Roman navy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The naval forces of the ancient Roman state ( la, Classis, lit=fleet) were instrumental in the Roman conquest of the

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in naval tactics, which required great maneuverability and experience. They, therefore, employed a novel weapon that transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the '' corvus'', possibly developed earlier by the Syracusans against the

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in naval tactics, which required great maneuverability and experience. They, therefore, employed a novel weapon that transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the '' corvus'', possibly developed earlier by the Syracusans against the

After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterranean had shifted from Carthage to Rome. This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the

After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterranean had shifted from Carthage to Rome. This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the

Rome was now the undisputed master of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze from defeated Carthage to the

Rome was now the undisputed master of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze from defeated Carthage to the

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the  Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on galley slaves. Slaves were employed only in times of pressing manpower demands or extreme emergency, and even then, they were freed first.Casson (1991), p. 188 In Imperial times, non-

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on galley slaves. Slaves were employed only in times of pressing manpower demands or extreme emergency, and even then, they were freed first.Casson (1991), p. 188 In Imperial times, non-

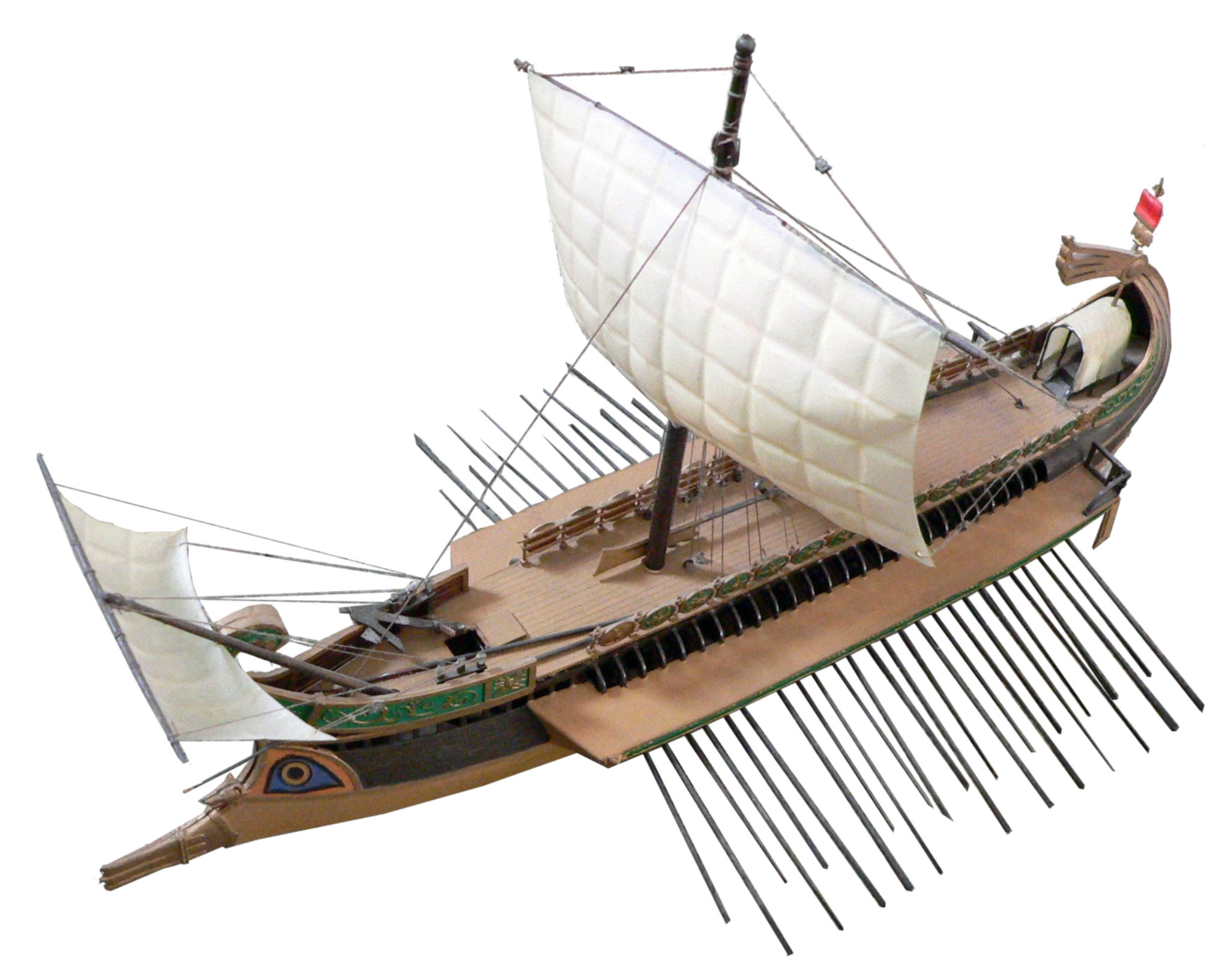

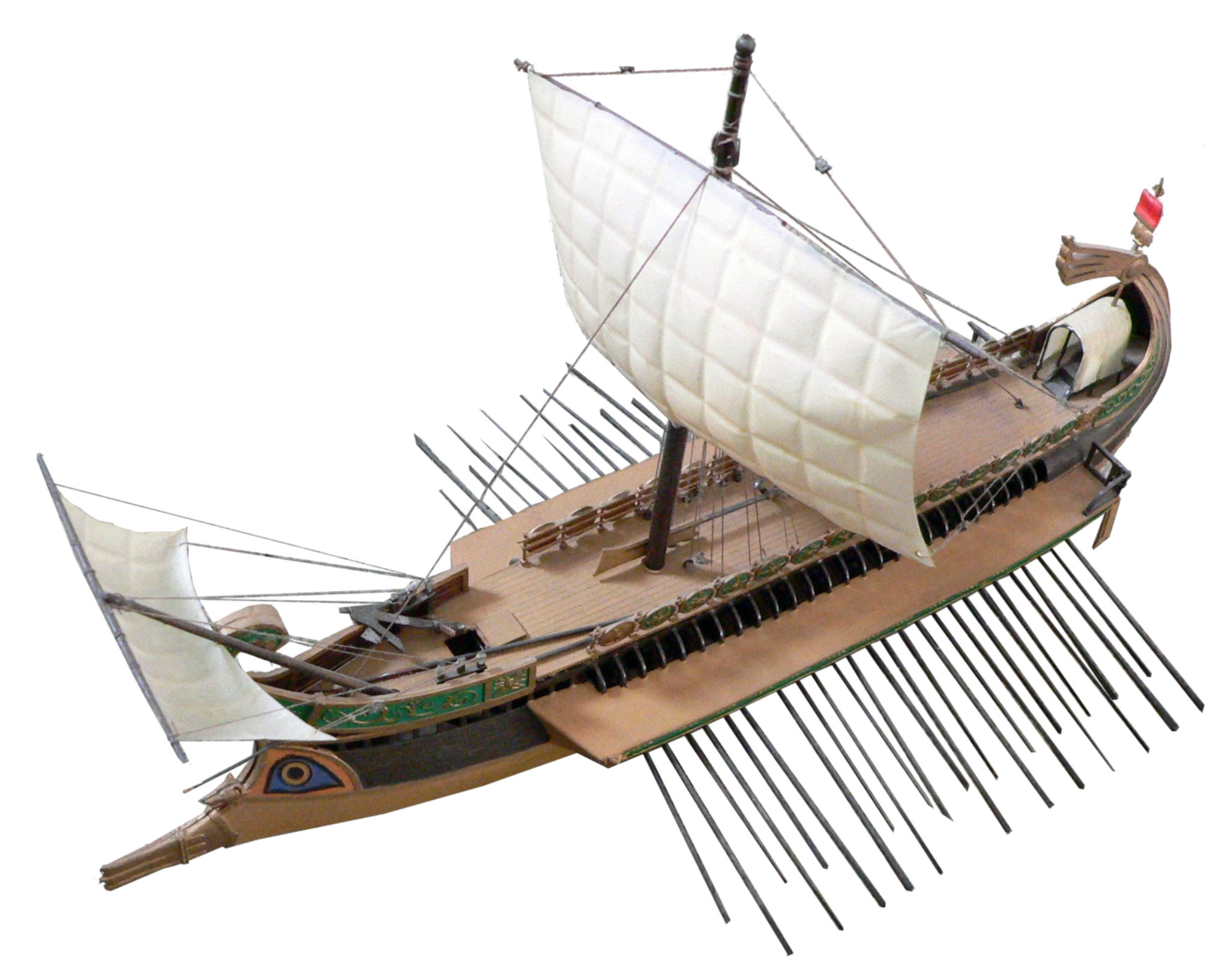

The generic Roman term for an oar-driven galley warship was "long ship" (Latin: ''navis longa'', Greek: ''naus makra''), as opposed to the sail-driven ''navis oneraria'' (from ''onus, oneris: burden''), a merchant vessel, or the minor craft (''navigia minora'') like the ''scapha''.

The navy consisted of a wide variety of different classes of warships, from heavy polyremes to light raiding and scouting vessels. Unlike the rich Hellenistic Successor kingdoms in the East however, the Romans did not rely on heavy warships, with quinqueremes (Gk. ''pentērēs''), and to a lesser extent quadriremes (Gk. ''tetrērēs'') and

