Scientific Revolutions (Ian Hacking) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of

The philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution were laid out by Francis Bacon, who has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the ''

The philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution were laid out by Francis Bacon, who has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the ''

''De Magnete'' was influential because of the inherent interest of its subject matter as well as for the rigorous way in which Gilbert describes his experiments and his rejection of ancient theories of magnetism. According to Thomas Thomson, "Gilbert s.. book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the ''Novum Organum'' of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained."

Galileo Galilei has been called the "father of modern

''De Magnete'' was influential because of the inherent interest of its subject matter as well as for the rigorous way in which Gilbert describes his experiments and his rejection of ancient theories of magnetism. According to Thomas Thomson, "Gilbert s.. book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the ''Novum Organum'' of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained."

Galileo Galilei has been called the "father of modern

The first moves towards the institutionalization of scientific investigation and dissemination took the form of the establishment of societies, where new discoveries were aired, discussed, and published. The first scientific society to be established was the

The first moves towards the institutionalization of scientific investigation and dissemination took the form of the establishment of societies, where new discoveries were aired, discussed, and published. The first scientific society to be established was the

Copernicus' 1543 work on the heliocentric model of the

Copernicus' 1543 work on the heliocentric model of the

Newton also developed the theory of gravitation. In 1679, Newton began to consider gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions. Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–81, on which he corresponded with

Newton also developed the theory of gravitation. In 1679, Newton began to consider gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions. Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–81, on which he corresponded with

The writings of Greek physician

The writings of Greek physician

William Gilbert, in ''De Magnete'', invented the

William Gilbert, in ''De Magnete'', invented the

The Encyclopedia Americana; a library of universal knowledge, vol. X, pp. 172ff

(1918). New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp. By investigating the forces on a light metallic needle, balanced on a point, he extended the list of electric bodies and found that many substances, including metals and natural magnets, showed no attractive forces when rubbed. He noticed that dry weather with north or east wind was the most favourable atmospheric condition for exhibiting electric phenomena—an observation liable to misconception until the difference between

''Isaac Newton: adventurer in thought''

. p. 67 50 years later, Hadley developed ways to make precision aspheric and parabolic

The invention of the

The invention of the

The idea that modern science took place as a kind of revolution has been debated among historians. A weakness of the idea of a scientific revolution is the lack of a systematic approach to the question of knowledge in the period comprehended between the 14th and 17th centuries, leading to misunderstandings on the value and role of modern authors. From this standpoint, the

The idea that modern science took place as a kind of revolution has been debated among historians. A weakness of the idea of a scientific revolution is the lack of a systematic approach to the question of knowledge in the period comprehended between the 14th and 17th centuries, leading to misunderstandings on the value and role of modern authors. From this standpoint, the

emergence

In philosophy, systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when a complex entity has properties or behaviors that its parts do not have on their own, and emerge only when they interact in a wider whole.

Emergence plays a central rol ...

of modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

during the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, when developments in mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

(including human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

) and chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

transformed the views of society about nature.Galilei, Galileo (1974) ''Two New Sciences'', trans. Stillman Drake

Stillman Drake (December 24, 1910 – October 6, 1993), an American historian of science who moved to Canada in 1967 and acquired Canadian citizenship a few years later, is best known for his work on Galileo Galilei (1569–1642).

Including his ...

, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr. pp. 217, 225, 296–67.Clagett, Marshall (1961) ''The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages''. Madison, Univ. of Wisconsin Pr. pp. 218–19, 252–55, 346, 409–16, 547, 576–78, 673–82 Hannam, p. 342 The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe in the second half of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

period, with the 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

publication ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') often cited as its beginning. The Scientific Revolution has been called "the most important transformation in human history" since the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

.

The era of the Scientific Renaissance focused to some degree on recovering the knowledge of the ancients and is considered to have culminated in Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

's 1687 publication '' Principia'' which formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

, thereby completing the synthesis of a new cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

. The subsequent Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

saw the concept of a scientific revolution emerge in the 18th-century work of Jean Sylvain Bailly

Jean Sylvain Bailly (; 15 September 1736 – 12 November 1793) was a French astronomer, mathematician, freemason, and political leader of the early part of the French Revolution. He presided over the Tennis Court Oath, served as the mayor of ...

, who described a two-stage process of sweeping away the old and establishing the new. There continues to be scholarly engagement regarding the boundaries of the Scientific Revolution and its chronology.

Introduction

Great advances in science have been termed "revolutions" since the 18th century. For example, in 1747, the French mathematicianAlexis Clairaut

Alexis Claude Clairaut (; ; 13 May 1713 – 17 May 1765) was a French mathematician, astronomer, and geophysicist. He was a prominent Newtonian whose work helped to establish the validity of the principles and results that Isaac Newton, Sir Isaa ...

wrote that " Newton was said in his own life to have created a revolution". The word was also used in the preface to Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that i ...

's 1789 work announcing the discovery of oxygen. "Few revolutions in science have immediately excited so much general notice as the introduction of the theory of oxygen ... Lavoisier saw his theory accepted by all the most eminent men of his time, and established over a great part of Europe within a few years from its first promulgation."

In the 19th century, William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

described the revolution in science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

itself – the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

– that had taken place in the 15th–16th century. "Among the most conspicuous of the revolutions which opinions on this subject have undergone, is the transition from an implicit trust in the internal powers of man's mind to a professed dependence upon external observation; and from an unbounded reverence for the wisdom of the past, to a fervid expectation of change and improvement." This gave rise to the common view of the Scientific Revolution today:

The Scientific Revolution is traditionally assumed to start with the Copernican Revolution

The term "Copernican Revolution" was coined by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in his 1781 work ''Critique of Pure Reason''. It was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth sta ...

(initiated in 1543) and to be complete in the "grand synthesis" of Isaac Newton's 1687 '' Principia''. Much of the change of attitude came from Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

whose "confident and emphatic announcement" in the modern progress of science inspired the creation of scientific societies such as the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

who championed Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

and developed the science of motion.

The Scientific Revolution was enabled by advances in book production. Before the advent of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

, introduced in Europe in the 1440s by Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg ( – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and Artisan, craftsman who invented the movable type, movable-type printing press. Though movable type was already in use in East Asia, Gutenberg's inven ...

