Sarah Maria Cornell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarah Maria Cornell (May 3, 1803 – December 20, 1832) was a

Sarah Maria Cornell (May 3, 1803 – December 20, 1832) was a

On the morning of December 21, 1832, Cornell's body was found by farmer John Durfee quickly identified by the minister. Later discovered among her personal effects at the Hathaway residence was a note written by Cornell and dated the same day as her death:

On the morning of December 21, 1832, Cornell's body was found by farmer John Durfee quickly identified by the minister. Later discovered among her personal effects at the Hathaway residence was a note written by Cornell and dated the same day as her death:

Sarah Maria Cornell (May 3, 1803 – December 20, 1832) was a

Sarah Maria Cornell (May 3, 1803 – December 20, 1832) was a Fall River, Massachusetts

Fall River is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. The City of Fall River's population was 94,000 at the 2020 United States Census, making it the tenth-largest city in the state.

Located along the eastern shore of Mount H ...

, mill worker whose corpse was found hanging from a stackpole on the farm of John Durfee in nearby Tiverton, Rhode Island

Tiverton is a New England town, town in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 16,359 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census.

Geography

Tiverton is located on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, across the Sa ...

on December 21, 1832. Her death was at first thought to be a suicide. After an autopsy, it was discovered she was pregnant. Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

minister Ephraim K. Avery would be suspected of her pregnancy and tried for her murder, in a trial what would engage local industrialists against the New England Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Although Avery would be acquitted for the murder, he was forever scorned in the eyes of the public.Fall River Outrage, David Richard Kasserman, 1986

Biography

Sarah Maria Cornell was born on May 3, 1803, likely inRupert, Vermont

Rupert is a town in Bennington County, Vermont, United States. The population was 698 at the 2020 census.

The town is home tThe Maple News a trade publication focused on the maple syrup industry, and the former Jenks Tavern, built around 1807, ...

to James and Lucretia (Leffingwell) Cornell. Lucretia had been born well-off in an old Puritan family, the daughter of a Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

merchant and paper maker. However she had been disowned by her father after she married James Cornell, who had worked in his paper mill, and of whom he did not approve. James abandoned the family when Cornell was a baby, forcing her mother to give up her older sister and brother to relatives as she was financially unable to care for three children. Cornell remained with her mother to age eleven when she moved in with her aunt Joanna, in Norwich, Connecticut

Norwich ( ) (also called "The Rose of New England") is a city in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The Yantic, Shetucket, and Quinebaug Rivers flow into the city and form its harbor, from which the Thames River flows south to Long ...

. Later in her teens, she apprenticed as a tailor. In 1820 she moved to nearby Bozrahville and worked as a tailor for about two years.

Around 1822 or 1823 she went to work at a cotton mill in Killingly, Connecticut

Killingly is a town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 17,752 at the 2020 census. It consists of the borough of Danielson and the villages of Attawaugan, Ballouville, Dayville, East Killingly, Rogers, and South ...

. In the years that followed, she would move often and work at various mills in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, including stints in North Providence

North Providence is a New England town, town in Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 34,114 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census.

Geography

According to the United States C ...

, Jewett City

Jewett City is a borough in New London County, Connecticut, in the town of Griswold. The population was 3,487 at the 2010 census. The borough was named for Eliezer Jewett, who founded a settlement there in 1771.

Geography

According to the Uni ...

, Slatersville

Slatersville is a village on the Branch River in the town of North Smithfield, Rhode Island, United States. It includes the Slatersville Historic District, a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The historic distr ...

. During this period, Cornell often got into trouble, including charges of theft and other "inappropriate" acts for a woman of that time.

During her time at Slatersville

Slatersville is a village on the Branch River in the town of North Smithfield, Rhode Island, United States. It includes the Slatersville Historic District, a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The historic distr ...

between 1823 and 1826, Cornell converted to Methodism, and sought to change her ways. However, in February 1826, the mill at Slatersville burned to the ground and she was forced to seek employment elsewhere. She first moved to the nearby village of Branch Factory and later to Mendon Mills (later called Millville, Massachusetts

Millville is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 3,174 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. It is part of the Providence metropolitan area.

