Seacliff Mental Hospital on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum (often Seacliff Asylum, later Seacliff Mental Hospital) was a

(from the

(from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand) The site is now divided between the Truby King Recreation Reserve, where most of the old buildings have been demolished and most of the area remains dense woodland, and privately owned land where several of the smaller hospital buildings have been renovated completely.''Seacliff asylum's painful and haunting history'' – '' Otago Daily Times'', Saturday 27 January 2007 Seacliff is claimed to be haunted by former patients of what was the country's biggest building at the time.

Structural problems began to manifest themselves even before the first building was completed, and in 1887, only three years after the opening of the main block, a major landslide occurred – predicted as a risk by the surveyors – and affected a temporary building.

Problems with the design's stability could no longer be ignored even at the time, and in 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February of that year, realising that he could be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction – including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself – gave evidence to support their competence. The enquiry decided that it was the architect who carried the ultimate responsibility, and Lawson was found both 'negligent and incompetent'. This may be considered an unreasonable finding as the nature of the site's underlying

Structural problems began to manifest themselves even before the first building was completed, and in 1887, only three years after the opening of the main block, a major landslide occurred – predicted as a risk by the surveyors – and affected a temporary building.

Problems with the design's stability could no longer be ignored even at the time, and in 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February of that year, realising that he could be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction – including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself – gave evidence to support their competence. The enquiry decided that it was the architect who carried the ultimate responsibility, and Lawson was found both 'negligent and incompetent'. This may be considered an unreasonable finding as the nature of the site's underlying

(from the

Treatment of the patients at Seacliff, whether insane,

Treatment of the patients at Seacliff, whether insane,  A nurse working at the hospital in the later years of its operation describes the situation much less critically than Frame, noting that while many patients at Seacliff during her time (1940s) would not have been confined in modern days, the atmosphere was more like that of a large working community. Patients capable of working were asked to help with various duties, partly because of staff shortages in

A nurse working at the hospital in the later years of its operation describes the situation much less critically than Frame, noting that while many patients at Seacliff during her time (1940s) would not have been confined in modern days, the atmosphere was more like that of a large working community. Patients capable of working were asked to help with various duties, partly because of staff shortages in

– McLeod, Kath; Otago Age Concern publication, via Caversham Project,

(from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists newsletter, Dunedin Branch, March/April 2004)

Primarily as a result of worsening ground conditions which progressively affected many of the buildings, the hospital functions of Seacliff were progressively moved to

Primarily as a result of worsening ground conditions which progressively affected many of the buildings, the hospital functions of Seacliff were progressively moved to

Lionel Terry

(from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociat ...

in Seacliff

Seacliff comprises a beach, an estate and a harbour. It lies east of North Berwick, East Lothian, Scotland.

History

The beach and estate command a strategic position at the mouth of the Firth of Forth, and control of the area has been con ...

, New Zealand. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extravagant architecture. It became infamous for construction faults resulting in partial collapse, as well as a 1942 fire which destroyed a wooden outbuilding, claiming 37 lives (39 in other sources), because the victims were trapped in a locked ward.Fire: Seacliff Mental Hospital(from the

Christchurch City Libraries

Christchurch City Libraries is operated by the Christchurch City Council and is a network of 21 libraries and a mobile book bus. Following the 2011 Christchurch earthquake the previous Christchurch Central Library building was demolished, and wa ...

website)

The asylum was less than 20 miles north of Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

and close to the county centre of Palmerston Palmerston may refer to:

People

* Christie Palmerston (c. 1851–1897), Australian explorer

* Several prominent people have borne the title of Viscount Palmerston

** Henry Temple, 1st Viscount Palmerston (c. 1673–1757), Irish nobleman an ...

, in an isolated coastal spot within a forested reserve.The Seacliff Fire(from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand) The site is now divided between the Truby King Recreation Reserve, where most of the old buildings have been demolished and most of the area remains dense woodland, and privately owned land where several of the smaller hospital buildings have been renovated completely.''Seacliff asylum's painful and haunting history'' – '' Otago Daily Times'', Saturday 27 January 2007 Seacliff is claimed to be haunted by former patients of what was the country's biggest building at the time.

History

Planning

The need for a new asylum in the Dunedin area was created by theOtago gold rush

The Otago Gold Rush (often called the Central Otago Gold Rush) was a gold rush that occurred during the 1860s in Central Otago, New Zealand. This was the country's biggest gold strike, and led to a rapid influx of foreign miners to the area – ...

expansion of the city, and triggered by the inadequacy of the Littlebourne Mental Asylum. In 1875, the Provincial Council decided to build a new structure on "a reserve of fine land at Brinn's Point, north of Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a town serving as the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast of Dunedin's city centre.

