Scotland In The Wars Of The Three Kingdoms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Between 1639 and 1653,

Victory in the 1639 and 1640

Victory in the 1639 and 1640

The

The

From 1644 to 1645 Montrose led the Royalists to six famous victories, defeating covenanting armies larger than his own of roughly 2000 men (except at Kilsyth, where he led approximately 5,000).

In the Autumn of 1644, the Royalists marched across the Highlands to

From 1644 to 1645 Montrose led the Royalists to six famous victories, defeating covenanting armies larger than his own of roughly 2000 men (except at Kilsyth, where he led approximately 5,000).

In the Autumn of 1644, the Royalists marched across the Highlands to  In April Montrose was surprised by General William Baillie after a raid on Dundee, but eluded capture by having his troops double back on the coast road and fleeing inland in a corkscrew retreat. Another Covenanter army under John Urry was hastily assembled and sent against the Royalists. At

In April Montrose was surprised by General William Baillie after a raid on Dundee, but eluded capture by having his troops double back on the coast road and fleeing inland in a corkscrew retreat. Another Covenanter army under John Urry was hastily assembled and sent against the Royalists. At

Ironically, no sooner had the

Ironically, no sooner had the

In June 1649, Montrose was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles also opened negotiations with the Covenanters, now dominated by Argyll's radical Presbyterian "

In June 1649, Montrose was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles also opened negotiations with the Covenanters, now dominated by Argyll's radical Presbyterian "

This military disaster discredited the radical Covenanters known as the

This military disaster discredited the radical Covenanters known as the

Between 1651 and 1654 a royalist rising took place in Scotland.

Between 1651 and 1654 a royalist rising took place in Scotland.

The Campaigns of 1644–45

Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Europe Civil wars of the Early Modern period Wars involving Scotland Wars of the Three Kingdoms 17th-century military history of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

was involved in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, a series of wars starting with the Bishops Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First and ...

(between Scotland and England), the Irish Rebellion of 1641, the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

(and its extension in Scotland), the Irish Confederate Wars, and finally the subjugation of Ireland and Scotland by the English Roundhead

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

.

In Scotland itself, from 1644 to 1645 a Scottish civil war was fought between Scottish Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

