The Savannah Protest Movement was an American campaign led by civil rights activists to bring an end to the system of racial segregation in

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

. The movement began in 1960 and ended in 1963.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, African Americans in Savannah were subject to

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

that enforced a strict system of racial segregation whereby they were not allowed to use many of the same facilities used by

white people

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

. However, African Americans attempted to push back against this system, and by the 1940s, the

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, under the leadership of

Ralph Mark Gilbert

Ralph Mark Gilbert (March 17, 1899, Jacksonville, Florida - August 23, 1956, New York City) was an American civil rights leader and a Baptist minister.

Religious Ministry

From 1939 until his death in 1956, he was the Pastor of the First African B ...

, organized

voter registration drive

A voter registration campaign or voter registration drive is an effort by a government authority, political party or other entity to register to vote persons otherwise entitled to vote. In some countries, voter registration is automatic, and is car ...

s among the

black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

population and negotiated agreements with moderate city officials to secure certain improvements for the community, including the hiring of African American police officers and greater investment in infrastructure, such as road repairs and the creation of a new high school. By the early 1960s,

W. W. Law had become the president of the local NAACP chapter, with

Hosea Williams

Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He is best known as a trusted member of fellow famed civil ri ...

serving as vice president and head of the local

youth council

Youth councils are a form of youth voice engaged in community decision-making. Youth councils are appointed bodies that exist on local, state, provincial, regional, national, and international levels among governments, non governmental organisati ...

.

On March 16, 1960, the movement began with a series of

sit-ins

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

conducted by several dozen student activists at segregated

lunch counter

A lunch counter (also known as a luncheonette) is, in the US, a small restaurant, similar to a diner, where the patron sits on a stool on one side of the counter and the server or person preparing the food serves from the opposite side of the ...

s throughout downtown Savannah, resulting in the arrest of three protestors at Levy's Department Store. Over the next several months, protestors continued to target segregated facilities with sit-in related protests, in addition to marches, pickets, and other forms of

direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

. Additionally, Williams organized the Chatham County Crusade for Voters to mobilize the city's black

voting bloc A voting bloc is a group of voters that are strongly motivated by a specific common concern or group of concerns to the point that such specific concerns tend to dominate their voting patterns, causing them to vote together in elections. For example ...

to push for change from the city government. By October 1961, a partial agreement was reached to desegregate some facilities in the city, though protesting continued to achieve complete desegregation. By mid-1963, Williams, who by this time had become affiliated with the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

(SCLC), began to hold nighttime marches that saw hundreds of arrests and an instance of rioting that resulted in the burning of at least one building and the mobilization of the

Georgia National Guard

The Georgia National Guard is the National Guard of the U.S. state of Georgia, and consists of the Georgia Army National Guard and the Georgia Air National Guard. (The Georgia State Defense Force is the third military unit of the Georgia Depar ...

. Following this, white businessmen in the city agreed to a full desegregation of the city and the city government, under Mayor

Malcolm Roderick Maclean

Malcolm Roderick Maclean (September 14, 1919 – January 24, 2001) was a politician from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States and was a former Mayors of Savannah, Georgia, Mayor of Savannah. He was a Democratic Party (United States), ...

, agreed to rescind all remaining segregation ordinances. This officially came into effect on October 1, bringing an end to the movement.

The Savannah movement is notable among protests of the

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

for its length, its achievement of full desegregation, and for the general lack of violence when compared to other movements, such as the

Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts o ...

. Following the movement, Williams left Savannah to become a member of the SCLC national board, where he led a nationwide voter registration program during the 1960s. Meanwhile, in Savannah, Law served as NAACP local president until retiring in 1976. In 2016, the

Georgia Historical Society

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) is a statewide historical society in Georgia. Headquartered in Savannah, Georgia, GHS is one of the oldest historical organizations in the United States. Since 1839, the society has collected, examined, and ta ...

installed a

Georgia historical marker

A Historic marker is an "Alamo"-shaped plaque affixed to the top of a pole and erected next to a significant historic site, battlefield or county courthouse. In the state of Georgia there are roughly 2,000 historic markers. Kevin Levin of the ...

to commemorate the protest movement at the site of the former Levy's Department Store.

Background

Early history of Savannah, Georgia

The city of

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, was founded in 1733, making it the oldest city in the state and one of the oldest in the United States. At its founding, the city was a farming community where

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was banned, though the institution became legal in 1750 and, in the following years, Savannah became a major

port city

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the city was captured by General

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

in December 1864 at the conclusion of his

March to the Sea, leaving the city relatively undamaged. The following month, while still in the city, Sherman issued

Special Field Orders No. 15

Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865) were military orders issued during the American Civil War, on January 16, 1865, by General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi of the United States Army. They p ...

, which gave

newly freed black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

confiscated land from

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

, though these orders were reversed later that year by President

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

. In the latter half of the 19th century, after the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, African Americans in the Southern United States faced economic and political persecution and discrimination under a system of laws known as

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

.

Developments during the late 19th and early 20th century

In Savannah, one of the earliest examples of organized opposition to

racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

in the post-Reconstruction era came in the 1890s, when a boycott prevented the city's

buses

A bus (contracted from omnibus, with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but is also in use for cha ...

from becoming

racially segregated

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Internati ...

. The city's public transit would remain one of the only

racially integrated systems in the region until they became segregated in 1907. By the early 1900s, Savannah boasted numerous

African American businesses, including seven banks, with the city's

black community

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

centered on

West Broad Street, near

Savannah Union Station

Savannah Union Station was a train station in Savannah, Georgia. It was located at 419 through 435 West Broad Street, between Stewart and Roberts streets, on the site that is now listed as 435 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. It hosted the Atl ...

. Additionally, several chapters of national African American organizations were founded prior to the end of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

), whose offices were on West Broad Street, the

National Negro Business League

The National Negro Business League (NNBL) was an American organization founded in Boston in 1900 by Booker T. Washington to promote the interests of African-American businesses. The mission and main goal of the National Negro Business League was ...

, and the

National Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

. This coincided with a statewide growth in these organizations, which established chapters in other Georgia cities, such as

Albany,

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, and

Augusta. However, during the

Interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, violent opposition from

white Americans

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

, including multiple

lynchings

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

, as well as the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, seriously hurt these organizations' efforts and led to the closure of many local chapters. By the 1930s, organized protest against discrimination in the state occurred almost exclusively in either Atlanta or Savannah, and by 1940, according to historian Mark Newman, the NAACP in Georgia was "moribund". The previous year, the

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

for the Savannah NAACP chapter had been revoked due to a precipitous decline in membership.