History

Early Māori settlement

The origi ...

". Initial work was begun in the "dense trackless forest" in 1878, though the Director of the Geological Survey criticised the site location, because he felt that the hillside was unstable.

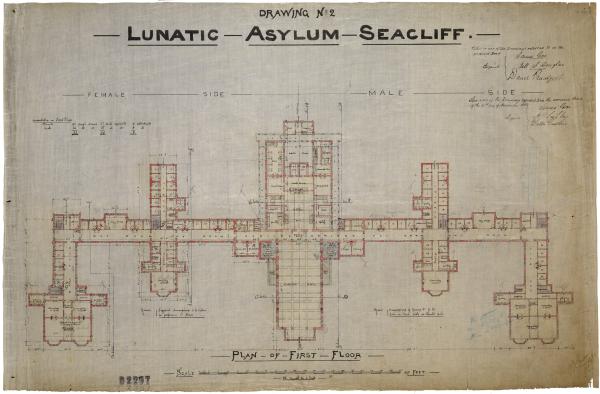

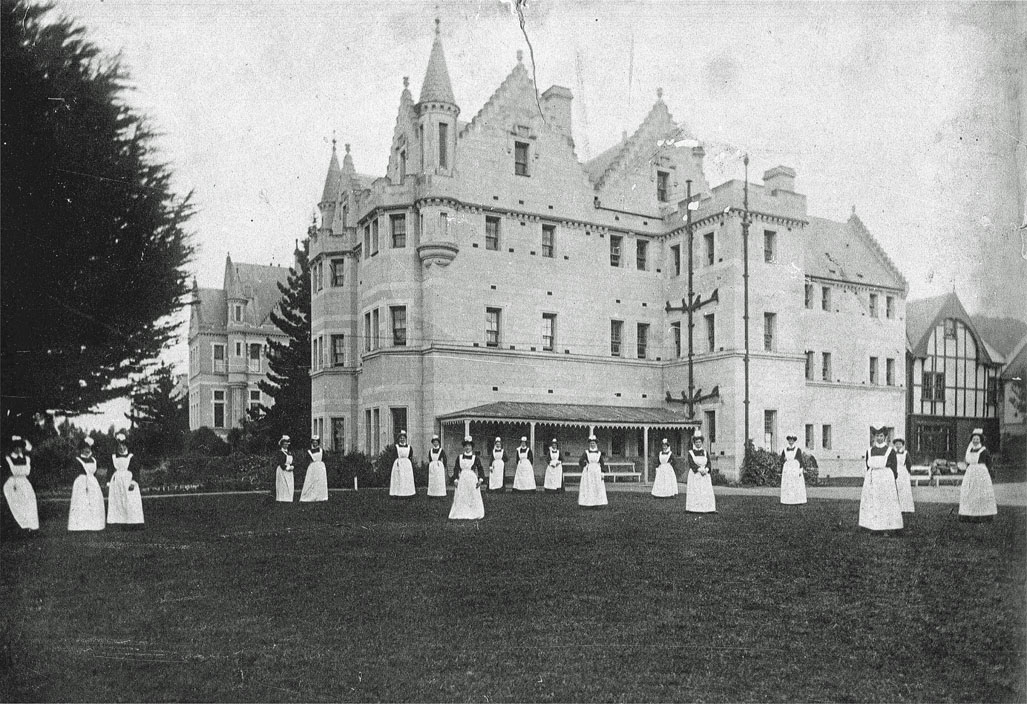

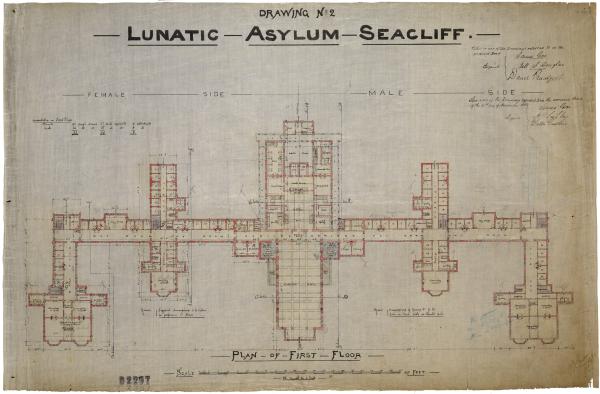

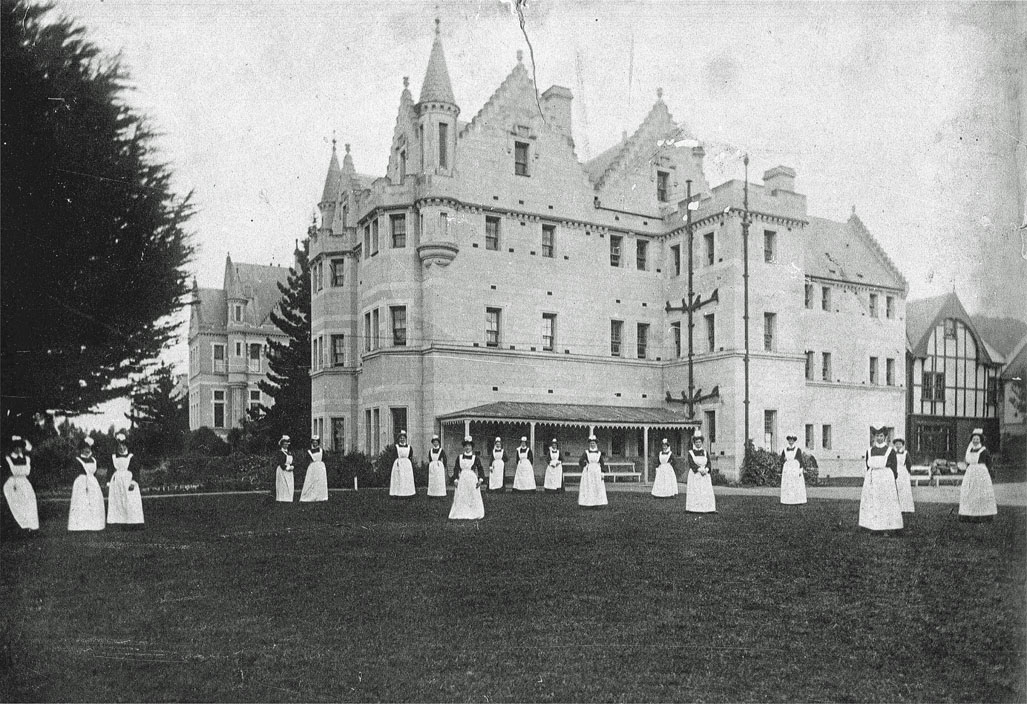

Seacliff Asylum was one of the most important works of Robert Lawson, a New Zealand architect of the 19th century. Known for designing in a range of styles, including the Gothic Revival, he started work on the new asylum in 1874, and was involved with it until the completion of the main block in 1884. At that time, it was New Zealand's largest building, and was to house 500 patients and 50 staff. It had cost £78,000 to construct.

Architecturally, Lawson's work on the asylum was very exuberant, making some of his previous designs look comparatively tame. The asylum had turrets on corbels projecting from nearly every corner, with the gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesth ...

d roof line dominated by a large tower complete with further turrets and a spire. The building contained four and a half million bricks made of local clay on the site and was 225 metres long by 67 metres wide. The great central tower of 50 m height, an essential element of many revivalist designs, was also proposed to double as an observation tower if inmates should try to escape.

It was later said of the building and its (forlorn) location that: "The Victorians might not have wanted their lunatics living with them, but they liked to house them grandly.".

The asylum was progressively added to in later years as it was transformed to function as a working farm, though most of the newer buildings were much simpler wooden structures. Staff lived in separate accommodation close to the wards, and they were able to socialise in nearby Dunedin.

Faults

