SMS Roon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ). was the

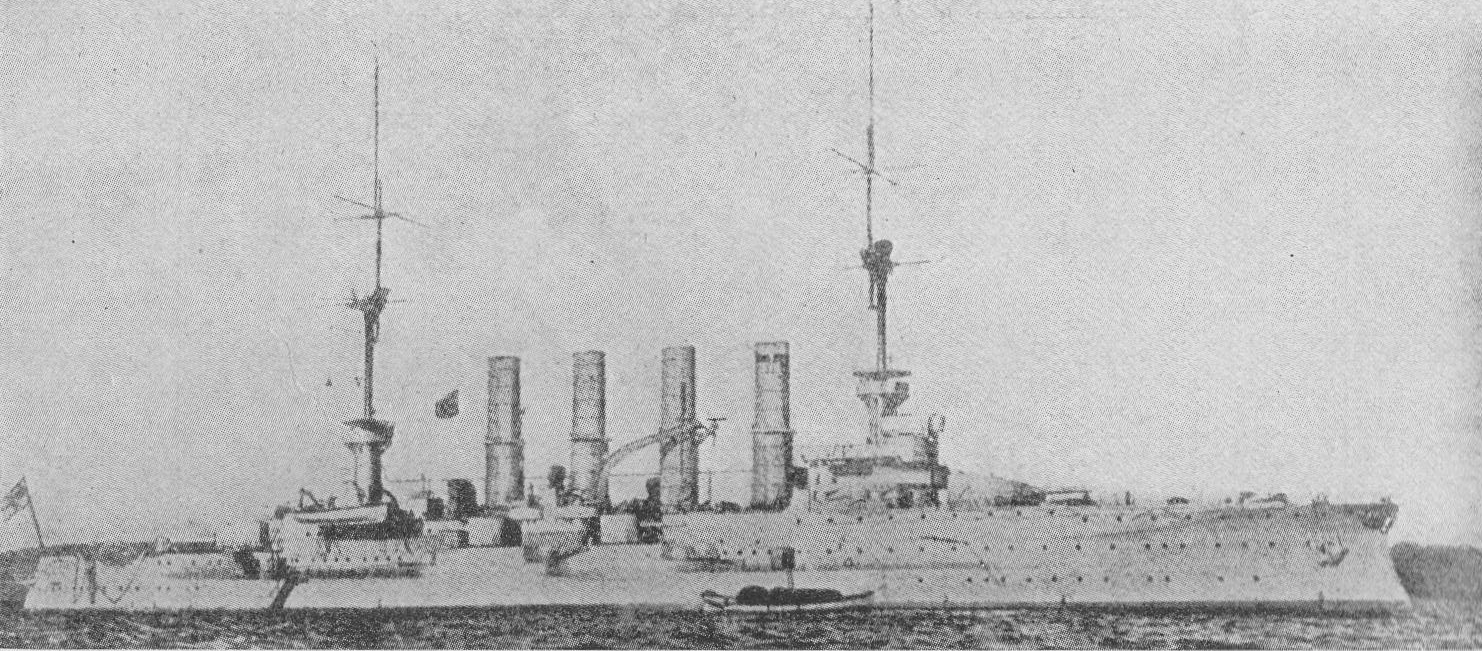

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer

was ordered under the provisional name as a replacement for the

was ordered under the provisional name as a replacement for the  From 11 September to 28 October, briefly resumed her role as deputy flagship; was at that time serving as the group flagship while s sister was being overhauled. Also in October, ''FK''

From 11 September to 28 October, briefly resumed her role as deputy flagship; was at that time serving as the group flagship while s sister was being overhauled. Also in October, ''FK''

The German naval command decided that because and the other armored cruisers of the III Scouting Group were slow and lacked thick enough armor, they were unsuitable for service in the North Sea where they would risk contact with the powerful British Grand Fleet. Therefore, on 15 April 1915, and the rest of III Scouting Group were transferred to the Baltic, where they would face the significantly weaker Russian

The German naval command decided that because and the other armored cruisers of the III Scouting Group were slow and lacked thick enough armor, they were unsuitable for service in the North Sea where they would risk contact with the powerful British Grand Fleet. Therefore, on 15 April 1915, and the rest of III Scouting Group were transferred to the Baltic, where they would face the significantly weaker Russian

