The recorded begins with the arrival of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

in the

1st century, when the

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

of

Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Gr ...

reached as far north as the

Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall, known to the Romans as ''Vallum Antonini'', was a turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth. Built some ...

. North of this was

Caledonia

Caledonia (; ) was the Latin name used by the Roman Empire to refer to the part of Great Britain () that lies north of the River Forth, which includes most of the land area of Scotland. Today, it is used as a romantic or poetic name for all ...

, inhabited by the ''Picti'', whose uprisings forced Rome's legions back to

Hadrian's Wall. As Rome finally

withdrew from Britain,

Gaelic raiders called the ''

Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but ...

'' began colonising Western Scotland and Wales. Prior to Roman times,

prehistoric Scotland entered the

Neolithic Era

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

about 4000 BC, the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

about 2000 BC, and the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

around 700 BC.

The Gaelic kingdom of

Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is ...

was founded on the west coast of Scotland in the 6th century. In the following century,

Irish missionaries introduced the previously

pagan Picts to

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

. Following

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

's

Gregorian mission, the Pictish king

Nechtan chose to abolish most Celtic practices in favour of the

Roman rite

The Roman Rite ( la, Ritus Romanus) is the primary liturgical rite of the Latin Church, the largest of the '' sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. It developed in the Latin language in the city of Rome and, while d ...

, restricting Gaelic influence on his kingdom and avoiding war with

Anglian Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

. Towards the end of the 8th century, the

Viking invasions

Viking expansion was the historical movement which led Norse explorers, traders and warriors, the latter known in modern scholarship as Vikings, to sail most of the North Atlantic, reaching south as far as North Africa and east as far as Russi ...

began, forcing the Picts and Gaels to cease their historic hostility to each other and to unite in the 9th century, forming the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a ...

.

The Kingdom of Scotland was united under the

House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináe ...

, whose members fought among each other during frequent disputed successions. The last Alpin king,

Malcolm II, died without a male issue in the early 11th century and the kingdom passed through his daughter's son to the

House of Dunkeld

The House of Dunkeld (in or "of the Caledonians") is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1286. The line is also variously referred to by historians ...

or Canmore. The last Dunkeld king,

Alexander III, died in 1286. He left only his infant granddaughter

Margaret, Maid of Norway

Margaret (, ; March or April 1283 – September 1290), known as the Maid of Norway, was the queen-designate of Scotland from 1286 until her death. As she was never inaugurated, her status as monarch is uncertain and has been debated by historia ...

as heir, who died herself four years later. England, under

Edward I, would take advantage of this questioned succession to launch a series of conquests, resulting in the

Wars of Scottish Independence

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of ...

, as Scotland passed back and forth between the

House of Balliol and the

House of Bruce

Clan Bruce ( gd, Brùs) is a Lowlands Scottish clan. It was a Royal House in the 14th century, producing two kings of Scotland ( Robert the Bruce and David II of Scotland), and a disputed High King of Ireland, Edward Bruce.

Origins

The surna ...

. Scotland's ultimate victory confirmed Scotland as a fully independent and sovereign kingdom.

When

King David II

David II (5 March 1324 – 22 February 1371) was King of Scots from 1329 until his death in 1371. Upon the death of his father, Robert the Bruce, David succeeded to the throne at the age of five, and was crowned at Scone in November 1331, becom ...

died without issue, his nephew

Robert II established the

House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter ...

, which would rule Scotland uncontested for the next three centuries.

James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, Stuart king of Scotland, also inherited the throne of England in 1603, becoming James I of England, and the Stuart kings and queens ruled both independent kingdoms until the

Acts of Union in 1707 merged the two kingdoms into a new state, the

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, w ...

. Ruling until 1714,

Queen Anne was the last Stuart monarch. Since 1714, the succession of the

British monarchs of the houses of

Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

and

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Windsor) has been due to their descent from

James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

of the House of Stuart.

During the

Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

and

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, Scotland became one of the commercial, intellectual and industrial powerhouses of Europe. Later, its

industrial decline following the Second World War was particularly acute. In recent decades Scotland has enjoyed something of a cultural and economic renaissance, fuelled in part by a resurgent

financial services

Financial services are the economic services provided by the finance industry, which encompasses a broad range of businesses that manage money, including credit unions, banks, credit-card companies, insurance companies, accountancy companie ...

sector and the proceeds of

North Sea oil

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid petroleum and natural gas, produced from petroleum reservoirs beneath the North Sea.

In the petroleum industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea an ...

and gas. Since the 1950s, nationalism has become a strong political topic, with serious debates on

Scottish independence, and a referendum in 2014 about leaving the British Union.

Pre-history

People lived in Scotland for at least 8,500 years before Britain's

recorded history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world hi ...

. At times during the last

interglacial period

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene ...

(130,000–70,000 BC) Europe had a climate warmer than today's, and early humans may have made their way to Scotland, with the possible discovery of pre-

Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

axes on

Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) nort ...

and mainland Scotland. Glaciers then scoured their way across most of Britain, and only after the ice retreated did Scotland again become habitable, around 9600 BC.

Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coi ...

hunter-gatherer encampments formed the first known settlements, and archaeologists have dated an encampment near

Biggar to around 12000 BC. Numerous other sites found around Scotland build up a picture of highly mobile boat-using people making tools from bone, stone and antlers. The oldest house for which there is evidence in Britain is the oval structure of wooden posts found at

South Queensferry

Queensferry, also called South Queensferry or simply "The Ferry", is a town to the west of Edinburgh, Scotland. Traditionally a royal burgh of West Lothian, it is administered by the City of Edinburgh council area. It lies ten miles to the nort ...

near the

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meanin ...

, dating from the

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymo ...

period, about 8240 BC. The earliest stone structures are probably the three hearths found at

Jura, dated to about 6000 BC.

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

farming brought permanent settlements. Evidence of these includes the well-preserved stone house at

Knap of Howar on

Papa Westray

Papa Westray () ( sco, Papa Westree), also known as Papay, is one of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, United Kingdom. The fertile soilKeay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) ''Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland''. London. HarperCollins. has long been a draw ...

, dating from around 3500 BC and the village of similar houses at

Skara Brae

Skara Brae is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill on the west coast of Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. Consisting of ten clustered houses, made of flagstones, in earthen dams t ...

on West

Mainland

Mainland is defined as "relating to or forming the main part of a country or continent, not including the islands around it egardless of status under territorial jurisdiction by an entity" The term is often politically, economically and/or dem ...

, Orkney from about 500 years later. The settlers introduced

chambered cairn

A chambered cairn is a burial monument, usually constructed during the Neolithic, consisting of a sizeable (usually stone) chamber around and over which a cairn of stones was constructed. Some chambered cairns are also passage-graves. They are f ...

tombs from around 3500 BC, as at

Maeshowe

Maeshowe (or Maes Howe; non, Orkhaugr) is a Neolithic chambered cairn and passage grave situated on Mainland Orkney, Scotland. It was probably built around . In the archaeology of Scotland, it gives its name to the Maeshowe type of chambered ...

, and from about 3000 BC the many standing stones and circles such as those at

Stenness on the mainland of Orkney, which date from about 3100 BC, of four stones, the tallest of which is in height. These were part of a pattern that developed in many regions across Europe at about the same time.

The creation of cairns and Megalithic monuments continued into the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, which began in Scotland about 2000 BC. As elsewhere in Europe,

hill forts

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post- Rom ...

were first introduced in this period, including the occupation of

Eildon Hill

Eildon Hill lies just south of Melrose, Scotland in the Scottish Borders, overlooking the town. The name is usually pluralised into "the Eildons" or "Eildon Hills", because of its triple peak. The high eminence overlooks Teviotdale to the Sou ...

near Melrose in the

Scottish Borders

The Scottish Borders ( sco, the Mairches, 'the Marches'; gd, Crìochan na h-Alba) is one of 32 council areas of Scotland. It borders the City of Edinburgh, Dumfries and Galloway, East Lothian, Midlothian, South Lanarkshire, West Lot ...

, from around 1000 BC, which accommodated several hundred houses on a fortified hilltop. From the

Early

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

and

Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

there is evidence of cellular round houses of stone, as at

Jarlshof and

Sumburgh in Shetland. There is also evidence of the occupation of

crannog

A crannog (; ga, crannóg ; gd, crannag ) is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually built in lakes and estuarine waters of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Unlike the prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, which were ...

s, roundhouses partially or entirely built on artificial islands, usually in lakes, rivers and estuarine waters.

In the early

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

, from the seventh century BC, cellular houses began to be replaced on the northern isles by simple

Atlantic roundhouses, substantial circular buildings with a dry stone construction. From about 400 BC, more complex Atlantic roundhouses began to be built, as at Howe, Orkney and

Crosskirk, Caithness.

[.] The most massive constructions that date from this era are the circular

broch towers, probably dating from about 200 BC.

[ This period also saw the first wheelhouses, a roundhouse with a characteristic outer wall, within which was a circle of stone piers (bearing a resemblance to the spokes of a wheel), but these would flourish most in the era of Roman occupation. There is evidence for about 1,000 Iron Age hill forts in Scotland, most located below the Clyde-Forth line, which have suggested to some archaeologists the emergence of a society of petty rulers and warrior elites recognisable from Roman accounts.

]

Roman invasion

The surviving pre-Roman accounts of Scotland originated with the

The surviving pre-Roman accounts of Scotland originated with the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης ''Pythéas ho Massaliōtēs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320–306 BC) was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colo ...

of Massalia

Massalia (Greek: Μασσαλία; Latin: Massilia; modern Marseille) was an ancient Greek colony founded ca. 600 BC on the Mediterranean coast of present-day France, east of the river Rhône, by Ionian Greek settlers from Phocaea, in Western ...

