Saint-Louis-du-Louvre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Saint-Louis-du-Louvre, formerly Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, was a medieval church in the

On 8 October 1164,

On 8 October 1164,

By 1739 the church had fallen into ruin and

By 1739 the church had fallen into ruin and

In 1791, at the behest of

In 1791, at the behest of

An article on the church's tombs

{{Authority control Roman Catholic churches in the 1st arrondissement of Paris Reformed churches in Paris Former collegiate churches Destroyed churches in France Former buildings and structures in Paris Buildings and structures demolished in 1811

1st arrondissement of Paris

The 1st arrondissement of Paris (''Ier arrondissement'') is one of the 20 arrondissements of the capital city of France. In spoken French, this arrondissement is colloquially referred to as ''le premier'' (the first). It is governed locally toge ...

located just west of the original Louvre Palace

The Louvre Palace (french: link=no, Palais du Louvre, ), often referred to simply as the Louvre, is an iconic French palace located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in Paris, occupying a vast expanse of land between the Tuileries Ga ...

. It was founded as Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre in 1187 by Robert of Dreux as a Collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a ...

. It had fallen into ruin by 1739 and was rebuilt as Saint-Louis-du-Louvre in 1744. The church was suppressed in 1790 during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

and turned over the next year for use as the first building dedicated to Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

worship in the history of Paris, a role in which it continued until its demolition in 1811 to make way for Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's expansion of the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

. The Reformed

Reform is beneficial change

Reform may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

*''Reforme'' ("Reforms"), initial name of the ...

congregation was given l'Oratoire du Louvre

The Temple protestant de l'Oratoire du Louvre, also Église réformée de l'Oratoire du Louvre, is a historic Protestant church located at 145 rue Saint-Honoré – 160 rue de Rivoli in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, across the street from the Lo ...

as a replacement and saved the choir stalls from Saint-Louis-du-Louvre which are still in place at l'Oratoire.

History

Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre

On 8 October 1164,

On 8 October 1164, Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, after intensifying conflict

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

with Henry II over his efforts to reduce the power of the church through the Constitutions of Clarendon

The Constitutions of Clarendon were a set of legislative procedures passed by Henry II of England in 1164. The Constitutions were composed of 16 articles and represent an attempt to restrict ecclesiastical privileges and curb the power of the Chur ...

, was put on trial and convicted of various offenses by Henry in Northampton Castle

Northampton Castle at Northampton, was one of the most famous Norman castles in England. The castle site was outside the western city gate, and defended on three sides by deep trenches. A branch of the River Nene provided a natural barrier on the ...

. Becket proceeded to flee to France where he was welcomed and hosted for six years by Louis VII

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

. Shortly after his return to England in 1170, Becket was famously murdered in Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

and subsequently canonized in 1173. In 1179, Louis VII travelled to Canterbury to pay his respects to the saint, making a donation of a gold chalice and an annual donation of 100 muids

Muids () is a commune in the Eure department in Normandy in northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in ...

(~3,400 gallons

The gallon is a unit of volume in imperial units and United States customary units. Three different versions are in current use:

*the imperial gallon (imp gal), defined as , which is or was used in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Austral ...

) of wine for the celebration of the annual feast.

Inspired by his brother's devotion, Robert of Dreux founded a new collegiate church, Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, in 1187, with endowment for four canons. After Robert's death, his wife, Agnès de Baudemont, obtained confirmation of the foundation of the church from Pope Clement III

Pope Clement III ( la, Clemens III; 1130 – 20 March 1191), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 December 1187 to his death in 1191. He ended the conflict between the Papacy and the city of Rome, by all ...

in 1189. Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

provided further confirmation in 1192 by means of letters-patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

with the great seal in green wax. A papal bull from Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

in 1199 took the church, its property and clergy, under the protection of the Pope. In 1428, John VI, Duke of Brittany

John V, sometimes numbered as VI, (24 December 1389 – 29 August 1442) bynamed John the Wise ( br, Yann ar Fur; french: Jean le Sage), was Duke of Brittany and Count of Montfort from 1399 to his death. His rule coincided with the height of th ...

endowed more prebends

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

for the church by donating the adjoining hotel, ''La Petite Bretagne'', on the condition that the canons pray for his family. This increased the number of canons to seven, to be chosen alternately by the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

and bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

.

