Samizdat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of

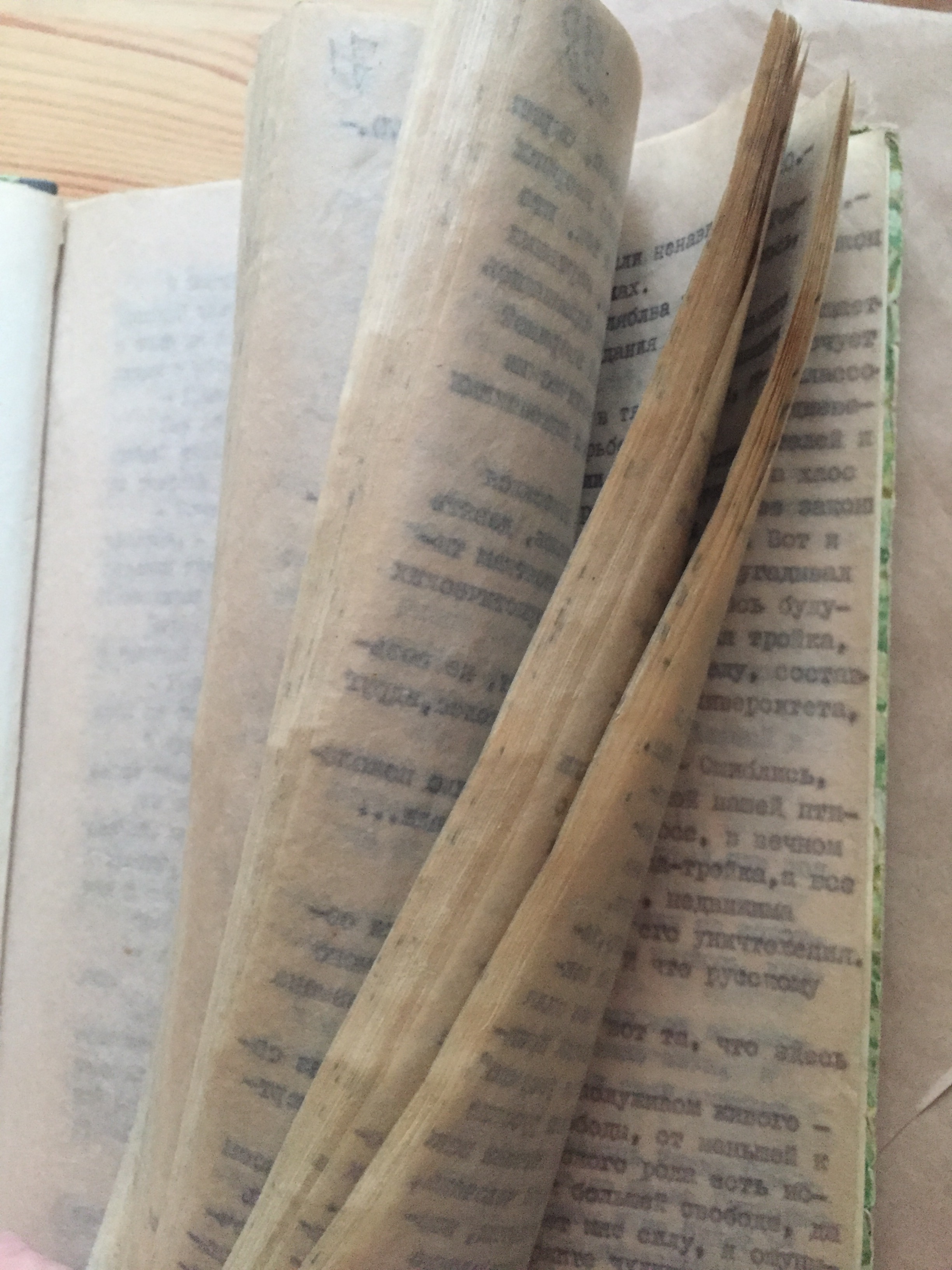

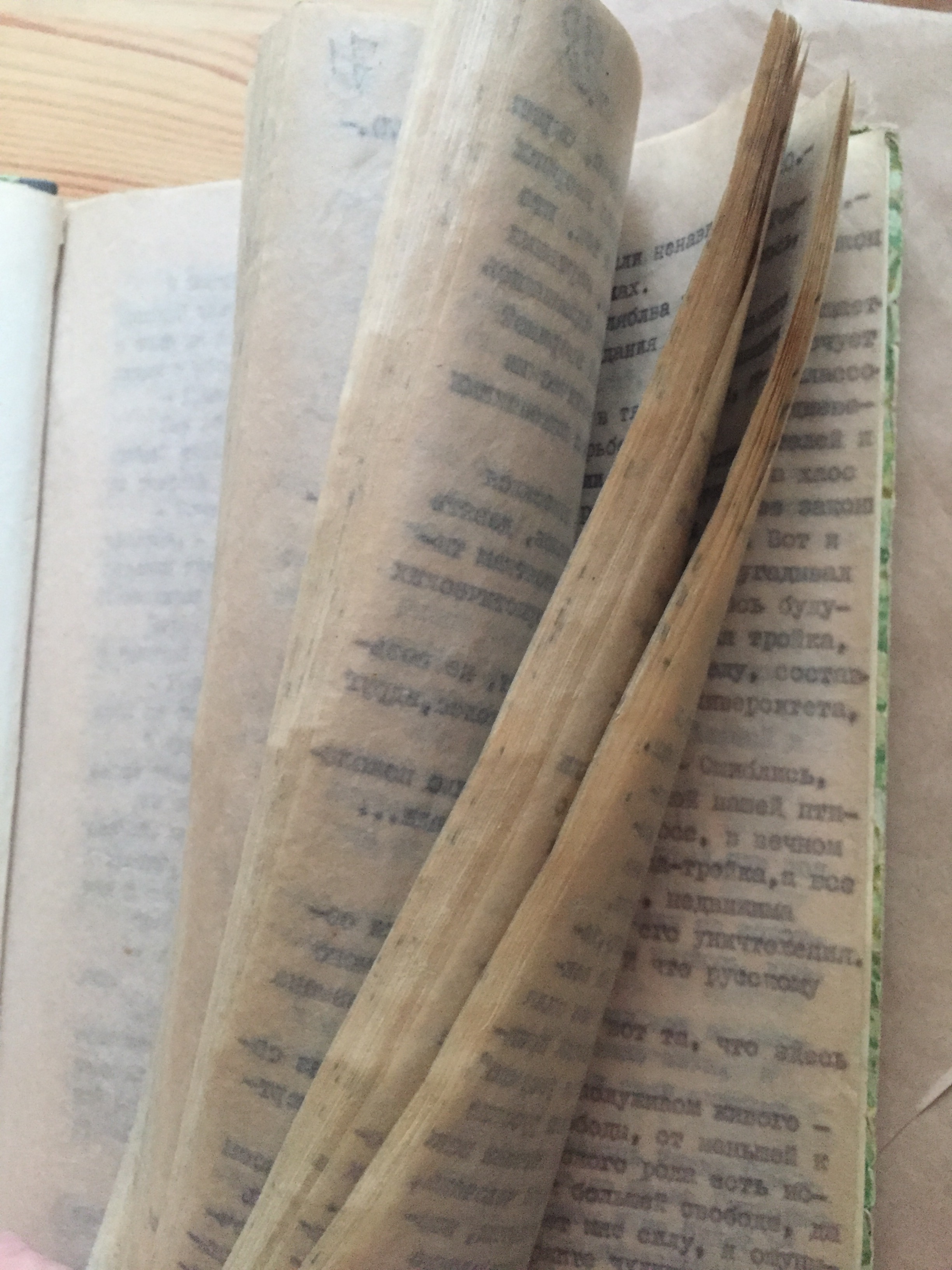

Samizdat distinguishes itself not only by the ideas and debates that it helped spread to a wider audience but also by its physical form. The hand-typed, often blurry and wrinkled pages with numerous typographical errors and nondescript covers helped to separate and elevate Russian samizdat from Western literature. The physical form of samizdat arose from a simple lack of resources and the necessity to be inconspicuous. In time, dissidents in the USSR began to admire these qualities for their own sake, the ragged appearance of samizdat contrasting sharply with the smooth, well-produced appearance of texts passed by the censor's office for publication by the State. The form samizdat took gained precedence over the ideas it expressed, and became a potent symbol of the resourcefulness and rebellious spirit of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union. In effect, the physical form of samizdat itself elevated the reading of samizdat to a prized clandestine act.

Samizdat distinguishes itself not only by the ideas and debates that it helped spread to a wider audience but also by its physical form. The hand-typed, often blurry and wrinkled pages with numerous typographical errors and nondescript covers helped to separate and elevate Russian samizdat from Western literature. The physical form of samizdat arose from a simple lack of resources and the necessity to be inconspicuous. In time, dissidents in the USSR began to admire these qualities for their own sake, the ragged appearance of samizdat contrasting sharply with the smooth, well-produced appearance of texts passed by the censor's office for publication by the State. The form samizdat took gained precedence over the ideas it expressed, and became a potent symbol of the resourcefulness and rebellious spirit of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union. In effect, the physical form of samizdat itself elevated the reading of samizdat to a prized clandestine act.

Samizdat originated from the dissident movement of the Russian

Samizdat originated from the dissident movement of the Russian

The earliest samizdat periodicals were short-lived and mainly literary in focus: ''

The earliest samizdat periodicals were short-lived and mainly literary in focus: ''