, who may have circumnavigated the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

of Albion

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than 'Britain' today. The name for Scot ...

(Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

) and Ierne (Ireland)[Diodorus Siculus' ''Bibliotheca Historica'' Book V. Chapter XXI. Section ]

Greek text

at the Perseus Project

The Perseus Project is a digital library project of Tufts University, which assembles digital collections of humanities resources. Version 4.0 is also known as the "Perseus Hopper", and it is hosted by the Department of Classical Studies. The proj ...

. By the time of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

, who died in AD 79, Roman knowledge of the geography of Scotland had extended to the ''Hebudes'' ( The Hebrides), ''Dumna'' (probably the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

), the Caledonian Forest and the people of the Caledonii, from whom the Romans named the region north of their control Caledonia

Caledonia (; ) was the Latin name used by the Roman Empire to refer to the part of Great Britain () that lies north of the River Forth, which includes most of the land area of Scotland. Today, it is used as a romantic or poetic name for all ...

. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

, possibly drawing on earlier sources of information as well as more contemporary accounts from the Agricolan invasion, identified 18 tribes in Scotland in his ''Geography'', but many of the names are obscure and the geography becomes less reliable in the north and west, suggesting early Roman knowledge of these areas was confined to observations from the sea.

The Roman invasion of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the St ...

began in earnest in AD 43, leading to the establishment of the Roman province of Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Gr ...

in the south. By the year 71, the Roman governor

A Roman governor was an official either elected or appointed to be the chief administrator of Roman law throughout one or more of the many provinces constituting the Roman Empire.

The generic term in Roman legal language was '' Rector provinciae ...

Quintus Petillius Cerialis

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus ( AD 30 — after AD 83), otherwise known as Quintus Petillius Cerialis, was a Roman general and administrator who served in Britain during Boudica's rebellion and went on to participate in the civil wars ...

had launched an invasion of what is now Scotland. In the year 78, Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (; 13 June 40 – 23 August 93) was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribun ...

arrived in Britain to take up his appointment as the new governor and began a series of major incursions. He is said to have pushed his armies to the estuary of the "River Taus" (usually assumed to be the River Tay

The River Tay ( gd, Tatha, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing') is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates i ...

) and established forts there, including a legionary fortress at Inchtuthil

Inchtuthil is the site of a Roman legionary fortress situated on a natural platform overlooking the north bank of the River Tay southwest of Blairgowrie, Perth and Kinross, Scotland (Roman Caledonia).

It was built in AD 82 or 83 as the advanc ...

. After his victory over the northern tribes at Mons Graupius

The Battle of Mons Graupius was, according to Tacitus, a Roman military victory in what is now Scotland, taking place in AD 83 or, less probably, 84. The exact location of the battle is a matter of debate. Historians have long questioned some ...

in 84, a series of forts and towers were established along the Gask Ridge

The Gask Ridge is the modern name given to an early series of fortifications, built by the Romans in Scotland, close to the Highland Line. Modern excavation and interpretation has been pioneered by the Roman Gask Project, with Birgitta Hoffma ...

, which marked the boundary between the Lowland and Highland zones, probably forming the first Roman ''limes'' or frontier in Scotland. Agricola's successors were unable or unwilling to further subdue the far north. By the year 87, the occupation was limited to the Southern Uplands and by the end of the first century the northern limit of Roman expansion was a line drawn between the Tyne Tyne may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Geography

* River Tyne, England

*Port of Tyne, the commercial docks in and around the River Tyne in Tyne and Wear, England

*River Tyne, Scotland

* River Tyne, a tributary of the South Esk River, Tasmania, Australia

Peop ...

and Solway Firth

The Solway Firth ( gd, Tràchd Romhra) is a firth that forms part of the border between England and Scotland, between Cumbria (including the Solway Plain) and Dumfries and Galloway. It stretches from St Bees Head, just south of Whitehaven ...

. The Romans eventually withdrew to a line in what is now northern England, building the fortification known as Hadrian's Wall from coast to coast.[

Around 141, the Romans undertook a reoccupation of southern Scotland, moving up to construct a new '']limes

Limes may refer to:

* the plural form of lime (disambiguation)

* the Latin word for ''limit'' which refers to:

** Limes (Roman Empire)

(Latin, singular; plural: ) is a modern term used primarily for the Germanic border defence or delimitin ...

'' between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, which became the Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall, known to the Romans as ''Vallum Antonini'', was a turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth. Built some ...

. The largest Roman construction inside Scotland, it is a sward

Sward or Swärd may refer to:

* Christian Swärd (born 1987), Swedish ice hockey player

* Marcia P. Sward (1939–2008), American mathematician and nonprofit organization administrator

*Melinda Sward (born 1979), American actress

*Robert Sward

...