, there was no mass market on the continent for scientific treatises, as there had been for religious books. Printing decisively changed the way scientific knowledge was created, as well as how it was disseminated. It enabled accurate diagrams, maps, anatomical drawings, and representations of flora and fauna to be reproduced, and printing made scholarly books more widely accessible, allowing researchers to consult ancient texts freely and to compare their own observations with those of fellow scholars.Martyn Lyons, ''Books: A Living History''. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011, 71. Although printers' blunders still often resulted in the spread of false data (for instance, in Galileo's ''Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in Neo-Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first published ...

'' (The Starry Messenger), published in Venice in 1610, his telescopic images of the lunar surface mistakenly appeared back to front), the development of engraved metal plates allowed accurate visual information to be made permanent, a change from previously, when woodcut illustrations deteriorated through repetitive use. The ability to access previous scientific research meant that researchers did not have to always start from scratch in making sense of their own observational data.

In the 20th century, Alexandre Koyré

Alexandre Koyré (; ; born Alexandr Vladimirovich (or Volfovich) Koyra; 29 August 1892 – 28 April 1964), also anglicized as Alexander Koyre, was a French philosopher of Russian origin who wrote on the history and philosophy of science. ...

introduced the term "scientific revolution", centering his analysis on Galileo. The term was popularized by Herbert Butterfield

Sir Herbert Butterfield (7 October 1900 – 20 July 1979) was an English historian and philosopher of history, who was Regius Professor of Modern History and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He is remembered chiefly for a sh ...

in his ''Origins of Modern Science''. Thomas Kuhn

Thomas Samuel Kuhn (; July 18, 1922 – June 17, 1996) was an American History and philosophy of science, historian and philosopher of science whose 1962 book ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' was influential in both academic and ...

's 1962 work ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' is a 1962 book about the history of science by the philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn. Its publication was a landmark event in the History of science, history, Philosophy of science, philosophy, and sociology ...

'' emphasizes that different theoretical frameworks—such as Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

and Newton's theory of gravity

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the sq ...

, which it replaced—cannot be directly compared without meaning loss.

Significance

The period saw a fundamental transformation in scientific ideas across mathematics, physics, astronomy, and biology in institutions supporting scientific investigation and in the more widely held picture of the universe. The Scientific Revolution led to the establishment of several modern sciences. In 1984, Joseph Ben-David wrote: Many contemporary writers and modern historians claim that there was a revolutionary change in world view. In 1611 English poetJohn Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

wrote:

Butterfield was less disconcerted but nevertheless saw the change as fundamental:

Historian Peter Harrison attributes Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution:

Ancient and medieval background

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

learning and science in the Middle Ages, as it had been elaborated and further developed by Roman/Byzantine science and medieval Islamic science. Grant, pp. 29–30, 42–47. Some scholars have noted a direct tie between "particular aspects of traditional Christianity" and the rise of science. The " Aristotelian tradition" was still an important intellectual framework in the 17th century, although by that time natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

had moved away from much of it. Key scientific ideas dating back to classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

had changed drastically over the years and in many cases had been discredited. The ideas that remained, which were transformed fundamentally during the Scientific Revolution, include:

* Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's cosmology that placed the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

at the center of a spherical hierarchic cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

. The terrestrial and celestial regions were made up of different elements which had different kinds of ''natural movement''.

** The terrestrial region, according to Aristotle, consisted of concentric spheres of the four classical element

The classical elements typically refer to Earth (classical element), earth, Water (classical element), water, Air (classical element), air, Fire (classical element), fire, and (later) Aether (classical element), aether which were proposed to ...

s—earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

, air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

. All bodies naturally moved in straight lines until they reached the sphere appropriate to their elemental composition—their ''natural place''. All other terrestrial motions were non-natural, or ''violent''.

** The celestial region was made up of the fifth element, aether, which was unchanging and moved naturally with uniform circular motion. In the Aristotelian tradition, astronomical theories sought to explain the observed irregular motion of celestial objects through the combined effects of multiple uniform circular motions.

* The Ptolemaic model of planetary motion: based on the geometrical model of Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; , ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Ancient Greek astronomy, astronomer, Greek mathematics, mathematician, doctor, and lawmaker. He was a student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original work ...

, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

'', demonstrated that calculations could compute the exact positions of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets in the future and in the past, and showed how these computational models were derived from astronomical observations. As such they formed the model for later astronomical developments. The physical basis for Ptolemaic models invoked layers of spherical shells, though the most complex models were inconsistent with this physical explanation.

Ancient precedent existed for alternative theories and developments which prefigured later discoveries in the area of physics and mechanics; but in light of the limited number of works to survive translation in a period when many books were lost to warfare, such developments remained obscure for centuries and are traditionally held to have had little effect on the re-discovery of such phenomena; whereas the invention of the printing press made the wide dissemination of such incremental advances of knowledge commonplace. Meanwhile, however, significant progress in geometry, mathematics, and astronomy was made in medieval times.

It is also true that many of the important figures of the Scientific Revolution shared in the general Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

respect for ancient learning and cited ancient pedigrees for their innovations. Copernicus, Galileo, Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

and Newton all traced different ancient and medieval ancestries for the heliocentric system. In the Axioms Scholium of his ''Principia,'' Newton said its axiomatic three laws of motion were already accepted by mathematicians such as Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

, Wallace, Wren and others. While preparing a revised edition of his ''Principia'', Newton attributed his law of gravity and his first law of motion to a range of historical figures.

Despite these qualifications, the standard theory of the history of the Scientific Revolution claims that the 17th century was a period of revolutionary scientific changes. Not only were there revolutionary theoretical and experimental developments, but that even more importantly, the way in which scientists worked was radically changed. For instance, although intimations of the concept of inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

are suggested sporadically in ancient discussion of motion, the salient point is that Newton's theory differed from ancient understandings in key ways, such as an external force being a requirement for violent motion in Aristotle's theory.

Scientific method

Under thescientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

as conceived in the 17th century, natural and artificial circumstances were set aside as a research tradition of systematic experimentation was slowly accepted by the scientific community. The philosophy of using an inductive approach to obtain knowledge—to abandon assumption and to attempt to observe with an open mind—was in contrast with the earlier, Aristotelian approach of deduction, by which analysis of known facts produced further understanding. In practice, many scientists and philosophers believed that a healthy mix of both was needed—the willingness to question assumptions, yet also to interpret observations assumed to have some degree of validity.

By the end of the Scientific Revolution the qualitative world of book-reading philosophers had been changed into a mechanical, mathematical world to be known through experimental research. Though it is certainly not true that Newtonian science was like modern science in all respects, it conceptually resembled ours in many ways. Many of the hallmarks of modern science, especially with regard to its institutionalization and professionalization, did not become standard until the mid-19th century.