In its early years, samizdat defined itself as a primarily literary phenomenon that included the distribution of poetry, classic unpublished Russian literature, and famous 20th century foreign literature. Literature played a key role in the existence of the samizdat phenomenon. For instance, the USSR's refusal to publish Boris Pasternak's epic novel, '' Doctor Zhivago'' led to the novel's subsequent underground publication. Likewise, the circulation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous work about the gulag system, '' The Gulag Archipelago'', promoted a samizdat revival during the mid-1970s. However, because samizdat by definition placed itself in opposition to the state, samizdat works became increasingly focused on the state's violation of human rights, before shifting towards politics.

In its early years, samizdat defined itself as a primarily literary phenomenon that included the distribution of poetry, classic unpublished Russian literature, and famous 20th century foreign literature. Literature played a key role in the existence of the samizdat phenomenon. For instance, the USSR's refusal to publish Boris Pasternak's epic novel, '' Doctor Zhivago'' led to the novel's subsequent underground publication. Likewise, the circulation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous work about the gulag system, '' The Gulag Archipelago'', promoted a samizdat revival during the mid-1970s. However, because samizdat by definition placed itself in opposition to the state, samizdat works became increasingly focused on the state's violation of human rights, before shifting towards politics.

Within samizdat, several works focused on the possibility of a democratic political system. Democratic samizdat possessed a revolutionary nature because of its claim that a fundamental shift in political structure was necessary to reform the state, unlike socialists, who hoped to work within the same basic political framework to achieve change. Despite the revolutionary nature of the democratic samizdat authors, most democrats advocated moderate strategies for change. Most democrats believed in an evolutionary approach to achieving democracy in the USSR, and they focused on advancing their cause along open, public routes, rather than underground routes.

In opposition to both democratic and socialist samizdat, Slavophile samizdat grouped democracy and socialism together as Western ideals that were unsuited to the Eastern European mentality. Slavophile samizdat brought a nationalistic Russian perspective to the political debate, and espoused the importance of cultural diversity and the uniqueness of Slavic cultures. Samizdat written from the Slavophile perspective attempted to unite the USSR under a vision of a shared glorious history of Russian autocracy and Orthodoxy. Consequently, the fact that the USSR encompassed a diverse range of nationalities and lacked a singular Russian history hindered the Slavophile movement. By espousing frequently racist and anti-Semitic views of Russian superiority, through either purity of blood or the strength of Russian Orthodoxy, the Slavophile movement in samizdat alienated readers and created divisions within the opposition.

