Science Without Borders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes

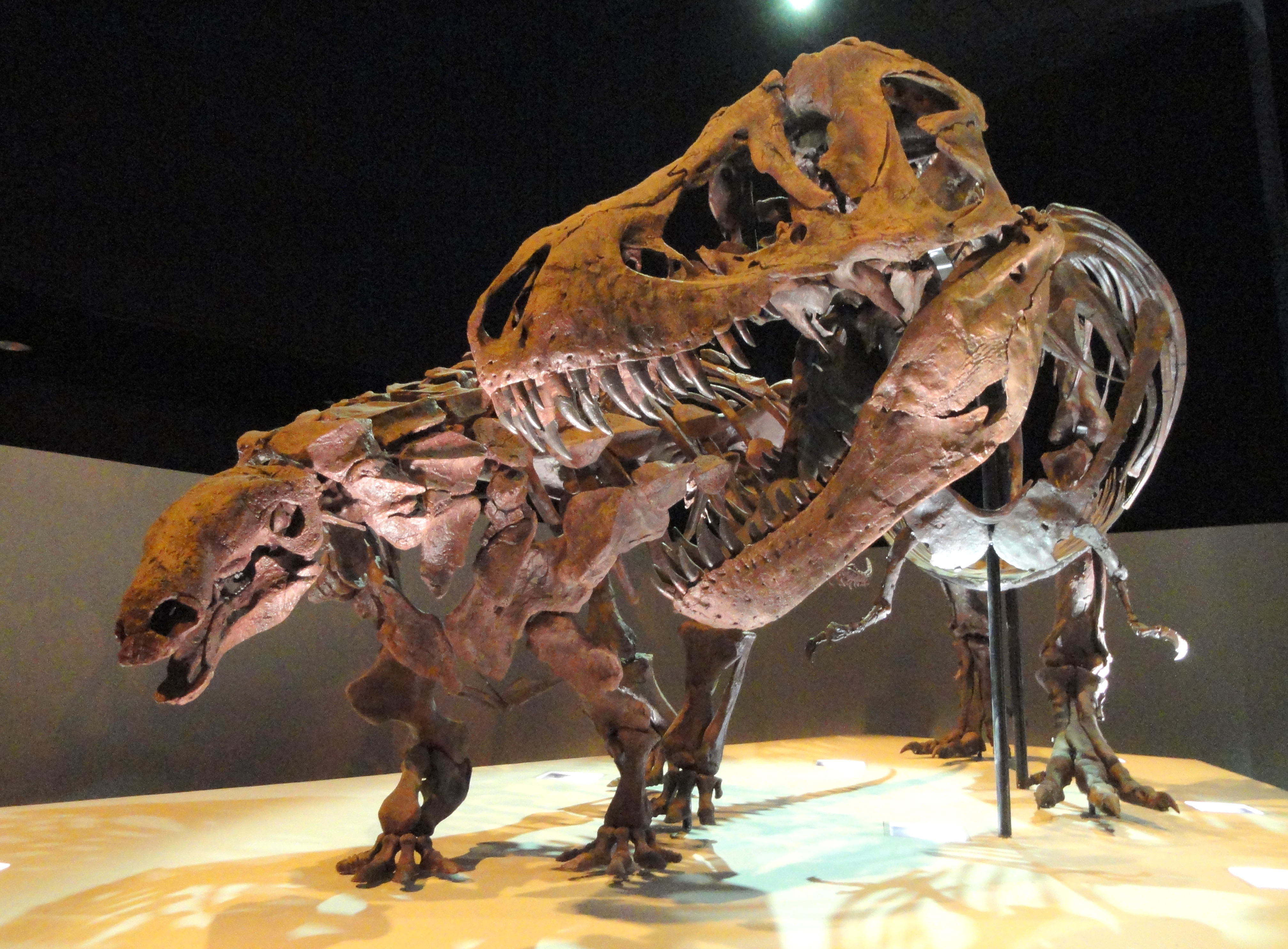

Science has no single origin. Rather, scientific methods emerged gradually over the course of thousands of years, taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Some of the earliest evidence for scientific reasoning is tens of thousands of years old, and

Science has no single origin. Rather, scientific methods emerged gradually over the course of thousands of years, taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Some of the earliest evidence for scientific reasoning is tens of thousands of years old, and

