Saga (Kyoto District) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sagas are

Norse sagas are generally classified as follows.

Norse sagas are generally classified as follows.

Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions and much research has focused on what is real and what is fiction within each tale. The accuracy of the sagas is often hotly disputed.

Most of the medieval manuscripts which are the earliest surviving witnesses to the sagas were taken to

Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions and much research has focused on what is real and what is fiction within each tale. The accuracy of the sagas is often hotly disputed.

Most of the medieval manuscripts which are the earliest surviving witnesses to the sagas were taken to

Bibliography of Saga Translations

The Skaldic Project, An international project to edit the corpus of medieval Norse-Icelandic skaldic poetry

Other: * Clover, Carol J. et al. ''Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A critical guide'' (University of Toronto Press, 2005) * Gade, Kari Ellen (ed.) ''Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 2 From c. 1035 to c. 1300'' (Brepols Publishers. 2009) * Gordon, E. V. (ed) ''An Introduction to Old Norse'' (Oxford University Press; 2nd ed. 1981) * Jakobsson, Armann; Fredrik Heinemann (trans) ''A Sense of Belonging: Morkinskinna and Icelandic Identity, c. 1220'' (Syddansk Universitetsforlag. 2014) * Jakobsson, Ármann ''Icelandic sagas'' (The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages 2nd Ed. Robert E. Bjork. 2010) * McTurk, Rory (ed) ''A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005) * Ross, Margaret Clunies ''The Cambridge Introduction to the Old Norse-Icelandic Saga'' (Cambridge University Press, 2010) * Thorsson, Örnólfur ''The Sagas of Icelanders'' (Penguin. 2001) * Whaley, Diana (ed.) ''Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 1 From Mythical Times to c. 1035'' (Brepols Publishers. 2012)

Icelandic Saga Database

– The Icelandic sagas in the original old Norse along with translations into many languages

Old Norse Prose and Poetry

{{Authority control Medieval literature Sources of Norse mythology Icelandic literature North Germanic languages Old Norse literature

prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the ...

stories and histories, composed in Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

.

The most famous saga-genre is the ''Íslendingasögur

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early e ...

'' (sagas concerning Icelanders), which feature Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

voyages, migration to Iceland, and feuds between Icelandic families. However, sagas' subject matter is diverse, including pre-Christian Scandinavian legends; saints and bishops both from Scandinavia and elsewhere; Scandinavian kings and contemporary Icelandic politics; and chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

s either translated from Continental European languages or composed locally.

Sagas originated in the Middle Ages, but continued to be composed in the ensuing centuries. Whereas the dominant language of history-writing in medieval Europe was Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, sagas were composed in the vernacular: Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

and its later descendants, primarily Icelandic.

While sagas are written in prose, they share some similarities with epic poetry

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

, and often include stanzas or whole poems in alliterative verse

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of ...

embedded in the text.

Etymology and meaning of ''saga''

The main meanings of theOld Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

word ''saga'' (plural ''sǫgur'') are 'what is said, utterance, oral account, notification' and the sense used in this article: '(structured) narrative, story (about somebody)'. It is cognate with the English words ''say'' and ''saw

A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge. It is used to cut through material, very often wood, though sometimes metal or stone. The cut is made by placing the toothed edge against the material and mov ...

'' (in the sense 'a saying', as in ''old saw''), and the German ''Sage''; but the modern English term ''saga'' was borrowed directly into English from Old Norse by scholars in the eighteenth century to refer to Old Norse prose narratives.

The word continues to be used in this sense in the modern Scandinavian languages: Icelandic ''saga'' (plural ''sögur''), Faroese '' søga'' (plural ''søgur''), Norwegian '' soge'' (plural ''soger''), Danish ''saga'' (plural ''sagaer''), and Swedish ''saga'' (plural ''sagor''). It usually also has wider meanings such as 'history', 'tale', and 'story'. It can also be used of a genre of novels telling stories spanning multiple generations, or to refer to saga-inspired fantasy fiction. Swedish '' folksaga'' means folk tale or fairy tale, while ''konstsaga'' is the Swedish term for a fairy tale by a known author, such as Hans Christian Andersen. In Swedish historiography, the term ''sagokung'', "saga king", is intended to be ambiguous, as it describes the semi-legendary kings of Sweden

The legendary kings of Sweden () according to legends were rulers of Sweden and the Swedes who preceded Eric the Victorious and Olof Skötkonung, the earliest reliably attested Swedish kings. Though the stories of some of the kings may be embel ...

, who are known only from unreliable sources.

Genres

Norse sagas are generally classified as follows.

Norse sagas are generally classified as follows.