Within samizdat, several works focused on the possibility of a democratic political system. Democratic samizdat possessed a revolutionary nature because of its claim that a fundamental shift in political structure was necessary to reform the state, unlike socialists, who hoped to work within the same basic political framework to achieve change. Despite the revolutionary nature of the democratic samizdat authors, most democrats advocated moderate strategies for change. Most democrats believed in an evolutionary approach to achieving democracy in the USSR, and they focused on advancing their cause along open, public routes, rather than underground routes.

In opposition to both democratic and socialist samizdat, Slavophile samizdat grouped democracy and socialism together as Western ideals that were unsuited to the Eastern European mentality. Slavophile samizdat brought a nationalistic Russian perspective to the political debate, and espoused the importance of cultural diversity and the uniqueness of Slavic cultures. Samizdat written from the Slavophile perspective attempted to unite the USSR under a vision of a shared glorious history of Russian autocracy and Orthodoxy. Consequently, the fact that the USSR encompassed a diverse range of nationalities and lacked a singular Russian history hindered the Slavophile movement. By espousing frequently racist and anti-Semitic views of Russian superiority, through either purity of blood or the strength of Russian Orthodoxy, the Slavophile movement in samizdat alienated readers and created divisions within the opposition.

Ribs, "music on the ribs", "bone records", or ''roentgenizdat'' (''roentgen-'' from the Russian term for X-ray, named for Wilhelm Röntgen) were homemade phonograph records, copied from forbidden recordings that were smuggled into the country. Their content was Western

Ribs, "music on the ribs", "bone records", or ''roentgenizdat'' (''roentgen-'' from the Russian term for X-ray, named for Wilhelm Röntgen) were homemade phonograph records, copied from forbidden recordings that were smuggled into the country. Their content was Western

December 1970 report by KGB regarding "alarming political tendencies"in Samizdat

an

Preventive measures

(from th

, collected by Vladimir Bukovsky)

Alexander Bolonkin – Memoirs of Soviet Political Prisoner

detailing some technology used

Anthology of samizdat

* * * * *

Вѣхи (Vekhi Library, in Russian)

Anthology of Czech samizdat periodicals

Collection of full texts of Czech exile and samizdat periodicals - scriptum.cz

Archive of Robert-Havemann-Society e.V., Berlin

Arbeitsgruppe Menschenrechte/ Arbeitskreis Gerechtigkeit (Hrsg.): ''Die Mücke. Dokumentation der Ereignisse in Leipzig'', DDR-Samisdat, Leipzig, März 1989.

IFM-Archiv Sachsen e.V.

Internet-Collection of DDR-Samizdat

DDR-Samizdat in Archiv Bürgerbewegung Leipzig

Umweltbibliothek Großhennersdorf e.V.

* DDR-Samisdat in th

IISG Amsterdam

poem by

"Chronicle of current events"

by Memorial Society {{Authority control Censorship in the Eastern Bloc Censorship in the Soviet Union Eastern Bloc mass media Newspapers published in Slovakia Polish dissident organisations Polish literature Political repression in the Soviet Union Second economy of the Soviet Union Soviet culture Soviet phraseology Ukrainian anti-Soviet resistance movement Underground press Self-publishing

dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

activity across the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual reproduction was widespread, because most typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selective ...

s and printing devices required official registration and permission to access. This was a grassroots practice used to evade official Soviet censorship.

Name origin and variations

Etymologically, the word ''samizdat'' derives from ''sam'' (, "self, by oneself") and ''izdat'' (, an abbreviation of , , "publishing house"), and thus means "self-published". The Ukrainian language has a similar term: ''samvydav'' (самвидав), from ''sam'', "self", and ''vydavnytstvo'', "publishing house". A Russian poetNikolay Glazkov

Nikolay Ivanovich Glazkov ( rus, Николай Иванович Глазков, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ ɡlɐˈskof, a=Nikolay Ivanovich Glazkov.ru.vorb.oga; 30 January 19191 October 1979) was a Soviet and Russian poet who coined the t ...

coined a version of the term as a pun in the 1940s when he typed copies of his poems and included the note ''Samsebyaizdat'' (Самсебяиздат, "Myself by Myself Publishers") on the front page.

''Tamizdat'' refers to literature published abroad (там, ''tam'', "there"), often from smuggled manuscripts.

The Polish term for this phenomenon coined around 1980 was 'drugi obieg', or the 'second circuit' of publishing.

Techniques

All Soviet-producedtypewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selective ...

s and printing devices were officially registered, with their typographic samples collected right at the factory and stored in the government directory. Because every typewriter has micro features which are individual as much as human fingerprints, it allowed the KGB investigators to promptly identify the device which was used to type or print the text in question, and apprehend its user. However, certain East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

and Eastern European

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

-made Cyrillic typewriters, most notably the Erika, were purchased by Soviet citizens while traveling to nearby socialist countries, skipped the sample collection procedure and therefore presented more difficulty to trace. Western-produced typewriters, purchased abroad and somehow brought or smuggled into the Soviet Union, were used to type Cyrillic text via Latin characters. To prevent capture, regular bookbinding of ideologically-approved books have been used to conceal the forbidden texts within.

Samizdat copies of texts, such as Mikhail Bulgakov's novel '' The Master and Margarita'' or Václav Havel

Václav Havel (; 5 October 193618 December 2011) was a Czech statesman, author, poet, playwright, and former dissident. Havel served as the last president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1992 and the ...

's essay '' The Power of the Powerless'' were passed around among trusted friends. The techniques used to reproduce these forbidden texts varied. Several copies might be made using carbon paper

Carbon paper (originally carbonic paper) consists of sheets of paper which create one or more copies simultaneously with the creation of an original document when inscribed by a typewriter or ballpoint pen.

History

In 1801, Pellegrino Tur ...