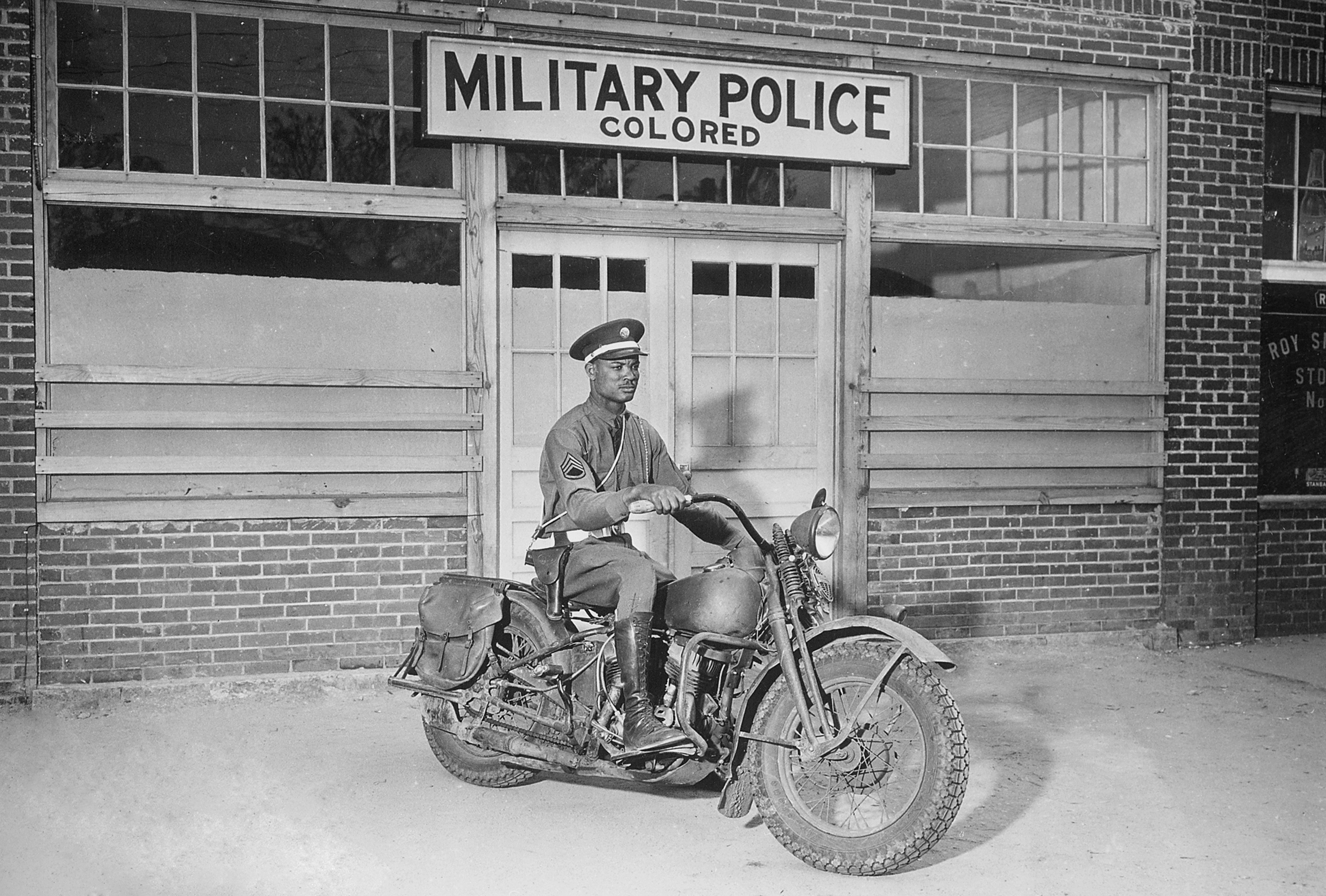

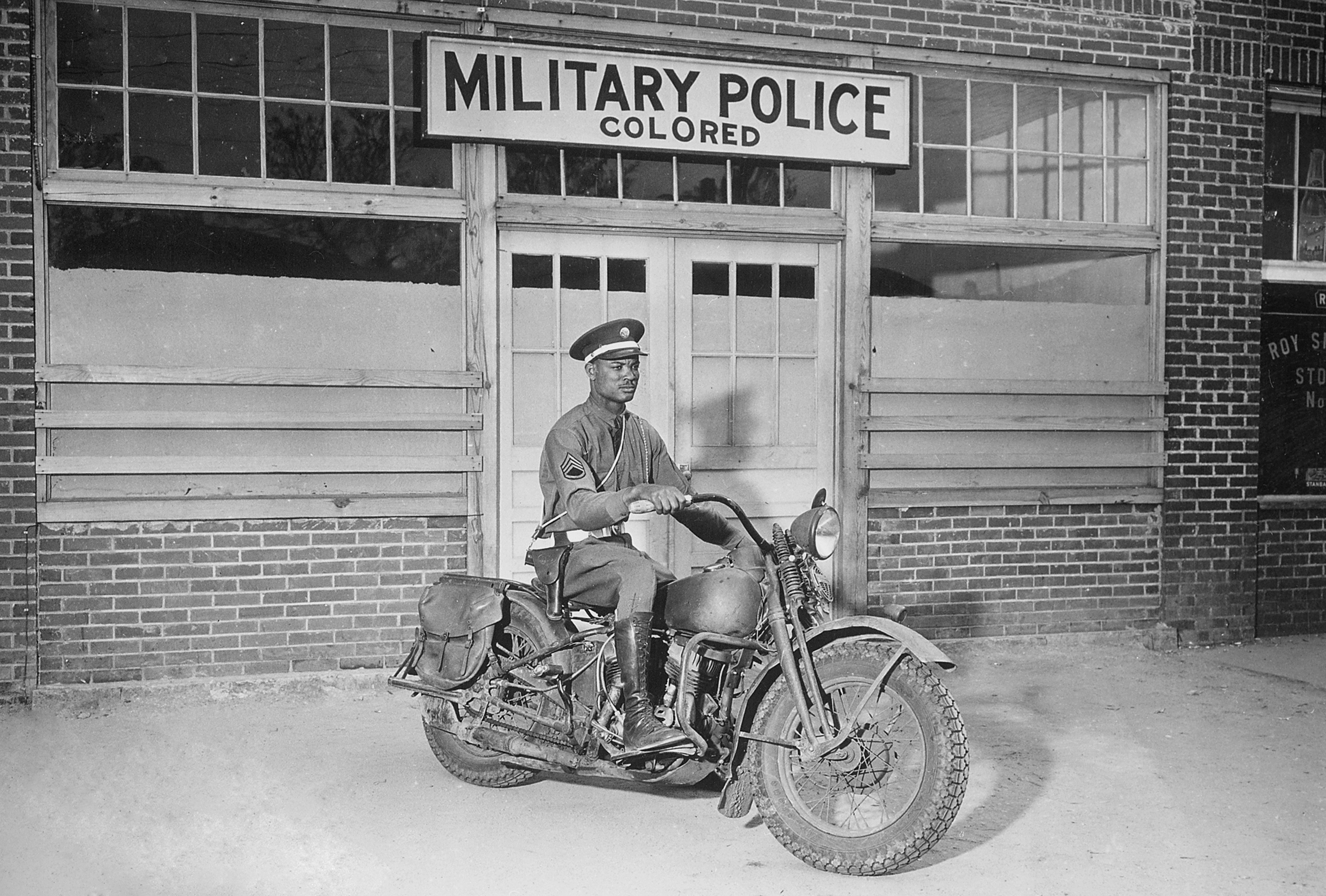

Impact of World War II

The Great Depression and, later, the

United States's involvement in World War II contributed to the migration of approximately 1 million African Americans from rural areas to the urban centers of the American South, such as Atlanta and Savannah, and by 1940, one-third of the 1 million African Americans in Georgia lived in municipalities with populations greater than 5,000. The war contributed to a surge in employment for African Americans, with many in Savannah finding employment in the

war effort

In politics and military planning, a war effort is a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and human—towards the support of a military force. Depending on the militarization of the culture, the relative size ...

and in the city's

shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance a ...

