Seminole Indian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in

After acquisition by the U.S. of Florida in 1821, many American slaves and Black Seminoles frequently escaped from

After acquisition by the U.S. of Florida in 1821, many American slaves and Black Seminoles frequently escaped from

, ''Network to Freedom,'' National Park Service, 2010, accessed 10 April 2013 They developed a village known as Red Bays on Andros. Federal construction and staffing of the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1825 reduced the number of slave escapes from this site. the United States has worked with the Bahamas to designated both Cape Florida and Red Bays as sites on the National

During the Seminole Wars, the Seminole people began to divide among themselves due to the conflict and differences in ideology. The Seminole population had also been growing significantly, though it was diminished by the wars. With the division of the Seminole population between Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Florida, they still maintained some common traditions, such as powwow trails and ceremonies. In general, the cultures grew apart in their markedly different circumstances, and had little contact for a century.

The

During the Seminole Wars, the Seminole people began to divide among themselves due to the conflict and differences in ideology. The Seminole population had also been growing significantly, though it was diminished by the wars. With the division of the Seminole population between Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Florida, they still maintained some common traditions, such as powwow trails and ceremonies. In general, the cultures grew apart in their markedly different circumstances, and had little contact for a century.

The

''LA Times''/''Washington Post'' News Service, printed in ''Sarasota Herald-Tribune,'' 20 October 1978, accessed 13 April 2013 After combining their claims, the Commission awarded the Seminole a total of $16 million in April 1976. It had established that, at the time of the 1823

The remaining few hundred Seminoles survived in the Florida swamplands, avoiding removal. They lived in the Everglades, to isolate themselves from European-Americans. Seminoles continued their distinctive life, such as "clan-based matrilocal residence in scattered thatched-roof chickee camps." Today, the Florida Seminole proudly note the fact that their ancestors were never conquered.

In the 20th century before World War II, the Seminole in Florida divided into two groups; those who were more traditional and those willing to adapt to the reservations. Those who accepted reservation lands and made adaptations achieved federal recognition in 1957 as the

The remaining few hundred Seminoles survived in the Florida swamplands, avoiding removal. They lived in the Everglades, to isolate themselves from European-Americans. Seminoles continued their distinctive life, such as "clan-based matrilocal residence in scattered thatched-roof chickee camps." Today, the Florida Seminole proudly note the fact that their ancestors were never conquered.

In the 20th century before World War II, the Seminole in Florida divided into two groups; those who were more traditional and those willing to adapt to the reservations. Those who accepted reservation lands and made adaptations achieved federal recognition in 1957 as the

The Seminole worked hard to adapt, but they were highly affected by the rapidly changing American environment. Natural disasters magnified changes from the governmental drainage project of the Everglades. Residential, agricultural and business development changed the "natural, social, political, and economic environment" of the Seminole. In the 1930s, the Seminole slowly began to move onto federally designated reservation lands within the region. The US government had purchased lands and put them in trust for Seminole use. Initially, few Seminoles had any interest in moving to the reservation land or in establishing more formal relations with the government. Some feared that if they moved onto reservations, they would be forced to move to Oklahoma. Others accepted the move in hopes of stability, jobs promised by the Indian New Deal, or as new

The Seminole worked hard to adapt, but they were highly affected by the rapidly changing American environment. Natural disasters magnified changes from the governmental drainage project of the Everglades. Residential, agricultural and business development changed the "natural, social, political, and economic environment" of the Seminole. In the 1930s, the Seminole slowly began to move onto federally designated reservation lands within the region. The US government had purchased lands and put them in trust for Seminole use. Initially, few Seminoles had any interest in moving to the reservation land or in establishing more formal relations with the government. Some feared that if they moved onto reservations, they would be forced to move to Oklahoma. Others accepted the move in hopes of stability, jobs promised by the Indian New Deal, or as new  Beginning in the 1940s, more Seminoles began to move to the reservations. A major catalyst for this was the conversion of many Seminole to Christianity, following missionary effort spearheaded by the Creek

Beginning in the 1940s, more Seminoles began to move to the reservations. A major catalyst for this was the conversion of many Seminole to Christianity, following missionary effort spearheaded by the Creek

In the early 20th century, Florida had a population boom after the Flagler

In the early 20th century, Florida had a population boom after the Flagler

LINK TO PDF

* Hawkins, Philip Colin. "The Textual Archaeology of Seminole Colonization." ''Florida Anthropologist'' 64 (June 2011), 107–113. *Mahon, John K.; Brent R. Weisman (1996). "Florida's Seminole and Miccosukee Peoples". In Gannon, Michael (Ed.). ''The New History of Florida'', pp. 183–206. University Press of Florida. .

*Twyman, Bruce Edward. '' The Black Seminole Legacy and North American Politics, 1693-1845'' (Howard University Press, 1999). * West, Patsy. ''The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wrestling to Ecotourism'' (1998)

Seminole Nation Historical siteSeminole Nation of Oklahoma official website

Seminole Tribe of Florida official site

Resources for Hitchiti and Mikasuki

William and Mary College

Seminole history

Florida Department of State

John Horse and the Black Seminoles, First Black Rebels to Beat American SlaveryClay MacCauley, ''The Seminole Indians of Florida''

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

, the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

, and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

, as well as independent groups. The Seminole people emerged in a process of ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

from various Native American groups who settled in Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

beginning in the early 1700s, most significantly northern Muscogee Creeks

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

.

The word "Seminole" is derived from the Muscogee word ''simanĂł-li''. This may have been adapted from the Spanish word ''cimarrĂłn'', meaning "runaway" or "wild one". Seminole culture is largely derived from that of the Creek; the most important ceremony is the Green Corn Dance

The Green Corn Ceremony (Busk) is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest. Busk is a term given to the ceremony by white traders, the word being a corruption of t ...

