Second Battle Of Kharkov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Second Battle of Kharkov or Operation Fredericus was an

Unknown to the Soviet forces, the German 6th Army, under the newly appointed General Paulus, was issued orders for Operation Fredericus on 30 April 1942. This operation was to crush the Soviet armies within the Izyum salient south of Kharkov, created during the Soviet spring offensives in March and April. The final directive for this offensive, issued on 30 April, gave a start date of 18 May.

The Germans had made a major effort to reinforce

Unknown to the Soviet forces, the German 6th Army, under the newly appointed General Paulus, was issued orders for Operation Fredericus on 30 April 1942. This operation was to crush the Soviet armies within the Izyum salient south of Kharkov, created during the Soviet spring offensives in March and April. The final directive for this offensive, issued on 30 April, gave a start date of 18 May.

The Germans had made a major effort to reinforce

The Red Army offensive began at 6:30 a.m. on 12 May 1942, led by a concentrated hour-long artillery bombardment and a final twenty-minute air attack upon German positions. The ground offensive began with a dual pincer movement from the Volchansk and Barvenkovo salients at 7:30 am. The German defences were knocked out by air raids, artillery-fire and coordinated ground attacks. The fighting was so fierce that the Soviets inched forward their second echelon formations, preparing to throw them into combat as well. Fighting was particularly ferocious near the Soviet village of Nepokrytaia, where the Germans launched three local counter-attacks. The

The Red Army offensive began at 6:30 a.m. on 12 May 1942, led by a concentrated hour-long artillery bombardment and a final twenty-minute air attack upon German positions. The ground offensive began with a dual pincer movement from the Volchansk and Barvenkovo salients at 7:30 am. The German defences were knocked out by air raids, artillery-fire and coordinated ground attacks. The fighting was so fierce that the Soviets inched forward their second echelon formations, preparing to throw them into combat as well. Fighting was particularly ferocious near the Soviet village of Nepokrytaia, where the Germans launched three local counter-attacks. The

On 15 and 16 May, another attempted Soviet offensive in the north met the same resistance encountered on the three first days of the battle. German bastions continued to hold out against Soviet assaults. The major contribution to Soviet frustration in the battle was the lack of heavy artillery, which ultimately prevented the taking of heavily defended positions. One of the best examples of this was the defence of Ternovaya, where defending German units absolutely refused to surrender. The fighting was so harsh that, after advancing an average of five kilometres, the offensive stopped for the day in the north. The next day saw a renewal of the Soviet attack, which was largely blocked by counterattacks by German tanks; the tired Soviet divisions could simply not hold their own against the concerted attacks from the opposition. The south, however, achieved success, much like the earlier days of the battle, although Soviet forces began to face heavier air strikes from German aircraft. The Germans, on the other hand, had spent the day fighting holding actions in both sectors, launching small counterattacks to whittle away at Soviet offensive potential, while continuously moving up reinforcements from the south, including several aircraft squadrons transferred from the Crimea. Poor decisions by the 150th Rifle Division, which had successfully crossed the Barvenkovo River, played a major part in the poor exploitation of the tactical successes of the southern shock group. Timoshenko was unable to choose a point of main effort for his advancing troops, preferring a broad-front approach instead. The Germans traded space for time, which suited their intentions well.

On 15 and 16 May, another attempted Soviet offensive in the north met the same resistance encountered on the three first days of the battle. German bastions continued to hold out against Soviet assaults. The major contribution to Soviet frustration in the battle was the lack of heavy artillery, which ultimately prevented the taking of heavily defended positions. One of the best examples of this was the defence of Ternovaya, where defending German units absolutely refused to surrender. The fighting was so harsh that, after advancing an average of five kilometres, the offensive stopped for the day in the north. The next day saw a renewal of the Soviet attack, which was largely blocked by counterattacks by German tanks; the tired Soviet divisions could simply not hold their own against the concerted attacks from the opposition. The south, however, achieved success, much like the earlier days of the battle, although Soviet forces began to face heavier air strikes from German aircraft. The Germans, on the other hand, had spent the day fighting holding actions in both sectors, launching small counterattacks to whittle away at Soviet offensive potential, while continuously moving up reinforcements from the south, including several aircraft squadrons transferred from the Crimea. Poor decisions by the 150th Rifle Division, which had successfully crossed the Barvenkovo River, played a major part in the poor exploitation of the tactical successes of the southern shock group. Timoshenko was unable to choose a point of main effort for his advancing troops, preferring a broad-front approach instead. The Germans traded space for time, which suited their intentions well.

On 18 May, the situation worsened and

On 18 May, the situation worsened and

The 25 May saw the first major Soviet attempt to break the encirclement. German Major General

The 25 May saw the first major Soviet attempt to break the encirclement. German Major General

Many authors have attempted to pinpoint the reasons for the Soviet defeat. Several Soviet generals have placed the blame on the inability of

Many authors have attempted to pinpoint the reasons for the Soviet defeat. Several Soviet generals have placed the blame on the inability of Khrushchev, Nikita: 'Speech to the Twentieth Party Congress', 1956

/ref> Additionally, the subordinate Soviet generals (especially South-Western Front generals) were just as willing to continue their own winter successes, and much like the German generals, underestimated the strength of their enemies, as pointed out ''a posteriori'' by the commander of the 38th Army, Stalin's willingness to expend recently conscripted armies, which were poorly trained and poorly supplied, illustrated a misconception of realities, both in the capabilities of the Red Army and the subordinate arms of the armed forces, and in the abilities of the Germans to defend themselves and successfully launch a counteroffensive. The latter proved especially true in the subsequent

Stalin's willingness to expend recently conscripted armies, which were poorly trained and poorly supplied, illustrated a misconception of realities, both in the capabilities of the Red Army and the subordinate arms of the armed forces, and in the abilities of the Germans to defend themselves and successfully launch a counteroffensive. The latter proved especially true in the subsequent

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

counter-offensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive is ...

in the region around Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

against the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

Izium

Izium or Izyum ( uk, Ізюм, ; russian: Изюм) is a city on the Donets River in Kharkiv Oblast (province) of eastern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Izium Raion (district). Izium hosts the administration of Izium urban ...

bridgehead offensive conducted 12–28 May 1942, on the Eastern Front during World War II. Its objective was to eliminate the Izium bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

over Seversky Donets

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets, is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv, Done ...

or the "Barvenkovo bulge" (russian: Барвенковский выступ) which was one of the Soviet offensive's staging areas. After a winter counter-offensive that drove German troops away from Moscow but depleted the Red Army's reserves, the Kharkov offensive was a new Soviet attempt to expand upon their strategic initiative, although it failed to secure a significant element of surprise.