Kings' sagas

Kings' sagas

Kings' sagas ( is, konungasögur, nn, kongesoger, -sogor, nb, kongesagaer) are Old Norse sagas which principally tell of the lives of semi-legendary and legendary (mythological, fictional) Nordic kings, also known as saga kings. They were comp ...

(''konungasögur'') are of the lives of Scandinavian kings. They were composed in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. A pre-eminent example is ''Heimskringla

''Heimskringla'' () is the best known of the Old Norse kings' sagas. It was written in Old Norse in Iceland by the poet and historian Snorre Sturlason (1178/79–1241) 1230. The name ''Heimskringla'' was first used in the 17th century, derive ...

'', probably compiled and composed by Snorri Sturluson. These sagas frequently quote verse, invariably occasional and praise poetry in the form of skaldic verse

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionally ...

.

Sagas of Icelanders and short tales of Icelanders

TheIcelanders' sagas

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early e ...

(''Íslendingasögur''), sometimes also called "family sagas" in English, are purportedly (and sometimes actually) stories of real events, which usually take place from around the settlement of Iceland in the 870s to the generation or two following the conversion of Iceland to Christianity in 1000. They are noted for frequently exhibiting a realistic style.Vésteinn Ólason, 'Family Sagas', in ''A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture'', ed. by Rory Mcturk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 101–18. It seems that stories from these times were passed on in oral form until they eventually were recorded in writing as ''Íslendingasögur'', whose form was influenced both by these oral stories and by literary models in both Old Norse and other languages. The majority — perhaps two thirds of the medieval corpus — seem to have been composed in the thirteenth century, with the remainder in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. These sagas usually span multiple generations and often feature everyday people (e.g. ''Bandamanna saga Bandamanna saga (Old Norse: ; Modern Icelandic: ) is one of the sagas of Icelanders. It is the only saga in this category that takes place exclusively after the adoption of Christianity in the year 1000.

The story tells about the father and son, Of ...

'') and larger-than-life characters (e.g. ''Egils saga

''Egill's Saga'' or ''Egil's saga'' ( non, Egils saga ; ) is an Icelandic saga (family saga) on the lives of the clan of Egill Skallagrímsson (Anglicised as Egill Skallagrimsson), an Icelandic farmer, viking and skald. The saga spans the year ...

''). Key works of this genre have been viewed in modern scholarship as the highest-quality saga-writing. While primarily set in Iceland, the sagas follow their characters' adventures abroad, for example in other Nordic countries, the British Isles, northern France and North America. Some well-known examples include ''Njáls saga

''Njáls saga'' ( ), also ''Njála'' ( ), ''Brennu-Njáls saga'' ( ) or ''"The Story of Burnt Njáll"'', is a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga that describes events between 960 and 1020.

The saga deals with a process of blood feuds in the I ...

'', '' Laxdæla saga'' and ''Grettis saga

''Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar'' (modern , reconstructed ), also known as ''Grettla'', ''Grettir's Saga'' or ''The Saga of Grettir the Strong'', is one of the Icelanders' sagas. It details the life of Grettir Ásmundarson, a bellicose Icelandic out ...

''.

The material of the short tales of Icelanders

Short may refer to:

Places

* Short (crater), a lunar impact crater on the near side of the Moon

* Short, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Short, Oklahoma, a census-designated place

People

* Short (surname)

* List of people known as ...

(''þættir'' or ''Íslendingaþættir'') is similar to ''Íslendinga sögur'', in shorter form, often preserved as episodes about Icelanders in the kings' sagas.

Like kings' sagas, when sagas of Icelanders quote verse, as they often do, it is almost invariably skaldic verse.

Contemporary sagas

Contemporary sagas (''samtíðarsögur'' or ''samtímasögur'') are set in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iceland, and were written soon after the events they describe. Most are preserved in the compilation '' Sturlunga saga'', from around 1270–80, though some, such as '' Arons saga Hjörleifssonar'' are preserved separately. The verse quoted in contemporary sagas is skaldic verse. According to historian Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, "Scholars generally agree that the contemporary sagas are rather reliable sources, based on the short time between the events and the recording of the sagas, normally twenty to seventy years... The main argument for this view on the reliability of these sources is that the audience would have noticed if the saga authors were slandering and not faithfully portraying the past."Legendary sagas

Legendary saga

A legendary saga or ''fornaldarsaga'' (literally, "story/history of the ancient era") is a Norse saga that, unlike the Icelanders' sagas, takes place before the settlement of Iceland.The article ''Fornaldarsagor'' in ''Nationalencyklopedin'' (1991 ...

s (''fornaldarsögur'') blend remote history, set on the Continent before the settlement of Iceland, with myth or legend. Their aim is usually to offer a lively narrative and entertainment. They often portray Scandinavia's pagan past as a proud and heroic history. Some legendary sagas quote verse — particularly '' Vǫlsunga saga'' and '' Heiðreks saga'' — and when they do it is invariably Eddaic verse.