Structural problems began to manifest themselves even before the first building was completed, and in 1887, only three years after the opening of the main block, a major landslide occurred – predicted as a risk by the surveyors – and affected a temporary building.

Problems with the design's stability could no longer be ignored even at the time, and in 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February of that year, realising that he could be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction – including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself – gave evidence to support their competence. The enquiry decided that it was the architect who carried the ultimate responsibility, and Lawson was found both 'negligent and incompetent'. This may be considered an unreasonable finding as the nature of the site's underlying

Structural problems began to manifest themselves even before the first building was completed, and in 1887, only three years after the opening of the main block, a major landslide occurred – predicted as a risk by the surveyors – and affected a temporary building.

Problems with the design's stability could no longer be ignored even at the time, and in 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February of that year, realising that he could be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction – including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself – gave evidence to support their competence. The enquiry decided that it was the architect who carried the ultimate responsibility, and Lawson was found both 'negligent and incompetent'. This may be considered an unreasonable finding as the nature of the site's underlying bentonite

Bentonite () is an absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite (a type of smectite) which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelling capacity than Ca-m ...

clays was beyond contemporary knowledge of soil mechanics, with Lawson singled out to bear the blame (but this disregards the fact that the site's problems had been pointed out by the surveyors). As New Zealand was at this time suffering an economic recession, Lawson found himself virtually unemployable.