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

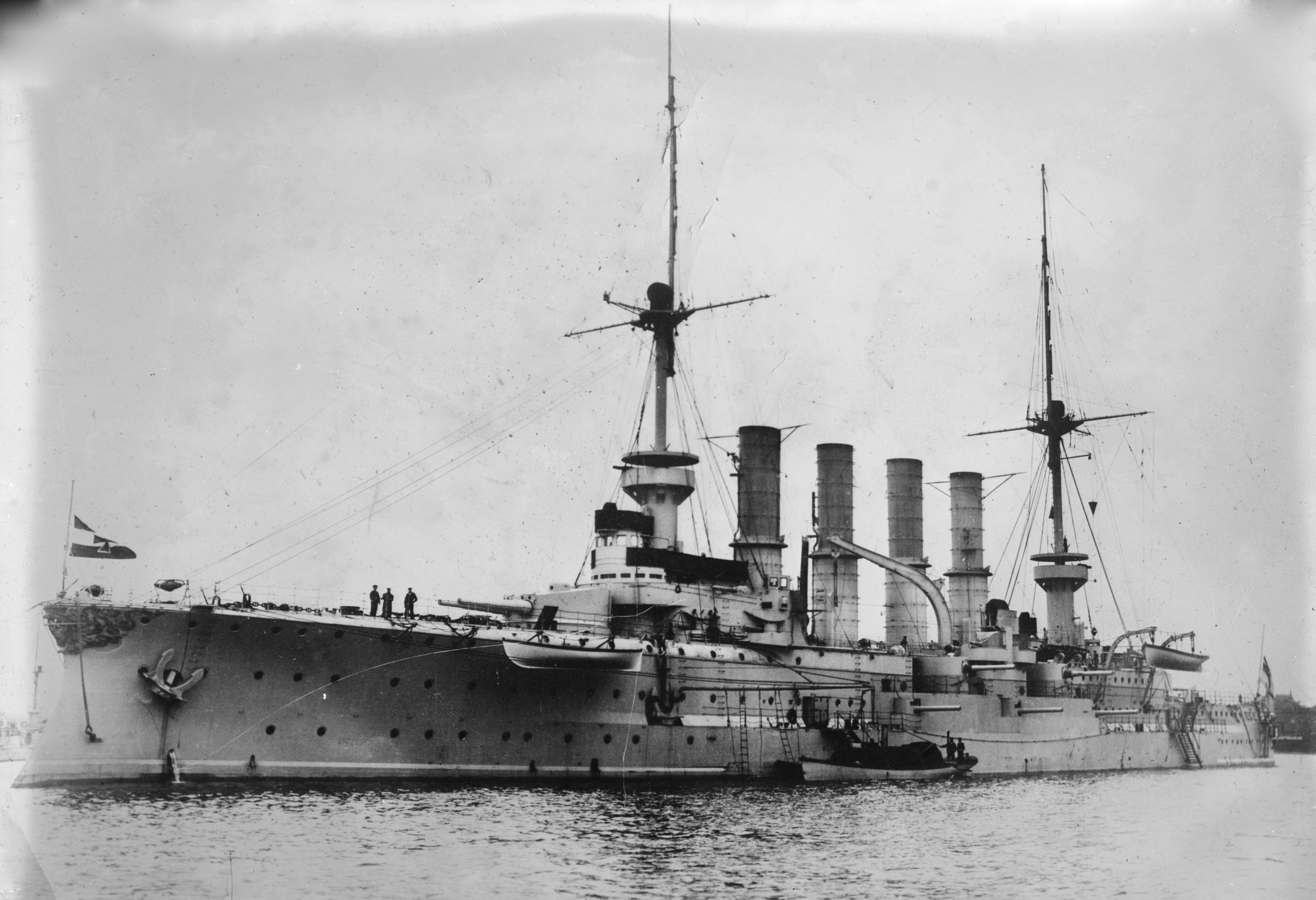

s built for the German (Imperial Navy) in the early 1900s as part of a major naval expansion program aimed at strengthening the fleet. The ship was named after Field Marshal Albrecht von Roon

Albrecht Theodor Emil Graf von Roon (; 30 April 180323 February 1879) was a Prussian soldier and statesman. As Minister of War from 1859 to 1873, Roon, along with Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von Moltke, was a dominating figure in Prussia's ...

. She was built at the in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

, being laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in August 1902, launched in June 1903, and commissioned in April 1906. The ship was armed with a main battery of four guns and had a top speed of . Like many of the late armored cruisers, was quickly rendered obsolescent by the advent of the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

; as a result, her career was limited.

served in I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

, the reconnaissance force of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, for the duration of her peacetime career, including several stints as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the group's deputy commander. During this period, the ship was occupied with training exercises and made several cruises in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1907, she visited the United States to represent Germany during the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

. In September 1911 she was decommissioned and placed in reserve.

Three years later, the ship was mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

in August 1914 following the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and assigned to III Scouting Group, serving initially with the High Seas Fleet in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. There, she escorted the main German fleet during the raid on Yarmouth

The Raid on Yarmouth, on 3 November 1914, was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. German shells only landed on the beach causing little damage to the town, after German ships laying m ...

in November and the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

The Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914 was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, West Hartlepool and Whitby. The bombardments caused hundreds of civilian casualties an ...

in December, though she saw no action during either operation. She was transferred to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

in April 1915 and took part in several operations against Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

forces, including the successful attack on Libau in May and the failed attack on Riga in August. The threat of British submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s convinced the German command to withdraw old vessels like by early 1916, and she was again decommissioned and eventually used as a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

. Plans to convert her into a seaplane tender

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

in 1918 came to nothing with the end of the war, and she was broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of parts, which can be sold for re-use, or for the extraction ...

in 1921.

