Robert Monckton (died 1722) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Monckton (c. 1659–1722) was an English landowner and Whig politician who sat in the

/ref> He inherited the family estates at about the age of 20.

Unlike his father, who preened himself on his apparently shaky royalist credentials, Robert had

Unlike his father, who preened himself on his apparently shaky royalist credentials, Robert had

/ref>

/ref> His Whig running mate was Sir William Lowther of Swillington, a

Newcastle offered Monckton the borough of Aldborough, where he had recently acquired control by purchase from the Wentworth family, relatives of Lord WentworthThe History of Parliament: Constituencies 1690–1715 – Aldborough

Newcastle offered Monckton the borough of Aldborough, where he had recently acquired control by purchase from the Wentworth family, relatives of Lord WentworthThe History of Parliament: Constituencies 1690–1715 – Aldborough

/ref> The borough had seen bitter contests in the past, as it was aThe History of Parliament: Members 1690–1715 – Arthur Moore

/ref> Monckton accused him of failing to consult the board of trade. He also claimed to have seen a letter referring to an annual 2,000

In 1692, Monckton married Theodosia Fountaine, daughter and co-heir of John Fountaine of Melton on the Hill, near Doncaster, and Hodroyd, near

In 1692, Monckton married Theodosia Fountaine, daughter and co-heir of John Fountaine of Melton on the Hill, near Doncaster, and Hodroyd, near

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

between 1695 and 1713. He took an active part supporting William of Orange in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, and was notable for his involvement in a number of exceptionally bitter and prolonged electoral disputes.

Background and early life

Robert Monckton's father was Sir Philip Monckton, of Cavil, nearHowden

Howden () is a market and minster town and civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It lies in the Vale of York to the north of the M62, on the A614 road about south-east of York and north of Goole, which lies across the Ri ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

. His mother was Anne Eyre, daughter of Robert Eyre of Highlow Hall, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. Robert was the eldest son and had one brother, William, a naval officer, and a sister, Margaret.

Robert Monckton's education seems to have been patchy. On 26 May 1677, aged 17, he entered Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge

Sidney Sussex College (referred to informally as "Sidney") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England. The College was founded in 1596 under the terms of the will of Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex (1531–1589), wife ...

, the college formerly attended by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

, but by 19 Nov. 1678 he was receiving legal training at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn an ...

.The History of Parliament: Members 1690–1715 – Robert Monckton/ref> He inherited the family estates at about the age of 20.

Revolutionary career

Unlike his father, who preened himself on his apparently shaky royalist credentials, Robert had

Unlike his father, who preened himself on his apparently shaky royalist credentials, Robert had Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

associates: he was listed as Low Church in an analysis of the 1705 Parliament. He became a committed opponent of the Duke of York, later James II. He went into exile in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

during the 1680s and was commissioned as an officer by William, Prince of Orange

William, Prince of Orange (Willem Nicolaas Alexander Frederik Karel Hendrik; 4 September 1840 – 11 June 1879), was heir apparent to the Dutch throne as the eldest son of King William III from 17 March 1849 until his death.

Early life

Prince Wi ...