The generic Roman term for an oar-driven galley warship was "long ship" (Latin: ''navis longa'', Greek: ''naus makra''), as opposed to the sail-driven ''navis oneraria'' (from ''onus, oneris: burden''), a merchant vessel, or the minor craft (''navigia minora'') like the ''scapha''.

The navy consisted of a wide variety of different classes of warships, from heavy polyremes to light raiding and scouting vessels. Unlike the rich Hellenistic Successor kingdoms in the East however, the Romans did not rely on heavy warships, with quinqueremes (Gk. ''pentērēs''), and to a lesser extent quadriremes (Gk. ''tetrērēs'') and  This prominence of lighter craft in the historical narrative is perhaps best explained in light of subsequent developments. After Actium, the operational landscape had changed: for the remainder of the Principate, no opponent existed to challenge Roman naval hegemony, and no massed naval confrontation was likely. The tasks at hand for the Roman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions. Lighter ships were far better suited to these tasks, and after the reorganization of the fleet following Actium, the largest ship kept in service was a hexareme, the flagship of the ''

This prominence of lighter craft in the historical narrative is perhaps best explained in light of subsequent developments. After Actium, the operational landscape had changed: for the remainder of the Principate, no opponent existed to challenge Roman naval hegemony, and no massed naval confrontation was likely. The tasks at hand for the Roman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions. Lighter ships were far better suited to these tasks, and after the reorganization of the fleet following Actium, the largest ship kept in service was a hexareme, the flagship of the ''

In

In

After the end of the civil wars, Augustus reduced and reorganized the Roman armed forces, including the navy. A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modern

After the end of the civil wars, Augustus reduced and reorganized the Roman armed forces, including the navy. A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modern

The ''Classis Pannonica'' and the ''Classis Moesica'' were broken up into several smaller squadrons, collectively termed ''Classis Histrica'', authority of the frontier commanders ('' duces''). with bases at Mursa in Pannonia II,''Notitia Dignitatum''

The ''Classis Pannonica'' and the ''Classis Moesica'' were broken up into several smaller squadrons, collectively termed ''Classis Histrica'', authority of the frontier commanders ('' duces''). with bases at Mursa in Pannonia II,''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Occ.'', XXXII.