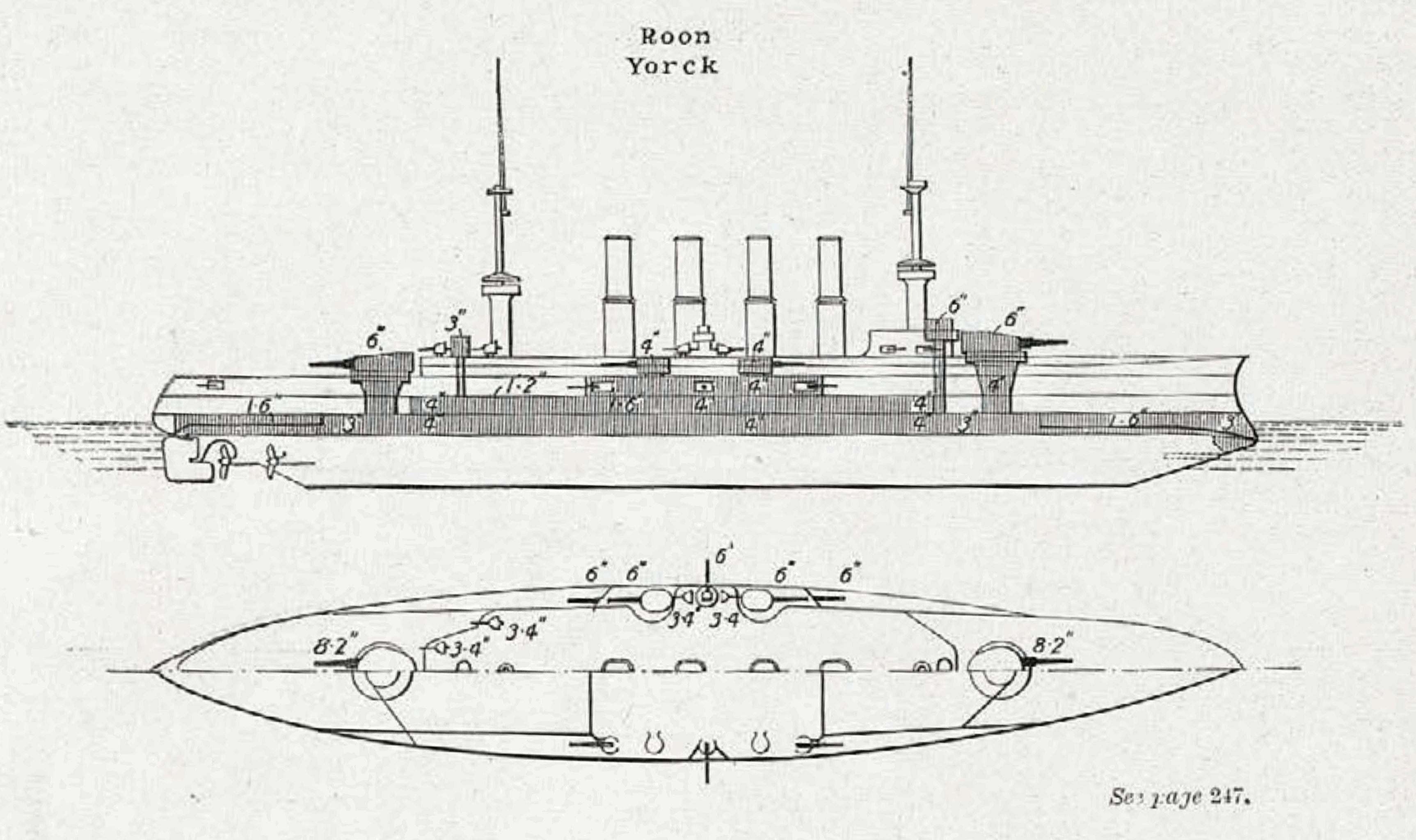

Design

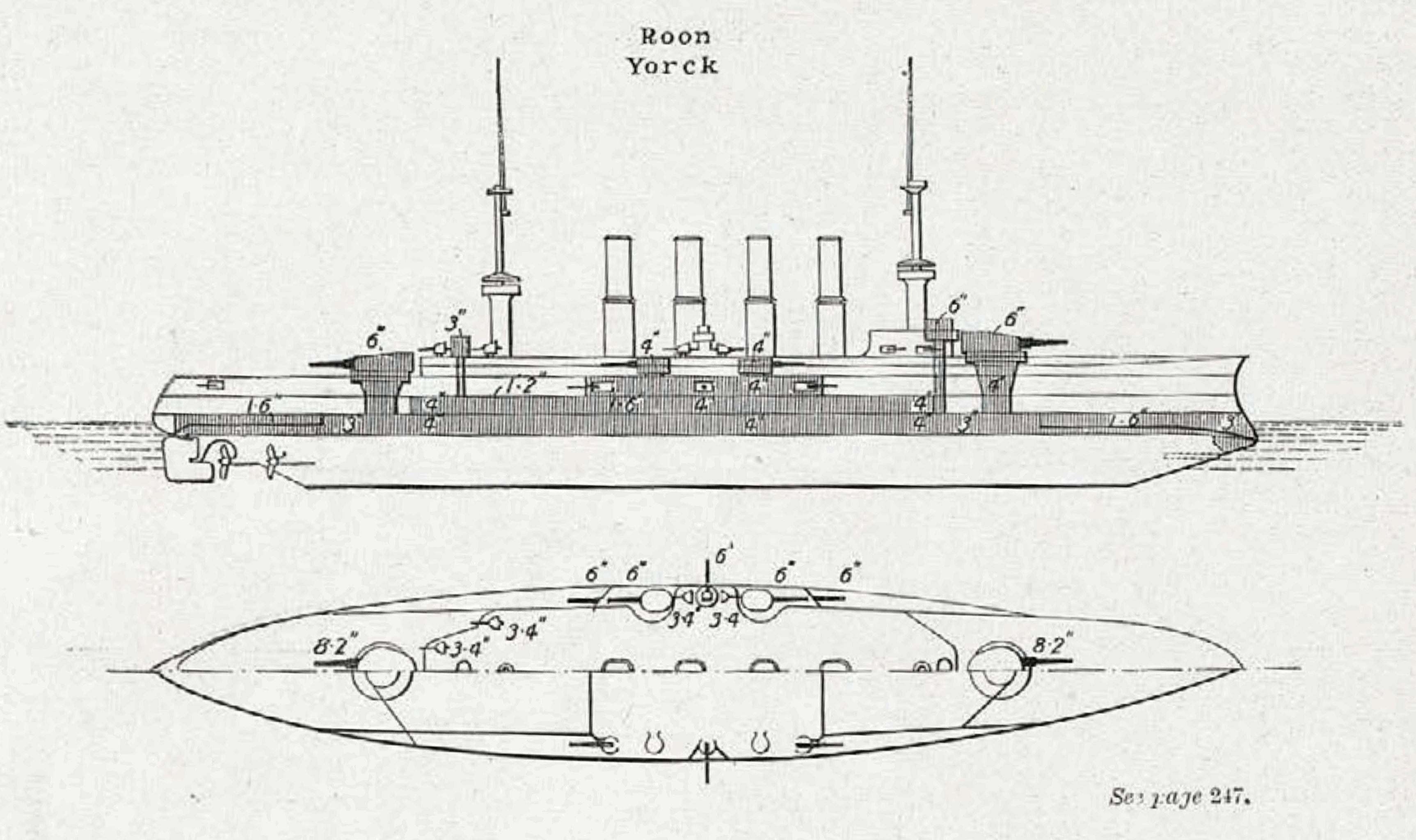

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

; the extra space was used to add a pair of boilers, which increased power by and speed by . The launch of the British battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

in 1907 quickly rendered all of the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s that had been built by the world's navies obsolescent.

was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

of forward. She displaced as built and fully loaded. She was propelled by three vertical triple expansion engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tr ...

s, each driving a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, with steam provided by sixteen coal-fired water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s. The ship's propulsion system developed a total of and yielded a maximum speed of on trials, falling short of her intended speed of . She carried up to of coal, which enabled a maximum range of up to at a cruising speed of . had a crew of 35 officers and 598 enlisted men.

She was armed with four SK L/40 guns arranged in two twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, one on either end of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of ten SK L/40 guns; four were in single-gun turrets on the upper deck and the remaining six were in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

s in a main-deck battery. For close-range defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s, she carried fourteen SK L/35 guns, all in individual mounts in the superstructure and in the hull, either in casemates or open pivot mounts with gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery piece ...

s. She also had four underwater torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one in the bow, one in the stern, and one on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

.

The ship was protected with Krupp cemented armor

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the pr ...

; the belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

was thick amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th t ...

and was reduced to on either end. The main battery turrets had thick faces. Her deck was thick, connected to the lower edge of the belt by thick sloped armor.