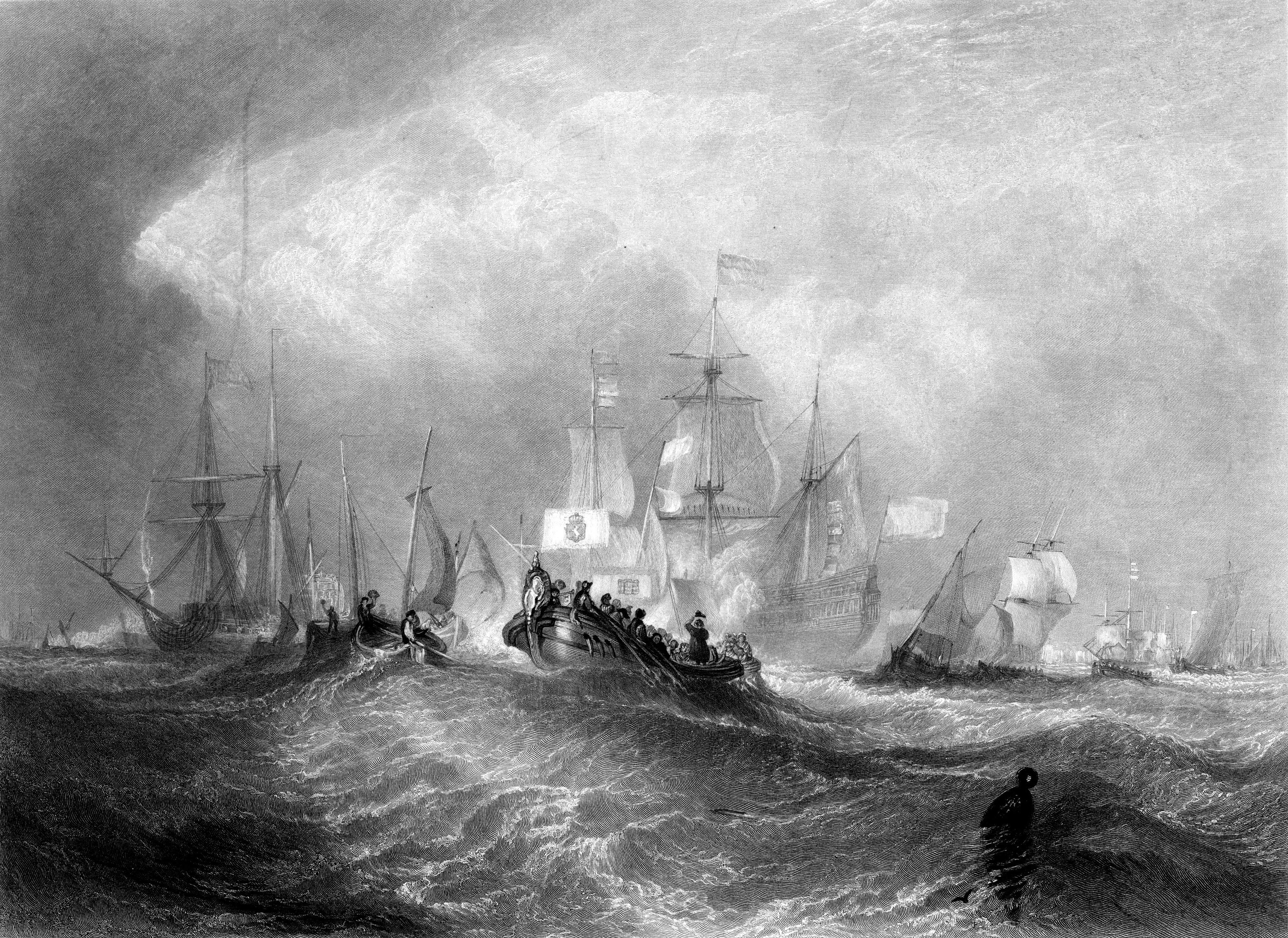

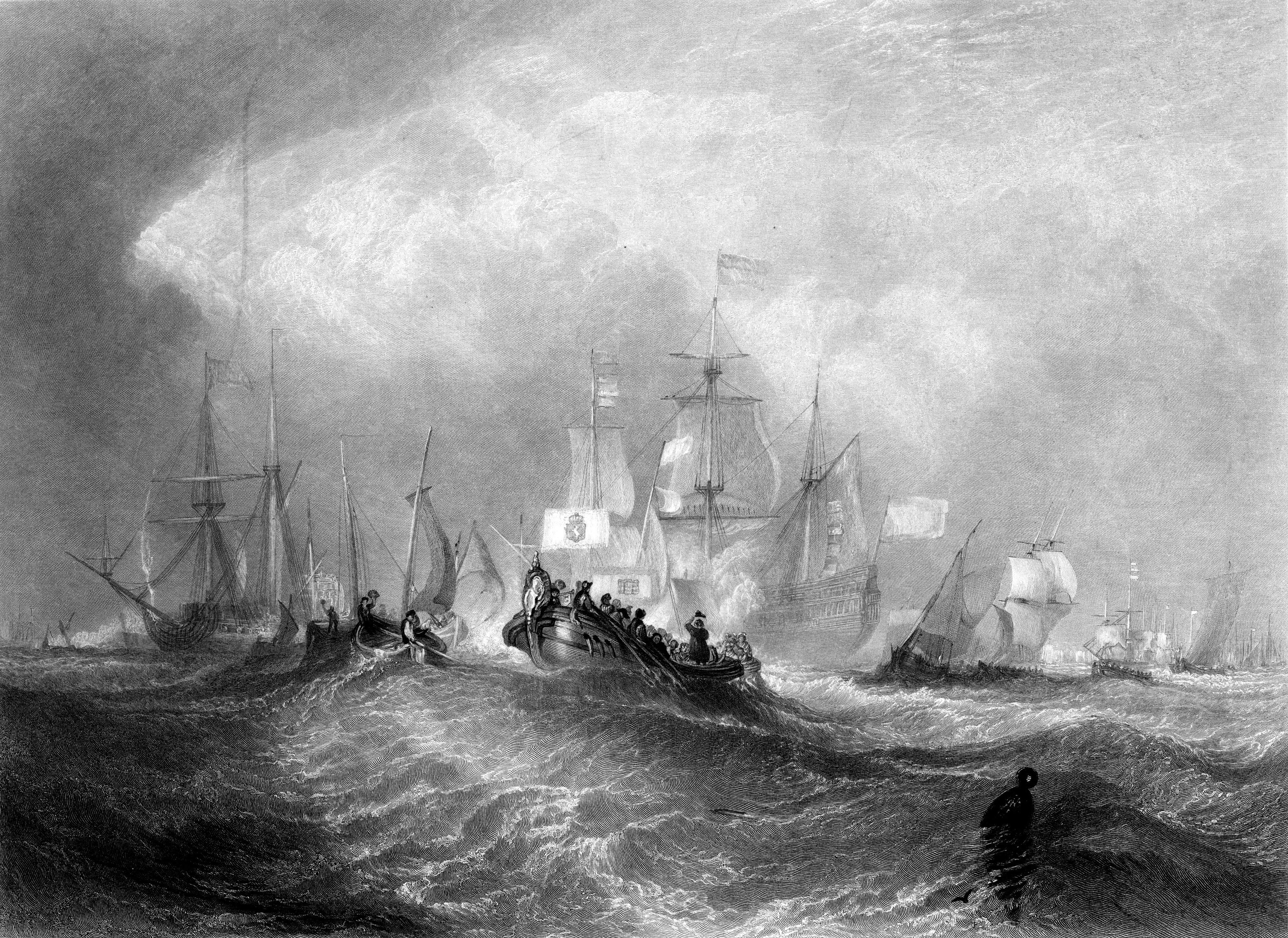

, on 10 November 1688. He took part in the invasion which carried through the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688 and was rewarded with a post as Commissioner for Trade and Plantations.Nottingham University: Biography of Robert Monckton (c. 1659 – 1722) /ref>

Political career

MP for Pontefract

Monckton became a client of the Whig grandeeJohn Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

John Holles, Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Order of the Garter, KG, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, PC (9 January 1662 – 15 July 1711) was an English Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer.

Early life

Holles was born in Edwinstowe, Nottingha ...

. With Newcastle's support, he contested the previously Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

constituency of Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

at the 1695 English general election

The 1695 English general election was the first to be held under the terms of the Triennial Act of 1694, which required parliament to be dissolved and fresh elections called at least every three years. This measure helped to fuel partisan rivalry ...

.The History of Parliament: Constituencies 1690–1715 – Pontefract/ref> His Whig running mate was Sir William Lowther of Swillington, a

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

landowner who was jeered as a "Commonwealthsman" when he plied the electorate with wine. However, Lowther and Monckton had taken the precaution of securing a number of burgage

Burgage is a medieval land term used in Great Britain and Ireland, well established by the 13th century.

A burgage was a town ("borough" or "burgh") rental property (to use modern terms), owned by a king or lord. The property ("burgage tenement ...

votes in the borough and there was actually a sizeable Dissenting community in the town, described by an Anglican clergyman as a "schismatic town." Lowther topped the poll with 80 votes and Monckton came a close second with 78. Sir John Bland, a defeated Tory, petitioned against the election, claiming electoral malpractice by the returning officer

In various parliamentary systems, a returning officer is responsible for overseeing elections in one or more constituencies.

Australia

In Australia a returning officer is an employee of the Australian Electoral Commission or a state electoral c ...