/ref> Florentia in Pannonia Valeria,''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Occ.'', XXXIII.

/ref> Arruntum in

''Pars Occ.'', XXXIV.

/ref> Viminacium in Moesia I''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XLI.

/ref> and Aegetae in Dacia ripensis.''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XLII.

/ref> Smaller fleets are also attested on the tributaries of the Danube: the ''Classis Arlapensis et Maginensis'' (based at Arelape and Comagena) and the ''Classis Lauriacensis'' (based at Lauriacum) in Pannonia I, the ''Classis Stradensis et Germensis'', based at Margo in Moesia I, and the ''Classis Ratianensis'', in Dacia ripensis. The naval units were complemented by port garrisons and marine units, drawn from the army. In the Danube frontier these were: * In Pannonia I and Noricum ripensis, naval detachments (''milites liburnarii'') of the ''legio'' XIV ''Gemina'' and the ''legio'' X ''Gemina'' at

''Pars Orient.'', XL.

/ref> * In Scythia Minor, marines ('' muscularii'') of ''legio'' II ''Herculia'' at Inplateypegiis and sailors ('' nauclarii'') at Flaviana.''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XXXIX.

/ref>

''Pars Occ.'', XLII.

/ref> * The '' Classis Anderetianorum'', based at Parisii (Paris) and operating in the

''Pars Occ.'', XXXVIII.

/ref> * The '' Classis Venetum'', based at It is notable that, with the exception of the praetorian fleets (whose retention in the list does not necessarily signify an active status), the old fleets of the Principate are missing. The ''Classis Britannica'' vanishes under that name after the mid-3rd century; its remnants were later subsumed in the

It is notable that, with the exception of the praetorian fleets (whose retention in the list does not necessarily signify an active status), the old fleets of the Principate are missing. The ''Classis Britannica'' vanishes under that name after the mid-3rd century; its remnants were later subsumed in the

The Roman Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 350 BC–AD 475

Pen and Sword. .''

The Imperial fleet of Misenum

''Roman-Empire.net''

''HistoryNet.com'' *

' o

*

', the museum of Roman merchant ships found in Fiumicino (Rome) *

Diana Nemorensis

', Caligula's ships in the lake of Nemi.

* ttp://terraromana.org/navis/Forum/index.php Forum Navis Romana {{Authority control

Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

, but it never enjoyed the prestige of the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period o ...

s. Throughout their history, the Romans remained a primarily land-based people and relied partially on their more nautically inclined subjects, such as the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

and the Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

, to build their ships. Because of that, the navy was never completely embraced by the Roman state, and deemed somewhat "un-Roman".

In antiquity, navies and trading fleets did not have the logistical autonomy that modern ships and fleets possess, and unlike modern naval forces, the Roman navy even at its height never existed as an autonomous service but operated as an adjunct to the Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

.

During the course of the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

, the Roman navy was massively expanded and played a vital role in the Roman victory and the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

's eventual ascension to hegemony in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. In the course of the first half of the 2nd century BC, Rome went on to destroy Carthage and subdue the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean, achieving complete mastery of the inland sea, which they called '' Mare Nostrum''. The Roman fleets were again prominent in the 1st century BC in the wars against the pirates, and in the civil wars that brought down the Republic, whose campaigns ranged across the Mediterranean. In 31 BC, the great naval Battle of Actium ended the civil wars

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

culminating in the final victory of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

and the establishment of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

.

During the Imperial period, the Mediterranean became largely a peaceful "Roman lake". In the absence of a maritime enemy, the navy was reduced mostly to patrol, anti-piracy and transport duties. By far, the navy's most vital task was to ensure Roman grain imports were shipped and delivered to the capital unimpeded across the Mediterranean. The navy also manned and maintained craft on major frontier rivers such as the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

and the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

for supplying the army.

On the fringes of the Empire, in new conquests or, increasingly, in defense against barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less ...

invasions, the Roman fleets were still engaged in open warfare. The decline of the Empire in the 3rd century took a heavy toll on the navy, which was reduced to a shadow of its former self, both in size and in combat ability. As successive waves of the '' Völkerwanderung'' crashed on the land frontiers of the battered Empire, the navy could only play a secondary role. In the early 5th century, the Roman frontiers were breached, and barbarian kingdoms appeared on the shores of the western Mediterranean. One of them, the Vandal Kingdom with its capital at Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, raised a navy of its own and raided the shores of the Mediterranean, even sacking Rome, while the diminished Roman fleets were incapable of offering any resistance. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the late 5th century. The navy of the surviving eastern Roman Empire is known as the Byzantine navy

The Byzantine navy was the naval force of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. Like the empire it served, it was a direct continuation from its Imperial Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state than ...

.