, either by hand or on a typewriter; at the other end of the scale, mainframe computer printers were used during night shifts to make multiple copies, and books were at times printed on semiprofessional printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

es in much larger quantities. Before glasnost, most of these methods were dangerous, because copy machines, printing presses, and even typewriters in offices were under control of the organization's First Department

The First Department (russian: Первый отдел) was in charge of secrecy and political security of the workplace of every enterprise or institution of the Soviet Union that dealt with any kind of technical or scientific information (p ...

(part of the KGB); reference printouts from all of these machines were stored for subsequent identification purposes, should samizdat output be found.

Physical form

Samizdat distinguishes itself not only by the ideas and debates that it helped spread to a wider audience but also by its physical form. The hand-typed, often blurry and wrinkled pages with numerous typographical errors and nondescript covers helped to separate and elevate Russian samizdat from Western literature. The physical form of samizdat arose from a simple lack of resources and the necessity to be inconspicuous. In time, dissidents in the USSR began to admire these qualities for their own sake, the ragged appearance of samizdat contrasting sharply with the smooth, well-produced appearance of texts passed by the censor's office for publication by the State. The form samizdat took gained precedence over the ideas it expressed, and became a potent symbol of the resourcefulness and rebellious spirit of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union. In effect, the physical form of samizdat itself elevated the reading of samizdat to a prized clandestine act.

Samizdat distinguishes itself not only by the ideas and debates that it helped spread to a wider audience but also by its physical form. The hand-typed, often blurry and wrinkled pages with numerous typographical errors and nondescript covers helped to separate and elevate Russian samizdat from Western literature. The physical form of samizdat arose from a simple lack of resources and the necessity to be inconspicuous. In time, dissidents in the USSR began to admire these qualities for their own sake, the ragged appearance of samizdat contrasting sharply with the smooth, well-produced appearance of texts passed by the censor's office for publication by the State. The form samizdat took gained precedence over the ideas it expressed, and became a potent symbol of the resourcefulness and rebellious spirit of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union. In effect, the physical form of samizdat itself elevated the reading of samizdat to a prized clandestine act.

Readership

Samizdat originated from the dissident movement of the Russian

Samizdat originated from the dissident movement of the Russian intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, and most samizdat directed itself to a readership of Russian elites. While circulation of samizdat was relatively low, at around 200,000 readers on average, many of these readers possessed positions of cultural power and authority. Furthermore, because of the presence of " dual consciousness" in the Soviet Union, the simultaneous censorship of information and necessity of absorbing information to know how to censor it, many government officials became readers of samizdat. Although the general public at times came into contact with samizdat, most of the public lacked access to the few expensive samizdat texts in circulation, and expressed discontent with the highly censored reading material made available by the state.

The purpose and methods of samizdat may contrast with the purpose of the concept of copyright.

History

Self-published and self-distributed literature has a long history in Russia. ''Samizdat'' is unique to the post-Stalin USSR and other countries with similar systems. Faced with the state's powers of censorship, society turned to underground literature for self-analysis and self-expression.Samizdat books and editions

The first full-length book to be distributed as samizdat was Boris Pasternak's 1957 novel '' Doctor Zhivago''. Although the literary magazine ''Novy Mir

''Novy Mir'' (russian: links=no, Новый мир, , ''New World'') is a Russian-language monthly literary magazine.

History

''Novy Mir'' has been published in Moscow since January 1925. It was supposed to be modelled on the popular pre- Soviet ...

'' had published ten poems from the book in 1954, a year later the full text was judged unsuitable for publication and entered samizdat circulation.

Certain works, though published legally by the State-controlled media, were practically impossible to find in bookshops and libraries, and found their way into samizdat: for example Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's novel '' One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich'' was widely distributed via samizdat.

At the outset of the Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw ( rus, хрущёвская о́ттепель, r=khrushchovskaya ottepel, p=xrʊˈɕːɵfskəjə ˈotʲ:ɪpʲɪlʲ or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period ...

in the mid-1950s USSR poetry became very popular. Writings of a wide variety of poets circulated among Soviet intelligentsia: known, prohibited, repressed writers as well as those young and unknown. A number of samizdat publications carried unofficial poetry, among them the Moscow magazine ''Sintaksis

''Sintaksis: publitsistika, kritika, polemika'' (russian: Синтаксис: публицистика, критика, полемика), was a journal published in Paris in 1978–2001 with Maria Rozanova as chief editor. A total of 37 issues o ...

'' (1959–1960) by writer Alexander Ginzburg, Vladimir Osipov's ''Boomerang'' (1960), and '' Phoenix'' (1961), produced by Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg. The editors of these magazines were regulars at impromptu public poetry readings between 1958 and 1961 on Mayakovsky Square in Moscow. The gatherings did not last long, for soon the authorities began clamping down on them. In the summer of 1961, several meeting regulars were arrested and charged with " anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda" (Article 70 of the RSFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

Penal Code), putting an end to most of the magazines.

Not everything published in samizdat had political overtones. In 1963, Joseph Brodsky was charged with " social parasitism" and convicted for being nothing but a poet. His poems circulated in samizdat, with only four judged as suitable for official Soviet anthologies. In the mid-1960s an unofficial literary group known as SMOG

Smog, or smoke fog, is a type of intense air pollution. The word "smog" was coined in the early 20th century, and is a portmanteau of the words '' smoke'' and ''fog'' to refer to smoky fog due to its opacity, and odor. The word was then in ...

(a word meaning variously ''one was able'', ''I did it'', etc.; as an acronym the name also bore a range of interpretations) issued an almanac

An almanac (also spelled ''almanack'' and ''almanach'') is an annual publication listing a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, tide tables, and othe ...

titled ''The Sphinxes'' (''Sfinksy'') and collections of prose and poetry. Some of their writings were close to the Russian avant-garde

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its ...

of the 1910s and 1920s.

