Sally Mapp on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sarah "Crazy Sally" Mapp (baptised 1706 – 1737) was an English lay

A song about Mapp appeared in a contemporary play at

A song about Mapp appeared in a contemporary play at

bonesetter

Traditional bone-setting is a type of a folk medicine in which practitioners engaged in joint manipulation. Before the advent of chiropractors, osteopaths and physical therapists, bone-setters were the main providers of this type of treatment. ...

, who gained fame both by performing impressive bone-setting acts in Epsom and London, and by being a woman in a male-dominated profession. Bone-setting was a medical practice used to manipulate and fix musculoskeletal injuries using manual force. Mapp grew up in Wiltshire, England, and learned about the practice from her father, who was also a bone-setter. She frequently fixed horse racing injuries, but her most famous case was fixing the spinal deformity of Sir Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector, with a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Mu ...

's niece.

Early life

Sarah Mapp was baptized in 1706 near Wiltshire, England. She was the daughter of John and Jenny Wallin. John Wallin was a bone-setter as well, and when he was unable to conduct bone setting practices, Mapp carried on and dealt with the cases, often even better than her father. She accordingly left him and established her own practice called 'Cracked Sally - the One and Only Bone Setter'. Mapp's nickname 'Crazy Sally' came from her masculine personality and reputation for quarreling with her father and drinking. Mapp could often be found wandering the country in a drunken state and shouting obscenities, which also contributed to her nickname. Mapp's sister Lavinia Fenton had a considerably different life. Lavinia Fenton played Polly Peachum in ''The Beggar's Opera

''The Beggar's Opera'' is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of satiri ...

'' in 1728 and later married Charles Powlett, 3rd Duke of Bolton.

Practice

Bone-setting in the 18th century was often carried out by men, specificallyfarrier

A farrier is a specialist in equine hoof care, including the trimming and balancing of horses' hooves and the placing of shoes on their hooves, if necessary. A farrier combines some blacksmith's skills (fabricating, adapting, and adj ...

s and blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

s, because it required a lot of strength. Mapp's career started out when she was a young girl. She served as the announcer at her father's booth during local races and fairs. When Mapp started helping her father's patients when he couldn't see them, she often performed amazing feats and treated them better than her father could. Mapp went on to start her own practice and her fame spread. Around 1735, Mapp's fame for fixing decade-old dislocations and fractures brought her to Epsom

Epsom is the principal town of the Borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, England, about south of central London. The town is first recorded as ''Ebesham'' in the 10th century and its name probably derives from that of a Saxon landowner. The ...

. Epsom was home to a large number of wealthy families and horse-racing, which provided Mapp with many patients. Even though Mapp had a limited knowledge of anatomy, she had the strength and innate talent for putting dislocations back into place.

The racing community in Epsom appreciated Mapp's work and when they found out she might leave, the town offered Mapp 100 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

yearly to reside there and set bones in 1736. While living in Epsom, she traveled to London twice a week and saw patients at the Grecian Coffee House

The Grecian Coffee House was a coffee house, first established in about 1665 at Wapping Old Stairs in London, England, by a Greek former mariner called George Constantine.

The enterprise proved a success and, by 1677, Constantine had been able t ...

. Mapp traveled to London in style with an expensive coach and a team of four horses. She would collect the crutches of her cured patients and decorate her carriage with them. At the same time, Sir Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector, with a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Mu ...

was also prescribing and conducting his private practice out of the Grecian Coffee House. Mapp is credited with fixing a spinal deformity on Sloane's niece, which bolstered her fame in London.