Some legendary sagas overlap generically with the next category, chivalric sagas.Matthew, Driscoll, 'Late Prose Fiction (''Lygisögur'')', in ''A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture'', ed. by Rory McTurk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 190–204.

Chivalric sagas

Chivalric sagas (''riddarasögur'') are translations of Latin pseudo-historical works and French chansons de geste as well as Icelandic compositions in the same style. Norse translations of Continental romances seem to have begun in the first half of the thirteenth century; Icelandic writers seem to have begun producing their own romances in the late thirteenth century, with production peaking in the fourteenth century and continuing into the nineteenth. While often translated from verse, sagas in this genre almost never quote verse, and when they do it is often unusual in form: for example, '' Jarlmanns saga ok Hermanns'' contains the first recorded quotation of a refrain from an Icelandic dance-song, and a metrically irregularriddle

A riddle is a statement, question or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: ''enigmas'', which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or allegorical language that requ ...

in '' Þjalar-Jóns saga''.

Saints' and bishops' sagas

Saints' sagas (''heilagra manna sögur'') andbishops' sagas

The bishops' saga (Old Norse and modern Icelandic ''biskupasaga'', modern Icelandic plural ''biskupasögur'', Old Norse plural ''biskupasǫgur'') is a genre of medieval Icelandic sagas, mostly thirteenth- and earlier fourteenth-century prose histo ...

(''biskupa sögur'') are vernacular Icelandic translations and compositions, to a greater or lesser extent influenced by saga-style, in the widespread genres of hagiography and episcopal biographies. The genre seems to have begun in the mid-twelfth century.

History

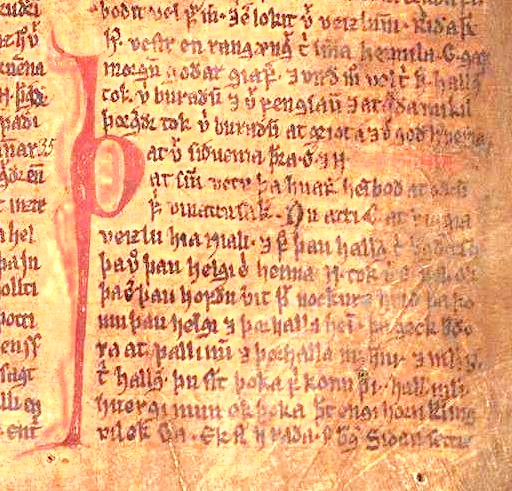

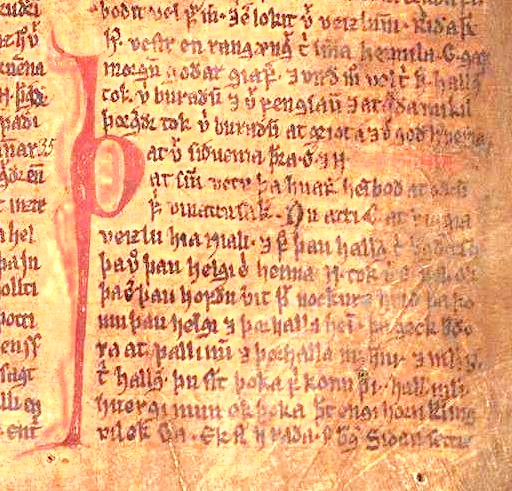

Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions and much research has focused on what is real and what is fiction within each tale. The accuracy of the sagas is often hotly disputed.

Most of the medieval manuscripts which are the earliest surviving witnesses to the sagas were taken to

Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions and much research has focused on what is real and what is fiction within each tale. The accuracy of the sagas is often hotly disputed.

Most of the medieval manuscripts which are the earliest surviving witnesses to the sagas were taken to Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

and Sweden in the seventeenth century, but later returned to Iceland. Classical sagas were composed in the thirteenth century. Scholars once believed that these sagas were transmitted orally from generation to generation until scribes wrote them down in the thirteenth century. However, most scholars now believe the sagas were conscious artistic creations, based on both oral and written tradition. A study focusing on the description of the items of clothing mentioned in the sagas concludes that the authors attempted to create a historic "feel" to the story, by dressing the characters in what was at the time thought to be "old fashioned clothing". However, this clothing is not contemporary with the events of the saga as it is a closer match to the clothing worn in the 12th century. It was only recently (start of 20th century) that the tales of the voyages to North America (modern day Canada) were authenticated.