—supporters of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

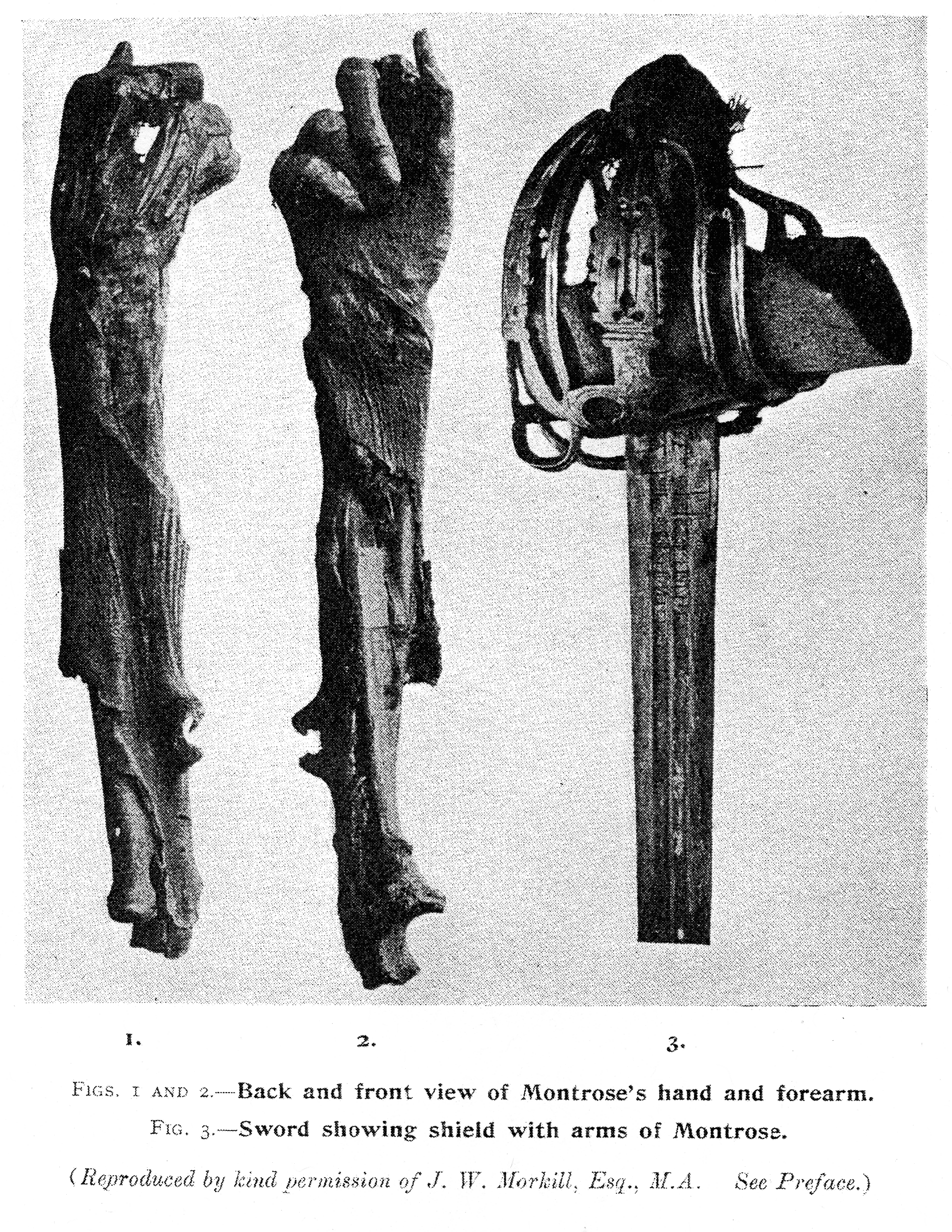

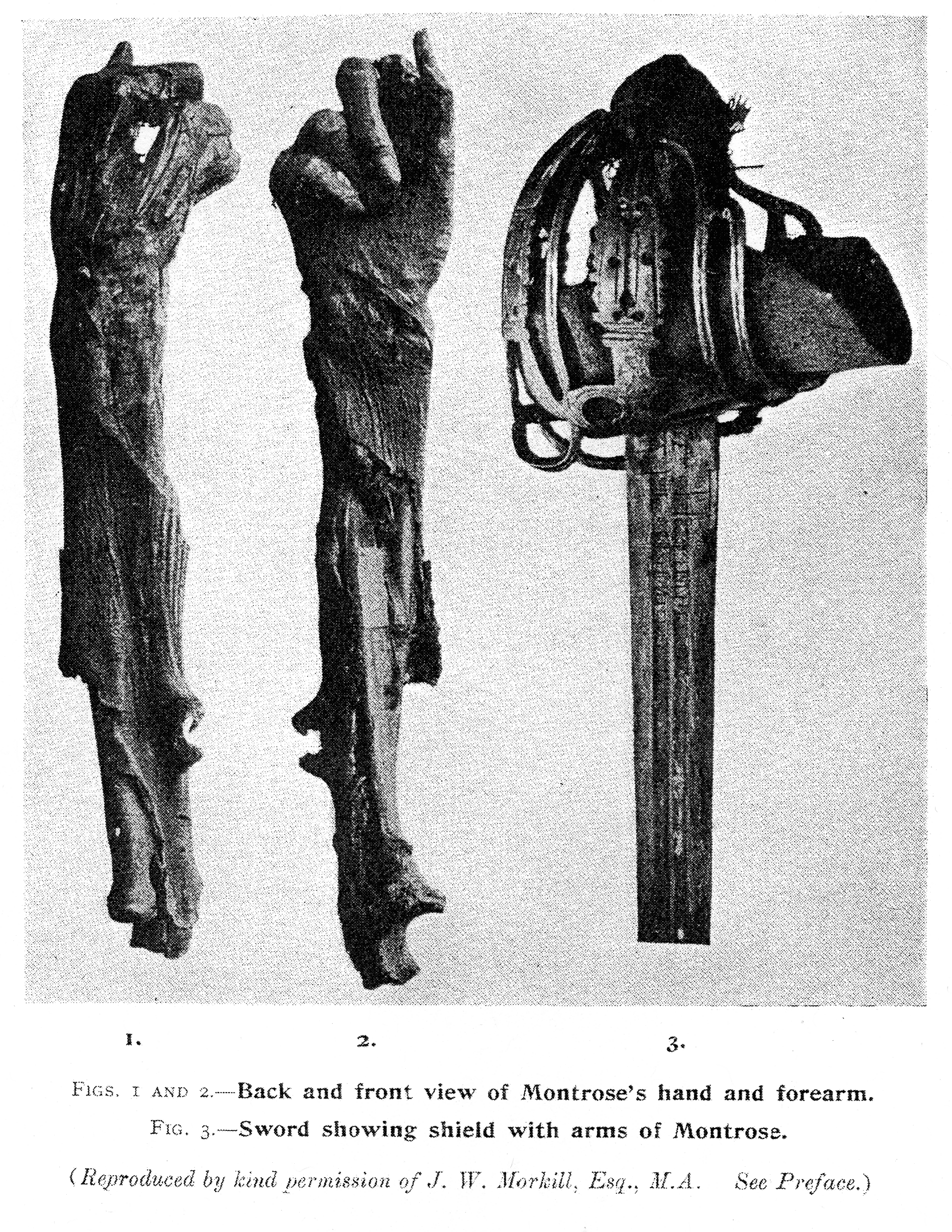

under James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman, poet and soldier, lord lieutenant and later viceroy and captain general of Scotland. Montrose initially joined the Covenanters in the Wars of the Three ...

—and the Covenanters, who had controlled Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

since 1639 and allied with the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

. The Scottish Royalists, aided by Irish troops, had a rapid series of victories in 1644–45, but were eventually defeated by the Covenanters.

The Covenanters then found themselves at odds with the English Parliament, so they crowned Charles II at Scone and thus stated their intention to place him on the thrones of England and Ireland as well. This led to the Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652)

The Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652), also known as the Third Civil War, was the final conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between shifting alliances of religious and political ...

, when Scotland was invaded and occupied by the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

.

Origins of the war – wars in three kingdoms

The war originated in Scottish opposition to religious reforms imposed on theChurch of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

or kirk by Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. This culminated in February 1638 when representatives from all sections of Scottish society agreed a National Covenant, pledging resistance to liturgical 'innovations.' An important factor in the political contest with Charles was the Covenanter belief they were preserving an established and divinely ordained form of religion which he was seeking to alter. The Covenant also expressed wider dissatisfaction with the sidelining of Scotland since the Stuart kings became monarchs of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1603, while the kirk was viewed as a symbol of Scottish independence.

Victory in the 1639 and 1640

Victory in the 1639 and 1640 Bishops Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First and ...

left the Covenanters firmly in control of Scotland but also destabilised Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Widespread opposition to Royal policies meant the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

refused to fund war against the Scots, leading Charles to consider raising an army of Irish Catholics in return for abolishing discriminatory laws against them. This prospect alarmed his enemies in both England and Scotland; when the Covenanters threatened to provide military support for their co-religionists in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, it sparked the Irish Rebellion of 1641, which quickly degenerated into massacres of Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

settlers in Ireland.