, but the petition failed.

The elections produced a Whig majority in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and William III, who had previously sought to balance Whigs and Tories, now leaned for support on the Whig Junto

The Whig Junto is the name given to a group of leading Whigs who were seen to direct the management of the Whig Party and often the government, during the reigns of William III and Anne. The Whig Junto proper consisted of John Somers, later B ...

– a small elite grouping centred on John Somers

John Somers, 1st Baron Somers, (4 March 1651 – 26 April 1716) was an English Whig jurist and statesman. Somers first came to national attention in the trial of the Seven Bishops where he was on their defence counsel. He published tracts on ...

, later Baron Somers; Charles Montagu, later Earl of Halifax; Thomas Wharton, later Marquess of Wharton and Edward Russell, later Earl of Orford. Monckton was aligned with the Country Whigs, a provincial Member backing the Whig ministry on many measures, but unwilling to countenance the more vindictive policies of the Junto. However, unlike Robert Harley, the most prominent of the Country party, he remained a committed Whig and did not drift toward the Tories.

Monckton was a reliable supporter of the King's economic demands, voting, for example, to fix the guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

at 22 shillings. However he voted against the attainder of Fenwick, the failed and pathetic Jacobite conspirator on 25 November 1696. In February 1697 he was called by the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

as a witness 'to some matters which concern the Earl of Monmouth

Earl of Monmouth was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of England. The title was first created for English courtier Robert Carey, 1st Baron Carey in 1626. He had already been created Baron Carey, of Leppington, in 1622, also in the P ...

.' Monmouth had been Monckton's commanding officer in 1688 and had served as Tory First Lord of the Treasury

The first lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom, and is by convention also the prime minister. This office is not equivalent to the ...

but had since quarrelled with the king. He was accused of complicity in Fenwick's plot and imprisoned but released in March after investigation.

In February 1697 Monckton got into a financial dispute with Richard Vaughan, a blacksmith. Vaughan fetched Thomas Bailey to act as his bailiff

A bailiff (from Middle English baillif, Old French ''baillis'', ''bail'' "custody") is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. Bailiffs are of various kinds and their offi ...

, and together with Bailey and John Brown, broke into Monckton's London house in Vine Street

Vine Street is a street in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California that runs north–south between Franklin Avenue and Melrose Avenue. The intersection with Hollywood Boulevard was once a symbol of Hollywood itself. The famed intersection fell into ...

. Monckton and his family suffered assault and a complaint of breach of Parliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties. ...

was entered. Bailey, Brown and Vaughan were taken into custody by the Serjeant-at-Arms

A serjeant-at-arms, or sergeant-at-arms, is an officer appointed by a deliberative body, usually a legislature, to keep order during its meetings. The word "serjeant" is derived from the Latin ''serviens'', which means "servant". Historically, s ...

. All three men petitioned the House unsuccessfully, and Vaughan was imprisoned in the Gatehouse for three days.

It is not clear whether the dispute was politically motivated, but it certainly did not affect Monckton's independence of judgement. Though a faithful Whig, in April he voted and acted as teller against a supply bill

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Conv ...

for a land tax. He was also enthusiastic about disbanding the army. On the other hand, he took over management of a bill against the corruption of juries

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartial verdict (a finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Juries developed in England durin ...

and chaired a Committee of the Whole

A committee of the whole is a meeting of a legislative or deliberative assembly using procedural rules that are based on those of a committee, except that in this case the committee includes all members of the assembly. As with other (standing) c ...

on the matter, although the bill lapsed in 1698, when fresh elections became due.

In the 1698 English general election

After the conclusion of the 1698 English general election the government led by the Whig Junto believed it had held its ground against the opposition. Over the previous few years, divisions had emerged within the Whig party between the 'court' sup ...

at Pontefract, Lowther played no part, retiring from Parliament for good. A reliable, radical Whig entered the lists: John Bright, formerly John Liddell, grandson and heir of Sir John Bright, 1st Baronet, a veteran of the Parliamentary army in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, whose name he had adopted. Bright and Monckton did not contest the seat on a joint platform. As a result, the Tory Bland topped the poll with 108 votes, while Bright came second with 72, and Monckton a close third with 71. Monckton petitioned against the result, alleging that eight of Bright's voters had no right to vote. Bright counter-petitioned, making essentially the same allegation against Monckton. The investigating committee found in Bright's favour, and put a motion to the House of Commons to declare him elected, but it failed. A motion was put in favour of Monckton but it was rejected without a vote. Hence a fresh election was called. This time Bright beat Monckton by seven votes, but another petition from the burgesses and aldermen