Most sagas of Icelanders take place in the period 930–1030, which is called '' söguöld'' (Age of the Sagas) in Icelandic history. The sagas of kings, bishops, contemporary sagas have their own time frame. Most were written down between 1190 and 1320, sometimes existing as oral traditions long before, others are pure fiction, and for some we do know the sources: the author of King Sverrir's saga had met the king and used him as a source.

While sagas are generally anonymous, a distinctive literary movement in the 14th century involves sagas, mostly on religious topics, with identifiable authors and a distinctive Latinate style. Associated with Iceland's northern diocese of Hólar

Hólar (; also Hólar í Hjaltadal ) is a small community in the Skagafjörður district of northern Iceland.

Location

Hólar is in the Hjaltadalur valley, some from the national capital of Reykjavík. It has a population of around 100. It is th ...

, this movement is known as the North Icelandic Benedictine School

The North Icelandic Benedictine School (''Norðlenski Benediktskólinn'') is a fourteenth-century Icelandic literary movement, the lives, activities, and relationships of whose members are attested particularly by ''Laurentius Saga, Laurentius sag ...

(''Norðlenski Benediktskólinn'').

The vast majority of texts referred to today as "sagas" were composed in Iceland. One exception is ''Þiðreks saga

''Þiðreks saga af Bern'' ('the saga of Þiðrekr of Bern', also ''Þiðrekssaga'', ''Þiðriks saga'', ''Niflunga saga'' or ''Vilkina saga'', with Anglicisations including ''Thidreksaga'') is an Old Norse chivalric saga centering the character ...

'', translated/composed in Norway; another is '' Hjalmars och Hramers saga'', a post-medieval forgery composed in Sweden. While the term ''saga'' is usually associated with medieval texts, sagas — particularly in the legendary and chivalric saga genres — continued to be composed in Iceland on the pattern of medieval texts into the nineteenth century.

Explanations for saga writing

Icelanders produced a high volume of literature relative to the size of the population. Historians have proposed various theories for the high volume of saga writing. Early, nationalist historians argued that the ethnic characteristics of the Icelanders were conducive to a literary culture, but these types of explanations have fallen out of favor with academics in modern times. It has also been proposed that the Icelandic settlers were so prolific at writing in order to capture their settler history. Historian Gunnar Karlsson does not find that explanation reasonable though, given that other settler communities have not been as prolific as the early Icelanders were. Pragmatic explanations were once also favoured: it has been argued that a combination of readily available parchment (due to extensive cattle farming and the necessity ofculling

In biology, culling is the process of segregating organisms from a group according to desired or undesired characteristics. In animal breeding, it is the process of removing or segregating animals from a breeding stock based on a specific tr ...

before winter) and long winters encouraged Icelanders to take up writing.

More recently, Icelandic saga-production has been seen as motivated more by social and political factors.

The unique nature of the political system of the Icelandic Commonwealth created incentives for aristocrats to produce literature, offering a way for chieftains to create and maintain social differentiation between them and the rest of the population. Gunnar Karlsson and Jesse Byock

Jesse L. Byock (born 1945) is Professor of Old Norse and Medieval Scandinavian Studies in the Scandinavian Section at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University. An archaeologist and specia ...

argued that the Icelanders wrote the Sagas as a way to establish commonly agreed norms and rules in the decentralized Icelandic Commonwealth by documenting past feuds, while Iceland's peripheral location put it out of reach of the continental kings of Europe and that those kings could therefore not ban subversive forms of literature. Because new principalities lacked internal cohesion, a leader typically produced Sagas "to create or enhance amongst his subjects or followers a feeling of solidarity and common identity by emphasizing their common history and legends". Leaders from old and established principalities did not produce any Sagas, as they were already cohesive political units.

Later (late thirteenth- and fourteenth-century) saga-writing was motivated by the desire of the Icelandic aristocracy to maintain or reconnect links with the Nordic countries by tracing the ancestry of Icelandic aristocrats to well-known kings and heroes to which the contemporary Nordic kings could also trace their origins.

Editions and translations

The corpus of Old Norse sagas is gradually being edited in theÍslenzk fornrit

Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, or The Old Icelandic Text Society is a text publication society. It is the standard publisher of Old Icelandic texts (such as the Sagas of Icelanders, Kings' sagas and bishops' sagas) with thorough introductions and c ...

series, which covers all the ''Íslendingasögur'' and a growing range of other ones. Where available, the Íslenzk fornrit edition is usually the standard one. The standard edition of most of the chivalric sagas composed in Iceland is by Agnete Loth.