Saint-Louis-du-Louvre

By 1739 the church had fallen into ruin and

By 1739 the church had fallen into ruin and Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

gave 50,000 crowns

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

for it to be rebuilt. During the demolition process a portion of the church was left for the continuing use of the chapter. While the canons were performing the office the remaining structure collapsed, burying them in the ruins. This accident led to the union of the chapter with that of the neighboring Saint-Nicolas-du-Louvre, which had also been founded by Robert of Dreux and had at various times previously been united with Saint-Thomas, and the rededication of the reconstructed church to Saint Louis in 1744. In 1749, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés () is a commune in Val-de-Marne

Val-de-Marne (, "Vale of the Marne") is a department of France located in the Île-de-France region. Named after the river Marne, it is situated in the Grand Paris metropolis to the southea ...

was also merged with the new congregation.

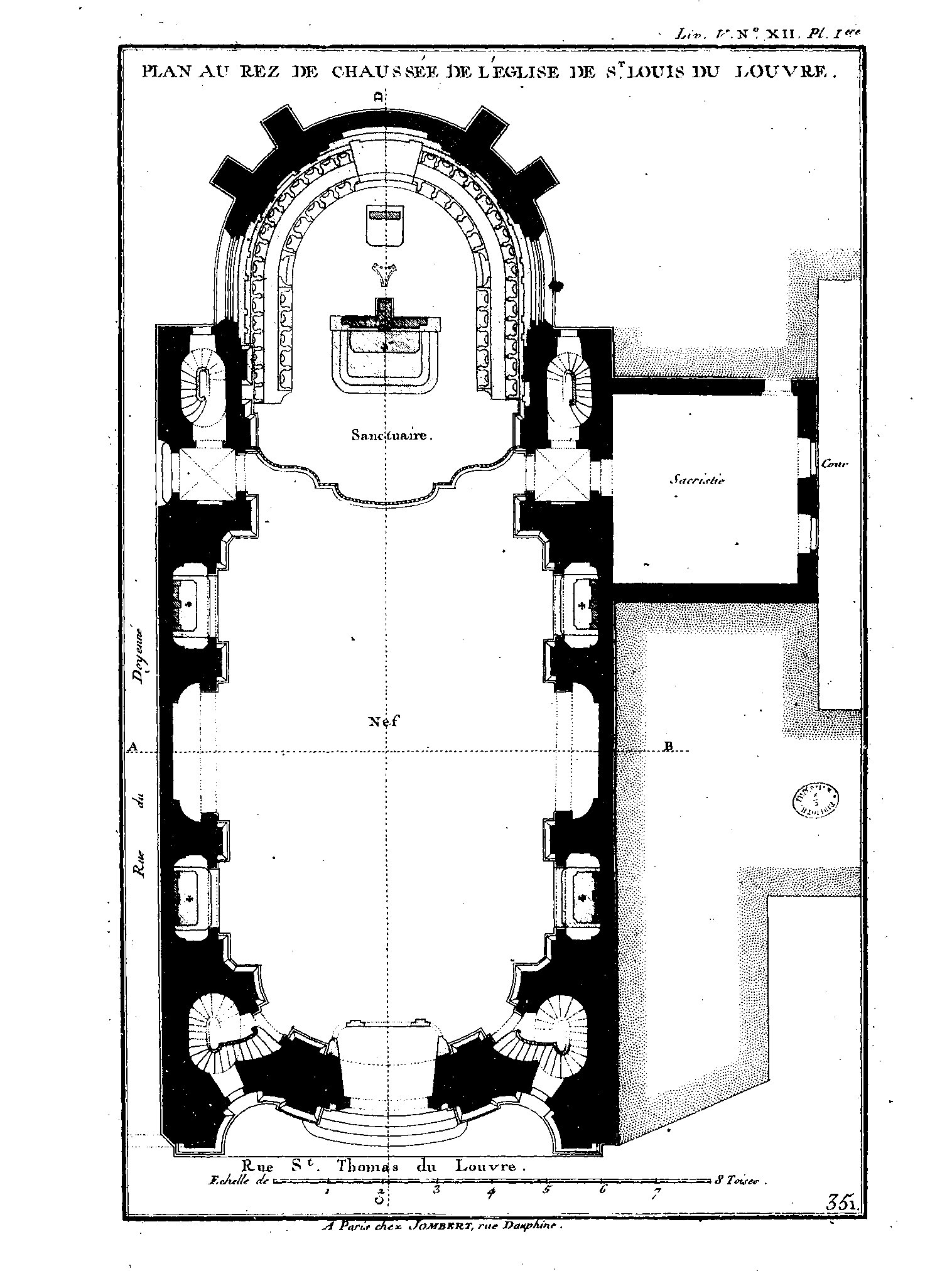

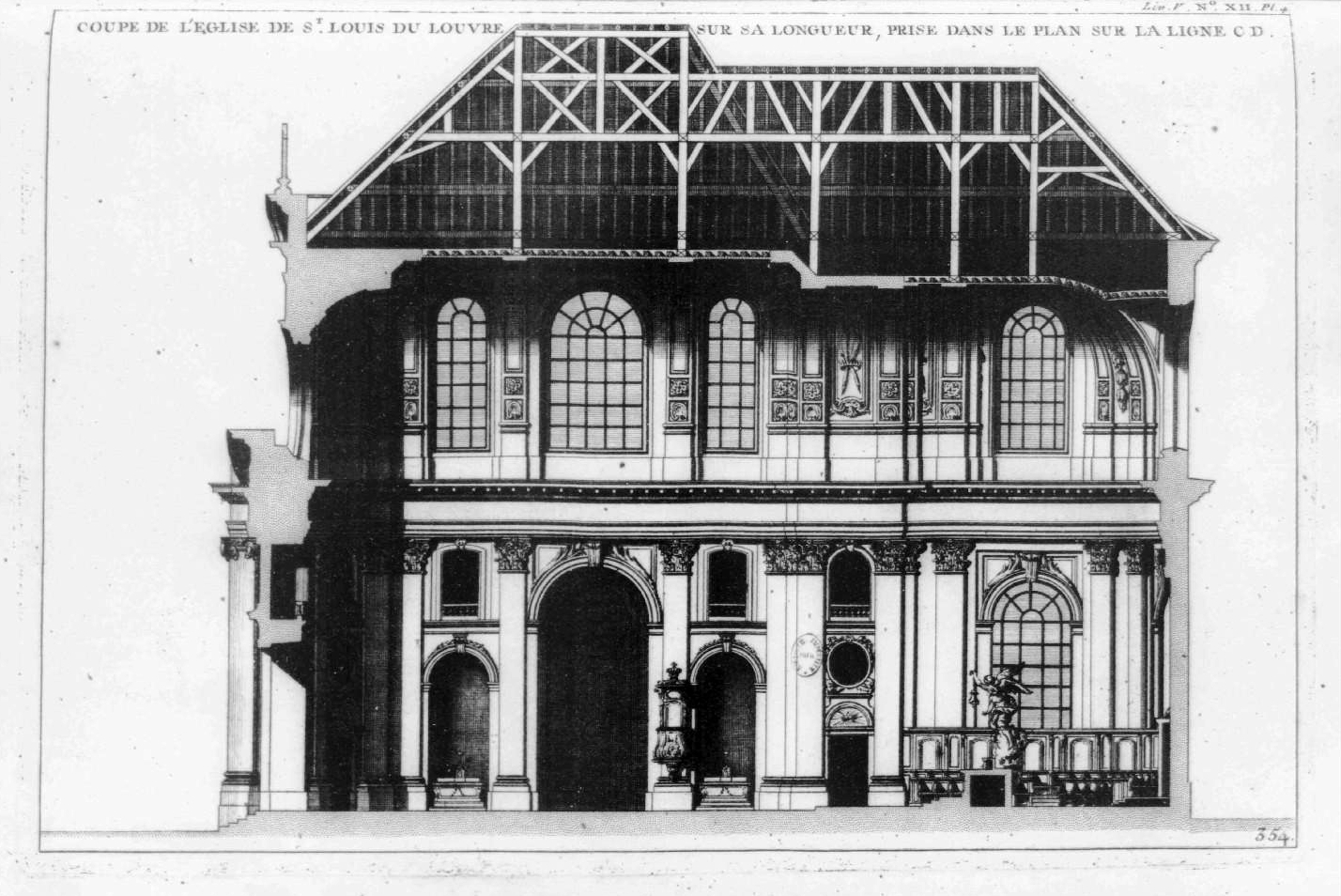

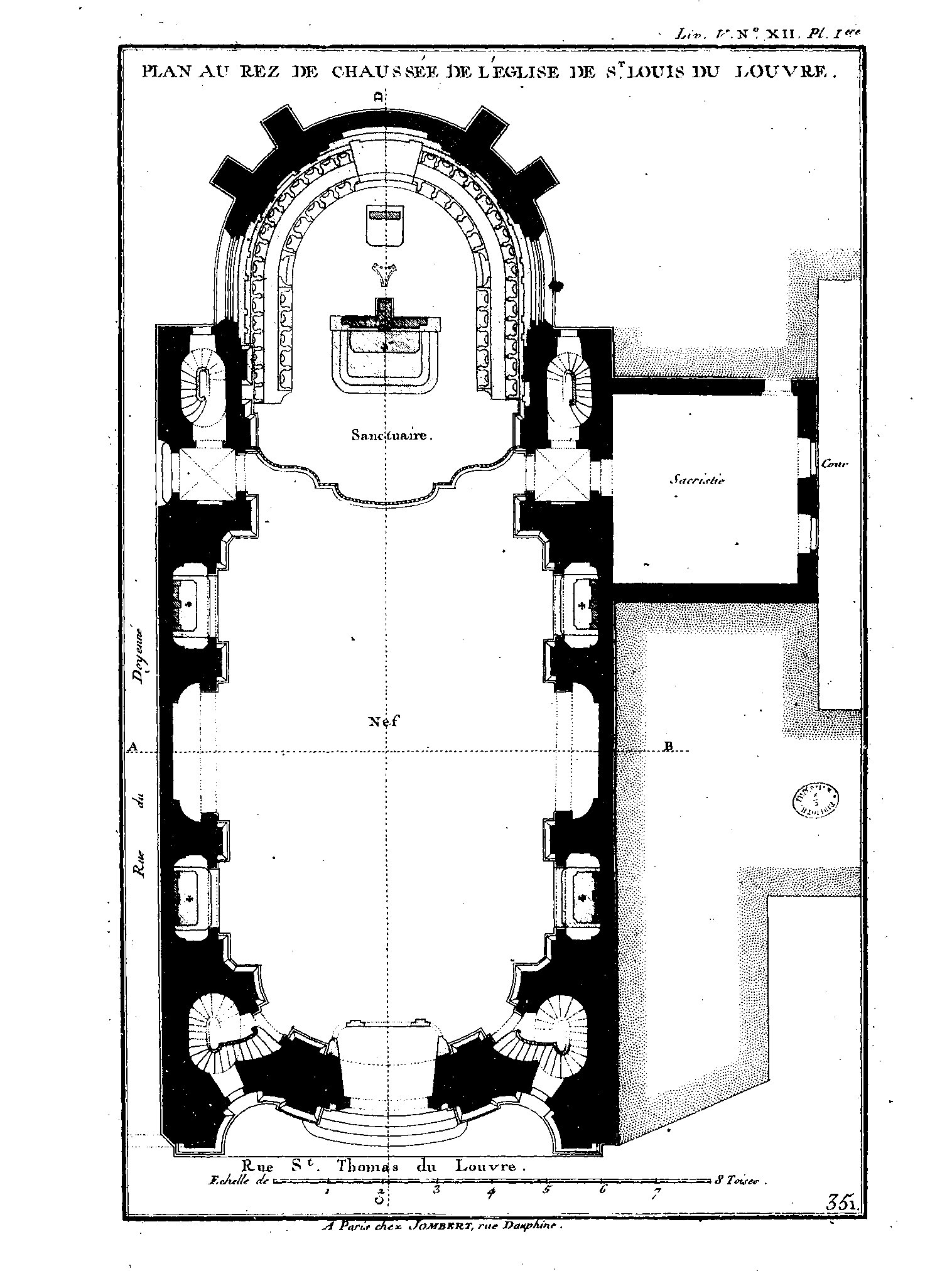

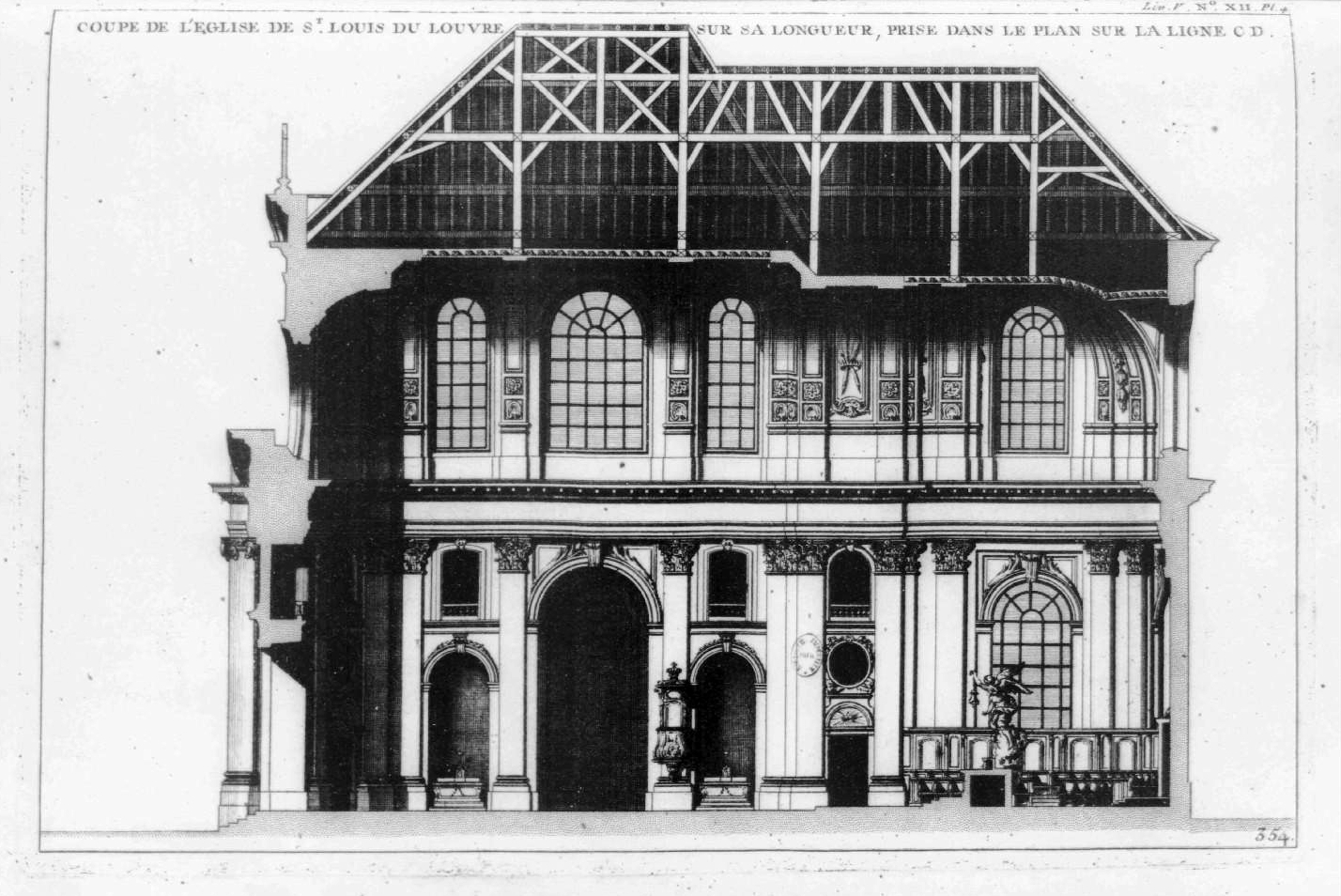

The new church was designed by Thomas Germain

Thomas Germain (1673–1748) was the pre-eminent Parisian silversmith of the Rococo.

The son of a Paris silversmith Pierre Germain (none of whose work survives) he did not at first train in the family workshop, but began as a painter, spending th ...

, known best for his work as a silversmith

A silversmith is a metalworker who crafts objects from silver. The terms ''silversmith'' and ''goldsmith'' are not exactly synonyms as the techniques, training, history, and guilds are or were largely the same but the end product may vary great ...

, and consisted of just a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and an apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

. The entrance of the church was in a circular projection decorated with Ionic pilasters

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wall ...