The 1965 show trial of writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky, charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, and the subsequent increased repression, marked the demise of the Thaw and the beginning of harsher times for samizdat authors. The trial was carefully documented in a samizdat collection called ''The White Book'' (1966), compiled by Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg. Both writers were among those later arrested and sentenced to prison in what was known as Trial of the Four. In the following years some samizdat content became more politicized, and played an important role in the dissident movement in the Soviet Union.

Samizdat periodicals

The earliest samizdat periodicals were short-lived and mainly literary in focus: ''

The earliest samizdat periodicals were short-lived and mainly literary in focus: ''Sintaksis

''Sintaksis: publitsistika, kritika, polemika'' (russian: Синтаксис: публицистика, критика, полемика), was a journal published in Paris in 1978–2001 with Maria Rozanova as chief editor. A total of 37 issues o ...

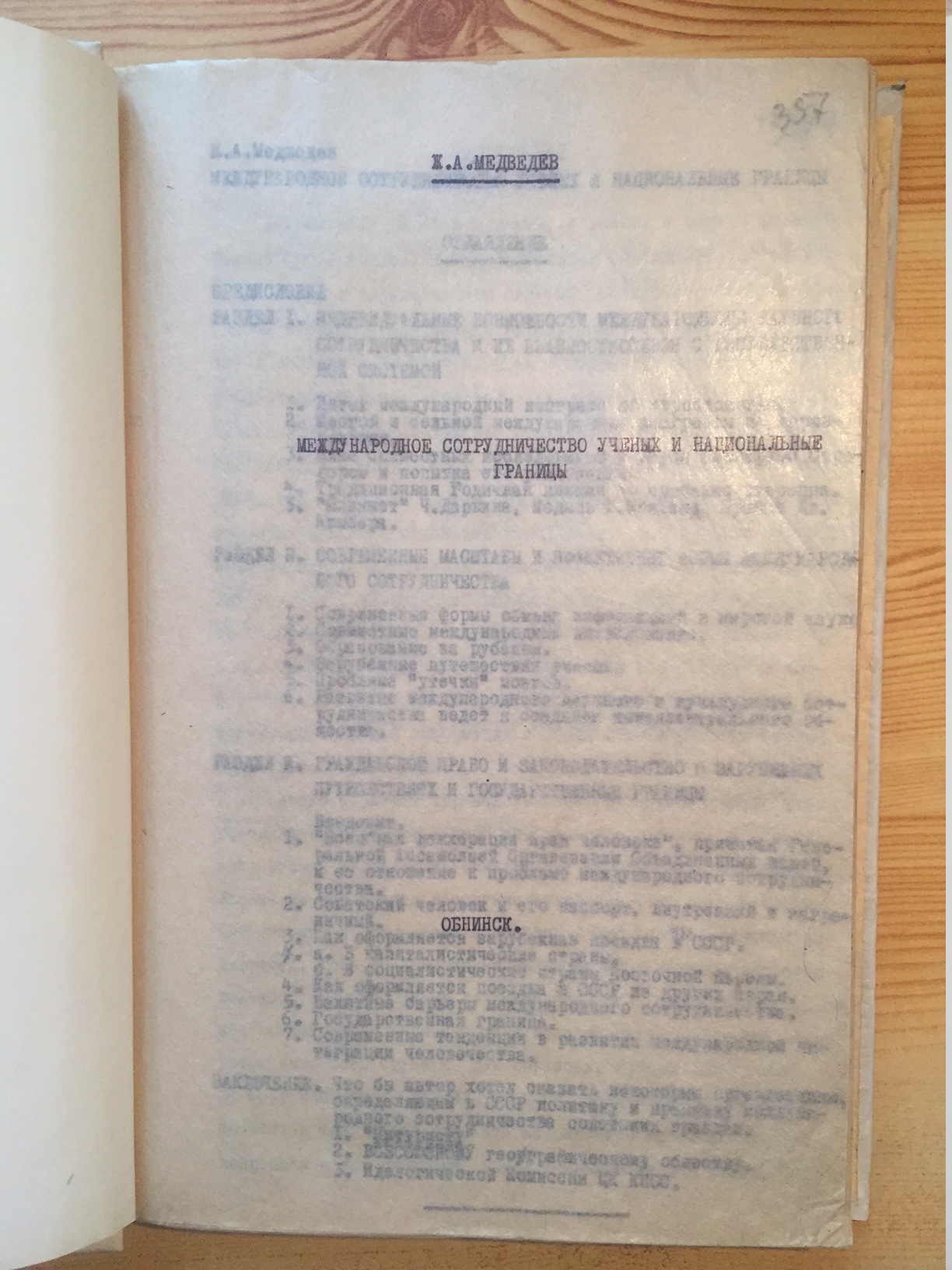

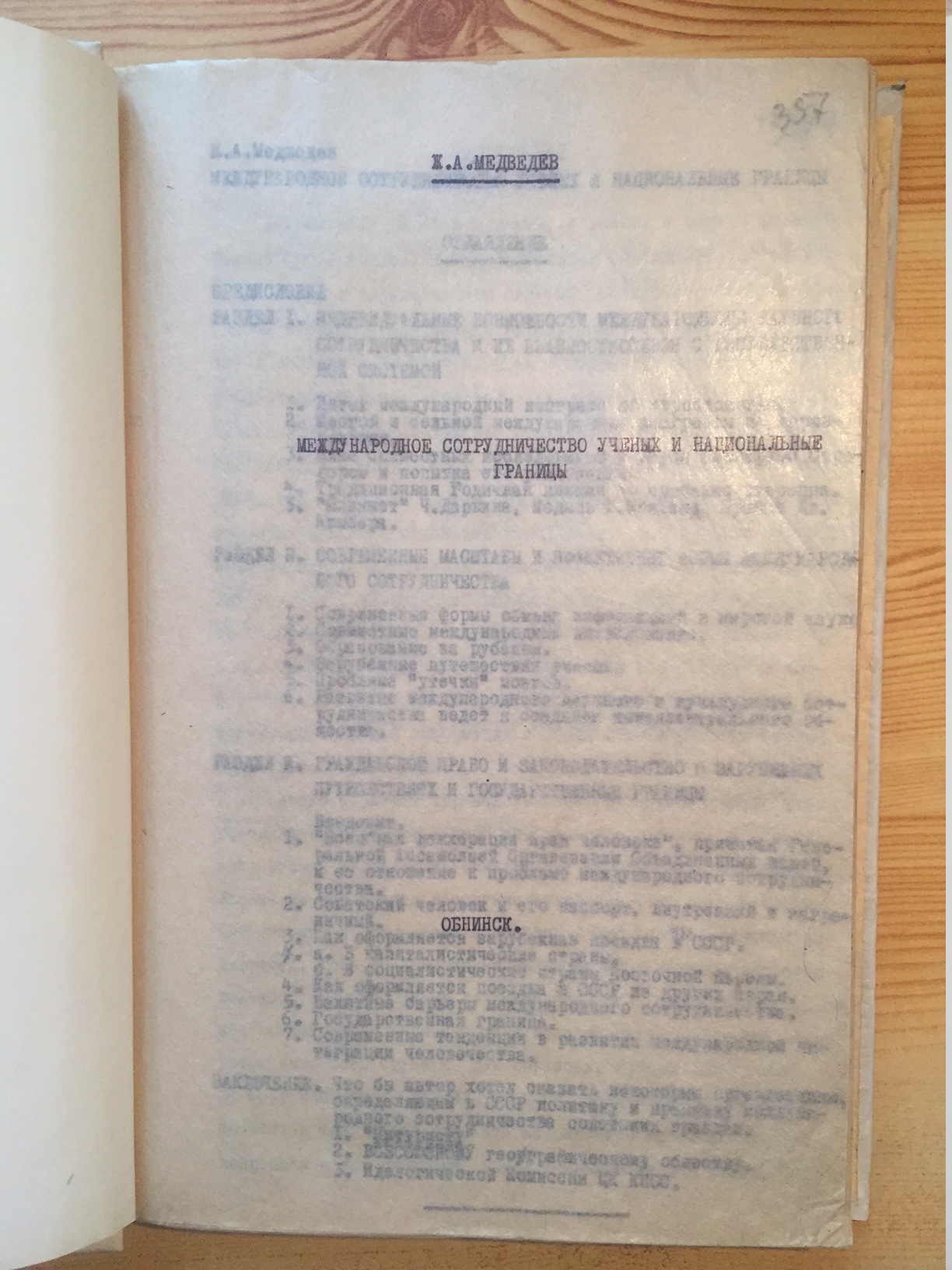

'' (1959–1960), ''Boomerang'' (1960), and '' Phoenix'' (1961). From 1964 to 1970, communist historian Roy Medvedev regularly published ''The Political Journal'' (Политический дневник, or political diary), which contained analytical materials that later appeared in the West.

The longest-running and best-known samizdat periodical was ''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (Хроника текущих событий). It was dedicated to defending human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

by providing accurate information about events in the USSR. Over 15 years, from April 1968 to December 1982, 65 issues were published, all but two appearing in English translation. The anonymous editors encouraged the readers to utilize the same distribution channels in order to send feedback and local information to be published in subsequent issues.

The ''Chronicle'' was distinguished by its dry, concise style and punctilious correction of even the smallest error. Its regular rubrics were "Arrests, Searches, Interrogations", "Extra-judicial Persecution", "In Prisons and Camps", "Samizdat update", "News in brief", and "Persecution of Religion". Over time, sections were added on the "Persecution of the Crimean Tatars", "Persecution and Harassment in Ukraine", "Lithuanian Events", and so on.