Service history

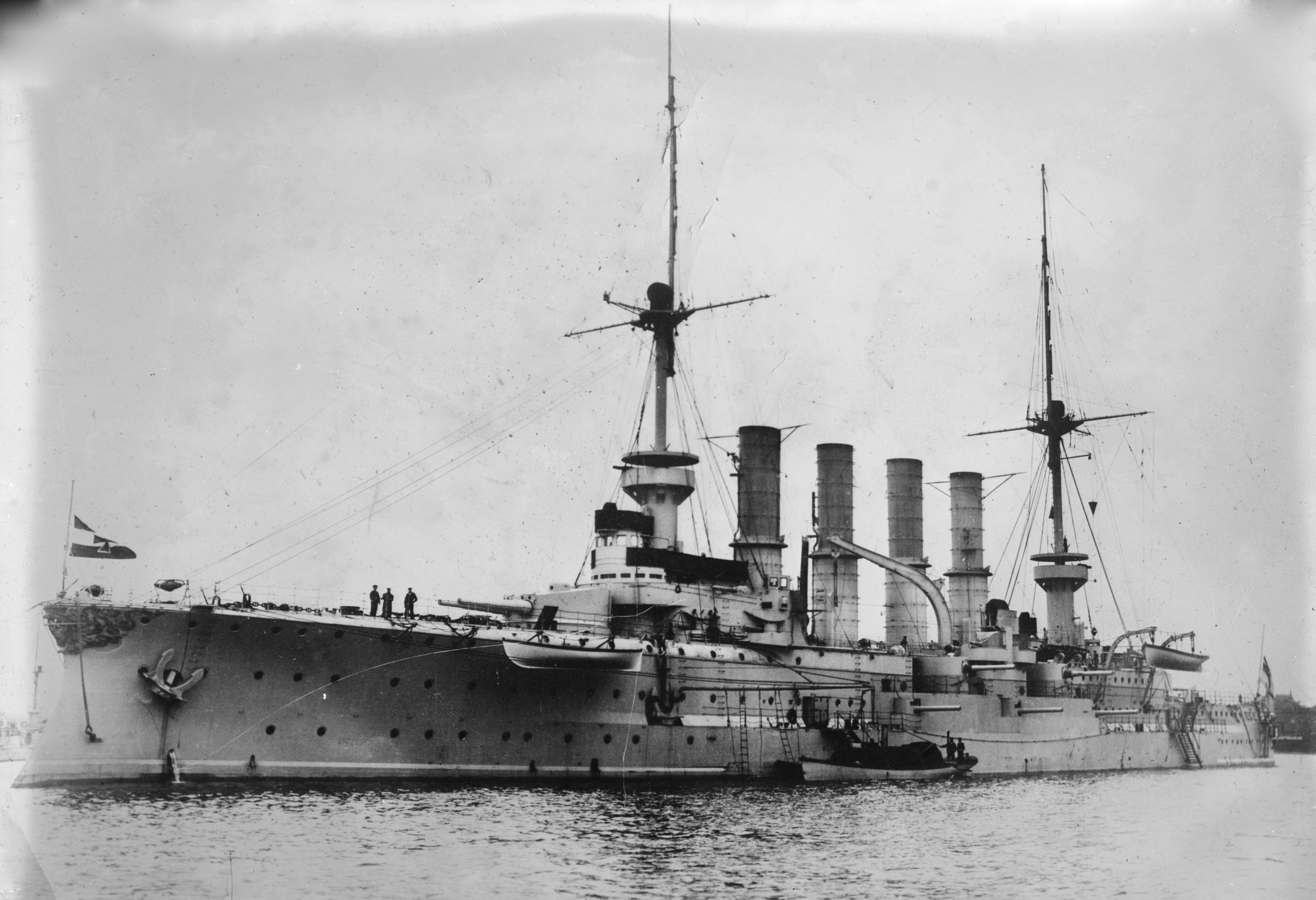

was ordered under the provisional name as a replacement for the

was ordered under the provisional name as a replacement for the ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

. The ship was built at the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

under construction number 28. Her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 1 August 1902 and she was launched on 27 June 1903. At her launching ceremony, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee

Alfred Ludwig Heinrich Karl Graf von Waldersee (8 April 1832 in Potsdam5 March 1904 in Hanover) was a German field marshal (''Generalfeldmarschall'') who became Chief of the Imperial German General Staff.

Born into a prominent military family, ...

christened the ship after Field Marshal Albrecht von Roon

Albrecht Theodor Emil Graf von Roon (; 30 April 180323 February 1879) was a Prussian soldier and statesman. As Minister of War from 1859 to 1873, Roon, along with Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von Moltke, was a dominating figure in Prussia's ...

. Fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work then commenced, which included provisions for the cruiser to be used as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, and was commissioned into the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

fleet on 5 April 1906. Her first commander was (''KzS''—Captain at Sea) Fritz Hoffmann. The ship then began sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s that lasted until 9 July; she joined I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

on 15 August, where she replaced the armored cruiser as the flagship of the deputy commander, ''KzS'' and (Commodore) Raimund Winkler. then participated in the annual fleet maneuvers held in late August and early September. Later that month, Hoffmann was replaced by (''FK''—Frigate Captain) Oskar von Platen-Hallermund, who commanded the vessel for just a month before he was in turn relieved by ''KzS'' Karl Zimmermann. At the same time as Hoffmann's departure, Winkler also left his post, being replaced by ''KzS'' and Eugen Kalau vom Hofe, who transferred his flag to in October.

She spent the following years participating in training exercises and cruises with the ships of I Scouting Group as well as the entire High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. This routine was interrupted in early 1907 when the ship was sent to the United States to participate in the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

, which commemorated the 300th anniversary of the arrival of colonists in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. Kalau von Hofe returned to to lead the German delegation, which also included the light cruiser ; the two cruisers left Kiel on 8 April and crossed the Atlantic to Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, arriving on 24 April. Two days later, the international fleet, which also included contingents from Great Britain, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, France, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, and several other nations, held a naval review as part of the exposition. Following the ceremonies, was detached to remain on station in the Americas while returned to Germany, arriving back in Kiel on 17 May. On her return, Kalau von Hofe shifted back to .