History

Early Republic

The exact origins of the Roman fleet are obscure. A traditionally agricultural and land-based society, the Romans rarely ventured out to sea, unlike their Etruscan neighbours. There is evidence of Roman warships in the early 4th century BC, such as mention of a warship that carried an embassy toDelphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

in 394 BC, but at any rate, the Roman fleet, if it existed, was negligible. The traditional birth date of the Roman navy is set at ca. 311 BC, when, after the conquest of Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

, two new officials, the ''duumviri navales The Duumviri navales, literally two men dealing with naval matters, were two naval officers elected by the people of Rome to repair and equip the Roman fleet. Both Duumviri navales were assigned to one Roman consul, and each controlled 20 ships. It ...

classis ornandae reficiendaeque causa'', were tasked with the maintenance of a fleet. As a result, the Republic acquired its first fleet, consisting of 20 ships, most likely trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

s, with each ''duumvir'' commanding a squadron of 10 ships. However, the Republic continued to rely mostly on her legions for expansion in Italy; the navy was most likely geared towards combating piracy and lacked experience in naval warfare, being easily defeated in 282 BC by the Tarentines.

This situation continued until the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

: the main task of the Roman fleet was patrolling along the Italian coast and rivers, protecting seaborne trade from piracy. Whenever larger tasks had to be undertaken, such as the naval blockade of a besieged city, the Romans called on the allied Greek cities of southern Italy, the '' socii navales'', to provide ships and crews.Goldsworthy (2003), p. 34 It is possible that the supervision of these maritime allies was one of the duties of the four new '' praetores classici'', who were established in 267 BC.Goldsworthy (2000), p. 97

First Punic War

The first Roman expedition outside mainland Italy was against the island ofSicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in 265 BC. This led to the outbreak of hostilities with Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, which would last until 241 BC. At the time, the Punic city was the unchallenged master of the western Mediterranean, possessing a long maritime and naval experience and a large fleet. Although Rome had relied on her legions for the conquest of Italy, operations in Sicily had to be supported by a fleet, and the ships available by Rome's allies were insufficient. Thus in 261 BC, the Roman Senate set out to construct a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. According to Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme, and used it as a blueprint for their own ships. The new fleets were commanded by the annually elected Roman magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

, but naval expertise was provided by the lower officers, who continued to be provided by the ''socii'', mostly Greeks. This practice was continued until well into the Empire, something also attested by the direct adoption of numerous Greek naval terms.Webster & Elton (1998), p. 166

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in naval tactics, which required great maneuverability and experience. They, therefore, employed a novel weapon that transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the '' corvus'', possibly developed earlier by the Syracusans against the

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in naval tactics, which required great maneuverability and experience. They, therefore, employed a novel weapon that transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the '' corvus'', possibly developed earlier by the Syracusans against the Athenians

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. This was a long plank with a spike for hooking onto enemy ships. Using it as a boarding bridge, marines were able to board

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard, a ty ...

an enemy ship, transforming sea combat into a version of land combat, where the Roman legionaries had the upper hand. However, it is believed that the ''Corvus weight made the ships unstable, and could capsize a ship in rough seas.Goldsworthy (2003), p. 38

Although the first sea engagement of the war, the Battle of the Lipari Islands in 260 BC, was a defeat for Rome, the forces involved were relatively small. Through the use of the ''Corvus'', the fledgling Roman navy under Gaius Duilius

Gaius Duilius ( 260–231 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. As consul in 260 BC, during the First Punic War, he won Rome's first ever victory at sea by defeating the Carthaginians at the Battle of Mylae. He later served as censor in 258, a ...

won its first major engagement later that year at the Battle of Mylae

The Battle of Mylae took place in 260 BC during the First Punic War and was the first real naval battle between Carthage and the Roman Republic. This battle was key in the Roman victory of Mylae (present-day Milazzo) as well as Sicily itself. It ...

. During the course of the war, Rome continued to be victorious at sea: victories at Sulci (258 BC) and Tyndaris (257 BC) were followed by the massive Battle of Cape Ecnomus, where the Roman fleet under the consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus

Marcus Atilius Regulus () was a Roman statesman and general who was a consul of the Roman Republic in 267 BC and 256 BC. Much of his career was spent fighting the Carthaginians during the first Punic War. In 256 BC, he and Lucius ...

and Lucius Manlius inflicted a severe defeat on the Carthaginians. This string of successes allowed Rome to push the war further across the sea to Africa and Carthage itself. Continued Roman success also meant that their navy gained significant experience, although it also suffered a number of catastrophic losses due to storms, while conversely, the Carthaginian navy suffered from attrition.

The Battle of Drepana in 249 BC resulted in the only major Carthaginian sea victory, forcing the Romans to equip a new fleet from donations by private citizens. In the last battle of the war, at Aegates Islands in 241 BC, the Romans under Gaius Lutatius Catulus displayed superior seamanship to the Carthaginians, notably using their rams rather than the now-abandoned ''Corvus'' to achieve victory.

Illyria and the Second Punic War

After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterranean had shifted from Carthage to Rome. This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the

After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterranean had shifted from Carthage to Rome. This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

n pirates in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

. The Illyrian Wars

The Illyro-Roman Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ardiaei kingdom. In the ''First Illyrian War'', which lasted from 229 BC to 228 BC, Rome's concern was that the trade across the Adriatic Sea increased after the ...

marked Rome's first involvement with the affairs of the Balkan peninsula.Gruen (1984), p. 359. Initially, in 229 BC, a fleet of 200 warships was sent against Queen Teuta

Teuta ( Illyrian: *''Teutana'', 'mistress of the people, queen'; grc, Τεύτα; lat, Teuta) was the queen regent of the Ardiaei tribe in Illyria, who reigned approximately from 231 BC to 228/227 BC.

Following the death of her spouse Agr ...

, and swiftly expelled the Illyrian garrisons from the Greek coastal cities of modern-day Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

. Ten years later, the Romans sent another expedition in the area against Demetrius of Pharos, who had rebuilt the Illyrian navy and engaged in piracy up into the Aegean. Demetrius was supported by Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon a ...