-covered wall made of turf around high, with nineteen forts. It extended for . Having taken twelve years to build, the wall was overrun and abandoned soon after 160.["History"](_blank)

''antoninewall.org''. Retrieved 25 July 2008. The Romans retreated to the line of Hadrian's Wall. Roman troops penetrated far into the north of modern Scotland several more times, with at least four major campaigns. The most notable invasion was in 209 when the emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succ ...

led a major force north.[C. M. Hogan]

"Elsick Mounth – Ancient Trackway in Scotland in Aberdeenshire"

in ''The Megalithic Portal'', ed., A. Burnham. Retrieved 24 July 2008. After the death of Severus in 210 they withdrew south to Hadrian's Wall, which would be Roman frontier until it collapsed in the 5th century. By the close of the Roman occupation of southern and central Britain in the 5th century, the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

had emerged as the dominant force in northern Scotland, with the various Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

tribes the Romans had first encountered there occupying the southern half of the country. Roman influence on Scottish culture and history was not enduring.

Post-Roman Scotland

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, there were four groups within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the Picts, with kingdoms between the river Forth and Shetland. In the late 6th century the dominant force was the Kingdom of

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, there were four groups within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the Picts, with kingdoms between the river Forth and Shetland. In the late 6th century the dominant force was the Kingdom of Fortriu

Fortriu ( la, Verturiones; sga, *Foirtrinn; ang, Wærteras; xpi, *Uerteru) was a Pictish kingdom that existed between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but i ...

, whose lands were centred on Strathearn

Strathearn or Strath Earn (, from gd, Srath Èireann) is the strath of the River Earn, in Scotland, extending from Loch Earn in the West to the River Tay in the east.http://www.strathearn.com/st_where.htm Derivation of name Strathearn was on ...

and Menteith

Menteith or Monteith ( gd, Mòine Tèadhaich), a district of south Perthshire, Scotland, roughly comprises the territory between the Teith and the Forth. Earlier forms of its name include ''Meneted'', ''Maneteth'' and ''Meneteth''. (Historically ...

and who raided along the eastern coast into modern England.[ In the west were the Gaelic (]Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically ...

)-speaking people of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is ...

with their royal fortress at Dunadd in Argyll, with close links with the island of Ireland, from whom comes the name Scots.[.] In the south was the British (Brythonic) Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (lit. " Strath of the River Clyde", and Strað-Clota in Old English), was a Brittonic successor state of the Roman Empire and one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Britons, located in the region the Welsh tribes referred to a ...

, descendants of the peoples of the Roman influenced kingdoms of "Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population sp ...

" (Old north), often named Alt Clut, the Brythonic name for their capital at Dumbarton Rock

Dumbarton (; also sco, Dumbairton; ) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven, Dunbartonshire, River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. In 2006, it had an estimated population of 1 ...

. Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was appr ...

, in the south-east. The first English king in the historical record is Ida

Ida or IDA may refer to:

Astronomy

*Ida Facula, a mountain on Amalthea, a moon of Jupiter

*243 Ida, an asteroid

* International Docking Adapter, a docking adapter for the International Space Station

Computing

* Intel Dynamic Acceleration, a tech ...

, who is said to have obtained the throne and the kingdom about 547. Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith, united his kingdom with Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/Cumbric: ''Deywr'' or ''Deifr''; ang, Derenrice or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic *''daru ...

to the south to form Northumbria around the year 604. There were changes of dynasty, and the kingdom was divided, but it was re-united under Æthelfrith's son Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

* Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's '' The Canter ...

(r. 634–642).

Scotland was largely converted to Christianity by Irish-Scots missions associated with figures such as St Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions tended to found monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Partly as a result of these factors, some scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

, in which abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. Th ...

s were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

were more relaxed and there were some significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-7th century.

Rise of the Kingdom of Alba

Conversion to Christianity may have sped a long-term process of gaelicisation of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns, although historians debate whether it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín

Kenneth MacAlpin ( mga, Cináed mac Ailpin, label= Medieval Gaelic, gd, Coinneach mac Ailpein, label=Modern Scottish Gaelic; 810 – 13 February 858) or Kenneth I was King of Dál Riada (841–850), King of the Picts (843–858), and the ...

(Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináe ...

. In 867 AD the Vikings seized the southern half of Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York

Scandinavian York ( non, Jórvík) Viking Yorkshire or Norwegian York is a term used by historians for the south of Northumbria (modern-day Yorkshire) during the period of the late 9th century and first half of the 10th century, when it was do ...

;[.] three years later they stormed the Britons' fortress of Dumbarton and subsequently conquered much of England except for a reduced Kingdom of Wessex,[ leaving the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost encircled. When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, Domnall II (Donald II) was the first man to be called ''rí Alban'' (i.e. ''King of Alba''). The term Scotia was increasingly used to describe the kingdom between North of the Forth and Clyde and eventually the entire area controlled by its kings was referred to as Scotland.

