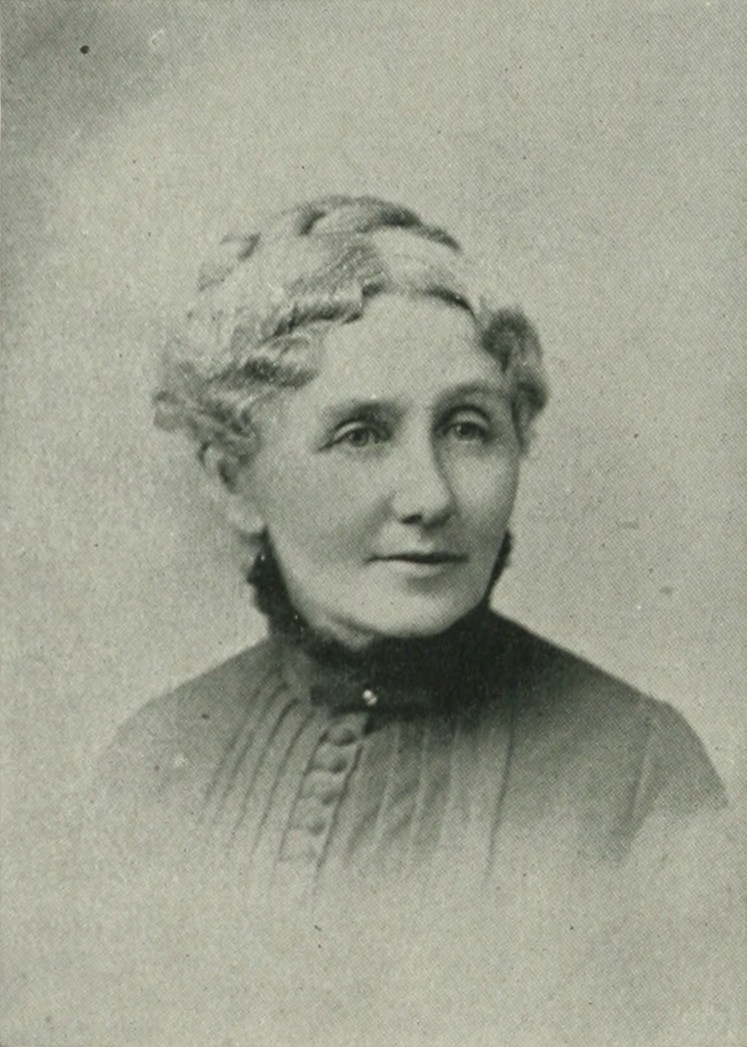

Sarah Brown Ingersoll Cooper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarah Brown Ingersoll Cooper (December 12, 1835 – December 11, 1896) was an American educator, author, evangelist, philanthropist, and civic

activist. She is remember as a religious teacher and her efforts to increase the wide interest in

In 1882, Mrs. Leland Stanford, who had been an active helper in the work from the very first, dedicated a large sum for the establishment of free kindergartens, in San Francisco and in adjacent towns, in memory of her son. Then other memorial kindergartens were endowed. By 1892, 32 kindergartens were under the care of Mrs. Cooper and her daughter, Harriet. Over was donated to Mrs. Cooper to carry on this work in San Francisco, and over 10,000 children were trained in these schools. Her notable and historical trial for heresy in 1881 made her famous as a religious teacher and did much to increase the wide interest in her kindergarten work. Mrs. Cooper is a philanthropist and devotes all her time to benevolent work.

Cooper served as a director of the Associated Charities, vice-president of the

In 1882, Mrs. Leland Stanford, who had been an active helper in the work from the very first, dedicated a large sum for the establishment of free kindergartens, in San Francisco and in adjacent towns, in memory of her son. Then other memorial kindergartens were endowed. By 1892, 32 kindergartens were under the care of Mrs. Cooper and her daughter, Harriet. Over was donated to Mrs. Cooper to carry on this work in San Francisco, and over 10,000 children were trained in these schools. Her notable and historical trial for heresy in 1881 made her famous as a religious teacher and did much to increase the wide interest in her kindergarten work. Mrs. Cooper is a philanthropist and devotes all her time to benevolent work.

Cooper served as a director of the Associated Charities, vice-president of the

"A Pacific Heretic"

Cooper's trial (''Unity'', vol. 7–8, pp. 349–50) {{DEFAULTSORT:Cooper, Sarah Brown Ingersoll 1835 births 1896 deaths Philanthropists from New York (state) American suffragists Cazenovia College alumni Deaths from asphyxiation Emma Willard School alumni Activists from Syracuse, New York People from Cazenovia, New York 19th-century American philanthropists Wikipedia articles incorporating text from A Woman of the Century Early childhood education in the United States Clubwomen American letter writers Founders of schools in the United States Women founders Educators from California 19th-century American women educators 19th-century American educators 19th-century American women writers Heresy in Christianity American essayists Woman's Christian Temperance Union people Pacific Coast Women's Press Association

kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cent ...

work. Cooper served as first president of the International Kindergarten Union, president of the National Kindergarten Union, president and vice-president of the Woman's Press Association, president of the Woman's Suffrage Association, and president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. She served as vice-president of the Century Club, treasurer of the World's Federation of Woman's Clubs, a director of the Associated Charities, and one of the five women elected to the Pan-Republican Congress. At the 1893 World's Fair, she delivered thirty-six addresses, and on her return, helped to organize the Woman's Congress of which she was president for two years and at the time of her death. Several years before her death, Mrs. Cooper became a convert to equal suffrage and was president of the Amendment Campaign Committee. A few months before she died, Cooper stated that she was an officer of nineteen societies for charitable purposes.

