Robert Smirke (architect) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Robert Smirke (1 October 1780 – 18 April 1867) was an English

Smirke was born in London on 1 October 1780, the second son of the portrait painter Robert Smirke; he was one of twelve children.page 73, J. Mordaunt Crook: ''The British Museum A Case-study in Architectural Politics'', 1972, Pelican Books He attended Aspley School,

Smirke was born in London on 1 October 1780, the second son of the portrait painter Robert Smirke; he was one of twelve children.page 73, J. Mordaunt Crook: ''The British Museum A Case-study in Architectural Politics'', 1972, Pelican Books He attended Aspley School,

Smirke, in the view of

Smirke, in the view of

From 1825 to 1827 Smirke rebuilt the centre of the

From 1825 to 1827 Smirke rebuilt the centre of the

The second incarnation of the Covent Garden Theatre (now the Royal Opera House), built in ten months in 1808–1809. It had a symmetrical facade with a tetrastyle portico in the centre, and was the first building in London to use the Greek Doric order.page 473, John Summerson, ''Architecture in Britain 1530–1830'', 8th Edition 1991, Pelican Books The portico was flanked by four bays, the end bays being marked by pilasters with a statue in a niche between. The three bays on each side of the portico had arches on the ground floor and windows above these and a single carved relief above designed

by

The second incarnation of the Covent Garden Theatre (now the Royal Opera House), built in ten months in 1808–1809. It had a symmetrical facade with a tetrastyle portico in the centre, and was the first building in London to use the Greek Doric order.page 473, John Summerson, ''Architecture in Britain 1530–1830'', 8th Edition 1991, Pelican Books The portico was flanked by four bays, the end bays being marked by pilasters with a statue in a niche between. The three bays on each side of the portico had arches on the ground floor and windows above these and a single carved relief above designed

by

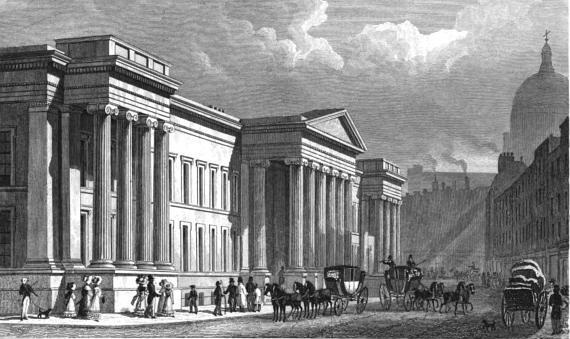

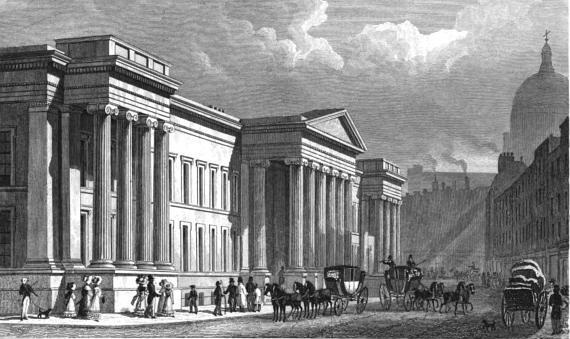

The General Post Office building in St Martins-le-Grand in the

The General Post Office building in St Martins-le-Grand in the

File:SIMPSON, W. after WALKER, E.publ1852 edited.jpg, British Museum, 1852

File:British Museum (front).jpg, Entrance portico, British Museum

File:L-british-museum-london.png, Plan of the British Museum

File:BM, Main Floor Main Entrance Hall ~ South Stairs.6.JPG, Great Staircase, British Museum

File:BM; 'MF' RM1 - The King's Library, Enlightenment 1 'Discovering the world in the 18th Century ~ View South.jpg, King's Library, British Museum

File:British Museum Room 1 Enlightenment.jpg, Bookcases in the King's Library, British Museum

File:BM, AES Egyptian Sculpture (Room 4), View North.4.JPG, Egyptian Gallery, British Museum

The

The

File:New Covent Garden Theatre Microcosm edited.jpg, Covent Garden Theatre, burnt and rebuilt

File:Lancaster House London April 2006 032.jpg, Lancaster House

File:Herbert Railton - The Inner Temple Library.jpg, Inner Temple Library

File:King's1.jpg, King's College London, east wing of Somerset House

File:London - Inner Temple.jpg, Paper Buildings, Inner Temple

The Oxford and Cambridge Club building in Pall Mall (1835–38). It is of seven bays, the ground floor is rusticated with round headed windows, the first floor is of banded rustication and the windows framed with square or half pillars, the building is of brick covered with

The Oxford and Cambridge Club building in Pall Mall (1835–38). It is of seven bays, the ground floor is rusticated with round headed windows, the first floor is of banded rustication and the windows framed with square or half pillars, the building is of brick covered with

File:A7 Roadbridge over River Eden in Carlisle - geograph.org.uk - 92889.jpg, Eden Bridge Carlisle

File:Perth Sheriff Court 2.jpg, Perth Sheriff Court

File:Crown Court - geograph.org.uk - 134109.jpg, Courts Lincoln Castle

File:Ireland - Dublin - Phoenix Park - Wellington Monument 2.jpg, Wellington Testimonial

File:Oldcouncilhousebristol.JPG, Old Council House, Bristol

File:The Parade Shopping Centre, St Mary's Place, Shrewsbury - geograph.org.uk - 117039.jpg, Former Salop Infirmary, Shrewsbury

File:CitadelCarlisle0809.jpg, Former County Courts, Carlisle

File:The cloisters and St Lawrence's Church - geograph.org.uk - 771339.jpg, The former Market House, Appleby

File:Main entrance to Shire Hall - geograph.org.uk - 694058.jpg, Gloucester Shire Hall

File:Shire Hall and war memorial - geograph.org.uk - 844672.jpg, Hereford Shire Hall

His public buildings outside London include:

*

File:The Observatory - a Fuller Folly - geograph.org.uk - 313439.jpg, Brightling Observatory

File:Luton Hoo.jpg, Luton Hoo

File:Whittingehame house.jpg, Whittingehame House

File:Normanby Hall (overview).jpg, Normanby Hall

File:Mar Hall Hotel.jpeg, Erskine House

File:Lowther Castle 01.jpg, Lowther Castle

File:Lowther Castle 02.jpg, Lowther Castle

File:Cholmondeley Castle.jpg, Cholmondeley Castle

File:Eastnor Castle 03.jpg, Eastnor Castle

File:Oulton Hall Hotel, Oulton. - geograph.org.uk - 258514.jpg, Oulton Hall

File:Armley House, Gotts Park, Upper Armley - geograph.org.uk - 922697.jpg, Armley House

File:Strathallan Castle - geograph.org.uk - 539085.jpg, Strathallan Castle

In the classical style:

*

File:St. Anne's Church, St. Ann's Crescent, Wandsworth. - geograph.org.uk - 20226.jpg, St Anne's Church, Wandsworth

File:St. Anne's Church, Wandsworth - geograph.org.uk - 1030515.jpg, St Anne's Church, Wandsworth

File:St Mary's Church, Bryanston Square, London (IoE Code 207691).JPG, St Mary's Church, Bryanston Square

File:Saint Mary's Church, Bryanston Square - geograph.org.uk - 585541.jpg, St Mary's Church, Bryanston Square

File:Church of St Philip with St Stephen, Salford.jpg, St Philip's Church, Salford

File:Stgeorgeschapel.jpg, St George's Church, Brandon Hill

File:St George, Tyldesley, north.jpg, St George's Church, Tyldesley

File:Milton Mausoleum - geograph.org.uk - 55748.jpg, The Mausoleum Milton

File:St Peter's Church - Askham - geograph.org.uk - 509275.jpg, St Peter's Church, Askham

File:St. Nicholas Church, Strood - geograph.org.uk - 1044614.jpg, St Nicholas's Church, Strood

File:Railway Street, Chatham - geograph.org.uk - 847371.jpg, St John's Church, Chatham

File:Belgrave Chapel, and West Side of Belgrave Square - Shepherd, Metropolitan Improvements (1828), p257.jpg, Belgrave Chapel on the right, demolished c. 1910

File:St. Peter, Milton Bryan - geograph.org.uk - 837314.jpg, St Peter's Church, Milton Bryan

He advised the Parliamentary

Smirke was involved in

Smirke was involved in

Smirke's work in Cumbria

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smirke, Robert 1780 births 1867 deaths Knights Bachelor 19th-century English architects Royal Academicians British neoclassical architects Greek Revival architects People associated with the British Museum Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal Robert Smirke (architect) buildings Architects from London

architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

, one of the leaders of Greek Revival architecture

The Greek Revival was an architectural style, architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United Sta ...

, though he also used other architectural styles. As architect to the Board of Works, he designed several major public buildings, including the main block and façade of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. He was a pioneer of the use of concrete foundations.

Background and training

Aspley Guise

Aspley Guise is a village and civil parish in the west of Central Bedfordshire, England. In addition to the village of Aspley Guise itself, the civil parish also includes part of the town of Woburn Sands, the rest of which is in the City of Milt ...

, Bedfordshire,page 74, J. Mordaunt Crook: ''The British Museum A Case-study in Architectural Politics'', 1972, Pelican Books where he studied Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, French and drawing

Drawing is a form of visual art in which an artist uses instruments to mark paper or other two-dimensional surface. Drawing instruments include graphite pencils, pen and ink, various kinds of paints, inked brushes, colored pencils, crayo ...

, and was made head boy at the age of 15. In May 1796 he began his study of architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

as a pupil of John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor of architecture at the R ...

but left after only a few months in early 1797 due to a personality clash with his teacher. He wrote to his father:

He (Soane) was on Monday morning in one of his amiable Tempers. Everything was slovenly that I was doing. My drawing was slovenly because it was too great a scale, my scale, also, being too long, and he finished saying the whole of it was excessively slovenly, and that I should draw it out again on the back not to waste another sheet about it.In 1796, he also began his studies at the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

, winning the Silver Medal and the Silver Palette of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

that year. He was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Academy in 1799 for his design for a ''National Museum''. After leaving Soane he depended on George Dance the Younger

George Dance the Younger RA (1 April 1741 – 14 January 1825) was an English architect and surveyor as well as a portraitist.

The fifth and youngest son of the architect George Dance the Elder, he came from a family of architects, artists an ...

and a surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

called Thomas Bush for his architectural training.

In 1801, accompanied by his elder brother Richard, he attempted to embark on a Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

, but was forced to return to England because war with France made it impossible to travel safely without fear of arrest. The short-lived Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

the following year allowed British travellers to visit France, and Smirke set off again in September of 1802 in the company of the artist William Walker, returning early in 1805. His itinerary and impressions are recorded in a series of letters and journals he wrote, many preserved in the archive of the RIBA

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

, and in the many drawings he made of buildings. In France he visited places such as Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, Lyons

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

, Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, Nimes, Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province ...

and Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

; he was particularly impressed by the various Roman monuments in the south of the country. In Italy, he passed through Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

and Siena

Siena ( , ; lat, Sena Iulia) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.

The city is historically linked to commercial and banking activities, having been a major banking center until the 13th and 14th centur ...

but spent almost two months in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

where he made the decision to visit Greece. Embarking from Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, he travelled via the Ionian Islands to Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

and the Argolid. Turning south into the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

, he saw famous sites such as Messene

Messene (Greek: Μεσσήνη 𐀕𐀼𐀙 ''Messini''), officially Ancient Messene, is a local community within the regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') of Messenia in the region (''perifereia'') of Peloponnese.

It is best known for the ...