, who had grown anxious at the expansion of Roman power in Illyria. The Romans were again quickly victorious and expanded their Illyrian protectorate, but the beginning of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

(218–201 BC) forced them to divert their resources westwards for the next decades.

Due to Rome's command of the seas, Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

, Carthage's great general, was forced to eschew a sea-borne invasion, instead choosing to bring the war over land to the Italian peninsula. Unlike the first war, the navy played little role on either side in this war. The only naval encounters occurred in the first years of the war, at Lilybaeum

Marsala (, local ; la, Lilybaeum) is an Italian town located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth in Sicily.

The town is famous for the docking of Gius ...

(218 BC) and the Ebro River (217 BC), both resulting Roman victories. Despite an overall numerical parity, for the remainder of the war the Carthaginians did not seriously challenge Roman supremacy. The Roman fleet was hence engaged primarily with raiding the shores of Africa and guarding Italy, a task which included the interception of Carthaginian convoys of supplies and reinforcements for Hannibal's army, as well as keeping an eye on a potential intervention by Carthage's ally, Philip V. The only major action in which the Roman fleet was involved was the siege of Syracuse in 214–212 BC with 130 ships under Marcus Claudius Marcellus. The siege is remembered for the ingenious inventions of Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

, such as mirrors that burned ships or the so-called "Claw of Archimedes

The Claw of Archimedes ( grc, Ἁρπάγη, translit=harpágē, lit=snatcher; also known as the iron hand) was an ancient weapon devised by Archimedes to defend the seaward portion of Syracuse's city wall against amphibious assault. Although it ...

", which kept the besieging army at bay for two years. A fleet of 160 vessels was assembled to support Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military co ...

' army in Africa in 202 BC, and, should his expedition fail, evacuate his men. In the event, Scipio achieved a decisive victory at Zama, and the subsequent peace stripped Carthage of its fleet.

Operations in the East

Rome was now the undisputed master of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze from defeated Carthage to the

Rome was now the undisputed master of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze from defeated Carthage to the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

world. Small Roman forces had already been engaged in the First Macedonian War, when, in 214 BC, a fleet under Marcus Valerius Laevinus Marcus Valerius Laevinus (c. 260 BC200 BC) was a Roman consul and commander who rose to prominence during the Second Punic War and corresponding First Macedonian War. A member of the ''gens Valeria'', an old patrician family believed to have migrat ...

had successfully thwarted Philip V from invading Illyria with his newly built fleet. The rest of the war was carried out mostly by Rome's allies, the Aetolian League and later the Kingdom of Pergamon, but a combined Roman–Pergamene fleet of ca. 60 ships patrolled the Aegean until the war's end in 205 BC. In this conflict, Rome, still embroiled in the Punic War, was not interested in expanding her possessions, but rather in thwarting the growth of Philip's power in Greece. The war ended in an effective stalemate, and was renewed in 201 BC, when Philip V invaded Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. A naval battle

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

off Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mast ...

ended in a costly victory for the Pergamene– Rhodian alliance, but the Macedonian fleet lost many warships, including its flagship, a ''deceres''. Soon after, Pergamon and Rhodes appealed to Rome for help, and the Republic was drawn into the Second Macedonian War. In view of the massive Roman naval superiority, the war was fought on land, with the Macedonian fleet, already weakened at Chios, not daring to venture out of its anchorage at Demetrias. After the crushing Roman victory at Cynoscephalae, the terms imposed on Macedon were harsh, and included the complete disbandment of her navy.

Almost immediately following the defeat of Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

, Rome became embroiled in a war with the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

. This war too was decided mainly on land, although the combined Roman–Rhodian navy also achieved victories over the Seleucids at Myonessus and Eurymedon. These victories, which were invariably concluded with the imposition of peace treaties that prohibited the maintenance of anything but token naval forces, spelled the disappearance of the Hellenistic royal navies, leaving Rome and her allies unchallenged at sea. Coupled with the final destruction of Carthage, and the end of Macedon's independence, by the latter half of the 2nd century BC, Roman control over all of what was later to be dubbed '' mare nostrum'' ("our sea") had been established. Subsequently, the Roman navy was drastically reduced, depending on its Socii navales.Connolly (1998), p. 273

Late Republic

Mithridates and the pirate threat

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

In the absence of a strong naval presence however, piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

flourished throughout the Mediterranean, especially in Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

, but also in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and other places, further reinforced by money and warships supplied by King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who hoped to enlist their aid in his wars against Rome. In the First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War (89–85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule were led by Mithridat ...

(89–85 BC), Sulla had to requisition ships wherever he could find them to counter Mithridates' fleet. Despite the makeshift nature of the Roman fleet however, in 86 BC Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingd ...

defeated the Pontic navy at Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province. With an area of it is the third l ...

.Starr (1989), p. 62

Immediately after the end of the war, a permanent force of ca. 100 vessels was established in the Aegean from the contributions of Rome's allied maritime states. Although sufficient to guard against Mithridates, this force was totally inadequate against the pirates, whose power grew rapidly. Over the next decade, the pirates defeated several Roman commanders, and raided unhindered even to the shores of Italy, reaching Rome's harbor, Ostia. According to the account of Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, "the ships of the pirates numbered more than a thousand, and the cities captured by them four hundred." Their activity posed a growing threat for the Roman economy, and a challenge to Roman power: several prominent Romans, including two praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

s with their retinue and the young Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, were captured and held for ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French ''rançon'' from Latin ''re ...

. Perhaps most important of all, the pirates disrupted Rome's vital lifeline, namely the massive shipments of grain and other produce from Africa and Egypt that were needed to sustain the city's population.