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members them ...

alleged further malpractice, and the case was again referred to committee. However, rumours of an early dissolution of Parliament

The dissolution of a legislative assembly is the mandatory simultaneous resignation of all of its members, in anticipation that a successive legislative assembly will reconvene later with possibly different members. In a democracy, the new assemb ...

were spreading and Monckton hastened to use his alliance with Newcastle to obtain a safer seat.

MP for Aldborough

Newcastle offered Monckton the borough of Aldborough, where he had recently acquired control by purchase from the Wentworth family, relatives of Lord WentworthThe History of Parliament: Constituencies 1690–1715 – Aldborough

Newcastle offered Monckton the borough of Aldborough, where he had recently acquired control by purchase from the Wentworth family, relatives of Lord WentworthThe History of Parliament: Constituencies 1690–1715 – Aldborough/ref> The borough had seen bitter contests in the past, as it was a

scot and lot

Scot and lot is a phrase common in the records of English, Welsh and Irish medieval boroughs, referring to local rights and obligations.

The term ''scot'' comes from the Old English word ''sceat'', an ordinary coin in Anglo-Saxon times, equivalen ...

borough, with a wide franchise

Franchise may refer to:

Business and law

* Franchising, a business method that involves licensing of trademarks and methods of doing business to franchisees

* Franchise, a privilege to operate a type of business such as a cable television p ...

, though a small electorate. As a result of Newcastle's influence, Monckton was returned as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

unopposed in January 1701, along with Cyril Arthington, who had contested the seat unsuccessfully in the past and had the support of another local landowner.

The parliament had a Tory majority and the Junto soon found themselves accused of treason. The first move to redefine party loyalties came in February with a motion to urge the King to recognise the Duke of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertians ...

, Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

's grandson, as 'King of Spain'. This was a direct attack on the foreign policy of William himself and the previous administration. Monckton denounced this fiercely, saying that "if this vote was carried, he should expect that the next vote would be for owning the pretended Prince of Wales" - a reference to the James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart (10 June 16881 January 1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender by Whigs, was the son of King James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland, and his second wife, Mary of Modena. He was Prince of Wales from ...

, the "Old Pretender", the Jacobite candidate for the throne supported by Louis XIV. He demanded support for England and its allies in what would soon become the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, saying that "he, for one, would be prepared to eat only roots for the good of his country."

In April came moves to remove the Junto members Somers, Halifax and Orford, together with Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, from the king's council. Having rejected their extreme measures in the past, Monckton felt obliged to defend them against a pending impeachment. When the motion came up for debate, Monckton proposed an amendment that the House "would support the King in preventing the union of France and Spain and in the maintaining of the trade and commerce of this kingdom." This irrelevant and unpalatable amendment led to heated debate, with Monckton predicting dire commercial consequences for the present policies. Harley, now Speaker, rose and removed his hat, a gesture intended to silence Monckton, but he continued his diatribe, even when called to order.

Parliament was dissolved later the same year and for the second election of 1701 Monckton reassured Newcastle of his Whig loyalties by promising that he would support other Whig candidates in Yorkshire. He and Arthington were returned again, but in a contested election, with another Newcastle client, William Jessop, a close third. At the 1702 English general election

The 1702 English general election was the first to be held during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain, Queen Anne, and was necessitated by the demise of William III of England, William III. The new government dominated by the Tories (Britis ...

, Monckton was elected unopposed alongside Jessop, as Arthington's patron sold his interest to Newcastle.

Monckton and Jessop were returned together unopposed at the 1705 English general election

The 1705 English general election saw contests in 110 constituencies in England and Wales, roughly 41% of the total. The election was fiercely fought, with mob violence and cries of " Church in Danger" occurring in several boroughs. During the pr ...