, Megalopolis

A megalopolis () or a supercity, also called a megaregion, is a group of metropolitan areas which are perceived as a continuous urban area through common systems of transport, economy, resources, ecology, and so on. They are integrated enoug ...

, Bassai

''Passai'' (拔塞, katakana パッサイ), also ''Bassai'' (バッサイ), is the name of a group of kata practiced in different styles of martial arts, including karate and various Korean martial arts, including Taekwondo, Tang Soo Do, and So ...

and Olympia, before travelling on to Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

where he spent a month sketching the monuments. From Athens Smirke wrote to his father:

How can I by description give you any idea of the great pleasure I enjoyed in the sight of these ancient buildings of Athens! How strongly were exemplified in them the grandeur and effect of simplicity in architecture! The Temple of Thesus ( Temple of Hephaestus)... cannot but arrest the attention of everyone from its appropriate and dignified solemnity of appearance. The temple of Minerva (Following his departure from Athens, Smirke visited other famous ancient sites such as Thebes and Delphi. Smirke's return from Greece was complicated by the resumption of war between Britain and France, and he had to travel via Sicily and Malta to avoid the risk of capture by enemy troops. However, he managed to revisit Rome and Naples (seeing the ruins ofParthenon The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...)... strikes one in the same way with its grandeur and majesty. We were a month there. The impression made upon my mind... had not in that time in the least weakened by being frequently repeated and I could with pleasure spend a much longer time there, while those in Rome (with few exceptions) not only soon grow in some degree uninteresting but have now entirely sunk into disregard and contempt in my mind. All that I could do in Athens was to make some views of them...hoping that they will serve as a memorandum to me of what I think should always be a model.'

Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was burie ...

and Paestum

Paestum ( , , ) was a major ancient Greek city on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). The ruins of Paestum are famous for their three ancient Greek temples in the Doric order, dating from about 550 to 450 BC, whi ...

) and other cities as he travelled up the Italian peninsula towards Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a thr ...

and Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

. Crossing into Austrian territory, he visited Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol and the fifth-largest city in Austria. On the River Inn, at its junction with the Wipp Valley, which provides access to the Brenner Pass to the south, it had a p ...

, Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Austro-Bavarian) is the fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the Roman settlement of ''Iuvavum''. Salzburg was founded ...

, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

before moving on to Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, returning to England via Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possession ...

in early January 1805.

His extensive travels through most of the major centres of Europe provided him with an unparalleled insight on ancient, Renaissance and more recent architecture, though his poor opinion of many of the more recent buildings he saw, even in Rome and Paris, combined with the overwhelming impact of ancient Greek structures, triggered a significant shift in his architectural tastes. Whereas his earlier designs had been in the conventional French Neo-Classical idiom of the time, influenced by George Dance the Younger

George Dance the Younger RA (1 April 1741 – 14 January 1825) was an English architect and surveyor as well as a portraitist.

The fifth and youngest son of the architect George Dance the Elder, he came from a family of architects, artists an ...

and John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor of architecture at the R ...

, most of the classical-style buildings he designed as a professional architect were firmly rooted in the Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but a ...

. Unlike some of his contemporaries he did not visit Turkey. His knowledge of its ancient buildings, which were crucial to his designs in the 1820s such as the British Museum, was derived from publications such as ''Ionian Antiquities'' of 1769 by Richard Chandler, William Pars

William Pars (28 February 1742 – 1782) was an English watercolour portrait and landscape painter, draughtsman, and illustrator.

Life and works

Pars was born in London, the son of a metal engraver. He studied at "Shipley's Drawing Schoo ...

and Nicholas Revett

Nicholas Revett (1720–1804) was a British architect. Revett is best known for his work with James "Athenian" Stuart documenting the ruins of ancient Athens. He is sometimes described as an amateur architect, but he played an important role in t ...

.

During his Grand Tour, Smirke made drawings and watercolours of many buildings, including most of the surviving ancient structures in Athens and the Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

. Most however were never published, and few were exhibited in his lifetime, though a considerable is preserved in the RIBA

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

, the Paul Mellon Center for British Art, the British Museum, and other collections.

Career

In 1805, Smirke became a member of theSociety of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

and the Architects' Club. His first official appointment came in 1807 when he was made architect to The Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's oldest company and the official maker of British coins.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly owned by His Majesty's Treasury and is under an exclus ...

. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy on 7 November 1808, and a full Academician on 11 February 1811, his diploma work consisting of a drawing of a reconstruction of the Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel located on a rocky outcrop above the city of Athens and contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historical significance, the most famous being the Parthenon. Th ...

. He only ever exhibited five works at the Academy, the last in 1810.

Smirke's relations with Soane reached a new low after the latter, who had been appointed Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy, heavily criticised Smirke's design for the Covent Garden Opera House in his fourth lecture on 29 January 1810. He said:

The practise of sacrificing everything to one front of a building is to be seen, not only in small houses where economy might in some degree apologize for the absurdity, but it is also apparent in large works of great expense ... And these drawings of a more recent work (here two drawings of Covent Garden theatre were displayed) point out the glaring impropriety of this defect in a manner if possible still more forcible and more subversive of true taste. The public attention, from the largeness of the building, being particularly called to the contemplation of this national edificeTogether with John Nash and Sir John Soane, he became an official architect to the

Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the English royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of Woods, Forests, Land Reven ...

in 1813 (an appointment he held until 1832) at a salary of £500 per annum, thereby reaching the height of the profession. In 1819 he was made surveyor of the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and ...

. In 1819, he married Laura Freston, daughter of The Reverend

The Reverend is an honorific style most often placed before the names of Christian clergy and ministers. There are sometimes differences in the way the style is used in different countries and church traditions. ''The Reverend'' is correctl ...

Anthony Freston, the great-nephew of the architect Matthew Brettingham

Matthew Brettingham (1699 – 19 August 1769), sometimes called Matthew Brettingham the Elder, was an 18th-century Englishman who rose from humble origins to supervise the construction of Holkham Hall, and become one of the country's best-know ...