The ''Chronicle'' editors maintained that, according to the 1936 Soviet Constitution, then in force, their publication was not illegal. The authorities did not accept the argument. Many people were harassed, arrested, imprisoned, or forced to leave the country for their involvement in the ''Chronicle''s production and distribution. The periodical's typist and first editor Natalya Gorbanevskaya was arrested and put in a psychiatric hospital for taking part in the August 1968 Red Square protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1974, two of the periodical's close associates (Pyotr Yakir and Victor Krasin) were persuaded to denounce their fellow editors and the ''Chronicle'' on Soviet television. This put an end to the periodical's activities, until Sergei Kovalev, Tatyana Khodorovich and Tatyana Velikanova openly announced their readiness to resume publication. After being arrested and imprisoned, they were replaced, in turn, by others.

Another notable and long-running (about 20 issues in the period of 1972–1980) publication was the '' refusenik'' political and literary magazine "Евреи в СССР" (Yevrei v SSSR, ''Jews in the USSR''), founded and edited by Alexander Voronel and, after his imprisonment, by Mark Azbel

Mark Yakovlevich Azbel (russian: Марк Яковлевич Азбель; 12 May 1932 — 31 March 2020) was a Soviet and Israeli physicist. He was a member of the American Physical Society.

Between 1956 and 1958, he experimentally demonstrate ...

and Alexander Luntz.

The late 1980s, which were marked by an increase in informal organizations, saw a renewed wave of samizdat periodicals in the Soviet Union. Publications that were active during that time included ''Glasnost'' (edited by Sergei Grigoryants), ''Ekspress-khronika'' (''Express-Chronicle,'' edited by Alexander Podrabinek), ''Svobodnoye slovo'' ("Free word", by the Democratic Union formed in May 1988), ''Levyi povorot'' ("Left turn", edited by Boris Kagarlitsky), ''Otkrytaya zona'' ("Open zone") of Club Perestroika, ''Merkurii'' ("Mercury", edited by Elena Zelinskaya) and ''Khronograph'' ("Chronograph", put out by a number of Moscow activists).

Not all samizdat trends were liberal or clearly opposed to the Soviet regime and the literary establishment. "The ''Russian Party''... was a very strange element of the political landscape of Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

's era—feeling themselves practically dissidents, members of the ''Russian Party'' with rare exceptions took quite prestigious official positions in the world of writers or journalists," wrote Oleg Kashin in 2009.