Mapp consulted on and fixed multiple cases. Some of her most noteworthy cases are recorded in James Caulfied's ''Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons'' where he recorded an account from October 21, 1736, "On Monday, Mrs. Mapp performed two extraordinary cures; one on a young lady of the Temple, who had several bones out from the knees to her toes, which she put in their proper places: and the other on a butcher, whose knee-pans were so misplaced that he walked with his knees knocking one against another. Yesterday she performed several other surprising cures; and about one set out for Epsom, and carried with her several crutches, which she calls trophies of honour." At one point, some surgeons tried to fool Mapp and show that she was not skilled by sending her a healthy patient who claimed he had a damaged wrist. This test angered Mapp and she dislocated the patient's wrist and sent him back to the people who had tried to trick her.

Later life

Mapp was once mistaken for one ofGeorge II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

's mistresses while riding in her carriage by an angry mob. She is reported to have responded to the angry mob by yelling, "Damn your blood, don't you know me? I am Mrs. Mapp, the bone-setter." In August 1736, she married an abusive footman

A footman is a male domestic worker employed mainly to wait at table or attend a coach or carriage.

Etymology

Originally in the 14th century a footman denoted a soldier or any pedestrian, later it indicated a foot servant. A running footman deli ...

named Hill Mapp who absconded with 100 guineas of her savings. After initial confusion and anger, Mapp claimed that the money was worth losing to get rid of her husband. In 1737, Mapp died in Seven Dials and was buried by the parish there.

In art

A song about Mapp appeared in a contemporary play at

A song about Mapp appeared in a contemporary play at Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

, '' The Husband's Relief'', comparing her favorably to highly-paid London surgeons. Mapp is reported to have attended the play.