The Covenanters responded in April 1642 by sending an army to Ulster led by Robert Monro

Robert Monro (died 1680), was a famous Scottish General, from the Clan Munro of Ross-shire, Scotland. He held command in the Swedish army under Gustavus Adolphus during Thirty Years' War. He also fought for the Scottish Covenanters during the Bi ...

, which engaged in equally bloody reprisals against Catholics. Although both Charles and Parliament supported raising English troops to suppress the Irish rising, neither side trusted the other with their control. A struggle for control of military resources ultimately led to the outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

in August 1642.

Scottish Royalists and Covenanters

The

The Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

established a kirk that was Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

in structure and Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

in doctrine. By 1640, less than 2% of Scots were Catholics, concentrated in places like South Uist

South Uist ( gd, Uibhist a Deas, ; sco, Sooth Uist) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the ...

, controlled by Clanranald, but despite its minority status, fear of "Popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

" remained widespread. Since Calvinists believed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was part of God's plan, the Covenanters committed to "defend the king's person and authority with our goods, bodies, and lives" and the idea of government without a king was inconceivable.

This meant that unlike England, throughout the war all Scots agreed the institution of monarchy was divinely ordered and hence why the Covenanters supported the restoration of Charles I in the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641� ...

, then his son in the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

. Where Covenanters and Scottish Royalists disagreed was the nature and extent of Royal authority versus that of the people, including through the popularly governed Presbyterian church; the relative narrowness of this distinction meant Montrose was not unusual in fighting on both sides.

Royalism was most prominent in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

and Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

, due to a mix of religious, cultural and political reasons; Montrose switched sides because he distrusted Argyll's ambition, fearing he would eventually dominate Scotland and possibly depose the King. Furthermore, the Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The term ...

was a distinct cultural, political and economic region of Scotland. It was Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

in language and customs and at this time was largely outside of the control of the Scottish government. Some Highland clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

preferred the more distant authority of King Charles to the powerful and well organised Lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

based government of the Covenanters.

