Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (24 May 1852 – 20 March 1936) was a Scottish politician, writer, journalist and adventurer. He was a

Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (24 May 1852 – 20 March 1936) was a Scottish politician, writer, journalist and adventurer. He was a

Although a socialist, in the 1886 general election he stood as a

Although a socialist, in the 1886 general election he stood as a

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

Member of Parliament (MP); the first ever socialist member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

; a founder, and the first president, of the Scottish Labour Party

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

; a founder of the National Party of Scotland

The National Party of Scotland (NPS) was a centre-left political party in Scotland which was one of the predecessors of the current Scottish National Party (SNP). The NPS was the first Scottish nationalist political party, and the first which c ...

in 1928; and the first president of the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from ...

in 1934.

Youth

Cunninghame Graham was the eldest son of Major William Bontine of the Renfrew Militia and formerly aCornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

in the Scots Greys

The Royal Scots Greys was a Cavalry regiments of the British Army, cavalry regiment of the British Army from 1707 until 1971, when they amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards) to form the Royal Scots Dragoon Guard ...

with whom he served in Ireland. His mother was the Hon. Anne Elizabeth Elphinstone-Fleeming, daughter of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Charles Elphinstone-Fleeming

Admiral Hon. Charles Elphinstone Fleeming (18 June 1774 – 30 October 1840) was a British officer of the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He commanded a succession of smaller vessels during the ear ...

of Cumbernauld and a Spanish noblewoman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

, Doña Catalina Paulina Alessandro de Jiménez, who reputedly, along with her second husband, Admiral James Katon, heavily influenced Cunninghame Graham's upbringing. Thus the first language Cunninghame Graham learned was his mother's maternal tongue, Spanish. He spent most of his childhood on the family estate of Finlaystone

Finlaystone House is a mansion and estate in the Inverclyde council area and historic county of Renfrewshire. It lies near the southern bank of the Firth of Clyde, beside the village of Langbank, in the west central Lowlands of Scotland.

Finl ...

in Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Renfr ...

and Ardoch in Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders P ...

, Scotland, with his younger brothers Charles and Malise.

After being educated at Harrow public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

in England, Robert finished his education in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, before moving to Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

to make his fortune cattle ranch

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are most often ...

ing. He became known as a great adventurer and gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia. Gauchos became greatly admired and ...

there, and was affectionately known as Don Roberto. He also travelled in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

disguised as a Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

to find the "forbidden" city of Taroudant but was captured by a Caid (Si Taieb ben Si Ahmed El Hassan El Kintafi), prospected for gold in Spain, befriended Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, Bison hunting, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa, Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but ...

in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, and taught fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...

in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

, having travelled there by wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings. It ...

from San Antonio de Bexar

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

with his young bride ''sic'' "Gabrielle Marie de la Balmondiere" a supposed half-French, half-Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

an poet.

Convert to socialism

After the death of his father in 1883 he reverted to the Cunninghame Graham surname. He returned to the UK and became interested in politics. He attended socialist meetings where he heard and metWilliam Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, H. M. Hyndman

Henry Mayers Hyndman (; 7 March 1842 – 20 November 1921) was an English writer, politician and socialist.

Originally a conservative, he was converted to socialism by Karl Marx's '' Communist Manifesto'' and launched Britain's first left-wing ...

, Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

and John Burns

John Elliot Burns (20 October 1858 – 24 January 1943) was an English trade unionist and politician, particularly associated with London politics and Battersea. He was a socialist and then a Liberal Member of Parliament and Minister. He was ...

. Despite his wealthy origins, Graham was converted to socialism and he began to speak at public meetings. He was an impressive orator and was especially good at dealing with hecklers.

Liberal Party MP

Although a socialist, in the 1886 general election he stood as a

Although a socialist, in the 1886 general election he stood as a Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

candidate at North West Lanarkshire. His election programme was extremely radical and called for:

*the abolition of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

*universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

*the nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of land, mines and other industries

*free school meals

*disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular stat ...

of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

*Scottish Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

*the establishment of an eight-hour working day

Supported by liberals and socialists, Graham defeated the Unionist candidate by 322 votes. He had stood against the same candidate at the 1885 general election, in which he was defeated by over 1100 votes.