History

Millville w ...

), several miles away.

In early 1827, Cornell moved again to find mill work in Dedham, Massachusetts

Dedham ( ) is a town in and the county seat of Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 25,364 at the 2020 census. It is located on Boston's southwest border. On the northwest it is bordered by Needham, on the southwest b ...

. However, after only a few weeks there she moved again to Dorchester, Massachusetts

Dorchester (colloquially referred to as Dot) is a Boston neighborhood comprising more than in the City of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Originally, Dorchester was a separate town, founded by Puritans who emigrated in 1630 from Dorchester ...

, where she was able to reconnect with the Methodists. In May 1828, she moved to the booming mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020, it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as of ...

where she worked as a weaver until about the end of 1829. It was during this period in Lowell that she met a newly arrived Methodist minister, Ephraim Kingsbury Avery

Ephraim Kingsbury Avery (December 18, 1799 – October 23, 1869) was a Methodist minister who was among the first clergymen tried for murder in the United States. Avery is often cited as "the first", although it is thought there is at least Ev ...

.

In September 1830, she moved to Dover, New Hampshire

Dover is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 32,741 at the 2020 census, making it the largest city in the New Hampshire Seacoast region and the fifth largest municipality in the state. It is the county se ...

. Only two months later she moved again to Somersworth, New Hampshire

Somersworth is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 11,855 at the 2020 census. Somersworth has the smallest area and third-lowest population of New Hampshire's 13 cities.

History

Somersworth, originally ca ...

. During the summer of 1831 she left New Hampshire for Waltham, Massachusetts

Waltham ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, and was an early center for the labor movement as well as a major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. The original home of the Boston Manufacturing Company, th ...

but only stayed there a few weeks. She then moved to Taunton, Massachusetts

Taunton is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Bristol County. Taunton is situated on the Taunton River which winds its way through the city on its way to Mount ...

where she found employment. In May 1832 she left Taunton for Woodstock, Connecticut

Woodstock is a town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 8,221 at the 2020 census.

History

17th century

In the mid-17th century, John Eliot, a Puritan missionary to the Native Americans, established "praying town ...

where she was able to find work again as a tailor in Grindall Rawson's shop. It was at a Methodist Camp Meeting in Thompson, Connecticut

Thompson is a town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The town was named after Sir Robert Thompson, an English landholder. The population was 9,189 at the 2020 census. Thompson is located in the northeastern corner of the state and i ...

at the end of August 1832 that Cornell once again crossed paths with Reverend Avery. By this time, Avery had become the minister in Bristol, Rhode Island

Bristol is a town in Bristol County, Rhode Island, US as well as the historic county seat. The town is built on the traditional territories of the Pokanoket Wampanoag. It is a deep water seaport named after Bristol, England.

The population of B ...

. It is alleged that during the Thompson Camp meeting that Avery seduced Sarah Cornell.

In October 1832, she moved to Fall River

Fall River is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. The City of Fall River's population was 94,000 at the 2020 United States Census, making it the tenth-largest city in the state.

Located along the eastern shore of Mount H ...

where she found lodging at the home of Elija Cole. By this time she was showing clear signs of pregnancy, and sought advice from a local doctor in Fall River. By early December 1832, she moved to the Hathaway residence on Spring Street.

Death

On the morning of December 21, 1832, Cornell's body was found by farmer John Durfee quickly identified by the minister. Later discovered among her personal effects at the Hathaway residence was a note written by Cornell and dated the same day as her death:

On the morning of December 21, 1832, Cornell's body was found by farmer John Durfee quickly identified by the minister. Later discovered among her personal effects at the Hathaway residence was a note written by Cornell and dated the same day as her death:

"If I should be missing, enquire of the Rev. Mr. Avery ofOther suspicious and incriminating letters were also discovered, as well as a conversation she had had with a doctor indicating the married Avery was the father of her unborn child. ABristol Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ..., he will know where I am."

coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

's jury was convened in Tiverton before any autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

had been performed. This jury found that Cornell had "committed suicide by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

herself upon a stake ... and was influenced to commit said crime by the wicked conduct of a married man."