Clan politics and feuds also played a role; when the Presbyterian Campbell Campbell may refer to:

People Surname

* Campbell (surname), includes a list of people with surname Campbell

Given name

* Campbell Brown (footballer), an Australian rules footballer

* Campbell Brown (journalist) (born 1968), American television ne ...

, led by their chief, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll, 8th Earl of Argyll, Chief of Clan Campbell (March 160727 May 1661) was a Scottish nobleman, politician, and peer. The ''de facto'' head of Scotland's government during most of the conflict of the 1640s and ...

, sided with the Covenanters, their rivals automatically took the opposing side. It should be said some of these factors overlap that spanned the Irish Sea: for instance, the MacDonalds were Catholics, were sworn enemies of the Campbells, and had a strong Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

identity. Historian David Stevenson writes: "It is a moot point whether one should call the MacDonnells of Antrim Scots or Irish... To the MacDonnells themselves the question was largely irrelevant, they had more in common with native Irish and Scots Highlanders, with whom they shared a common Gaelic language and culture than with those who ruled them".

The Irish intervention

Montrose had already tried and failed to lead aRoyalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

uprising by 1644 when he was presented with a ready-made Royalist army. The Irish Confederates

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

, who were loosely aligned with the Royalists, agreed in that year to send an expedition to Scotland. From their point of view, this would tie up Scottish Covenanter troops who would otherwise be used in Ireland or England. The Irish sent 1500 men to Scotland under the command of Alasdair MacColla

Alasdair Mac Colla Chiotaich MacDhòmhnaill (c. 1610 – 13 November 1647), also known by the English variant of his name Sir Alexander MacDonald, was a military officer best known for his participation in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, notably ...

MacDonald, a MacDonald clansman from the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

of Scotland. They included Manus O'Cahan (an Irish cousin to MacColla) and his 500-man regiment. Shortly after landing, the Irish linked up with Montrose at Blair Atholl

Blair Atholl (from the Scottish Gaelic: ''Blàr Athall'', originally ''Blàr Ath Fhodla'') is a village in Perthshire, Scotland, built about the confluence of the Rivers Tilt and Garry in one of the few areas of flat land in the midst of the Gr ...

and proceeded to raise forces from the MacDonalds and other anti-Campbell Highland clans.

The new Royalist army led by Montrose and MacColla was in some respects very formidable. Its Irish and Highland troops were extremely mobile, marching quickly over long distances – even over the rugged Highland terrain – and were capable of enduring very harsh conditions and poor rations. They did not fight in the massed pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

and musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

formations that dominated continental Europe at the time, but fired their muskets in loose order before closing with swords and half-pikes. This tactic was effective in such a wilderness and swept away the poorly trained Covenanter militias that were sent against them. These locally raised levies frequently ran away when faced with a terrifying Highland charge

The Highland charge was a battlefield shock tactic used by the clans of the Scottish Highlands which incorporated the use of firearms.

Historical development

Prior to the 17th century, Highlanders fought in tight formations, led by a heavily ...

, and were slaughtered as they ran.

However, the Royalist army also had major problems: the clans from the west of Scotland could not be persuaded to fight for long away from their homes – seeing their principal enemy as the Campbells rather than the Covenanters, which resulted in fluctuating membership – and the Royalists also lacked cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

, leaving them vulnerable in open country. Montrose overcame some of these disadvantages through his leadership and by taking advantage of the forbidding Highland mountains. Keeping his enemies guessing where he would strike next, Montrose would sally out to attack lowland garrisons and withdraw to the Highlands when threatened by the more numerous enemy. In the safety of the mountains, he could fight on terrain familiar to his army, or lead the Covenanters on wild goose chases.

The year of Royalist triumph and collapse

From 1644 to 1645 Montrose led the Royalists to six famous victories, defeating covenanting armies larger than his own of roughly 2000 men (except at Kilsyth, where he led approximately 5,000).

In the Autumn of 1644, the Royalists marched across the Highlands to

From 1644 to 1645 Montrose led the Royalists to six famous victories, defeating covenanting armies larger than his own of roughly 2000 men (except at Kilsyth, where he led approximately 5,000).

In the Autumn of 1644, the Royalists marched across the Highlands to Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, where they smashed a Covenanter force at the Battle of Tippermuir

The Battle of Tippermuir (also known as the Battle of Tibbermuir) (1 September 1644) was the first battle James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, fought for King Charles I in the Scottish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. During t ...

on 1 September. Shortly afterwards, another Covenanter militia met a similar fate outside Aberdeen on 13 September. Unwisely, Montrose let his men pillage Perth and Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

after taking them, leading to hostility to his forces in an area where Royalist sympathies had been strong.

