Sagan standard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sagan standard is a

The Sagan standard is a

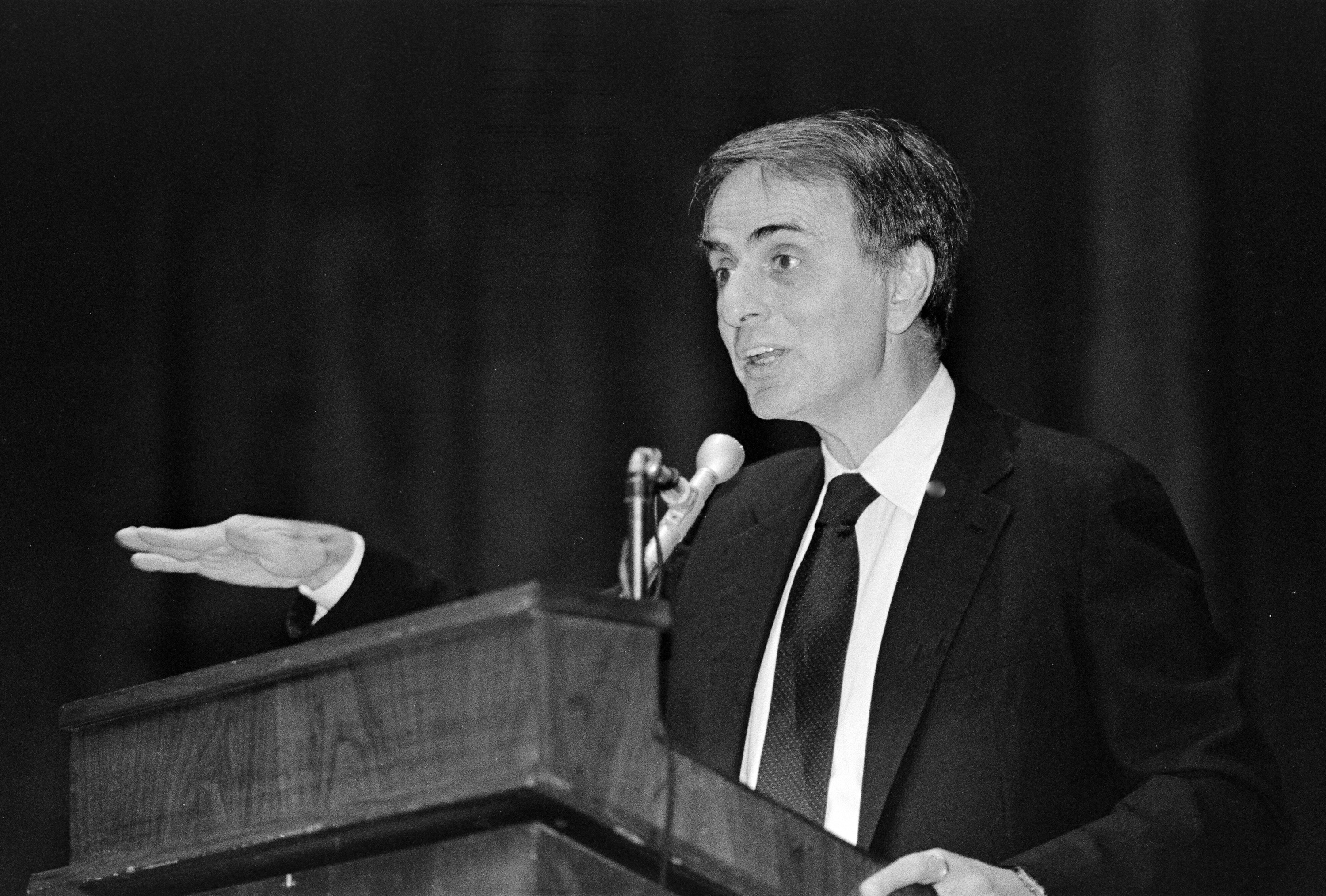

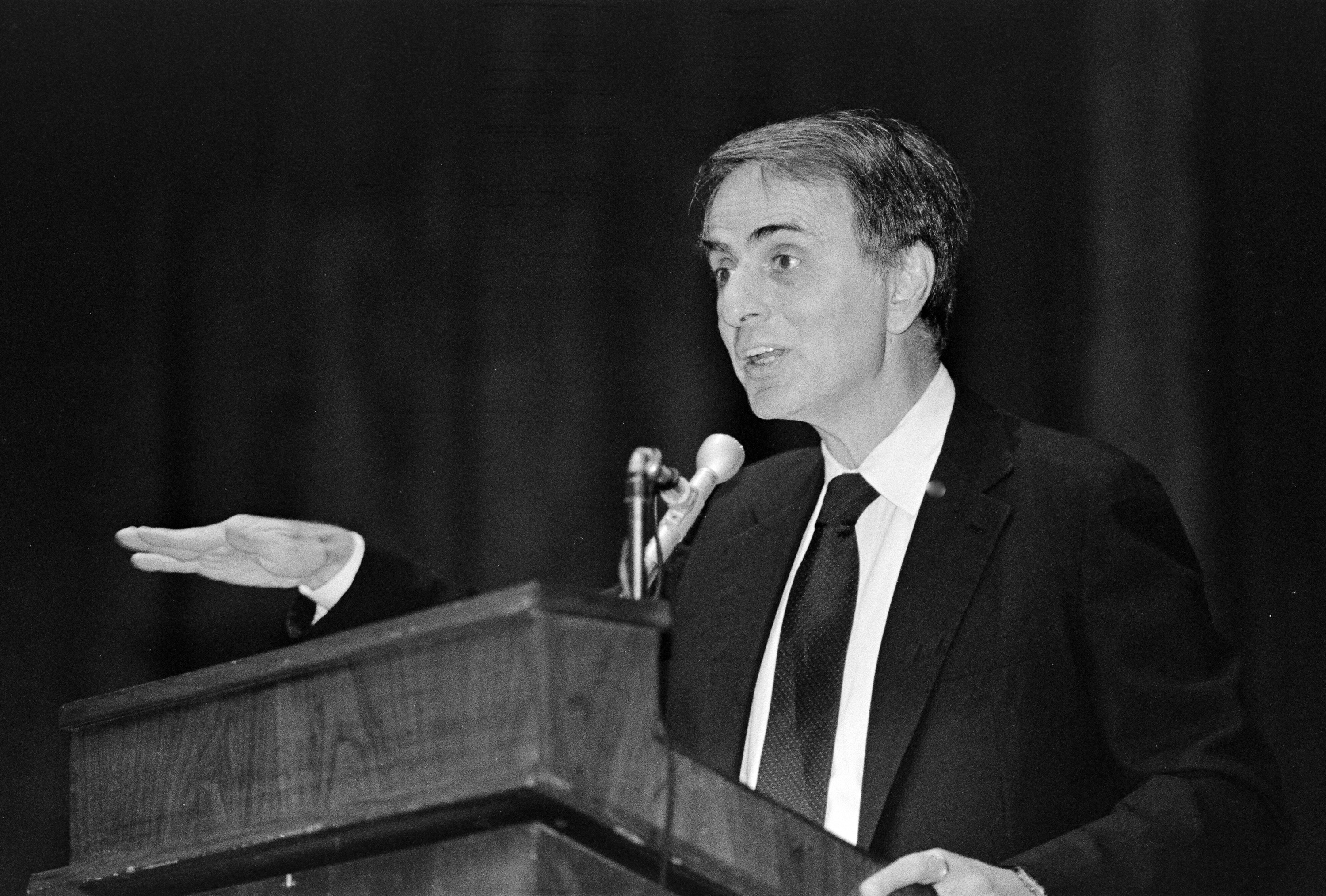

U.S. Library of Congress image

The Sagan standard is a

The Sagan standard is a neologism

A neologism Greek νέο- ''néo''(="new") and λόγος /''lógos'' meaning "speech, utterance"] is a relatively recent or isolated term, word, or phrase that may be in the process of entering common use, but that has not been fully accepted int ...

abbreviating the aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by t ...

that "''extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence''" (ECREE). It is named after science communicator

Science communication is the practice of informing, educating, raising awareness of science-related topics, and increasing the sense of wonder about scientific discoveries and arguments. Science communicators and audiences are ambiguously def ...