The main block survived until 1959, when it was demolished because of further earth movement.Truby King Recreation Reserve Management Plan(from the

Dunedin City Council

The Dunedin City Council ( mi, Kaunihera ā-Rohe o Ōtepoti) is the local government authority for Dunedin in New Zealand. It is a territorial authority elected to represent the people of Dunedin. Since October 2022, the Mayor of Dunedin is Jul ...

website, 5 August 1998)

Treatment

Treatment of the patients at Seacliff, whether insane,

Treatment of the patients at Seacliff, whether insane, intellectually disabled

Intellectual disability (ID), also known as general learning disability in the United Kingdom and formerly mental retardation, Rosa's Law, Pub. L. 111-256124 Stat. 2643(2010). is a generalized neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by signifi ...

or held in the institution for what would today be classed as simply being difficult, was often very callous, or even outright cruel, a feature of many mental asylums of the times. Janet Frame

Janet Paterson Frame (28 August 1924 – 29 January 2004) was a New Zealand author. She was internationally renowned for her work, which included novels, short stories, poetry, juvenile fiction, and an autobiography, and received numerous awar ...

, a famous New Zealand writer, was held at the asylum during the 1940s and wrongly diagnosed as a schizophrenic

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdr ...

. In her autobiography, she recalled that:

:"The attitude of those in charge, who unfortunately wrote the reports and influenced the treatment, was that of reprimand and punishment, with certain forms of medical treatment being threatened as punishment for failure to 'co-operate' and where 'not co-operate' might mean a refusal to obey an order, say, to go to the doorless lavatories with six others and urinate in public while suffering verbal abuse by the nurse for being unwilling. 'Too fussy are we? Well, Miss Educated, you’ll learn a thing or two here."

Frame describes other patients being beaten for bedwetting, and that all patients tended to continually look for the possibility of running away. She only escaped lobotomy

A lobotomy, or leucotomy, is a form of neurosurgical treatment for psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (e.g. epilepsy) that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex. The surgery causes most of the connections t ...

at Seacliff by fact of her new-found public success (she had won a literary prize while in the institution). Others were not so lucky, being forced to submit to what today would be considered barbaric procedures like the 'unsexing' operation (removal of fallopian tubes, ovaries

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the body. T ...

and clitoris) of Annemarie Anon icin what was at the time considered a 'successful' treatment. Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders.Rudorfer, MV, Henry, ME, Sackeim, HA (2003)"Electroconvulsive th ...

was also widely used.

At the same time, Seacliff was groundbreaking in some parts of its treatment programme, with noted medical reformer Truby King

Sir Frederic Truby King (1 April 1858 – 10 February 1938), generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society.

Early life

King was born in N ...

appointed Medical Superintendent in 1889, a position he held for 30 years. Patients were 'prescribed' fresh air, exercise, good nutrition and productive work (for example, in on-site laundries, gardens, and a forge) as part of their therapeutic regime. King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

is credited as having turned what was essentially conceived as a prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

into an efficient working farm. Another of King's innovations, was his implementation of small dormitories housed in buildings adjacent to the larger asylum. This style of accommodation has been considered the forerunner to the villa system later adopted by all mental health institutions in New Zealand.

A nurse working at the hospital in the later years of its operation describes the situation much less critically than Frame, noting that while many patients at Seacliff during her time (1940s) would not have been confined in modern days, the atmosphere was more like that of a large working community. Patients capable of working were asked to help with various duties, partly because of staff shortages in

A nurse working at the hospital in the later years of its operation describes the situation much less critically than Frame, noting that while many patients at Seacliff during her time (1940s) would not have been confined in modern days, the atmosphere was more like that of a large working community. Patients capable of working were asked to help with various duties, partly because of staff shortages in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Unless considered dangerous, patients were allowed some liberties, such as being allowed to go fishing''Memories are made of this''– McLeod, Kath; Otago Age Concern publication, via Caversham Project,

University of Otago

, image_name = University of Otago Registry Building2.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = University clock tower

, motto = la, Sapere aude

, mottoeng = Dare to be wise

, established = 1869; 152 years ago

, type = Public research collegiate ...

– an activity that provided patients with leisure time, while also helping the fishing business Truby King had long ago established at nearby Karitane

The small town of Karitane is located within the limits of the city of Dunedin in New Zealand, 35 kilometres to the north of the city centre.