Following these victories, MacColla insisted on pursuing the MacDonald's war against the Campbells in Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

in western Scotland. In December 1644, the Royalists rampaged through the Campbells' country. During the clan warfare Inveraray

Inveraray ( or ; gd, Inbhir Aora meaning "mouth of the Aray") is a town in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It is on the western shore of Loch Fyne, near its head, and on the A83 road. It is a former royal burgh, the traditional county town of Arg ...

was torched and all armed men were put to the sword; approximately 900 Campbells were killed.

In response to the attack on his clansmen, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll, 8th Earl of Argyll, Chief of Clan Campbell (March 160727 May 1661) was a Scottish nobleman, politician, and peer. The ''de facto'' head of Scotland's government during most of the conflict of the 1640s and ...

assembled the Campbell clansmen to repel the invaders. Montrose, finding himself trapped in the Great Glen

The Great Glen ( gd, An Gleann Mòr ), also known as Glen Albyn (from the Gaelic "Glen of Scotland" ) or Glen More (from the Gaelic ), is a glen in Scotland running for from Inverness on the edge of Moray Firth, in an approximately straight ...

between Argyll and Covenanters advancing from Inverness

Inverness (; from the gd, Inbhir Nis , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness"; sco, Innerness) is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands. Histori ...

, decided on a flanking march through the wintry mountains of Lochaber

Lochaber ( ; gd, Loch Abar) is a name applied to a part of the Scottish Highlands. Historically, it was a provincial lordship consisting of the parishes of Kilmallie and Kilmonivaig, as they were before being reduced in extent by the creation ...

and surprised Argyll at the battle of Inverlochy (2 February 1645). The Covenanters and Campbells were crushed, with losses of 1,500.

Montrose's famous march was acclaimed as "one of the great exploits in the history of British arms" by John Buchan and C.V. Wedgwood. The victory at Inverlochy gave the Royalists control over the western Highlands and attracted other clans and noblemen to their cause. The most important of these were the Gordons, who provided the Royalists with cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

for the first time.

Inverlochy was an important strategic victory for the Royalists, because the Scottish Covenanter army in England was ordered to send a proportion of their force north to help bolster the Covenanter forces in Scotland. This significantly weakened the Scottish army in England and it was only the lack of Royalist infantry and artillery in the north of England that prevented Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cavalr ...

from attacking them. In April 1645, to hinder the northwards movement of English Royalist field artillery, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

led a cavalry raid into the English Midlands. The raid was the first active operation carried out by the newly formed New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

.

In April Montrose was surprised by General William Baillie after a raid on Dundee, but eluded capture by having his troops double back on the coast road and fleeing inland in a corkscrew retreat. Another Covenanter army under John Urry was hastily assembled and sent against the Royalists. At

In April Montrose was surprised by General William Baillie after a raid on Dundee, but eluded capture by having his troops double back on the coast road and fleeing inland in a corkscrew retreat. Another Covenanter army under John Urry was hastily assembled and sent against the Royalists. At Auldearn

Auldearn ( gd, Allt Èireann) is a village situated east of the River Nairn, just outside Nairn in the Highland council area of Scotland. It takes its name from William the Lyon's castle of Eren (''Old Eren''), built there in the 12th century. ...

, near Nairn

Nairn (; gd, Inbhir Narann) is a town and royal burgh in the Highland council area of Scotland. It is an ancient fishing port and market town around east of Inverness, at the point where the River Nairn enters the Moray Firth. It is the tradit ...

, Montrose placed Macdonald and most of infantry in view of the enemy and concealed the cavalry and remaining infantry. Despite Macdonald attacking prematurely, the ruse worked, and Urry was defeated on 9 May.

Another cat-and-mouse game between Bailie and Montrose led to the Battle of Alford

The Battle of Alford was an engagement of the Scottish Civil War. It took place near the village of Alford, Aberdeenshire, on 2 July 1645. During the battle, the Royalist general James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose defeated the forces of ...

on 2 July. Montrose confronted the Covenanters after the latter had forded the Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

, forcing them to fight with the river at their back and on uneven ground. The Royalists triumphed and advanced into the lowlands. Bailie went in pursuit and Montrose waited for him at Kilsyth

Kilsyth (; Scottish Gaelic ''Cill Saidhe'') is a town and civil parish in North Lanarkshire, roughly halfway between Glasgow and Stirling in Scotland. The estimated population is 9,860. The town is famous for the Battle of Kilsyth and the relig ...