She dealt with a voluminous correspondence. The assertion was made that the letters which she answered in the year before she died numbered 11,000. She wrote extensively on topics related to women, children, and education.

Early life and education

Sarah Brown Ingersoll was born inCazenovia, New York

Cazenovia is an incorporated Administrative divisions of New York#Town, town in Madison County, New York. The population was 6,740 at the time of the 2020 census. The town is named after Theophilus Cazenove , Theophile Cazenove, the ''Agent Gener ...

, December 12, 1835. She had two younger sisters who became Mrs. J. A. Skilton and Mrs. Reese M. Rawlings. Her mother died when she was a little child, and she was adopted by her great-aunt, over 70 years of age. Col. Robert G. Ingersoll

Robert Green Ingersoll (; August 11, 1833 – July 21, 1899), nicknamed "the Great Agnostic", was an American lawyer, writer, and orator during the Golden Age of Free Thought, who campaigned in defense of agnosticism.

Personal life

Robert Inge ...

was a cousin.

When twelve years old, she appeared in print in the village paper, the ''Madison County Whig'', and from that time, she was more or less engaged in literary work on papers and magazines. When but fourteen years of age, she opened a Sunday-school class in Eagle Village, from Cazenovia, and that class was the start of what became a church congregation. When she started the school, some of the committeemen came to her and told her that, while they believed her to be qualified in every way to teach, at the same time they would all like it better if she would go home and lengthen her skirts.

She was graduated from the Cazenovia Seminary in 1853, the first coeducational institution in the U.S., and numbering among its graduates Leland Stanford, Phillip Armour, and Charles Dudley Warner—all lifelong friends of Mrs. Cooper. She subsequently attended the Troy Female Seminary

The Emma Willard School, originally called Troy Female Seminary and often referred to simply as Emma, is an independent university-preparatory day and boarding school for young women, located in Troy, New York, on Mount Ida, offering grades 9– ...

, of which Frances Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1879 an ...

was principal, studying music and modern languages.

Career

After her graduation from college, she went toAugusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

, as a governess in the family of Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

William Schley

William Schley (December 15, 1786 – November 20, 1858) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician.

Biography

Schley was born on December 15 (some sources say December 10), 1786 in Frederick, Maryland, the original locus and domicile of t ...

. On the Governor's plantation, there were 500 or more slaves, and Cooper (then Miss Ingersoll), used to gather them about her to teach them the Scriptures.

While in Augusta, in 1855, she married Halsey Fenimore Cooper, also a Cazenovia Seminary graduate, who had been appointed by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

to the office of surveyor and inspector of the port of Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

. They also worked as editors on ''The Advertiser'', with Mrs. Cooper assisting Mr. Cooper. They had two daughters, Harriet ("Hattie") (b. 1856) and Mollie (b. 1861), as well as two sons, who died while still babies.

Being abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, the Coopers went north at the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. They settled briefly in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, then moved to Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

in 1863, where Mr. Cooper was appointed assessor of internal revenue. There, Mrs. Cooper was elected president of the Society for the Aid of Refugees. She taught a large Bible class, which comprised from 100 to 300 soldiers. In 1864, after Mollie died, Mrs. Cooper began to suffer from depression and illness. For two years, she attempted to recuperate in Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County, Minnesota, Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississip ...

. She recovered when the family moved to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in 1869, where Mr. Cooper worked for the IRS

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory tax ...

. She became a staff member of the ''Overland Monthly

The ''Overland Monthly'' was a monthly literary and cultural magazine, based in California, United States. It was founded in 1868 and published between the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

History

The '' ...

'', workinging as a proof-reader, essayist, and book reviewer. She also penned articles for the religious press, and researched and wrote field reports regarding education in California for the U.S. government in Washington, D.C.

Her first Bible class in San Francisco was in the Howard Presbyterian Church, where Dr. Scudder was filling the pulpit. From there, she went to the Calvary Presbyterian Church. It was there that Mrs. Cooper was tried for heresy, because she could not conscientiously subscribe to the doctrines of infant damnation or everlasting punishment. Mrs. Cooper was welcomed to the First Congregational Church, where she afterward remained.

Still later, opened the class in the First Congregational Church. That class numbered over 300 members and embraced persons representing many religious sects, including the Jewish and the Roman Catholic faiths. While the credit of establishing the first free kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cent ...

in San Francisco is due to Prof. Felix Adler and a few of his friends, yet the credit of the extraordinary growth of the work is almost entirely due to Mrs. Cooper, who paid a visit to the Silver street free kindergarten in November, 1878, and from that moment became the leader of the kindergarten work and the friend of the training school for kindergarten teachers.