. Across the Southern United States, black Americans gained 1 million new jobs during the war. By 1946, Savannah had over 100 black-owned businesses and a growing

black middle class

The African-American middle class consists of African-Americans who have middle-class status within the American class structure. It is a societal level within the African-American community that primarily began to develop in the early 1960s, ...

, which contributed to a new, developing opposition to discrimination. According to historian

Stephen Tuck, "The emergence of small pockets of relatively prosperous black Georgians in cities, therefore, provided the environment from which civil rights leadership could spring". Also during the war, over 100,000 black men were stationed in several

military bases in the state. In several bases, such as

Camp Gordon

Fort Gordon, formerly known as Camp Gordon, is a United States Army installation established in October 1941. It is the current home of the United States Army Signal Corps, United States Army Cyber Command, and the Cyber Center of Excellence. It ...

near Augusta,

Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

near

Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

, and

Camp Stewart

Fort Stewart is a United States Army post in the U.S. state of Georgia. It lies primarily in Liberty and Bryan counties, but also extends into smaller portions of Evans, Long and Tattnall counties. The population was 11,205 at the 2000 census. Th ...

near Savannah, these African American

enlisted men

An enlisted rank (also known as an enlisted grade or enlisted rate) is, in some armed services, any rank below that of a commissioned officer. The term can be inclusive of non-commissioned officers or warrant officers, except in United States mi ...

became involved in several instances of militant opposition to discrimination, including a

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

of black soldiers at Camp Stewart caused primarily by poor living conditions. These acts were, according to Tuck, some of the first acts of militant opposition to discrimination witnessed by African Americans in the state, and following the war, many black

veterans

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in a military.

A military veteran that has ...

became active participants in further anti-discrimination protests.

Reinvigorated efforts for civil rights

During the 1940s, several political developments occurred in Georgia at the state level that increased African Americans' electoral opportunities. First, in 1943, the

voting age

A voting age is a minimum age established by law that a person must attain before they become eligible to vote in a public election. The most common voting age is 18 years; however, voting ages as low as 16 and as high as 25 currently exist

(s ...

was reduced from 21 to 18. Then, in 1944, the state's

white primary

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South C ...

system was abolished. Finally, in 1945, the

poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

was ended. Some of these

electoral reforms were implemented by

Georgia Governor

The governor of Georgia is the head of government of Georgia and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor also has a duty to enforce state laws, the power to either veto or approve bills passed by the Georgia Legisl ...

Ellis Arnall

Ellis Gibbs Arnall (March 20, 1907December 13, 1992) was an American politician who served as the 69th Governor of Georgia from 1943 to 1947. A liberal Democrat, he helped lead efforts to abolish the poll tax and to reduce Georgia's voting age ...

, a

political moderate

Moderate is an ideological category which designates a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion. A moderate is considered someone occupying any mainstream position avoiding extreme views. In American p ...

who had beaten incumbent

Eugene Talmadge

Eugene Talmadge (September 23, 1884 – December 21, 1946) was an attorney and American politician who served three terms as the 67th governor of Georgia, from 1933 to 1937, and then again from 1941 to 1943. Elected to a fourth term in November ...

in the

1942 election thanks to support from white

liberals. Around this same time, activists in the state, especially consisting of

black women

Black women are women of sub-Saharan African and Afro-diasporic descent, as well as women of Australian Aboriginal and Melanesian descent. The term 'Black' is a racial classification of people, the definition of which has shifted over time and acr ...

, began to organize

voter registration drive

A voter registration campaign or voter registration drive is an effort by a government authority, political party or other entity to register to vote persons otherwise entitled to vote. In some countries, voter registration is automatic, and is car ...

s and pushed for the election of moderate politicians at the

local level. Black civic leaders would then negotiate with these elected officials and were able to obtain concessions and agreements that included increased funding for public

black schools and having black

juror

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartiality, impartial verdict (a Question of fact, finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a sentence (law), penalty o ...

s on court cases. Between 1940 and 1946, the number of African Americans registered to vote in the state rose from roughly 20,000 in 1940 to 135,000 in 1946. Voter registration drives were especially successful in the three largest cities in the state: Atlanta, Savannah, and Augusta.

NAACP under Ralph Mark Gilbert

In Savannah, the state's second-largest city, African American activists began voter registration drives as early as 1941. In April 1942, the NAACP branch in Savannah was rechartered with about 300 members. That same year,

Ralph Mark Gilbert

Ralph Mark Gilbert (March 17, 1899, Jacksonville, Florida - August 23, 1956, New York City) was an American civil rights leader and a Baptist minister.

Religious Ministry

From 1939 until his death in 1956, he was the Pastor of the First African B ...

, the pastor at

First African Baptist Church, one of the oldest

black churches

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as the ...

in the United States, became president of the Savannah NAACP and led efforts to revive the organization. Under his leadership, the chapter grew to a membership of 3,000 people, a figure that surprised many NAACP officials, such as

Ella Baker

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and t ...

. Additionally, the branch recruited many younger members and, according to ''

The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

'' magazine, had the largest youth organization in the country by 1943. From 1942 to 1948, Gilbert also served as the president of the Georgia NAACP organization, during which time he oversaw the creation of 50 new NAACP local chapters in the state. By 1946, the NAACP had 13,595 members in the state, up from under 1,000 before Gilbert's presidency.

Working with his wife Eloria, Gilbert organized youth volunteers to spearhead mass voter registration drives in Savannah. By 1946, about half of Savannah's 45,000 African Americans were registered to vote, and throughout the decade, Savannah boasted both the highest percentage of African Americans registered to vote and the highest percentage of African Americans in the NAACP in the American South. The creation of this large

voting bloc A voting bloc is a group of voters that are strongly motivated by a specific common concern or group of concerns to the point that such specific concerns tend to dominate their voting patterns, causing them to vote together in elections. For example ...

allowed African Americans in Savannah to negotiate certain agreements with city officials that led to the creation of a new high school,

recreation center

A leisure centre in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia (also called aquatic centres), Singapore and Canada is a purpose-built building or site, usually owned and operated by the city, borough council or municipal district council, where peopl ...

, and swimming pool for the community, as well as road improvements and the hiring of two black jail

matron

Matron is the job title of a very senior or the chief nurse in several countries, including the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and other Commonwealth countries and former colonies.

Etymology

The chief nurse, in other words the person ...

s. Also, according to a report from the

Southern Regional Council

The Southern Regional Council (SRC) is a reform-oriented organization created in 1944 to avoid racial violence and promote racial equality in the Southern United States. Voter registration and political-awareness campaigns are used toward this en ...

, the registration drive had resulted in the election of a "very liberal judge" that resulted in black Savannahians "getting some very sound decisions from the court". Savannah was also the first city in Georgia to create a black

advisory committee

An advisory board is a body that provides non-binding strategic advice to the management of a corporation, organization, or foundation. The informal nature of an advisory board gives greater flexibility in structure and management compared to th ...

for its mayor, establishing a line of communication between the city government and the black community. Possibly most significant was the hiring of nine African American police officers, which, along with hirings around the same time made by the

Atlanta Police Department

The Atlanta Police Department (APD) is a law enforcement agency in the city of Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

The city shifted from its rural-based Marshal and Deputy Marshal model at the end of the 19th century. In 1873, the department was formed with 2 ...