On 12 May 1942, Soviet forces under the command of Marshal Semyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

launched an offensive against the German 6th Army from a salient established during the winter counter-offensive. After a promising start, the offensive was stopped on 15 May by massive airstrikes. Critical Soviet errors by several staff officers and by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, who failed to accurately estimate the 6th Army's potential and overestimated their own newly raised forces, facilitated a German pincer attack

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pin ...

on 17 May which cut off three Soviet field armies

A field army (or numbered army or simply army) is a military formation in many armed forces, composed of two or more corps and may be subordinate to an army group. Likewise, air armies are equivalent formation within some air forces, and with ...

from the rest of the front by 22 May. Hemmed into a narrow area, the 250,000-strong Soviet force inside the pocket was exterminated from all sides by German armored

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or f ...

, artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

and machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

firepower as well as 7,700 tonnes of air-dropped bombs. After six days of encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the strategic level, it cannot receive supplies or reinforceme ...

, Soviet resistance ended, with the remaining troops being killed or surrendering.

The battle was an overwhelming German victory, with 280,000 Soviet casualties compared to just 20,000 for the Germans and their allies. The German Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group So ...

pressed its advantage, encircling the Soviet 28th Army on 13 June in Operation Wilhelm

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

and pushing back the 38th and 9th

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

Armies on 22 June in Operation Fridericus II

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

as preliminary operations to Case Blue

Case Blue (German: ''Fall Blau'') was the German Armed Forces' plan for the 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and 24 November 1942, during World War II. The objective was to capture the oil fields of the Cauc ...

, which was launched on 28 June as the main German offensive on the Eastern Front in 1942.

Background

General situation on the Eastern Front

By late February 1942, the Soviet winter counter-offensive, had pushed German forces from Moscow on a broad front and then ended in mutual exhaustion. Stalin was convinced that the Germans were finished and would collapse by the spring or summer 1942, as he said in his speech of 7 November 1941. Stalin decided to exploit this perceived weakness on the Eastern Front by launching a new offensive in the spring. Stalin's decision faced objections from his advisors, including the Chief of theRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

General Staff, General Boris Shaposhnikov

, birth_name = Boris Mikhailovitch Shaposhnikov

, birth_date =

, death_date =

, birth_place = Zlatoust, Ufa GovernorateRussian Empire

, death_place = Moscow, Soviet Union

, placeofburial = Kremlin Wall Necropolis

, placeof ...

, and generals Aleksandr Vasilevsky

Aleksandr Mikhaylovich Vasilevsky ( ru , Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Василе́вский) (30 September 1895 – 5 December 1977) was a Soviet career-officer in the Red Army who attained the rank of Marshal of the Soviet ...

and Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

, who argued for a more defensive strategy. Vasilevsky wrote "Yes, we were hoping for erman reserves to run out but the reality was more harsh than that". According to Zhukov, Stalin believed that the Germans were able to carry out operations simultaneously along two strategic axes, he was sure that the opening of a spring offensives along the entire front would destabilise the German Army, before it had a chance to initiate what could be a mortal offensive blow on Moscow. Despite the caution urged by his generals, Stalin decided to try to keep the German forces off-balance through "local offensives".

Choosing the strategy

After the conclusion of the winter offensive, Stalin and the Soviet Armed Forces General Staff (Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff, a ...

) believed that the eventual German offensives would aim for Moscow, and also with a big offensive to the south, mirroring Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

and Operation Typhoon

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II. It took place between September 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive ...

in 1941. Although the Stavka believed that the Germans had been defeated before Moscow, the seventy divisions which faced Moscow remained a threat. Stalin, most generals and front commanders believed that the principal effort would be a German offensive towards Moscow. Emboldened by the success of the winter offensive, Stalin was convinced that local offensives in the area would wear down German forces, weakening German efforts to mount another operation to take Moscow. Stalin had agreed to prepare the Red Army for an "active strategic defence" but later gave orders for the planning of seven local offensives, stretching from the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

. One area was Kharkov, where action was originally ordered for March.

Early that month, the Stavka issued orders to Southwestern Strategic Direction headquarters for an offensive in the region, after the victories following the Rostov Strategic Offensive Operation

Rostov ( rus, Росто́в, p=rɐˈstof) is a town in Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, one of the oldest in the country and a tourist center of the Golden Ring. It is located on the shores of Lake Nero, northeast of Moscow. Population:

While t ...

(27 November – 2 December 1941) and the Barvenkovo–Lozovaya Offensive Operation (18–31 January 1942) in the Donbas region. The forces of Marshal Semyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

and Lieutenant General Kirill Moskalenko

Kirill Semyonovich Moskalenko (russian: Кирилл Семёнович Москаленко, uk, Кирило Семенович Москаленко; May 11, 1902 – June 17, 1985) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union. A member of the Soviet Arm ...

penetrated German positions along the northern Donets River

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets, is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv, Don ...

, east of Kharkov. Fighting continued into April, with Moskalenko crossing the river and establishing a tenuous bridgehead at Izium

Izium or Izyum ( uk, Ізюм, ; russian: Изюм) is a city on the Donets River in Kharkiv Oblast (province) of eastern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Izium Raion (district). Izium hosts the administration of Izium urban ...

. In the south, the Soviet 6th Army had limited success defending against German forces, which managed to keep a bridgehead of their own on the east bank of the river. Catching the attention of Stalin, it set the pace for the prelude to the eventual offensive intended to reach Pavlohrad

Pavlohrad (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in central east Ukraine, located within the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. It serves as the administrative center of Pavlohrad Raion. Its population is approximately .