. During the ensuing battle the Royalists were inadvertently aided by Argyll and other members of the "Committee of Estates," who ordered Bailie to make a flank march across the front of the Royalist army, which pounced on them and triumphed.

After Kilsyth (15 August), Montrose seemed to have won control of all Scotland: In late 1645, such prominent towns as Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

fell to his forces. The Covenanting government had temporarily collapsed, paying for its over-confidence in defeating Royalist resistance. As the royally commissioned lieutenant-governor and captain-general of Scotland, Montrose used his powers to summon parliament to meet in Glasgow, but the limitations of his triumph soon became clear. King Charles was in no position to join the Royalists in Scotland, and though Montrose wanted to further Royalist objectives by raising troops in the southeast of Scotland and marching on England, MacColla showed that his priorities lay with the war of the MacDonalds against the Campbells and occupied Argyll. The Gordons also returned home, to defend their own lands in the northeast.

During his campaign, Montrose had been unable to attract many lowland royalists to his cause. Even after Kilsyth few joined him, having been alienated by his use of Irish Catholic troops, who were "regarded as barbarians as well as enemies of true religion." Additionally, his covenanting past "left lingering mistrust among royalists."

Montrose, his forces having split up, was surprised and defeated by the Covenanters, led by David Leslie, at the Battle of Philiphaugh

The Battle of Philiphaugh was fought on 13 September 1645 during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms near Selkirk in the Scottish Borders. The Royalist army of the Marquis of Montrose was destroyed by the Covenanter army of Sir David Leslie, ...

. Approximately 100 Irish prisoners, having surrendered upon promise of quarter, were executed, and 300 of the Royalist army's camp followers – mostly women and children – were killed in cold blood. MacColla retreated to Kintyre

Kintyre ( gd, Cinn Tìre, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East and West Loch Tarbert in the north. The region immediately north ...

, where he held out until the following year. In September 1646 Montrose fled to Norway. The Royalist victories in Scotland had evaporated almost overnight owing to the disunited nature of their forces.

The end of the civil war in Scotland

TheFirst English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

had ended in May 1646, when Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

surrendered to the Scottish Covenanter army in England. After failing to persuade the King to take the Covenant, the Scots finally handed him over to the commissioners of the English Parliament (the "Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

") in early 1647. At the same time they received part payment for the service of their army in England, which then returned north. In 1646, Montrose left for Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, while MacColla returned to Ireland with his remaining Irish and Highland troops to re-join the Confederates. Those who had fought for Montrose, particularly the Irish, were massacred by the Covenanters whenever they were captured, in reprisal for the atrocities the Royalists had committed in Argyll.

Scotland and the Second Civil War

Ironically, no sooner had the

Ironically, no sooner had the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

s defeated the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

s at home than they were negotiating with Charles I against the English Parliament. The Covenanters could not get their erstwhile allies to agree on a political and religious settlement to the wars, failing to get Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

established as the official religion in the Three Kingdoms and fearing that the Parliamentarians would threaten Scottish independence. Many Covenanters feared that under Parliament, "our poor country should be made a province of England." A faction of the Covenanters known as the Engagers, led by the Duke of Hamilton

Duke of Hamilton is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in April 1643. It is the senior dukedom in that peerage (except for the Dukedom of Rothesay held by the Sovereign's eldest son), and as such its holder is the premier peer of Sco ...

, therefore sent an army to England to try to restore Charles I in 1648. However, it was routed by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

's New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

at the Battle of Preston. This intervention on behalf of the King caused a brief civil war within the Covenanting movement. The most hardline Presbyterians under the Earl of Argyll rebelled against the main Scottish army under David Leslie. The two factions came to blows at the Battle of Stirling in September 1648, before a peace was hastily negotiated.

Charles was executed by the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" n ...

in 1649, and Hamilton, who had been captured after Preston, was executed soon after. This left the extreme covenanters, still led by Argyll, as the main force in the Kingdom.

Montrose's defeat and death

In June 1649, Montrose was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles also opened negotiations with the Covenanters, now dominated by Argyll's radical Presbyterian "

In June 1649, Montrose was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles also opened negotiations with the Covenanters, now dominated by Argyll's radical Presbyterian "Kirk Party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parlia ...