, constituted the first instatements of black policemen in the American South since the Reconstruction era.

In addition to electoral methods, Gilbert also oversaw several instances of

direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

to combat segregation in the city. Gilbert threatened a protest against the management of an all-African American public housing project that resulted in the hiring of several black supervisors, and he led the NAACP in a boycott against a store where the white owner had beaten a black woman. Also under his presidency, there was a demonstration by about 50 students from

Georgia State College

)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public historically black university

, parent = University System of Georgia

, academic_affiliation = Space-grant

, endowment ...

where they boarded a bus and refused to relinquish their seats to white patrons, leading to their arrests. Gilbert also led the drive to establish a

YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

on West Broad Street in the 1940s After the war, the chapter under his leadership supported the

Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

's

Operation Dixie

Operation Dixie was the name of the post-World War II campaign by the Congress of Industrial Organizations to trade union, unionize industry in the Southern United States, particularly the textile industry. Launched in the spring of 1946, the campa ...

, which aimed to

unionize

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

African American workers at the city's shipyard.

Continued challenges to civil rights

Despite the progress in Savannah, which Gilbert called "the most liberal city in the state", African Americans in the state still faced discrimination and violence. For example, in 1946, four African Americans near the city of

Monroe were killed in an act of

mob violence

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

known as the

Moore's Ford lynchings

The Moore's Ford Lynchings, also known as the 1946 Georgia lynching, refers to the July 25, 1946, murders of four young African Americans by a mob of white men. Tradition says that the murders were committed on Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton and ...

, and in 1948, members of the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

(KKK) waged a

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

campaign against African Americans during

that year's gubernatorial election. Similar instances of KKK violence occurred in the

1946 election, spurred by candidate and former Governor Talmadge, who used a little-known provision in the ''

Official Code of Georgia Annotated

The Official Code of Georgia Annotated or OCGA is the compendium of all laws in the U.S. state of Georgia. Like other U.S. state codes, its legal interpretation is subject to the United States Constitution, the United States Code, the Code o ...

'' to effectively

disenfranchise

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

many African Americans. Savannah was still also a segregated city, as evidenced in 1948 when the

Freedom Train

Two national Freedom Trains have toured the United States: the 1947–49 special exhibit Freedom Train and the 1975–76 American Freedom Train which celebrated the United States Bicentennial. Each train had its own special red, white and blue p ...

, a nationwide tour that displayed the original

United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

and

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

in several cities across the country, set up segregated viewing lines in Savannah, which were decried by the

NAACP Youth Council The NAACP Youth Council is a branch of the NAACP in which youth are actively involved. In past years, council participants organized under the council's name to make major strides in the Civil Rights Movement. Started in 1935 by Juanita E. Jackson, ...

as a "shameful disgrace". By 1960, the black

unemployment rate

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the referen ...

in Savannah was about twice that of the white community, and the

median income

The median income is the income amount that divides a population into two equal groups, half having an income above that amount, and half having an income below that amount. It may differ from the mean (or average) income. Both of these are ways of ...

for a black person was about one-third of that for a white person.

Civil rights movement in Savannah

Gilbert served as the president of the Savannah NAACP chapter until 1950, when he was succeeded by

W. W. Law, who, earlier that year, had become a member of the NAACP national board of directors. Law was a mentee of Gilbert's who had served on the NAACP Youth Council while in high school, during which time he served as the group's first president. As part of the youth council, he participated in activism such as protests against the segregation of

Grayson Stadium

William L. Grayson Stadium is a stadium in Savannah, Georgia. It is primarily used for baseball, and is the home field of the Savannah Bananas of the Coastal Plain League collegiate summer baseball league. It was the part-time home of the S ...

. As a civil rights activist, Law was a believer in

nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, cons ...

as an effective means to achieve social change, and he advocated against more violent tactics. In 1942, he enrolled at Georgia State College in Savannah, though he was

drafted into military service after his first year. He later re-enrolled under the provisions of the

G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

and graduated with a degree in biology, after which he found employment with the

United States Post Office Department

The United States Post Office Department (USPOD; also known as the Post Office or U.S. Mail) was the predecessor of the United States Postal Service, in the form of a Cabinet department, officially from 1872 to 1971. It was headed by the postmas ...

as a

mail carrier

A mail carrier, mailman, mailwoman, postal carrier, postman, postwoman, or letter carrier (in American English), sometimes colloquially known as a postie (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom), is an employee of a post ...

. This job helped him in his work with the NAACP, as it kept him in close contact with people throughout the city. In a bit of a departure from Gilbert, Law focused primarily on continuing to maintain the local Savannah chapter and focused less on statewide activism and chapter-building.

Around the same time,

Hosea Williams

Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He is best known as a trusted member of fellow famed civil ri ...

became another noted civil rights activist in Savannah. Williams was a graduate of

Morris Brown College

Morris Brown College (MBC) is a private Methodist historically black liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded January 5, 1881, Morris Brown is the first educational institution in Georgia to be owned and operated entirely by African Ame ...

and

Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University (CAU or Clark Atlanta) is a private, Methodist, historically black research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Clark Atlanta is the first Historically Black College or University (HBCU) in the Southern United States. Founde ...

, both in Atlanta, and had moved to Savannah in the 1950s to work as a

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

for the

United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the United States federal executive departments, federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, ...

at

Savannah State College

)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public historically black university

, parent = University System of Georgia

, academic_affiliation = Space-grant

, endowment ...

. Williams believed that his hiring had been an example of

tokenism

Tokenism is the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to be inclusive to members of minority groups, especially by recruiting people from underrepresented groups in order to give the appearance of racial or gender equality wit ...

, and this, coupled with an experience where one of his children was denied service at a

lunch counter

A lunch counter (also known as a luncheonette) is, in the US, a small restaurant, similar to a diner, where the patron sits on a stool on one side of the counter and the server or person preparing the food serves from the opposite side of the ...

in the city, spurred him to become an activist for civil rights. By the early 1960s, he had become the vice president of the Savannah NAACP chapter under Law, and additionally, headed the local Youth Council. Another noted civil rights leader during this time was Eugene Gadsden, who served as the NAACP local chapter's

legal counsel

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicitor, ...

.

Sit-in movement

Under Law's administration, the NAACP chapter in Savannah continued to grow, with historian Clare Russell stating that this was due in part to "the lack of overt

racial violence

Ethnic violence is a form of political violence which is expressly motivated by ethnic hatred and ethnic conflict. Forms of ethnic violence which can be argued to have the characteristics of terrorism may be known as ethnic terrorism or ethnica ...

which meant that they could organize in relatively security". By 1959, Law began to promote more direct action to combat segregation. Starting in March 1960, the local NAACP chapter began to sponsor weekly meetings at local black churches to keep their members informed about ongoings in the broader

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. Around this time, many young activists in the city were interested in replicating the

Greensboro sit-ins

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in February to July 1960, primarily in the Woolworth store—now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum—in Greensboro, North Carolina, which led to the F. W. Woolworth Comp ...

, a nonviolent protest that had begun in

Greensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte and Raleigh, the 69th-most populous city in the Un ...

, the previous month. As part of the protest, African American activists would go to segregated lunch counters and sit down at them, refusing to leave until they were either served, thrown out, or arrested. These initial protests in Greensboro sparked the larger

sit-in movement

The sit-in movement, sit-in campaign or student sit-in movement, were a wave of sit-ins that followed the Greensboro sit-ins on February 1, 1960 in North Carolina. The sit-in movement employed the tactic of nonviolent direct action and was a p ...

that saw activists in many cities throughout the American South employ similar nonviolent practices to integrate segregated spaces, such as lunch counters, stores, and public facilities.