; other notable traditions include use of the black drink

Black drink is a name for several kinds of ritual beverages brewed by Native Americans in the Southeastern United States. Traditional ceremonial people of the Yuchi, Caddo, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee and some other Indigenous peop ...

and ritual tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

. As the Seminole adapted to Florida environs, they developed local traditions, such as the construction of open-air, thatched-roof houses known as ''chickee

Chikee or Chickee ("house" in the Creek and Mikasuki languages spoken by the Seminoles and Miccosukees) is a shelter supported by posts, with a raised floor, a thatched roof and open sides. Chickees are also known as chickee huts, stilt houses, ...

s''. Historically the Seminole spoke Mikasuki

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

and Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

, both Muskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

.

Florida had been the home of several indigenous cultures prior the arrival of European explorers in the early 1500s. However, the introduction of Eurasian infectious diseases, along with conflict with Spanish and English colonists, led to a drastic decline of Florida's original native population. By the early 1700s, much of ''La Florida'' was uninhabited apart from towns at St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

and Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. A stream of mainly Muscogee Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlandsethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

. They developed a thriving trade network by the time of the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and second Spanish periods (roughly 1767–1821). The tribe expanded considerably during this time, and was further supplemented from the late 18th century by escaped slaves from Southern plantations who settled near and paid tribute to Seminole towns. The latter became known as Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

, although they kept many facets of their own Gullah

The Gullah () are an African Americans, African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the South Carolina Lowcountry, Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain ...

culture.Mahon, pp. 190–191.

After the United States achieved independence, settlers in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

increased pressure on Seminole lands, and skirmishes near the border led to the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

(1816–19). The United States purchased Florida from Spain by the Adams-Onis Treaty (1819) and took possession in 1821. The Seminole were moved out of their rich farmland in northern Florida and confined to a large reservation in the interior of the Florida peninsula by the Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in t ...

(1823). Passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

(1830) led to the Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

(1832), which called for the relocation of all Seminole to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

(now Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

). Some resisted, leading to the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

, the bloodiest war against Native Americans in United States history. By 1842, however, most Seminoles and Black Seminoles, facing starvation, were removed to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Perhaps fewer than 200 Seminoles remained in Florida after the Third Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

(1855–1858), having taken refuge in the Everglades, from where they never surrendered to the US. They fostered a resurgence in traditional customs and a culture of staunch independence.Mahon, pp. 201–202

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, some Seminole bands in Indian Territory allied with the Confederacy, while others were divided between supporting the North and South. After the war, the United States government declared void all prior treaties with the Seminoles of Indian Country because of the "disloyalty" of some in allying with the Confederacy. They required new peace treaties, establishing such conditions as reducing the power of tribal councils, providing freedom or tribal membership for Black Seminoles (at the same time that enslaved African Americans were being emancipated in the South), and forced concessions of tribal land for railroads and other development.

The Confederacy had offered aid to the many fewer Seminoles of Florida, to dissuade them from siding with Union forces operating in the southern part of the state. Although supplies were often not delivered as promised due to wartime shortages, the Seminoles had no desire to enter another war and remained neutral.

After Removal, the Seminoles in Oklahoma and Florida had little official contact until well into the 20th century. They developed along similar lines as the groups strove to maintain their culture while struggling economically. Most Seminoles in Indian Territory lived on tribal lands centered in what is now Seminole County of the state of Oklahoma. The implementation of the Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exec ...

in the late 1890s parceled out tribal lands in preparation for the admission of Oklahoma as a state, reducing most Seminoles to subsistence farming

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow food crops to meet the needs of themselves and their families on smallholdings. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements, with little or no su ...

on small individual homesteads. While some tribe members left the territory to seek better opportunities, most remained. Today, residents of the reservation are enrolled in the federally recognized Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

, while others belong to unorganized groups. The Florida Seminole re-established limited relations with the U.S. government in the early 1900s and were officially granted of reservation land in south Florida in 1930. Members gradually moved to the land, and they reorganized their government and received federal recognition as the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

in 1957. The more traditional people living near the Tamiami Trail

The Tamiami Trail () is the southernmost of U.S. Highway 41 (US 41) from State Road 60 (SR 60) in Tampa to US 1 in Miami. A portion of the road also has the hidden designation of State Road 90 (SR 90).

The north†...

received federal recognition as the Miccosukee

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

Tribe in 1962.Mahon, pp. 203–204.

Old crafts and traditions were revived in both Florida and Oklahoma in the mid-20th century as the Seminole began seeking tourism dollars from Americans traveling along the new interstate highway system

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. Th ...

. In the 1970s, Seminole tribes began to run small bingo

Bingo or B-I-N-G-O may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Gaming

* Bingo, a game using a printed card of numbers

** Bingo (British version), a game using a printed card of 15 numbers on three lines; most commonly played in the UK and Ireland

** Bi ...

games on their reservations to raise revenue. They won court challenges to initiate Indian gaming Indian gaming may refer to:

*Native American gaming, gambling activities on indigenous tribal lands in the United States

*Gambling in India, gambling activities in the country of India

*Video games in India

Video gaming in India is an emerging m ...

on their sovereign land, which many U.S. tribes have adopted to generate revenues for welfare, education, and development.

