SMS Brandenburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was the lead ship of the pre-dreadnought

was the first pre-dreadnought battleship of the (Imperial Navy). Prior to the ascension of

was the first pre-dreadnought battleship of the (Imperial Navy). Prior to the ascension of

Ordered as battleship ''A'', was

Ordered as battleship ''A'', was  Repair work was completed by 16 April, allowing to return to trials which lasted until the middle of August, and included a cruise through the Kattegat. On 21 August, the ship joined II Division, though a reorganization of the fleet saw the ship transferred to I Division, along with her three

Repair work was completed by 16 April, allowing to return to trials which lasted until the middle of August, and included a cruise through the Kattegat. On 21 August, the ship joined II Division, though a reorganization of the fleet saw the ship transferred to I Division, along with her three

At the outbreak of

At the outbreak of

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s, which included , , and , built for the German (Imperial Navy) in the early 1890s. She was the first pre-dreadnought built for the German Navy; earlier, the navy had only built coastal defense ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of Littoral (military), coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized ...

s and armored frigates. The ship was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

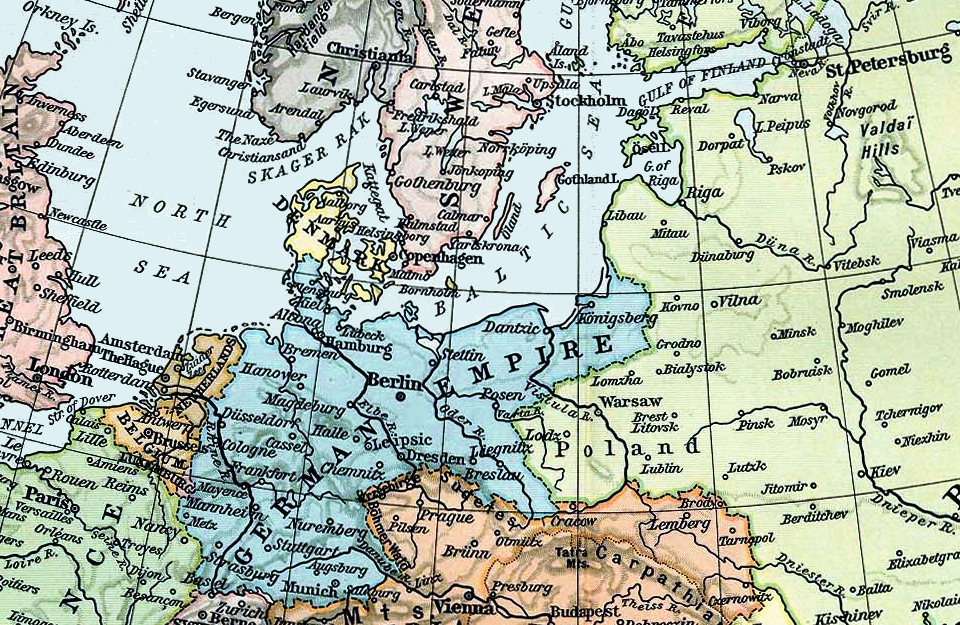

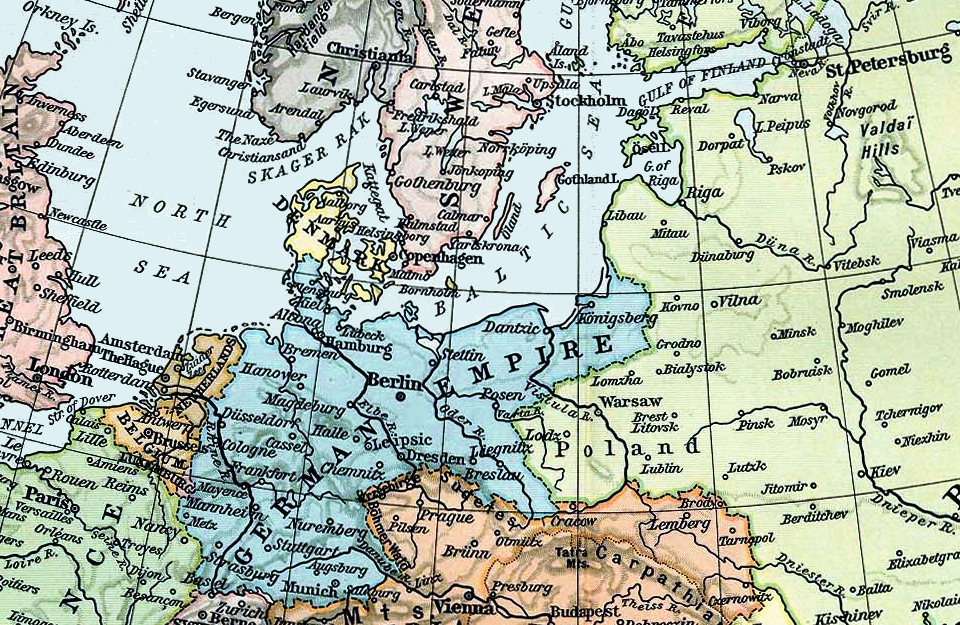

at the AG Vulcan dockyard in 1890, launched on 21 September 1891, and commissioned into the German Navy on 19 November 1893. and her three sisters were unique for their time in that they carried six heavy guns instead of the four that were standard in other navies. She was named after the Province of Brandenburg

The Province of Brandenburg (german: Provinz Brandenburg) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1945. Brandenburg was established in 1815 from the Kingdom of Prussia's core territory, comprised the bulk of the historic Margraviate of Brandenburg ...