Course of the protests

1960

First sit-ins

The sit-in movement came to Savannah on March 16, 1960, when several black student activists, led by the NAACP Youth Council, first gathered at First African Baptist before leaving to downtown Savannah, where they performed sit-ins at eight businesses. In addition to the sit-ins, about 80 student protestors led a march through the streets to protest segregation. At the Azalea Room, a lunch counter inside the Levy's Department Store, Carolyn Quilloin, Joan Tyson, and Ernest Robinson were arrested after they continued to try to order after the owner demanded that they leave. In jail, the arrested proceeded to sing "

We Shall Overcome

"We Shall Overcome" is a gospel song which became a protest song and a key anthem of the American civil rights movement. The song is most commonly attributed as being lyrically descended from "I'll Overcome Some Day", a hymn by Charles Albert Ti ...

". At the time of the sit-ins, Robinson had written part of

Psalm 23

Psalm 23 is the 23rd psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The Lord is my shepherd". In Latin, it is known by the incipit, "". The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, and a boo ...

on his palm, and in a later interview with the ''

Savannah Morning News

The ''Savannah Morning News'' is a daily newspaper in Savannah, Georgia. It is published by Gannett. The motto of the paper is "Light of the Coastal Empire and Lowcountry". The paper serves Savannah, its metropolitan area, and parts of South Ca ...

'', Coleman stated, "That verse uplifted us. We were very familiar with what had happened to

Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi in 1955, after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery ...

, a 14-year-old student who was killed in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a White girl across the street. While we thought that we were safe in Savannah, we knew that anything could happen". These three students, all members of the NAACP Youth Council, were

convicted

In law, a conviction is the verdict reached by a court of law finding a defendant guilty of a crime. The opposite of a conviction is an acquittal (that is, "not guilty"). In Scotland, there can also be a verdict of "not proven", which is consid ...

under an anti-

trespassing

Trespass is an area of tort law broadly divided into three groups: trespass to the person, trespass to chattels, and trespass to land.

Trespass to the person historically involved six separate trespasses: threats, assault, battery, wounding, ...

state law and sentenced to either five months in jail or a $100 fine (equivalent to $ in 2021). In addition to Levy's Department Store, other restaurants targeted by the sit-ins included Anton's Restaurant, franchises of

Krystal

Krystal may refer to:

People

* Krystal Ann Simpson (born 1982), American poet, fashion blogger, DJ, reality television personality, and musician

* Krystal Ball (born 1981), American political commentator

* Krystal Barter, Australian activi ...

and

Morrison's Cafeteria

Morrison's Cafeterias was a chain of cafeteria-style restaurants, located in the Southeastern United States with a concentration of locations in Georgia and Florida. Generally found in shopping malls, Morrison's primary competition was Piccadilly ...

, and the lunch counters inside of the downtown

Woolworth's

Woolworth, Woolworth's, or Woolworths may refer to:

Businesses

* F. W. Woolworth Company, the original US-based chain of "five and dime" (5¢ and 10¢) stores

* Woolworths Group (United Kingdom), former operator of the Woolworths chain of shops ...

and

S. H. Kress & Co. Alongside the

Atlanta sit-ins

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, ...

, which began one day earlier, these marked some of the first sit-ins in the state.

Boycott and further protests

On the same day as the sit-ins, the local NAACP announced a boycott of downtown stores. Black civic leaders announced that the boycotts would target segregated businesses and would continue until these businesses were desegregated. In addition to this, they also demanded the hiring of black workers at levels above

menial

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

positions, the desegregation of public drinking fountains and restrooms, and the use of

courtesy title

A courtesy title is a title that does not have legal significance but rather is used through custom or courtesy, particularly, in the context of nobility, the titles used by children of members of the nobility (cf. substantive title).

In some co ...

s, such as Mr., Mrs., and Miss, instead of simply "boy" or "girl", when referring to African Americans. On March 17, the boycott was temporarily placed on hold as Law and several other activists in Savannah traveled to

Sylvania to participate in a hearing of the Sibley Commission, but on March 20, the first mass meeting of the protest movement was held at Bolton Street Baptist Church on West Broad Street. Members at the meeting voted unanimously to officially institute a boycott against downtown businesses, and Law, speaking to an audience of about 1,000 people, stated that the boycotts would continue until integration was achieved. Local churches would serve as regular meeting spots for the duration of the protest, commonly held at either Bolton Street Baptist or St. Philip AME Church.

On March 26, Levy's Department Store became the first store in downtown to be the target of a concerted protest action that saw

picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pick ...

outside the building, with signs bearing slogans such as "You can buy a $50 suit, but not a 10 cent cup of coffee" and "We want a mouthful of freedom". Over the next several weeks, 23 more protestors would be arrested. In April, the city council passed an ordinance banning protesting in front of businesses by two or more people, with a reporter for ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' quoting Savannah Mayor

Lee Mingledorff Jr. as saying, "I don't care whether

he ordinance isespecially constitutional or not". That same month, black marchers in that year's Easter parade wore clothing from last year's march, refusing to patronize downtown stores. By May, the ''

Pittsburgh Courier

The ''Pittsburgh Courier'' was an African-American weekly newspaper published in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from 1907 until October 22, 1966. By the 1930s, the ''Courier'' was one of the leading black newspapers in the United States.

It was acqu ...

'' listed Savannah as "one of the three hot spots of the student movement in the South", alongside

Biloxi, Mississippi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

and

Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the seat of Duval County, with which the ...

.

Other forms of sit-in protests

By August, protesting in Savannah had spread from sit-ins to other nonviolent direct action. On August 17, protestors at the beach on nearby

Tybee Island

Tybee Island is a city and a barrier island located in Chatham County, Georgia, 18 miles (29 km) east of Savannah, United States. Though the name "Tybee Island" is used for both the island and the city, geographically they are not identical ...

conducted a "wade-in", inspired by

a similar protest that had taken place in Biloxi, where they waded into the water on the segregated beach. Protestors, which included student activist Benjamin Van Clarke and future

Georgia House of Representatives

The Georgia House of Representatives is the lower house of the Georgia General Assembly (the state legislature) of the U.S. state of Georgia. There are currently 180 elected members. Republicans have had a majority in the chamber since 2005. T ...

member

Edna Jackson

Edna Davis Jackson (born 1950) is a Tlingit people, Tlingit and Americans, American artist.

Jackson is a native of Petersburg, Alaska, Petersburg, Alaska, and continues to live in the nearby community of Kake, Alaska, Kake; she is the daughter ...

, swam for about 90 minutes before police put an end to the protest and arrested 11 people.

On August 21, student activists affiliated with the NAACP conducted the city's first "kneel-ins", modeled after similar events in Atlanta, when they visited ten white churches. About a week prior to this church desegregation effort, a pastor at a local Methodist church had written an open letter denouncing the planned protests, drawing national media attention. In total, five churches turned away the protestors, three, including the

Lutheran Church of the Ascension, offered to allow them to attend the services in segregated seating, while two,

Christ Church and Tabernacle Baptist Church, allowed them to attend the service in integrated seating. The following Sunday, protestors again conducted "kneel-ins", which saw six churches turning them away and five letting them attend.