. The only child of the marriage was a daughter Laura. In 1820, he was made surveyor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of a portfolio of lands, properti ...

, and also in 1820 he became treasurer to the Royal Academy. He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

in 1832, and received the RIBA

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

Royal Gold Medal

The Royal Gold Medal for architecture is awarded annually by the Royal Institute of British Architects on behalf of the British monarch, in recognition of an individual's or group's substantial contribution to international architecture. It is gi ...

for Architecture in 1853. Smirke lived at 81 Charlotte Street, London, commemorated now by a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term ...

on the building. He retired from practice in 1845, after which Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

made him a member of the Commission for London Improvements. In 1859, he resigned from the Royal Academy and retired to Cheltenham

Cheltenham (), also known as Cheltenham Spa, is a spa town and borough on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort, following the discovery of mineral s ...

, where he lived in Montpellier House, Suffolk Square. He died there on 18 April 1867 and was buried in the churchyard of St Peter's in Leckhampton

Leckhampton is a Gloucestershire village and a district in south Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The area is in the civil parish of Leckhampton with Warden Hill and is part of the district of Cheltenham. The population of the civil pari ...

. His estate was worth £90,000.

He is known to have designed or remodelled over twenty churches, more than fifty public buildings and more than sixty private houses. This productivity inspired James Planché

James Robinson Planché (27 February 1796 – 30 May 1880) was a British dramatist, antiquary and officer of arms. Over a period of approximately 60 years he wrote, adapted, or collaborated on 176 plays in a wide range of genres including ...

's 1846 chorus in his burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

of Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

' '' The Birds'':

Go to work, rival SmirkeThe rapid rise of Smirke was due to political patronage.page 79, J. Mordaunt Crook: ''The British Museum A Case-study in Architectural Politics'', 1972, Pelican Books He was a

Make a dash, À la Nash

Something try at, worthy Wyatt

Plans out carry, great asBarry Barry may refer to: People and fictional characters * Barry (name), including lists of people with the given name, nickname or surname, as well as fictional characters with the given name * Dancing Barry, stage name of Barry Richards (born c. 195 ...

Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

at a time when this party was in the ascendant. His friends at the Royal Academy, such as Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence (13 April 1769 – 7 January 1830) was an English portrait painter and the fourth president of the Royal Academy. A child prodigy, he was born in Bristol and began drawing in Devizes, where his father was an innkeeper at t ...

, George Dance, Benjamin West

Benjamin West, (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as '' The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the '' Treaty of Paris'', and '' Benjamin Franklin Drawin ...

and Joseph Farington, were able to introduce him to patrons such as: The 1st Marquess of Abercorn; The 1st Viscount Melville; Sir George Beaumont, 7th Baronet

Sir George Howland Beaumont, 7th Baronet (6 November 1753 – 7 February 1827) was a British art patron and amateur painter. He played a crucial part in the creation of London's National Gallery by making the first bequest of paintings to that ...

; The 4th Earl of Aberdeen; The 3rd Marquess of Hertford; The 3rd Earl Bathurst; John 'Mad Jack' Fuller, and The 2nd Earl of Lonsdale. These politicians

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

and aristocrats

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

ensured his rapid advancement and several were to commission buildings from Smirke themselves. Thomas Leverton Donaldson

Thomas Leverton Donaldson (19 October 1795 – 1 August 1885) was a British architect, notable as a pioneer in architectural education, as a co-founder and President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and a winner of the RIBA Royal Gold ...

described Smirke as able to please "Men whom it was proverbially impossible to please". His patron at Lowther Castle, The 1st Earl of Lonsdale, said he was "ingenious, modest and gentlemanly in his manners".

Style

Classicism

Smirke's first major work, the rebuilt Covent Garden Theatre, was the first Greek Doric building in London.John Summerson

Sir John Newenham Summerson (25 November 1904 – 10 November 1992) was one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century.

Early life

John Summerson was born at Barnstead, Coniscliffe Road, Darlington. His grandfather w ...

described the design as demonstrating "how a plain mass of building could be endowed with a sense of gravity by comparatively simple means". During the early part of his career Smirke was, along with William Wilkins, the leading figure in the Greek Revival in England. At the General Post Office in London in the mid-1820s he was still using the giant order

In classical architecture, a giant order, also known as colossal order, is an order whose columns or pilasters span two (or more) storeys. At the same time, smaller orders may feature in arcades or window and door framings within the storeys tha ...

of columns with a certain restraint, but by the time he came to design the main front of the British Museum, probably not planned until the 1830s, all such moderation was gone and he used it lavishly, wrapping an imposing colonnade around whole facade.

Gothic Revival

Smirke, in the view of

Smirke, in the view of Charles Locke Eastlake

Charles Locke Eastlake (11 March 1836 – 20 November 1906) was a British architect and furniture designer.

His uncle, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake PRA (born in 1793), was a Keeper of the National Gallery, from 1843 to 1847, and from 1855 its f ...

, came third in importance amongst the Gothic Revival architects of his generation, after John Nash and James Wyatt, but criticised his work for its theatrical impracticability. He said that his Eastnor Castle (1808–15), a massive, gloomy building with watch towers and a keep, "might have made a tolerable fort before the invention of gunpowder, but as a residence it was a picturesque mistake".

Constructional innovation

Smirke was a pioneer of using bothconcrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

and cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

. A critic writing in 1828 in the ''Athenaeum'' said "Mr. Smirke, is pre-eminent in construction: in this respect he has not his superior in the United Kingdom". James Fergusson, writing in 1849, said "He was a first class builder architect ... no building of his ever showed a flaw or failing and ... he was often called upon to remedy the defects of his brother artist."

Projects in which he used concrete foundations included the Millbank Penitentiary, the rebuilding of the London Custom House and the British Museum. At the first two he was called in when work overseen by previous architects had proved unstable. The prison at Millbank (1812–21; demolished c. 1890) had been designed by an architect called William Williams, but his plan was then revised by Thomas Hardwick

Thomas Hardwick (1752–1829) was an English architect and a founding member of the Architects' Club in 1791.