Robert Cunninghame Graham refused to accept the conventions of the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

. On 12 September 1887 he was suspended from parliament for making what was called a "disrespectful reference" to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

. He was the first MP ever to be suspended from the House of Commons for swearing

Profanity, also known as cursing, cussing, swearing, bad language, foul language, obscenities, expletives or vulgarism, is a socially offensive use of language. Accordingly, profanity is language use that is sometimes deemed impolite, rud ...

; the word was damn

Damnation (from Latin '' damnatio'') is the concept of divine punishment and torment in an afterlife for actions that were committed, or in some cases, not committed on Earth.

In Ancient Egyptian religious tradition, citizens would recite th ...

.

Graham's main concerns in the House of Commons were the plight of the unemployed and the preservation of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

. He complained about attempts in 1886 and 1887 by the police to prevent public meetings and free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been ...

. He attended the protest demonstration in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

on 13 November 1887 that was broken up by the police and became known as Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

. Graham was badly beaten during his arrest and taken to Bow Street Police Station, where his uncle, Col William Hope VC, attempted to post bail. Both Cunninghame Graham, who was defended by H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, and John Burns

John Elliot Burns (20 October 1858 – 24 January 1943) was an English trade unionist and politician, particularly associated with London politics and Battersea. He was a socialist and then a Liberal Member of Parliament and Minister. He was ...

were found guilty for their involvement in the demonstration and sentenced to six weeks imprisonment.

When Graham was released from Pentonville prison

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury ar ...

he continued his campaign to improve the rights of working people and to curb their economic exploitation. He was suspended from the House of Commons in December 1888 for protesting about the working conditions of chain makers. His response to the Speaker of the House, "I never withdraw", was later used by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

in ''Arms and the Man''.

Scottish independence and the Scottish Labour Party

Graham was a strong supporter ofScottish independence

Scottish independence ( gd, Neo-eisimeileachd na h-Alba; sco, Scots unthirldom) is the idea of Scotland as a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom, and refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

S ...

. In 1886, he helped establish the Scottish Home Rule Association (SHRA), and while in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, he made several attempts to persuade fellow MPs of the desirability of a Scottish parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyro ...

. On one occasion, Graham joked that he wanted a "national parliament with the pleasure of knowing that the taxes were wasted in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

instead of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

."

In 1888, Graham attended the SHRA Conference at the Anderton's Hotel in Fleet Street and passed a motion "That in the opinion of this Conference the interests of Scotland demand the establishment of a Scotch national Parliament and an Executive Government having control over exclusively Scotch affairs, with a due regard to the integrity of the Empire". The motion was supported by Mr Cuninghame Graham (as name spelt in article), who said he "wanted a Scotch Parliament to do justice to their crofters and keep them at home, to pass an Eight Hours' Bill for their miners, to settle the liquor laws, and to nationalise the land." Peter Esslemont

Peter Esslemont (13 June 1834 – 8 August 1894) was a Scottish Liberal politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1885 to 1892.

Life

Esslemont was born in Balnakettle, Udny, Aberdeenshire the son of Peter Esslemont, a farmer, and his wif ...

MP attended. Dr G.B Clark Chaired conference MP for Caithness-shire.

While in the House of Commons, Graham became increasingly more radical and went on to found the Scottish Labour Party

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

with Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

. Graham left the Liberal Party in 1892 to contest the general election in a new constituency as a Labour candidate.

He supported workers in their industrial disputes and was involved with Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

and the Matchgirls Strike and the 1889 Dockers' Strike. In July 1889, he attended the Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

Congress of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

with James Keir Hardie, William Morris, Eleanor Marx

Jenny Julia Eleanor Marx (16 January 1855 – 31 March 1898), sometimes called Eleanor Aveling and known to her family as Tussy, was the English-born youngest daughter of Karl Marx. She was herself a socialist activist who sometimes worked as a ...

and Edward Aveling

Edward Bibbins Aveling (29 November 1849 – 2 August 1898) was an English comparative anatomist and popular spokesman for Darwinian evolution, atheism and socialism. He was also a playwright and actor.

Aveling was the author of numerous ...