The resulting grain shortages were a major political issue, and popular discontent threatened to become explosive. In 74 BC, with the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of th ...

, Marcus Antonius

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

(the father of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

) was appointed ''praetor'' with extraordinary '' imperium'' against the pirate threat, but signally failed in his task: he was defeated off Crete in 72 BC, and died shortly after. Finally, in 67 BC the '' Lex Gabinia'' was passed in the Plebeian Council

The ''Concilium Plebis'' ( English: Plebeian Council., Plebeian Assembly, People's Assembly or Council of the Plebs) was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly ...

, vesting Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

with unprecedented powers and authorizing him to move against them. In a massive and concerted campaign, Pompey cleared the seas of the pirates in only three months. Afterwards, the fleet was reduced again to policing duties against intermittent piracy.

Caesar and the Civil Wars

In 56 BC, for the first time a Roman fleet engaged in battle outside the Mediterranean. This occurred duringJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

's Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland). Gallic, Germanic, and British tribes fought to defend their homel ...

, when the maritime tribe of the Veneti rebelled against Rome. Against the Veneti, the Romans were at a disadvantage, since they did not know the coast, and were inexperienced in fighting in the open sea with its tides and currents. Furthermore, the Veneti ships were superior to the light Roman galleys. They were built of oak and had no oars, being thus more resistant to ramming. In addition, their greater height gave them an advantage in both missile exchanges and boarding actions. In the event, when the two fleets encountered each other in Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

, Caesar's navy, under the command of D. Brutus, resorted to the use of hooks on long poles, which cut the halyards supporting the Veneti sails. Immobile, the Veneti ships were easy prey for the legionaries who boarded them, and fleeing Veneti ships were taken when they became becalmed by a sudden lack of winds. Having thus established his control of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

, in the next years Caesar used this newly built fleet to carry out two invasions of Britain.

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the civil wars

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

that ended the Republic. In the East, the Republican faction quickly established its control, and Rhodes, the last independent maritime power in the Aegean, was subdued by Gaius Cassius Longinus

Gaius Cassius Longinus (c. 86 BC – 3 October 42 BC) was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the co ...

in 43 BC, after its fleet was defeated off Kos. In the West, against the triumvirs stood Sextus Pompeius, who had been given command of the Italian fleet by the Senate in 43 BC. He took control of Sicily and made it his base, blockading Italy and stopping the politically crucial supply of grain from Africa to Rome. After suffering a defeat from Sextus in 42 BC, Octavian initiated massive naval armaments, aided by his closest associate, Marcus Agrippa: ships were built at Ravenna and Ostia, the new artificial harbor of Portus Julius built at Cumae, and soldiers and rowers levied, including over 20,000 manumitted slaves. Finally, Octavian and Agrippa defeated Sextus in the Battle of Naulochus in 36 BC, putting an end to all Pompeian resistance.

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

and Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

, Queen of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Antony had assembled 500 ships against Octavian's 400 ships. This last naval battle of the Roman Republic definitively established Octavian as the sole ruler over Rome and the Mediterranean world. In the aftermath of his victory, he formalized the Fleet's structure, establishing several key harbors in the Mediterranean (see below). The now fully professional navy had its main duties consist of protecting against piracy, escorting troops and patrolling the river frontiers of Europe. It remained however engaged in active warfare in the periphery of the Empire.

Principate

Operations under Augustus

UnderAugustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

and after the conquest of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

there were increasing demands from the Roman economy to extend the trade lanes to India. The Arabian control of all sea routes to India was an obstacle. One of the first naval operations under ''princeps'' Augustus was therefore the preparation for a campaign on the Arabian Peninsula. Aelius Gallus

Gaius Aelius Gallus was a Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 BC. He is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) under orders of Augustus.

Life

Aelius Gallus was the 2nd ''praefect'' of Roman Eg ...

, the prefect of Egypt ordered the construction of 130 transports and subsequently carried 10,000 soldiers to Arabia. But the following march through the desert towards Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

failed and the plans for control of the Arabian peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

had to be abandoned.

At the other end of the Empire, in Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north-c ...

, the navy played an important role in the supply and transport of the legions. In 15 BC an independent fleet was installed at the Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Lak ...

. Later, the generals Drusus

Drusus may refer to:

* Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Drusus) (10 BC–AD 54), Roman emperor from 41 to 54

* Drusus Caesar (AD 8–33), adoptive grandson of Roman emperor Tiberius

* Drusus Julius Caesar (14 BC–AD 23), son of Roman emperor Tiberius

...

and Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

used the Navy extensively, when they tried to extend the Roman frontier to the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

. In 12 BC Drusus

Drusus may refer to:

* Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Drusus) (10 BC–AD 54), Roman emperor from 41 to 54

* Drusus Caesar (AD 8–33), adoptive grandson of Roman emperor Tiberius

* Drusus Julius Caesar (14 BC–AD 23), son of Roman emperor Tiberius

...

ordered the construction of a fleet of 1,000 ships and sailed them along the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

into the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

. The Frisii and Chauci had nothing to oppose the superior numbers, tactics and technology of the Romans. When these entered the river mouths of Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

and Ems, the local tribes had to surrender.

In 5 BC the Roman knowledge concerning the North and Baltic Sea was fairly extended during a campaign by Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

, reaching as far as the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

: Plinius describes how Roman naval formations came past Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possession ...

and set sail to the north-eastern coast of Denmark, and Augustus himself boasts in his '' Res Gestae'': "My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward as far as the lands of the Cimbri to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea...". The multiple naval operations north of Germania had to be abandoned after the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in the year 9 AD.