Given the numerous tourists to the state, the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

has been particularly successful with gambling establishments since the late 20th century. It purchased the Hard Rock Café

Hard Rock Cafe, Inc. is a British-based multinational chain of theme restaurants, memorabilia shops, casinos and museums founded in 1971 by Isaac Tigrett and Peter Morton in London. In 1979, the cafe began covering its walls with rock and rol ...

in 2007 and has rebranded or opened several casino

A casino is a facility for certain types of gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shopping, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos are also known for hosting live entertai ...

s and gaming resorts under that name. These include two large resorts on its Tampa

Tampa () is a city on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The city's borders include the north shore of Tampa Bay and the east shore of Old Tampa Bay. Tampa is the largest city in the Tampa Bay area and the seat of Hillsborough County ...

and Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

reservations that together cost over a billion dollars to construct.

Etymology

The word "Seminole" is almost certainly derived from the Creek word ''simanĂł-li'', which has been variously translated as "frontiersman", "outcast", "runaway", "separatist", and similar words. The Creek word may be derived from the Spanish word ''cimarrĂłn'', meaning "runaway" or "wild one", historically used for certain Native American groups in Florida. The people who constituted the nucleus of this Florida group either chose to leave their tribe or were banished. At one time, the terms "renegade" and "outcast" were used to describe this status, but the terms have fallen into disuse due to their negative connotations. The Seminole identify as ''yat'siminoli'' or "free people" because for centuries their ancestors had successfully resisted efforts to subdue or convert them toRoman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. They signed several treaties with the U.S. government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

, including the Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in t ...

and the Treaty of Paynes Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

.

History

Origins

Native American refugees from northern wars, such as theYuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...

and Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

after the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

in South Carolina, migrated into Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

in the early 18th century. More arrived in the second half of the 18th century, as the Lower Creeks, part of the Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsProvince of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

. They spoke primarily Hitchiti

The Hitchiti ( ) were a historic indigenous tribe in the Southeast United States. They formerly resided chiefly in a town of the same name on the east bank of the Chattahoochee River, four miles below Chiaha, in western present-day Georgia. The n ...

, of which Mikasuki

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

is a dialect, which is the primary traditional language spoken today by the Miccosukee

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

in Florida. Also fleeing to Florida were African Americans who had escaped from slavery in the Southern colonies.

The new arrivals moved into virtually uninhabited lands that had once been peopled by several cultures indigenous to Florida, such as the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,Bobby ...

, Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The var ...

, Calusa

The Calusa ( ) were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

At the time of ...

, and others. The native population had been devastated by infectious diseases brought by Spanish explorers in the 1500s and later colonization by European settlers. Later, raids by Carolina

Carolina may refer to:

Geography

* The Carolinas, the U.S. states of North and South Carolina

** North Carolina, a U.S. state

** South Carolina, a U.S. state

* Province of Carolina, a British province until 1712

* Carolina, Alabama, a town in ...

and Native American slavers destroyed the string of Spanish missions across northern Florida, and most of the survivors left for Cuba when the Spanish withdrew after ceding Florida to the British in 1763, following the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

.

As they established themselves in northern and peninsular Florida throughout the 1700s, the various new arrivals intermingled with each other and with the few remaining indigenous people. In a process of ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

, they constructed a new culture which they called "Seminole", a derivative of the ''Mvskoke (a Creek language

The Muscogee language (Muskogee, ''Mvskoke'' in Muscogee), also known as Creek, is a Muskogean language spoken by Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole people, primarily in the US states of Oklahoma and Florida. Along with Mikasuki, when it is spoken by ...

) word ''simano-li'', an adaptation of the Spanish ''cimarrĂłn'' which means "wild" (in their case, "wild men"), or "runaway" en The Seminole were a heterogeneous tribe made up of mostly Lower Creeks from Georgia, who by the time of the Creek Wars

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

(1812–1813) numbered about 4,000 in Florida. At that time, numerous refugees of the Red Sticks

Red Sticks (also Redsticks, Batons Rouges, or Red Clubs), the name deriving from the red-painted war clubs of some Native American Creeks—refers to an early 19th-century traditionalist faction of these people in the American Southeast. Made u ...

migrated south, adding about 2,000 people to the population. They were Creek-speaking Muscogee, and were the ancestors of most of the later Creek-speaking Seminole. In addition, a few hundred escaped African-American slaves (known as the Black Seminole

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

) had settled near the Seminole towns and, to a lesser extent, Native Americans from other tribes, and some white Americans. The unified Seminole spoke two languages: Creek and Mikasuki (mutually intelligible with its dialect Hitchiti

The Hitchiti ( ) were a historic indigenous tribe in the Southeast United States. They formerly resided chiefly in a town of the same name on the east bank of the Chattahoochee River, four miles below Chiaha, in western present-day Georgia. The n ...

), two among the Muskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

family. Creek became the dominant language for political and social discourse, so Mikasuki speakers learned it if participating in high-level negotiations. (The Muskogean language group includes Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

and Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, associated with two other major Southeastern tribes.)

During the colonial years, the Seminole were on relatively good terms with both the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

and the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

. In 1784, after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Britain came to a settlement with Spain and transferred East and West Florida to it. The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquĂa Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquĂa CatĂłlica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

's decline enabled the Seminole to settle more deeply into Florida. They were led by a dynasty of chiefs of the Alachua chiefdom, founded in eastern Florida in the 18th century by Cowkeeper. Beginning in 1825, Micanopy

Micanopy (c. 1780 – December 1848 or January 1849), also known as Micco-Nuppe, Michenopah, Miccanopa, and Mico-an-opa, and Sint-chakkee ("pond frequenter", as he was known prior to being selected as chief), was the leading chief of the Sem ...

was the principal chief of the unified Seminole, until his death in 1849, after Removal to Indian Territory.Sattler (2004), p. 461 This chiefly dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

lasted past Removal, when the US forced the majority of Seminole to move from Florida to the Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

(modern Oklahoma) after the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

. Micanopy's sister's son, John Jumper John Jumper may refer to:

* John Jumper (Seminole chief), principal chief of the Seminole Nation

* John M. Jumper, AI researcher

* John P. Jumper

John Phillip Jumper (born February 4, 1945) is a retired United States Air Force general, who serv ...