In

In

Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in

Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the

At the start of the

At the start of the

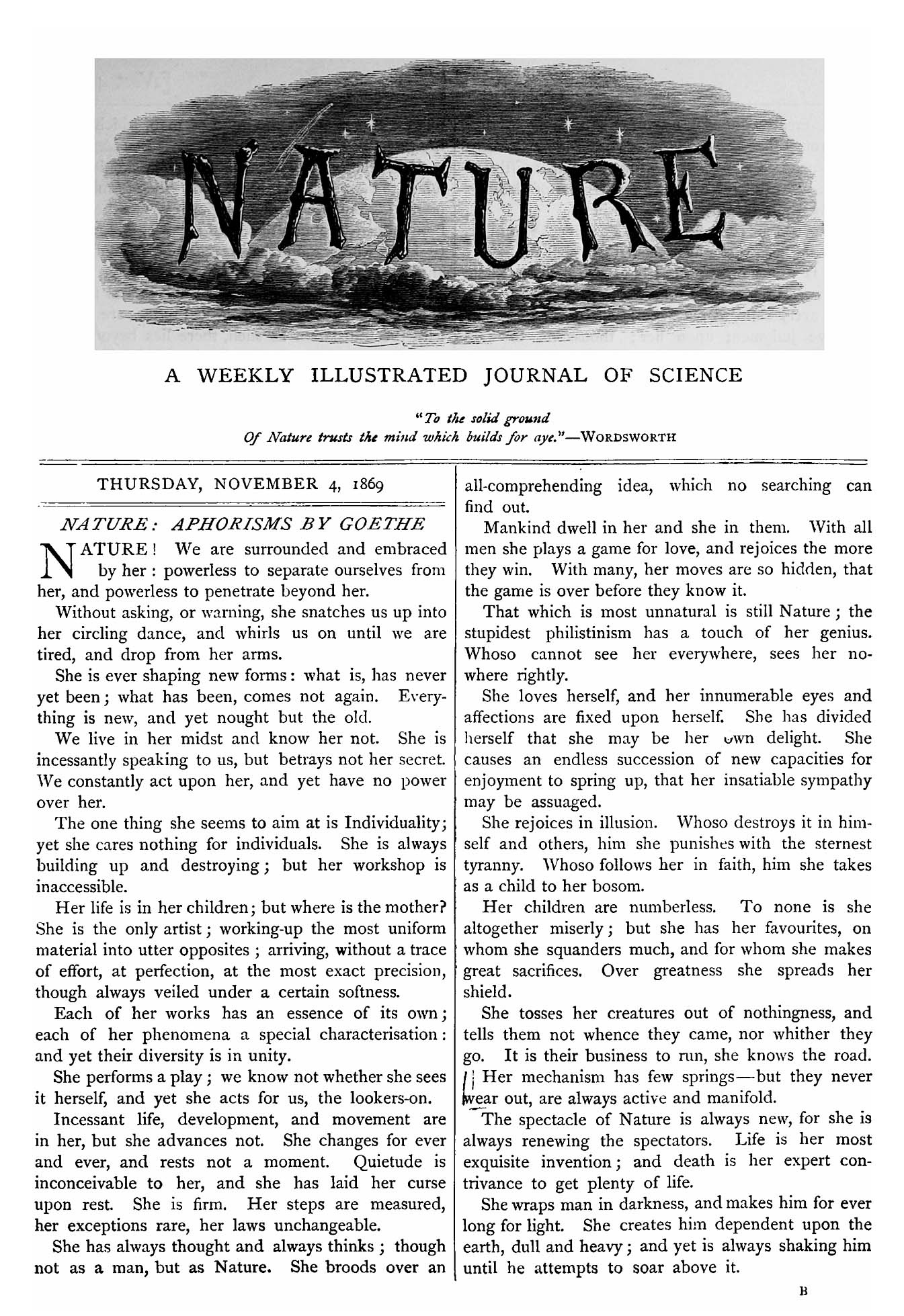

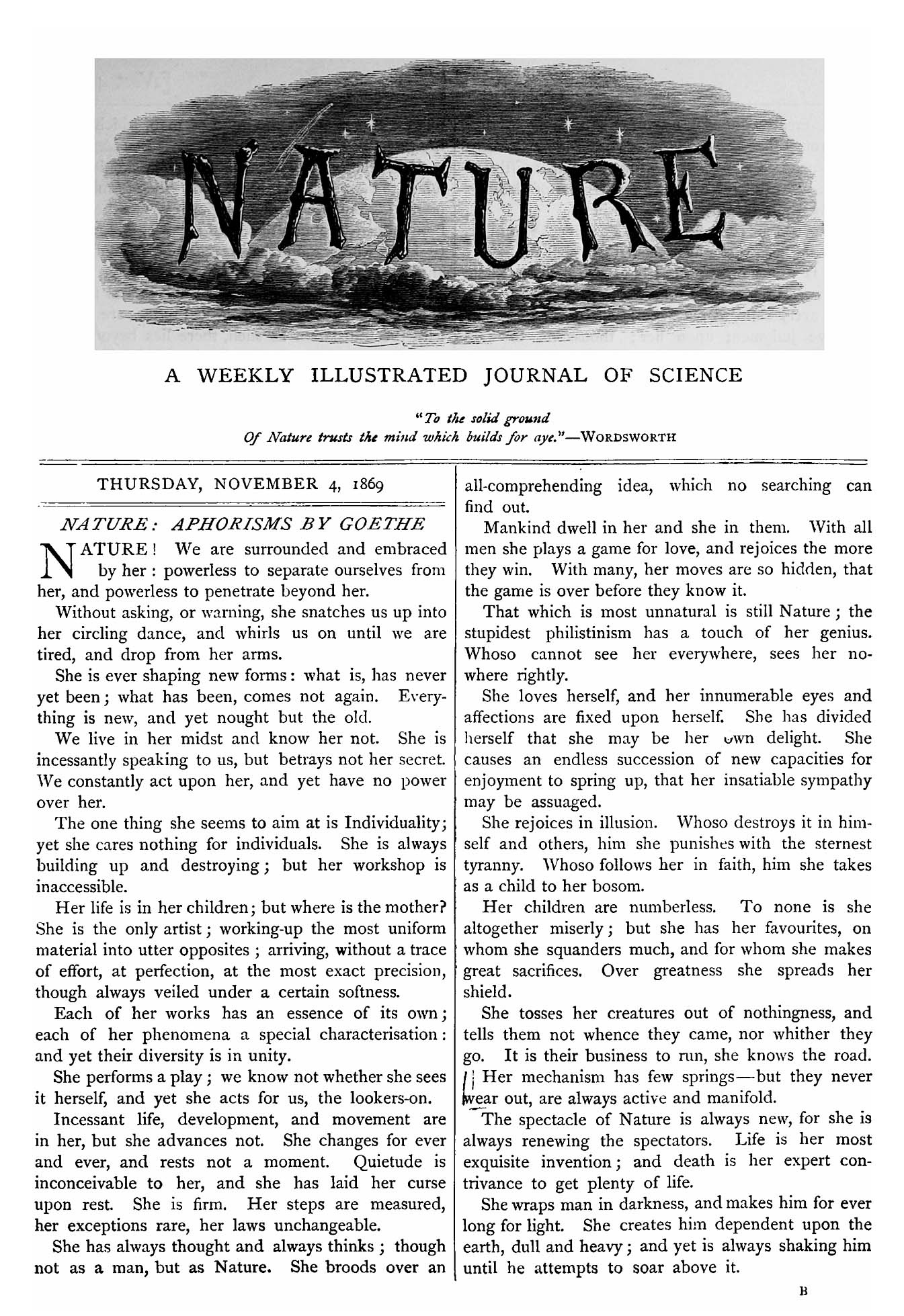

During the nineteenth century, many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences, frequent use of precision instruments, emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", "scientist", increased professionalization of those studying nature, scientists gained cultural authority over many dimensions of society, industrialization of numerous countries, thriving of popular science writings and emergence of science journals. During the late 19th century,

During the nineteenth century, many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences, frequent use of precision instruments, emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", "scientist", increased professionalization of those studying nature, scientists gained cultural authority over many dimensions of society, industrialization of numerous countries, thriving of popular science writings and emergence of science journals. During the late 19th century,

In the first half of the century, the development of

In the first half of the century, the development of

The

The

Scientific research involves using the

Scientific research involves using the

Scientific research is published in a range of literature. Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, ''Journal des sçavans'' followed by ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions'', began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.

Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a scientific paper. Science has become so pervasive in modern societies that it is considered necessary to communicate the achievements, news, and ambitions of scientists to a wider population.

Scientific research is published in a range of literature. Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, ''Journal des sçavans'' followed by ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions'', began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.

Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a scientific paper. Science has become so pervasive in modern societies that it is considered necessary to communicate the achievements, news, and ambitions of scientists to a wider population.

There are different schools of thought in the philosophy of science. The most popular position is empiricism, which holds that knowledge is created by a process involving observation; scientific theories generalize observations. Empiricism generally encompasses inductivism, a position that explains how general theories can be made from the finite amount of empirical evidence available. Many versions of empiricism exist, with the predominant ones being Bayesianism and the hypothetico-deductive method.

Empiricism has stood in contrast to rationalism, the position originally associated with Descartes, which holds that knowledge is created by the human intellect, not by observation. Critical rationalism is a contrasting 20th-century approach to science, first defined by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper. Popper rejected the way that empiricism describes the connection between theory and observation. He claimed that theories are not generated by observation, but that observation is made in the light of theories: that the only way theory A can be affected by observation is after theory A were to conflict with observation, but theory B were to survive the observation.

Popper proposed replacing verifiability with falsifiability as the landmark of scientific theories, replacing induction with Critical rationalism, falsification as the empirical method. Popper further claimed that there is actually only one universal method, not specific to science: the negative method of criticism, trial and error, covering all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, and art.

Another approach, instrumentalism, emphasizes the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena. It views scientific theories as black boxes with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be something that should be ignored. Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.

Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a paradigm, a logically consistent "portrait" of the world that is consistent with observations made from its framing. He characterized ''normal science'' as the process of observation and "puzzle solving" which takes place within a paradigm, whereas ''revolutionary science'' occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift. Each paradigm has its own distinct questions, aims, and interpretations. The choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. A paradigm shift occurs when a significant number of observational anomalies arise in the old paradigm and a new paradigm makes sense of them. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.

Finally, another approach often cited in debates of scientific skepticism against controversial movements like "creation science" is methodological naturalism. Naturalists maintain that a difference should be made between natural and supernatural, and science should be restricted to natural explanations. Methodological naturalism maintains that science requires strict adherence to empirical study and independent verification.

There are different schools of thought in the philosophy of science. The most popular position is empiricism, which holds that knowledge is created by a process involving observation; scientific theories generalize observations. Empiricism generally encompasses inductivism, a position that explains how general theories can be made from the finite amount of empirical evidence available. Many versions of empiricism exist, with the predominant ones being Bayesianism and the hypothetico-deductive method.

Empiricism has stood in contrast to rationalism, the position originally associated with Descartes, which holds that knowledge is created by the human intellect, not by observation. Critical rationalism is a contrasting 20th-century approach to science, first defined by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper. Popper rejected the way that empiricism describes the connection between theory and observation. He claimed that theories are not generated by observation, but that observation is made in the light of theories: that the only way theory A can be affected by observation is after theory A were to conflict with observation, but theory B were to survive the observation.

Popper proposed replacing verifiability with falsifiability as the landmark of scientific theories, replacing induction with Critical rationalism, falsification as the empirical method. Popper further claimed that there is actually only one universal method, not specific to science: the negative method of criticism, trial and error, covering all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, and art.

Another approach, instrumentalism, emphasizes the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena. It views scientific theories as black boxes with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be something that should be ignored. Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.

Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a paradigm, a logically consistent "portrait" of the world that is consistent with observations made from its framing. He characterized ''normal science'' as the process of observation and "puzzle solving" which takes place within a paradigm, whereas ''revolutionary science'' occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift. Each paradigm has its own distinct questions, aims, and interpretations. The choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. A paradigm shift occurs when a significant number of observational anomalies arise in the old paradigm and a new paradigm makes sense of them. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.

Finally, another approach often cited in debates of scientific skepticism against controversial movements like "creation science" is methodological naturalism. Naturalists maintain that a difference should be made between natural and supernatural, and science should be restricted to natural explanations. Methodological naturalism maintains that science requires strict adherence to empirical study and independent verification.

Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest. In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting and upon completion, attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy or PhD. Many scientists pursue careers in various Sector (economic), sectors of the economy such as Academy, academia, Private sector, industry, Administration (government), government, and nonprofit organizations.

Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality and a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, the environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. In modern times, many scientists have Terminal degree, advanced degrees in an area of science and pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as Academy, academia, Private industry, industry, Government scientist, government, and nonprofit environments.''''