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ...

who used the exact phrase on his television program ''Cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

''.

Similar statements were previously made by figures such as Théodore Flournoy

Théodore Flournoy (15 August 1854 – 5 November 1920) was a Swiss professor of psychology at the University of Geneva and author of books on parapsychology and spiritism. He studied a wide variety of subjects before he devoted his life to psych ...

in 1899, Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

in 1814, and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

in 1808. The formulation "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof" was used just two years prior to Sagan, by sociologist Marcello Truzzi

Marcello Truzzi (September 6, 1935 – February 2, 2003) was a professor of sociology at New College of Florida and later at Eastern Michigan University, founding co-chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Para ...

, in 1978.

Application

The Sagan standard, according to Tressoldi (2011), "is at the heart of thescientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

, and a model for critical thinking

Critical thinking is the analysis of available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments to form a judgement. The subject is complex; several different definitions exist, which generally include the rational, skeptical, and unbiased an ...

, rational thought

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an abili ...

and skepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the p ...

everywhere".

ECREE is related to Occam's razor

Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, or Ocham's razor ( la, novacula Occami), also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony ( la, lex parsimoniae), is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond neces ...

in the sense that according to such a heuristic

A heuristic (; ), or heuristic technique, is any approach to problem solving or self-discovery that employs a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational, but is nevertheless sufficient for reaching an immediat ...

, simpler explanations are preferred to more complicated ones. Only in situations where extraordinary evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, eviden ...

exists would an extraordinary claim be the simplest explanation. A routinized form of this appears in hypothesis testing

A statistical hypothesis test is a method of statistical inference used to decide whether the data at hand sufficiently support a particular hypothesis.

Hypothesis testing allows us to make probabilistic statements about population parameters.

...

where the hypothesis that there is no evidence for the proposed phenomenon, what is known as the "null hypothesis

In scientific research, the null hypothesis (often denoted ''H''0) is the claim that no difference or relationship exists between two sets of data or variables being analyzed. The null hypothesis is that any experimentally observed difference is d ...

", is preferred. The formal argument involves assigning a stronger Bayesian prior to the acceptance of the null hypothesis as opposed to its rejection.

There are no concrete parameters as to what constitutes "extraordinary claims", which raises the issue of whether the standard is subjective. According to Tressoldi this problem is less apparent in clinical medicine and psychology where statistical results can establish the strength of evidence In biostatistics, Strength of evidence is the strength of a conducted study that can be assessed in health care interventions, e.g. to identify effective health care programs and evaluate the quality of the research in health care. It can be graded ...

.

Some would argue that evidence cannot be extraordinary. The definition of evidence, points to the available body of facts or information. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary scrutiny.

History

The aphorism was made popular by astronomerCarl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ...

who used it in the 1980 television show ''Cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

'' in reference to claims about aliens visiting Earth. Sagan made similar statements in a 1977 interview in ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', and his 1979 book ''Broca's Brain

''Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science'' is a 1979 book by the astrophysicist Carl Sagan. Its chapters were originally articles published between 1974 and 1979 in various magazines, including ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ''The New Re ...