, succeeded him in 1849 and, after his death in 1853, his brother Jim Jumper became principal chief. He was in power through the American Civil War, after which the US government began to interfere with tribal government, supporting its own candidate for chief.

Seminole Wars

After raids by Anglo-American colonists on Seminole settlements in the mid-18th century, the Seminole retaliated by raiding the Southern Colonies (primarilyGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

), purportedly at the behest of the Spanish. The Seminole also maintained a tradition of accepting escaped slaves from Southern plantations, infuriating planters

Planters Nut & Chocolate Company is an American snack food company now owned by Hormel Foods. Planters is best known for its processed nuts and for the Mr. Peanut icon that symbolizes them. Mr. Peanut was created by grade schooler Antonio Gentil ...

in the American South by providing a route for their slaves to escape bondage.

After the United States achieved independence, the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

and local militia groups made increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish Florida to recapture escaped slaves living among the Seminole. American general Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole became known as the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

. Though Spain decried the incursions into its territory, the United States effectively controlled the Florida panhandle after the war.

In 1819 the United States and Spain signed the Adams-OnĂs Treaty, which took effect in 1821. According to its terms, the United States acquired Florida and, in exchange, renounced all claims to Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. The president appointed Andrew Jackson as military governor of Florida. As European-American colonization increased after the treaty, colonists pressured the Federal government to remove Natives from Florida. Slaveholders resented that tribes harbored runaway Black slaves, and more colonists wanted access to desirable lands held by Native Americans. Georgian slaveholders wanted the "maroons" and fugitive slaves living among the Seminoles, known today as Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

, returned to slavery.