. Monckton never again attained the prominence that marked the first years of the century. He became more and more an agent of Newcastle, acting as go-between in his dealings with Harley, whom he warned against being manipulated by the Tories. He was appointed to the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

in 1707, a post which allowed him to develop his interest in commerce. He was returned again with Jessopp at the 1708 British general election

The 1708 British general election was the first general election to be held after the Acts of Union had united the Parliaments of England and Scotland.

The election saw the Whigs finally gain a majority in the House of Commons, and by November ...

and generally supported distinctively Whig measures, although he found the venality of the party hard to bear at times. In 1710 he was reported as saying "he'll be no Whig any longer, for he says he angered since he came to town some of his old friends by being so reasonable as to maintain 'twas fit the Queen should use her pleasure in disposing employments as she pleases." However, this was clearly a figure of speech, as he was returned unopposed with Jessop again as a Whig at the 1710 British general election

The 1710 British general election produced a landslide victory for the Tories. The election came in the wake of the prosecution of Henry Sacheverell, which had led to the collapse of the previous government led by Godolphin and the Whig Junto.

...

. He was in favour of the Hanoverian Succession

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

, during the 1710–1711 session.

In 1711, Newcastle died. He was succeeded by his nephew Thomas Pelham-Holles

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne, (21 July 169317 November 1768) was a British Whig statesman who served as the 4th and 6th Prime Minister of Great Britain, his official life extended ...

. Monckton attempted to intercede in property disputes between the new duke and the dowager duchess, but only alienated both parties. As a result, the duchess announced that she would not support him at Aldborough, although Pelham was publicly undecided. Monckton continued his personal friendship with Harley, now Lord Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

and head of a Tory ministry, while still voting with the Whigs on most issues. However Monckton voted against the party line over a 1713 commercial treaty with France, finally losing himself his safe seat. At the 1713 British general election

The 1713 British general election produced further gains for the governing Tory party. Since 1710 Robert Harley had led a government appointed after the downfall of the Whig Junto, attempting to pursue a moderate and non-controversial policy, b ...

, he was not a candidate at Aldborough but tried his luck again at Pontefract. He came fourth and last in the poll, with two Tories elected.

Even this did not end Monckton's involvement in politics. For another year he continued to give evidence before the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

, particularly in regard to the activities of Arthur Moore. Moore was a protégé of Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (; 16 September 1678 – 12 December 1751) was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tories, and supported the Church of England politically des ...

who had been involved in trade negotiations with Spain. Moore was accused of making personal profit from this work, in particular annexing a substantial part of the ''asiento de negros

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Afri ...

'', the Spanish concession of supplying slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

to the Spain's colonies in the Americas./ref> Monckton accused him of failing to consult the board of trade. He also claimed to have seen a letter referring to an annual 2,000

louis d'or

The Louis d'or () is any number of French coins first introduced by Louis XIII in 1640. The name derives from the depiction of the portrait of King Louis on one side of the coin; the French royal coat of arms is on the reverse. The coin was re ...

bribe that Moore had been promised. It seems that Monckton's attack was made in concert with a group of Whig leaders, including Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

. However, it was also rumoured that his contribution was also part of a Tory internecine feud, favouring Harley against Bolingbroke.

The queen died in August 1714, and with a new reign, a new dynasty and a new session of parliament, Monckton retired to his Yorkshire estates. He died in 1722 and was buried on 13 November.

Marriage and Family

In 1692, Monckton married Theodosia Fountaine, daughter and co-heir of John Fountaine of Melton on the Hill, near Doncaster, and Hodroyd, near

In 1692, Monckton married Theodosia Fountaine, daughter and co-heir of John Fountaine of Melton on the Hill, near Doncaster, and Hodroyd, near Barnsley

Barnsley () is a market town in South Yorkshire, England. As the main settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley and the fourth largest settlement in South Yorkshire. In Barnsley, the population was 96,888 while the wider Borough has ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

. They had a number of children. Robert's heir was John Monckton, later to become the 1st Viscount Galway. He was a very successful Whig politician and a more pliable client of the Pelhams than Robert had proved.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Monckton, Robert 1650s births 1722 deaths English MPs 1695–1698 English MPs 1701 English MPs 1701–1702 English MPs 1702–1705 English MPs 1705–1707 British MPs 1707–1708 British MPs 1708–1710 British MPs 1710–1713 Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies Whig (British political party) MPs Alumni of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge