Schuyler Skaats Wheeler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Schuyler Skaats Wheeler (May 17, 1860 – April 20, 1923) was an American

Wheeler was educated at

Wheeler was educated at

File:Crocker-Wheeler blind coil winders.jpg, Crocker-Wheeler main plant blind coil winders for electrical motors

File:Crocker-Wheeler blind employees on transformer parts.jpg, Crocker-Wheeler main plant blind workers making transformers

File:Crocker-Wheeler blind employees on notching machines.jpg, Crocker-Wheeler main plant blind workers on notching machines

File:Finger Guild.jpg, Double-Duty Finger Guild of Crocker-Wheeler Company, department for the blind auxiliary factory and training center.

File:Blind workers taping armature coils.jpg, Crocker-Wheeler blind workers training to tape electric motor armature coils at the Double-Duty Finger Guild.

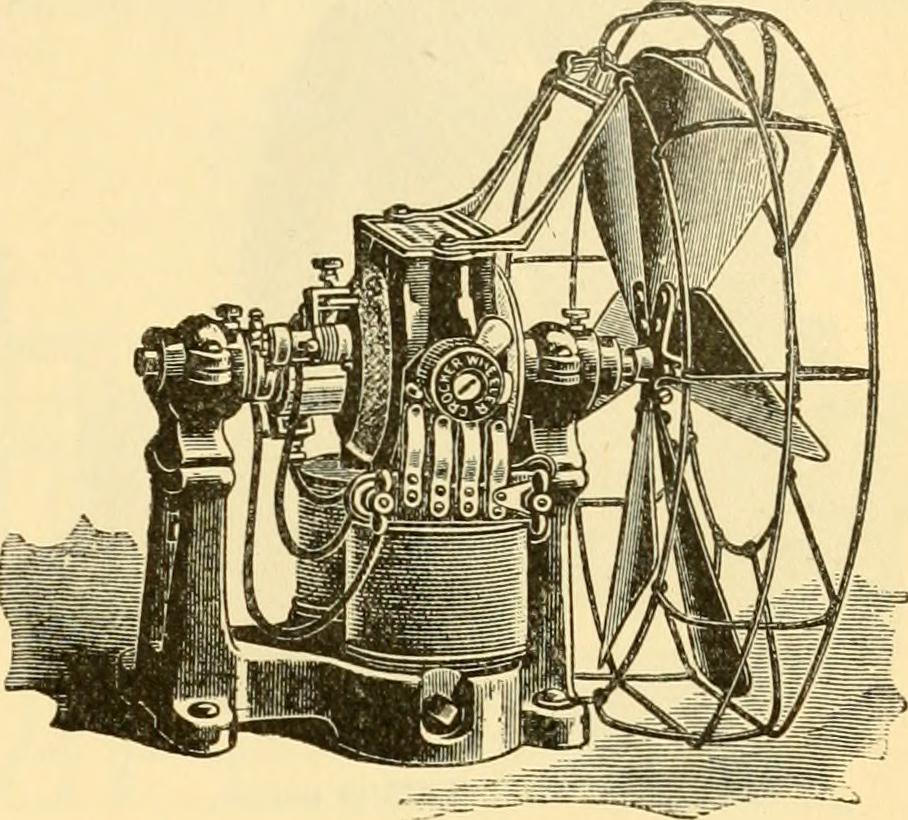

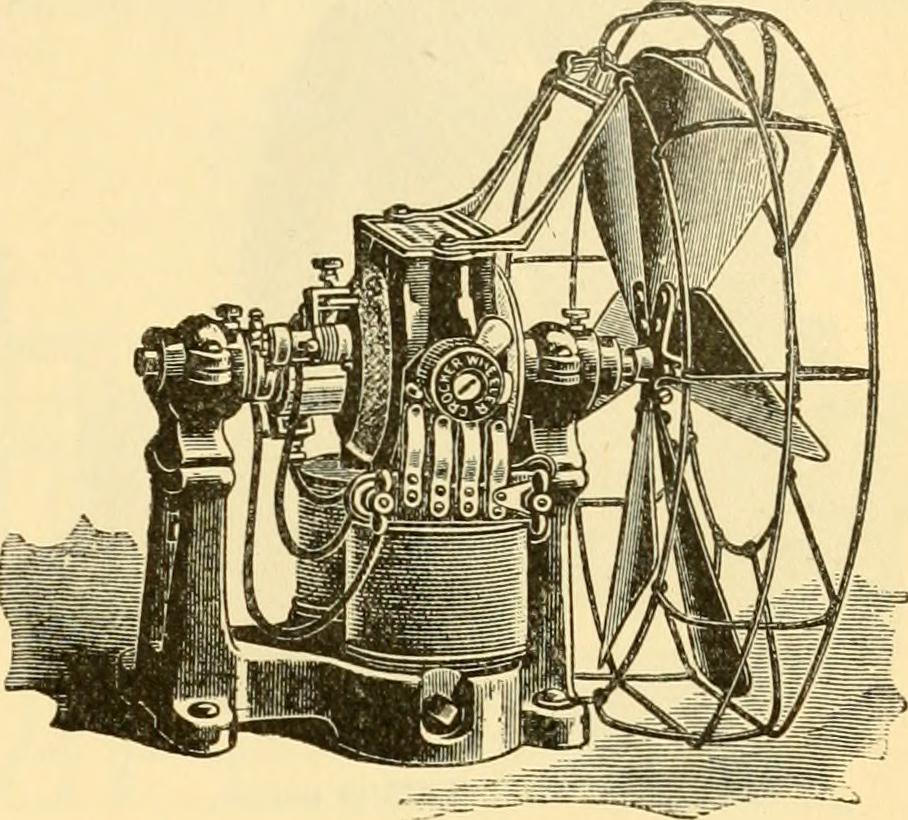

Electric Fire Engine Patent art work

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wheeler, Schuyler American inventors Engineers from New York City American physicists 1860 births 1923 deaths Businesspeople from New York City Writers from New York City Scientists from New York City Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School alumni

electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and manufacturer who invented the electric fan

A fan is a powered machine used to create a flow of air. A fan consists of a rotating arrangement of vanes or blades, generally made of wood, plastic, or metal, which act on the air. The rotating assembly of blades and hub is known as an ''imp ...

, an electric elevator

An elevator or lift is a wire rope, cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or deck (building), decks of a building, watercraft, ...

design, and the electric fire engine

The electric fire engine is a fire engine with a water pump, used to distribute water to put out a fire, operated by an electric motor. Electric fire engines were first proposed in the 19th century to replace the steam pumpers used for firefight ...

. He is associated with the early development of the electric motor industry, especially to do with training the blind in this industry for gainful employment. He helped develop and implement a code of ethics

Ethical codes are adopted by organizations to assist members in understanding the difference between right and wrong and in applying that understanding to their decisions. An ethical code generally implies documents at three levels: codes of bus ...

for electrical engineers and was associated with the electrical field in one way or another for over thirty years.

Early life and genealogy

Wheeler was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on May 17, 1860. He was the son of James Edwin and Ann Wood (Skaats) Wheeler. His father, a lawyer in New York city, was the son of Aaron Reed Wheeler, a land speculator of Waterloo, New York

Waterloo is a town in Seneca County, New York, United States. The population was 7,338 at the 2020 census. The town and its major community are named after Waterloo, Belgium, where Napoleon was defeated.

There is also a village called Water ...

, who came originally from Blackstone, Massachusetts

Blackstone is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 9,208 at the 2020 census. It is a part of the Providence metropolitan area.

History

This region was first inhabited by the Nipmuc. Blackstone was settl ...

. Wheeler's mother was the daughter of David Schuyler Skaats, the president of the First National Bank of Waterloo, New York. Skaats was an eighth generation descendant of Dominie Gideon Skaats, who had settled in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

, prior to 1650.

Mid life and career

Wheeler was educated at

Wheeler was educated at Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School

Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School ("Columbia Grammar", "Columbia Prep", "CGPS", "Columbia") is the oldest nonsectarian independent school in New York City, located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan (5 West 93rd Street). The school serves gr ...

. Leaving college in 1881, upon the death of his father, he became assistant electrician of the Jablochkov Electric Lighting Company. Wheeler then joined the United States Electric Lighting Company in 1883 when Jablochkov went out of business with his electric company. He joined the engineering staff of Thomas A. Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

and was part of the project when the Pearl Street Station

Pearl Street Station was the first commercial central power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl Street in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City, just south of Fulton Street on a site measuring . The station ...

debuted the first incandescent light bulb

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxida ...

s. He acted as general manager of the underground distribution system at Newburgh, New York

Newburgh is a city in the U.S. state of New York, within Orange County. With a population of 28,856 as of the 2020 census, it is a principal city of the Poughkeepsie–Newburgh–Middletown metropolitan area. Located north of New York City, a ...

. He was afterwards in charge to lay the Edison underground systems in other cities.

Wheeler worked for Herzog Teleseme Company as electrician for a short time between 1884 and 1885. Then in 1886 he was part of developing and organizing the C and C Electric Motor Company with Charles G. Curtis and Francis B. Crocker. They were pioneer manufacturers of small electric motors. Wheeler became their main technician and plant manager. Wheeler then left the firm as did Crocker in 1888. They organized the electrical engineering firms of Crocker-Wheeler Motor Company of New York state and the Crocker-Wheeler Company of the state of New Jersey. Wheeler was president of both the firms from 1889. During his tenure with Crocker-Wheeler, he was particularly important in development of the electric motors

An electric motor is an electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a wire winding to generate force ...

and applying it to machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All m ...

drives. He was for seven years (1888–1895) the electrical expert consultant specialist of the Board of Electrical Control of New York.

In 1900, he purchased the library of Josiah Latimer Clark

Josiah Latimer Clark FRS FRAS (10 March 1822 – 30 October 1898), was an English electrical engineer, born in Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire.

Biography

Josiah Latimer Clark was born in Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire, and was younger brother ...

, which contained the largest collection of rare electrical works then known. He donated the Latimer Clark Library collection and it became the foundation of the library housed in New York's Engineering Societies' Building

The Engineering Societies' Building, also known as 25 West 39th Street, is a commercial building at 25–33 West 39th Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, United States. Located one block south of Bryant Park, it was ...

. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) is a 501(c)(3) professional association for electronic engineering and electrical engineering (and associated disciplines) with its corporate office in New York City and its operation ...

(IEEE) recognized him as one those who had given outstanding service to the Institute. In his IEEE presidential address in 1906, he was the progenitor of the ''Code of Ethics

Ethical codes are adopted by organizations to assist members in understanding the difference between right and wrong and in applying that understanding to their decisions. An ethical code generally implies documents at three levels: codes of bus ...

'' for electrical engineers

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the ...

, which was adopted in 1912 by the Institute's Board of Directors.

Inventions

Wheeler invented many electrical devices. He specialized in power saving electrical tools. In 1882 he invented the electric fan by placing a two-bladed propeller on the shaft of an electric motor. It was known as the "buzz fan." He was awarded theJohn Scott Medal

John Scott Award, created in 1816 as the John Scott Legacy Medal and Premium, is presented to men and women whose inventions improved the "comfort, welfare, and happiness of human kind" in a significant way. "...the John Scott Medal Fund, establish ...

for this invention in 1904 by the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

. Wheeler's patent for his Electric Fire-engine System was filed May 23, 1882. The United States Patent Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alexa ...

officially approved his invention on February 24, 1885.

Wheeler invented the use of the electric motor in connection the Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a cyc ...

which reduced the work of the operator when firing to simply pressing a button. It is one of the earliest applications of electricity to machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s. He invented paralleling of dynamo

file:DynamoElectricMachinesEndViewPartlySection USP284110.png, "Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator (electric), commutator. Dynamos were the f ...

s and series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used in ...

multiple motor control. In 1883 he patented an electric elevator design.

Electrical balloting apparatus

Wheeler devised an electrical voting device in 1907. This came about through theAutomobile Club of America

The Automobile Club of America was the first automobile club formed in America in 1899. The club was dissolved in 1932 following the Great Depression and declining membership.

History

On June 7, 1899, a group of gentlemen auto racers met at the W ...

membership application process of the time. Formerly the board of governors made use of an old-fashioned method of dropping a small colored ball into a ballot box to determine their approval or disapproval of the applicant. The black and white ball plan of indicating a yes or no vote was good as long as there were not many applicants for membership. The balloting became very time consuming when the list of applicants became large. This was due to the mechanical handling of the little balls and the repository

Repository may refer to:

Archives and online databases

* Content repository, a database with an associated set of data management tools, allowing application-independent access to the content

* Disciplinary repository (or subject repository), an ...

ballot box.