.

served with I Division during the first decade of her service with the fleet. This period was generally limited to training exercises and goodwill visits to foreign ports. These training maneuvers were nevertheless very important to developing German naval tactical doctrine in the two decades before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, especially under the direction of Alfred von Tirpitz. The ship saw her first major deployment in 1900, when she and her three sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s were deployed to China to suppress the Boxer Uprising

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

. In the early 1900s, all four ships were heavily rebuilt. She was obsolete by the start of World War I and only served in a limited capacity, initially as a coastal defense ship. In December 1915, she was withdrawn from active service and converted into a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

. was scrapped in Danzig, after the war, in 1920.

Design

was the first pre-dreadnought battleship of the (Imperial Navy). Prior to the ascension of

was the first pre-dreadnought battleship of the (Imperial Navy). Prior to the ascension of Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

to the German throne in June 1888, the German fleet had been largely oriented toward defense of the German coastline and Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprara de Montecuccoli (English: ''Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprara, and Montecuccoli''; born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman who served as the cha ...

, chief of the (Imperial Naval Office), had ordered a number of coastal defense ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of Littoral (military), coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized ...

s in the 1880s. In August 1888, the Kaiser, who had a strong interest in naval matters, replaced Caprivi with (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Alexander von Monts

Alexander Graf von Monts de Mazin (born 9 August 1832 in Berlin; died 19 January 1889) was an officer in the Prussian Navy and later the German Imperial Navy. He saw action during the Second Schleswig War at the Battle of Jasmund on 17 March 18 ...

and instructed him to include four battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s in the 1889–1890 naval budget. Monts, who favored a fleet of battleships over the coastal defense strategy emphasized by his predecessor, cancelled the last four coastal defense ships authorized under Caprivi and instead ordered four battleships. Though they were the first modern battleships built in Germany, presaging the Tirpitz Tirpitz may refer to:

* Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930), German admiral

* German battleship ''Tirpitz'', a World War II-era Bismarck-class battleship named after the admiral

* Tirpitz (pig), a pig rescued from the sinking of SMS ''Dresden'' and ...

-era High Seas Fleet, the authorization for the ships came as part of a construction program that reflected the strategic and tactical confusion of the 1880s caused by the (Young School).

and her sister ships—, , and —were long, with a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft of . She displaced as designed and up to at full combat load. She was equipped with two sets of 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion steam engines that each drove a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

. Steam was provided by twelve transverse cylindrical Scotch marine boilers. The ship's propulsion system was rated at and a top speed of . She had a maximum range of at a cruising speed of . Her crew numbered 38 officers and 530 enlisted men.

The ship was unusual for its time in that it possessed a broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

of six heavy guns in three twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, rather than the four-gun main battery typical of contemporary battleships. The forward and after turrets carried 28 cm (11 in) K L/40 guns, while the amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th t ...

turret mounted a pair of 28 cm (11 in) guns with shorter L/35 barrels. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of eight SK L/35 quick-firing guns mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

s and eight 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns, also casemate mounted. s armament system was rounded out with six torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, all in above-water swivel mounts. Although the main battery was heavier than other capital ships of the period, the secondary armament was considered weak in comparison to other battleships.

The ship was protected with compound armor

Compound armour was a type of armour used on warships in the 1880s, developed in response to the emergence of armor-piercing shells and the continual need for reliable protection with the increasing size in naval ordnance. Compound armour was a no ...

. Her main belt armor was thick in the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

that protected the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces. The deck was thick. The main battery barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s were protected with thick armor.

Service history

Construction to 1896

Ordered as battleship ''A'', was

Ordered as battleship ''A'', was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at AG Vulcan in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

in May 1890. Her hull was completed by September 1891 and launched on 21 September, when she was christened by Wilhelm II. Fitting out work followed and was finished, with the exception of the installation of her guns, by the end of September 1893, when she was transferred to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

. There, her guns were mounted, and on 19 November was commissioned into the fleet. Sea trials began four days later; on the first day of trials, Wilhelm II and a delegation from the Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

provincial government came aboard the ship to observe. On 27 December, the ship received a flag bearing the coat of arms of Brandenburg

This article is about the coat of arms of the German state of Brandenburg.