The rivers of Vovcha (runs through t ...

and Sinelnikovo

Synelnykove (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in Synelnykove Raion, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (province) of Ukraine, the largest city in the south-eastern part of the region. It serves as the administrative center of the raion. It is named after the ...

and eventually Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

and Poltava

Poltava (, ; uk, Полтава ) is a city located on the Vorskla River in central Ukraine. It is the capital city of the Poltava Oblast (province) and of the surrounding Poltava Raion (district) of the oblast. Poltava is administratively ...

.

By 15 March, Soviet commanders introduced preliminary plans for an offensive towards Kharkov, assisted by a large number of reserves. On 20 March, Timoshenko held a conference in Kupiansk

Kupiansk ( uk, Куп'янськ, ) is a city in Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Kupiansk Raion. It is also an important railroad junction for the oblast. Kupiansk hosts the administrative offices of Kupiansk Ur ...

to discuss the offensive and a report to Moscow, prepared by Timoshenko's chief of staff, Lieutenant General Ivan Baghramian, summed up the conference, although arguably leaving several key intelligence features out. The build-up of Soviet forces in the region of Barvenkovo and Vovchansk

Vovchansk ( uk, Вовчанськ, ) is a Ukrainian city in Chuhuiv Raion of Kharkiv Oblast (province). It hosts the administration of Vovchansk hromada (urban settlement), one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Population:

History

The settlement ...

continued well into the beginning of May. Final details were settled following discussions between Stalin, Stavka and the leadership of the Southwestern Strategic Direction led by Timoshenko throughout March and April, with one of the final Stavka directives issued on 17 April.

Prelude

Soviet order of battle

By 11 May 1942, the Red Army was able to allocate six armies under two fronts, amongst other formations. The Southwestern Front had the 21st Army, 28th Army, 38th Army and the 6th Army. By 11 May, the 21st Tank Corps had been moved into the region with the 23rd Tank Corps, with another 269 tanks. There were also three independent rifle divisions and a rifle regiment from the 270th Rifle Division, concentrated in the area, supported by the 2nd Cavalry Corps in Bogdanovka. TheSoviet Southern Front The Southern Front was a front, a formation about the size of an army group of the Soviet Army during the Second World War. The Southern Front directed military operations during the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina in 1940 and ...

had the 57th and 9th

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

armies, along with thirty rifle divisions, a rifle brigade and the 24th Tank Corps, the 5th Cavalry Corps and three Guards rifle divisions. At its height, the Southern Front could operate eleven guns or mortars per kilometre of front.

Forces regrouping in the sector ran into the '' rasputitsa'', which turned much of the soil into mud. This caused severe delays in the preparations and made reinforcing the Southern and Southwestern Front take longer than expected. Senior Soviet representatives criticised the front commanders for poor management of forces, an inability to stage offensives and for their armchair generalship. Because the regrouping was done so haphazardly, the Germans received some warning of Soviet preparations. Moskalenko, the commander of the 38th Army, placed the blame on the fact that the fronts did not plan in advance to regroup and showed a poor display of front management. (He commented afterwards that it was no surprise that the "German-Fascist command divined our plans".)

Soviet leadership and manpower

The primary Soviet leader was MarshalSemyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

, a veteran of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. Timoshenko had achieved some success at the Battle of Smolensk in 1941 but was eventually defeated. Timoshenko orchestrated the victory at Rostov during the winter counter-attacks and more success in the spring offensive at Kharkov before the battle itself. Overseeing the actions of the army was Military Commissar Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

.

The average Soviet soldier suffered from inexperience. With the Soviet debacle of the previous year ameliorated only by the barest victory at Moscow, most of the original manpower of the Red Army had been killed, wounded or captured by the Germans, with casualties of almost 1,000,000 just from the Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front during World War II. It took place between September 1941 and January ...

. The typical soldier in the Red Army was a conscript and had little to no combat experience, and tactical training was practically nonexistent. Coupled with the lack of trained soldiers, the Red Army also began to suffer from the loss of Soviet industrial areas, and a temporary strategic defence was considered necessary.

The General Chief of Staff, Marshal Vasilevsky, recognised that the Soviet Army of 1942 was not ready to conduct major offensive operations against the well-trained German army, because it did not have quantitative and qualitative superiority and because leadership was being rebuilt after the defeats of 1941. (This analysis is retrospective and is an analysis of Soviet conduct during their strategic offensives in 1942, and even beyond, such as Operation Mars

Operation Mars (Russian: Операция «Марс»), also known as the Second Rzhev-Sychevka Offensive Operation (Russian: Вторая Ржевско-Сычёвская наступательная операция), was the codename fo ...

in October 1942 and the Battle of Târgul Frumos in May 1944.)

German preparations

Unknown to the Soviet forces, the German 6th Army, under the newly appointed General Paulus, was issued orders for Operation Fredericus on 30 April 1942. This operation was to crush the Soviet armies within the Izyum salient south of Kharkov, created during the Soviet spring offensives in March and April. The final directive for this offensive, issued on 30 April, gave a start date of 18 May.

The Germans had made a major effort to reinforce

Unknown to the Soviet forces, the German 6th Army, under the newly appointed General Paulus, was issued orders for Operation Fredericus on 30 April 1942. This operation was to crush the Soviet armies within the Izyum salient south of Kharkov, created during the Soviet spring offensives in March and April. The final directive for this offensive, issued on 30 April, gave a start date of 18 May.

The Germans had made a major effort to reinforce Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group So ...

, and transferred Field Marshal Fedor von Bock

Moritz Albrecht Franz Friedrich Fedor von Bock (3 December 1880 – 4 May 1945) was a German who served in the German Army during the Second World War. Bock served as the commander of Army Group North during the Invasion of Poland in ...