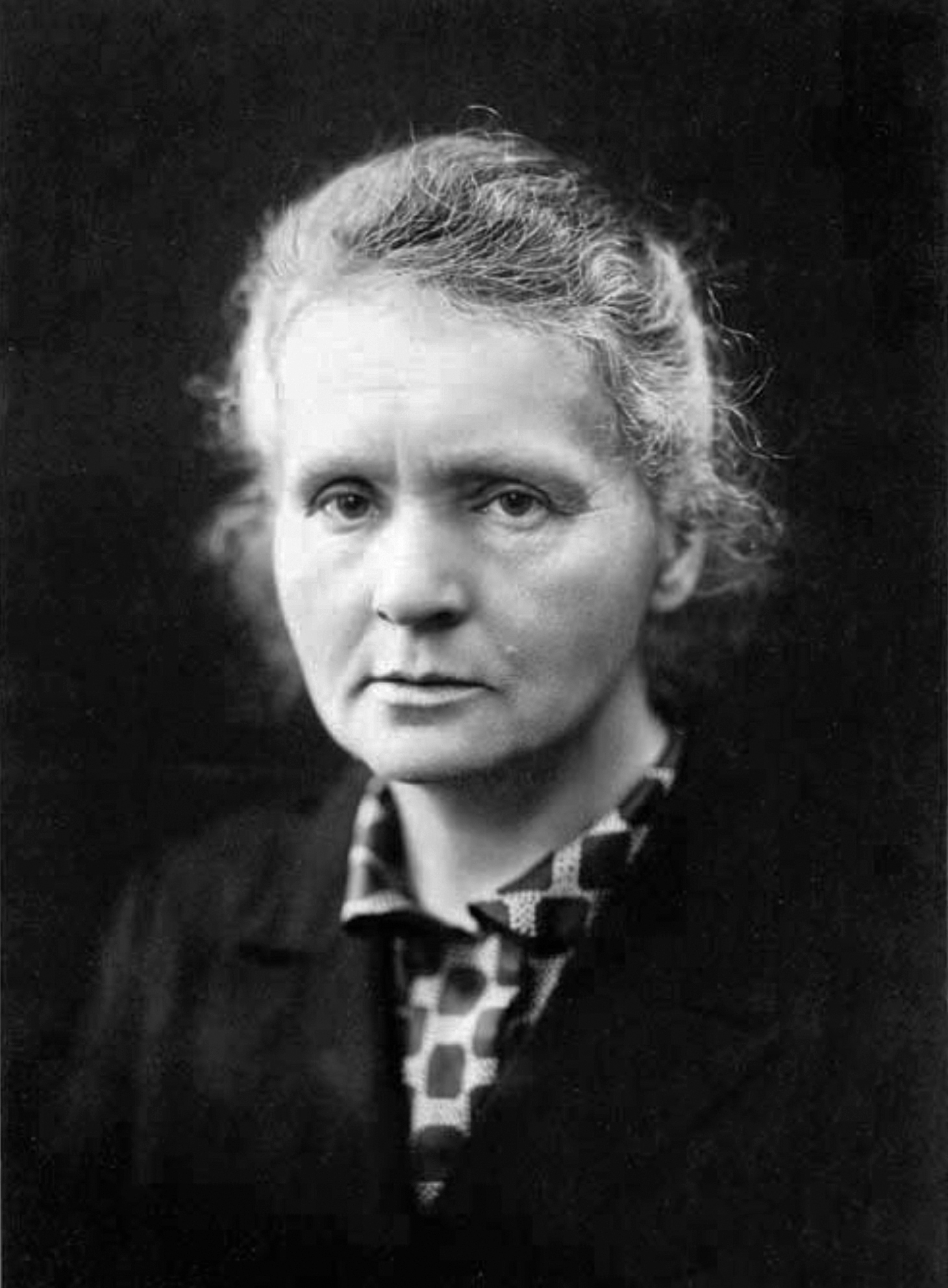

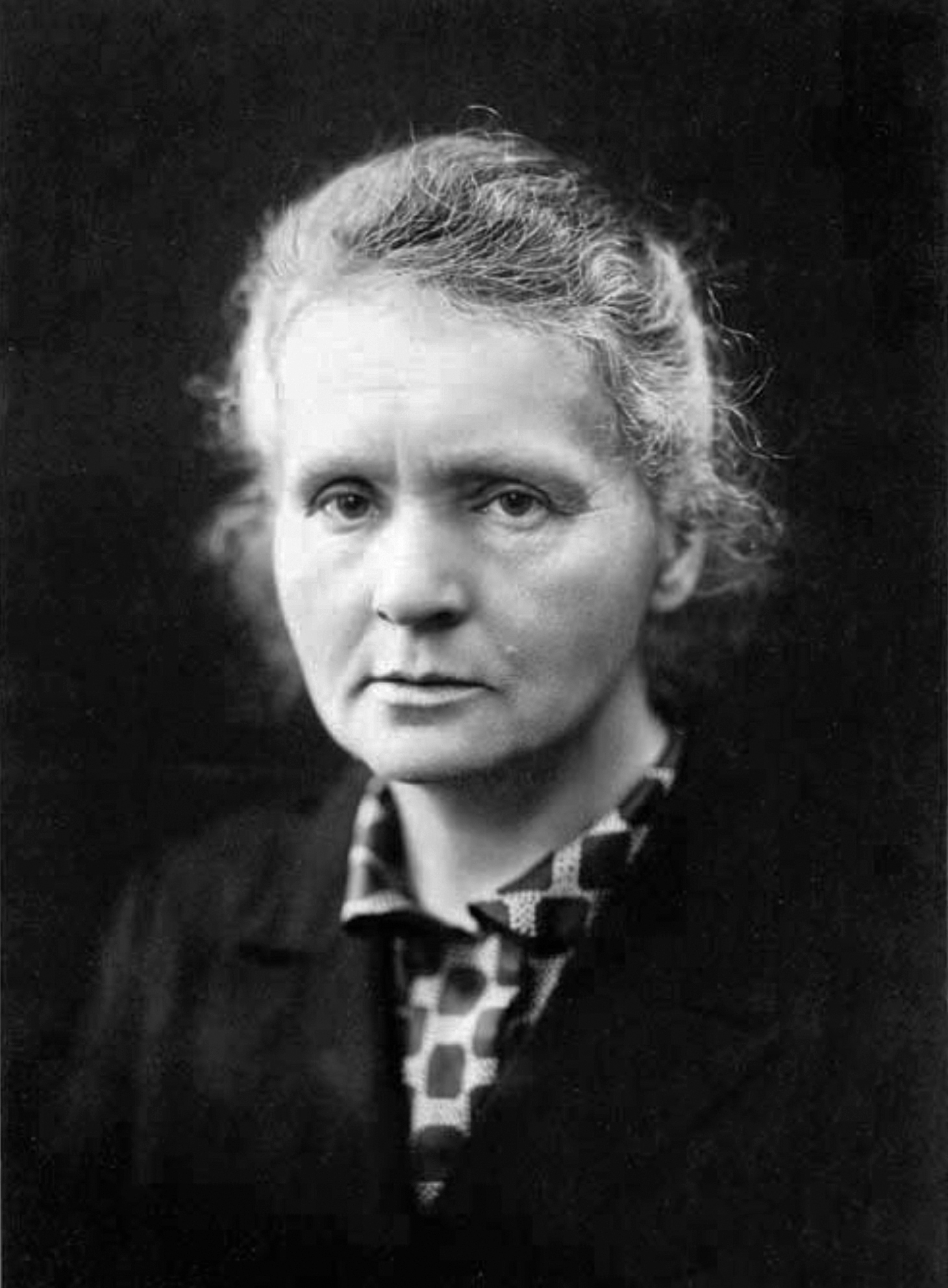

Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with notable exceptions. Women in science faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies. For example, women were frequently being passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work. The achievements of women in science have been attributed to the defiance of their traditional role as laborers within the Private sphere, domestic sphere. Lifestyle choice plays a major role in female engagement in science; female graduate students' interest in careers in research declines dramatically throughout graduate school, whereas that of their male colleagues remains unchanged.

Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest. In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting and upon completion, attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy or PhD. Many scientists pursue careers in various Sector (economic), sectors of the economy such as Academy, academia, Private sector, industry, Administration (government), government, and nonprofit organizations.

Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality and a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, the environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. In modern times, many scientists have Terminal degree, advanced degrees in an area of science and pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as Academy, academia, Private industry, industry, Government scientist, government, and nonprofit environments.''''

Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with notable exceptions. Women in science faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies. For example, women were frequently being passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work. The achievements of women in science have been attributed to the defiance of their traditional role as laborers within the Private sphere, domestic sphere. Lifestyle choice plays a major role in female engagement in science; female graduate students' interest in careers in research declines dramatically throughout graduate school, whereas that of their male colleagues remains unchanged.

Learned society, Learned societies for the communication and promotion of scientific thought and experimentation have existed since the Renaissance. Many scientists belong to a learned society that promotes their respective scientific discipline, profession, or group of related disciplines. Membership may either be open to all, require possession of scientific credentials, or conferred by election. Most scientific societies are non-profit organizations, and many are professional associations. Their activities typically include holding regular academic conference, conferences for the presentation and discussion of new research results and publishing or sponsoring academic journals in their discipline. Some societies act as professional bodies, regulating the activities of their members in the public interest or the collective interest of the membership.