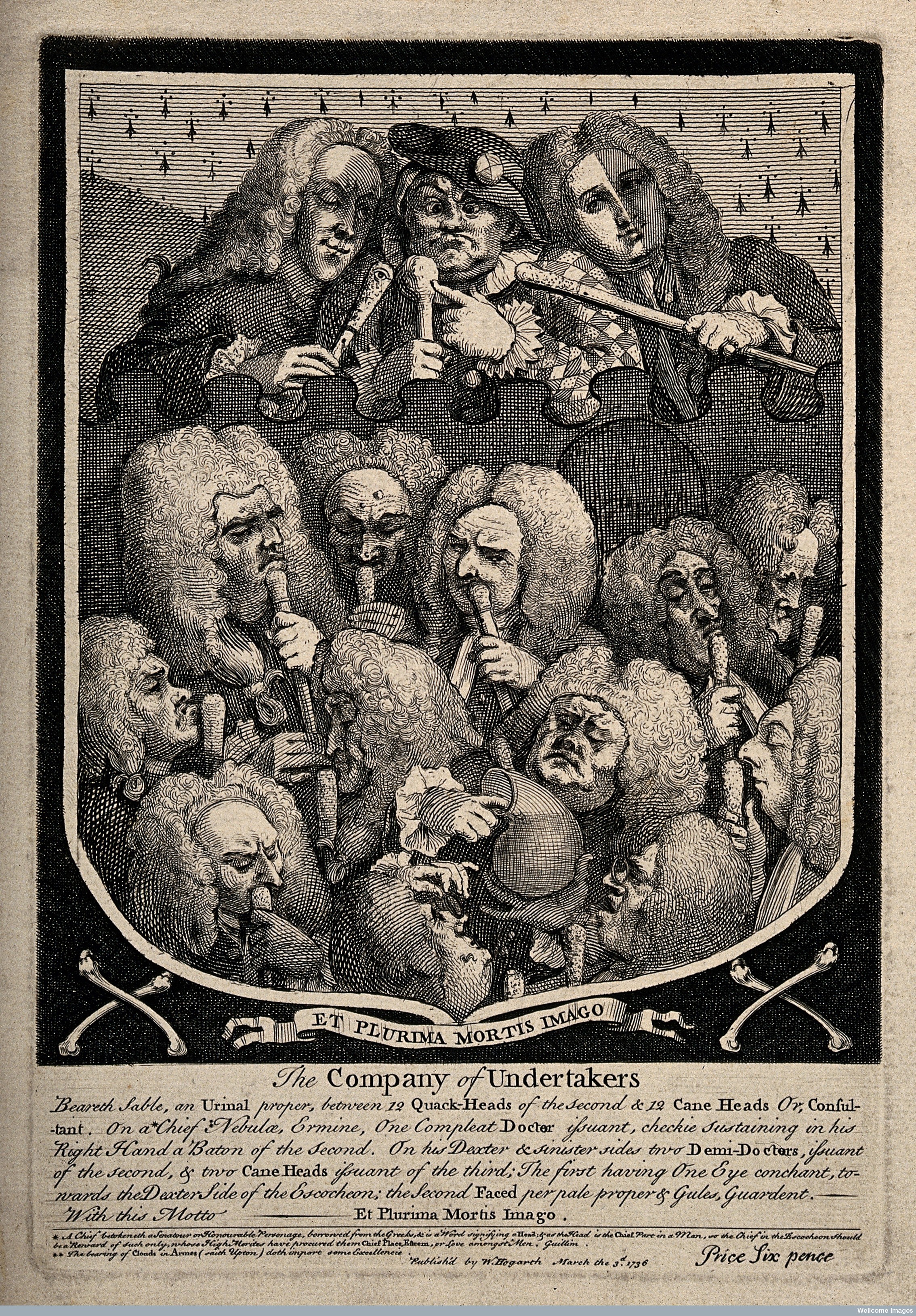

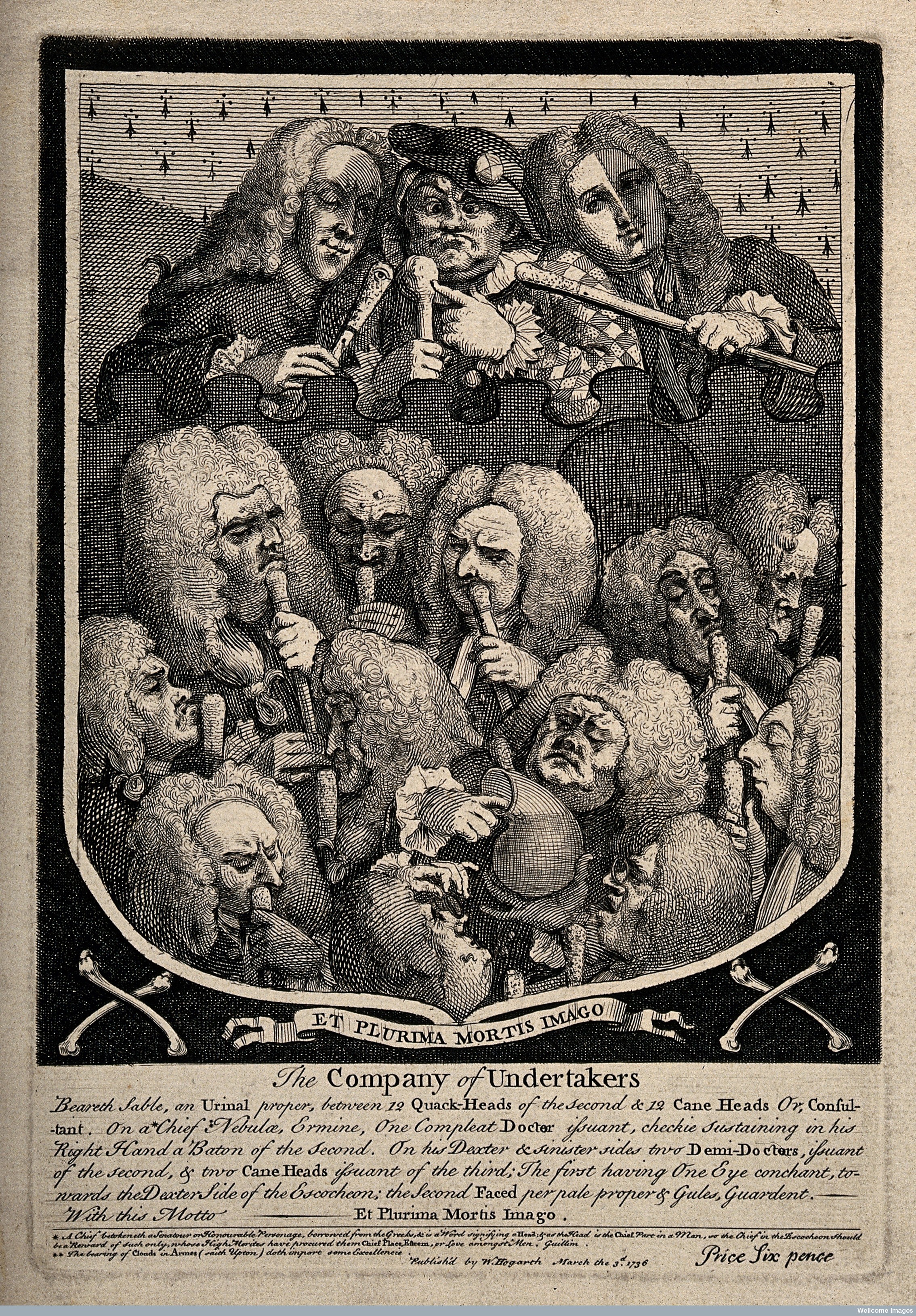

Her portrait appears at the top of William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like ...

's The Company of Undertakers (Consultation of Quacks) (1736), which grouped her with "quacks", but suggested that both the quacks and "professional" physicians of the day might lead to death. In 1819, George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank (27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reache ...

portrayed Mapp, probably based on Hogarth's drawing.

Legacy

Originally, Mapp was well-loved wherever she worked because of her talents as a bone-setter. In Epsom, the racing community especially appreciated her contributions and named a mare Mrs. Mapp in honor of her. However, towards the end of her life, she started to fall out of fame and favor. In 1736, the established medical community started to try to eliminate the "quacks" operating in London, so Mapp moved to Pall Mall. The famous artistWilliam Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like ...

depicted her in his print ''The Company of Undertakers''. Hogarth's print only pushed her further away from fame as he chose to draw her as very masculine and ugly. Hogarth's print was coupled with Sir Percivall Pott

Percivall Pott (6 January 1714, in London – 22 December 1788) was an English surgeon, one of the founders of orthopaedics, and the first scientist to demonstrate that a cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen.

Career

He was the ...