By October, activists had participated in numerous forms of protest against segregated facilities, including "wade-ins", "kneel-ins", "ride-ins" in segregated buses, and "stand-ins" at segregated movie theaters, among others. In one instance that activists later referred to as a "piss-in", activist Judson Ford was arrested for unknowingly using a segregated public restroom. At Daffin Park, near

Grayson Stadium

William L. Grayson Stadium is a stadium in Savannah, Georgia. It is primarily used for baseball, and is the home field of the Savannah Bananas of the Coastal Plain League collegiate summer baseball league. It was the part-time home of the S ...

, six black youth were arrested for

breach of the peace

Breach of the peace, or disturbing the peace, is a legal term used in constitutional law in English-speaking countries and in a public order sense in the several jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It is a form of disorderly conduct.

Public ord ...

after they were caught playing basketball in the whites-only park. A lawsuit that rose to the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

eventually overturned the charges against the kids, which carried a fine of $100 ($ in 2021) and five months in prison, as they were ruled unconstitutional.

Voter registration drive

In addition to the boycott, black civic leaders began a massive voter registration drive to mobilize black eligible voters in

Chatham County. To achieve this, Williams organized the Chatham County Crusade for Voters (CCCV), an organization that was structurally independent of, but still received support from, the NAACP. The CCCV, which Tuck described as the "political arm" of the local NAACP, was directly led by Williams. By the end of 1960, thanks in large part to the CCCV's efforts, 57 percent of the eligible black citizens of Savannah were registered to vote, a higher percentage than among the city's white population. In Savannah, a city with a population of about 150,000 where roughly one-third of the population was black, this gave the black voting bloc a great deal of political strength. This political mobilization coincided with the elevation of

Malcolm Roderick Maclean

Malcolm Roderick Maclean (September 14, 1919 – January 24, 2001) was a politician from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States and was a former Mayors of Savannah, Georgia, Mayor of Savannah. He was a Democratic Party (United States), ...

, a city alderman, to the position of mayor to fill a vacancy in the office. Maclean worked with the black community on several agreements, such as the appointment of one black person to each city council board.

1961

In late March 1961, students at

Johnson High School initiated a boycott of classes after the school board announced that they would not be renewing the employment contract for Principal E. C. Cheatham. This boycott, led by Van Clarke, divided the leadership of the protest movement. From the beginning, Gadsden was opposed to the boycott, fearing that it would hurt the NAACP's broader goals for school integration. In Savannah, despite the ruling in ''

Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregat ...

'' stating that school segregation was unconstitutional, the public school system remained racially segregated. Meanwhile, in the beginning, both Law and Williams supported the boycott, with both participating in a rally in support of the student movement on March 23. However, by July, Law was seeking a way to quietly end the boycott.

As opposed to Law, Williams continued to support the boycott and saw potential in Van Clarke as a civil rights activist, inviting him to attend a workshop at the

Dorchester Academy

Dorchester Academy was a school for African-Americans located just outside Midway, Georgia. Operating from 1869 to 1940, its campus, of which only the 1935 Dorchester Academy Boys' Dormitory survives, was the primary site of the Southern Christi ...

in nearby

Liberty County that was run by activist

Septima Poinsette Clark

Septima Poinsette Clark (May 3, 1898 – December 15, 1987) was an African United States, American educator and civil rights activist. Clark developed the literacy and citizenship workshops that played an important role in the drive for votin ...

. Modeled after the

Highlander Folk School

The Highlander Research and Education Center, formerly known as the Highlander Folk School, is a social justice leadership training school and cultural center in New Market, Tennessee. Founded in 1932 by activist Myles Horton, educator Don West (e ...

in

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, the Dorchester Academy was one of a number of "

Citizenship Schools" established throughout the Southern United States with the goal of training civil rights activists and giving African American adults lessons in civics that would help them to navigate the obstacles they faced in exercising their political rights. Many of the students at these schools were middle-aged and offered financial support for the younger protestors. Van Clarke would later serve as the head of the CCCV's youth division and organized as many as three marches per day, including one where protestors dressed in black and carried a casket in a mock funeral for segregation. Throughout the protests, Van Clarke would be arrested 25 times.

In June 1961, with the boycott against downtown stores still in place, Savannah's bus company announced their commitment to hire black drivers. The agreement with the bus company represented a major breakthrough for the activists and demonstrated that the protest was having an effect on local businesses. Since the boycott began the previous year, five businesses had declared bankruptcy, at least partially due to the effects of the protest. According to the local

chamber of commerce

A chamber of commerce, or board of trade, is a form of business network. For example, a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to ad ...

, the boycott had contributed to a 15 percent decrease in revenue for downtown businesses as a whole. On the other side of the protests, segregationists began a counter-boycott of stores that had already desegregated, and protestors continued to face the threat of physical violence, as evidenced by a March 15 report in ''

The Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'' about an activist who was assaulted by a group of white youths during a sit-in at Woolworth's. Also, in July 1961, Law was fired from his job with the postal service due to his civil rights activism, though he was reinstated following pushback against his termination from national NAACP leaders and United States President

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

.

Partial desegregation agreement

By late 1961, merchants in downtown Savannah had pushed the city government to negotiate directly with the protest leaders to bring an end to the boycotting. Mayor Maclean assembled a biracial committee that agreed to several of the protestors' demands, including a commitment to hire black people to higher ranking positions and the use of courtesy titles. Additionally, the city government revoked an ordinance mandating segregated lunch counters and also desegregated many public facilities, including buses, golf courses, movie theaters, and restaurants. This agreement was reached on October 1, and following this, the targeted boycott against downtown businesses came to an end. However, targeted protests still continued against institutions in the city that remained segregated, such as parks, restaurants at the local airport and train station, and the

Savannah Fire Department. In December of that year, the

Central of Georgia Railway

The Central of Georgia Railway started as the Central Rail Road and Canal Company in 1833. As a way to better attract investment capital, the railroad changed its name to Central Rail Road and Banking Company of Georgia. This railroad was cons ...

's ''

Nancy Hanks

Nancy Hanks Lincoln (February 5, 1784 – October 5, 1818) was the mother of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. Her marriage to Thomas Lincoln also produced a daughter, Sarah, and a son, Thomas Jr. When Nancy and Thomas had been married for j ...

'' passenger train was desegregated, with a group of black people riding in the white passenger section on the train's route from Savannah to Atlanta.

Rivalry between Law and Williams

Since 1960, there had a developing rivalry between Law and Williams. This primarily stemmed from Williams's general dissatisfaction with the NAACP leadership's advocacy for more legislative means of achieving civil rights as opposed to more direct forms of protest. Williams, meanwhile, was more in favor of using direct action, as throughout the protests, Williams organized many large marches and rallied, including a

lie-in at Morrison's Cafeteria and rallies at

Johnson Square. Additionally, during his lunch breaks, Williams would often give speeches from atop a boulder monument to

Tomochichi

Tomochichi (to-mo-chi-chi') (c. 1644 – October 5, 1741) was the head chief of a Yamacraw town on the site of present-day Savannah, Georgia, in the 18th century. He gave his land to James Oglethorpe to build the city of Savannah. He remains a p ...

at

Wright Square

Wright is an occupational surname originating in England. The term 'Wright' comes from the circa 700 AD Old English word 'wryhta' or 'wyrhta', meaning worker or shaper of wood. Later it became any occupational worker (for example, a shipwright is ...

