Scrutinium Physico-Medicum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur'' (''A Physico-Medical Examination of the Contagious Pestilence Called the Plague'') is a 1658 work by the

''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur'' (''A Physico-Medical Examination of the Contagious Pestilence Called the Plague'') is a 1658 work by the

Kircher summarised three possible explanations for the plague. The first was the hermetic approaches of

Kircher summarised three possible explanations for the plague. The first was the hermetic approaches of

Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a

Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a

digital copy of ''Scrutinium physico-medicum''

''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur'' (''A Physico-Medical Examination of the Contagious Pestilence Called the Plague'') is a 1658 work by the

''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur'' (''A Physico-Medical Examination of the Contagious Pestilence Called the Plague'') is a 1658 work by the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

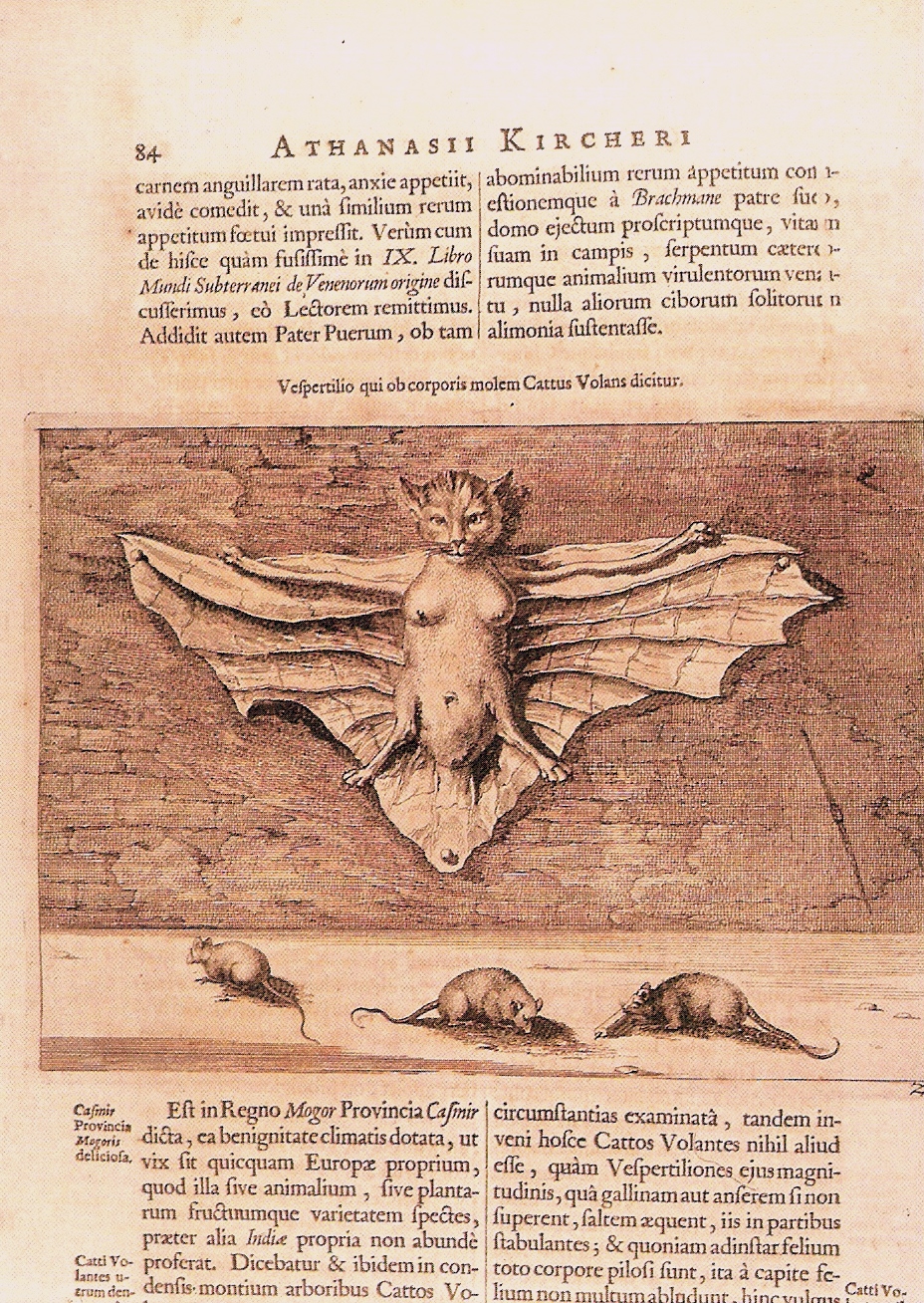

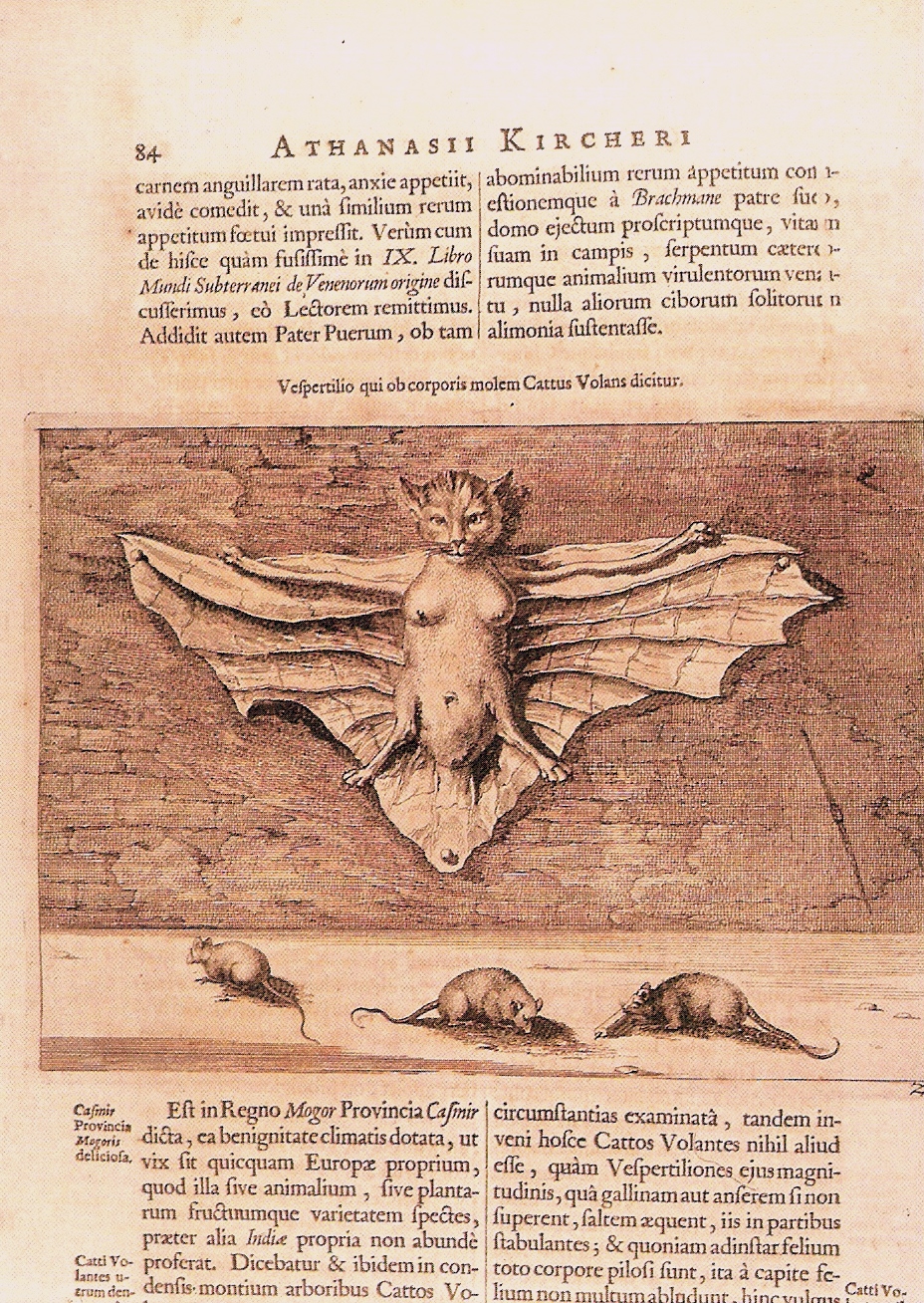

scholar Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans ...

, containing his observations and theories about the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

that struck Rome in the summer of 1656. Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

, and his observations are described in the book. The work was printed on the presses of Vitale Mascardi and dedicated to Pope Alexander VII

Pope Alexander VII ( it, Alessandro VII; 13 February 159922 May 1667), born Fabio Chigi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 April 1655 to his death in May 1667.

He began his career as a vice- papal legate, an ...

.

Background

The plague outbreak in Rome in 1656 killed around 15,000 people in four months. During this period Kircher undertook experiments to try and understand the disease better although there is no evidence that he was directly involved in the medical treatment of the sick. Kircher's previous work, ''Itinerarium exstaticum

''Itinerarium exstaticum quo mundi opificium'' is a 1656 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It is an imaginary dialogue in which an angel named Cosmiel takes the narrator, Theodidactus ('taught by God') on a journey through the planets ...