Friedrich Schrader

Friedrich Schrader (19 November 1865 – 28 August 1922) was a German philologist of oriental languages, orientalist, art historian, writer, social democrat, translator and journalist. He also used the pseudonym Ischtiraki (Arabic/ Ottoman fo ...

took command of the ship. The ship went on a major cruise into the Atlantic Ocean from 7 to 28 February 1908 with the other ships of the scouting group. During the cruise, the ships conducted tactical exercises and experimented with using their wireless telegraphy equipment at long distances. They stopped in Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, Spain, to replenish their coal for the voyage home. On 5 March, returned to flagship duty, with now (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Kalau von Hofe back aboard the ship.

Another Atlantic cruise followed in July and August; this time, the cruise was made in company with the battleship squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. Prince Heinrich, the fleet commander, had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that ...

were high. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

to the North Sea, and continued to the Atlantic. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August. The autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September. On 23 September, ''KAdm'' Jacobsen replaced Kalau von Hofe, and the following month ''FK'' Georg Scheidt took command of .

The year 1909 saw two more cruises in the Atlantic, the first in February with just the ships of I Scouting Group and the second in July and August with the rest of the fleet. On the way back to Germany, the fleet stopped in Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

, Britain, where it was received by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. ''KzS'' Reinhard Koch Reinhard is a German, Austrian, Danish, and to a lesser extent Norwegian surname (from Germanic ''ragin'', counsel, and ''hart'', strong), and a spelling variant of Reinhardt.

Persons with the given name

* Reinhard of Blankenburg (after 1107 – 1 ...

relieved Jacobsen as the group deputy commander after the annual fleet maneuvers in September 1909 but on 1 October he transferred his flag to . The next two years passed uneventfully for ; apart from the typical training routine, she took part in a naval review for Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and List of monarchs of Prussia, King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication on 9 ...

in September 1911, after which she was decommissioned on 22 September.

World War I

Following the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in July 1914, was mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

for wartime service on 2 August and was initially assigned to II Scouting Group

II is the Roman numeral for 2.

II may also refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Image intensifier, medical imaging equipment

*Invariant chain, a polypeptide involved in the formation and transport of MHC class II protein

*Optic nerve, the second ...

as the flagship of ''KAdm'' Gisberth Jasper. The ship's first wartime commander was ''KzS'' Johannes von Karpf

Johannes is a Medieval Latin form of the personal name that usually appears as " John" in English language contexts. It is a variant of the Greek and Classical Latin variants (Ιωάννης, '' Ioannes''), itself derived from the Hebrew name '' Y ...

. A series of reorganizations saw the ship transferred to IV Scouting Group to replace the armored cruiser and on 25 August IV Scouting Group was renamed III Scouting Group, remaining as flagship. ''KAdm'' Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz

''Vizeadmiral'' Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz (14 August 1863 Frankfurt (Oder) – 16 February 1933 (Dresden)) was a German admiral. In 1899 he served as the German Naval attaché to Washington and later in 1912 commanded a flotilla of German vesse ...

replaced Jasper as the group commander. The following day, and the rest of the group took part in a sortie into the eastern Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

in a failed attempt to rescue the light cruiser that had run aground in Russian territory. The operation was cancelled on 27 August when Rebeur-Paschwitz received word that had been scuttled to avoid capture by Russian forces.

The group was stationed in the North Sea from 6 September to guard the German coast, interrupted by a short deployment to the Danish straits from 25 to 26 September after false reports of British warships attempting to pass through prompted the German command to send the cruisers on a patrol there. During their period in the North Sea, the cruisers were sent to escort the minelaying

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing controll ...

cruisers and and the auxiliary minelayer as they laid the "Alpha" defensive minefield in the North Sea. The ships then escorted the main body of the High Seas Fleet during the raid on Yarmouth

The Raid on Yarmouth, on 3 November 1914, was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. German shells only landed on the beach causing little damage to the town, after German ships laying m ...

on 2–3 November.

A month later, on 15–16 December, she participated in the bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby. Along with the armored cruiser , was assigned to the van

A van is a type of road vehicle used for transporting goods or people. Depending on the type of van, it can be bigger or smaller than a pickup truck and SUV, and bigger than a common car. There is some varying in the scope of the word across th ...

of the High Seas Fleet, which was providing distant cover to Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

's battlecruisers while they were conducting the bombardment. During the operation, and her attached destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s encountered the British screening forces; came in contact with the destroyers and , but no gunfire was exchanged and the ships turned away. Following reports of British destroyers from as well as from , Admiral von Ingenohl ordered the High Seas Fleet to disengage and head for Germany. At this point, and her destroyers became the rearguard for the High Seas Fleet. , by this time joined by the light cruisers and , encountered Commander Loftus Jones

Commander Loftus William Jones VC (13 November 1879 – 31 May 1916) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth fo ...