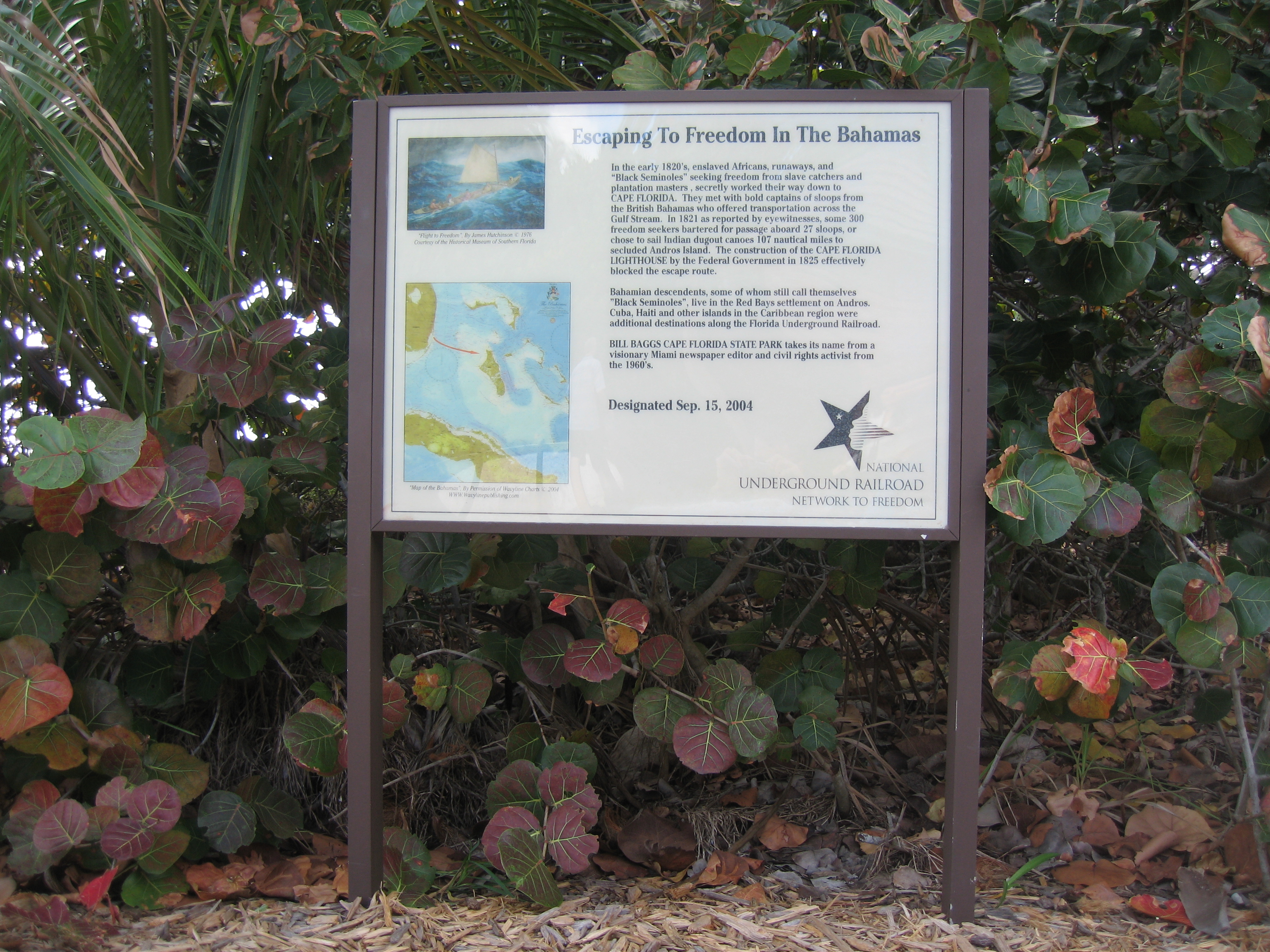

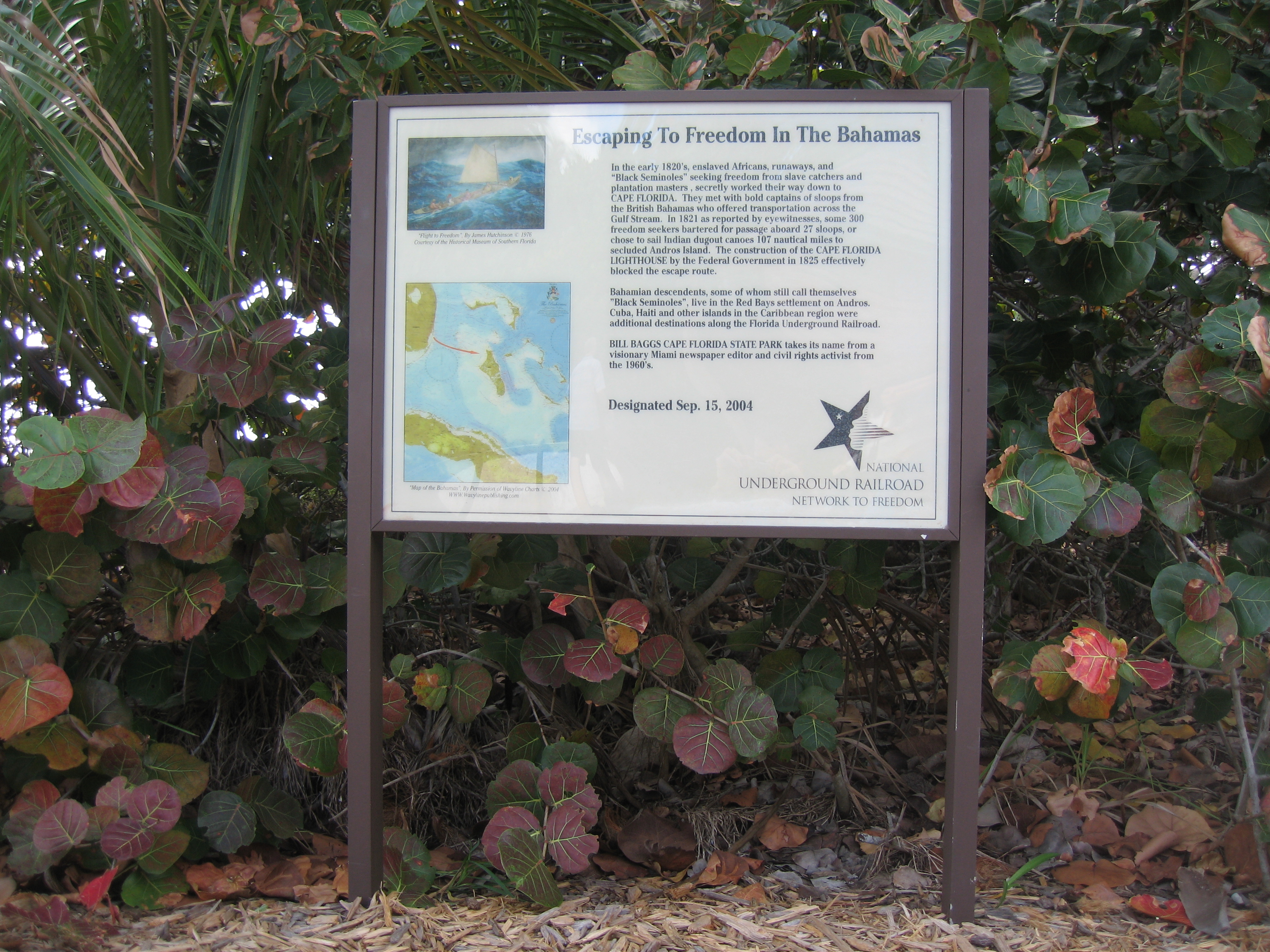

After acquisition by the U.S. of Florida in 1821, many American slaves and Black Seminoles frequently escaped from

After acquisition by the U.S. of Florida in 1821, many American slaves and Black Seminoles frequently escaped from Cape Florida

Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Recreation Area occupies approximately the southern third of the island of Key Biscayne, at coordinates . This park includes the Cape Florida Light, the oldest standing structure in Greater Miami. In 2005, it was ra ...

to the British colony of the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, settling mostly on Andros Island

Andros Island is an archipelago within the Bahamas, the largest of the Bahamian Islands. Politically considered a single island, Andros in total has an area greater than all the other 700 Bahamian islands combined. The land area of Andros consis ...

. Contemporary accounts noted a group of 120 migrating in 1821, and a much larger group of 300 enslaved African-Americans escaping in 1823. The latter were picked up by Bahamians in 27 sloops and also by travelers in canoes."Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park", ''Network to Freedom,'' National Park Service, 2010, accessed 10 April 2013 They developed a village known as Red Bays on Andros. Federal construction and staffing of the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1825 reduced the number of slave escapes from this site. the United States has worked with the Bahamas to designated both Cape Florida and Red Bays as sites on the National

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

Network to Freedom Trail.

After the independent United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821, white settlers increased political and governmental pressure on the Seminole to move and give up their lands. "The Seminoles were victims of a system that often blatantly favored whites".

Under colonists' pressure, the US government made the 1823 Treaty of Camp Moultrie with the Seminole, seizing 24 million acres in northern Florida. They offered the Seminole a much smaller reservation in the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical climate, tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orland ...

, of about . They and the Black Seminoles moved into central and southern Florida.

In 1832, the United States government signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

with a few of the Seminole chiefs. They promised lands west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

if the chiefs agreed to leave Florida voluntarily with their people. The Seminoles who remained prepared for war. White colonists continued to press for their removal.

In 1835, the U.S. Army arrived to enforce the treaty. The Seminole leader Osceola

Osceola (1804 – January 30, 1838, Asi-yahola in Muscogee language, Creek), named Billy Powell at birth in Alabama, became an influential leader of the Seminole people in Florida. His mother was Muscogee, and his great-grandfather was a S ...

led the vastly outnumbered resistance during the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

. Drawing on a population of about 4,000 Seminole and 800 allied Black Seminoles, he mustered at most 1,400 warriors (President Andrew Jackson estimated they had only 900). They countered combined U.S. Army and militia forces that ranged from 6,000 troops at the outset to 9,000 at the peak of deployment in 1837. To survive, the Seminole allies employed guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

with devastating effect against U.S. forces, as they knew how to move within the Everglades and use this area for their protection. Osceola was arrested (in a breach of honor) when he came under a flag of truce

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

to negotiations with the US in 1837. He died in jail less than a year later. He was decapitated, his body buried without his head.

Other war chiefs, such as Halleck Tustenuggee

Halleck Tustenuggee (also spelled Halek Tustenuggee and Hallock Tustenuggee) (c. 1807 – ?) was a 19th-century Seminole war chief. He fought against the United States government in the Second Seminole War and for the government in the American Civ ...

and John Jumper, and the Black Seminoles Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

and John Horse

John Horse (c. 1812–1882), also known as Juan Caballo, Juan Cavallo, John Cowaya (with spelling variations) and Gopher John, was of mixed ancestry (African and Seminole Indian) who fought alongside the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in Flo ...

, continued the Seminole resistance against the army. After a full decade of fighting, the war ended in 1842. Scholars estimate the U.S. government spent about $40,000,000 on the war, at the time a huge sum. An estimated 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were forcibly exiled to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi, where they were settled on the Creek reservation. After later skirmishes in the Third Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

(1855 -1858), perhaps 200 survivors retreated deep into the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical climate, tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orland ...

to land that was not desired by settlers. They were finally left alone and they never surrendered.

Several treaties seem to bear the mark of representatives of the Seminole tribe, including the Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in t ...

and the Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

. The Florida Seminole say they are the only tribe in America never to have signed a peace treaty with the U.S. government.

Post Seminole Wars and the 20th Century

The remaining Seminole in Florida adapted to their wetlands environment, while keeping many traditional customs and building a culture of staunch independence. During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Confederate government of Florida offered aid to keep the Seminole from fighting on the side of the Union. The Florida House of Representatives established a Committee on Indian Affairs in 1862 but, aside from appointing a representative to negotiate with the Seminole tribe, failed to follow its promises of aid. The lack of aid, along with the growing number of Federal troops and pro-unionists in the state, led the Seminole to remain officially neutral throughout the war. In July 1864, Secretary of War James A. Seddon

James Alexander Seddon (July 13, 1815 – August 19, 1880) was an American lawyer and politician who served two terms as a Representative in the U.S. Congress, as a member of the Democratic Party. He was appointed Confederate States Secretar ...

received word that a man named A. McBride had raised a company of sixty-five Seminole who had volunteered to fight for the Confederacy. McBride claimed to have an understanding of Florida because of the time he had spent there fighting during the Seminole wars. While McBride never put such a company in the field, this letter shows how the Confederacy attempted to use Seminole warriors against the Union.

The 1868 Florida Constitution, developed by the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

legislature, gave the Seminole one seat in the house and one seat in the senate of the state legislature. The Seminole never filled the positions. After white Democrats regained control over the legislature, they removed this provision from the post-Reconstruction constitution they ratified in 1885. In the early 20th century, the Florida Seminole re-established limited relations with the U.S. government. The Seminole maintained a thriving trade business with white merchants during this period, selling alligator hides, bird plumes, and other items sourced from the Everglades. Then, in 1906, Governor N.B. Broward began an effort to drain the Everglades in attempt to convert the wetlands into farmland. The plan to drain the Everglades, new federal and state laws ending the plume trade, and the start of World War I (which put a halt to international fashion trade), all contributed to a major decline in the demand for Seminole goods.

In 1930 they received of reservation lands. Few Seminole moved to these reservations until the 1940s. They reorganized their government and received federal recognition in 1957 as the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

. During this process, the more traditional people near the Tamiami Trail

The Tamiami Trail () is the southernmost of U.S. Highway 41 (US 41) from State Road 60 (SR 60) in Tampa to US 1 in Miami. A portion of the road also has the hidden designation of State Road 90 (SR 90).

The north†...

defined themselves as independent. They received federal recognition as the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians in Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

in 1962.

In the 1950s, the Oklahoma and Florida Seminole tribes filed land claim suits, claiming they had not received adequate compensation for their lands. Their suits were combined in the government's settlement of 1976. The Seminole tribes and Traditionals took until 1990 to negotiate an agreement as to division of the settlement, a judgment trust against which members can draw for education and other benefits. The Florida Seminole founded a high-stakes bingo game on their reservation in the late 1970s, winning court challenges to initiate Indian Gaming Indian gaming may refer to:

*Native American gaming, gambling activities on indigenous tribal lands in the United States

*Gambling in India, gambling activities in the country of India

*Video games in India

Video gaming in India is an emerging m ...

, which many tribes have adopted to generate revenues for welfare, education and development.

Political and social organization

The Seminole were organized around ''itálwa'', the basis of their social, political and ritual systems, and roughly equivalent to towns or bands in English. They had amatrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

kinship system, in which children are considered born into their mother's family and clan, and property and hereditary roles pass through the material line. Males held the leading political and social positions. Each ''itálwa'' had civil, military and religious leaders; they were self-governing throughout the nineteenth century, but would cooperate for mutual defense. The ''itálwa'' continued to be the basis of Seminole society in Oklahoma into the 21st century.

Languages

Historically, the various groups of Seminole spoke two mutually unintelligibleMuskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

: Mikasuki

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

(and its dialect, Hitchiti) and Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsMiccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

. The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

is working to revive the use of Creek among its people, as it had been the dominant language of politics and social discourse.

Muscogee is spoken by some Oklahoma Seminole and about 200 older Florida Seminole (the youngest native speaker was born in 1960). Today English is the predominant language among both Oklahoma and Florida Seminole, particularly the younger generations. Most Mikasuki speakers are bilingual.

Ethnobotany

Ethnobotany is the study of a region's plants and their practical uses through the traditional knowledge of a local culture and people. An ethnobotanist thus strives to document the local customs involving the practical uses of local flora for m ...

The Seminole use the spines of Cirsium horridulum

''Cirsium horridulum'', called bristly thistle, horrid thistle, yellow thistle or bull thistle, is a North American species of plants in the tribe Cardueae within the family Asteraceae. It is an annual or biennial. The species is native to the ...

(also called bristly thistle) to make blowgun darts.

Music

Contemporary

During the Seminole Wars, the Seminole people began to divide among themselves due to the conflict and differences in ideology. The Seminole population had also been growing significantly, though it was diminished by the wars. With the division of the Seminole population between Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Florida, they still maintained some common traditions, such as powwow trails and ceremonies. In general, the cultures grew apart in their markedly different circumstances, and had little contact for a century.

The

During the Seminole Wars, the Seminole people began to divide among themselves due to the conflict and differences in ideology. The Seminole population had also been growing significantly, though it was diminished by the wars. With the division of the Seminole population between Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Florida, they still maintained some common traditions, such as powwow trails and ceremonies. In general, the cultures grew apart in their markedly different circumstances, and had little contact for a century.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

and Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

, described below, are federally recognized, independent nations that operate in their own spheres.Cattelino, p. 41.

Religion

Seminole tribes generally follow Christianity, bothProtestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. They also observe their traditional Native religion, which is expressed through the stomp dance

The stomp dance is performed by various Eastern Woodland tribes and Native American communities in the United States, including the Muscogee, Yuchi, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Delaware, Miami, Caddo, Tuscarora, Ottawa, Quapaw, Peoria, Shaw ...

and the Green Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony (Busk) is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest. Busk is a term given to the ceremony by white traders, the word being a corruption of t ...

held at their ceremonial grounds. Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

have practiced Green Corn rituals for centuries. Contemporary southeastern Native American tribes, such as the Seminole and Muscogee Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsBrighton Seminole Indian Reservation

Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, located in northeast Glades County near the northwest shore of Lake Okeechobee. It is one of six reservations held in trust by the federal governmen ...

in Florida, viewed organized Christianity as a threat to their traditions.

By the 1980s, Seminole communities were even more concerned about loss of language and tradition. Many tribal members began to revive the observance of traditional Green Corn Dance ceremonies, and some shifted away from Christian observance. By 2000 religious tension between Green Corn Dance attendees and Christians (particularly Baptists) decreased. Some Seminole families participate in both religions; these practitioners have developed a syncretic Christianity that has absorbed some tribal traditions.

Land claims

In 1946 the Department of Interior established theIndian Claims Commission The Indian Claims Commission was a judicial relations arbiter between the United States federal government and Native American tribes. It was established under the Indian Claims Act of 1946 by the United States Congress to hear any longstanding clai ...

, to consider compensation for tribes that claimed their lands were seized by the federal government during times of conflict. Tribes seeking settlements had to file claims by August 1961, and both the Oklahoma and Florida Seminoles did so.Bill Drummond, "Indian Land Claims Unsettled 150 Years After Jackson Wars"''LA Times''/''Washington Post'' News Service, printed in ''Sarasota Herald-Tribune,'' 20 October 1978, accessed 13 April 2013 After combining their claims, the Commission awarded the Seminole a total of $16 million in April 1976. It had established that, at the time of the 1823

Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in t ...

, the Seminole exclusively occupied and used 24 million acres in Florida, which they ceded under the treaty. Assuming that most blacks in Florida were escaped slaves, the United States did not recognize the Black Seminoles as legally members of the tribe, nor as free in Florida under Spanish rule. Although the Black Seminoles also owned or controlled land that was seized in this cession, they were not acknowledged in the treaty.

In 1976 the groups struggled on allocation of funds among the Oklahoma and Florida tribes. Based on early 20th-century population records, at which time most of the people were full-blood, the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma was to receive three-quarters of the judgment and the Florida peoples one-quarter. The Miccosukee and allied Traditionals filed suit against the settlement in 1976 to refuse the money; they did not want to give up their claim for return of lands in Florida.

The federal government put the settlement in trust until the court cases could be decided. The Oklahoma and Florida tribes entered negotiations, which was their first sustained contact in the more than a century since removal. In 1990 the settlement was awarded: three-quarters to the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma and one-quarter to the Seminole of Florida, including the Miccosukee. By that time the total settlement was worth $40 million. The tribes have set up judgment trusts, which fund programs to benefit their people, such as education and health.

As a result of the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) about 3,800 Seminole and Black Seminoles were forcibly removed to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

(the modern state of Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

). During the American Civil War, the members and leaders split over their loyalties, with John Chupco

John Chupco (ca. 1821–1881) was a leader of the ''Hvteyievlke'', or Newcomer, Band of the Seminole during the time of their forced relocation to Indian Territory.May, Jon D"Chupco, John (ca. 1821–1881)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclop ...

refusing to sign a treaty with the Confederacy. From 1861 to 1866, he led as chief of the Seminole who supported the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and fought in the Indian Brigade.

The split among the Seminole lasted until 1872. After the war, the United States government negotiated only with the loyal Seminole, requiring the tribe to make a new peace treaty to cover those who allied with the Confederacy, to emancipate the slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and to extend tribal citizenship to those freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

who chose to stay in Seminole territory.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

now has about 16,000 enrolled members, who are divided into a total of fourteen bands; for the Seminole members, these are similar to tribal clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

. The Seminole have a society based on a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

kinship system of descent and inheritance: children are born into their mother's band and derive their status from her people. To the end of the nineteenth century, they spoke mostly Mikasuki and Creek.

Two of the fourteen are "Freedmen Bands," composed of members descended from Black Seminoles, who were legally freed by the US and tribal nations after the Civil War. They have a tradition of extended patriarchal families in close communities. While the elite interacted with the Seminole, most of the Freedmen were involved most closely with other Freedmen. They maintained their own culture, religion and social relationships. At the turn of the 20th century, they still spoke mostly Afro-Seminole Creole

__NOTOC__

Afro-Seminole Creole (ASC) is a dialect of Gullah spoken by Black Seminoles in scattered communities in Oklahoma, Texas, and Northern Mexico.

, a language developed in Florida related to other African-based Creole languages.

The Nation is ruled by an elected council, with two members from each of the fourteen bands, including the Freedmen's bands. The capital is at Wewoka, Oklahoma

Wewoka is a city in Seminole County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 3,271 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Seminole County.

Founded by a freedman, John Coheia, and Black Seminoles in January, 1849, Wewoka is the capital ...

.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Se ...

has had tribal citizenship disputes related to the Seminole Freedmen, both in terms of their sharing in a judgment trust awarded in settlement of a land claim suit, and their membership in the Nation.

Florida Seminole

The remaining few hundred Seminoles survived in the Florida swamplands, avoiding removal. They lived in the Everglades, to isolate themselves from European-Americans. Seminoles continued their distinctive life, such as "clan-based matrilocal residence in scattered thatched-roof chickee camps." Today, the Florida Seminole proudly note the fact that their ancestors were never conquered.

In the 20th century before World War II, the Seminole in Florida divided into two groups; those who were more traditional and those willing to adapt to the reservations. Those who accepted reservation lands and made adaptations achieved federal recognition in 1957 as the

The remaining few hundred Seminoles survived in the Florida swamplands, avoiding removal. They lived in the Everglades, to isolate themselves from European-Americans. Seminoles continued their distinctive life, such as "clan-based matrilocal residence in scattered thatched-roof chickee camps." Today, the Florida Seminole proudly note the fact that their ancestors were never conquered.

In the 20th century before World War II, the Seminole in Florida divided into two groups; those who were more traditional and those willing to adapt to the reservations. Those who accepted reservation lands and made adaptations achieved federal recognition in 1957 as the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized Semi ...

.

Many of those who had kept to traditional ways and spoke the Mikasuki language

The Mikasuki, Hitchiti-Mikasuki, or Hitchiti language is a language or a pair of dialects or closely related languages that belong to the Muskogean languages family. Mikasuki was spoken by around 290 people in southern Florida. Along with the Co ...

organized as the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

, gaining state recognition in 1957 and federal recognition in 1962. (See also Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

, below.) With federal recognition, they gained reservation lands and worked out a separate arrangement with the state for control of extensive wetlands. Other Seminoles not affiliated with either of the federally recognized groups are known as Traditional or Independent Seminoles, known formally as the Council of the Original Miccosukee Simanolee Nation Aboriginal People.

At the time the tribes were recognized, in 1957 and 1962, respectively, they entered into agreements with the US government confirming their sovereignty over tribal lands.

Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole worked hard to adapt, but they were highly affected by the rapidly changing American environment. Natural disasters magnified changes from the governmental drainage project of the Everglades. Residential, agricultural and business development changed the "natural, social, political, and economic environment" of the Seminole. In the 1930s, the Seminole slowly began to move onto federally designated reservation lands within the region. The US government had purchased lands and put them in trust for Seminole use. Initially, few Seminoles had any interest in moving to the reservation land or in establishing more formal relations with the government. Some feared that if they moved onto reservations, they would be forced to move to Oklahoma. Others accepted the move in hopes of stability, jobs promised by the Indian New Deal, or as new

The Seminole worked hard to adapt, but they were highly affected by the rapidly changing American environment. Natural disasters magnified changes from the governmental drainage project of the Everglades. Residential, agricultural and business development changed the "natural, social, political, and economic environment" of the Seminole. In the 1930s, the Seminole slowly began to move onto federally designated reservation lands within the region. The US government had purchased lands and put them in trust for Seminole use. Initially, few Seminoles had any interest in moving to the reservation land or in establishing more formal relations with the government. Some feared that if they moved onto reservations, they would be forced to move to Oklahoma. Others accepted the move in hopes of stability, jobs promised by the Indian New Deal, or as new convert

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

s to Christianity.

Beginning in the 1940s, more Seminoles began to move to the reservations. A major catalyst for this was the conversion of many Seminole to Christianity, following missionary effort spearheaded by the Creek

Beginning in the 1940s, more Seminoles began to move to the reservations. A major catalyst for this was the conversion of many Seminole to Christianity, following missionary effort spearheaded by the Creek Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...