Early life and career

Hardwick was born in Brentford, Middlesex the son of a master mason turned architect also named Thomas Hard ...

. The largest prison in Europe, it consisted of a hexagonal central courtyard with an elongated pentagonal courtyard on each outer wall of the central courtyard; the three outer corners of the pentagonal courtyards each had a tower one storey higher than the three floors of the rest of the building. Work had started under Hardwick in late 1812, but when the boundary wall had reached a height of about six feet it began to tilt and crack. After 18 months, with £26,000 spent, Hardwick resigned. Work continued and by February 1816 the first prisoners were admitted, but the building creaked and several windows spontaneously shattered. Smirke and the engineer John Rennie the Elder

John Rennie FRSE FRS (7 June 1761 – 4 October 1821) was a Scottish civil engineer who designed many bridges, canals, docks and warehouses, and a pioneer in the use of structural cast-iron.

Early years

He was born the younger son of James Re ...

were called in, and they recommended demolition of three of the towers and the underpinning of the entire building with concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

foundations: the first known use of this material for foundations in Britain since the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. The work cost £70,000, bringing the total cost of the building to £458,000.

From 1825 to 1827 Smirke rebuilt the centre of the

From 1825 to 1827 Smirke rebuilt the centre of the Custom House

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

in the City of London, following the failure of its foundations. The building had been erected from 1813 to the designs of David Laing. The building is 488 feet long, the central 200 feet being Smirke's work.

He used large cast-iron beams to support the floors of the upper galleries at the British Museum; these had to span 41 feet.

Another area where Smirke was an innovator was in the use of quantity surveyors to rationalise the various eighteenth-century systems of estimating and measuring building work.

Writings

In 1806 he published the first and only volume of an intended series of books ''Specimens of Continental Architecture''. Smirke started to write atreatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Tre ...

on architecture in about 1815 and although he worked on it for about 10 years never completed it. In it he made his admiration for the architecture of ancient Greece

Ancient Greek architecture came from the Greek-speaking people (''Hellenic'' people) whose culture flourished on the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy for a period from about 900 BC unti ...

plain. He described it as "the noblest", "simple, grand, magnificent", "with its other merits it has a kind of primal simplicity". This he contrasted with the Architecture of ancient Rome which he described as "corrupt Roman taste", "An excess of ornament is in all cases a symptom of a vulgar or degenerate taste". Of Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It ...

he described as '"till its despicable remains were almost everywhere superseded by that singular and mysterious compound of styles".

Pupils and family

His pupils includedLewis Vulliamy

Lewis Vulliamy (15 March 1791 – 4 January 1871) was an English architect descended from the Vulliamy family of clockmakers.

Life

Lewis Vulliamy was the son of the clockmaker Benjamin Vulliamy. He was born in Pall Mall, London on 15 March 179 ...

, William Burn

William Burn (20 December 1789 – 15 February 1870) was a Scottish architect. He received major commissions from the age of 20 until his death at 81. He built in many styles and was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial Revival,often referred ...

, Charles Robert Cockerell

Charles Robert Cockerell (27 April 1788 – 17 September 1863) was an English architect, archaeologist, and writer. He studied architecture under Robert Smirke. He went on an extended Grand Tour lasting seven years, mainly spent in Greece. ...

, Henry Jones Underwood, Henry Roberts, and his own brother Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, best known for the circular reading room at the British Museum. Another brother, Edward Smirke, was a lawyer and antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

. Their sister Mary Smirke

Mary Smirke (22 June 1779 – 14 September 1853) was an English artist and translator.

Biography

Smirke was one of the eight children born to the painter and illustrator Robert Smirke and his wife Elizabeth, who died in 1825. Their other child ...

was a noted painter and translator.

London buildings

Royal Mint

The former Royal Mint, Tower Hill (1807–12). The main building was designed by the previous architect to the Mint James Johnson, but the design was modified by Smirke, who oversaw its execution. The long stonefaçade

A façade () (also written facade) is generally the front part or exterior of a building. It is a loan word from the French (), which means ' frontage' or ' face'.

In architecture, the façade of a building is often the most important aspect ...

with a ground floor of

channelled rustication, the two upper floors have a broad pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

containing The Royal Arms supported by six Roman Doric attached columns. The end bays are marked by four Doric pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

s; the Greek Doric frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

and lodges are probably by Smirke. The building contained an apartment for the Deputy Master of the Mint, the Assay Master, and Provost of the Moneyers as well as bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes fro ...

stores and Mint Office.

Covent Garden Theatre

The second incarnation of the Covent Garden Theatre (now the Royal Opera House), built in ten months in 1808–1809. It had a symmetrical facade with a tetrastyle portico in the centre, and was the first building in London to use the Greek Doric order.page 473, John Summerson, ''Architecture in Britain 1530–1830'', 8th Edition 1991, Pelican Books The portico was flanked by four bays, the end bays being marked by pilasters with a statue in a niche between. The three bays on each side of the portico had arches on the ground floor and windows above these and a single carved relief above designed

by

The second incarnation of the Covent Garden Theatre (now the Royal Opera House), built in ten months in 1808–1809. It had a symmetrical facade with a tetrastyle portico in the centre, and was the first building in London to use the Greek Doric order.page 473, John Summerson, ''Architecture in Britain 1530–1830'', 8th Edition 1991, Pelican Books The portico was flanked by four bays, the end bays being marked by pilasters with a statue in a niche between. The three bays on each side of the portico had arches on the ground floor and windows above these and a single carved relief above designed

by John Flaxman

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood's pottery. He spent several ye ...

. The main entrance hall, behind the three doors in the portico, was divided into three aisles by square Doric piers. To the south was the grand staircase, rising between walls, the flight was divided into two sections by a landing, the upper floor had four Ionic columns each side of the staircase that supported a barrel vault over it. The horseshoe-shaped auditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theatres, the number of auditoria (or auditoriums) is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoria can be found in entertainment venues, communit ...

was on five levels, and seated 2,800 people, in addition to those in the many private boxes. The building was destroyed by fire in 1857.