] The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at Brunanburh

The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the point ...

was followed by his retirement as a Culdee

The Culdees ( ga, Céilí Dé, "Spouses of God") were members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England in the Middle Ages. Appearing first in Ireland and subsequently in Scotland, atta ...

monk at St. Andrews. The period between the accession of his successor Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II) was marked by good relations with the Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity and relatively successful expansionary policies. In 945, Máel Coluim I annexed Strathclyde as part of a deal with King Edmund of England, where the kings of Alba had probably exercised some authority since the later 9th century, an event offset somewhat by loss of control in Moray. The reign of King Donnchad I

Donnchad mac Crinain ( gd, Donnchadh mac Crìonain; anglicised as Duncan I, and nicknamed An t-Ilgarach, "the Diseased" or "the Sick"; c. 1001 – 14 August 1040)Broun, "Duncan I (d. 1040)". was king of Scotland ('' Alba'') from 1034 to 1040. ...

(Duncan I) from 1034 was marred by failed military adventures, and he was defeated and killed by MacBeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

, the Mormaer of Moray

The title Earl of Moray, Mormaer of Moray or King of Moray was originally held by the rulers of the Province of Moray, which existed from the 10th century with varying degrees of independence from the Kingdom of Alba to the south. Until 1130 t ...

, who became king in 1040. MacBeth ruled for seventeen years before he was overthrown by Máel Coluim, the son of Donnchad, who some months later defeated MacBeth's step-son

A stepchild is the offspring of one's spouse, but not one's own offspring, either biologically or through adoption.

Stepchildren can come into a family in a variety of ways. A stepchild may be the child of one's spouse from a previous relationshi ...

and successor Lulach to become King Máel Coluim III (Malcolm III).[.]

It was Máel Coluim III, who acquired the nickname "Canmore" (''Cenn Mór'', "Great Chief"), which he passed to his successors and who did most to create the Dunkeld dynasty

The House of Dunkeld (in or "of the Caledonians") is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1286. The line is also variously referred to by historians ...

that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries. Particularly important was his second marriage to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

. This marriage, and raids on northern England, prompted William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, ...

to invade and Máel Coluim submitted to his authority, opening up Scotland to later claims of sovereignty by English kings. When Malcolm died in 1093, his brother Domnall III (Donald III) succeeded him. However, William II of England

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

backed Máel Coluim's son by his first marriage, Donnchad, as a pretender to the throne and he seized power. His murder within a few months saw Domnall restored with one of Máel Coluim sons by his second marriage, Edmund

Edmund is a masculine given name or surname in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings and ...

, as his heir. The two ruled Scotland until two of Edmund's younger brothers returned from exile in England, again with English military backing. Victorious, Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

, the oldest of the three, became king in 1097.[.] Shortly afterwards Edgar and the King of Norway, Magnus Barefoot concluded a treaty recognising Norwegian authority over the Western Isles. In practice Norse control of the Isles was loose, with local chiefs enjoying a high degree of independence. He was succeeded by his brother Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, who reigned 1107–1124.

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ( ...

, who had spent most of his life as a Norman French baron in England. His reign saw what has been characterised as a " Davidian Revolution", by which native institutions and personnel were replaced by English and French ones, underpinning the development of later Medieval Scotland. Members of the Anglo-Norman nobility took up places in the Scottish aristocracy and he introduced a system of feudal land tenure, which produced knight service, castles and an available body of heavily armed cavalry. He created an Anglo-Norman style of court, introduced the office of justicar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

to oversee justice, and local offices of sheriffs to administer localities. He established the first royal burgh

A royal burgh () was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

s in Scotland, granting rights to particular settlements, which led to the development of the first true Scottish towns and helped facilitate economic development as did the introduction of the first recorded Scottish coinage. He continued a process begun by his mother and brothers helping to establish foundations that brought reform to Scottish monasticism based on those at Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, ...

and he played a part in organising diocese on lines closer to those in the rest of Western Europe.

These reforms were pursued under his successors and grandchildren Malcolm IV of Scotland

Malcolm IV ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Eanric, label= Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Eanraig), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 11419 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldes ...

and William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 108 ...

, with the crown now passing down the main line of descent through primogeniture, leading to the first of a series of minorities.[ The benefits of greater authority were reaped by William's son Alexander II and his son Alexander III, who pursued a policy of peace with England to expand their authority in the Highlands and Islands. By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a position to annexe the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the ]Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Kingdom of Norway (872–1397), Norway and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. Through it, Scotland achieved the end of 500 years o ...

with the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had bec ...

in 1266.

The Wars of Independence

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and the death of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway

Margaret (, ; March or April 1283 – September 1290), known as the Maid of Norway, was the queen-designate of Scotland from 1286 until her death. As she was never inaugurated, her status as monarch is uncertain and has been debated by historia ...

in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Duchy of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and D ...

to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

, the man with the strongest claim, who became king in 1292. Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale

Robert V de Brus (Robert de Brus), 5th Lord of Annandale (ca. 1215 – 31 March or 3 May 1295), was a feudal lord, justice and constable of Scotland and England, a regent of Scotland, and a competitor for the Scottish throne in 1290/92 in the ...

, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland. In 1295, John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, known as the Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance (Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting as ...

.