. The apse housed the choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

stalls of the canons surrounding the high altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

. The nave was decorated with Corinthian Corinthian or Corinthians may refer to:

*Several Pauline epistles, books of the New Testament of the Bible:

**First Epistle to the Corinthians

**Second Epistle to the Corinthians

**Third Epistle to the Corinthians (Orthodox)

*A demonym relating to ...

pilasters surmounted by an entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

. In the chapel of the Virgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

there was a sculpture of the Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ange ...

by Jean-Baptiste II Lemoyne

Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (15 February 1704 – 1778) was a French sculptor of the 18th century who worked in both the rococo and neoclassical style. He made monumental statuary for the Gardens of Versailles but was best known for his expressive p ...

. The church was also decorated with works by members of the families of painters, Coypel, Restout The Restout family was a French dynasty of painters from Normandy, including the painters:

* Marguerin Restout and his sons:

** Marc Restout (1616–1684) and his sons:

*** Jacques Restout (1650–1701)

*** Eustache Restout (1655–1743), also an ...

, and Van Loo Van Loo is a Dutch toponymic surname, meaning "from the forest clearing". People with this surname include:

;A family of painters :

*Jacob van Loo (1614–1670), Dutch painter

*Louis-Abraham van Loo (1653-1712), Dutch-born French painter, son o ...

. The building enjoyed a good reputation in the middle of the 18th century for its singular plan and rich internal decoration. However, the style of the exterior and portico came under some criticism.

When Cardinal Fleury

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

, the tutor and chief minister of Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

, died in 1743 the king decided that his mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

would be placed in Saint-Louis-du-Louvre. A competition was held for the commission to create the tomb, a landmark event in the history of 18th century French sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

due to its solicitation of public input. Philibert Orry, then the director of the Royal Buildings, solicited proposals from sculptors who were members of the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. Models for the tomb were offered by Nicolas-Sébastien Adam

Nicolas-Sébastien Adam (22 March 1705 – 27 March 1778), also called "Adam the Younger", was a French sculptor working in the Neoclassical style.David B. Morris, ''The Culture of Pain'' (University of California Press, 1991), p. 203. He was bor ...

, Edmé Bouchardon

Edmé Bouchardon (; 29 May 169827 July 1762) was a French sculptor best known for his neoclassical statues in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles, his medals, his equestrian statue of Louis XV of France for the Place de la Concorde (destroy ...

, Charles-François Ladette, Jean-Baptiste II Lemoyne, and Jean-Joseph Vinache

Jean-Joseph Vinache (1696 – 1 December 1754) was a French sculptor who served as the court sculptor to Augustus II, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony. Vinache's equestrian monument of Augustus, known as the "Gilded Horseman" (''Goldener Rei ...

. The wax maquettes of proposals were displayed at the Salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

for public response. Bouchardon won the competition though ultimately Lemoyne was given the commission by the family of Cardinal Fleury and the tomb remained unfinished at the time of the church's suppression. The church was also home to the tomb of its architect, Thomas Germain.

At the time of the French Revolution the church had a provost, a cantor

A cantor or chanter is a person who leads people in singing or sometimes in prayer. In formal Jewish worship, a cantor is a person who sings solo verses or passages to which the choir or congregation responds.

In Judaism, a cantor sings and lead ...

, and twenty canons with the provost, cantor and fifteen canons nominated by the archbishop, four by the Duke of Penthièvre

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

in this role as the Count of Brie

Brie (; ) is a soft cow's-milk cheese named after Brie, the French region from which it originated (roughly corresponding to the modern ''département'' of Seine-et-Marne). It is pale in color with a slight grayish tinge under a rind of white m ...

, and one by Les Gallichets. On 24 February 1790, the chapter declared to the revolutionary authorities annual revenues of 98,562 livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 gr ...

, a great sum for the time. On 11 December 1790, municipal officers came to the church to announce to the canons the suppression of their chapter and abolition of their titles. An inventory of the objects in the church was made and all the church's properties and possessions were turned over to the state.

Protestant Church

In 1791, at the behest of

In 1791, at the behest of Jean Sylvain Bailly

Jean Sylvain Bailly (; 15 September 1736 – 12 November 1793) was a French astronomer, mathematician, freemason, and political leader of the early part of the French Revolution. He presided over the Tennis Court Oath, served as the mayor of Par ...

, the mayor of Paris, and the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

, the empty Saint-Louis-du-Louvre was rented to the newly formed Reformed

Reform is beneficial change

Reform may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

*''Reforme'' ("Reforms"), initial name of the ...

congregation in Paris for the annual sum of 16,450 livres, with the first service held on Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

. In 1598, Protestant worship had been forbidden in Paris by the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

. In 1685, the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without s ...

made non-Catholic services illegal in all of France. This inaugurated a long period of persecution for French Protestants, though some in Paris were able to worship in the chapels of the Dutch and Swedish embassies.

The Edict of Tolerance

An edict of toleration is a declaration, made by a government or ruler, and states that members of a given religion will not be persecuted for engaging in their religious practices and traditions. The edict implies tacit acceptance of the religio ...

in 1787 gave Protestants legal status and a congregation was formed under the pastorship of Paul-Henri Marron

Paul-Henri Marron was the first Reformed tradition, Reformed pastor in Paris following the French Revolution. Born in the Netherlands to a Huguenot family, Marron first came to Paris as the chaplain of the Dutch embassy. Protestants in France ha ...

, who had been serving as the chaplain at the Dutch embassy. The congregation gained permission to worship openly in 1789 during the revolution and met in a variety of places including a wine shop before gaining permission to rent Saint-Louis-du-Louve, the first building dedicated to Protestant worship in the history of Paris. For the dedication of the new church, or ''temple'' as French Protestants referred to their buildings, Pastor Marron preached from the text, ''"Soyez joyeux dans l’espérance, patients dans l’affliction, persévérants dans la prière,"'' (be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer (Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

12:12)). When the mayor, Jean Bailly, attended in person on 13 October 1791 Marron chose the passage, ''"Vous connaissez la vérité et la vérité vous rendra libres,"'' (you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free

"The truth will set you free" (Latin: ''Vēritās līberābit vōs'' (biblical) or ''Vēritās vōs līberābit'' (common), Greek: ἡ ἀλήθεια ἐλευθερώσει ὑμᾶς, trans. ''hē alḗtheia eleutherṓsei hūmâs'') is a sta ...

(John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

8:32)).

As the revolution became increasingly hostile to Christianity, Marron was arrested on 21 September 1793. He was released and then rearrested and released once more, having made the concession of having services once every ten days according to the revolutionary calendar instead of on Sundays. Marron was once more arrested in June 1794 for continuing to marry and baptize

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation and Adoption ...

in secret after Christian practice had been banned by Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

in favor of the Cult of the Supreme Being

The Cult of the Supreme Being (french: Culte de l'Être suprême) was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic and a re ...

. He was freed from prison only by the fall of Robespierre.

In the Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace-Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation b ...

, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

came to an agreement with Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

to reconcile the Catholic church to the French state. The concordat also led to official recognition of, and state control over, other religious groups including Protestants. As a result, three former Catholic churches were dedicated for the use of reformed believers in Paris, Sainte-Marie-des-Anges, the chapel of the Pentemont Abbey

Pentemont Abbey (french: Abbaye de Penthemont, ''Pentemont'', ''Panthemont'' or ''Pantemont'') is a set of 18th and 19th century buildings at the corner of Rue de Grenelle and Rue de Bellechasse in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. The abbey was ...

, and Saint-Louis-du-Louvre. In 1806 however, Napoleon decreed an expansion of the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

that would require the demolition of all existing structures between the Louvre and the Tuileries

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

Palace including the church of Saint-Louis. As a replacement the Reformed congregation was given the Oratoire du Louvre

The Temple protestant de l'Oratoire du Louvre, also Église réformée de l'Oratoire du Louvre, is a historic Protestant church located at 145 rue Saint-Honoré – 160 rue de Rivoli in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, across the street from the L ...

, which had also been suppressed in the Revolution. The choir and some of the other woodwork was preserved and can be seen in the Oratoire, including the ''misericorde'' seats in the choir stalls that enabled the canons to rest while standing. While most of the church was demolished in 1811, a portion remained standing until the construction of the Denon wing of the Louvre in 1850.

References

External links

An article on the church's tombs

{{Authority control Roman Catholic churches in the 1st arrondissement of Paris Reformed churches in Paris Former collegiate churches Destroyed churches in France Former buildings and structures in Paris Buildings and structures demolished in 1811