Lansdowne House

Lansdowne House, (1816–19) interiors, notably the sculpture gallery, central part of room has a shallowbarrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

with plain coffering; antae

The Antes, or Antae ( gr, Ἄνται), were an early East Slavic tribal polity of the 6th century CE. They lived on the lower Danube River, in the northwestern Black Sea region (present-day Moldova and central Ukraine), and in the regions ...

mark off the part circular ends of the room.

London Ophthalmic Hospital

Smirke's London Ophthalmic Hospital inMoorfields

Moorfields was an open space, partly in the City of London, lying adjacent to – and outside – its northern wall, near the eponymous Moorgate. It was known for its marshy conditions, the result of the defensive wall acting like a dam, ...

(1821–2) moved in 1898 to a nearby site as Moorfields Eye Hospital.

General Post Office

The General Post Office building in St Martins-le-Grand in the

The General Post Office building in St Martins-le-Grand in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

(1825–29; demolished c. 1912). This was the first purpose built post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional se ...

in England. Its main facade had a central hexastyle Greek Ionic portico with pediment, and two tetrastyle porticoes, without pediments, at each end. The main interior space was the large letter-carriers' room, with an elegant iron gallery and a spiral staircase.

British Museum

The main block and facade of the British Museum, Bloomsbury (1823–46). This is Smirke's largest and best-known building. Having previously designed a temporary gallery for the Parthenon sculptures following their acquisition by the British Museum in 1816, his role as architect to the Office of Works also led Smirke to be invited to redesign the museum in 1821. The core design dates from 1823, and stipulated a building surrounding a large central courtyard (or quadrangle) with a grand south front. Given the limited funds—which were granted by parliament on an annual basis—and the need to retain the Museum throughout the rebuilding programme, the work was divided into phases, and was subject to various changes before its completion over 25 years later. In particular, Smirke was forced to abandon plans for a much grander quadrangle with interior porticoes, while from the early 1840s modified the severity of the original design (such as sculpture deiagned byRichard Westmacott

Sir Richard Westmacott (15 July 17751 September 1856) was a British sculptor.

Life and career

Westmacott studied with his father, also named Richard Westmacott, at his studio in Mount Street, off Grosvenor Square in London before going t ...

). The building is constructed of brick with the visible facades cased in massive slabs of Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building ...

, which is also used for architectural elements and string courses along the sides of the building. The first part to be constructed was the "King's Library" of 1823–1828, which forms the east wing. The north section of the west wing, the "Egyptian Galleries" followed 1825–1834. The north wing, housing the library and reading rooms, was built in 1833–1838. The souther part of the west wing and south front were built in 1842–1846 following the demolition of the Townley Gallery and then of Montague House itself. Following Smirke's retirement in 1846, his brother Sydney Smirke

Sydney Smirke (20 December 1797 – 8 December 1877) was a British architect.

Smirke who was born in London, England as the fifth son of painter Robert Smirke and his wife, Elizabeth Russell. He was the younger brother of Sir Robert Smirke ...

continued to work on the building, adding galleries in the style of the original building, while also building the Round Reading Room in the centre of the quadrangle whose original purpose was superseded. Sydney Smirke also added polychromatic decoration in Greek Revival style to replace the plainer interiors designed by his brother, especially in the entrance hall and sculpture galleries.

The main feature of the south front is the great colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or cur ...

of 44 Greek Ionic columns. The columns are 45 feet high and five feet in diameter; their capitals

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

are loosely based on those of the temple of Athena Polias at Priene

Priene ( grc, Πριήνη, Priēnē; tr, Prien) was an ancient Greek city of Ionia (and member of the Ionian League) located at the base of an escarpment of Mycale, about north of what was then the course of the Maeander River (now called th ...

and the bases on those of the temple of Dionysus at Teos. Many of the mouldings in turn derive from the Erechtheion in Athens, including the main doorway from the colonnade. At the centre of the colonnade is an octastyle portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cul ...

, two columns deep; the colonnade continues for three more columns before embracing the two wings to either side. Beyond the facade Smirke built two smaller wings (the Residences), decorated across the front with Doric pilasters. The Residences originally contained houses for the principal officers of the Museum who were expected to live on site, such as the Principal Librarian ( Director of the museum) and heads of departments (or Keepers). These buildings frame the main building and forecourt without dominating it, while also screening the backs of the buildings in the adjacent streets. The major surviving interiors are the entrance hall with the Great Stair – in the form of an Imperial staircase

An imperial staircase (sometimes erroneously known as a "double staircase") is the name given to a staircase with divided flights. Usually the first flight rises to a half-landing and then divides into two symmetrical flights both rising wit ...

– rising to the west, and the "King's Library". This, built to house 65,000 books, is 300 feet long, 41 feet wide and 31 feet high, the centre section being slightly wider, with four great Aberdeen granite columns with Corinthian capitals carved from Derbyshire alabaster. The only major interior to survive in the north wing is the "Arched Room" at the west end. The "Egyptian Gallery" matches the "King's Library" but is much plainer in decoration.

The Inner Temple

Smirke's works at the Inner Temple included his only Gothic buildings in London. They included thelibrary

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

(1827-8) and the remodelling of the Great Hall in 1819 (which burnt down and was rebuilt by Sydney Smirke in 1868). Nearly all Smirke's work was destroyed in the 1940–1941 London Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

and has been rebuilt to a completely different design, the only major survival being the Paper Buildings of 1838, in a simple classical style.

Former Royal College of Physicians

The

The Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

and Union Club building (1824–27) in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

(now Canada House) The building is much altered, the north front though retains Smirke's hexastyle Ionic portico, and the east front (to Trafalgar Square) still has his portico in antis

An anta (pl. antæ, antae, or antas; Latin, possibly from ''ante'', "before" or "in front of"), or sometimes parastas (pl. parastades), is an architectural term describing the posts or pillars on either side of a doorway or entrance of a Greek ...