Empiricism

The Aristotelian scientific tradition's primary mode of interacting with the world was through observation and searching for "natural" circumstances through reasoning. Coupled with this approach was the belief that rare events which seemed to contradict theoretical models were aberrations, telling nothing about nature as it "naturally" was. During the Scientific Revolution, changing perceptions about the role of the scientist in respect to nature, the value of evidence, experimental or observed, led towards a scientific methodology in which empiricism played a large role. By the start of the Scientific Revolution, empiricism had already become an important component of science and natural philosophy. Prior thinkers, including the early-14th-centurynominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

philosopher William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

, had begun the intellectual movement toward empiricism. The term British empiricism came into use to describe philosophical differences perceived between two of its founders Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

, described as empiricist, and René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

, who was described as a rationalist. Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, George Berkeley

George Berkeley ( ; 12 March 168514 January 1753), known as Bishop Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne of the Anglican Church of Ireland), was an Anglo-Irish philosopher, writer, and clergyman who is regarded as the founder of "immaterialism", a philos ...

, and David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

were the philosophy's primary exponents who developed a sophisticated empirical tradition as the basis of human knowledge.

An influential formulation of empiricism was John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

's ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'' (1689), in which he maintained that the only true knowledge that could be accessible to the human mind was that which was based on experience. He wrote that the human mind was created as a ''tabula rasa

''Tabula rasa'' (; Latin for "blank slate") is the idea of individuals being born empty of any built-in mental content, so that all knowledge comes from later perceptions or sensory experiences. Proponents typically form the extreme "nurture" ...

'', a "blank tablet," upon which sensory impressions were recorded and built up knowledge through a process of reflection.

Bacon's contributions

The philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution were laid out by Francis Bacon, who has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the ''

The philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution were laid out by Francis Bacon, who has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the ''Baconian method

The Baconian method is the investigative method developed by Francis Bacon, one of the founders of modern science, and thus a first formulation of a modern scientific method. The method was put forward in Bacon's book ''Novum Organum'' (1620), or ...

'', or simply the scientific method. His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology

In its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods. However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method is a structured procedure for bri ...

today.

Bacon proposed a great reformation of all process of knowledge for the advancement of learning divine and human, which he called ''Instauratio Magna'' (The Great Instauration). For Bacon, this reformation would lead to a great advancement in science and a progeny of inventions that would relieve mankind's miseries and needs. His ''Novum Organum

The ''Novum Organum'', fully ''Novum Organum, sive Indicia Vera de Interpretatione Naturae'' ("New organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature") or ''Instaurationis Magnae, Pars II'' ("Part II of The Great Instauratio ...

'' was published in 1620, in which he argues man is "the minister and interpreter of nature," "knowledge and human power are synonymous," "effects are produced by the means of instruments and helps," "man while operating can only apply or withdraw natural bodies; nature internally performs the rest," and "nature can only be commanded by obeying her". Here is an abstract of the philosophy of this work, that by the knowledge of nature and the using of instruments, man can govern or direct the natural work of nature to produce definite results. Therefore, that man, by seeking knowledge of nature, can reach power over it—and thus reestablish the "Empire of Man over creation," which had been lost by the Fall together with man's original purity. In this way, he believed, would mankind be raised above conditions of helplessness, poverty and misery, while coming into a condition of peace, prosperity and security.

For this purpose of obtaining knowledge of and power over nature, Bacon outlined in this work a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism

A syllogism (, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

In its earliest form (defin ...

, developing his scientific method, consisting of procedures for isolating the formal cause of a phenomenon (heat, for example) through eliminative induction. For him, the philosopher should proceed through inductive reasoning from fact

A fact is a truth, true data, datum about one or more aspects of a circumstance. Standard reference works are often used to Fact-checking, check facts. Science, Scientific facts are verified by repeatable careful observation or measurement by ...

to axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

to physical law

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow) ...

. Before beginning this induction, though, the enquirer must free his or her mind from certain false notions or tendencies which distort the truth. In particular, he found that philosophy was too preoccupied with words, particularly discourse and debate, rather than actually observing the material world: "For while men believe their reason governs words, in fact, words turn back and reflect their power upon the understanding, and so render philosophy and science sophistical and inactive."

Bacon considered that it is of greatest importance to science not to keep doing intellectual discussions or seeking merely contemplative aims, but that it should work for the bettering of mankind's life by bringing forth new inventions, even stating "inventions are also, as it were, new creations and imitations of divine works". He explored the far-reaching and world-changing character of inventions, such as the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

, gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

and the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

. Despite his influence on scientific methodology, he rejected correct novel theories such as William Gilbert's magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, Copernicus's heliocentrism, and Kepler's laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler in 1609 (except the third law, which was fully published in 1619), describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. These laws replaced circular orbits and epicycles in ...

.

Scientific experimentation

Bacon first described theexperimental method

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

.

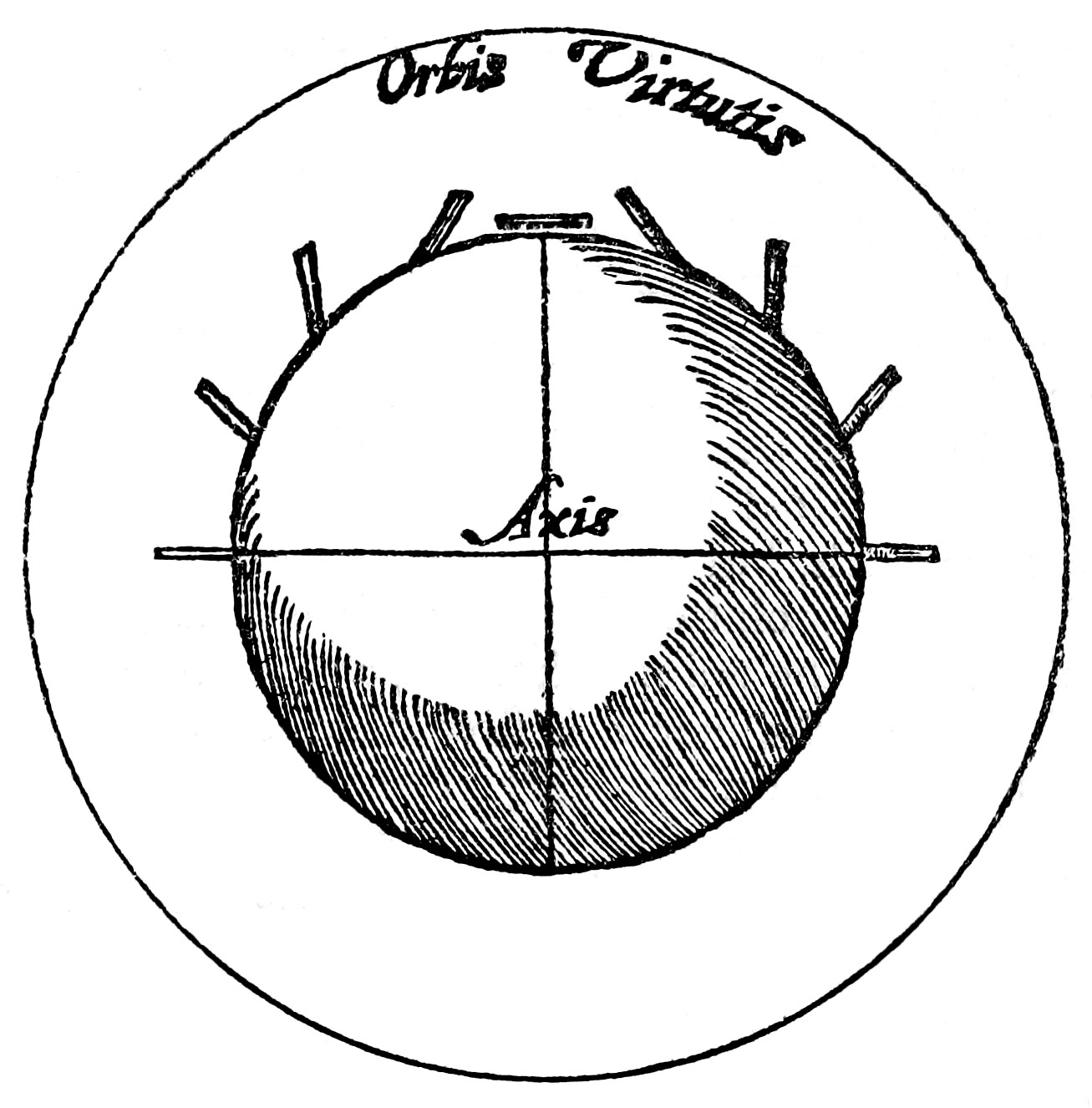

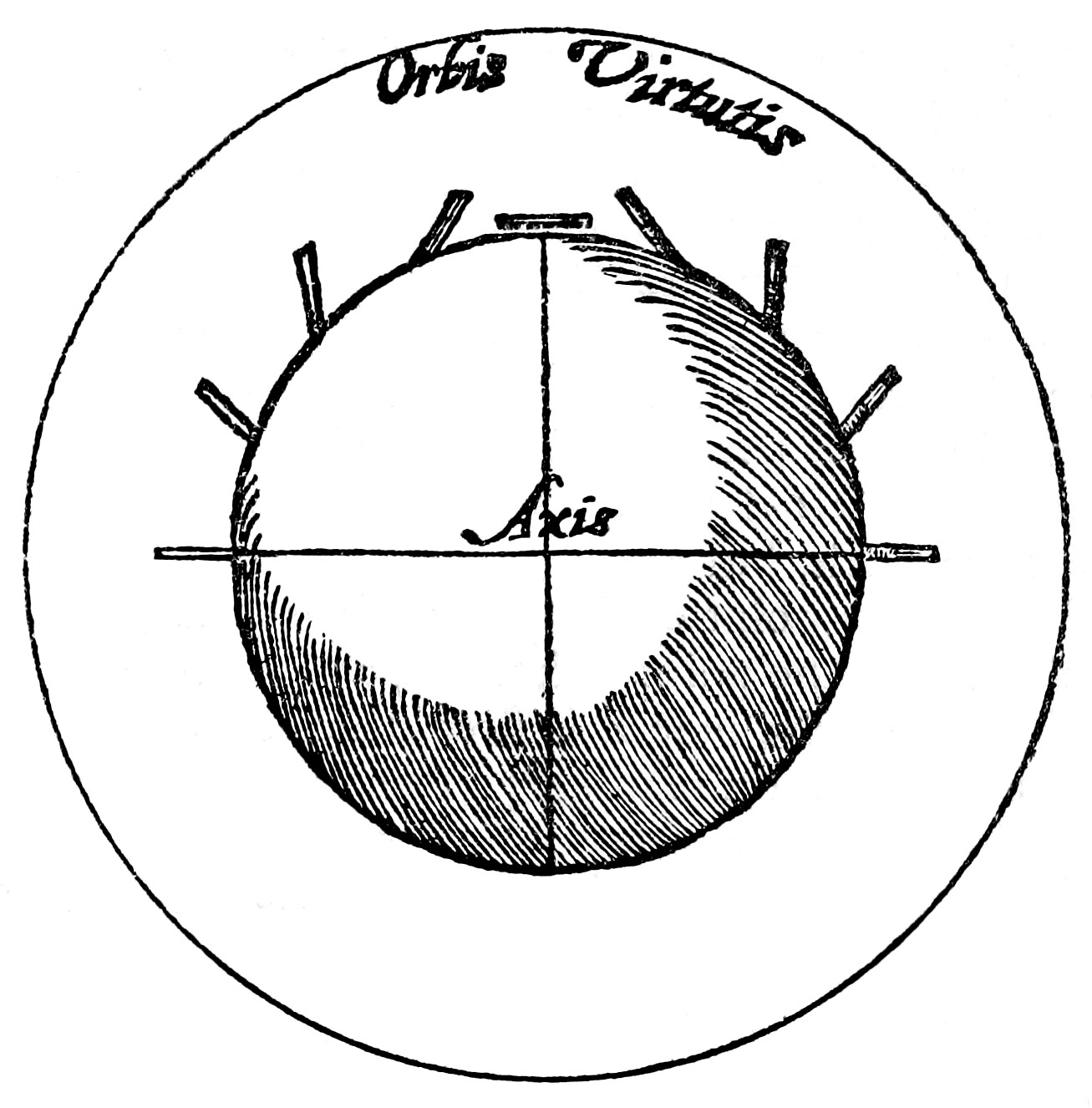

Gilbert was an early advocate of this method. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the scholastic method of university teaching. His book ''De Magnete

''De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure'' (''On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth'') is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert. A hi ...

'' was written in 1600, and he is regarded by some as the father of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and magnetism. In this work, he describes many of his experiments with his model Earth called the terrella

A terrella () is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientis ...

. From these experiments, he concluded that the Earth was itself magnetic and that this was the reason compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

es point north.

''De Magnete'' was influential because of the inherent interest of its subject matter as well as for the rigorous way in which Gilbert describes his experiments and his rejection of ancient theories of magnetism. According to Thomas Thomson, "Gilbert s.. book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the ''Novum Organum'' of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained."

Galileo Galilei has been called the "father of modern

''De Magnete'' was influential because of the inherent interest of its subject matter as well as for the rigorous way in which Gilbert describes his experiments and his rejection of ancient theories of magnetism. According to Thomas Thomson, "Gilbert s.. book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the ''Novum Organum'' of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained."

Galileo Galilei has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical ...

," the "father of modern physics," the "father of science," and "the Father of Modern Science." His original contributions to the science of motion were made through an innovative combination of experiment and mathematics. Galileo was one of the first modern thinkers to clearly state that the laws of nature are mathematical. In ''The Assayer

''The Assayer'' () is a book by Galileo Galilei, published in Rome in October 1623. It is generally considered to be one of the pioneering works of the scientific method, first broaching the idea that the book of nature is to be read with mathem ...

'' he wrote "Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe ... It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures;...." His mathematical analyses are a further development of a tradition employed by late scholastic natural philosophers, which Galileo learned when he studied philosophy. He ignored Aristotelianism. In broader terms, his work marked another step towards the eventual separation of science from both philosophy and religion; a major development in human thought. He was often willing to change his views in accordance with observation. In order to perform his experiments, Galileo had to set up standards of length and time, so that measurements made on different days and in different laboratories could be compared in a reproducible fashion. This provided a reliable foundation on which to confirm mathematical laws using inductive reasoning.

Galileo showed an appreciation for the relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics. He understood the parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is Reflection symmetry, mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different Mathematics, mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactl ...

, both in terms of conic section

A conic section, conic or a quadratic curve is a curve obtained from a cone's surface intersecting a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a special case of the ellipse, tho ...

s and in terms of the ordinate

In mathematics, the abscissa (; plural ''abscissae'' or ''abscissas'') and the ordinate are respectively the first and second coordinate of a point in a Cartesian coordinate system:

: abscissa \equiv x-axis (horizontal) coordinate

: ordinate \e ...

(y) varying as the square of the abscissa (x). Galilei further asserted that the parabola was the theoretically ideal trajectory

A trajectory or flight path is the path that an object with mass in motion follows through space as a function of time. In classical mechanics, a trajectory is defined by Hamiltonian mechanics via canonical coordinates; hence, a complete tra ...

of a uniformly accelerated projectile in the absence of friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

and other disturbances. He conceded that there are limits to the validity of this theory, noting on theoretical grounds that a projectile trajectory of a size comparable to that of the Earth could not possibly be a parabola, but he nevertheless maintained that for distances up to the range of the artillery of his day, the deviation of a projectile's trajectory from a parabola would be only very slight.

Mathematization

Scientific knowledge, according to the Aristotelians, was concerned with establishing true and necessary causes of things. To the extent that medieval natural philosophers used mathematical problems, they limited social studies to theoretical analyses of local speed and other aspects of life. The actual measurement of a physical quantity, and the comparison of that measurement to a value computed on the basis of theory, was largely limited to the mathematical disciplines of astronomy andoptics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

in Europe.McCluskey, Stephen C. (1998) ''Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe''. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr. pp. 180–84, 198–202.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, European scientists began increasingly applying quantitative measurements to the measurement of physical phenomena on the Earth. Galileo maintained strongly that mathematics provided a kind of necessary certainty that could be compared to God's: "...with regard to those few propositions

A proposition is a statement that can be either true or false. It is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields. Propositions are the object s denoted by declarative sentences; for example, "The sky ...

] which the human intellect does understand, I believe its knowledge equals the Divine in objective certainty..."

Galileo anticipates the concept of a systematic mathematical interpretation of the world in his book '' Il Saggiatore'':

In 1591 François Viète

François Viète (; 1540 – 23 February 1603), known in Latin as Franciscus Vieta, was a French people, French mathematician whose work on new algebra was an important step towards modern algebra, due to his innovative use of letters as par ...

published ''In Artem Analyticem Isagoge'', which gave the first symbolic notation of parameters in algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

. Newton's development of infinitesimal calculus

Calculus is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of ...

opened up new applications of the methods of mathematics to science. Newton taught that scientific theory should be coupled with rigorous experimentation, which became the keystone of modern science.

Mechanical philosophy

Aristotle recognized four kinds of causes, and where applicable, the most important of them is the "final cause". The final cause was the aim, goal, or purpose of some natural process or man-made thing. Until the Scientific Revolution, it was very natural to see such aims, such as a child's growth, for example, leading to a mature adult. Intelligence was assumed only in the purpose of man-made artifacts; it was not attributed to other animals or to nature. In "mechanical philosophy

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes (principally living things) are similar to complicated machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other.

The doctrine of mechanism in philosophy comes in two diff ...

" no field or action at a distance is permitted, particles or corpuscles of matter are fundamentally inert. Motion is caused by direct physical collision. Where natural substances had previously been understood organically, the mechanical philosophers viewed them as machines. As a result, Newton's theory seemed like some kind of throwback to "spooky action at a distance

Action at a distance is the concept in physics that an object's motion (physics), motion can be affected by another object without the two being in Contact mechanics, physical contact; that is, it is the concept of the non-local interaction of ob ...

". According to Thomas Kuhn, Newton and Descartes held the teleological principle that God conserved the amount of motion in the universe:

Gravity, interpreted as an innate attraction between every pair of particles of matter, was an occult quality in the same sense as the scholastics' "tendency to fall" had been.... By the mid eighteenth century that interpretation had been almost universally accepted, and the result was a genuine reversion (which is not the same as a retrogression) to a scholastic standard. Innate attractions and repulsions joined size, shape, position and motion as physically irreducible primary properties of matter.Newton had also specifically attributed the inherent power of inertia to matter, against the mechanist thesis that matter has no inherent powers. But whereas Newton vehemently denied gravity was an inherent power of matter, his collaborator

Roger Cotes

Roger Cotes (10 July 1682 – 5 June 1716) was an English mathematician, known for working closely with Isaac Newton by proofreading the second edition of his famous book, the '' Principia'', before publication. He also devised the quadrature ...

made gravity also an inherent power of matter, as set out in his famous preface to the ''Principia's'' 1713 second edition which he edited, and contradicted Newton. And it was Cotes's interpretation of gravity rather than Newton's that came to be accepted.

Institutionalization

The first moves towards the institutionalization of scientific investigation and dissemination took the form of the establishment of societies, where new discoveries were aired, discussed, and published. The first scientific society to be established was the

The first moves towards the institutionalization of scientific investigation and dissemination took the form of the establishment of societies, where new discoveries were aired, discussed, and published. The first scientific society to be established was the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of London. This grew out of an earlier group, centered around Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England that does not accept students or award degrees. It was founded in 1597 under the Will (law), will of Sir Thomas Gresham, ...

in the 1640s and 1650s. According to a history of the college:

The scientific network which centered on Gresham College played a crucial part in the meetings which led to the formation of the Royal Society.These physicians and natural philosophers were influenced by the "new science", as promoted by Bacon in his ''

New Atlantis

''New Atlantis'' is a utopian novel by Sir Francis Bacon, published posthumously in 1626. It appeared unheralded and tucked into the back of a longer work of natural history, ''Sylva Sylvarum'' (forest of materials). In ''New Atlantis'', Bac ...

'', from approximately 1645 onwards. A group known as ''The Philosophical Society of Oxford'' was run under a set of rules still retained by the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

.

On 28 November 1660, the "1660 committee of 12" announced the formation of a "College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning", which would meet weekly to discuss science and run experiments. At the second meeting, Robert Moray

Sir Robert Moray (alternative spellings: Murrey, Murray) FRS (1608 or 1609 – 4 July 1673) was a Scottish soldier, statesman, diplomat, judge, spy, and natural philosopher. He was well known to Charles I and Charles II, and to the French ...

announced that King Charles

King Charles may refer to:

Kings

A number of kings of Albania, Alençon, Anjou, Austria, Bohemia, Croatia, England, France, Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Ireland, Jerusalem, Naples, Navarre, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Sardinia, Scotland, Sicily, S ...

approved of the gatherings, and a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

was signed on 15 July 1662 creating the "Royal Society of London", with Lord Brouncker serving as the first president. A second royal charter was signed on 23 April 1663, with the king noted as the founder and with the name of "the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge"; Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

was appointed as curator of experiments in November. This initial royal favour has continued, and since then every monarch has been the patron of the society.

The society's first secretary was Henry Oldenburg

Henry Oldenburg (also Henry Oldenbourg) (c. 1618 as Heinrich Oldenburg – 5 September 1677) was a German theologian, diplomat, and natural philosopher, known as one of the creators of modern scientific peer review. He was one of the foremos ...

. Its early meetings included experiments performed first by Hooke and then by Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker, the steam engine, the centrifug ...

, who was appointed in 1684. These experiments varied in their subject area and were important in some cases and trivial in others.Henderson (1941) p. 29 The society began publication of ''Philosophical Transactions

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the second journ ...

'' from 1665, the oldest and longest-running scientific journal in the world, which established the important principles of scientific priority

In science, priority is the credit given to the individual or group of individuals who first made the discovery or proposed the theory. Fame and honours usually go to the first person or group to publish a new finding, even if several researchers a ...

and peer review

Peer review is the evaluation of work by one or more people with similar competencies as the producers of the work (:wiktionary:peer#Etymology 2, peers). It functions as a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the ...

.

The French established the Academy of Sciences in 1666. In contrast to the private origins of its British counterpart, the academy was founded as a government body by Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the countr ...

. Its rules were set down in 1699 by King Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, when it received the name of 'Royal Academy of Sciences' and was installed in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

in Paris.

New ideas

As the Scientific Revolution was not marked by any single change, the following new ideas contributed to what is called the Scientific Revolution. Many of them were revolutions in their own fields.Astronomy

Heliocentrism

For almost five millennia, thegeocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded scientific theories, superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric m ...

of the Earth as the center of the universe had been accepted by all but a few astronomers. In Aristotle's cosmology, Earth's central location was perhaps less significant than its identification as a realm of imperfection, inconstancy, irregularity, and change, as opposed to the "heavens" (Moon, Sun, planets, stars), which were regarded as perfect, permanent, unchangeable, and in religious thought, the realm of heavenly beings. The Earth was even composed of different material, the four elements "earth", "water", "fire", and "air", while sufficiently far above its surface (roughly the Moon's orbit), the heavens were composed of a different substance called "aether". The heliocentric model that replaced it involved the radical displacement of the Earth to an orbit around the Sun; sharing a placement with the other planets implied a universe of heavenly components made from the same changeable substances as the Earth. Heavenly motions no longer needed to be governed by a theoretical perfection, confined to circular orbits.

Copernicus' 1543 work on the heliocentric model of the

Copernicus' 1543 work on the heliocentric model of the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

tried to demonstrate that the Sun was the center of the universe. Few were bothered by this suggestion, and the pope and several archbishops were interested enough by it to want more detail. His model was later used to create the calendar of Pope Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII (, , born Ugo Boncompagni; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for commissioning and being the namesake ...

. However, the idea that the Earth moved around the Sun was doubted by most of Copernicus' contemporaries. It contradicted not only empirical observation, due to the absence of an observable stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the apparent shift of position (''parallax'') of any nearby star (or other object) against the background of distant stars. By extension, it is a method for determining the distance to the star through trigonometry, the stel ...

, but more significantly at the time, the authority of Aristotle. The discoveries of Kepler and Galileo gave the theory credibility.

Kepler was an astronomer who is best known for his laws of planetary motion, and Kepler´s books '' Astronomia nova'', ''Harmonice Mundi

''Harmonice Mundi'' (Latin: ''The Harmony of the World'', 1619) is a book by Johannes Kepler. In the work, written entirely in Latin, Kepler discusses harmony and congruence in geometrical forms and physical phenomena. The final section of t ...

'', and ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae

The ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' is an astronomy book on the heliocentric system published by Johannes Kepler in the period 1618 to 1621. The first volume (books I–III) was printed in 1618, the second (book IV) in 1620, and the third ...

'' influenced among others Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, providing one of the foundations for his theory of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

. One of the most significant books in the history of astronomy, the Astronomia nova provided strong arguments for heliocentrism and contributed valuable insight into the movement of the planets. This included the first mention of the planets' elliptical paths and the change of their movement to the movement of free floating bodies as opposed to objects on rotating spheres. It is recognized as one of the most important works of the Scientific Revolution. Using the accurate observations of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

, Kepler proposed that the planets move around the Sun not in circular orbits but in elliptical ones. Together with Kepler´s other laws of planetary motion, this allowed him to create a model of the Solar System that was an improvement over Copernicus' original system.

Galileo's main contributions to the acceptance of the heliocentric system were his mechanics, the observations he made with his telescope, as well as his detailed presentation of the case for the system. Using an early theory of inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

, Galileo could explain why rocks dropped from a tower fall straight down even if the Earth rotates. His observations of the moons of Jupiter

There are 97 Natural satellite, moons of Jupiter with confirmed orbits . This number does not include a number of meter-sized moonlets thought to be shed from the inner moons, nor hundreds of possible kilometer-sized outer irregular moons that ...

, the phases of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

, the spots on the Sun, and mountains on the Moon Mountains of the Moon may refer to:

* Mountains of the Moon (Africa), a legendary mountain range once thought to be the source of the Nile River in Uganda

* ''Mountains of the Moon'' (film), a 1990 film about a search for the source of the Nile

* ...

all helped to discredit the Aristotelian philosophy and the Ptolemaic theory of the Solar System. Through their combined discoveries, the heliocentric system gained support, and at the end of the 17th century it was generally accepted by astronomers.

This work culminated in the work of Newton, and his ''Principia'' formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation which dominated scientists' view of the physical universe for the next three centuries. By deriving Kepler's laws of planetary motion from his mathematical description of gravity, and then using the same principles to account for the trajectories of comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

s, the tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s, the precession of the equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun appears directly above the equator, rather than to its north or south. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise directly east and set directly west. This occurs twice each year, arou ...

es, and other phenomena, Newton removed the last doubts about the validity of the heliocentric model of the cosmos. This work also demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and of celestial bodies could be described by the same principles. His prediction that the Earth should be shaped as an oblate spheroid was later vindicated by other scientists. His laws of motion were to be the solid foundation of mechanics; his law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the s ...

combined terrestrial and celestial mechanics into one great system that seemed to be able to describe the whole world in mathematical formulae.

Gravitation

Newton also developed the theory of gravitation. In 1679, Newton began to consider gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions. Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–81, on which he corresponded with

Newton also developed the theory of gravitation. In 1679, Newton began to consider gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions. Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–81, on which he corresponded with John Flamsteed

John Flamsteed (19 August 1646 – 31 December 1719) was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, ''Catalogus Britannicus'', and a star atlas called '' Atlas ...

. After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force

Centripetal force (from Latin ''centrum'', "center" and ''petere'', "to seek") is the force that makes a body follow a curved trajectory, path. The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonality, orthogonal to the motion of the bod ...

inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. Newton communicated his results to Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

and to the Royal Society in ''De motu corporum in gyrum

(from Latin: "On the motion of bodies in an orbit"; abbreviated ) is the presumed title of a manuscript by Isaac Newton sent to Edmond Halley in November 1684. The manuscript was prompted by a visit from Halley earlier that year when he had qu ...

'' in 1684. This tract contained the nucleus that Newton developed and expanded to form the ''Principia''.

The ''Principia'' was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Halley. In this work, Newton states the three universal laws of motion that contributed to many advances during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

which soon followed and were not to be improved upon for more than 200 years. Many of these advancements continue to be the underpinnings of non-relativistic technologies in the modern world. He used the Latin word ''gravitas'' (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

and defined the law of universal gravitation.

Newton's postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances led to him being criticised for introducing "occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

agencies" into science. Later, in the second edition of the ''Principia'' (1713), Newton firmly rejected such criticisms in a concluding "General Scholium

The General Scholium () is an essay written by Isaac Newton, appended to his work of ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica'', known as the ''Principia''. It was first published with the second (1713) edition of the ''Principia'' and rea ...

," writing that it was enough that the phenomena implied a gravitational attraction, as they did; but they did not so far indicate its cause, and it was both unnecessary and improper to frame hypotheses of things that were not implied by the phenomena. (Here Newton used what became his famous expression "''hypotheses non fingo

In the history of physics, (Latin for "I frame no hypotheses", or "I contrive no hypotheses") is a phrase used by Isaac Newton in the essay , which was appended to the second edition of in 1713.

Original remark

A 1999 translation of the prese ...

''").

Biology and medicine

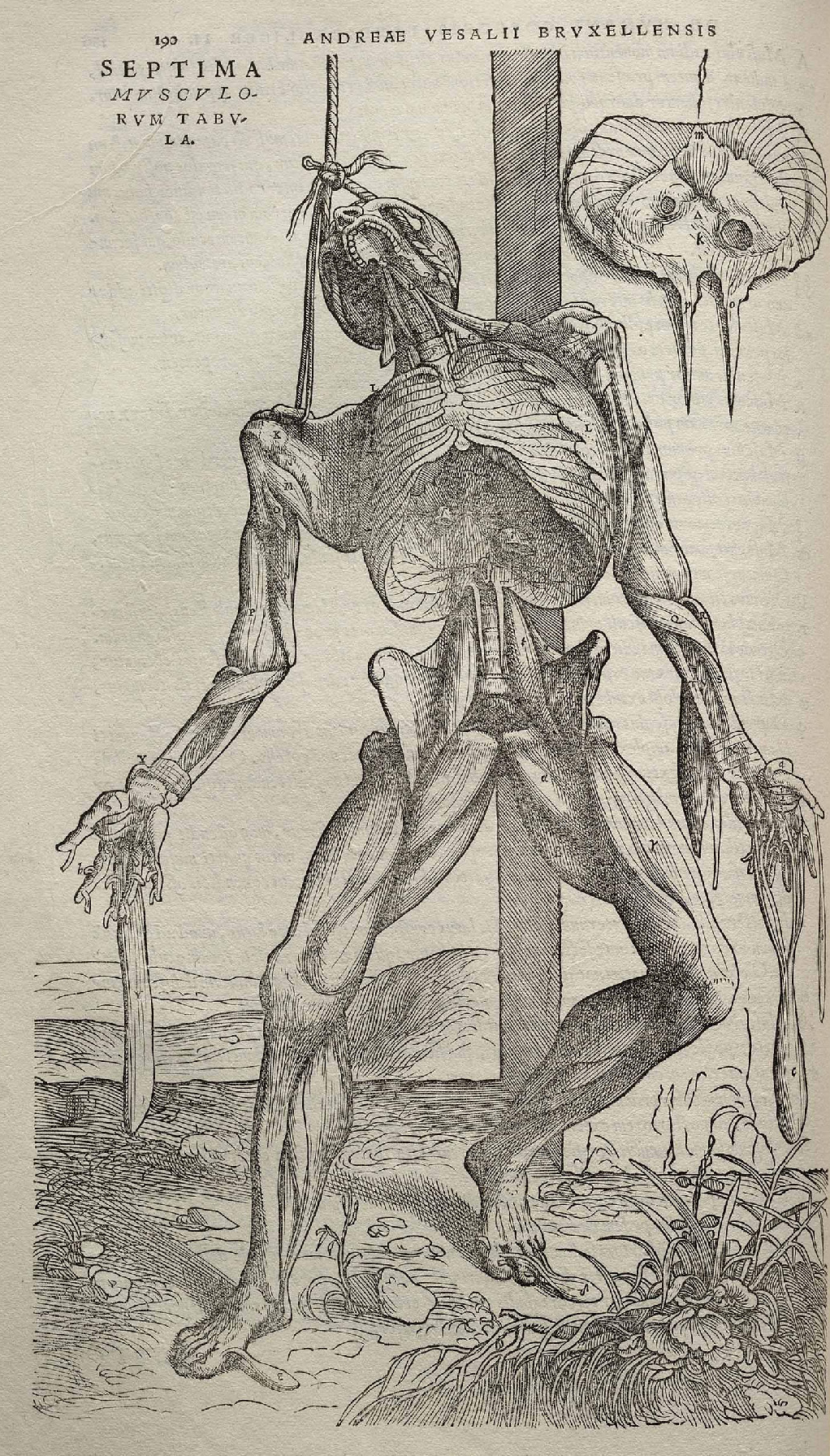

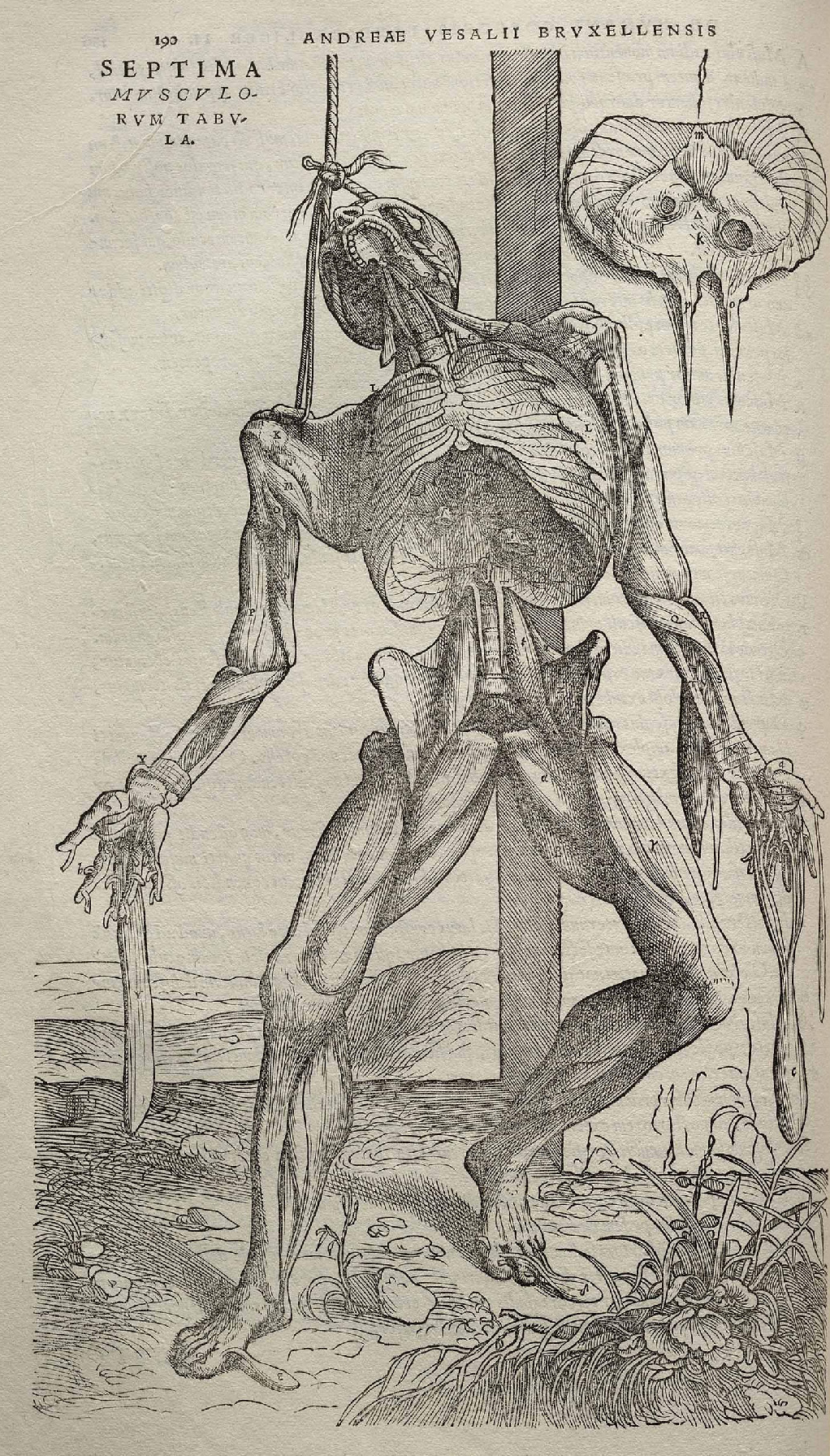

The writings of Greek physician

The writings of Greek physician Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

had dominated European medical thinking for over a millennium. The Flemish scholar Andreas Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote '' De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ''in seven books''), which is ...

demonstrated mistakes in Galen's ideas. Vesalius dissected human corpses, whereas Galen dissected animal corpses. Published in 1543, Vesalius' ''De humani corporis fabrica

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, "On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history of a ...

'' was a groundbreaking work of human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

. It emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously, which had strong Galenic/Aristotelean elements, as well as elements of astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

.

Besides the first good description of the sphenoid bone

The sphenoid bone is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of occipital bone, basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bon ...

, Vesalius showed that the sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

consists of three portions and the sacrum