". Because Montrose had very little support in the lowlands, Charles was willing to disavow his most consistent supporter in order to become a king on terms dictated by the Covenanters. In March 1650 Montrose landed in Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

to take the command of a small force, composed mainly of continental mercenaries, which he had sent on before him. Crossing to the mainland, Montrose tried in vain to raise the clans, and on 27 April he was surprised and routed at the Battle of Carbisdale

The Battle of Carbisdale (also known as Invercarron) took place close to the village of Culrain, Sutherland, Scotland on 27 April 1650 and was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought by the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marq ...

in Ross-shire. After wandering for some time he was surrendered by Neil Macleod of Assynt, to whose protection, in ignorance of Macleod's political enmity, he had entrusted himself. He was brought a prisoner to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, and on 20 May sentenced to death by the Parliament. He was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

on the 21st, with Wishart's laudatory biography of him put round his neck. To the last he protested that he was a real Covenanter and a loyal subject.

Anglo-Scottish war, 1650–1652

In spite of their conflict with the Scottish Royalists, the Covenanters then committed themselves to the cause of Charles II, signing theTreaty of Breda (1650)

The Treaty of Breda (1650) was signed on 1 May 1650 between Charles II (King in exile of England, Scotland and Ireland) and the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Background

The Scots Covenanters had taken the side of ...

with him in the hope of securing an independent Presbyterian Scotland free of English Parliamentary interference. Charles landed in Scotland at Garmouth

Garmouth ( gd, Geàrr Magh narrow plain" spurious gd, Gairmeach, A' Ghairmich; sco, Gairmou', Garmo), is a village in Moray, north east Scotland. It is situated close to the mouth of the River Spey and the coast of the Moray Firth at nearb ...

in Moray

Moray () gd, Moireibh or ') is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland.

Between 1975 ...

on 23 June 1650 and signed the 1638 Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League immediately after coming ashore.

The threat posed by King Charles II with his new Covenanter allies was considered to be the greatest facing the new English Republic so Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

left some of his lieutenants in Ireland to continue the suppression of the Irish Royalists and returned to England in May. He arrived in Scotland on 22 July 1650, advancing along the east coast towards Edinburgh. By the end of August, his army was reduced by disease and running out of supplies, so he was forced to order a retreat towards his base at the port of Dunbar. A Scottish Covenanter army under the command of David Leslie had been shadowing his progress. Seeing some of Cromwell's sick troops being taken on board the waiting ships, Leslie made ready to attack what he believed was a weakened remnant (though some historians report that he was ordered to fight against his better judgment by the Covenanter General Assembly). Cromwell seized the opportunity, and the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

inflicted a crushing defeat on the Scots at the subsequent Battle of Dunbar on 3 September. Leslie's army, which had strong ideological ties to the radical Kirk Party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parlia ...

, was destroyed, losing over 14,000 men killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Cromwell's army then took Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and by the end of the year his army had occupied much of southern Scotland.

This military disaster discredited the radical Covenanters known as the

This military disaster discredited the radical Covenanters known as the Kirk Party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parlia ...

and caused the Covenanters and Scottish Royalists to bury their differences (at least temporarily) to try to repel the English Parliamentarian invasion of Scotland. The Scottish Parliament passed the Act of Levy in December 1650, requiring every burgh and shire to raise a quota of soldiers. A new round of conscription was undertaken, both in the Highlands and the Lowlands, to form a truly national army named the Army of the Kingdom, that was put under the command of Charles II himself. Although this was actually the largest force put into the field by the Scots during the Wars, it was badly trained and its morale was low as many of its constituent Royalist and Covenanter parts had until recently been killing each other.

In July 1651, under the command of General John Lambert, part of Cromwell's force crossed the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

into Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing

The Battle of Inverkeithing was fought on 20 July 1651 between an English army under John Lambert and a Scottish army led by James Holborne as part of an English invasion of Scotland. The battle was fought near the isthmus of the Ferry Pe ...

. The New Model Army advanced towards the royal base at Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

. In danger of being outflanked, Charles ordered his army south into England in a desperate last-ditch attempt to evade Cromwell and spark a Royalist uprising there. Cromwell followed Charles into England leaving George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

to finish the campaign in Scotland. Meanwhile, Monck took Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

on 14 August and Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

on 1 September, reportedly killing up to 2,000 of its 12,000 population and destroying every ship in the city's harbour, 60 in total.

The Scottish Army of the Kingdom marched towards the west of England because it was in that area that English Royalist sympathies were strongest. However, although some English Royalists joined the army, they came in far fewer numbers than Charles and his Scottish supporters had hoped. Cromwell finally engaged the new king at Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

on 3 September 1651, and beat him – in the process all but wiping out his army, killing 3,000 and taking 10,000 prisoners. Many of the Scottish prisoners taken by Cromwell were sold into indentured labour in the West Indies, Virginia and Berwick, Maine

Berwick is a town in York County, Maine, United States, situated in the southern part of the state beside the Salmon Falls River.