. The building is of Bath Stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of ...

. There were several extensions and remodellings during the 20th century.

Lancaster House

Smirke was first involved with the design of Lancaster House in 1825, was dismissed and then brought back in 1832. He added the top floor, and designed the interiors apart from the State Rooms. His involvement ceased in 1840.Somerset House

The east wing of Somerset House, and the adjacent King's (formerly Smirke) Building ofKing's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

, on the Strand (1829–31). The Thames front follows the design of the original architect Sir William Chambers

__NOTOC__

Sir William Chambers (23 February 1723 – 10 March 1796) was a Swedish-Scottish architect, based in London. Among his best-known works are Somerset House, and the pagoda at Kew. Chambers was a founder member of the Royal Academy.

Bio ...

being a mirror image of the west wing, the building stretches back toward the Strand by 25 bays of two and half stories, the centre five bays with giant attached Corinthian columns and end three bays are of three full stories and also the end bays have Corinthian pilasters, and general being plainer than the facades by Chambers.

Carlton Club

Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in St James's, London. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and election only.

History

T ...

(1833–6) was rebuilt 1854–1856 by Sydney Smirke, bombed in 1940 and later demolished.

The Oxford and Cambridge Club

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

. The first floor windows have carved relieves above them, the entrance porch is of a single storey with Corinthian columns. The interiors are in Smirke's usual restrained Greek revival style.

No. 12 Belgrave Square

Belgrave Square

Belgrave Square is a large 19th-century garden square in London. It is the centrepiece of Belgravia, and its architecture resembles the original scheme of property contractor Thomas Cubitt who engaged George Basevi for all of the terraces fo ...

:

Smirke designed No. 12 Belgrave square, built 1830–1833 for John Cust, 1st Earl Brownlow

John Cust, 1st Earl Brownlow, GCH (19 August 1779 – 15 September 1853) was a British Peer and Tory politician.

Life

Cust was the eldest son of the 1st Baron Brownlow and his second wife, Frances. He was educated at Eton (1788–93) ...

.

London churches

For Smirke's London churches see Church Architecture below.Public buildings outside London

Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

, Cumberland County Courts (1810–12), in a Gothic style.

* Appleby Market House (1811).

* Carlisle, The Eden Bridge (1812–15) widened in 1932.

* Whitehaven

Whitehaven is a town and port on the English north west coast and near to the Lake District National Park in Cumbria, England. Historically in Cumberland, it lies by road south-west of Carlisle and to the north of Barrow-in-Furness. It i ...

Fish Market (1813) demolished c. 1852, and Butter Market (1813) demolished 1880.

* Gloucester Shire Hall

Gloucester Shire Hall is a municipal building in Westgate Street, Gloucester. The shire hall, which is the main office and the meeting place of Gloucestershire County Council, is a grade II listed building.

History

The building was designed b ...

(1814–16).

* Gloucester, Westgate Bridge (1814–17)

* Perth Sheriff Court (1815–19)

* Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester, England, Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. ...

Shirehall (1815–17).

* the Wellington Monument, Dublin (Wellington Testimonial), started in 1817 it was only completed in 1861, at it is the largest obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

in Europe.

* Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town, linking it wi ...

County Gaol, (1817–19).

* Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town, linking it wi ...

Sessions House

A sessions house in the United Kingdom was historically a courthouse that served as a dedicated court of quarter sessions, where criminal trials were held four times a year on quarter days. Sessions houses were also used for other purposes to do w ...

(1824) (now known as County Hall).

* Ledbury

Ledbury is a market town and civil parish in the county of Herefordshire, England, lying east of Hereford, and west of the Malvern Hills.

It has a significant number of timber-framed structures, in particular along Church Lane and High Stree ...

St. Katherine's Hospital (1822–25) in a Gothic style.

* Lincoln County Courts and Gaol in Lincoln Castle

Lincoln Castle is a major medieval castle constructed in Lincoln, England, during the late 11th century by William the Conqueror on the site of a pre-existing Roman fortress. The castle is unusual in that it has two mottes. It is one of only ...

(1823–30) both in a Gothic style to harmonise with the castle.

* Salop Infirmary, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, rebuild (1827–30), consulting architect.

* the Gaol St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

(c. 1831).

* Shrewsbury Shire Hall (1834–37) demolished 1971.

Domestic architecture

Brightling Park

Brightling Park (previously known as Rose Hill) is a country estate which lies in the parishes of Brightling and Dallington in the Rother district of East Sussex, England. It is now the home of Grissell Racing, who have operated a racehorse tra ...

west wing, observatory and follies (temple, obelisk) c. 1800–10

* Eywood, Herefordshire, (1806–07) major extension, demolished 1955

* Upleatham Hall, North Riding, Yorkshire (1810) extension, demolished 1897

* Bickley Hall, Kent, (1810) extension of large library wing, demolished 1963

* Cirencester House

Cirencester Park is a country house in the parish of Cirencester in Gloucestershire, England, and is the seat of the Bathurst family, Earls Bathurst. It is a Grade II* listed building. The gardens are Grade I listed on the Register of H ...

north wing (1810–11) and rebuilt east front 1830.

* alterations to Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

from 1816, damaged by fire in 1843 it was reconstructed by Sydney Smirke.

* Armley House, Yorkshire, (1817).

* Whittingehame

Whittingehame is a parish with a small village in East Lothian, Scotland, about halfway between Haddington and Dunbar, and near East Linton. The area is on the slopes of the Lammermuir Hills. Whittingehame Tower dates from the 15th century an ...

House, East Lothian

East Lothian (; sco, East Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Ear) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In 1975, the his ...

(1817–18).

* Haffield House, Donnington, Herefordshire (1817–18).