In 1296, Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army at ...

and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as Guardian of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William W ...

in 1298. Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305, he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he owed no allegiance to England.

Rivals John Comyn

John Comyn III of Badenoch, nicknamed the Red (c. 1274 – 10 February 1306), was a leading Scottish baron and magnate who played an important role in the First War of Scottish Independence. He served as Guardian of Scotland after the forced ...

and Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place. On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries. Less than seven weeks later, on 25 March, Bruce was crowned as King. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven

The Battle of Methven took place at Methven, Scotland on 19 June 1306, during the Wars of Scottish Independence. The battlefield was researched to be included in the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland and protected by Historic Sc ...

. Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

in 1314, securing ''de facto'' independence. In 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath, a remonstrance to the Pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected b ...

to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The Declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.

In 1326, what may have been the first full Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council of ...

met. The parliament had evolved from an earlier council of nobility and clergy, the ''colloquium'', constituted around 1235, but perhaps in 1326 representatives of the burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. ...

s – the burgh commissioners – joined them to form the Three Estates. In 1328, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

signed the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton acknowledging Scottish independence under the rule of Robert the Bruce.[M. H. Keen, ''England in the Later Middle Ages: a Political History'' (Routledge, 2nd edn., 2003), pp. 86–8.] However, four years after Robert's death in 1329, England once more invaded on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol (; 1283 – January 1364) was a claimant to the Scottish throne during the Second War of Scottish Independence. With English help, he ruled parts of the kingdom from 1332 to 1356.

Early life

Edward was the eldest son of John ...

, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence.[ Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed.][ Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protégé after the outbreak of the ]Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantag ...

with France.[ In 1341, David II, King Robert's son and heir, was able to return from temporary exile in France. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364.

]

The Stuarts

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ac ...

Robert III. During Robert III's reign (1390–1406), actual power rested largely in the hands of his brother, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany

Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany (c. 1340 – 3 September 1420) was a member of the Scottish royal family who served as regent (at least partially) to three Scottish monarchs ( Robert II, Robert III, and James I). A ruthless politician, Albany w ...

.[S. H. Rigby, ''A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), pp. 301–302.] After the suspicious death (possibly on the orders of the Duke of Albany) of his elder son, David, Duke of Rothesay in 1402, Robert, fearful for the safety of his younger son, the future James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

, sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him en route and he spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after the death of Robert III, regents ruled Scotland: first, the Duke of Albany; and later his son Murdoch

Murdoch ( , ) is an Irish/Scottish given name, as well as a surname. The name is derived from old Gaelic words ''mur'', meaning "sea" and ''murchadh'', meaning "sea warrior". The following is a list of notable people or entities with the name.

...

. When Scotland finally paid the ransom in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride determined to assert his authority.[ Several of the Albany family were executed; but he succeeded in centralising control in the hands of the crown, at the cost of increasing unpopularity, and was assassinated in 1437. His son ]James II James II may refer to:

* James II of Avesnes (died c. 1205), knight of the Fourth Crusade

* James II of Majorca (died 1311), Lord of Montpellier

* James II of Aragon (1267–1327), King of Sicily

* James II, Count of La Marche (1370–1438), King C ...

(reigned 1437–1460), when he came of age in 1449, continued his father's policy of weakening the great noble families, most notably taking on the powerful Black Douglas family that had come to prominence at the time of the Bruce.[

In 1468, the last significant acquisition of Scottish territory occurred when James III was engaged to Margaret of Denmark, receiving the ]Orkney Islands

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) no ...

and the Shetland Islands

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

in payment of her dowry. Berwick upon Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

was captured by England in 1482. With the death of James III in 1488 at the Battle of Sauchieburn

The Battle of Sauchieburn was fought on 11 June 1488, at the side of Sauchie Burn, a stream about south of Stirling, Scotland. The battle was fought between the followers of King James III of Scotland and a large group of rebellious Scottish ...

, his successor James IV successfully ended the quasi-independent rule of the Lord of the Isles

The Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( gd, Triath nan Eilean or ) is a title of Scottish nobility with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title ...

, bringing the Western Isles under effective Royal control for the first time.[ In 1503, he married ]Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

, daughter of Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beaufort, ...

, thus laying the foundation for the 17th-century Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dipl ...

.

Scotland advanced markedly in educational terms during the 15th century with the founding of the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

in 1413, the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

in 1450 and the University of Aberdeen

, mottoeng = The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

, established =

, type = Public research universityAncient university

, endowment = £58.4 million (2021)

, budget ...

in 1495, and with the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools. James IV's reign is often considered to have seen a flowering of Scottish culture under the influence of the European Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

.

In 1512, the Auld Alliance was renewed and under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under

In 1512, the Auld Alliance was renewed and under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

, James IV invaded England in support. The invasion was stopped decisively at the Battle of Flodden Field during which the King, many of his nobles, and a large number of ordinary troops were killed, commemorated by the song '' Flowers of the Forest''. Once again Scotland's government lay in the hands of regents in the name of the infant James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and du ...