The rapid growth of the free kindergarten system in California had its first impulse in six articles written by Mrs. Cooper for the ''San Francisco Bulletin'' in 1879. The first of these was entitled "The Kindergarten, a Remedy for Hoodlumism," and was of vital interest to the public, for just at that time, ruffianism was so terrific, that a vigilance committee was organized to protect the citizens. The second article was "The History of the Silver Street Free Kindergarten." That aroused immediate interest among philanthropic people. In the early part of 1878, there was not a free Kindergarten on the western side of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

; by 1892, there were 65 in San Francisco, and several others in progress of organization. Outside of San Francisco, they extended from the extreme northern part of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

to Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, and they formed in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

, and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

, and in almost every large city and town in California. Mrs. Cooper attributed the rapid strides in that work in San Francisco to the fact that wealthy persons, induced to study the work for themselves, became convinced of its permanent and essential value to the State. The second free kindergarten in San Francisco was opened under the auspices of Cooper's Bible class, in October, 1879. She founded the "Jackson Street Kindergarten Association" in 1879.

In 1882, Mrs. Leland Stanford, who had been an active helper in the work from the very first, dedicated a large sum for the establishment of free kindergartens, in San Francisco and in adjacent towns, in memory of her son. Then other memorial kindergartens were endowed. By 1892, 32 kindergartens were under the care of Mrs. Cooper and her daughter, Harriet. Over was donated to Mrs. Cooper to carry on this work in San Francisco, and over 10,000 children were trained in these schools. Her notable and historical trial for heresy in 1881 made her famous as a religious teacher and did much to increase the wide interest in her kindergarten work. Mrs. Cooper is a philanthropist and devotes all her time to benevolent work.

Cooper served as a director of the Associated Charities, vice-president of the

In 1882, Mrs. Leland Stanford, who had been an active helper in the work from the very first, dedicated a large sum for the establishment of free kindergartens, in San Francisco and in adjacent towns, in memory of her son. Then other memorial kindergartens were endowed. By 1892, 32 kindergartens were under the care of Mrs. Cooper and her daughter, Harriet. Over was donated to Mrs. Cooper to carry on this work in San Francisco, and over 10,000 children were trained in these schools. Her notable and historical trial for heresy in 1881 made her famous as a religious teacher and did much to increase the wide interest in her kindergarten work. Mrs. Cooper is a philanthropist and devotes all her time to benevolent work.

Cooper served as a director of the Associated Charities, vice-president of the Pacific Coast Women's Press Association

Pacific Coast Women's Press Association (PCWPA; September 27, 1890 - 1941) was a press organization for women located on the West Coast of the United States. Discussions were not permitted regarding politics, religion, or reform. The members of the ...

, member of the Century Club and the leader of one of the largest Bible classes in the United States. Considered to be one of the best-known and best-loved women on the Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the Pac ...

, she was elected a member of the Pan-Republic Kindergarten Congress of 1893, one of five women of the world who had that distinguished honor, along with Mary Simmerson Cunningham Logan

Mary Simmerson Cunningham Logan (née Mary Simmerson Cunningham; pen name, Mrs. John A. Logan; August 15, 1838February 22, 1923) was an American writer and editor from Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States ...

, Mary Virginia Ellet Cabell, president of the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

, Frances Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1879 an ...

, and Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

, of the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desi ...

. She was also a speaker while at the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

(Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, 1893).

She was elected treasurer of the World's Federation of Women's Clubs in 1894. In 1895, she served as president of the National Kindergarten Union. She was the first president of the International Kindergarten Union.

Personal life

In 1879, Halsey lost his job as Deputy Surveyor and the family suffered financial difficulties. As a result of the strain, he committed suicide in 1885. After attempting to clear her husband's name, Sarah continued her philanthropic career. She taught both the Bible School and Kindergarten, and was involved with women's rights groups. Her daughter, Harriet had quit her teaching job to assist Sarah, but suffered from bouts of depression, especially following the death of her father. Harrietasphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that can i ...

ted her mother and herself on December 11, 1896, by turning on the gas, with suicidal intent, after her mother had fallen asleep.

Notes

References

Attribution

* * * *Bibliography

* * *External links

*"A Pacific Heretic"

Cooper's trial (''Unity'', vol. 7–8, pp. 349–50) {{DEFAULTSORT:Cooper, Sarah Brown Ingersoll 1835 births 1896 deaths Philanthropists from New York (state) American suffragists Cazenovia College alumni Deaths from asphyxiation Emma Willard School alumni Activists from Syracuse, New York People from Cazenovia, New York 19th-century American philanthropists Wikipedia articles incorporating text from A Woman of the Century Early childhood education in the United States Clubwomen American letter writers Founders of schools in the United States Women founders Educators from California 19th-century American women educators 19th-century American educators 19th-century American women writers Heresy in Christianity American essayists Woman's Christian Temperance Union people Pacific Coast Women's Press Association