The professionalization of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of national distinguished academy of sciences, academies of sciences such as the Italian in 1603, the British Royal Society in 1660, the French Academy of Sciences in 1666, the American National Academy of Sciences in 1863, the German Kaiser Wilhelm Society in 1911, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1949. International scientific organizations, such as the International Science Council, are devoted to international cooperation for science advancement.

Learned society, Learned societies for the communication and promotion of scientific thought and experimentation have existed since the Renaissance. Many scientists belong to a learned society that promotes their respective scientific discipline, profession, or group of related disciplines. Membership may either be open to all, require possession of scientific credentials, or conferred by election. Most scientific societies are non-profit organizations, and many are professional associations. Their activities typically include holding regular academic conference, conferences for the presentation and discussion of new research results and publishing or sponsoring academic journals in their discipline. Some societies act as professional bodies, regulating the activities of their members in the public interest or the collective interest of the membership.

The professionalization of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of national distinguished academy of sciences, academies of sciences such as the Italian in 1603, the British Royal Society in 1660, the French Academy of Sciences in 1666, the American National Academy of Sciences in 1863, the German Kaiser Wilhelm Society in 1911, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1949. International scientific organizations, such as the International Science Council, are devoted to international cooperation for science advancement.

Funding of science, Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed country, developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of Gross domestic product, GDP. In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10% respectively by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain fields is higher, and it dominates research in social science and humanities. In the lesser-developed nations, government provides the bulk of the funds for their basic scientific research.

Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research, such as the National Science Foundation in the United States, the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Argentina, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia, French National Centre for Scientific Research, National Centre for Scientific Research in France, the Max Planck Society in Germany, and Spanish National Research Council, National Research Council in Spain. In commercial research and development, all but the most research-oriented corporations focus more heavily on near-term commercialization possibilities rather than research driven by curiosity.

Science policy is concerned with policies that affect the conduct of the scientific enterprise, including research funding, often in pursuance of other national policy goals such as technological innovation to promote commercial product development, weapons development, health care, and environmental monitoring. Science policy sometimes refers to the act of applying scientific knowledge and consensus to the development of public policies. In accordance with public policy being concerned about the well-being of its citizens, science policy's goal is to consider how science and technology can best serve the public. Public policy can directly affect the funding of capital equipment and intellectual infrastructure for industrial research by providing tax incentives to those organizations that fund research.

Funding of science, Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed country, developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of Gross domestic product, GDP. In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10% respectively by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain fields is higher, and it dominates research in social science and humanities. In the lesser-developed nations, government provides the bulk of the funds for their basic scientific research.

Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research, such as the National Science Foundation in the United States, the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Argentina, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia, French National Centre for Scientific Research, National Centre for Scientific Research in France, the Max Planck Society in Germany, and Spanish National Research Council, National Research Council in Spain. In commercial research and development, all but the most research-oriented corporations focus more heavily on near-term commercialization possibilities rather than research driven by curiosity.

Science policy is concerned with policies that affect the conduct of the scientific enterprise, including research funding, often in pursuance of other national policy goals such as technological innovation to promote commercial product development, weapons development, health care, and environmental monitoring. Science policy sometimes refers to the act of applying scientific knowledge and consensus to the development of public policies. In accordance with public policy being concerned about the well-being of its citizens, science policy's goal is to consider how science and technology can best serve the public. Public policy can directly affect the funding of capital equipment and intellectual infrastructure for industrial research by providing tax incentives to those organizations that fund research.

Science education for the general public is embedded in the school curriculum, and is supplemented by YouTube in education, online pedagogical content (for example, YouTube and Khan Academy), museums, and science magazines and blogs. Scientific literacy is chiefly concerned with an understanding of the

Science education for the general public is embedded in the school curriculum, and is supplemented by YouTube in education, online pedagogical content (for example, YouTube and Khan Academy), museums, and science magazines and blogs. Scientific literacy is chiefly concerned with an understanding of the

Attitudes towards science are often determined by political opinions and goals. Government, business and advocacy groups have been known to use legal and economic pressure to influence scientific researchers. Many factors can act as facets of the politicization of science such as anti-intellectualism, perceived threats to religious beliefs, and fear for business interests. Politicization of science is usually accomplished when scientific information is presented in a way that emphasizes the uncertainty associated with the scientific evidence. Tactics such as shifting conversation, failing to acknowledge facts, and capitalizing on doubt of scientific consensus have been used to gain more attention for views that have been undermined by scientific evidence. Examples of issues that have involved the politicization of science include the global warming controversy, health effects of pesticides, and health effects of tobacco.

Attitudes towards science are often determined by political opinions and goals. Government, business and advocacy groups have been known to use legal and economic pressure to influence scientific researchers. Many factors can act as facets of the politicization of science such as anti-intellectualism, perceived threats to religious beliefs, and fear for business interests. Politicization of science is usually accomplished when scientific information is presented in a way that emphasizes the uncertainty associated with the scientific evidence. Tactics such as shifting conversation, failing to acknowledge facts, and capitalizing on doubt of scientific consensus have been used to gain more attention for views that have been undermined by scientific evidence. Examples of issues that have involved the politicization of science include the global warming controversy, health effects of pesticides, and health effects of tobacco.

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is distin ...

in the form of testable

Testability is a primary aspect of Science and the Scientific Method and is a property applying to an empirical hypothesis, involves two components:

#Falsifiability or defeasibility, which means that counterexamples to the hypothesis are logicall ...

explanation

An explanation is a set of statements usually constructed to describe a set of facts which clarifies the causes, context, and consequences of those facts. It may establish rules or laws, and may clarify the existing rules or laws in relatio ...

s and prediction

A prediction (Latin ''præ-'', "before," and ''dicere'', "to say"), or forecast, is a statement about a future event or data. They are often, but not always, based upon experience or knowledge. There is no universal agreement about the exact ...

s about the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

.

Science may be as old as the human species

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for scientific reasoning is tens of thousands of years old. The earliest written records in the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

come from Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

in around 3000 to 1200 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. Their contributions to mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acco ...

based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its va ...

, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, but was preserved in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

and later by the efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

.

The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived "natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

", which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transforme ...

that began in the 16th century as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century

The 19th (nineteenth) century began on 1 January 1801 ( MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 ( MCM). The 19th century was the ninth century of the 2nd millennium.

The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolish ...

that many of the institutional

Institutions are humanly devised structures of rules and norms that shape and constrain individual behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions a ...

and professional

A professional is a member of a profession or any person who works in a specified professional activity. The term also describes the standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the particular knowledge and sk ...

features of science began to take shape; along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".

Modern science is typically divided into three major branches: natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

s (e.g., biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

, and physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

), which study the physical world

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acco ...

; the social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of s ...

s (e.g., economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics anal ...

, psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

, and sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation an ...

), which study individual

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own need ...

s and societies

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societ ...

; and the formal sciences (e.g., logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and theoretical computer science

computer science (TCS) is a subset of general computer science and mathematics that focuses on mathematical aspects of computer science such as the theory of computation, lambda calculus, and type theory.

It is difficult to circumscribe the ...

), which study formal system

A formal system is an abstract structure used for inferring theorems from axioms according to a set of rules. These rules, which are used for carrying out the inference of theorems from axioms, are the logical calculus of the formal system.

A fo ...

s, governed by axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s and rules. There is disagreement whether the formal sciences are science disciplines, because they do not rely on empirical evidence

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences ...

. Applied science

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge obtained via conclusions from the method to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted ...

s are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as in engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

.

New knowledge in science is advanced by research

Research is "creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness ...

from scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosop ...

s who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems. Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

and research institutions

A research institute, research centre, research center or research organization, is an establishment founded for doing research. Research institutes may specialize in basic research or may be oriented to applied research. Although the term often im ...

, government agencies

A government or state agency, sometimes an appointed commission, is a permanent or semi-permanent organization in the machinery of government that is responsible for the oversight and administration of specific functions, such as an administratio ...

, and companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

. The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

, health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health pr ...

, public infrastructure

Public infrastructure is infrastructure owned or available for use by the public (represented by the government). It is distinguishable from generic or private infrastructure in terms of policy, financing, purpose, etc.

Public infrastructure is ...

, and environmental protection

Environmental protection is the practice of protecting the natural environment by individuals, organizations and governments. Its objectives are to conserve natural resources and the existing natural environment and, where possible, to repair dam ...

.

Etymology

The word ''science'' has been used inMiddle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old Englis ...

since the 14th century in the sense of "the state of knowing". The word was borrowed from the Anglo-Norman language

Anglo-Norman, also known as Anglo-Norman French ( nrf, Anglo-Normaund) (French: ), was a dialect of Old Norman French that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

When ...

as the suffix , which was borrowed from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

word , meaning "knowledge, awareness, understanding". It is a noun derivative of the Latin meaning "knowing", and undisputedly derived from the Latin , the present participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived fro ...

', meaning "to know".

There are many hypotheses for ''science''Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

linguist and Indo-Europeanist

Indo-European studies is a field of linguistics and an interdisciplinary field of study dealing with Indo-European languages, both current and extinct. The goal of those engaged in these studies is to amass information about the hypothetical pro ...

, may have its origin in the Proto-Italic language

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. P ...

as or meaning "to know", which may originate from Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

as '', '', meaning "to incise". The ''Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben

The ''Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben'' (''LIV'', ''"Lexicon of the Indo-European Verbs"'') is an etymological dictionary of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) verb. The first edition appeared in 1998, edited by Helmut Rix. A second edition foll ...

'' proposed is a back-formation

In etymology, back-formation is the process or result of creating a new word via inflection, typically by removing or substituting actual or supposed affixes from a lexical item, in a way that expands the number of lexemes associated with the ...

of , meaning "to not know, be unfamiliar with", which may derive from Proto-Indo-European ' in Latin , or ', from ' meaning "to cut".

In the past, science was a synonym for "knowledge" or "study", in keeping with its Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

origin. A person who conducted scientific research was called a "natural philosopher" or "man of science". In 1833, William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved ...

coined the term ''scientist'' and the term first appeared in literature one year later in Mary Somerville

Mary Somerville (; , formerly Greig; 26 December 1780 – 29 November 1872) was a Scottish scientist, writer, and polymath. She studied mathematics and astronomy, and in 1835 she and Caroline Herschel were elected as the first female Honorary ...

's '' On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences'', published in the '' Quarterly Review''.

History

Earliest roots

Science has no single origin. Rather, scientific methods emerged gradually over the course of thousands of years, taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Some of the earliest evidence for scientific reasoning is tens of thousands of years old, and

Science has no single origin. Rather, scientific methods emerged gradually over the course of thousands of years, taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Some of the earliest evidence for scientific reasoning is tens of thousands of years old, and women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

likely played a central role in prehistoric science, as did religious rituals. Some Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

authors have dismissed these efforts as " protoscientific".

Direct evidence for scientific processes becomes clearer with the advent of writing systems

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable f ...

in early civilizations like Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, creating the earliest written records in the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

in around 3000 to 1200 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. Although the words and concepts of "science" and "nature" were not part of the conceptual landscape at the time, the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians made contributions that would later find a place in Greek and medieval science: mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. From the 3rd millennium BCE, the ancient Egyptians developed a decimal numbering system, solved practical problems using geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, and developed a calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a phy ...

. Their healing therapies involved drug treatments and the supernatural, such as prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deifie ...

s, incantation

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremo ...

s, and rituals.

The ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

ns used knowledge about the properties of various natural chemicals for manufacturing pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

, faience

Faience or faïence (; ) is the general English language term for fine tin-glazed pottery. The invention of a white pottery glaze suitable for painted decoration, by the addition of an oxide of tin to the slip of a lead glaze, was a major ...

, glass, soap, metals, lime plaster

Lime plaster is a type of plaster composed of sand, water, and lime, usually non-hydraulic hydrated lime (also known as slaked lime, high calcium lime or air lime). Ancient lime plaster often contained horse hair for reinforcement and pozzolan ...

, and waterproofing. They studied animal physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

, anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

, behavior

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems or artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or organisms as we ...

, and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

for divinatory

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

purposes. The Mesopotamians had an intense interest in medicine and the earliest medical prescription

A prescription, often abbreviated or Rx, is a formal communication from a physician or other registered health-care professional to a pharmacist, authorizing them to dispense a specific prescription drug for a specific patient. Historicall ...

s appeared in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

. They seem to study scientific subjects which have practical or religious applications and have little interest of satisfying curiosity.

Classical antiquity

In

In classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, there is no real ancient analog of a modern scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosop ...

. Instead, well-educated, usually upper-class, and almost universally male individuals performed various investigations into nature whenever they could afford the time. Before the invention or discovery of the concept

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks of the concept behind principles, thoughts and beliefs.