History

According to tradition, the ''Märkischer Adler'' ('Marcher eagle'), or red eagle of the March of Brandenburg, was adopted by Margrave Gero in the 10th centu ...

, which was flown on special occasions. At the end of the month, was formally assigned to II Division of the Maneuver Squadron.

Trials continued into 1894, and while conducting forced draft tests in Strander Bucht on 16 February, the ship suffered the worst machinery accident in the history of the . One of the main steam valves from the starboard boilers exploded, killing forty-four men in the boiler room and injuring another seven. The cause of the explosion was a defect in the construction of the valve. Prince Henry Prince Henry (or Prince Harry) may refer to:

People

*Henry the Young King (1155–1183), son of Henry II of England, who was crowned king but predeceased his father

*Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394–1460)

*Henry, Duke of Cornwall (Ja ...

, aboard the nearby transport ship , immediately ordered the ship to come to s aid, and took off the dead and wounded men. then put into Wiker Bucht, and was later towed to Kiel, where she entered the (Imperial Shipyard) for repairs. The accident caused a minor political incident after the press criticized Wilhelm II for failing to send Prince Henry to the funerals for the sailors. Additionally, ''VAdm'' Friedrich von Hollmann

Friedrich von Hollmann (19 January 1842 – 21 January 1913) was an Admiral of the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) and Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office under Emperor Wilhelm II.

Naval career

Hollmann was born in Berlin ...

, the State Secretary of the (Imperial Naval Office) stated before the (Imperial Diet) that "such accidents could occur again and again", which increased parliamentary resistance to further increases in naval budgets; this led to an initial rejection of funds for the first armored cruiser, . Admirals Eduard von Knorr

Ernst Wilhelm Eduard von Knorr (8 March 1840 – 17 February 1920) was a German admiral of the Kaiserliche Marine who helped establish the German colonial empire.

Life

Born in Saarlouis, Rhenish Prussia, Knorr entered the Prussian Navy i ...

and Hans von Koester

Hans Ludwig Raimund von Koester (29 April 1844 – 21 February 1928) was a German naval officer who served in the Prussian Navy and later in the Imperial German Navy. He retired as a Grand Admiral.

Career overview

Born Hans Ludwig Raimund Koeste ...

criticized the comment, forcing Hollmann to publicly apologize.

Repair work was completed by 16 April, allowing to return to trials which lasted until the middle of August, and included a cruise through the Kattegat. On 21 August, the ship joined II Division, though a reorganization of the fleet saw the ship transferred to I Division, along with her three

Repair work was completed by 16 April, allowing to return to trials which lasted until the middle of August, and included a cruise through the Kattegat. On 21 August, the ship joined II Division, though a reorganization of the fleet saw the ship transferred to I Division, along with her three sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s. I Division was based in Wilhelmshaven in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. and the rest of the squadron attended ceremonies for the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

at Kiel on 3 December. The squadron thereafter began a winter training cruise in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

; this was the first such cruise by the German fleet. In previous years, the bulk of the fleet was deactivated for the winter months. During this voyage, I Division anchored in Stockholm from 7 to 11 December, during the 300th anniversary of the birth of Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

. King Oscar II held a reception for the visiting German delegation. Thereafter, further exercises were conducted in the Baltic before the ships had to put into their home ports for repairs.

The year 1895 began with what became the normal training cruises to Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

and then to Bremerhaven, with Wilhelm II onboard the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, . This was followed by individual ship and divisional training, which was interrupted by a voyage to the northern North Sea, the first time that units of the main German fleet had left home waters. On this trip, joined and the two battleships stopped in Lerwick

Lerwick (; non, Leirvik; nrn, Larvik) is the main town and port of the Shetland archipelago, Scotland. Shetland's only burgh, Lerwick had a population of about 7,000 residents in 2010.

Centred off the north coast of the Scottish mainland ...

in Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

from 16 to 23 March. These exercises tested the ships in heavy weather; both vessels performed admirably. In May, more fleet maneuvers were carried out in the western Baltic, and they were concluded by a visit of the fleet to Kirkwall in Orkney. The squadron returned to Kiel in early June, where preparations were underway for the opening of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. Tactical exercises were carried out in Kiel Bay

The Bay of Kiel or Kiel Bay (, ; ) is a bay in the southwestern Baltic Sea, off the shores of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany and the islands of Denmark. It is connected with the Bay of Mecklenburg in the east, the Little Belt in the northwest, ...

in the presence of foreign delegations to the opening ceremony. Further training exercises lasted until 1 July, when I Division began a voyage into the Atlantic Ocean. This operation had political motives; Germany had only been able to send a small contingent of vessels—the protected cruiser , the coastal defense ship , and the sailing frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

—to an international naval demonstration off the Moroccan coast at the same time. The main fleet could therefore provide moral support to the demonstration by steaming to Spanish waters. Rough weather again allowed and her sister ships to demonstrate their excellent seakeeping. The fleet departed Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Penins ...

and stopped in Queenstown, Ireland. Wilhelm II, aboard his yacht , attended the Cowes Regatta while the rest of the fleet stayed off the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

.

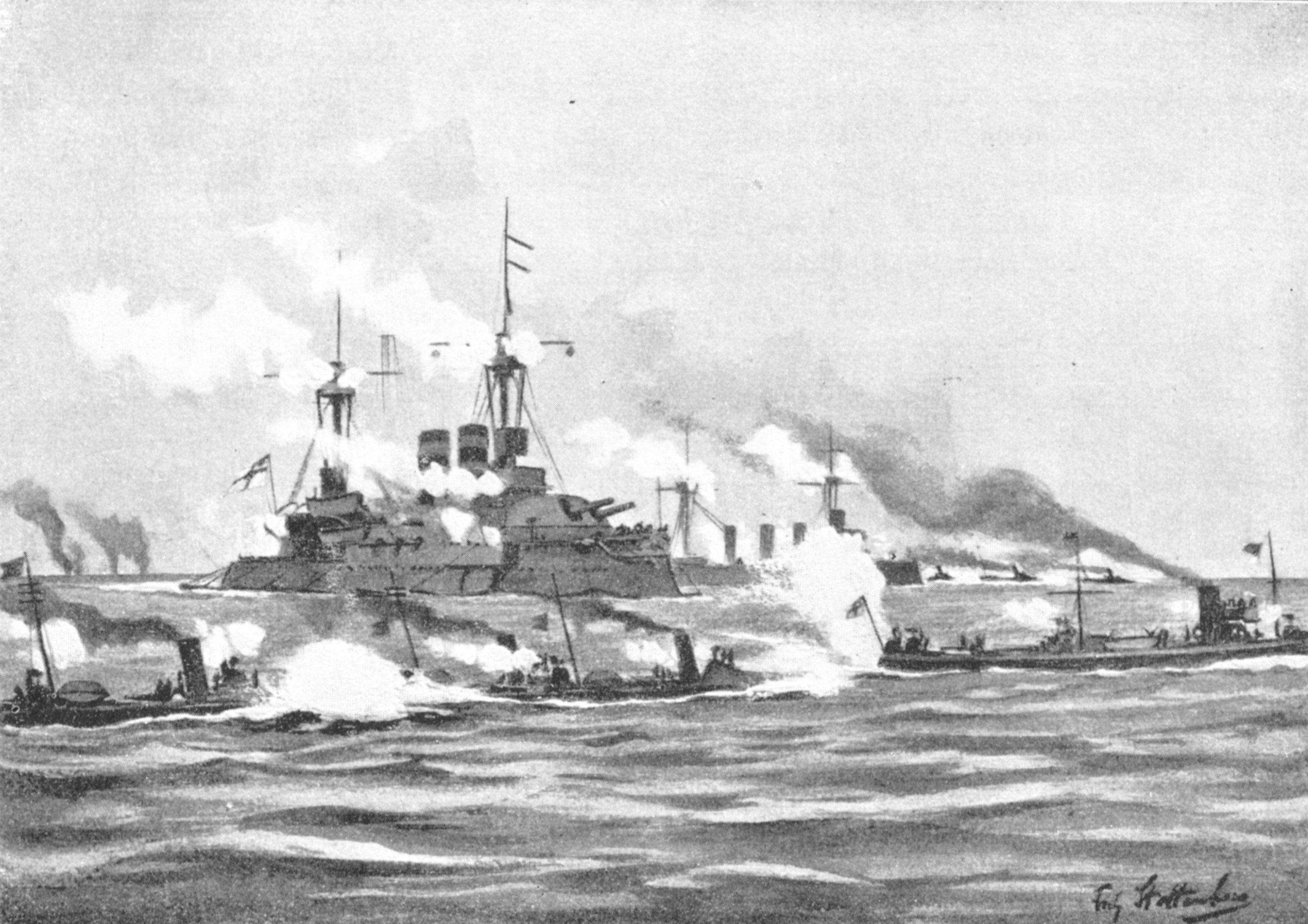

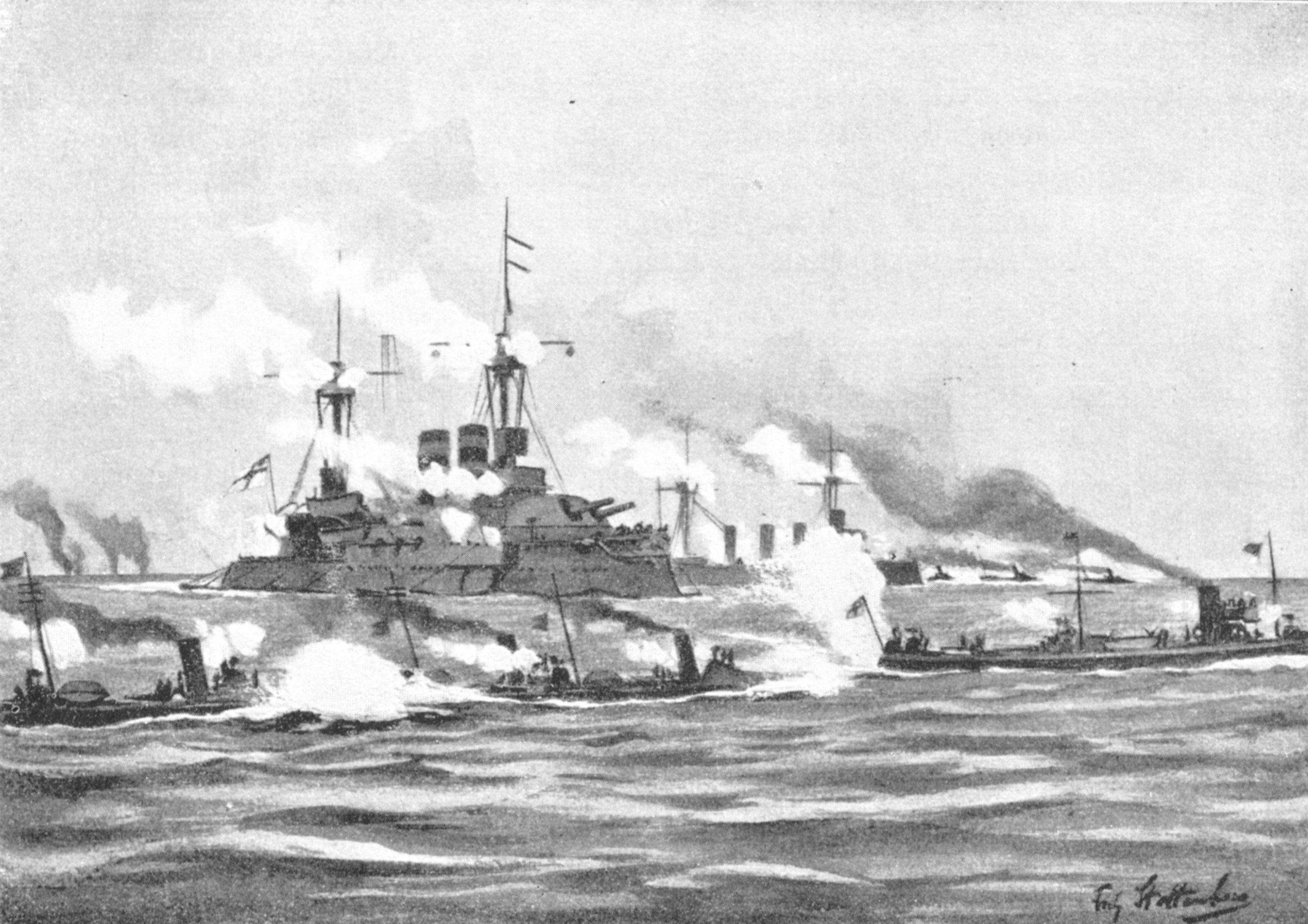

On 10 August, the fleet returned to Wilhelmshaven and began preparations for the autumn maneuvers later that month. The first exercises began in the Heligoland Bight on 25 August. The fleet then steamed through the Skagerrak to the Baltic; heavy storms caused significant damage to many of the ships and the torpedo boat capsized and sank in the storms—only three men were saved. The fleet stayed briefly in Kiel before resuming exercises, including live-fire exercises, in the Kattegat and the Great Belt. During this period, on 22 August, collided with the aviso , though only the latter was damaged in the accident. The main maneuvers began on 7 September with a mock attack from Kiel toward the eastern Baltic. The next day, while she was in Kiel, Czar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

of Russia inspected during a visit to Germany. Subsequent maneuvers took place off the coast of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and in Danzig Bay. A fleet review for Wilhelm II off Jershöft concluded the maneuvers on 14 September. The rest of the year was spent on individual ship training. The year 1896 followed much the same pattern as the previous year. Individual ship training was conducted through April, followed by squadron training in the North Sea in late April and early May, which included a visit to the Dutch ports of Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic l ...

and Nieuwediep. Further maneuvers, which lasted from the end of May to the end of July, took the squadron further north in the North Sea, frequently into Norwegian waters where the ships visited Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

from 11 to 18 May. During the maneuvers, Wilhelm II and the Chinese viceroy Li Hongzhang observed a fleet review off Kiel. On 9 August, the training fleet assembled in Wilhelmshaven for the annual autumn fleet training.

1897–1900

and the rest of the fleet operated under the normal routine of individual and unit training in the first half of 1897. Early in the year, the naval command considered deploying I Division to another naval demonstration off Morocco to protest the murder of two German nationals there, but a smaller squadron of sailing frigates was sent instead. The typical routine was interrupted in early August when Wilhelm II and (Empress) Augusta went to visit the Russian imperial court; both divisions of I Squadron were sent to Kronstadt to accompany the Kaiser, who proceeded to the capital atSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. They had returned to Neufahrwasser

Nowy Port (german: Neufahrwasser; csb, Fôrwôter) is a district of the city of Gdańsk, Poland. It borders with Brzeźno to the west, Letnica to the south, and Przeróbka to the east (over the Martwa Wisła).

The landmark of the district is ...

in Danzig on 15 August, where the rest of the fleet joined them for the annual autumn maneuvers. These exercises reflected the tactical thinking of the new State Secretary of the , (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz, and the new commander of I Squadron, ''VAdm'' August von Thomsen. These new tactics stressed accurate gunnery, especially at longer ranges, though the necessities of the line-ahead formation led to a great deal of rigidity in the tactics. Thomsen's emphasis on shooting created the basis for the excellent German gunnery during World War I. The maneuvers were completed by 22 September in Wilhelmshaven.

In early December, I Division conducted maneuvers in the Kattegat and the Skagerrak, though they were cut short due to shortages in officers and men. Additionally, while steaming through the Great Belt, collided with the ironclad , damaging both vessels and forcing them to put into Kiel for repairs. After temporary repairs to were completed, she moved to Wilhelmshaven, where a new ram bow had to be installed. The fleet followed the typical routine of individual and fleet training in 1898 without incident, though a voyage to the British Isles was also included and the fleet stopped in Queenstown, Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, and Kirkwall. The fleet assembled in Kiel on 14 August for the annual autumn exercises: the maneuvers included a mock blockade of the coast of Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label=Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwerin ...

and a pitched battle with an "Eastern Fleet" in the Danzig Bay. While steaming back to Kiel, a severe storm hit the fleet, causing significant damage to many ships and sinking the torpedo boat . The fleet then transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and continued the maneuvers in the North Sea. Training finished on 17 September in Wilhelmshaven. In December, I Division conducted artillery and torpedo training in Eckernförde Bay

Eckernförde Bay (german: Eckernförder Bucht; da, Egernførde Fjord or Egernfjord) is a firth and a branch of the Bay of Kiel between the Danish Wahld peninsula in the south and the Schwansen peninsula in the north in the Baltic Sea off the lan ...

, followed by divisional training in the Kattegat and Skagerrak. During these maneuvers, the division visited Kungsbacka

Kungsbacka () (old da, Kongsbakke) is a locality and the seat of Kungsbacka Municipality in Halland County, Sweden, with 19,057 inhabitants in 2010.

It is one of the most affluent parts of Sweden, in part due to its simultaneous proximity to the ...

, Sweden, from 9 to 13 December. After returning to Kiel, the ships of I Division went into dock for their winter repairs.

During a snowstorm on 22 March 1899, the anchor chain for the ironclad broke, allowing the ship to drift out and run aground

Ship grounding or ship stranding is the impact of a ship on seabed or

waterway side. It may be intentional, as in beaching to land crew or cargo, and careening, for maintenance or repair, or unintentional, as in a marine accident. In accidenta ...

in Strander Bucht. and the shipyard steamer towed free and back to port. On 5 April, the ship participated in the celebrations commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Eckernförde

The Battle of Eckernförde was a Danish naval assault on Schleswig. The Danes were defeated and two of their ships were lost with the surviving crew being detained.

Carsen Jensen: ''Vi, de druknede'' (oversatt av Mie Hidle), Forlaget Press, (2 ...

during the First Schleswig War. In May, I and II Divisions, along with the Reserve Division from the Baltic, went on a major cruise into the Atlantic. On the voyage out, I Division stopped in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and II Division went into Falmouth to restock their coal supplies. I Division joined II Division at Falmouth on 8 May, and the two units then departed for the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

, arriving at Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

on 12 May. There, they met the British Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

of eight battleships and four armored cruisers. The German fleet departed for Germany, stopping again in Dover on 24 May. There, they participated in the naval review celebrating Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

's 80th birthday. The fleet returned to Kiel on 31 May.

In July, the fleet conducted squadron maneuvers in the North Sea, which included coast defense exercises with soldiers from the X Corps 10th Corps, Tenth Corps, or X Corps may refer to:

France

* 10th Army Corps (France)

* X Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* X Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* X ...

. On 16 August, the fleet assembled in Danzig once again for the annual autumn maneuvers. The exercises started in the Baltic and on 30 August the fleet passed through the Kattegat and Skagerrak and steamed into the North Sea for further maneuvers in the German Bight, which lasted until 7 September. After a third phase of the maneuvers in the Kattegat and the Great Belt from 8 to 26 September, the fleet went into port for annual maintenance. The year 1900 began with the usual routine of individual and divisional exercises. In the second half of March, the squadrons met in Kiel, followed by torpedo and gunnery practice in April and a voyage to the eastern Baltic. From 7 to 26 May, the fleet went on a major training cruise to the northern North Sea, which included stops in Shetland from 12 to 15 May and in Bergen from 18 to 22 May. On 8 July, the ships of I Division were reassigned to II Division.

Boxer Uprising

During theBoxer Uprising

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

and murdered Baron Clemens von Ketteler

Clemens August Freiherr von Ketteler (22 November 1853 – 20 June 1900) was a German career diplomat. He was killed during the Boxer Rebellion.

Early life and career

Ketteler was born at Münster in western Germany on 22 November 1853 into a ...

, the German plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ...

. The widespread violence against Westerners in China led to an alliance between Germany and seven other Great Powers: the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, France, and Japan. Those soldiers who were in China at the time were too few in number to defeat the Boxers; in Beijing there was a force of slightly more than 400 officers and infantry from the armies of the eight European powers. At the time, the primary German military force in China was the East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser Squadron (naval), squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at th ...

, which consisted of the protected cruisers , , and , the small cruisers and , and the gunboats and . There was also a German 500-man detachment in Taku; combined with the other nations' units the force numbered some 2,100 men. Led by the British Admiral Edward Seymour, these men attempted to reach Beijing but were forced to stop in Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

due to heavy resistance. As a result, the Kaiser determined an expeditionary force would be sent to China to reinforce the East Asia Squadron. The expedition included and her three sisters, six cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, ten freighters, three torpedo boats, and six regiments of marines, under the command of (General Field Marshal) Alfred von Waldersee.

On 7 July, ''KAdm'' Richard von Geißler

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

, the expeditionary force commander, reported that his ships were ready for the operation, and they left two days later. The four battleships and the aviso transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and stopped in Wilhelmshaven to rendezvous with the rest of the expeditionary force. On 11 July, the force steamed out of the Jade Bight

The Jade Bight (or ''Jade Bay''; german: Jadebusen) is a bight or bay on the North Sea coast of Germany. It was formerly known simply as ''Jade'' or ''Jahde''. Because of the very low input of freshwater, it is classified as a bay rather than an ...

, bound for China. They stopped to coal at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 17–18 July and passed through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

on 26–27 July. More coal was taken on at Perim

Perim ( ar, بريم 'Barīm'', also called Mayyun in Arabic, is a volcanic island in the Strait of Mandeb at the south entrance into the Red Sea, off the south-west coast of Yemen and belonging to Yemen. It administratively belongs to Dhuba ...

in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

, and on 2 August the fleet entered the Indian Ocean. On 10 August, the ships reached Colombo, Ceylon

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

, and on 14 August they passed through the Strait of Malacca. They arrived in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

on 18 August and departed five days later, reaching Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

on 28 August. Two days later, the expeditionary force stopped in the outer roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5- ...

at Wusong, downriver from Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

.

By the time the German fleet had arrived, the siege of Beijing had already been lifted by forces from other members of the Eight-Nation Alliance that had formed to deal with the Boxers. Nevertheless, took up patrol duties in the area surrounding the mouth of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

, and in October participated in the occupations of the coastal fortification

300px, Castillo San Felipe de Barajas in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, an example of an Early Modern coastal defense

Coastal defence (or defense) and coastal fortification are measures taken to provide protection against military attack at or ...

s protecting the cities of Shanhaiguan

Shanhai Pass or Shanhaiguan () is one of the major passes in the Great Wall of China, being the easternmost stronghold along the Ming Great Wall, and commands the narrowest choke point in the Liaoxi Corridor. It is located in Shanhaiguan Di ...

and Qinhuangdao before returning to the Yangtze. Since the situation had calmed, the four battleships were sent to Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

or Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, Japan, in late 1900 and early 1901 for overhauls; went to Hong Kong for her overhaul in January and February 1901. After the work was completed, she steamed to Qingdao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

in the German Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory

The Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory was a German leased territory in Imperial and Early Republican China from 1898 to 1914. Covering an area of , it centered on Jiaozhou ("Kiautschou") Bay on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula (g ...

, where she took part in training exercises with the rest of the expeditionary force.

On 26 May, the German high command recalled the expeditionary force to Germany. The fleet took on supplies in Shanghai and departed Chinese waters on 1 June. The ships stopped in Singapore from 10 to 15 June and took on coal before proceeding to Colombo, where they stayed from 22 to 26 June. Steaming against the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

s forced the fleet to stop in Mahé, Seychelles

Mahé is the largest island of Seychelles, with an area of , lying in the northeast of the Seychellean nation in the Somali Sea part of the Indian Ocean. The population of Mahé was 77,000, as of the 2010 census. It contains the capital city ...

, to take on more coal. The ships then stopped for a day each to take on coal in Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

and Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

. On 1 August they reached Cadiz, and then met with I Division and steamed back to Germany together. They separated after reaching Helgoland, and on 11 August, after reaching the Jade roadstead, the ships of the expeditionary force were visited by Koester, who was now the Inspector General of the Navy. The following day the expeditionary fleet was dissolved. In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks.

1901–1914

Upon their return, and her sisters were assigned to I Squadron. On 21 August, the annual fleet maneuvers began; these were interrupted on 11 September when Nicholas II visited the fleet while on another visit to Germany. The ships conducted a naval review for his visit in the Putziger Wiek. For the remainder of the maneuvers, the navy cooperated with theGerman Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

in joint exercises in West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

that included the ships' (marines), and I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Arm ...

and XVII Corps. Later in the year, took part in a winter cruise, followed by a period in the shipyard in Wilhelmshaven for periodic maintenance. The year 1902 followed the routine pattern of individual, unit, and fleet training, along with a major cruise to Norway and Scotland, which concluded by passing through the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. After completing the fleet maneuvers in August and September, was decommissioned on 23 October. The ship's crew were sent to man the newly commissioned battleship , which took her place in I Squadron.

In the early 1900s, the four s were taken into the drydocks at the in Wilhelmshaven for major reconstruction. was modernized between 1903 and 1904. During the modernization, a second conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

was added in the aft superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, along with a gangway

Broadly speaking, a gangway is a passageway through which to enter or leave. Gangway may refer specifically refer to:

Passageways

* Gangway (nautical), a passage between the quarterdeck and the forecastle of a ship, and by extension, a passage th ...

. and the other ships had their boilers replaced with newer models, and also had the hamper amidships reduced. She was recommissioned on 4 April 1905 and was assigned to II Squadron of what was now renamed the Active Battlefleet, though she remained in service only briefly. She participated in the normal routine of training exercises through 1905, 1906, and 1907, before being decommissioned again on 30 September 1907. During this period, the only noteworthy incident involving was a minor grounding outside Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

that did not inflict any damage on the ship. Upon her second decommissioning, her crew was again sent to staff a new battleship, this time . was thereafter assigned to the Reserve Formation of the North Sea.

By 1910, the first dreadnought battleships began to enter service with the German fleet, rendering older vessels like obsolescent. That year, she temporarily returned to service with III Squadron to take part in the annual fleet maneuvers. After the exercises ended, she returned to what was now the Reserve Division of the North Sea, where she conducted further training. In mid-1911, she was transferred to the Training and Experimental Ships Unit, where she participated in training exercises in the Baltic. again temporarily returned to III Squadron for the fleet maneuvers in August and September, and on 16 October she was again decommissioned. In 1912, she was allocated to the (Baltic Sea Naval Station), where she remained inactive for the following two years.

World War I and subsequent activity

At the outbreak of

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, was reactivated and assigned to V Squadron, which was initially tasked with coastal defense duties in the North Sea. In mid-September, V Squadron was transferred to the Baltic, under the command of Prince Henry. He initially planned to launch a major amphibious assault on Windau

Ventspils (; german: Windau, ; see #Other names, other names) is a state city in northwestern Latvia in the historical Courland region of Latvia, and is the sixth largest city in the country. At the beginning of 2020, Ventspils had a population ...

, but a shortage of transports forced a revision of the plan. Instead, V Squadron was to carry the landing force, but this too was cancelled after Heinrich received false reports of British warships having entered the Baltic on 25 September. and the rest of the squadron returned to Kiel the following day, disembarked the landing force, and then proceeded to the North Sea, where they resumed guard ship duties. Before the end of the year, V Squadron was once again transferred to the Baltic. Prince Henry next ordered a foray toward Gotland

Gotland (, ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a province, county, municipality, and diocese. The province includes the islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to the ...

. On 26 December, the battleships rendezvoused with the Baltic cruiser division in the Bay of Pomerania and then departed on the sortie. Two days later, the fleet arrived off Gotland to show the German flag, and was back in Kiel by 30 December.

The squadron returned to the North Sea for guard duties, but was withdrawn from front-line service in February 1915. Shortages of trained crews in the High Seas Fleet, coupled with the risk of operating older ships in wartime, necessitated the deactivation of the V Squadron ships. had her crew reduced in Kiel, and she was briefly assigned to the reserve division in the Baltic. From July to December, she underwent shipyard maintenance, before being transferred to Libau. On 20 December, she was decommissioned there, for use as a water distillation

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separation process, separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distilla ...

and barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

. Her heavy guns were removed for use in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, but there is no record of them ever having been shipped to the Ottomans. Near the end of the war, was taken back to Danzig, where work began to convert her into a target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammuniti ...

, but the war ended before the reconstruction was completed. was struck from the naval register on 13 May 1919 and sold for scrapping. The ship was purchased by , a shipbreaking firm headquartered in Berlin, and she was then broken up for scrap

Scrap consists of Recycling, recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap Waste valorization, has monetary ...

in Danzig.

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Brandenburg Brandenburg-class battleships Ships built in Stettin 1891 ships World War I battleships of Germany