal Church of the United States. Previously elected as the 9th Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, she was the first woman elected ...

(2013);

Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Eunice Mary Kennedy Shriver (July 10, 1921 – August 11, 2009) was an American philanthropist and a member of the Kennedy family. She was the founder of the Special Olympics, a sports organization for persons with physical and intellectual disa ...

(2011); first woman ordained a rabbi in the United States, Rabbi

Sally Priesand

Sally Jane Priesand (born June 27, 1946) is America's first female rabbi Semikha, ordained by a rabbinical seminary, and the second formally ordained female rabbi in Jewish history, after Regina Jonas. Priesand was ordained by the Hebrew Union Co ...

(2009);

Wangari Maathai

Wangarĩ Muta Maathai (; 1 April 1940 – 25 September 2011) was a Kenyan social, environmental and a political activist and the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. As a beneficiary of the Kennedy Airlift, she studied in the Un ...

(2008), first African woman to receive the

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

; the first woman to be ordained to the episcopate in the worldwide Anglican Communion,

Bishop Barbara Harris (2004);

Secretary of State Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 64th United States secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. A member of the Democratic ...

(2001); tennis great

Billie Jean King

Billie Jean King (née Moffitt; born November 22, 1943) is an American former world No. 1 tennis player. King won 39 major titles: 12 in singles, 16 in women's doubles, and 11 in mixed doubles. King was a member of the victorious United States ...

(1998);

Wilma Mankiller

Wilma Pearl Mankiller ( chr, ᎠᏥᎳᏍᎩ ᎠᏍᎦᏯᏗᎯ, Atsilasgi Asgayadihi; November 18, 1945April 6, 2010) was a Native American (Cherokee Nation) activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve a ...

(1996), first woman chief of the Cherokee Nation;

U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

Barbara Jordan

Barbara Charline Jordan (February 21, 1936 – January 17, 1996) was an American lawyer, educator, and politician. A Democrat, she was the first African American elected to the Texas Senate after Reconstruction and the first Southern African-A ...

(1993); U.S. Senator

Margaret Chase Smith

Margaret Madeline Smith (née Chase; December 14, 1897 – May 29, 1995) was an American politician. A member of the Republican Party, she served as a U.S. representative (1940–1949) and a U.S. senator (1949–1973) from Maine. She was the firs ...

(1991); former Surgeon General

Antonia Novello

Antonia Coello Novello, M.D., (born August 23, 1944) is a Puerto Rican physician and public health administrator. She was a vice admiral in the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps and served as 14th Surgeon General of the United States from ...

(1991); Supreme Court Justice

Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

(1985);

Fe del Mundo, the first Asian woman admitted to

Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is consi ...

(1966);

Miki Sawada, who started an orphanage for abandoned mixed-race children (1960); among many others.

President's Forum

Each semester, Hobart and William Smith sponsors a series of guest lectures. The most prominent has been the President's Forum, established in 2000 and led by former president

Mark Gearan. The forum has included The Hon.

Shireen Avis Fisher

Justice Shireen Avis Fisher is a justice of the Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone, having been appointed to the role in October 2013 following the ad hoc tribunal's dissolution that year and having previously served as an Appeals Judge on th ...

,

Nancy Zimpher

Nancy L. Zimpher (born October 29, 1946) is an American educator, state university leader, and former Chancellor of the State University of New York (SUNY). Prior to her service at SUNY, Zimpher was a dean and professor of education at Ohio Stat ...

,

Mary Matalin

Mary Joe Matalin (born August 19, 1953) is an American political consultant well known for her work with the Republican Party. She has served under President Ronald Reagan, was campaign director for George H. W. Bush, was an assistant to Presid ...

and

James Carville

Chester James Carville Jr. (born October 25, 1944) is an American political consultant, author, and occasional actor who has strategized for candidates for public office in the United States and in at least 23 nations abroad. A Democrat, he is an ...

,

Kathy Platoni,

Svante Myrick

Svante L. Myrick (born March 15, 1987) is an American politician who formerly served as the mayor of Ithaca, New York. He is a member of the Democratic Party.

Raised in the town of Earlville, New York, Myrick was elected to the Ithaca Common Coun ...