, in front of

the city's federal courthouse.

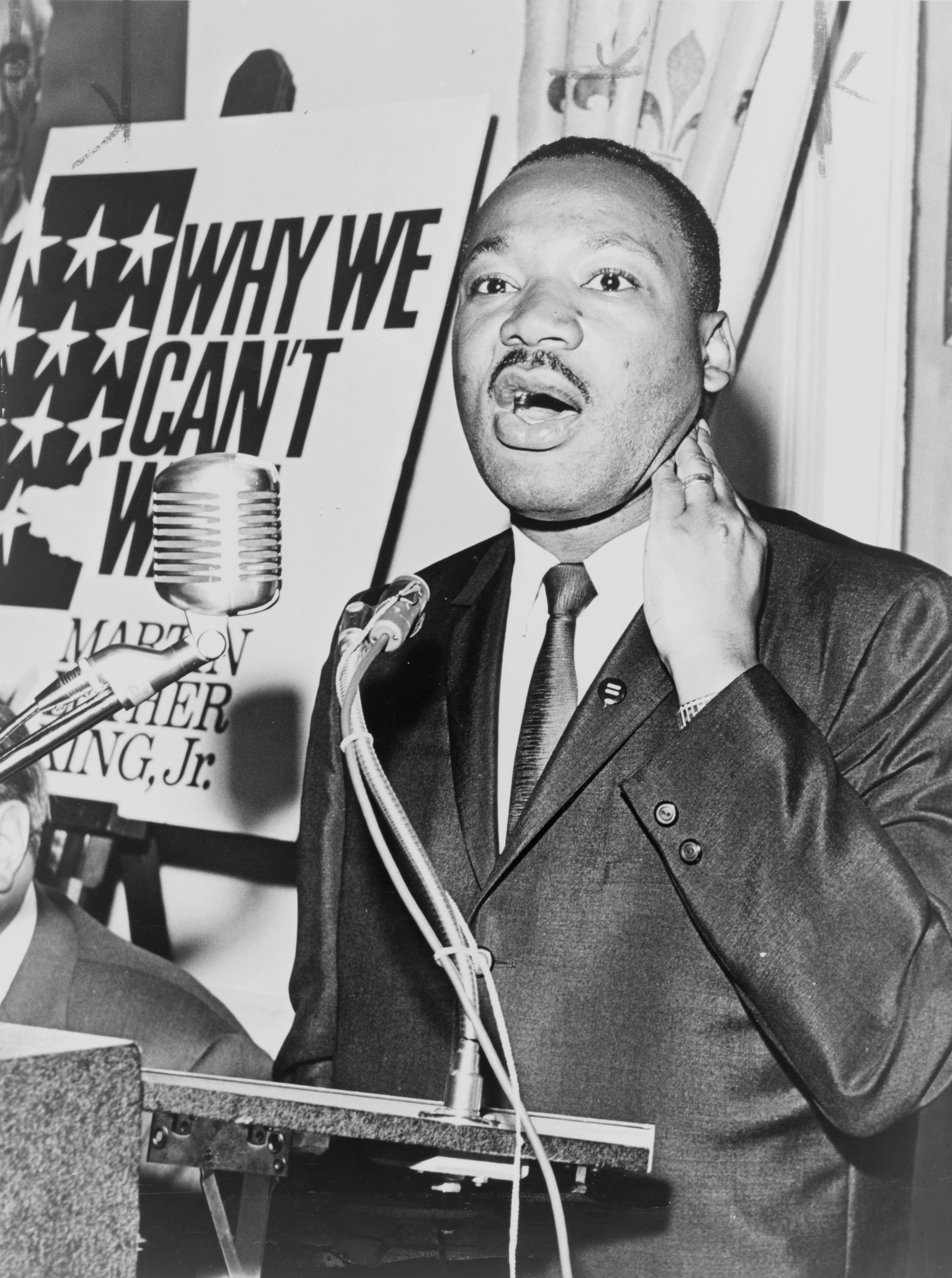

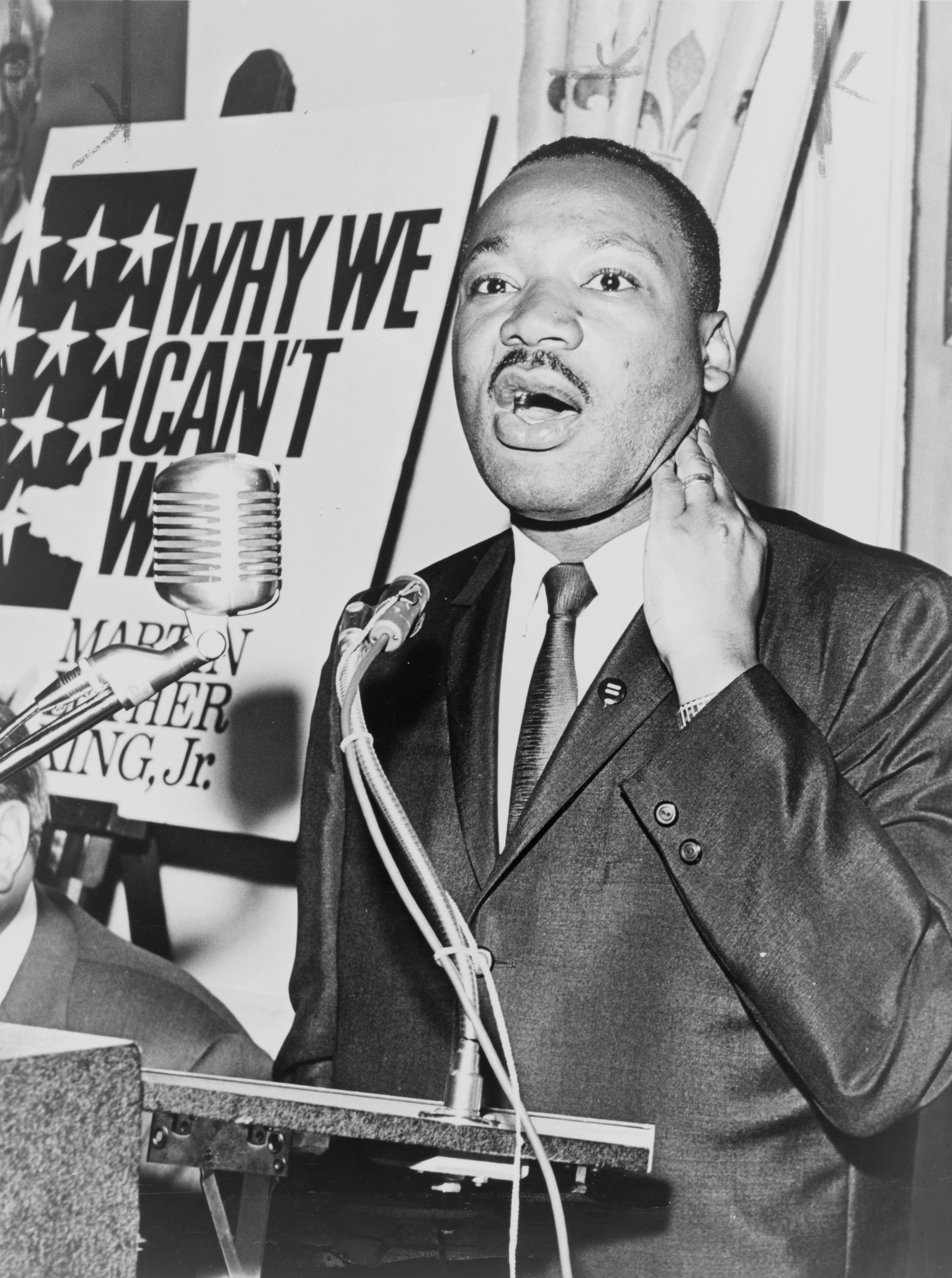

By 1962, the strife between Law and Williams had escalated, driven in part by the NAACP's eventual condemnation of Van Clarke's boycott at Johnson High School, which Williams continued to support. Around October of that year, the rivalry reached a fever pitch when Law refused to support Williams's bid to join the national board of the NAACP. Williams was hurt by the refusal, later saying, "It was kind of like telling a man, 'You don't have your own family. Your family won't vote for you'". Following this, Williams began to pivot away from the NAACP and towards the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