. The following year he made a speech in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

that was considered by the authorities to be so revolutionary that he was arrested and expelled from France.

Graham was a supporter of the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

and made several attempts to introduce a Bill on the subject. He made some progress with this in the summer of 1892, but he was unable to persuade the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

government, headed by Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, to allocate time for the Bill to be fully debated.

At the 1892 general election Graham stood as the Scottish Labour Party candidate for Glasgow Camlachie. He was defeated, bringing his parliamentary career to an end. He remained active in political circles, though, helping his colleague Keir Hardie establish the Independent Labour Party and enter parliament as the MP for West Ham

West Ham is an area in East London, located east of Charing Cross in the west of the modern London Borough of Newham.

The area, which lies immediately to the north of the River Thames and east of the River Lea, was originally an ancien ...

. However, he became disillusioned by the pettiness and dissent of those he called "piss-pot socialists" and increasingly turned to a nascent Scottish nationalism

Scottish nationalism promotes the idea that the Scottish people form a cohesive nation and national identity.

Scottish nationalism began to shape from 1853 with the National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights, progressing into t ...

as a means of achieving social justice and cultural revival.

Graham retained a strong belief in Scottish home rule. He played an active part in the establishment of the National Party of Scotland

The National Party of Scotland (NPS) was a centre-left political party in Scotland which was one of the predecessors of the current Scottish National Party (SNP). The NPS was the first Scottish nationalist political party, and the first which c ...

(NPS) in 1928 and was elected the Honorary President of the new Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from ...

in 1934. He was several times the Glasgow University Scottish Nationalist Association

The Glasgow University Scottish Nationalist Association (GUSNA) is a student organisation formed in 1927 at the University of Glasgow which supports Scottish independence.

History

GUSNA is important historically as it predated many pro-independ ...

candidate for the Lord Rectorship of the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, which he lost by only sixty-six votes in 1928 to Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

at the time. This event was pivotal in the founding of the National Party, and the eventual creation of the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from ...

in the 1930s.

Because of his Scottish nationalism, and criticism of what he saw as the Labour Party's timidity and lack of socialist zeal, Graham has been effectively written out of Labour Party history, and the belief has been circulated that after his electoral defeat in 1892, he retired from politics until the late 1920s. This is entirely incorrect; in fact, between 1905 and 1914, Graham, while retaining the position of elder statesman, social commentator, and renowned world-traveller, became more militant, involving himself in many left-wing causes and protests. There is evidence to suggest that he joined the hard-left British Socialist Party, and he was an associate of anarchists and a political assassin. Graham was also a vociferous anti-imperialist at the height of British jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

as well as a high-profile supporter of the women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement and Home Rule for Ireland and India.

Author

Between 1888 and 1892, Graham was a prolific contributor to small-circulation socialist journals, but his literary career took off when he was recruited byFrank Harris

Frank Harris (14 February 1855 – 26 August 1931) was an Irish-American editor, novelist, short story writer, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day.

Born in Ireland, he emigrated to the United State ...

to write for the '' Saturday Review'' in 1895, and he continued writing for the ''Saturday'' until 1926, as well as other journals. His main form was the 'sketch', or sketch-tale', mostly descriptive, atmospheric works on South America and Scotland, which gave his work a unique aesthetic, which carried a subtext of anti-colonialism, nostalgia, and loss. T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

(of Arabia) described his Scottish sketches as "the rain-in-the-air-and-on-the-roof mournfulness of Scotch music in his time-past style . .snap-shots - the best verbal snapshots ever taken I believe." His many works were collected into anthologies. Subject matter included history, biography, poetry, essays, politics, travel and seventeen collections of short stories or literary sketches. Titles include ''Father Archangel of Scotland'' (1896 in conjunction with his wife Gabriela), ''Thirteen Stories'' (1900), ''Success'' (1902), ''Hope'' (1910), ''Scottish Stories'' (1914), ''Brought Forward'' (1916) and ''Mirages'' (1936). Biographies included: ''Hernando de Soto'' (1903), ''Doughty Deeds'' (1925), a biography of his great-great-grandfather, Robert Graham of Gartmore

Robert Graham (1735 – 11 December 1797), who took the name Bontine in 1770 and Cunninghame Graham in 1796, was a Scotland, Scottish politician and poet.