After the autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

was performed, it was discovered that Cornell had been four months pregnant at the time of her death. A second coroner's jury was convened, this time in Bristol, Rhode Island

Bristol is a town in Bristol County, Rhode Island, US as well as the historic county seat. The town is built on the traditional territories of the Pokanoket Wampanoag. It is a deep water seaport named after Bristol, England.

The population of B ...

. This jury overruled the earlier finding of suicide and accused Ephraim Kingsbury Avery, a married Methodist minister, as the " principal or accessory" in her death. Avery was quickly arrested on a charge of murder, but just as quickly set free on his own recognizance

In some common law nations, a recognizance is a conditional pledge of money undertaken by a person before a court which, if the person defaults, the person or their sureties will forfeit that sum. It is an obligation of record, entered into before ...

.

Cornell's pregnancy led another Methodist minister to reject the responsibility of burying her the second time (she already once been exhumed for autopsy). He claimed that she had only been a "probationary" member of his congregation. Responsibility for her burial was assumed by the Fall River Congregationalists, and Cornell was buried as an indigent

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little , on Christmas Eve. That night, in

The trial began in

The trial began in

Fall River

Fall River is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. The City of Fall River's population was 94,000 at the 2020 United States Census, making it the tenth-largest city in the state.

Located along the eastern shore of Mount H ...

, money was raised and two committees pledged to assist the officials of Tiverton with the murder investigation. The next day, a steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

was charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

ed to take one hundred men from Fall River to Bristol. They surrounded Avery's home and demanded he come out. Avery declined, but did send a friend outside to try to placate the crowd. The men eventually left when the steamship signaled its return to Fall River.

In Bristol, an inquest was convened, in which two Justices of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

found there to be insufficient evidence to try Avery for the crime of murder. The people of Fall River were outraged, and there were rumors that one of the justices was a Methodist, and was looking to quell the scandal. The deputy sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

of Fall River, Harvey Harnden, obtained from a Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

superior court

In common law systems, a superior court is a court of general jurisdiction over civil and criminal legal cases. A superior court is "superior" in relation to a court with limited jurisdiction (see small claims court), which is restricted to civil ...

judge a warrant for Avery's arrest. When a Rhode Island sheriff went to serve it, he discovered that Avery had already fled.

On January 20, 1833, Harnden tracked Avery to Rindge, New Hampshire

Rindge is a town in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 6,476 at the 2020 census, up from 6,014 at the 2010 census. Rindge is home to Franklin Pierce University, the Cathedral of the Pines and part of Annett State ...

. Avery later claimed he had fled because he feared for his life, particularly at the hands of the mob that had surrounded his house. Harnden extradited

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdict ...

Avery to Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

, where Avery was put in jail. On March 8, 1833, Avery was indicted

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of an ...

for murder by a Newport County grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

. He pleaded "not guilty".

Trial

The trial began in

The trial began in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

on May 6, 1833, and was heard by the Supreme Judicial Council. The lawyers for the prosecution were Rhode Island Attorney General

The Attorney General of Rhode Island is the chief legal advisor of the Government of the State of Rhode Island and oversees the State of Rhode Island Department of Law. The attorney general is elected every four years. The current Attorney Gene ...

Albert C. Greene

Albert Collins Greene (April 15, 1792January 8, 1863) was an American lawyer and politician from Rhode Island. He served as a United States senator and Attorney General of Rhode Island.

Early life

Greene was born in East Greenwich, Rhode Isl ...

and former attorney general Dutee Jerauld Pearce

Dutee Jerauld Pearce (April 3, 1789 – May 9, 1849) was an American politician and a United States Representative from Rhode Island.

Early life

Born on Prudence Island, Pearce graduated from Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island in 1808, ...

. The six lawyers for the defense, hired by the Methodist Church

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

, were led by former United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

and New Hampshire Attorney General

The Attorney General of New Hampshire is a constitutional officer of the U.S. state of New Hampshire who serves as head of the New Hampshire Department of Justice. , the state's attorney general is John Formella.

Qualifications and appointment

Un ...