''; Marcello Truzzi

Marcello Truzzi (September 6, 1935 – February 2, 2003) was a professor of sociology at New College of Florida and later at Eastern Michigan University, founding co-chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Para ...

did likewise in '' Parapsychology Review'' in 1975 and ''Zetetic Scholar'' in 1978. Two 1978 articles, one in '' U.S. News & World Report'' and another by Koneru Ramakrishna Rao

Koneru Ramakrishna Rao (4 October 1932 – 9 November 2021) was an Indian philosopher who served as Chancellor of GITAM (Deemed To Be University), and as Chairman of GITAM school of Gandhian Studies, psychologist, parapsychologist, educationis ...

in the '' Journal of Parapsychology'' both quote physicist Philip Abelson

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, then the editor of ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

'', using the same phrase.

Others had earlier put forward very similar ideas. Quote Investigator cites similar statements from Benjamin Bayly

Benjamin Baily (1671–1720), was an English divine.

Life

Bayly matriculated at Oxford of St. Edmund's Hall on 20 March 1688, and graduated B.A. of Wadham College on 15 October 1692. He took the degree of M.A. on 30 October 1695. He was recto ...

(in 1708), Arthur Ashley Sykes

Arthur Ashley Sykes (1684–1756) was an Anglican religious writer, known as an inveterate controversialist. Sykes was a latitudinarian of the school of Benjamin Hoadly, and a friend and student of Isaac Newton.

Life

Sykes was born in London i ...

(1740), Beilby Porteus

Beilby Porteus (or Porteous; 8 May 1731 – 13 May 1809), successively Bishop of Chester and of London, was a Church of England reformer and a leading abolitionist in England. He was the first Anglican in a position of authority to seriously ch ...

(1800), Elihu Palmer

Elihu Palmer (1764 – April 7, 1806) was an author and advocate of deism in the early days of the United States.

Life

Elihu Palmer was born in Canterbury, Connecticut in 1764. He studied to be a Presbyterian minister at Dartmouth College, where ...

(1804), and William Craig Brownlee (1824), all of whom used it in the context of the extraordinary claims of Christian theology and the putative extraordinary evidence supplied by the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts o ...

. Quote Investigator also cites Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

in essays (1810 and 1814) on the stability of the Solar System

The stability of the Solar System is a subject of much inquiry in astronomy. Though the planets have been stable when historically observed, and will be in the short term, their weak gravitational effects on one another can add up in unpredictable ...

, and Joseph Rinn

Joseph Francis Rinn (1868–1952) was an American magician and skeptic of paranormal phenomena.

Career

Rinn grew up in New York City. He coached Harry Houdini as a teenager in running at the Pastime Athletic Club. He remained a friend to Houdin ...

(1906), a skeptic

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then th ...

of the paranormal

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. No ...

. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

in an 1808 letter expresses contemporary skepticism of meteorites thus: "A thousand phenomena present themselves daily which we cannot explain, but where facts are suggested, bearing no analogy with the laws of nature as yet known to us, their verity needs proofs proportioned to their difficulty." Letter to Daniel Salmon on 15 February 1808 discussing the nature and origin of meteoritesU.S. Library of Congress image

See also

*Burden of proof (philosophy)

The burden of proof (Latin: ''onus probandi'', shortened from ''Onus probandi incumbit ei qui dicit, non ei qui negat'') is the obligation on a party in a dispute to provide sufficient warrant for its position.

Holder of the burden

When two par ...

*Epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

*Hitchens's razor

Hitchens's razor is an epistemological razor (a general rule for rejecting certain knowledge claims) that states "what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." The razor was created by and named after author and ...

*Logical positivism

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, is a movement in Western philosophy whose central thesis was the verification principle (also known as the verifiability criterion of ...

*Razor (philosophy)

In philosophy, a razor is a principle or rule of thumb that allows one to eliminate ("shave off") unlikely explanations for a phenomenon, or avoid unnecessary actions.

Razors include:

*Occam's razor: Simpler explanations are more likely to be c ...

*Theory of justification

Justification (also called epistemic justification) is the property of belief that qualifies it as knowledge rather than mere opinion. Epistemology is the study of reasons that someone holds a rationally admissible belief (although the term is a ...

References

{{Carl Sagan Adages Carl Sagan Epistemology