,

Cornel West

Cornel Ronald West (born June 2, 1953) is an American philosopher, political activist, social critic, actor, and public intellectual. The grandson of a Baptist minister, West focuses on the role of race, gender, and class in American society an ...

,

Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the Un ...

,

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

,

Eric Liu

Eric P. Liu (born 1968) is an American writer, former civil servant, and founder of Citizen University, a non-profit organization promoting civics education and awareness. Liu served as Deputy Assistant to President Clinton for Domestic Polic ...

, and

Alan Keyes

Alan Lee Keyes (born August 7, 1950) is an American politician, political activist, author, and perennial candidate who served as the Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs from 1985 to 1987. A member of the Repub ...

, among other prominent names.

Publications

''Seneca Review'', founded in 1970 by James Crenner and Ira Sadoff, is published twice yearly, spring and fall, by Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press. Distributed internationally, the magazine's emphasis is poetry, and the editors have a special interest in translations of contemporary poetry from around the world. Publisher of numerous laureates and award-winning poets, including

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. ,

Rita Dove

Rita Frances Dove (born August 28, 1952) is an American poet and essayist. From 1993 to 1995, she served as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. She is the first African American to have been appointed since the posit ...

,

Jorie Graham

Jorie Graham (; born May 9, 1950) is an American poet. The Poetry Foundation called Graham "one of the most celebrated poets of the American post-war generation." She replaced poet Seamus Heaney as Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at ...

,

Yusef Komunyakaa

Yusef Komunyakaa (born James William Brown; April 29, 1941) is an American poet who teaches at New York University and is a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. Komunyakaa is a recipient of the 1994 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, for ''Neo ...

,

Lisel Mueller

Lisel Mueller (born Elisabeth Neumann, February 8, 1924 – February 21, 2020) was a German-born American poet, translator and academic teacher. Her family fled the Nazi regime, and she arrived in the U.S. in 1939 at the age of 15. She worked as a ...

,

Wislawa Szymborska,

Charles Simic

Dušan Simić ( sr-cyr, Душан Симић, ; born May 9, 1938), known as Charles Simic, is a Serbian American poet and former co-poetry editor of the ''Paris Review''. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for ''The World Doesn't ...

,

W.S. Merwin

William Stanley Merwin (September 30, 1927 – March 15, 2019) was an American poet who wrote more than fifty books of poetry and prose, and produced many works in translation. During the 1960s anti-war movement, Merwin's unique craft was thema ...

, and

Eavan Boland

Eavan Aisling Boland (24 September 1944 – 27 April 2020) was an Irish poet, author, and professor. She was a professor at Stanford University, where she had taught from 1996. Her work deals with the Irish national identity, and the role of w ...

, ''Seneca Review'' also consistently publishes emerging writers. In 1997, ''Seneca Review'' began publishing the "lyric essay," creative nonfiction that borders on poetry, under the associate editorship of

John D'Agata

John D’Agata (born 1975) is an American essayist. He is the author or editor of six books of nonfiction, including ''The Next American Essay'' (2003), ''The Lost Origins of the Essay'' (2009) and ''The Making of the American Essay''—all part ...

.

''Echo and Pine'' is the annual student-produced college yearbook. Originally two separate publications, the ''Hobart Echo'' of Seneca, and the ''William Smith Pine'', the two merged in the 1960s to create one publication to serve both colleges.

''The Herald'' is the student-run school newspaper, founded in the late 19th century as the ''Hobart Herald''.

''The Pulteney St. Survey'' is the official magazine of Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

''martini'' is the alternative student publication at Hobart & William Smith Colleges featuring an oftentimes witty and critical look at music, politics and social issues on both the Colleges' campus and on the national level.

''Thel'' provides an outlet for HWS student artists and writers. The bi-annual, student-run publication features poetry, photography, visual art and short stories created by HWS students.

The ''Aleph'' is a journal that expresses global perspectives by conveying the insights of HWS and

Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

students who studied abroad in joint programs as well as international and exchange students from both campuses. The journal is sponsored by the Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College Partnership for Global Education.