They play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied by ...

of '' phusis'' or nature by the pre-Socratic philosopher

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

s, the same words tend to be used to describe the natural "way" in which a plant grows,An account of the pre-Socratic use of the concept of φύσις may be found in and in The word φύσις, while first used in connection with a plant in Homer, occurs early in Greek philosophy, and in several senses. Generally, these senses match rather well the current senses in which the English word ''nature'' is used, as confirmed by (volume 2 of his ''History of Greek Philosophy''), Cambridge UP, 1965. and the "way" in which, for example, one tribe worships a particular god. For this reason, it is claimed that these men were the first philosophers in the strict sense and the first to clearly distinguish "nature" and "convention".

The early Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

of the Milesian school

The Ionian school of Pre-Socratic philosophy was centred in Miletus, Ionia in the 6th century BC. Miletus and its environment was a thriving mercantile melting pot of current ideas of the time. The Ionian School included such thinkers as Thales, ...

, which was founded by Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

and later continued by his successors Anaximander

Anaximander (; grc-gre, Ἀναξίμανδρος ''Anaximandros''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 403. a city of Ionia (in mo ...

and Anaximenes, were the first to attempt to explain natural phenomena

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

without relying on the supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

. The Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

developed a complex number philosophy and contributed significantly to the development of mathematical science. The theory of atoms was developed by the Greek philosopher Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and his student Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

. The Greek doctor Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

established the tradition of systematic medical science and is known as " The Father of Medicine".

A turning point in the history of early philosophical science was Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

' example of applying philosophy to the study of human matters, including human nature, the nature of political communities, and human knowledge itself. The Socratic method

The Socratic method (also known as method of Elenchus, elenctic method, or Socratic debate) is a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw ou ...

as documented by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's dialogues is a dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

method of hypothesis elimination: better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. The Socratic method searches for general commonly-held truths that shape beliefs and scrutinizes them for consistency. Socrates criticized the older type of study of physics as too purely speculative and lacking in self-criticism

Self-criticism involves how an individual evaluates oneself. Self-criticism in psychology is typically studied and discussed as a negative personality trait in which a person has a disrupted self-identity. The opposite of self-criticism would be ...

.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

in the 4th century BCE created a systematic program of teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

philosophy. In the 3rd century BCE, Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the ...

was the first to propose a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

of the universe, with the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at the center and all the planets orbiting it. Aristarchus's model was widely rejected because it was believed to violate the laws of physics, while Ptolemy's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it can ...

'', which contains a geocentric description of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, was accepted through the early Renaissance instead. The inventor and mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists ...

made major contributions to the beginnings of calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizati ...

. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

was a Roman writer and polymath, who wrote the seminal encyclopedia '' Natural History''.

Middle Ages

Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in

Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. During the period, Latin encyclopedists such as Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville ( la, Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) was a Spanish scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of ...

preserved the majority of general ancient knowledge. In contrast, because the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

resisted attacks from invaders, they were able to preserve and improve prior learning. John Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tr ...

, a Byzantine scholar in the 500s, started to question Aristotle's teaching of physics, introducing the theory of impetus. His criticism served as an inspiration to medieval scholars and Galileo Galilei, who extensively cited his works ten centuries later.

During late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English h ...

and the early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, natural phenomena were mainly examined via the Aristotelian approach. The approach includes Aristotle's four causes

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, four fundamental types of answer to the question "why?", in analysis of change or movement in nature: the material, the formal, the efficient, and the final. Aristotle wrote th ...

: material, formal, moving, and final cause. Many Greek classical texts were preserved by the Byzantine empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

translations were done by groups such as the Nestorians

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian N ...

and the Monophysites

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incar ...

. Under the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, these Arabic translations were later improved and developed by Arabic scientists. By the 6th and 7th centuries, the neighboring Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

established the medical Academy of Gondeshapur, which is considered by Greek, Syriac, and Persian physicians as the most important medical center of the ancient world.

The House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

was established in Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

-era Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, where the Islamic study of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the so ...

flourished until the Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation ...

in the 13th century. Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

, better known as Alhazen, began experimenting as a means to gain knowledge See p. 464: "Schramm sums up bn Al-Haytham'sachievement in the development of scientific method.", p. 465: "Schramm has demonstrated .. beyond any dispute that Ibn al-Haytham is a major figure in the Islamic scientific tradition, particularly in the creation of experimental techniques." p. 465: "only when the influence of ibn al-Haytam and others on the mainstream of later medieval physical writings has been seriously investigated can Schramm's claim that ibn al-Haytam was the true founder of modern physics be evaluated." and disproved Ptolemy's theory of vision Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

's compilation of the Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

, a medical encyclopedia, is considered to be one of the most important publications in medicine and was used until the 18th century.

By the eleventh century, most of Europe had become Christian, and in 1088, the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in contin ...

emerged as the first university in Europe. As such, demand for Latin translation of ancient and scientific texts grew, a major contributor to the Renaissance of the 12th century

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass idea ...

. Renaissance scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translat ...

in western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

flourished, with experiments done by observing, describing, and classifying subjects in nature. In the 13rd century, medical teachers and students at Bologna began opening human bodies, leading to the first anatomy textbook based on human dissection by Mondino de Luzzi.

Renaissance

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, both by challenging long-held metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

ideas on perception, as well as by contributing to the improvement and development of technology such as the camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or lens at one side through which an image is projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions such as a box or tent in w ...

and the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

. At the start of the Renaissance, Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through emp ...

, Vitello, and John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under ...

each built up a scholastic ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophy, philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, Becoming (philosophy), becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into Category ...

upon a causal chain beginning with sensation, perception, and finally apperception Apperception (from the Latin ''ad-'', "to, toward" and ''percipere'', "to perceive, gain, secure, learn, or feel") is any of several aspects of perception and consciousness in such fields as psychology, philosophy and epistemology.

Meaning in philo ...

of the individual and universal forms

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form also refers to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter data

* ...

of Aristotle. A model of vision later known as perspectivism

Perspectivism (german: Perspektivismus; also called perspectivalism) is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism reg ...

was exploited and studied by the artists of the Renaissance. This theory uses only three of Aristotle's four causes: formal, material, and final.