Julio-Claudian dynasty

In the years 15 and 16,Germanicus

Germanicus Julius Caesar (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19) was an ancient Roman general, known for his campaigns in Germania. The son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia the Younger, Germanicus was born into an influential branch of the pa ...

carried out several fleet operations along the rivers Rhine and Ems, without permanent results due to grim Germanic resistance and a disastrous storm. By 28, the Romans lost further control of the Rhine mouth in a succession of Frisian insurgencies. From 43 to 85, the Roman navy played an important role in the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stan ...

. The ''classis Germanica'' rendered outstanding services in multitudinous landing operations. In 46, a naval expedition made a push deep into the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

region and even travelled on the Tanais. In 47 a revolt by the Chauci, who took to piratical activities along the Gallic coast, was subdued by Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. By 57 an expeditionary corps reached Chersonesos

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

(see Charax, Crimea

Charax ( grc, Χάραξ, gen.: Χάρακος) is the largest Roman military settlement excavated in the Crimea. It was sited on a four-hectare area at the western ridge of Ai-Todor, close to the modern tourist attraction of Swallow's Nest.

The ...

).

It seems that under Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

, the navy obtained strategically important positions for trading with India; but there was no known fleet in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

. Possibly, parts of the Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

n fleet were operating as escorts for the Indian trade. In the Jewish revolt, from 66 to 70, the Romans were forced to fight Jewish ships, operating from a harbour in the area of modern Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, on Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

's Mediterranean coast. In the meantime several flotilla engagements on the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

took place.

In 68, as his reign became increasingly insecure, Nero raised ''legio'' I ''Adiutrix'' from sailors of the praetorian fleets. After Nero's overthrow, in 69, the " Year of the four emperors", the praetorian fleets supported Emperor Otho against the usurper Vitellius, and after his eventual victory, Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Emp ...

formed another legion, ''legio'' II ''Adiutrix'', from their ranks. Only in the Pontus did Anicetus, the commander of the ''Classis Pontica'', support Vitellius. He burned the fleet, and sought refuge with the Iberian tribes, engaging in piracy. After a new fleet was built, this revolt was subdued.Webster & Elton (1998), p. 164

Flavian, Antonine and Severan dynasties

During the Batavian rebellion of Gaius Julius Civilis (69–70), the rebels got hold of a squadron of the Rhine fleet by treachery, and the conflict featured frequent use of the Roman Rhine flotilla. In the last phase of the war, the British fleet and ''legio'' XIV were brought in from Britain to attack the Batavian coast, but the Cananefates, allies of the Batavians, were able to destroy or capture a large part of the fleet. In the meantime, the new Roman commander,Quintus Petillius Cerialis

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus ( AD 30 — after AD 83), otherwise known as Quintus Petillius Cerialis, was a Roman general and administrator who served in Britain during Boudica's rebellion and went on to participate in the civil wars a ...

, advanced north and constructed a new fleet. Civilis attempted only a short encounter with his own fleet, but could not hinder the superior Roman force from landing and ravaging the island of the Batavians, leading to the negotiation of a peace soon after.

In the years 82 to 85, the Romans under Gnaeus Julius Agricola launched a campaign against the Caledonians

The Caledonians (; la, Caledones or '; grc-gre, Καληδῶνες, ''Kalēdōnes'') or the Caledonian Confederacy were a Brittonic-speaking ( Celtic) tribal confederacy in what is now Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman eras.

The Gre ...

in modern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. In this context the Roman navy significantly escalated activities on the eastern Scottish coast. Simultaneously multiple expeditions and reconnaissance trips were launched. During these the Romans would capture the Orkney Islands (''Orcades'') for a short period of time and obtained information about the Shetland Islands

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

. There is some speculation about a Roman landing in Ireland, based on Tacitus reports about Agricola contemplating the island's conquest, but no conclusive evidence to support this theory has been found.

Under the Five Good Emperors

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

the navy operated mainly on the rivers; so it played an important role during Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

's conquest of Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

and temporarily an independent fleet for the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

rivers was founded. Also during the wars against the Marcomanni confederation under Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

several combats took place on the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

and the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

.

Under the aegis of the Severan dynasty, the only known military operations of the navy were carried out under Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary suc ...

, using naval assistance on his campaigns along the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, as well as in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. Thereby Roman ships reached ''inter alia'' the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

and the top of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

.

3rd century crisis

As the 3rd century dawned, the Roman Empire was at its peak. In the Mediterranean, peace had reigned for over two centuries, as piracy had been wiped out and no outside naval threats occurred. As a result, complacency had set in: naval tactics and technology were neglected, and the Roman naval system had become moribund. After 230 however and for fifty years, the situation changed dramatically. The so-called " Crisis of the Third Century" ushered a period of internal turmoil, and the same period saw a renewed series of seaborne assaults, which the imperial fleets proved unable to stem.Lewis & Runyan (1985), p. 4 In the West,Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

and Irish ships raided Britain, while the Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

raided the North Sea, forcing the Romans to abandon Frisia

Frisia is a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. The region is traditionally inhabited by the Frisians, a West G ...

. In the East, the Goths and other tribes from modern Ukraine raided in great numbers over the Black Sea.Casson (1991), p. 213 These invasions began during the rule of Trebonianus Gallus, when for the first time Germanic tribes built up their own powerful fleet in the Black Sea. Via two surprise attacks (256) on Roman naval bases in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

and near the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, numerous ships fell into the hands of the Germans, whereupon the raids were extended as far as the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

; Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

and other towns were plundered and the responsible provincial fleets were heavily debilitated. It was not until the attackers made a tactical error, that their onrush could be stopped.