(SCLC). The SCLC, which was led by activist

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, was the group responsible for funding the citizenship schools, including the Dorchester Academy led by Clark. This division ultimately forced many activists in Savannah to pick between Williams and Law, especially when the CCCV became affiliated with the SCLC that year.

1963

Night marches

Through 1963, Williams continued to work closely with the SCLC, eventually joining the organization's national board. In April of that year, he took a brief break from activism in Savannah to bring activists from that city to

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

to help King in his

Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts o ...

. However, on June 4, Savannah's movie theaters resegregated following public pressure from the city's white community, prompting renewed activism in the city. Led primarily by Williams, activists held large marches along

Broughton Street

Broughton Street is a prominent street in Savannah, Georgia, United States. Located between Congress Street to the north and State Street to the south, it runs for about from Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in the west to East Broad Stre ...

during both the day and at night. Williams felt that the night marches would bring national attention to the protest, while Law believed that the night marches would provoke violence that would ultimately hurt the protest. Many other church leaders were opposed to the marches and refused to allow Williams to use their churches for organizing. Despite this, Williams led groups of up to 1,000 protestors on these night marches. These marches were part of a nationwide series of renewed civil rights protest in 1963.

Within one week of the marches beginning, about 500 protestors were arrested, and as violence escalated, Williams asked the SCLC to send protest organizers

James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

,

Dorothy Cotton

Dorothy Cotton (June 9, 1930 – June 10, 2018) was an American civil rights activist, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and a member of the inner-circle of one of its main organizations, the Southern Christian ...

, and

Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christian L ...

to Savannah to teach the protestors more nonviolent tactics. In one march, these organizers led a group of 200 children that ended in all marchers being jailed. On June 12, the Savannah Youth Strategy Committee, a local affiliate of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

(SNCC) that was led by Van Clarke, began protesting against the city after Mayor Maclean failed to follow through on the group's demands to immediately desegregate all public facilities and agree to not arrest activists that were protesting against segregated private facilities. On June 19, a group of about 3,000 protestors held a mass prayer outside of a segregated

Holiday Inn

Holiday Inn is an American chain of hotels based in Atlanta, Georgia. and a brand of IHG Hotels & Resorts. The chain was founded in 1952 by Kemmons Wilson, who opened the first location in Memphis, Tennessee that year. The chain was a division ...

that resulted in 400 arrests. After this, the remaining activists, led by Williams and Van Clarke, gathered outside the local jail to protest the arrests, during which time city and state law enforcement officers used

tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ad ...

to disperse the crowds. Several days later, on June 25, Van Clarke was arrested for a third time since the start of the protest movement and, per the terms of a 1960 state trespassing law, was held without bail. He was later ordered to either pay a $1,500 fine ($ in 2021) or serve two years in jail.

Williams's arrest and subsequent rioting

On July 8, Williams was arrested and held on bail for $7,500 ($ in 2021). Following his arrest, Bevel, Cotton, and Young took charge of the protests. Ultimately, Williams spent over a month in jail. On July 10, a riot broke out between police officers and about 2,000 protestors who had gathered outside the city jail following the arrest of SNCC Field Secretary Bruce Gordon. During the two-hour fight, police used tear gas and high-powered water hoses to disperse the crowds and beat several protestors with clubs, leading to multiple injuries. The riot resulted in at least one store being burned and saw 75 peopple arrested. Following this, the

Georgia National Guard

The Georgia National Guard is the National Guard of the U.S. state of Georgia, and consists of the Georgia Army National Guard and the Georgia Air National Guard. (The Georgia State Defense Force is the third military unit of the Georgia Depar ...

became mobilized, with Governor

Carl Sanders

Carl Edward Sanders Sr. (May 15, 1925 – November 16, 2014) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 74th Governor of the state of Georgia from 1963 to 1967.

Early life and education

Carl Sanders was born on May 15, 1925 in ...

promising to take "whatever steps necessary" to bring an end to the protests. Additionally, the city government banned marches.

Desegregation agreement reached

Following the rioting, several white business owners in the city intervened on behalf of the protestors and helped to secure his release from jail. Additionally, many businesspeople in the city agreed to negotiate an end to the protests. By this point, the protests had led to a 30 percent total decline in trade in the city. A group of 100 city businessmen, assembled by Mayor Maclean, met and created a plan that would see the desegregation of the city's remaining public and private facilities in exchange for a 60-day suspension of protesting. In addition, the city government would fully rescind all remaining segregation ordinances. This agreement was implemented in August, prompting the NAACP to call off a planned Christmas boycott. On October 1, this desegregation came into effect, affecting, among other institutions, all of the city's

bowling alley

A bowling alley (also known as a bowling center, bowling lounge, bowling arena, or historically bowling club) is a facility where the sport of bowling is played. It can be a dedicated facility or part of another, such as a Meetinghouse, clubhous ...

s, hotels, motels, movie theaters, and swimming pools. The desegregation was so thorough that, during an address given on New Year's Day 1964 at the city's Municipal Auditorium, King praised Savannah as "the most desegregated city south of the

Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virginia ...

".

Aftermath

Analysis by historians

Many historians have noted the uniqueness of the Savannah protest movement for its longevity and overall success. In a 2019 article, the

Georgia Historical Society

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) is a statewide historical society in Georgia. Headquartered in Savannah, Georgia, GHS is one of the oldest historical organizations in the United States. Since 1839, the society has collected, examined, and ta ...

stated, "Although a part of the larger Civil Rights Movement, the Savannah Protest Movement was uncommon, especially in its ability to exert continuous pressure on white power structures over an extended period". Historian Elizabeth Ellis Miller, discussing the protest movement in 2023, said, "Savannah ... became known as a site for peaceful demonstrations and a model for other locales considering taking on sit-ins". Many notable civil rights activists saw their first involvement in the national movement in Savannah, including Van Clarke and

Earl Shinhoster

Earl Theodore Shinhoster (July 5, 1950 – June 11, 2000) was a Black civil rights activist in Savannah, Georgia.

Shinhoster was born in Savannah in 1950 to Nadine and Willie Shinhoster, he was an alumnus of Morehouse College and Cleveland State ...

, and Williams called the 1963 protests the nation's largest outside of Birmingham. The protest is also notable for the level of peace maintained throughout the movement, as opposed to the extreme levels of violence seen in civil rights movements in other cities throughout the American South during this time.