'' had caused trouble with the Jesuit censors and stirred up controversy. Writing about the plague gave him an opportunity to compliment the new pope, Alexander VII, and move attention away from a work that had caused him difficulties.

The Jesuit Order had a long-established practice of not writing about medical topics. For this reason, the Jesuit censors who reviewed the book - François Duneau, François le Roy and Celidonio Arvizio - originally refused to authorise it for publication. Eventually, after the opinions of a number of medical authorities had been sought, Superior General Goschwin Nickel permitted its printing. The published work included testimonials from the distinguished medical scholars Ioannes Benedictus Sinibaldus, Paulus Zachias and Hieronymous Bardi.

Kircher's theories

Kircher summarised three possible explanations for the plague. The first was the hermetic approaches of

Kircher summarised three possible explanations for the plague. The first was the hermetic approaches of Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He w ...

and Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 drew ...

, the second was the moral explanation for disease, and the third was medical. Kircher agreed that God did send tribulations to afflict mankind, but was most interested in medical research. In ''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum'' Kircher discussed spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise fr ...

as the source of the 'worms' which caused the plague, describing experiments he did with rotting meat and with a mixture of soil and water, which produced microscopic creatures. His conclusion was that "plague in general is a living thing" and that it was transmitted by contact from one person to another.

Kircher theorised that when the ground was opened by caves and fissures, myriads of tiny creatures escaped that carried putrefaction and infected first plants, then the animals that ate them, and eventually, people. Once these creatures infected the human body, they drove out its natural heat. Once the body was chilled, the four humours

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

were overwhelmed with putrefaction, and the victim began spreading disease in their breath.

Kircher recommended the wearing of a dead toad around the neck as a prophylactic against the plague, because he maintained that toads were a scientifically proven magnet attracting the unpleasant vapours that spread the disease.

Significance and Reception

Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a

Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

(which he called a 'smicroscopus'). Reporting that “the putrid blood of those affected by fevers... sso crowded with worms as to well nigh dumbfound me” he concluded that “Plague is in general a living thing”. It is not clear exactly what Kircher saw through his microscope, but it was certainly not the plague bacillus, which was not discovered until 1894.

There were critics of Kircher's ideas, such as Flaminius Gaston, who wrote that Kircher's ideas were such that few people of sound mind embraced them. Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to cha ...

, a member of the Accademia del Cimento

The Accademia del Cimento (Academy of Experiment), an early scientific society, was founded in Florence in 1657 by students of Galileo, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli and Vincenzo Viviani and ceased to exist about a decade later. The foundation of Acade ...

, published ''Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl'Insetti'' (''Experiments on the Generation of Insects'') in 1668. In this work he attempted to reproduce the experiments Kircher claimed to have undertaken in ''Scrutinium physico-medicum'' and found some to be unrepeatable - indeed, Redi questioned whether Kircher had ever even done them himself. Sprinking basil water on powdered scorpion did not generate baby scorpions as Kircher claimed, and he doubted that Kircher had ever successfully generated frogs by mixing ditch dust with water.

Nevertheless Kircher's ideas were taken up by Christian Lange (1619-62), a Leipzig professor, who republished his book with his own preface. A school of medical thinking grew up around Lange and is work in Germany and elsewhere, convinced that contagion was the method of disease transmission as Kircher had argued. Kircher's work was discussed by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and English thinkers persuaded by his views included Frederick Slare, Sir Charles Ent and Walter Charleton. ''Scrutinium Physico-Medicum'' also influenced the thinking of Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

, who believed in contagion theory.

Later editions

Later editions of the work were published in Leipzig by Johannes Baverus in 1659, 1671 and 1674. A Dutch translation was published in Amsterdam by Johannes van Waesbergen in 1669, and a German translation by J.C. Brandan in Augsburg in 1680. The Waesbergern translation carried a frontispiece depicting a woman covered inbuboes

A bubo (Greek βουβών, ''boubṓn'', 'groin') is adenitis or inflammation of the lymph nodes and is an example of reactive lymphadenopathy.

Classification

Buboes are a symptom of bubonic plague and occur as painful swellings in the thighs ...

. Above her hangs a portrait of Kircher. The wolf next to her may be a reference to the Romulus and Remus

In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus (, ) are twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the founding of the city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his fratricide of Remus. The image of a she-wolf suckling the ...

myth, symbolising Rome. She is stepping on a toad, mentioned in the book both as the product of spontaneous generation and as a protective against the plague.

External links

digital copy of ''Scrutinium physico-medicum''

References

{{reflist Obsolete scientific theories 1658 books 1658 in science Athanasius Kircher