A list, intended to be comprehensive, of translations of Icelandic sagas is provided by the National Library of Iceland

Landsbókasafn Íslands – Háskólabókasafn ( Icelandic: ; English: ''The National and University Library of Iceland'') is the national library of Iceland which also functions as the university library of the University of Iceland. The librar ...

'Bibliography of Saga Translations

Popular culture

Many modern artists working in different creative fields have drawn inspiration from the sagas. Among some well-known writers, for example, who adapted saga narratives in their works arePoul Anderson

Poul William Anderson (November 25, 1926 – July 31, 2001) was an American fantasy and science fiction author who was active from the 1940s until the 21st century. Anderson wrote also historical novels. His awards include seven Hugo Awards and ...

, Laurent Binet

Laurent Binet (born 19 July 1972) is a French writer and university lecturer. His work focuses on the modern political scene in France.

Biography

The son of a historian,Valérie Trierweiler, October 18, 2010"Laurent Binet, retour sur un succès" ...

, Margaret Elphinstone, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué

Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte, Baron Fouqué (); (12 February 1777 – 23 January 1843) was a German writer of the Romantic style.

Biography

He was born at Brandenburg an der Havel, of a family of French Huguenot origin, as evidenced in ...

, Gunnar Gunnarsson

Gunnar Gunnarsson (18 May 1889 – 21 November 1975) was an Icelandic author who wrote mainly in Danish. He grew up, in considerable poverty, on Valþjófsstaður in Fljótsdalur valley and on Ljótsstaðir in Vopnafjörður. During ...

, Henrik Ibsen, Halldór Laxness, Ottilie Liljencrantz, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

, George Mackay Brown

George Mackay Brown (17 October 1921 – 13 April 1996) was a Scottish poet, author and dramatist with a distinctly Orcadian character. He is widely regarded as one of the great Scottish poets of the 20th century.

Biography Early life and caree ...

, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, Adam Oehlenschläger, Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

, August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (, ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than sixty p ...

, Rosemary Sutcliff

Rosemary Sutcliff (14 December 1920 – 23 July 1992) was an English novelist best known for children's books, especially historical fiction and retellings of myths and legends. Although she was primarily a children's author, some of her novel ...

, Esaias Tegnér

Esaias Tegnér (; – ) was a Swedish writer, professor of the Greek language, and bishop. He was during the 19th century regarded as the father of modern poetry in Sweden, mainly through the national romantic epic ''Frithjof's Saga''. He has b ...

, J.R.R. Tolkien, and William T. Vollmann.

See also

*Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been t ...

*'' Beowulf''

References and notes

Sources

Primary:The Skaldic Project, An international project to edit the corpus of medieval Norse-Icelandic skaldic poetry

Other: * Clover, Carol J. et al. ''Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A critical guide'' (University of Toronto Press, 2005) * Gade, Kari Ellen (ed.) ''Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 2 From c. 1035 to c. 1300'' (Brepols Publishers. 2009) * Gordon, E. V. (ed) ''An Introduction to Old Norse'' (Oxford University Press; 2nd ed. 1981) * Jakobsson, Armann; Fredrik Heinemann (trans) ''A Sense of Belonging: Morkinskinna and Icelandic Identity, c. 1220'' (Syddansk Universitetsforlag. 2014) * Jakobsson, Ármann ''Icelandic sagas'' (The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages 2nd Ed. Robert E. Bjork. 2010) * McTurk, Rory (ed) ''A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005) * Ross, Margaret Clunies ''The Cambridge Introduction to the Old Norse-Icelandic Saga'' (Cambridge University Press, 2010) * Thorsson, Örnólfur ''The Sagas of Icelanders'' (Penguin. 2001) * Whaley, Diana (ed.) ''Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 1 From Mythical Times to c. 1035'' (Brepols Publishers. 2012)

Further reading

In Norwegian: * Haugen, Odd Einar ''Handbok i norrøn filologi'' (Bergen:Fagbokforlaget

Fagbokforlaget (literally, 'the textbook press') is a Norwegian publishing company that publishes nonfiction works and teaching aids for instruction at various levels: preschool, primary school, secondary school, adult education, and higher educ ...

, 2004)

External links

*Icelandic Saga Database

– The Icelandic sagas in the original old Norse along with translations into many languages

Old Norse Prose and Poetry

{{Authority control Medieval literature Sources of Norse mythology Icelandic literature North Germanic languages Old Norse literature