, former commander of Army Group Center

Army Group Centre (german: Heeresgruppe Mitte) was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created on 22 June 1941, as one of three German Army for ...

during Operation Barbarossa and Operation Typhoon. On 5 April 1942, Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

issued Directive 41, which made the south the main area of operations under Case Blue

Case Blue (German: ''Fall Blau'') was the German Armed Forces' plan for the 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and 24 November 1942, during World War II. The objective was to capture the oil fields of the Cauc ...

, the summer campaign, at the expense of the other fronts. The divisions of Army Group South were brought up to full strength in late April and early May. The strategic objective was illustrated after the victories of Erich von Manstein

Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Manstein (born Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski; 24 November 1887 – 9 June 1973) was a German Field Marshal of the ''Wehrmacht'' during the Second World War, who was subsequently convicted of war crimes and ...

and the 11th Army in the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. The main objective remained the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, its oil fields and as a secondary objective, the city of Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

.

The plan to begin Operation Fredericus in April led to more forces being allocated to the area of the German 6th Army. Unknown to the Soviet forces, the German army was regrouping in the center of operations for the offensive around Kharkov. On 10 May, Paulus submitted his final draft of Operation Fredericus and feared a Soviet attack. By then, the German army opposite Timoshenko was ready for the operation towards the Caucasus.

Soviet offensive

Initial success

The Red Army offensive began at 6:30 a.m. on 12 May 1942, led by a concentrated hour-long artillery bombardment and a final twenty-minute air attack upon German positions. The ground offensive began with a dual pincer movement from the Volchansk and Barvenkovo salients at 7:30 am. The German defences were knocked out by air raids, artillery-fire and coordinated ground attacks. The fighting was so fierce that the Soviets inched forward their second echelon formations, preparing to throw them into combat as well. Fighting was particularly ferocious near the Soviet village of Nepokrytaia, where the Germans launched three local counter-attacks. The

The Red Army offensive began at 6:30 a.m. on 12 May 1942, led by a concentrated hour-long artillery bombardment and a final twenty-minute air attack upon German positions. The ground offensive began with a dual pincer movement from the Volchansk and Barvenkovo salients at 7:30 am. The German defences were knocked out by air raids, artillery-fire and coordinated ground attacks. The fighting was so fierce that the Soviets inched forward their second echelon formations, preparing to throw them into combat as well. Fighting was particularly ferocious near the Soviet village of Nepokrytaia, where the Germans launched three local counter-attacks. The Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

's fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

, despite their numerical inferiority, quickly defeated the Soviet air units in the airspace above the battle area, but without bombers, dive-bombers and ground-attack aircraft they could only strafe with their machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s and drop small bombs on the Soviet supply columns and pin down the Soviet infantry. By dark the deepest Soviet advance was . Moskalenko, commander of the 38th Army, discovered the movement of several German reserve units and realised that the attack had been opposed by two German divisions, not the one expected, indicating poor Soviet reconnaissance and intelligence-gathering before the battle. A captured diary of a dead German general alluded to the Germans knowing about Soviet plans in the region.

Next day Paulus obtained three infantry divisions and a panzer division for the defence of Kharkov and the Soviet advance was slow, achieving little success except on the left flank. Bock had warned Paulus not to counter-attack without air support, although this was later reconsidered, when several Soviet tank brigades broke through VIII Corps (General Walter Heitz

Walter Heitz (8 December 1878 – 9 February 1944) was a German general (''Generaloberst'') in the Wehrmacht during World War II who served as President of the Reich Military Court and commanded part of the 6th Army in the Battle of Stalingrad.

...

) in the Volchansk sector, only from Kharkov. In the first 72 hours the 6th Army lost 16 battalions conducting holding actions and local counter-attacks in the heavy rain and mud. By 14 May the Red Army had made impressive gains, but several Soviet divisions were so depleted that they were withdrawn and Soviet tank reserves were needed to defeat the German counter-attacks; German losses were estimated to be minimal, with only 35–70 tanks believed to have been knocked out in the 3rd and 23rd Panzer divisions.

Luftwaffe

Hitler immediately turned to the Luftwaffe to help blunt the offensive. At this point, its close support corps was deployed in theCrimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, taking part in the siege of Sevastopol. Under the command of Wolfram von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Born in 1895 into a fa ...

, the 8th Air Corps __NOTOC__

8th Air Corps (''VIII. Fliegerkorps'') was formed 19 July 1939 in Oppeln as ''Fliegerführer z.b.V.'' ("for special purposes"). It was renamed to the 8th Air Corps on 10 November 1939. The Corps was also known as ''Luftwaffenkommando Sch ...

was initially ordered to deploy to Kharkov from the Crimea, but this order was rescinded. In an unusual move, Hitler kept it in the Crimea, but did not put the corps under the command of ''Luftflotte 4

''Luftflotte'' 4For an explanation of the meaning of Luftwaffe unit designation see Luftwaffe Organisation (Air Fleet 4) was one of the primary divisions of the German Luftwaffe in World War II. It was formed on March 18, 1939, from Luftwaffenkomm ...

'' (Air Fleet 4), which already contained 4th Air Corps, under the command of General Kurt Pflugbeil

__NOTOC__

Kurt Leopold Pflugbeil (9 May 1890 – 31 May 1955) was a German general (General der Flieger) in the Luftwaffe during World War II who commanded 4th Air Corps and Luftflotte 1. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cros ...

, and ''Fliegerführer Süd'' (Flying Command South), a small anti-shipping command based in the Crimea. Instead, he allowed Richthofen to take charge of all operations over Sevastopol. The siege in the Crimea was not over, and the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula

The Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, which commenced with the Soviet Kerch-Feodosia Landing Operation (russian: Керченско-Феодосийская десантная операция, ''Kerchensko-Feodosiyskaya desantnaya operatsiya'') ...

had not yet been won. Hitler was pleased with the progress there and content to keep Richthofen where he was, but he withdrew close support assets from ''Fliegerkorps VIII'' in order to prevent a Soviet breakthrough at Kharkov. The use of the Luftwaffe to compensate for the German Army's lack of firepower suggested to von Richthofen that the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW, "High Command of the Armed Forces") saw the Luftwaffe mainly as a ground support arm. This angered Richthofen who complained that the Luftwaffe was treated as "the army's whore". Now that he was not being redeployed to Kharkov, Richthofen also complained about the withdrawal of his units from the ongoing Kerch

Kerch ( uk, Керч; russian: Керчь, ; Old East Slavic: Кърчевъ; Ancient Greek: , ''Pantikápaion''; Medieval Greek: ''Bosporos''; crh, , ; tr, Kerç) is a city of regional significance on the Kerch Peninsula in the east of t ...

and Sevastopol battles. He felt that the transfer of aerial assets to Kharkov made victory in the Crimea uncertain. In reality, the Soviet units at Kerch were already routed and the Axis position at Sevastopol was comfortable.