Set in rolling country near the mouth of the Waikouaiti River, the town is a popular holiday retreat ...

.

Fatal fire

Around 9:45 pm on 8 December 1942, a fire broke out in Ward 5 of the hospital (also called the 'Simla' building). Ward 5 was a two-storey wooden structure added onto the original construction, holding 39 (41 according to some sources) female patients. All patients had been locked into their rooms or into the 20-bed dormitory, partially becauseWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

had caused a nursing staff shortage. Checks were made only once an hour.

After the fire was noticed by a male attendant, the hospital's firefighters tried to extinguish the flames with water from a close-by hydrant, while two women were saved from rooms that did not have locked shutters. However, the flames were too strong, and after an hour the ward was reduced to ashes, though the fire was kept from spreading to other buildings. All patients who remained in Ward 5 are thought to have died from suffocation from smoke inhalation.

An inquiry into the fire criticised the lack of nursing staff, but praised the firefighters for their prompt and valiant actions, including the quick evacuation of many other patients in nearby threatened buildings. It also remarked on the critical absence of sprinklers (present in other new sections of the institution), and recommended their installation in all psychiatric institutions. The cause of the fire was not found, though there was speculation about an electrical short circuit

A short circuit (sometimes abbreviated to short or s/c) is an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path with no or very low electrical impedance. This results in an excessive current flowing through the circui ...

due to shifting foundations. The disaster remained New Zealand's worst loss of life in a fire until the Ballantyne's store disaster in Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon Rive ...

five years later.New Zealand Disasters – Seacliff Mental Hospital Fire(from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists newsletter, Dunedin Branch, March/April 2004)

Aftermath

Primarily as a result of worsening ground conditions which progressively affected many of the buildings, the hospital functions of Seacliff were progressively moved to

Primarily as a result of worsening ground conditions which progressively affected many of the buildings, the hospital functions of Seacliff were progressively moved to Cherry Farm

Hawksbury, also known as Cherry Farm (and sometimes erroneously as "Evansdale"), is a small residential and industrial area in New Zealand, located beside State Highway 1 between Dunedin and Waikouaiti.Sea Container history. Seadog 1979.

Place n ...

, closing in 1973. The site was subdivided, with the land surrounding the original building site later becoming Truby King Recreation Reserve, having passed into the ownership of Dunedin City in 1991. Around 80% of the reserve is densely wooded, with the area commonly called the 'Enchanted Forest'. The last remaining building in the reserve was demolished due to structural faults in 1992, after an initiative to establish a transport museum

A transport museum is a museum that holds collections of transport items, which are often limited to land transport (road and rail)—including old cars, motorcycles, trucks, trains, trams/streetcars, buses, trolleybuses and coaches—but can als ...

had failed.

The remaining area of hospital buildings outside the Reserve is privately owned. In the summer of 2006-2007, regular guided tours of the hospital grounds were operated in conjunction with the Taieri Gorge Railway

Dunedin Railways (formerly the Taieri Gorge Railway) is the trading name of Dunedin Railways Limited, an operator of a railway line and tourist trains based at Dunedin Railway Station in the South Island of New Zealand. The company is a counci ...

's ''Seasider'' tourist train service.

See also

* List of disasters in New Zealand by death toll *Janet Frame

Janet Paterson Frame (28 August 1924 – 29 January 2004) was a New Zealand author. She was internationally renowned for her work, which included novels, short stories, poetry, juvenile fiction, and an autobiography, and received numerous awar ...

, the most famous of the asylum's patients / inmates

*Truby King

Sir Frederic Truby King (1 April 1858 – 10 February 1938), generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society.

Early life

King was born in N ...

, medical reformer, administrator of the asylum for 30 years

*Lionel Terry

Edward Lionel Terry (1873 – 20 August 1952) was a New Zealand white supremacist and murderer, incarcerated in psychiatric institutions after murdering a Chinese immigrant, Joe Kum Yung, in Wellington, New Zealand in 1905.

Life before New Ze ...

, a schizophrenic white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

murderer who died at Seacliff, after several escapes(from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

References

Further reading

* * {{Hospitals in New Zealand Reportedly haunted locations in New Zealand Hospital buildings completed in 1884 Psychiatric hospitals in New Zealand Buildings and structures in Dunedin Defunct hospitals in New Zealand Hospitals established in 1884 Houses completed in 1884 1973 disestablishments History of Dunedin Robert Lawson buildings 1942 in New Zealand 1880s architecture in New Zealand December 1942 events 1940s in Dunedin 1942 fires in Oceania 1942 disasters in New Zealand