' destroyers. Jones shadowed for about 45 minutes, at which point and were detached to sink their pursuers. Twenty minutes later, signaled the two light cruisers and ordered them to abandon the pursuit and retreat along with the rest of the High Seas Fleet. In the meantime, Vice Admiral David Beatty received word of s location, and in an attempt to intercept the German cruisers, detached the battlecruiser to hunt the German ships down, while his other three battlecruisers followed from a distance. While still pursuing the retreating Germans, Beatty had become aware that the German battlecruisers were shelling Hartlepool, so he decided to break off the pursuit of and turn towards the German battlecruisers.

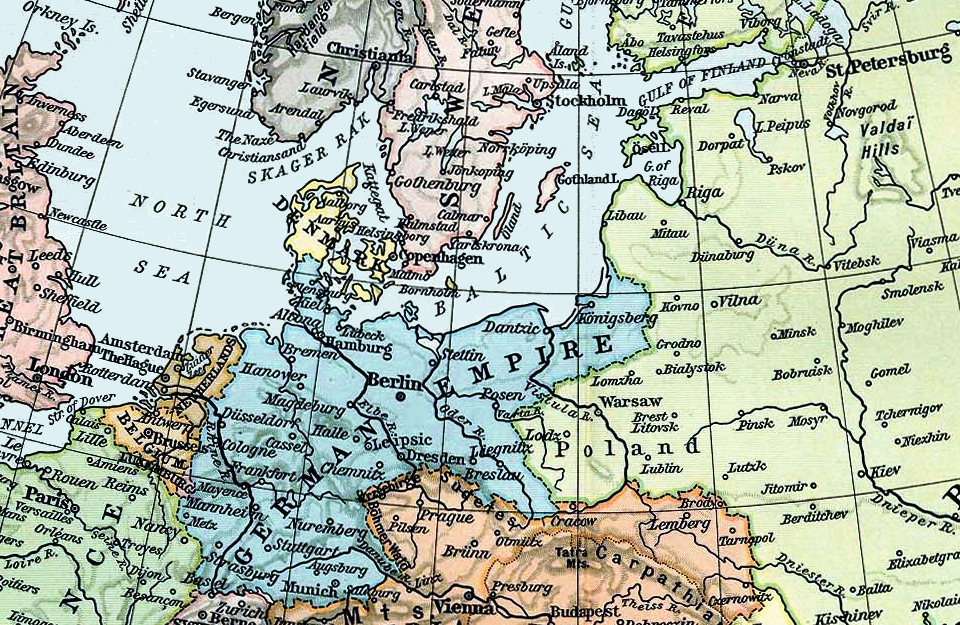

Operations in the Baltic

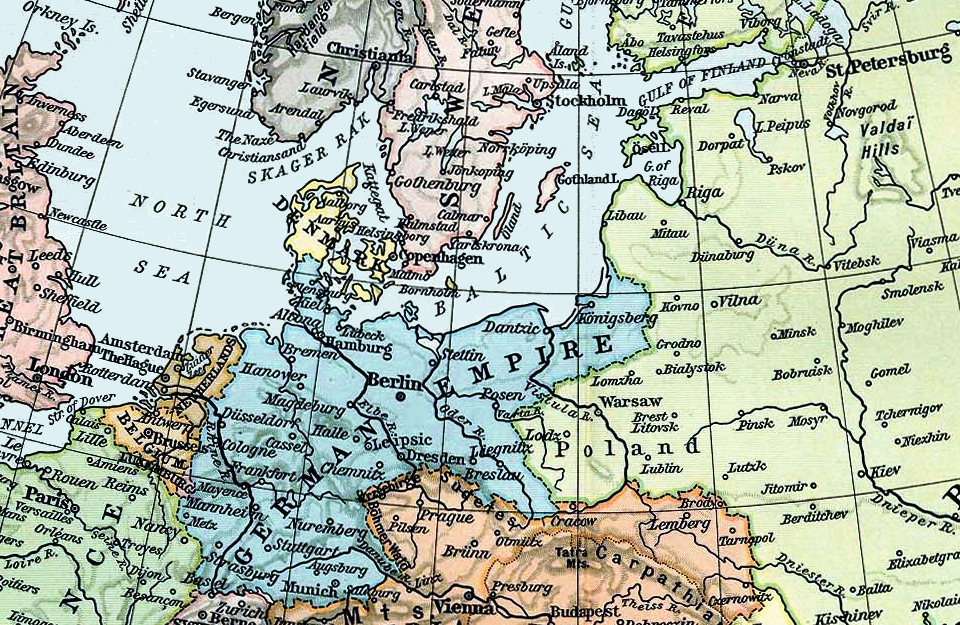

The German naval command decided that because and the other armored cruisers of the III Scouting Group were slow and lacked thick enough armor, they were unsuitable for service in the North Sea where they would risk contact with the powerful British Grand Fleet. Therefore, on 15 April 1915, and the rest of III Scouting Group were transferred to the Baltic, where they would face the significantly weaker Russian

The German naval command decided that because and the other armored cruisers of the III Scouting Group were slow and lacked thick enough armor, they were unsuitable for service in the North Sea where they would risk contact with the powerful British Grand Fleet. Therefore, on 15 April 1915, and the rest of III Scouting Group were transferred to the Baltic, where they would face the significantly weaker Russian Baltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

. The unit was dissolved and and the other vessels were assigned to the Reconnaissance Forces of the Baltic, under the command of ''KAdm'' Albert Hopman

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert C ...