's criticism of Mapp when he called her "an immoral drunken female savage". Both of these attacks on Mapp along with changing social attitudes led to her decline in popularity. This fall from fame caused Mapp to drink heavily and lose her customers. In 1737, Mapp died in Seven Dials and, due to her poverty, was buried by the parish. Sarah Mapp was only alive for thirty years, but she is still well recorded in history because of her character and the fact that she was a very successful female in what was typically considered a male field.

In modern literature, Mapp is widely cited as an example of a quack

Quack, The Quack or Quacks may refer to:

People

* Quack Davis, American baseball player

* Hendrick Peter Godfried Quack (1834–1917), Dutch economist and historian

* Joachim Friedrich Quack (born 1966), German Egyptologist

* Johannes Quack (b ...

. She has been described as an early exponent of osteopathy

Osteopathy () is a type of alternative medicine that emphasizes physical manipulation of the body's muscle tissue and bones. Practitioners of osteopathy are referred to as osteopaths.

Osteopathic manipulation is the core set of techniques in ...

. Samuel Homola has noted that "In the days of Sally Mapp, the treatment appeared to be quite successful in a great many conditions because of the unrecognized effects of suggestive therapy."Homola, Samuel. (1963). ''Bonesetting, Chiropractic and Cultism''. Critique Books. p. 20

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mapp, Sarah 1737 deaths Year of birth unknown 18th-century English people People from Wiltshire