Samuel Abraham Goudsmit on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Abraham Goudsmit (July 11, 1902 – December 4, 1978) was a Dutch-American physicist famous for jointly proposing the concept of electron spin with George Eugene Uhlenbeck in 1925.

Goudsmit studied

Goudsmit studied  Alsos, part of the

Alsos, part of the  After the war he was briefly a professor at

After the war he was briefly a professor at

Samuel A. Goudsmit Papers

the Niels Bohr Library & Archive, American Institute of Physics

Annotated Bibliography for Samuel Abraham Goudsmit from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

of digitized materials related to Goudsmit's and

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goudsmit, Samuel Abraham 20th-century Dutch physicists 1902 births 1978 deaths Manhattan Project people Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Brookhaven National Laboratory staff Leiden University alumni University of Michigan faculty Operation Alsos American people of Dutch-Jewish descent Dutch emigrants to the United States Dutch Jews Jewish American scientists Winners of the Max Planck Medal Jewish physicists Scientists from The Hague Scientists from Michigan 20th-century American physicists 20th-century American Jews Fellows of the American Physical Society

Life and career

Goudsmit was born inThe Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

, Netherlands, of Dutch Jewish descent. He was the son of Isaac Goudsmit, a manufacturer of water-closets, and Marianne Goudsmit-Gompers, who ran a millinery shop. In 1943, his parents were deported to a concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

by the German occupiers of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and were murdered there.

Goudsmit studied

Goudsmit studied physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

at the University of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of L ...

under Paul Ehrenfest, where he obtained his PhD in 1927. After receiving his PhD, Goudsmit served as a Professor at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

between 1927 and 1946. In 1930 he co-authored a text with Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

titled ''The Structure of Line Spectra.''

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

he worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern t ...

. As scientific head of the Alsos Mission, he successfully reached a German group of nuclear physicists around Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent series ...

and Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

at Hechingen

Hechingen ( Swabian: ''Hächenga'') is a town in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated about south of the state capital of Stuttgart and north of Lake Constance and the Swiss border.

Geography

The town lies at the foot of t ...

(then French zone) in advance of French physicist Yves Rocard, who had previously succeeded in recruiting German scientists to come to France.