Jeremiah Mason

Jeremiah Mason (April 27, 1768 – October 14, 1848) was a United States senator from New Hampshire.

Early life

Mason was born in Lebanon, Connecticut on April 27, 1768. He was a son of Jeremiah Mason (1729/30–1813) and the former Elizabet ...

.

The trial lasted 27 days. Under Rhode Island law at the time, defendant

In court proceedings, a defendant is a person or object who is the party either accused of committing a crime in criminal prosecution or against whom some type of civil relief is being sought in a civil case.

Terminology varies from one jurisdic ...

s in capital cases were not permitted to offer testimony in their own defense, so Avery did not get the opportunity to speak. However, both the prosecution and the defense called a large number of witnesses to testify, 68 for the prosecution, and 128 for the defense.

Although the defense maintained that Avery had not been present when the murder occurred, the larger part of the defense strategy was to call into question Cornell's morals. The defense characterized her as "utterly abandoned, unprincipled, profligate," and brought forth many witnesses to testify to her promiscuity

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different Sexual partner, partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as pro ...

, suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, means having thoughts, ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of ending one's own life.World Health Organization, ''ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics'', ver. 09/2020MB26.A Suicidal ideatio ...

and mental instability. Much was made of how Cornell had been cast out of the Methodist Church

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

for fornication

Fornication is generally consensual sexual intercourse between two people not married to each other. When one or more of the partners having consensual sexual intercourse is married to another person, it is called adultery. Nonetheless, John ...

.

The prosecution largely attempted to portray the Methodist clergy as a dangerous, almost secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

, willing to defend their minister and the good name of their church at any cost.

A medical debate centered around whether the unborn child was in fact conceived in August, although Puritan standards of propriety regarding the female body sometimes made it difficult to elicit factual information. One female witness, when questioned as to the state of Cornell's body, absolutely refused to answer, saying, "I never heard such questions asked of nobody."

On June 2, 1833, after deliberating for 16 hours, the jury found Ephraim Kingsbury Avery "not guilty". The minister was set free and returned to his position in the Methodist Church

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

, but the public opinion

Public opinion is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to a society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

Etymology

The term "public opinion" was derived from the French ', which was first use ...

was that Avery had been wrongfully acquitted

In common law jurisdictions, an acquittal certifies that the accused is free from the charge of an offense, as far as criminal law is concerned. The finality of an acquittal is dependent on the jurisdiction. In some countries, such as the ...

. Rallies hanged or burned effigies

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

of Avery, and he himself was once almost lynched in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. A great deal of anger was also directed at the Methodist Church. To ease tensions, the church's New England Conference convened a trial of its own, chaired by Wilbur Fisk

Willbur Fisk (August 31, 1792February 22, 1839) was a prominent American Methodist minister, educator and theologian. He was the first President of Wesleyan University.

Family background

Fisk was born in Guilford, (near Brattleboro), Vermont on A ...

, in which Avery was again acquitted. This did little, if anything, to quell public antipathy toward Avery or the church.

Avery later embarked on a speaking tour to vindicate himself in the eyes of the public, but his efforts were largely unsuccessful. In 1836, Avery left the Methodist ministry, and took his family first to Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, then upstate New York. They ultimately settled in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, where he lived out the rest of his days as a farmer. Avery also wrote a pamphlet called ''The correct, full and impartial report of the trial of Rev. Ephraim K. Avery''. He died on October 23, 1869.