A new technology was invented by Wheeler that used electricity for instantaneous voting and immediate results. He was the club's first vice president and the consulting engineer. His innovation was to have each club member just sit in his chair and press a button for their vote. This would transmit their vote electrically to the central ballot box. Each voter had in his hand a small block of wood in which were two push buttons, one black and the other white. If the member had no objection to the applicant becoming an official member he pressed the white button. Their vote was recorded instantly then at the central location ballot box that received all the member votes electrically. If they thought the club would be better off without the applicant, the voting member pressed the black button for an instant tabulation. These votes, in either case, were in secret and securely tabulated an immediate result.

Later life

The Crocker-Wheeler company of New Jersey was located in the now defunct town ofAmpere

The ampere (, ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to elect ...

. Wheeler innovated a way after World War I to have disabled veterans that became visually impaired from war injuries to become productively employed as self-supporting citizens. Wheeler established an auxiliary factory of the Double-Duty Finger Guild on May 11, 1917. It was a separate training center and furnished work for the blind. The building was a few blocks away from the main factory and suitable material from the main factory was brought over to this auxiliary facility for the blind to assemble.

These blind workers were paid a minimum wage during training and afterwards promoted to full-time positions to earn a normal income. One of their duties at first was the taping of wire coils which were on the armatures of electric motors. This was easily learned and advanced work was soon taught of winding wire coils for electric motors and transformers. The trainees were given a minimum wage at the beginning and then promoted to the regular wage earned by sighted employees. Wheeler traveled to Europe in 1918 to explain to the French and British governments this system he used for the blind.

The superintendent of the main factory suggested that some of the more talented blind trainees could work at the main factory. The result of that idea was that these blind people were given the opportunity to work side by side with the regular employees in the main factory. This plan proved satisfactory and resulted in the testing of processes not known to the normal electrical trade. Special drills and punch presses were used in Wheeler's experiments. He allowed his main factory to be used as a workshop and research facilities in which the blind could test these various unconventional manufacturing techniques.

Personal life

Wheeler was married in 1898 to Ella Adams Peterson, daughter of Richard N. Peterson of New York City. She died in 1900 and he married again in 1901 to Amy Sutton, daughter of John Joseph Sutton ofRye, New York

Rye is a coastal suburb of New York City in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is separate from the Town of Rye, which has more land area than the city. The City of Rye, formerly the Village of Rye, was part of the Town until it r ...

. He was a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

; the American Society of Mechanical Engineers

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) is an American professional association that, in its own words, "promotes the art, science, and practice of multidisciplinary engineering and allied sciences around the globe" via "continuing ...

; the American Institute of Electrical Engineers

The American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) was a United States-based organization of electrical engineers that existed from 1884 through 1962. On January 1, 1963, it merged with the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) to form the Instit ...

(President, 1905–1906; Vice President for three years); the University Club; the Lotus Club; the Lawyers' Club; and the Automobile Club.

Wheeler was one of nine incorporators of the United Engineering Society formed in May 1904 and was one of three representatives of the IEEE. He was also a member of the Efficiency Society with other millionaires. He wrote several technical articles related to electricity in various journals. He wrote articles for Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

under the title, "The Cheap John in Electrical Engineering." In 1894 he joint authored a book titled "The Practical Management of Dynamos and Motors" with Professor Francis B. Crocker.

Wheeler was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

by Hobart College (1894); and a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

by Columbia College (1912). His papers are archived primarily with the IEEE. He died of angina pectoris

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of obstru ...

at his home in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

on April 20, 1923.Staff report (April 21, 1923). Dr. S. S. Wheeler, Inventor, Dead; President of Crocker-Wheeler Co. Dies Suddenly at His Park Av. Home at 63. Engineer and physicist, founder of United Engineering Society. Presented Latimer-Clark Library to American Institute. ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' At the time of his death, he chaired the IEEE committee on "code of principles of professional conduct."

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *External links

Electric Fire Engine Patent art work

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wheeler, Schuyler American inventors Engineers from New York City American physicists 1860 births 1923 deaths Businesspeople from New York City Writers from New York City Scientists from New York City Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School alumni