.

James V finally managed to escape from the custody of the regents in 1528. He continued his father's policy of subduing the rebellious Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

* So ...

, Western and Northern isles and the troublesome borders.[M. Nicholls, ''A History of the Modern British Isles, 1529–1603: the Two Kingdoms'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 1999), pp. 82–4.] He also continued the French alliance, marrying first the French noblewoman Madeleine of Valois

Madeleine of France or Madeleine of Valois (10 August 1520 – 7 July 1537) was a French princess who briefly became Queen of Scotland in 1537 as the first wife of King James V. The marriage was arranged in accordance with the Treaty of Rouen ...

and then after her death Marie of Guise.[ James V's domestic and foreign policy successes were overshadowed by another disastrous campaign against England that led to defeat at the ]Battle of Solway Moss

The Battle of Solway Moss took place on Solway Moss near the River Esk on the English side of the Anglo-Scottish border in November 1542 between English and Scottish forces.

The Scottish King James V had refused to break from the Catholic Chu ...

(1542).[ James died a short time later, a demise blamed by contemporaries on "a broken heart". The day before his death, he was brought news of the birth of an heir: a daughter, who would become ]Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

.[M. Nicholls, ''A History of the Modern British Isles, 1529–1603: the Two Kingdoms'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 1999), p. 87.]

Once again, Scotland was in the hands of a regent. Within two years, the Rough Wooing

The Rough Wooing (December 1543 – March 1551), also known as the Eight Years' War, was part of the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the 16th century. Following its break with the Roman Catholic Church, England attacked Scotland, partly to break the ...

began, Henry VIII's military attempt to force a marriage between Mary and his son, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

. This took the form of border skirmishing and several English campaigns into Scotland. In 1547, after the death of Henry VIII, forces under the English regent Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (150022 January 1552) (also 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp), also known as Edward Semel, was the eldest surviving brother of Queen Jane Seymour (d. 1537), the third wife of King Henry ...

were victorious at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh

The Battle of Pinkie, also known as the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh ( , ), took place on 10 September 1547 on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland. The last pitched battle between Scotland and England before the Union of the Crow ...

, the climax of the Rough Wooing, and followed up by the occupation of Haddington. Mary was then sent to France at the age of five, as the intended bride of the heir to the French throne. Her mother, Marie de Guise, stayed in Scotland to look after the interests of Mary – and of France – although the Earl of Arran Earl of Arran may refer to:

*Earl of Arran (Scotland), a title in the Peerage of Scotland

*Earl of Arran (Ireland), a title in the Peerage of Ireland

*, a steamship 1860–1871

See also

*

*Earl of Arran and Cambridge

Duke of Hamilton is a t ...

acted officially as regent. Guise responded by calling on French troops, who helped stiffen resistance to the English occupation. By 1550, after a change of regent in England, the English withdrew from Scotland completely.

From 1554 on, Marie de Guise took over the regency and continued to advance French interests in Scotland. French cultural influence resulted in a large influx of French vocabulary into Scots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

. But anti-French sentiment also grew, particularly among Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s, who saw the English as their natural allies. This led to armed conflict at the siege of Leith

The siege of Leith ended a twelve-year encampment of French troops at Leith, the port near Edinburgh, Scotland. The French troops arrived by invitation in 1548 and left in 1560 after an English force arrived to attempt to assist in removing the ...

. Marie de Guise died in June 1560, and soon after the Auld Alliance also ended, with the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh, which provided for the removal of French and English troops from Scotland. The Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Refor ...

took place only days later when the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holy ...

abolished the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

religion and outlawed the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different element ...

.

Meanwhile, Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her queen consort of France. When Francis died in 1560, Mary, now 19, returned to Scotland to take up the government. Despite her private religion, she did not attempt to re-impose Catholicism on her largely Protestant subjects, thus angering the chief Catholic nobles. Her six-year personal reign was marred by a series of crises, largely caused by the intrigues and rivalries of the leading nobles. The murder of her secretary, David Riccio, was followed by that of her unpopular second husband Lord Darnley, and her abduction by and marriage to the

Meanwhile, Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her queen consort of France. When Francis died in 1560, Mary, now 19, returned to Scotland to take up the government. Despite her private religion, she did not attempt to re-impose Catholicism on her largely Protestant subjects, thus angering the chief Catholic nobles. Her six-year personal reign was marred by a series of crises, largely caused by the intrigues and rivalries of the leading nobles. The murder of her secretary, David Riccio, was followed by that of her unpopular second husband Lord Darnley, and her abduction by and marriage to the Earl of Bothwell

Earl of Bothwell was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of Scotland. It was first created for Patrick Hepburn in 1488, and was forfeited in 1567. Subsequently, the earldom was re-created for the 4th Earl's nephew and heir of line, Fr ...