Today's South Berwick was set off from Berwick in 1814, North Berwick in 1831.

The population was 7,950 at th ...

. This defeat marked the real end of the Scottish war effort. Charles escaped to the European continent and with his flight, the Covenanters' hopes for political independence from the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

were dashed.

From occupation to restoration

Between 1651 and 1654 a royalist rising took place in Scotland.

Between 1651 and 1654 a royalist rising took place in Scotland. Dunnottar Castle

Dunnottar Castle ( gd, Dùn Fhoithear, "fort on the shelving slope") is a ruined medieval fortress located upon a rocky headland on the north-eastern coast of Scotland, about south of Stonehaven. The surviving buildings are largely of the 1 ...

was the last stronghold to fall to the English Parliament's troops in May 1652. Under the terms of the Tender of Union

The Tender of Union was a declaration of the Parliament of England during the Interregnum following the War of the Three Kingdoms stating that Scotland would cease to have an independent parliament and would join England in its emerging Commonwe ...

, the Scots were given 30 seats in a united Parliament in London, with General Monck appointed as the military governor of Scotland. During the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

was kept under the military occupation of an English army under George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

. Sporadic Royalist rebellions continued throughout the Commonwealth period in Scotland, particularly in western Highlands, where Alasdair MacColla

Alasdair Mac Colla Chiotaich MacDhòmhnaill (c. 1610 – 13 November 1647), also known by the English variant of his name Sir Alexander MacDonald, was a military officer best known for his participation in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, notably ...

had raised his forces in the 1640s. The northwest Highlands was the scene of another pro-royalist uprising in 1653–55, which was only put down with the deployment of 6,000 English troops there. Monck garrisoned forts all over the Highlands – for example at Inverness

Inverness (; from the gd, Inbhir Nis , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness"; sco, Innerness) is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands. Histori ...

, and finally put an end to Royalist resistance when he began deporting prisoners to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

as indentured labour

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

ers. However, lawlessness remained a problem, with bandits known as mosstroopers

Moss-troopers were brigands of the mid-17th century, who operated across the border country between Scotland and the northern English counties of Northumberland and Cumberland during the period of the English Commonwealth, until after the Restor ...

, very often former Royalist or Covenanter soldiers, plundering both the English troops and the civilian population.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, the factions and divisions which had struggled for supremacy during the early years of the interregnum reemerged. Monck, who had served Cromwell and the English Parliament throughout the civil wars, judged that his best interests and those of his country lay in the Restoration of Charles II. In 1660, he marched his troops south from Scotland to ensure the monarchy's reinstatement. Scotland's Parliament and legislative autonomy were restored under The Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

though many issues that had led to the wars; religion, Scotland's form of government and the status of the Highlands, remained unresolved. After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, many more Scots would die over the same disputes in Jacobite rebellions

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

.

The cost

It is estimated that roughly 28,000 men were killed in combat in Scotland itself during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. More soldiers usually died of disease than in action at this time (the ratio was often 3–1), so it is reasonable to speculate that the true military death toll is higher than this figure. In addition, it is estimated that around 15,000 civilians died as a direct result of the war – either through massacres or by disease. More indirectly, another 30,000 people died of theplague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

in Scotland between 1645 and 1649, a disease that was partly spread by the movement of armies throughout the country. If we also take into account the thousands of Scottish troops who died in the civil wars in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

(another 20,000 soldiers at least), the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

certainly represent one of the bloodiest episodes in Scottish history.

Timeline

Scottish factions

Labels applied to the various Scottish factions differ among sources. This timeline labels factions as follows. Bold cell entries indicate the faction in control of the Scottish government during most of that period.Timeline of Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

See also

*Chronology of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Chronology of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms lists major events that occurred during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The presentation of the data in a table format allows interested parties to copy and transfer the data to other software or da ...

* History of Scotland

The recorded begins with the arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. North of this was Caledonia, inhabited by the ''Picti'', whose uprisings forced Rom ...

* Timeline of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

This is a timeline of events leading up to, culminating in, and resulting from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

1620s

1625

* 27 March: After the death of his father, King James VI and I, King Charles I accedes to the throne.

* 13 June: Charles ...

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *Stewart, Laura. 2019. Rethinking the Scottish Revolution: Covenanted Scotland, 1637–1651. Oxford University Press. {{Early Modern ScotlandExternal links

The Campaigns of 1644–45

Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Europe Civil wars of the Early Modern period Wars involving Scotland Wars of the Three Kingdoms 17th-century military history of Scotland