In 267–270 another, much fiercer series of attacks took place. A fleet composed of Heruli and other tribes raided the coasts of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and the Pontus. Defeated off Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

by general Venerianus, the barbarians fled into the Aegean, and ravaged many islands and coastal cities, including Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

and Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

. As they retreated northwards over land, they were defeated by Emperor Gallienus at Nestos. However, this was merely the prelude to an even larger invasion that was launched in 268/269: several tribes banded together (the '' Historia Augusta'' mentions Scythians, Greuthungi, Tervingi, Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

, Peucini, Celts and Heruli) and allegedly 2,000 ships and 325,000 men strong, raided the Thracian shore, attacked Byzantium and continued raiding the Aegean as far as Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, while the main force approached Thessalonica. Emperor Claudius II however was able to defeat them at the Battle of Naissus, ending the Gothic threat for the time being.

Barbarian raids also increased along the Rhine frontier and in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

. Eutropius mentions that during the 280s, the sea along the coasts of the provinces of Belgica and Armorica was "infested with Franks and Saxons". To counter them, Maximian

Maximian ( la, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus; c. 250 – c. July 310), nicknamed ''Herculius'', was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was '' Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his ...

appointed Carausius

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius (died 293) was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and ...

as commander of the British Fleet

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. However, Carausius rose up in late 286 and seceded from the Empire with Britannia and parts of the northern Gallic coast. With a single blow Roman control of the channel and the North Sea was lost, and emperor Maximinus was forced to create a completely new Northern Fleet, but in lack of training it was almost immediately destroyed in a storm. Only in 293, under '' Caesar'' Constantius Chlorus

Flavius Valerius Constantius "Chlorus" ( – 25 July 306), also called Constantius I, was Roman emperor from 305 to 306. He was one of the four original members of the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian, first serving as caesar from 293 ...

did Rome regain the Gallic coast. A new fleet was constructed in order to cross the Channel, and in 296, with a concentric attack on Londinium

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50. It sat at a key cros ...

the insurgent province was retaken.

Late antiquity

By the end of the 3rd century, the Roman navy had declined dramatically. Although EmperorDiocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

is held to have strengthened the navy, and increased its manpower from 46,000 to 64,000 men, the old standing fleets had all but vanished, and in the civil wars that ended the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

, the opposing sides had to mobilize the resources and commandeered the ships of the Eastern Mediterranean port cities. These conflicts thus brought about a renewal of naval activity, culminating in the Battle of the Hellespont

The Battle of the Hellespont, consisting of two separate naval clashes, was fought in 324 between a Constantinian fleet, led by the eldest son of Constantine I, Crispus; and a larger fleet under Licinius' admiral, Abantus (or Amandus). Despite ...

in 324 between the forces of Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

under Caesar Crispus

Flavius Julius Crispus (; 300 – 326) was the eldest son of the Roman emperor Constantine I, as well as his junior colleague ( ''caesar'') from March 317 until his execution by his father in 326. The grandson of the ''augustus'' Constantius ...

and the fleet of Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

, which was the only major naval confrontation of the 4th century. Vegetius, writing at the end of the 4th century, testifies to the disappearance of the old praetorian fleets in Italy, but comments on the continued activity of the Danube fleet.MacGeorge (2002), pp. 306–307 In the 5th century, only the eastern half of the Empire could field an effective fleet, as it could draw upon the maritime resources of Greece and the Levant. Although the ''Notitia Dignitatum

The ''Notitia Dignitatum'' (Latin for "The List of Offices") is a document of the late Roman Empire that details the administrative organization of the Western and the Eastern Roman Empire. It is unique as one of very few surviving documents o ...

'' still mentions several naval units for the Western Empire, these were apparently too depleted to be able to carry out much more than patrol duties. At any rate, the rise of the naval power of the Vandal Kingdom under Geiseric in North Africa, and its raids in the Western Mediterranean, were practically uncontested. Although there is some evidence of West Roman naval activity in the first half of the 5th century, this is mostly confined to troop transports and minor landing operations. The historian Priscus

Priscus of Panium (; el, Πρίσκος; 410s AD/420s AD-after 472 AD) was a 5th-century Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life genera ...

and Sidonius Apollinaris affirm in their writings that by the mid-5th century, the Western Empire essentially lacked a war navy. Matters became even worse after the disastrous failure of the fleets mobilized against the Vandals in 460 and 468, under the emperors Majorian

Majorian ( la, Iulius Valerius Maiorianus; died 7 August 461) was the western Roman emperor from 457 to 461. A prominent general of the Roman army, Majorian deposed Emperor Avitus in 457 and succeeded him. Majorian was the last emperor to make ...

and Anthemius.

For the West, there would be no recovery, as the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed in 476. In the East however, the classical naval tradition survived, and in the 6th century, a standing navy was reformed. The East Roman (Byzantine) navy would remain a formidable force in the Mediterranean until the 11th century.

Organization

Crews

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on galley slaves. Slaves were employed only in times of pressing manpower demands or extreme emergency, and even then, they were freed first.Casson (1991), p. 188 In Imperial times, non-

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on galley slaves. Slaves were employed only in times of pressing manpower demands or extreme emergency, and even then, they were freed first.Casson (1991), p. 188 In Imperial times, non-citizen

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

freeborn provincials (''peregrini

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a ''peregrinus'' (Latin: ) was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. ''Peregrini'' constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centur ...

''), chiefly from nations with a maritime background such as Greeks, Phoenicians, Syrians and Egyptians, formed the bulk of the fleets' crews.

During the early Principate, a ship's crew, regardless of its size, was organized as a ''centuria