. At the same time, ''FK'' Hans Gygas replaced Karpf, who in turn became the deputy commander of the unit and made his flagship. On 30 April, the ship went into drydock in Kiel for an overhaul, returning to service for the attack on Libau on 7 May. On 11 May, the British submarine spotted and several other ships en route to Libau, which had been recently captured by the German army. ''E9'' fired five torpedoes at the German flotilla, all of which missed; two passed closely astern of . thereafter took part in a series of sorties into the central Baltic as far north as Gotska Sandön

Gotska Sandön (literally translated as "The Gotlandic Sand Island") is an uninhabited Swedish island north of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. It has been a national park since 1909.

Geography

Gotska Sandön is situated north of Fårö in the Balt ...

on 13–16 May, 23–26 May, 2–6 June, 11–13 June, and 20–22 June.

Karpf transferred to the light cruiser while Hopman relocated to since the latter's flagship, the armored cruiser , was under repairs for a torpedo hit. and covered a minelaying operation with on 30 June that lasted through 2 July and resulted in the Battle of Åland Islands

The Battle of Åland Islands, or the Battle of Gotland, which occurred in July 1915, was a naval battle of World War I between the German Empire and the Russian Empire, assisted by a submarine of the British Baltic Flotilla. It took place i ...

. The light cruiser and three destroyers were escorting when they were attacked by the armored cruisers , , and the light cruisers and . escaped while the destroyers covered the retreat of , which was severely damaged and forced to seek refuge in neutral Swedish waters. joined to relieve the beleaguered German destroyers. Upon arriving at the scene, engaged , and opened fire on . Shortly thereafter, the Russian cruiser , along with a destroyer, arrived to reinforce the Russian flotilla. In the following artillery duel, was hit several times, and the German ships were forced to retreat.

Later in July, as the German Army began to push further north from Libau, the naval command reinforced the naval forces in the Baltic to support the advance. The pre-dreadnought battleships of the IV Battle Squadron were transferred to the eastern Baltic and its commander, (Vice Admiral) Ehrhard Schmidt

Ehrhard Schmidt (18 May 1863 – 18 July 1946) was an admiral of the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial German Navy) during World War I.

Career

At age 15 he entered the navy and saw service at several branches at sea and on land. Among them were ...

, was placed in command of the naval forces in the area. In August, the German fleet attempted to clear the Gulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia ( lv, Rīgas līcis, et, Liivi laht) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main con ...

of Russian naval forces to aid the German Army advancing on the city. Elements of the High Seas Fleet were sent to strengthen the forces attempting to break into the gulf. The Germans made several attempts to force their way into the gulf during the Battle of the Gulf of Riga until reports of British submarines in the area prompted the Germans to call off the operation on 20 August. During these attacks, remained outside the gulf and on 10 August, and shelled Russian positions at Zerel on the Sworbe Peninsula. There were several Russian destroyers anchored off Zerel; the German cruisers caught them by surprise and damaged one of them.

On 9 September, Hopman returned to , allowing to return to Kiel for an overhaul. Work was completed by mid-October and the ship returned to Libau on 18 October. Two days later, Hopman made her his flagship once again. The loss of three days later to a British submarine convinced the German command that the threat of underwater weapons was too serious to continue to operate older vessels with insufficient protection, including . Accordingly, on 15 January 1916, Hopman hauled down his flag, and two days later the ship left Libau to return to Kiel, where she was decommissioned on 4 February.

Fate

In November 1916, was disarmed and converted into a training and accommodation ship. Stationed at Kiel, she served in this capacity until 1918. The German Navy had previously experimented with seaplane carriers, including the conversion of the old light cruiser early in 1918 for service with the fleet. could carry only two aircraft, which was deemed insufficient for fleet support. As a result, plans were drawn up to convert into a seaplane carrier, with a capacity for four aircraft. The ship's main battery would have been removed and replaced with six 15 cm guns and six 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns; the large hangar for the seaplanes was to have been installed aft of the main superstructure. The plan did not come to fruition, primarily because the German Navy relied onzeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s for aerial reconnaissance, not seaplanes. was struck from the naval register

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval author ...

on 25 November 1920 and scrapped

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

the following year in Kiel-Nordmole.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Roon Roon-class cruisers Ships built in Kiel 1903 ships World War I cruisers of Germany