Despite von Richthofen's opposition, powerful air support was on its way to bolster the 6th Army and this news boosted German morale. Army commanders, such as Paulus and Bock, placed so much confidence in the Luftwaffe that they ordered their forces not to risk an attack without air support. In the meantime, ''Fliegerkorps IV'', was forced to use every available aircraft. Although meeting more numerous Soviet air forces, the Luftwaffe achieved air superiority and limited the German ground forces' losses to Soviet aviation, but with some crews flying more than 10 missions per day. By 15 May, Pflugbeil was reinforced and received ''Kampfgeschwader 27

'Kampfgeschwader' 27 ''Boelcke'' was a Luftwaffe medium bomber wing of World War II.

Formed in May 1939, KG 27 first saw action in the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. During the Phoney War—September 1939 – April 1940—th ...

'' (Bomber Wing 27, or KG 27), ''Kampfgeschwader 51

''Kampfgeschwader'' 51 "Edelweiss" (KG 51) (Battle Wing 51) was a Luftwaffe bomber wing during World War II.

The unit began forming in May 1939 and completed forming in December 1939, and took no part in the invasion of Poland which start ...

'' (KG 51), ''Kampfgeschwader 55

''Kampfgeschwader'' 55 "Greif" (KG 55 or Battle Wing 55) was a Luftwaffe bomber unit during World War II. was one of the longest serving and well-known in the Luftwaffe. The wing operated the Heinkel He 111 exclusively until 1943, when only ...

'' (KG 55) and ''Kampfgeschwader 76

''Kampfgeschwader 76'' (KG 76) (Battle Wing) was a Luftwaffe bomber Group during World War II. It was one of the few bomber groups that operated throughout the war.

In 1933 Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. To meet the ...

'' (KG 76) equipped with Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

and Heinkel He 111 bombers. ''Sturzkampfgeschwader 77

''Sturzkampfgeschwader'' 77 (StG 77) was a Luftwaffe dive bomber wing during World War II. From the outbreak of war StG 77 distinguished itself in every Wehrmacht major operation until the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942. If the claims mad ...

'' (Dive Bomber Wing 77, or StG 77) also arrived to add direct ground support. Pflugbeil now had 10 bomber, six fighter and four Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

''Stuka'' ''Gruppen'' (Groups). Logistical

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

difficulties meant that only 54.5 per cent were operational at any given time.

German defence

Germanclose air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and moveme ...

made its presence felt immediately on 15 May, forcing units such as the Soviet 38th Army onto the defensive. It ranged over the front, operating dangerously close to the changing frontline. Air interdiction

Air interdiction (AI), also known as deep air support (DAS), is the use of preventive tactical bombing and strafing by combat aircraft against enemy targets that are not an immediate threat, to delay, disrupt or hinder later enemy engagement of fr ...

and direct ground support damaged Soviet supply lines and rear areas, also inflicting large losses on their armoured formations. General Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres, Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and i ...

praised the air strikes as being primarily responsible for breaking the Soviet offensive. The Soviet air force could do very little to stop Pflugbeil's 4th Air Corps. It not only attacked the enemy but also carried out vital supply missions. Bombers dropped supplies to encircled German units, which could continue to hold out until a counter-offensive relieved them. The 4th Air Corps anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

units also used their high-velocity 8.8 cm guns on the Soviet ground forces. Over the course of the 16-day battle the 4th Air Corps played a major role in the German victory, conducting 15,648 sorties (978 per day), dropping 7,700 tonnes of bombs on the Soviet forces and lifting 1,545 tonnes of material to the front.

On 14 May, the Germans continued to attack Soviet positions in the north in localised offensives and by then, the Luftwaffe had gained air superiority over the Kharkov sector, forcing Timoshenko to move his own aircraft forward to counter the bolstered ''Luftflotte 4''. The Luftwaffe won air superiority over their numerically superior, but technically inferior opponents. The air battles depleted the Soviet fighter strength, allowing the German strike aircraft

An attack aircraft, strike aircraft, or attack bomber is a tactical military aircraft that has a primary role of carrying out airstrikes with greater precision than bombers, and is prepared to encounter strong low-level air defenses while pres ...

the chance to influence the land battle even more. Nonetheless, the Soviet forces pushed on, disengaging from several minor battles and changing the direction of their thrusts. However, in the face of continued resistance and local counterattacks, the Soviet attack ebbed, especially when combined with the invariably heavy air raids. By the end of the day, the 28th Army could no longer conduct offensive operations against German positions.

Soviet troops in the northern pincer suffered even more than those in the south. They achieved spectacular success the first three days of combat, with a deep penetration of German positions. The Red Army routed several key German battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s, including many with Hungarian and other foreign soldiers. The success of the Southern Shock group, however, has been attributed to the fact that the early penetrations in the north had directed German reserves there, thus limiting the reinforcements to the south. But, by 14 May, Hitler had briefed General Ewald von Kleist and ordered his 1st Panzer Army to grab the initiative in a bold counteroffensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive i ...

, setting the pace for the final launching of Operation Friderikus.