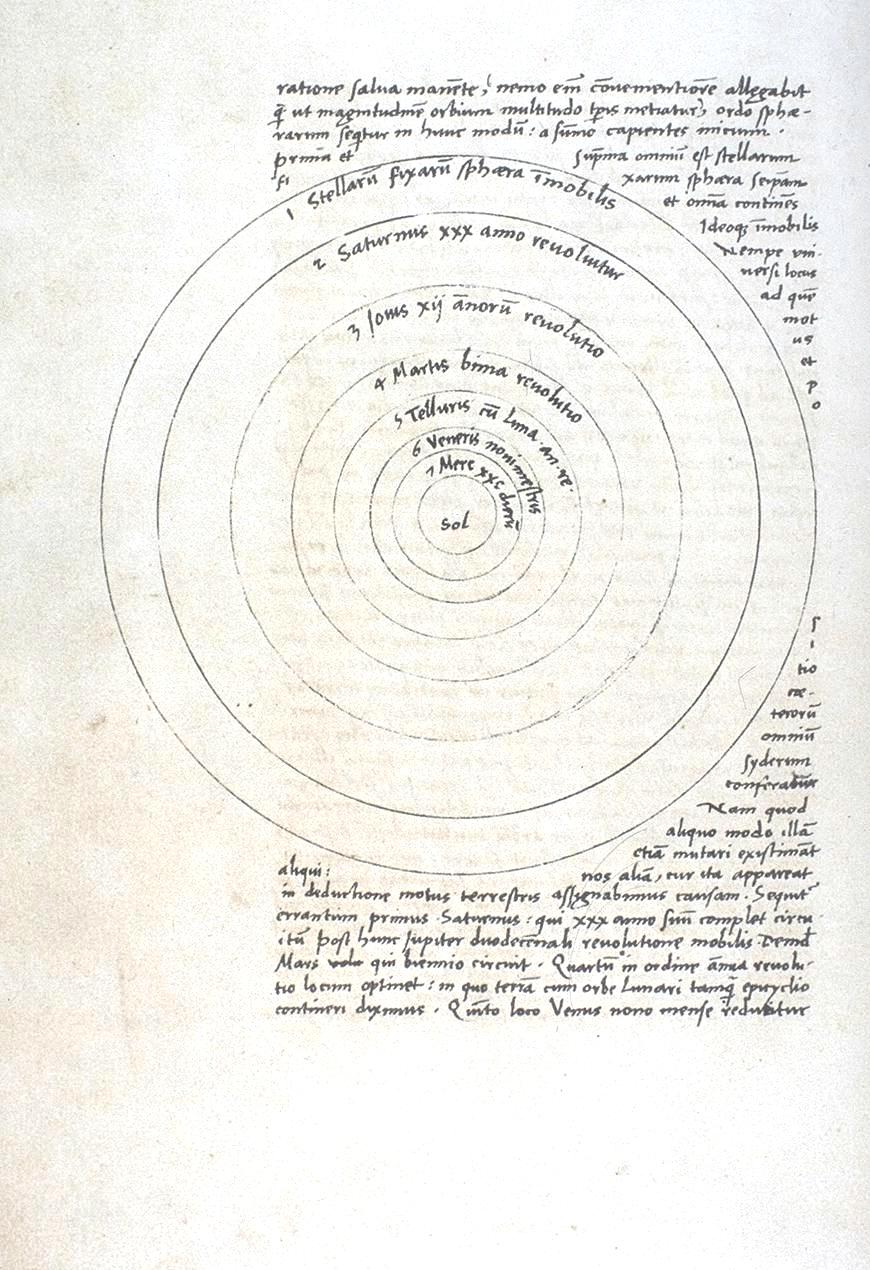

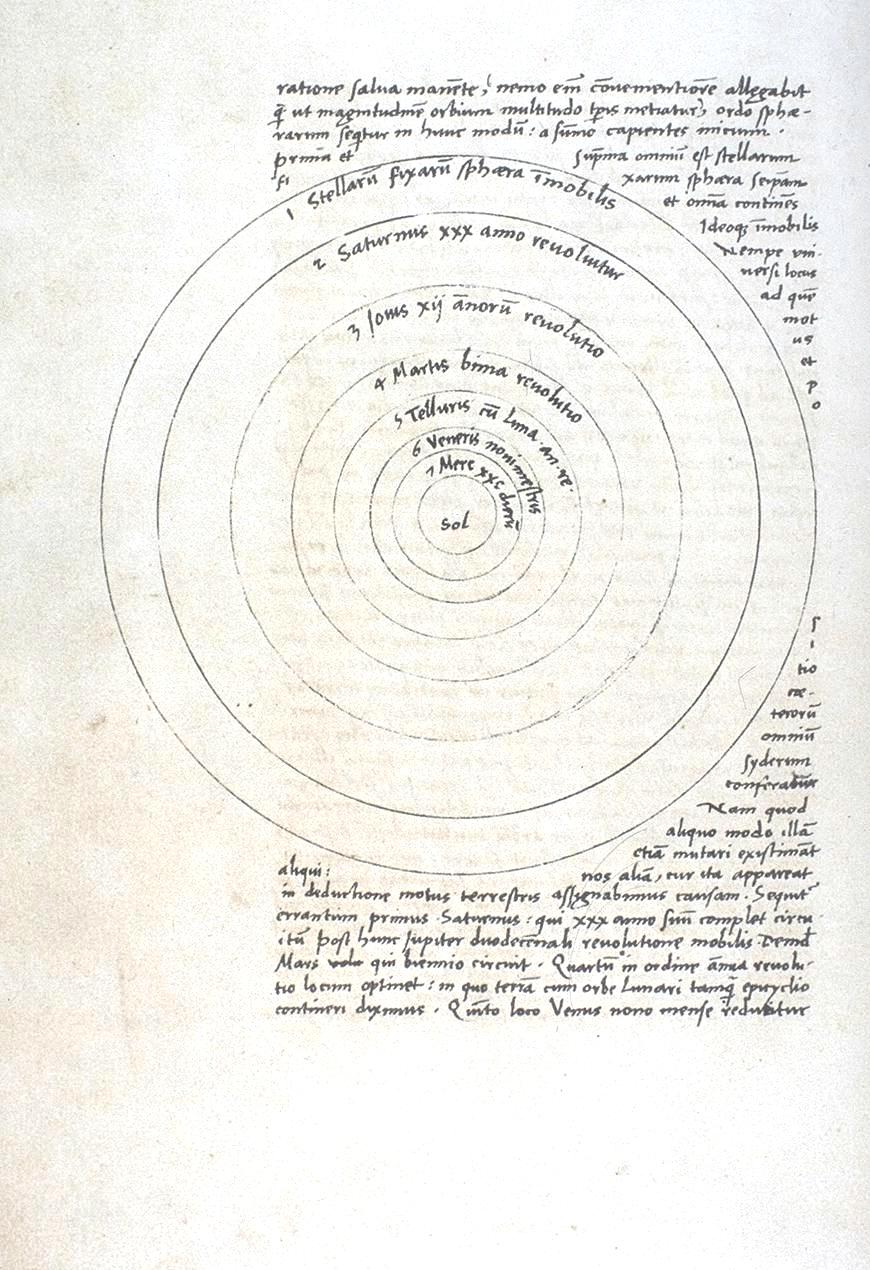

In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

formulated a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

of the Solar System, stating that the planets revolve around the Sun, instead of the geocentric model