Genres

Samizdat covered a large range of topics, mainly including literature and works focused on religion, nationality, and politics. The state censored a variety of materials such as detective novels, adventure stories, and science fiction in addition to dissident texts, resulting in the underground publication of samizdat covering a wide range of topics. Though most samizdat authors directed their works towards the intelligentsia, samizdat included lowbrow genres in addition to scholarly works. Hyung-Min Joo carried out a detailed analysis of an archive of samizdat (Архив Самиздата, ''Arkhiv Samizdata'') by ''Radio Liberty

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transm ...

'', sponsored by the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

and launched in the 1960s, and reported that of its 6,607 items, 1% were literary, 17% nationalist, 20% religious, and 62% political, noting that as a rule, literary works were not collected there, so their 1% (only 73 texts) are not representative of their real share of circulation.

Literary

In its early years, samizdat defined itself as a primarily literary phenomenon that included the distribution of poetry, classic unpublished Russian literature, and famous 20th century foreign literature. Literature played a key role in the existence of the samizdat phenomenon. For instance, the USSR's refusal to publish Boris Pasternak's epic novel, '' Doctor Zhivago'' led to the novel's subsequent underground publication. Likewise, the circulation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous work about the gulag system, '' The Gulag Archipelago'', promoted a samizdat revival during the mid-1970s. However, because samizdat by definition placed itself in opposition to the state, samizdat works became increasingly focused on the state's violation of human rights, before shifting towards politics.

In its early years, samizdat defined itself as a primarily literary phenomenon that included the distribution of poetry, classic unpublished Russian literature, and famous 20th century foreign literature. Literature played a key role in the existence of the samizdat phenomenon. For instance, the USSR's refusal to publish Boris Pasternak's epic novel, '' Doctor Zhivago'' led to the novel's subsequent underground publication. Likewise, the circulation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous work about the gulag system, '' The Gulag Archipelago'', promoted a samizdat revival during the mid-1970s. However, because samizdat by definition placed itself in opposition to the state, samizdat works became increasingly focused on the state's violation of human rights, before shifting towards politics.

Political

The majority of samizdat texts were politically focused. Most of the political texts were personal statements, appeals, protests, or information on arrests and trials. Other political samizdat included analyses of various crises within the USSR, and suggested alternatives to the government's handling of events. No unified political thought existed within samizdat; rather, authors debated from a variety of perspectives. Samizdat written from socialist, democratic and Slavophile perspectives dominated the debates. Socialist authors compared the current state of the government to the Marxist ideals of socialism, and appealed to the state to fulfil its promises. Socialist samizdat writers hoped to give a "human face" to socialism by expressing dissatisfaction with the system of censorship. Many socialists put faith in the potential for reform in the Soviet Union, especially because of the political liberalization which occurred under Dubček in Czechoslovakia. However, the Soviet Union invasion of a liberalizing Czechoslovakia, in the events of " Prague Spring", crushed hopes for reform and stymied the power of the socialist viewpoint. Because the state proved itself unwilling to reform, samizdat began to focus on alternative political systems. Within samizdat, several works focused on the possibility of a democratic political system. Democratic samizdat possessed a revolutionary nature because of its claim that a fundamental shift in political structure was necessary to reform the state, unlike socialists, who hoped to work within the same basic political framework to achieve change. Despite the revolutionary nature of the democratic samizdat authors, most democrats advocated moderate strategies for change. Most democrats believed in an evolutionary approach to achieving democracy in the USSR, and they focused on advancing their cause along open, public routes, rather than underground routes.

In opposition to both democratic and socialist samizdat, Slavophile samizdat grouped democracy and socialism together as Western ideals that were unsuited to the Eastern European mentality. Slavophile samizdat brought a nationalistic Russian perspective to the political debate, and espoused the importance of cultural diversity and the uniqueness of Slavic cultures. Samizdat written from the Slavophile perspective attempted to unite the USSR under a vision of a shared glorious history of Russian autocracy and Orthodoxy. Consequently, the fact that the USSR encompassed a diverse range of nationalities and lacked a singular Russian history hindered the Slavophile movement. By espousing frequently racist and anti-Semitic views of Russian superiority, through either purity of blood or the strength of Russian Orthodoxy, the Slavophile movement in samizdat alienated readers and created divisions within the opposition.

Within samizdat, several works focused on the possibility of a democratic political system. Democratic samizdat possessed a revolutionary nature because of its claim that a fundamental shift in political structure was necessary to reform the state, unlike socialists, who hoped to work within the same basic political framework to achieve change. Despite the revolutionary nature of the democratic samizdat authors, most democrats advocated moderate strategies for change. Most democrats believed in an evolutionary approach to achieving democracy in the USSR, and they focused on advancing their cause along open, public routes, rather than underground routes.

In opposition to both democratic and socialist samizdat, Slavophile samizdat grouped democracy and socialism together as Western ideals that were unsuited to the Eastern European mentality. Slavophile samizdat brought a nationalistic Russian perspective to the political debate, and espoused the importance of cultural diversity and the uniqueness of Slavic cultures. Samizdat written from the Slavophile perspective attempted to unite the USSR under a vision of a shared glorious history of Russian autocracy and Orthodoxy. Consequently, the fact that the USSR encompassed a diverse range of nationalities and lacked a singular Russian history hindered the Slavophile movement. By espousing frequently racist and anti-Semitic views of Russian superiority, through either purity of blood or the strength of Russian Orthodoxy, the Slavophile movement in samizdat alienated readers and created divisions within the opposition.

Religious

Predominantly Orthodox, Catholic, Baptist, Pentecostalist, and Adventist groups authored religious samizdat texts. Though a diversity of religious samizdat circulated, including three Buddhist texts, no known Islamic samizdat texts exist. The lack of Islamic samizdat appears incongruous with the large percentage of Muslims who resided in the USSR.Nationalist

Jewish samizdat importantly advocated for the end of repression of Jews in the USSR and expressed a desire forexodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Exo ...