Second phase of the offensive

On 15 and 16 May, another attempted Soviet offensive in the north met the same resistance encountered on the three first days of the battle. German bastions continued to hold out against Soviet assaults. The major contribution to Soviet frustration in the battle was the lack of heavy artillery, which ultimately prevented the taking of heavily defended positions. One of the best examples of this was the defence of Ternovaya, where defending German units absolutely refused to surrender. The fighting was so harsh that, after advancing an average of five kilometres, the offensive stopped for the day in the north. The next day saw a renewal of the Soviet attack, which was largely blocked by counterattacks by German tanks; the tired Soviet divisions could simply not hold their own against the concerted attacks from the opposition. The south, however, achieved success, much like the earlier days of the battle, although Soviet forces began to face heavier air strikes from German aircraft. The Germans, on the other hand, had spent the day fighting holding actions in both sectors, launching small counterattacks to whittle away at Soviet offensive potential, while continuously moving up reinforcements from the south, including several aircraft squadrons transferred from the Crimea. Poor decisions by the 150th Rifle Division, which had successfully crossed the Barvenkovo River, played a major part in the poor exploitation of the tactical successes of the southern shock group. Timoshenko was unable to choose a point of main effort for his advancing troops, preferring a broad-front approach instead. The Germans traded space for time, which suited their intentions well.

On 15 and 16 May, another attempted Soviet offensive in the north met the same resistance encountered on the three first days of the battle. German bastions continued to hold out against Soviet assaults. The major contribution to Soviet frustration in the battle was the lack of heavy artillery, which ultimately prevented the taking of heavily defended positions. One of the best examples of this was the defence of Ternovaya, where defending German units absolutely refused to surrender. The fighting was so harsh that, after advancing an average of five kilometres, the offensive stopped for the day in the north. The next day saw a renewal of the Soviet attack, which was largely blocked by counterattacks by German tanks; the tired Soviet divisions could simply not hold their own against the concerted attacks from the opposition. The south, however, achieved success, much like the earlier days of the battle, although Soviet forces began to face heavier air strikes from German aircraft. The Germans, on the other hand, had spent the day fighting holding actions in both sectors, launching small counterattacks to whittle away at Soviet offensive potential, while continuously moving up reinforcements from the south, including several aircraft squadrons transferred from the Crimea. Poor decisions by the 150th Rifle Division, which had successfully crossed the Barvenkovo River, played a major part in the poor exploitation of the tactical successes of the southern shock group. Timoshenko was unable to choose a point of main effort for his advancing troops, preferring a broad-front approach instead. The Germans traded space for time, which suited their intentions well.

1st Panzer Army counterattacks

On 17 May, supported by ''Fliegerkorps IV'', the German army took the initiative, as Kleist's 3rd Panzer Corps and 44th Army Corps began a counterattack on the Barvenkovo bridgehead from the area of Aleksandrovka in the south. Aided greatly by air support, Kleist was able to crush Soviet positions and advanced up to ten kilometres in the first day of the attack. Soviet troop and supply convoys were easy targets for ferocious Luftwaffe attacks, possessing few anti-aircraft guns and having left their rail-heads 100 kilometres to the rear. German reconnaissance aircraft monitored enemy movements, directed attack aircraft to Soviet positions and corrected German artillery fire. The response time of the 4th Air Corps to calls for air strikes was excellent, only 20 minutes. Many of the Soviet units were sent to the rear that night to be refitted, while others were moved forward to reinforce tenuous positions across the front. That same day, Timoshenko reported the move to Moscow and asked for reinforcements and described the day's failures. Vasilevsky's attempts to gain approval for a general withdrawal were rejected by Stalin. On 18 May, the situation worsened and

On 18 May, the situation worsened and Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff, a ...

suggested once more stopping the offensive and ordered the 9th Army to break out of the salient. Timoshenko and Khrushchev claimed that the danger coming from the Wehrmacht's Kramatorsk group was exaggerated, and Stalin refused the withdrawal again. The consequences of losing the air battle were also apparent. On 18 May the ''Fliegerkorps IV'' destroyed 130 tanks and 500 motor vehicle

A motor vehicle, also known as motorized vehicle or automotive vehicle, is a self-propelled land vehicle, commonly wheeled, that does not operate on Track (rail transport), rails (such as trains or trams) and is used for the transportation of pe ...

s, while adding another 29 tanks destroyed on 19 May.

On 19 May, Paulus, on orders from Bock, began a general offensive from the area of Merefa

Merefa () is a city in eastern Ukraine. It is located in Kharkiv Raion (district) of Kharkiv Oblast (province). Merefa hosts the administration of Merefa urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Population:

History

It was a village in ...

in the north of the bulge in an attempt to encircle the remaining Soviet forces in the Izium salient. Only then did Stalin authorise Zhukov to stop the offensive and fend off German flanking forces. However, it was already too late. Quickly, the Germans achieved considerable success against Soviet defensive positions. The 20 May saw more of the same, with the German forces closing in from the rear. More German divisions were committed to the battle that day, shattering several Soviet counterparts, allowing the Germans to press forward. The Luftwaffe also intensified operations over the Donets River

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets, is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv, Don ...

to prevent Soviet forces escaping. Ju 87s from StG 77 destroyed five of the main bridges and damaged four more while Ju 88 bombers from '' Kampfgeschwader 3'' (KG 3) inflicted heavy losses on retreating motorised and armoured columns.

Although Timoshenko's forces successfully regrouped on 21 May, he ordered a withdrawal of Army Group Kotenko by the end of 22 May, while he prepared an attack for 23 May, to be orchestrated by the 9th

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

and 57th Armies. Although the Red Army desperately attempted to fend off advancing Wehrmacht and launched local counterattacks to relieve several surrounded units, they generally failed. By the end of May 24, Soviet forces opposite Kharkov had been surrounded by German formations, which had been able to transfer several more divisions to the front, increasing the pressure on the Soviet flanks and finally forcing them to collapse.