Debate

The HWS Debate Team dates back over 100 years. Notable recent victories include the 2016 Cornell IV, the 2015 Brad Smith Debate Tournament @ University of Rochester, the 2012 US National Championships, and the 2012 and 2009 Northeastern Regional Championship. The team hosts the HWS IV (one of the largest tournaments in North America) each fall, and the HWS Round Robin (an international tournament of champions) each spring. Every year, an HWS debater is honored with the Nathan D. Lapham Prize in Public Speaking, which comes with a cash award of up to $1000 to the student. HWS is among the few liberal-arts colleges to offer numerous four-year debate scholarships.

Music

Hobart and William Smith has a number of ensemble groups, including:

Colleges Chorale, a mixed ensemble which performs a wide range of a cappella choral repertoire — music from the Middle Ages to the present. In addition to a formal concert at the end of each semester and the annual spring tour, the Colleges Chorale performs at various campus events throughout the year.

Cantori is a chamber vocal ensemble comprising members from the larger Colleges Chorale. Since the group's formation in 1993, the sixteen-member Cantori has sought to foster contemporary choral music through the Cantori Commissioning Project – the annual commissioning and performance of a new work by a deserving American composer.

Classical Guitar Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student guitarists.

Community Chorus - students, faculty and staff at the Colleges, and members from the surrounding community. The fifty-voice ensemble performs major works from the standard repertoire as well as lesser-known works deserving wider familiarity. Recent programs have included extended works by Franz Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Gabriel Fauré, Ottorino Respighi, Sir Edward Elgar, Aaron Copland, Benjamin Britten, and Randall Thompson.

Community Wind Ensemble - students, faculty and staff at the Colleges, and members from the surrounding community. This relatively new ensemble looks forward to exploring the rich and diverse repertoire composed for wind ensemble.

Jazz Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student jazzers. Arrangements are found to accommodate a variety of instrumental combinations.

Jazz Guitar Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student jazz guitarists.

Percussion Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student percussionists, although students with minimal experience are encouraged to audition.

String Ensemble - a student chamber group providing a performance opportunity for talented string players.

Hobartones - Hobart College's student-run all-male a cappella group.

Three Miles Lost - William Smith College's student-run all-female a cappella group

Perfect Third - HWS's student run, coed a cappella group.

Coordinate system

Founded as two separate colleges, Hobart for men in 1822 and William Smith for women in 1908, Hobart and William Smith Colleges preserve their own identities while benefiting from a shared campus, faculty, administration and curriculum. The Colleges welcome students of all gender identities.

The two colleges combined gradually. In 1922, the first joint commencement was held, though baccalaureate services remained separate until 1942. By then, coeducational classes had become the norm, and the curriculum centered on the idea of an across-the-board education, encouraging students and faculty to consider their studies from several points of view.

In 1943, during the administration of President John Milton Potter, William Smith College was elevated from its original status as a department of Hobart College to that of an independent college, on equal footing with Hobart.

Today, Hobart and William Smith students retain their own deans, athletic departments and student governments. Each college celebrates its history through a series of time-honored traditions beginning when each student matriculates and lasting through graduation. Maintaining their traditional gender separation - Hobart College for men and William Smith College for women - the Colleges celebrate their position as one of the few remaining coordinate systems in the nation.

Coordinate traditions

Matriculation exercises

Upon arriving to campus for orientation, students and their families are personally greeted by the president before signing their name in the matriculation book. On the eve of the first day of classes, new students are invited to attend matriculation ceremonies hosted by the Dean's Offices.

Academic excellence

The Hobart and William Smith Dean's Offices recognize the academic and social achievements of their students at celebratory events each spring semester.

* Benjamin Hale Dinner - Students and distinguished alumni come together to recognize the best of Hobart student achievements.

* Celebrating Excellence Dinner - The academic achievements of William Smith students are recognized and new members of the Laurel Honor Society are inducted.

* Moving Up Day - Students gather by class at the top of William Smith Hill and process down The Hill with the seniors carrying a laurel rope. The event culminates with the passing of the laurel from the seniors to the juniors and all students “Moving Up.” Academic awards are given, new members of the Hai Timiai Honor Society are inducted and the Dean reflects on the year.

Honoring the colleges' founders

In honor of John Henry Hobart and William Smith, the community gathers each year to mark the founding of Hobart College and William Smith College.

* Charter Day - The campus community commemorates the founding of Hobart College and the day on which a provisional charter from the State Regents of New York officially brought the college into being. New inductees are welcomed to the Hobart honor societies and a distinguished alumnus is invited to speak.

* Founder's Day - Students, alumnae, administrators and faculty members gather to celebrate the establishment of William Smith College and the achievements of its students. A notable William Smith alumna addresses the community and engages in a public dialogue.

Alumni/ae welcome

Hosted by the Alumni and Alumnae Associations, soon-to-be graduates are officially welcomed into the alum community during graduation weekend.

* Hobart Launch - Each member of the Hobart class is given an oar in celebration of his alma mater, its heritage and the promise of a reciprocal lifelong bond.

* William Smith Welcome Toast - The William Smith seniors are toasted by the alumnae, plant a class pine tree and each member receives a pine tree charm in honor of the college's nurseryman founder.

Athletics

Varsity sports

There are 23 varsity sports at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, with about 25% of students involved at the varsity level. Hobart sponsors 11 varsity programs (basketball, cross country, football, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, rowing, sailing, soccer, squash, tennis), while William Smith also sponsors 12 varsity programs (basketball, cross country, field hockey, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, rowing, sailing, soccer, squash, swimming & diving, tennis). Hobart and William Smith varsity teams have won 23 national championships and 104 conference championships, producing 665

All-Americans

The All-America designation is an annual honor bestowed upon an amateur sports person from the United States who is considered to be one of the best amateurs in their sport. Individuals receiving this distinction are typically added to an All-Am ...

and 43

Academic All-America

The Academic All-America program is a student-athlete recognition program. The program selects an honorary sports team composed of the most outstanding student-athletes of a specific season for positions in various sports—who in turn are giv ...

honorees.

In March 2017, Hobart and William Smith were named to the "100 Best Colleges for Sports Lovers" by

''Money'' and ''

Sports Illustrated

''Sports Illustrated'' (''SI'') is an American sports magazine first published in August 1954. Founded by Stuart Scheftel, it was the first magazine with circulation over one million to win the National Magazine Award for General Excellence twic ...

''.

;History

Originally known as the Hobart Deacons, Hobart's athletic teams became known as the "Statesmen" in 1936, following the football team's season opener against

Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educatio ...

. The morning after the game, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' referred to the team as "the statesmen from Geneva," and the name stuck. The nickname for William Smith's athletic teams comes from a contest held in 1982. Several names were submitted, but "

Heron

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychus ...

s" was selected because of the strong and graceful birds that lived at nearby Odell's Pond. These ominous birds frequently flew over the athletic fields as the teams were practicing.

;Affiliations

The colleges compete in

NCAA Division III

NCAA Division III (D-III) is a division of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in the United States. D-III consists of athletic programs at colleges and universities that choose not to offer athletic scholarships to their stu ...

, with the exception of men's

lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensively ...

, which competes in the

Division I Atlantic 10 Conference

The Atlantic 10 Conference (A-10) is a collegiate athletic conference whose schools compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association's (NCAA) Division I. The A-10's member schools are located in states mostly on the United States Eastern ...

(A-10). The colleges' main conference affiliation is with the

Liberty League

The Liberty League is an intercollegiate athletic conference affiliated with the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Division III. Member schools are top institutions that are all located in the state of New York.

History

It was founde ...

with the following exceptions: Hobart

ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice hock ...

competes in the

New England Hockey Conference

New England Hockey Conference (formerly the ECAC East) is a college athletic conference which operates in the northeastern United States. It participates in the NCAA's Division III as a hockey-only conference.

__TOC__

History

The New England Ho ...

; Hobart lacrosse competes in the A-10; and William Smith ice hockey competes in the

United Collegiate Hockey Conference

The United Collegiate Hockey Conference (UCHC) is a college athletic conference which operates in Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania in the eastern United States. It participates in NCAA Division III as a hockey-only conference.

The confer ...

..

;Facilities

Hobart and William Smith recently finished construction on the Caird Center for Sports and Recreation, which is now home to most of its athletics teams.

;Football

Offensive linesman

Ali Marpet, drafted in the second round, 61st overall, of the

2015 NFL draft

The 2015 NFL Draft was the 80th annual meeting of National Football League (NFL) franchises to select newly eligible football players. It took place in Chicago at the Auditorium Theatre and in Grant Park, from April 30 to May 2. The previous ...

, is the highest-drafted pick in the history of

Division III

In sport, the Third Division, also called Division 3, Division Three, or Division III, is often the third-highest division of a league, and will often have promotion and relegation with divisions above and below.

Association football

*Belgian Thir ...

football.

He was three-time All-

Liberty League

The Liberty League is an intercollegiate athletic conference affiliated with the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Division III. Member schools are top institutions that are all located in the state of New York.

History

It was founde ...

first team (2012, 2013, 2014), and 2014 Liberty League Co-Offensive Player of the Year—the first offensive lineman in league history to be so honored.

;Field hockey

The William Smith field hockey team has captured three national championships, ascending to the top of Division III in 1992, 1997 and 2000.

;Lacrosse

The Statesmen lacrosse team has compiled fifteen national championships (1 USILA, 2 NCAA Division II, and 13 NCAA Division III).

;Sailing

The lone coed team, the HWS

sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, windsurfer, or kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (land yacht) over a chosen cour ...

team is a member of the

Middle Atlantic Intercollegiate Sailing Association

Middle Atlantic Intercollegiate Sailing Association (MAISA) is one of the seven conferences affiliated with the Inter-Collegiate Sailing Association that schedule and administer regattas within their established geographic regions.

MAISA organiz ...

. In 2005, the Colleges won the

Inter-Collegiate Sailing Association

The Inter-Collegiate Sailing Association (ICSA) is a volunteer organization that serves as the governing authority for all sailing competition at colleges and universities throughout the United States and in some parts of Canada.

History

The fir ...

Team Race National Championship and the ICSA Coed Dinghy National Championship.

;Soccer

The William Smith soccer team was the first Heron squad to capture a national championship, winning the 1988

title bout with a 1–0 victory over

University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Insti ...

.

;Crew

The Hobart Crew team has also found success, earning gold medals at the Head of The Charles Regatta, the ECAC National Invitational Regatta (most recently a gold in the 2nd varsity 8+ over the "Hometown Boys" of WPI in 2015), and the IRA National Championships. While the Hobart Crew team has won gold in every event they have entered since the inception of rowing as a Liberty League Sport, they failed to win the team championships only once (2004.) The eventual champions, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, were known for having a large team and only able to defeat the Statesmen by securing a win in the 2nd Varsity 8+ – the only event that Hobart did not have an entry. However, over the past few seasons Hobart has fielded one of the most dominant 2nd Varsity 8's in school history. The Crew Team took part in the Henley Royal Regatta in Henley, England in the summer of 2011, as well as the summer of 2015.

Rivalries

Hobart's archrival in football is

Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

. Other team rivalries include

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute () (RPI) is a private research university in Troy, New York, with an additional campus in Hartford, Connecticut. A third campus in Groton, Connecticut closed in 2018. RPI was established in 1824 by Stephen Van ...

(football, basketball);

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester (U of R, UR, or U of Rochester) is a private research university in Rochester, New York. The university grants undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctoral and professional degrees.

The University of Roc ...

(football);

Elmira College

Elmira College is a private college in Elmira, New York. Founded as a college for women in 1855, it is the oldest existing college granting degrees to women that were the equivalent of those given to men. Elmira College became coeducational in a ...

and

Manhattanville College

Manhattanville College is a private university in Purchase, New York. Founded in 1841 at 412 Houston Street in lower Manhattan, it was initially known as Academy of the Sacred Heart, then after 1847 as Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart ...

(hockey);

Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

(

one of the oldest in lacrosse) and

St. John Fisher University,

Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

and

Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

(lacrosse); and

University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

(crew). William Smith has rivalries with

St. Lawrence University (lacrosse, basketball, field hockey),

Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

(soccer, field hockey, basketball, lacrosse),

Hamilton College