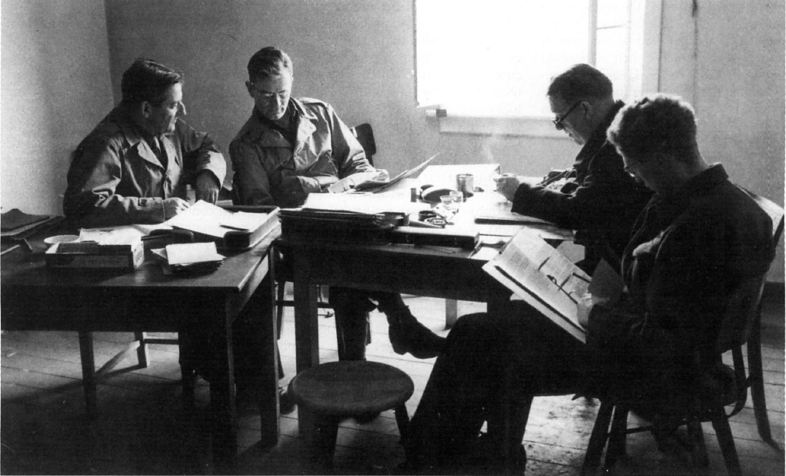

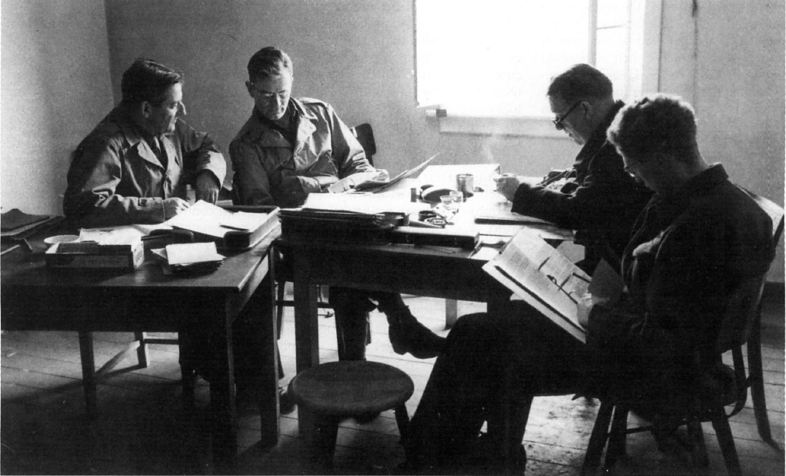

Alsos, part of the

Alsos, part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, was designed to assess the progress of the Nazi atomic bomb project. In the book ''Alsos,'' published in 1947, Goudsmit concludes that the Germans did not get close to creating a weapon. He attributed this to the inability of science to function under a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

state and to Nazi scientists' lack of understanding of how to engineer an atomic bomb. Both of these conclusions have been disputed by later historians (see Heisenberg) and contradicted by the fact that the totalitarian Soviet state produced the bomb shortly after the book's release.

After the war he was briefly a professor at

After the war he was briefly a professor at Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Chart ...

, and from 1948 to 1970 was a senior scientist at the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, Long Island, and was formally established in 1947 at the site of Camp Upton, a former U.S. Army base and Japanese internment c ...

, chairing the Physics Department 1952–1960. He meanwhile became well known as editor-in-chief of the leading physics journal ''Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the American Physical Soc ...

'', published by the American Physical Society. In July 1958 he started the journal ''Physical Review Letters

''Physical Review Letters'' (''PRL''), established in 1958, is a peer-reviewed, scientific journal that is published 52 times per year by the American Physical Society. As also confirmed by various measurement standards, which include the '' Jou ...

'', which offers short notes with attendant brief delays. On his retirement as editor in 1974, Goudsmit moved to the faculty of the University of Nevada in Reno, where he remained until his death four years later.

He also made some scholarly contributions to Egyptology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious ...

published in ''Expedition'', Summer 1972, pp. 13–16 ; ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 78, 1974 p. 78; and ''Journal of Near Eastern Studies'' 40, 1981 pp. 43–46. The Samuel A. Goudsmit Collection of Egyptian Antiquities resides at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology is a museum of archaeology located on the University of Michigan central campus in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the United States. The museum is a unit of the University of Michigan's College of Literature, Science, a ...

at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Goudsmit became a corresponding member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

in 1939, though he resigned the next year. He was readmitted in 1950.

Marriages and children

Goudsmit married his first wife, Jaantje Logher, in 1927. They divorced in 1960, and in the same year Goudsmit married Irene Bejach. Like Goudsmit's parents, Irene's father, a German medical doctor and Berlin public health official, Curt Dietrich Bejach, had been murdered by the Nazis. He perished at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Irene and her sister, Helga, leftGermany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

for the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

as children shortly prior to the outbreak of World War II. They were evacuated as part of the Kindertransport

The ''Kindertransport'' (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second Worl ...

programme, and lived for seven years in the Attenborough family home.

Goudsmit and his first wife had a daughter, Esther Marianne.

Works

* * *References

External links

*ThSamuel A. Goudsmit Papers

the Niels Bohr Library & Archive, American Institute of Physics

Annotated Bibliography for Samuel Abraham Goudsmit from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

of digitized materials related to Goudsmit's and

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

's structural chemistry research.National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goudsmit, Samuel Abraham 20th-century Dutch physicists 1902 births 1978 deaths Manhattan Project people Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Brookhaven National Laboratory staff Leiden University alumni University of Michigan faculty Operation Alsos American people of Dutch-Jewish descent Dutch emigrants to the United States Dutch Jews Jewish American scientists Winners of the Max Planck Medal Jewish physicists Scientists from The Hague Scientists from Michigan 20th-century American physicists 20th-century American Jews Fellows of the American Physical Society