Soviet break-out attempts

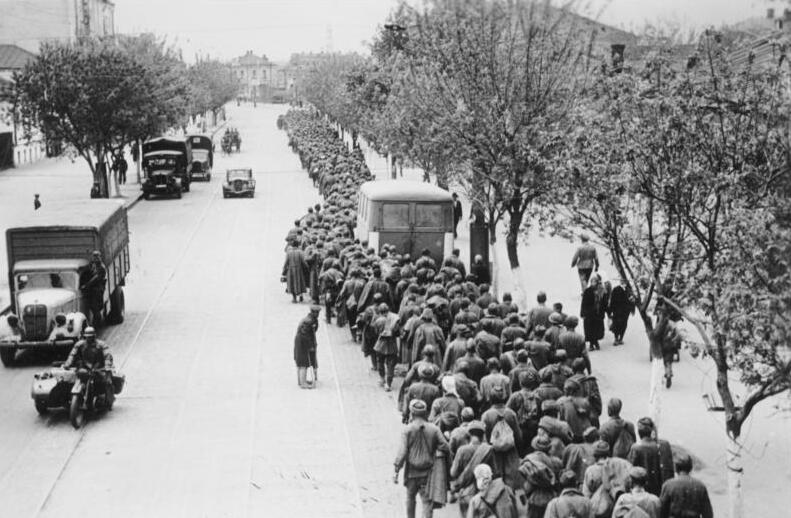

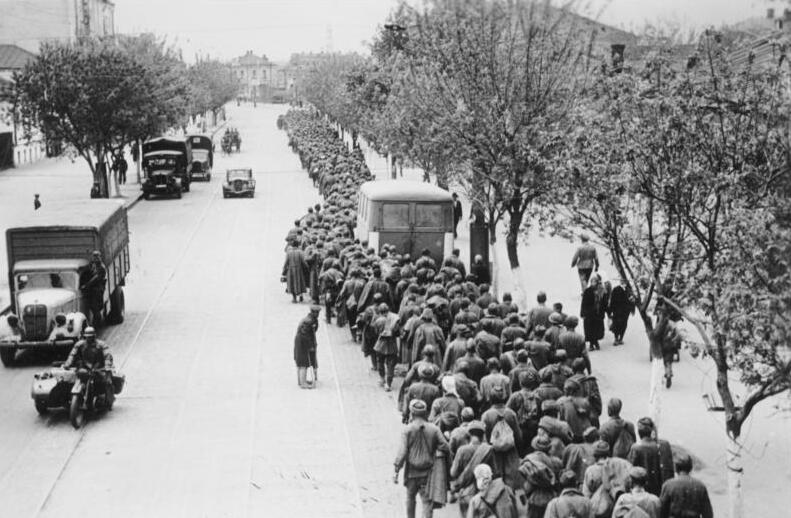

The 25 May saw the first major Soviet attempt to break the encirclement. German Major General

The 25 May saw the first major Soviet attempt to break the encirclement. German Major General Hubert Lanz

Karl Hubert Lanz (22 May 1896 – 15 August 1982) was a German general during the Second World War, in which he led units in the Eastern Front and in the Balkans. After the war, he was tried for war crimes and convicted in the Southeast Case, s ...

described the attacks as gruesome, made ''en masse''. Driven by blind courage, the Soviet soldiers charged at German machine guns with their arms linked, shouting "Urray!". The German machine gunners had no need for accuracy, killing hundreds in quick bursts of fire. In broad daylight, the Luftwaffe, now enjoying complete air supremacy

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of comm ...

and the absence of Soviet anti-aircraft guns, rained down SD2 anti-personnel cluster bombs on the exposed Soviet infantry masses, killing them in droves.

By 26 May, the surviving Red Army soldiers were forced into crowded positions in an area of roughly fifteen square kilometres. Soviet attempts to break through the German encirclement in the east were continuously blocked by tenacious defensive manoeuvres and German air power. Groups of Soviet tanks and infantry that attempted to escape and succeeded in breaking through German lines were caught and destroyed by Ju 87s from StG 77. The flat terrain secured easy observation for the Germans, whose forward observer

An artillery observer, artillery spotter or forward observer (FO) is responsible for directing artillery and mortar fire onto a target. It may be a ''forward air controller'' (FAC) for close air support (CAS) and spotter for naval gunfire sup ...

s directed long-range 10.5 cm and 15 cm artillery fire onto the Soviets from a safe distance to conserve the German infantrymen. More than 200,000 Soviet troops, hundreds of tanks and thousands of trucks and horse-drawn wagons filled the narrow dirt road

A dirt road or track is a type of unpaved road not paved with asphalt, concrete, brick, or stone; made from the native material of the land surface through which it passes, known to highway engineers as subgrade material. Dirt roads are suitable ...

between Krutoiarka and Fedorovka and were under constant German artillery fire and relentless air strikes from Ju 87s, Ju 88s and He 111s. SD-2 cluster munitions killed the unprotected infantry and SC250 bomb

The SC 250 (''Sprengbombe Cylindrisch 250'') was an air-dropped general purpose high-explosive bomb built by Germany during World War II and used extensively during that period. It could be carried by almost all German bomber aircraft, and was use ...

s smashed up the Soviet vehicles and T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank introduced in 1940. When introduced its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was less powerful than its contemporaries while its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against anti-tank weapons. The C ...

tanks. Destroyed vehicles and thousands of dead and dying Red Army soldiers choked up the road and the nearby ravine

A ravine is a landform that is narrower than a canyon and is often the product of streambank erosion.machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

fire and two more Soviet generals were killed in action on the 26th and 27th. Bock personally viewed the carnage from a hill near Lozovenka.

In the face of determined German operations, Timoshenko ordered the official halt of all Soviet offensive manoeuvres on 28 May, while attacks to break out of the encirclement continued until 30 May. Nonetheless, less than one man in ten managed to break out of the "Barvenkovo mousetrap". Hayward gives 75,000 Soviets killed and 239,000 taken prisoner. Beevor puts Soviet prisoners at 240,000 (with the bulk of their armour), while Glantz—citing Krivosheev—gives a total of 277,190 overall Soviet casualties. Both tend to agree on a low German casualty count, with the most formative estimate being at 20,000 dead, wounded and missing. Regardless of the casualties, Kharkov was a major Soviet setback; it put an end to the successes of the Red Army during the winter counteroffensive.

Analysis and conclusions

Many authors have attempted to pinpoint the reasons for the Soviet defeat. Several Soviet generals have placed the blame on the inability of

Many authors have attempted to pinpoint the reasons for the Soviet defeat. Several Soviet generals have placed the blame on the inability of Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff, a ...

and Stalin to appreciate the Wehrmacht's military power on the Eastern Front after their defeats in the winter of 1941–1942 and in the spring of 1942. On the subject, Zhukov sums up in his memoirs that the failure of this operation was quite predictable, since the offensive was organised very ineptly, the risk of exposing the left flank of the Izium salient to German counterattacks being obvious on a map. Still according to Zhukov, the main reason for the stinging Soviet defeat lay in the mistakes made by Stalin, who underestimated the danger coming from German armies in the southwestern sector (as opposed to the Moscow sector) and failed to take steps to concentrate any substantial strategic reserves there to meet any potential German threat. Furthermore, Stalin ignored sensible advice provided by his own General Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, who recommended organising a strong defence in the southwestern sector in order to be able to repulse any Wehrmacht attack. In his famous address to the Twentieth Party Congress about the crimes of Stalin, Khrushchev used the Soviet leader's errors in this campaign as an example, saying: "Contrary to common sense, Stalin rejected our suggestion. He issued the order to continue the encirclement of Kharkov, despite the fact that at this time many f our ownArmy concentrations actually were threatened with encirclement and liquidation... And what was the result of this? The worst we had expected. The Germans surrounded our Army concentrations and as a result he Kharkov counterattack

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

lost hundreds of thousands of our soldiers. This is Stalin's military 'genius'. This is what it cost us."/ref> Additionally, the subordinate Soviet generals (especially South-Western Front generals) were just as willing to continue their own winter successes, and much like the German generals, underestimated the strength of their enemies, as pointed out ''a posteriori'' by the commander of the 38th Army,

Kirill Moskalenko

Kirill Semyonovich Moskalenko (russian: Кирилл Семёнович Москаленко, uk, Кирило Семенович Москаленко; May 11, 1902 – June 17, 1985) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union. A member of the Soviet Arm ...

. The Soviet winter counteroffensive weakened the Wehrmacht, but did not destroy it. As Moskalenko recalls, quoting an anonymous soldier, "these fascists woke up after they hibernated".

Stalin's willingness to expend recently conscripted armies, which were poorly trained and poorly supplied, illustrated a misconception of realities, both in the capabilities of the Red Army and the subordinate arms of the armed forces, and in the abilities of the Germans to defend themselves and successfully launch a counteroffensive. The latter proved especially true in the subsequent

Stalin's willingness to expend recently conscripted armies, which were poorly trained and poorly supplied, illustrated a misconception of realities, both in the capabilities of the Red Army and the subordinate arms of the armed forces, and in the abilities of the Germans to defend themselves and successfully launch a counteroffensive. The latter proved especially true in the subsequent Case Blue

Case Blue (German: ''Fall Blau'') was the German Armed Forces' plan for the 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and 24 November 1942, during World War II. The objective was to capture the oil fields of the Cauc ...

, which led to the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

, though this was the battle in which Paulus faced an entirely different outcome.

The battle had shown the potential of the Soviet armies to successfully conduct an offensive. This battle can be seen as one of the first major instances in which the Soviets attempted to preempt a German summer offensive. This later unfolded and grew as Stavka planned and conducted Operation Mars

Operation Mars (Russian: Операция «Марс»), also known as the Second Rzhev-Sychevka Offensive Operation (Russian: Вторая Ржевско-Сычёвская наступательная операция), was the codename fo ...

, Operation Uranus

Operation Uranus (russian: Опера́ция «Ура́н», Operatsiya "Uran") was the codename of the Soviet Red Army's 19–23 November 1942 strategic operation on the Eastern Front of World War II which led to the encirclement of Axis ...

and Operation Saturn

Operation Little Saturn was a Red Army offensive on the Eastern Front of World War II that led to battles in Don and Chir rivers region in German-occupied Soviet Union territory in 16–30 December 1942.

The success of Operation Uranus, launch ...

. Although only two of the three were victories, it still offers concise and telling evidence of the ability of the Soviets to turn the war in their favour. This finalised itself after the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk was a major World War II Eastern Front engagement between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in the southwestern USSR during late summer 1943; it ultimately became the largest tank battle in history. ...

in July 1943. The Second Battle of Kharkov also had a positive effect on Stalin, who started to trust his commanders and his Chief of Staff more (allowing the latter to have the last word in naming front commanders for instance). After the great purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

in 1937, failing to anticipate the war in 1941, and underestimating German military power in 1942, Stalin finally fully trusted his military.

Within the context of the battle itself, the failure of the Red Army to properly regroup during the prelude to the battle and the ability of the Germans to effectively collect intelligence on Soviet movements played an important role in the outcome. Poor Soviet performance in the north and equally poor intelligence-gathering at the hands of Stavka and front headquarters, also eventually spelled doom for the offensive. Nonetheless, despite this poor performance, it underscored a dedicated evolution of operations and tactics within the Red Army which borrowed and refined the pre-war theory, Soviet deep battle

Deep operation (, ''glubokaya operatsiya''), also known as Soviet Deep Battle, was a military theory developed by the Soviet Union for its armed forces during the 1920s and 1930s. It was a tenet that emphasized destroying, suppressing or disorg ...

.

See also

*First Battle of Kharkov

The First Battle of Kharkov, so named by Wilhelm Keitel, was the 1941 battle for the city of Kharkov, Ukrainian SSR, during the final phase of Operation Barbarossa between the German 6th Army of Army Group South and the Soviet Southwestern F ...

* Third Battle of Kharkov

The Third Battle of Kharkov was a series of battles on the Eastern Front of World War II, undertaken by Army Group South of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Red Army, around the city of Kharkov between 19 February and 15 March 1943. Known to ...

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kharkov, 2nd Battle of Conflicts in 1942 1942 in Ukraine Battles of Kharkov Battles of World War II involving Germany Battles of World War II involving Italy Battles of World War II involving Romania Battles involving the Soviet Union Battles and operations of the Soviet–German War May 1942 events Encirclements in World War II