, who was implicated in Darnley's murder. Mary and Bothwell confronted the lords at Carberry Hill

The Battle of Carberry Hill took place on 15 June 1567, near Musselburgh, East Lothian, a few miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland. A number of Scottish lords objected to the rule of Mary, Queen of Scots, after she had married the Earl of Bothw ...

and after their forces melted away, he fled and she was captured by Bothwell's rivals. Mary was imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle

Lochleven Castle is a ruined castle on an island in Loch Leven, in the Perth and Kinross local authority area of Scotland. Possibly built around 1300, the castle was the site of military action during the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–13 ...

, and in July 1567, was forced to abdicate in favour of her infant son James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

. Mary eventually escaped and attempted to regain the throne by force. After her defeat at the Battle of Langside

The Battle of Langside was fought on 13 May 1568 between forces loyal to Mary, Queen of Scots, and forces acting in the name of her infant son James VI. Mary’s short period of personal rule ended in 1567 in recrimination, intrigue, and disa ...

in 1568, she took refuge in England, leaving her young son in the hands of regents. In Scotland the regents fought a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

on behalf of James VI against his mother's supporters. In England, Mary became a focal point for Catholic conspirators and was eventually tried for treason and executed on the orders of her kinswoman Elizabeth I.

Protestant Reformation

During the 16th century, Scotland underwent a

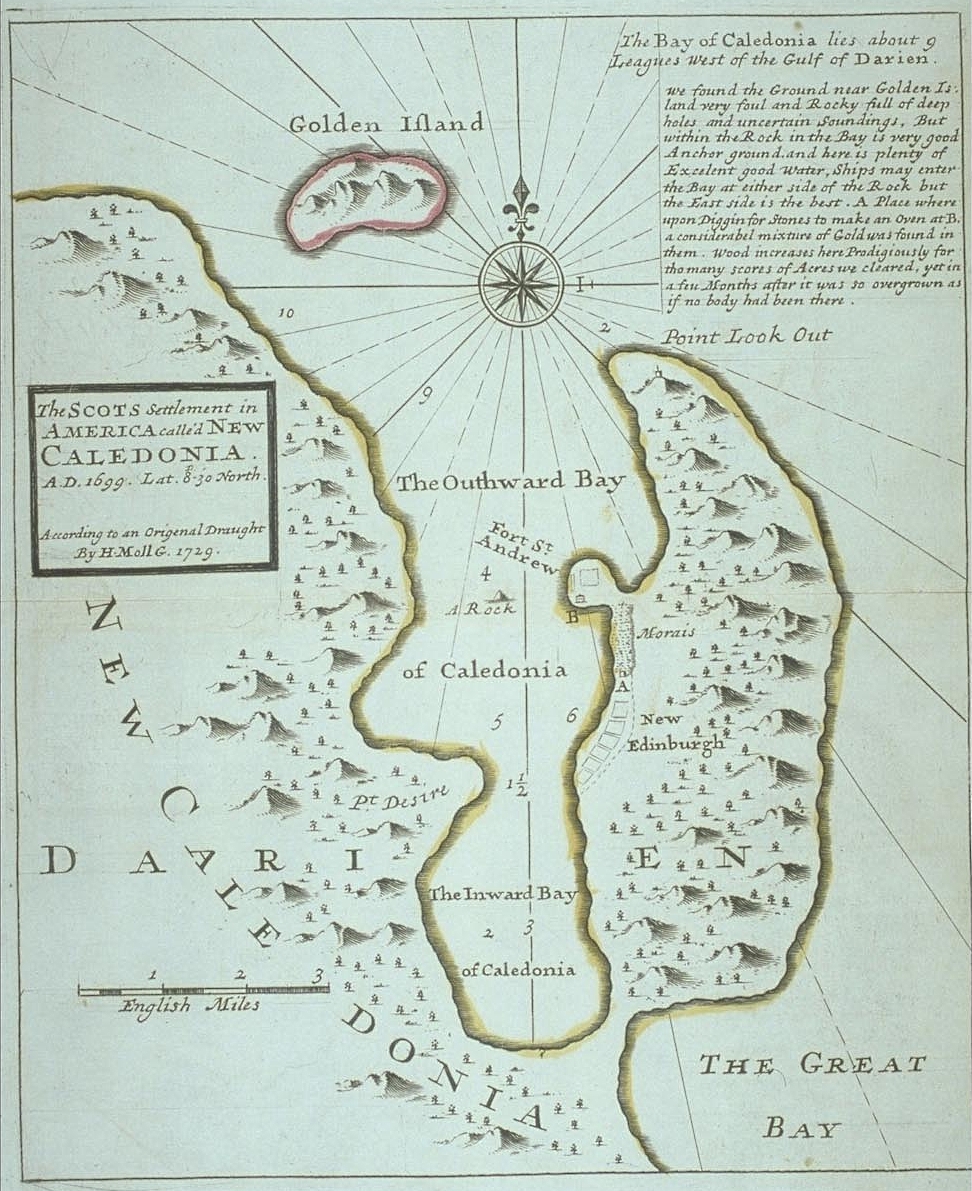

During the 16th century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...