* Hardwicke Court

Hardwicke Court is a Grade II* listed country house in Hardwicke, Gloucestershire, England. The house is Late Georgian in style. It was designed by Sir Robert Smirke and built in 1816–17, although a canal still remains from the earl ...

, near Gloucester (1817–19).

* Oulton Hall

Oulton Hall in Oulton, West Yorkshire, is a Grade II listed building in England. It was once the home of the Blayds/Calverley family. After a major fire in 1850 the hall was remodelled, but its fortunes declined until it was revived for use a ...

(c. 1822) damaged by fire 1850 and restored by Sydney Smirke

* Normanby Hall (1825–30)

Smirke used the Elizabethan Style

Elizabethan architecture refers to buildings of a certain style constructed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland from 1558–1603. Historically, the era sits between the long era of the dominant architectural style o ...

at:

* Drayton Manor

Drayton Manor, one of Britain's lost houses, was a British stately home at Drayton Bassett, since its formation in the District of Lichfield, Staffordshire, England. In modern administrative areas, it was first put into Tamworth Poor Law Union ...

(1831–35) demolished 1919.

His Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

domestic buildings include:

* Lowther Castle in Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. ...

, (in 1806–11) his first major commission when he was 26.

* Offley Place, Hertfordshire, (1806–10)

* Wilton Castle (Yorkshire) (1810)

* Strathallan Castle, Perthshire, remodelled (1817–18)

* Cholmondeley Castle

Cholmondeley Castle ( ) is a country house in the civil parish of Cholmondeley, Cheshire, England. Together with its adjacent formal gardens, it is surrounded by parkland. The site of the house has been a seat of the Cholmondeley family since ...

(1817–19) a remodelling of the existing building.

* Kinfauns Castle

Kinfauns Castle is a 19th-century castle in the Scottish village of Kinfauns, Perth and Kinross. It is in the Castellated Gothic style, with a slight asymmetry typical of Scottish Georgian. It stands on a raised terrace facing south over the Ri ...

, Perthshire (1822–26)

* Erskine House (1828–45)

A rare use of Norman Revival Architecture Norman Revival architecture is an architectural style

An architectural style is a set of characteristics and features that make a building or other structure notable or historically identifiable. It is a sub-class of style in the visual arts gen ...

is:

* Eastnor Castle

Eastnor Castle, Eastnor, Herefordshire, is a 19th-century mock castle. Eastnor was built for John Cocks, 1st Earl Somers, who employed Robert Smirke, later the main architect of the British Museum. The castle was built between 1811 and 1820. ...

, Ledbury

Ledbury is a market town and civil parish in the county of Herefordshire, England, lying east of Hereford, and west of the Malvern Hills.

It has a significant number of timber-framed structures, in particular along Church Lane and High Stree ...

, Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouths ...

(1812–20)

Church architecture

Commissioners

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissioner has evolved to in ...

on the building of new churches from 1818 onwards, contributing seven himself, six were in the Greek revival style, the exception being the church at Tyldesley that is in the Gothic revival style

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

:

* St Anne's, Wandsworth (1820–22).

* St John's, Chatham, Kent

Chatham ( ) is a town located within the Medway unitary authority in the ceremonial county of Kent, England. The town forms a conurbation with neighbouring towns Gillingham, Rochester, Strood and Rainham.

The town developed around Chatham ...

(1821–22).

* St James, West Hackney (1821–3) bombed during The Blitz in 1940 and 1941 and later demolished.

* St George, Brandon Hill, Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

(1821–23).

* St George, Tyldesley (1821–4).

* St Mary's, Bryanston Square

St Mary's, Bryanston Square, is a Church of England church dedicated to the Virgin Mary on Wyndham Place, Bryanston Square, London. A related Church of England primary school which was founded next to it bears the same name.

History

St Mary's, ...

, London (1821–3).

* St Philip's Church, Salford

St Philip's Church is an Anglican parish church in the diocese of Manchester, in the deanery and archdeaconry of Salford. The church was renamed in 2016 as Saint Philip's Chapel Street. It is located at Wilton Place, off Chapel Street in Salford ...

, Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester is a metropolitan county and combined authority area in North West England, with a population of 2.8 million; comprising ten metropolitan boroughs: Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Stockport, Tam ...

(1822–4); a copy of St Mary's with only minor variations.

Smirke also designed churches for clients other than the commissioners, these included:

* Belgrave Chapel, London 1812, demolished c. 1910.

* St Nicholas Strood, this was a rebuilding in 1812 of a medieval church, the tower of which has been retained, and is in a simplified classical style.

* The Milton Mausoleum at Milton, Nottinghamshire

Milton is a hamlet in Nottinghamshire. It is part of West Markham civil parish, a short distance northwest of West Markham and southwest of Sibthorpe.

Mausoleum

The mausoleum at Milton was designed by Robert Smirke and built in 1831–2. It ...

(1831–32) for Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle.

* The parish church of St. Peter's at Askham, Cumbria

Askham is a village and civil parish in the Eden district of Cumbria, England. It is in the historic county of Westmorland. According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 360, decreasing slightly to 356 at the 2011 Census. It is ...

1832, in a Neo-Norman style.

* The Church of St Peter, Milton Bryan

Milton Bryan is a village and civil parish located in Central Bedfordshire (the spelling Milton Bryant was previously common and is still recognised by postal services). It lies just off the A4012 road, near to its junction with the A5 at Hockl ...

, Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

addition of north transept to church by Lewis Nockalls Cottingham

Lewis Nockalls Cottingham (1787 – 13 October 1847) was a British architect who pioneered the study of Medieval Gothic architecture. He was a restorer and conservator of existing buildings. He set up a Museum of Medieval Art in Waterloo Road, Lon ...

.

Restoration work

Building restoration

Conservation and restoration of immovable cultural property describes the process through which the material, historical, and design integrity of any immovable cultural property are prolonged through carefully planned interventions. The indivi ...

, several commissions coming to him via his post in the Office of Works:

* Gloucester Cathedral