Legacy

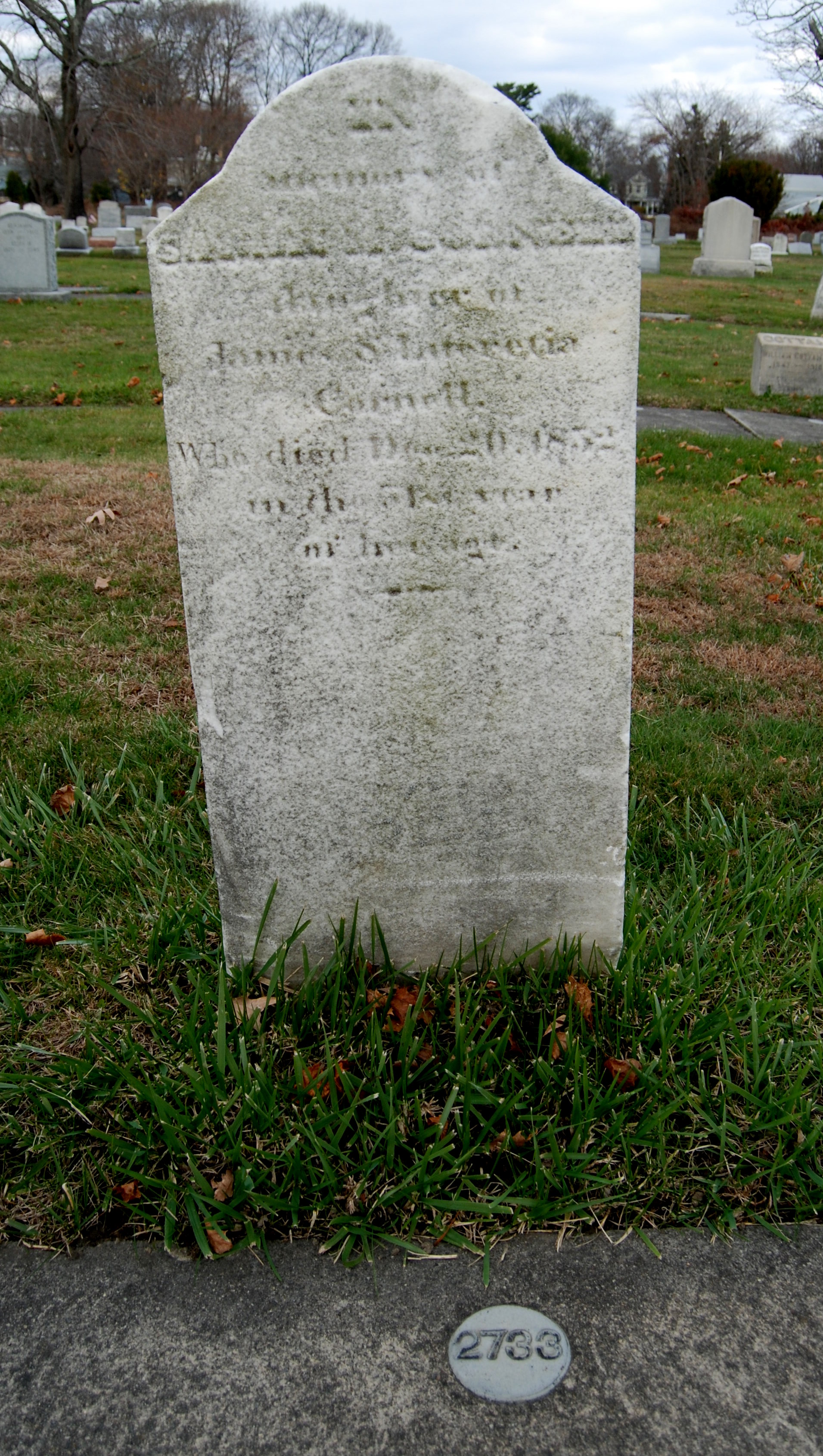

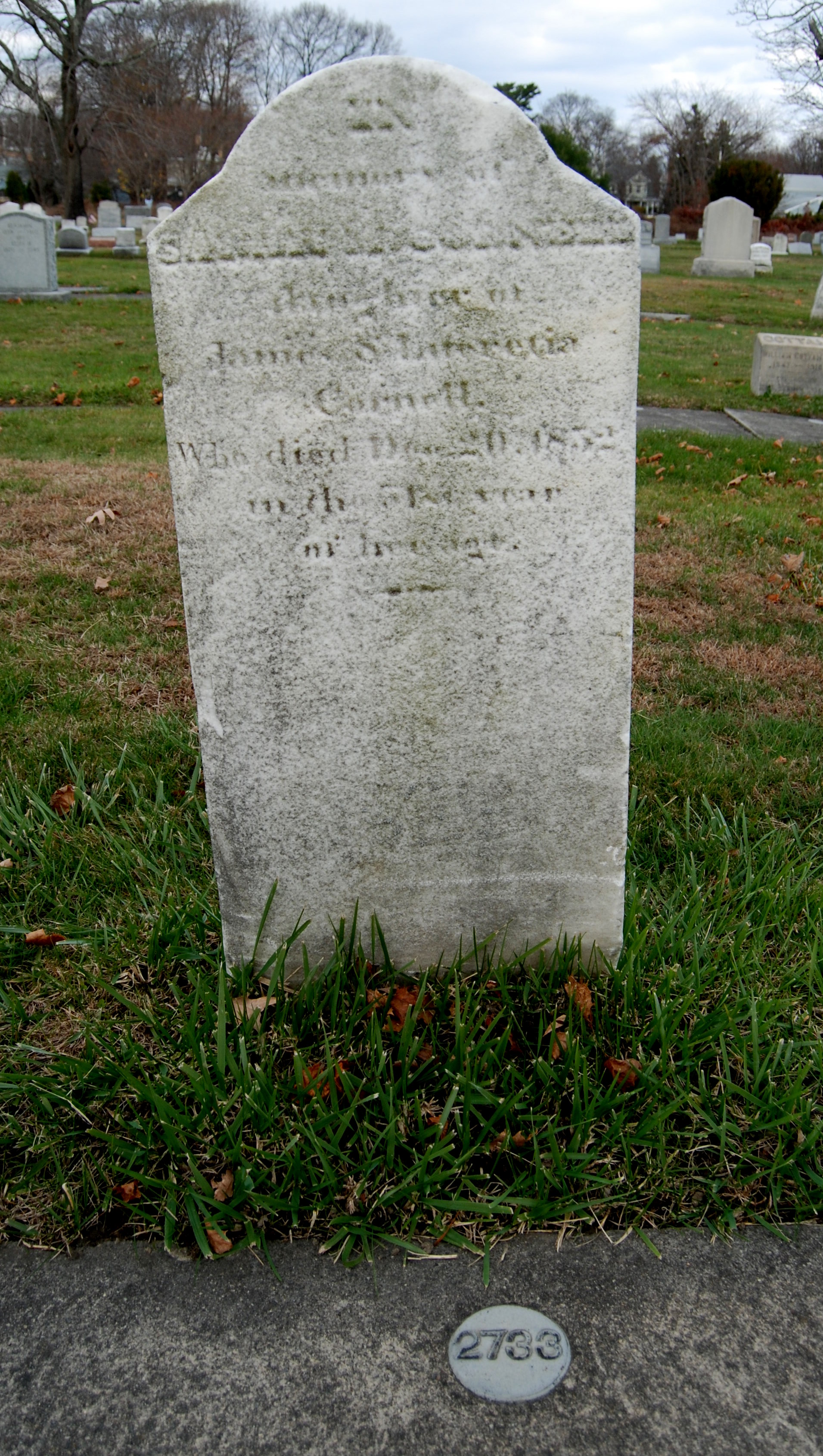

Cornell's body was originally buried on the farm near where her body was found. However, years later it was moved to Plot 2733 on Whitethorn Path atOak Grove Cemetery (Fall River, Massachusetts)

Oak Grove Cemetery is a historic cemetery located at 765 Prospect Street in Fall River, Massachusetts. It was established in 1855 and greatly improved upon in the years that followed. It features Gothic Revival elements, including an elaborate e ...

when the farm became South Park

''South Park'' is an American animated sitcom created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone and developed by Brian Graden for Comedy Central. The series revolves around four boys Stan Marsh, Kyle Broflovski, Eric Cartman, and Kenny McCormickand th ...

.

References

Further reading

Raven, Rory (2009). Wicked Conduct: The Minister, the Mill Girl, and the Murder That Captivated Old Rhode Island. Charleston, SC: istory Press pp. 128. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Cornell, Sarah Maria 1803 births 1832 deaths People from Fall River, Massachusetts People from Worcester County, Massachusetts People from Rupert, Vermont People from North Smithfield, Rhode Island Cornell family Deaths by hanging