, the ability to leave Russia for an Israeli homeland. Jewish samizdat encouraged Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

. The exodus movement also broached broader topics of human rights and freedoms of Soviet citizens. However, a divide existed within Jewish samizdat between authors who advocated exodus, and those who argued that Jews should remain in the USSR to fight for their rights.

Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

and Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (german: Wolgadeutsche, ), russian: поволжские немцы, povolzhskiye nemtsy) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov ...

also created samizdat, protesting the state's refusal to allow them to return to their homelands following Stalin's death.

Ukrainian samizdat opposed the assumed superiority of Russian culture over the Ukrainian and condemned the forced assimilation of Ukrainians to the Russian language.

In addition to samizdat focused on Jewish, Ukrainian, and Crimean Tartar concerns, authors also advocated the causes of a great many other nationalities.

Contraband audio

Ribs, "music on the ribs", "bone records", or ''roentgenizdat'' (''roentgen-'' from the Russian term for X-ray, named for Wilhelm Röntgen) were homemade phonograph records, copied from forbidden recordings that were smuggled into the country. Their content was Western

Ribs, "music on the ribs", "bone records", or ''roentgenizdat'' (''roentgen-'' from the Russian term for X-ray, named for Wilhelm Röntgen) were homemade phonograph records, copied from forbidden recordings that were smuggled into the country. Their content was Western rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm an ...

, jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a majo ...

, mambo, and other music, and music by banned emigres. They were sold and traded on the black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the ...

.

Each disc is a thin, flexible plastic sheet recorded with a spiral groove on one side, playable on a normal phonograph turntable at 78 RPM. They were made from an inexpensive, available material: used X-ray film (hence the name ''roentgenizdat''). Each large rectangular sheet was trimmed into a circle and individually recorded using an improvised recording lathe. The discs and their limited sound quality resemble the mass-produced flexi disc, and may have been inspired by it.

'' Magnitizdat'' (''magnit-'' from ''magnitofon'', the Russian word for tape recorder

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present ...

) is the distribution of sound recordings on audio tape, often of bards, Western artists, and underground music groups. ''Magnitizdat'' replaced ''roentgenizdat'', as it was cheaper and more efficient method of reproduction that resulted in higher quality copies.

Further influence

AfterBell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

changed its UNIX

Unix (; trademarked as UNIX) is a family of multitasking, multiuser computer operating systems that derive from the original AT&T Unix, whose development started in 1969 at the Bell Labs research center by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, a ...

licence in 1979 to make dissemination of the source code illegal, the 1976 Lions book which contained the source code had to be withdrawn, but illegal copies of it circulated for years.

The act of copying the Lions book was often referred to as samizdat. In hacker and computer jargon, the term samizdat was used for the dissemination of needed and hard to obtain documents or information.

The hacker journal '' PoCGTFO'' calls its distribution permissions a ''samizdat'' licence.

Notable samizdat periodicals

* '' A-YA'' *Bulletin "V"

Bulletin "V" (russian: Бюллетень В) was a Samizdat human rights publication produced in Russian and circulated in the Soviet Union in 1980–1983. Samizdat was a form of dissident activity across the socialist Eastern Bloc in which indi ...

* '' Chronicle of Current Events''

* '' Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania''

* '' Phoenix''

* ''Sintaksis

''Sintaksis: publitsistika, kritika, polemika'' (russian: Синтаксис: публицистика, критика, полемика), was a journal published in Paris in 1978–2001 with Maria Rozanova as chief editor. A total of 37 issues o ...

''

See also

* Anna's Archive * Eastern Bloc media and propaganda * Gosizdat * Human rights in the Soviet Union * Library Genesis, free articles and books, 21st century Russia *Political repression in the Soviet Union

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, tens of millions of people suffered political repression, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution. It culminated during the Stalin era, then declined, but it continued to exist ...

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1987)

A new and more aggressive phase of anti-religious persecution in the Soviet Union began in the mid-1970s after a more tolerant period following Nikita Khrushchev's downfall in 1964.

Yuri Andropov headed the campaign in the 1970s when it began to r ...

Citations

General sources

* * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

Outsiders' works

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Insiders' works

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

December 1970 report by KGB regarding "alarming political tendencies"in Samizdat

an

Preventive measures

(from th

, collected by Vladimir Bukovsky)

Alexander Bolonkin – Memoirs of Soviet Political Prisoner

detailing some technology used

Anthology of samizdat

* * * * *

Вѣхи (Vekhi Library, in Russian)

Anthology of Czech samizdat periodicals

Collection of full texts of Czech exile and samizdat periodicals - scriptum.cz

Archive of Robert-Havemann-Society e.V., Berlin

Arbeitsgruppe Menschenrechte/ Arbeitskreis Gerechtigkeit (Hrsg.): ''Die Mücke. Dokumentation der Ereignisse in Leipzig'', DDR-Samisdat, Leipzig, März 1989.

IFM-Archiv Sachsen e.V.

Internet-Collection of DDR-Samizdat

DDR-Samizdat in Archiv Bürgerbewegung Leipzig

Umweltbibliothek Großhennersdorf e.V.

* DDR-Samisdat in th

IISG Amsterdam

poem by

Jared Carter Jared Carter may refer to:

*Jared Carter (Latter Day Saints) (1801-1849), an early missionary in the Latter Day Saint movement

*Jared Carter (poet)

Jared Carter (born January 10, 1939) is an American poet and editor.

Life

Carter was born in a sm ...

"Chronicle of current events"

by Memorial Society {{Authority control Censorship in the Eastern Bloc Censorship in the Soviet Union Eastern Bloc mass media Newspapers published in Slovakia Polish dissident organisations Polish literature Political repression in the Soviet Union Second economy of the Soviet Union Soviet culture Soviet phraseology Ukrainian anti-Soviet resistance movement Underground press Self-publishing