and Portrait of a Dictator (1933). His great-niece and biographer, Jean, Lady Polwarth, published a collection of his short stories (or sketches) entitled ''Beattock for Moffatt and the Best of Cunninghame Graham'' (1979) and Alexander Maitland added his selection under the title ''Tales of Horsemen'' (1981). Professor John Walker published collections of Cunninghame Graham's South American Sketches (1978), Scottish Sketches (1982) and North American Sketches (1986) and Kennedy & Boyd republished the stories and sketches in five volumes (2011 - 2012). In 1988 The Century Travellers reprinted his ''Mogreb-el-Acksa'' (1898) and ''A Vanished Arcadia'' (1901). The former was the inspiration for George Bernard Shaw's play ''Captain Brassbound's Conversion

''Captain Brassbound's Conversion'' (1900) is a play by G. Bernard Shaw. It was published in Shaw's 1901 collection '' Three Plays for Puritans'' (together with '' Caesar and Cleopatra'' and '' The Devil's Disciple''). The first American product ...

''. The latter helped inspire the award-winning film '' The Mission''. More recently The Long Riders Guild Press have reprinted his equestrian travel works in their Cunninghame Graham Collection.

He helped his close friend Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

, whom he had introduced to his publisher Edward Garnett

Edward William Garnett (5 January 1868 – 19 February 1937) was an English writer, critic and literary editor, who was instrumental in the publication of D. H. Lawrence's ''Sons and Lovers''.

Early life and family

Edward Garnett was born i ...

at Duckworth Duckworth may refer to:

* Duckworth (surname), people with the surname ''Duckworth''

* Duckworth (''DuckTales''), fictional butler from the television series ''DuckTales''

* Duckworth Books, a British publishing house

* , a frigate

* Duckworth, W ...

, with research for ''Nostromo

''Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard'' is a 1904 novel by Joseph Conrad, set in the fictitious South American republic of "Costaguana". It was originally published serially in monthly instalments of '' T.P.'s Weekly''.

In 1998, the Modern Libra ...

''. Other literary friends included Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford (né Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer ( ); 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals ''The English Review'' and ''The Transatlantic Review'' were instrumental in ...

, John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy (; 14 August 1867 – 31 January 1933) was an English novelist and playwright. Notable works include ''The Forsyte Saga'' (1906–1921) and its sequels, ''A Modern Comedy'' and ''End of the Chapter''. He won the Nobel Prize i ...

, W. H. Hudson

William Henry Hudson (4 August 1841 – 18 August 1922) – known in Argentina as Guillermo Enrique Hudson – was an English Argentines, Anglo-Argentine author, natural history, naturalist and ornithology, ornithologist.

Life

Hudson was the ...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

(who openly admits his debt to Graham for "Captain Brassbound's Conversion

''Captain Brassbound's Conversion'' (1900) is a play by G. Bernard Shaw. It was published in Shaw's 1901 collection '' Three Plays for Puritans'' (together with '' Caesar and Cleopatra'' and '' The Devil's Disciple''). The first American product ...

" as well as a key line in ''Arms and the Man

''Arms and the Man'' is a comedy by George Bernard Shaw, whose title comes from the opening words of Virgil's ''Aeneid'', in Latin:

''Arma virumque cano'' ("Of arms and the man I sing").

The play was first produced on 21 April 1894 at the Aven ...

'') and G. K. Chesterton, who proclaimed him "The Prince of Preface Writers" and famously declared in his autobiography that while Cunninghame Graham would never be allowed to be Prime Minister, he instead "achieved the adventure of being Cunninghame Graham", which Shaw described as "an achievement so fantastic that it would never be believed in a romance."

There is a seat dedicated to Cunninghame Graham in the Scottish Storytelling Centre

The Scottish Storytelling Centre, the world's first purpose-built modern centre for live storytelling, is located on the High Street in Edinburgh's Royal Mile, Scotland, United Kingdom. It was formally opened on 1 June 2006 by Patricia Fergus ...

in Edinburgh with the inscription:

"R B 'Don Roberto' Cunninghame Graham of Gartmore and Ardoch, 1852–1936, A great storyteller".

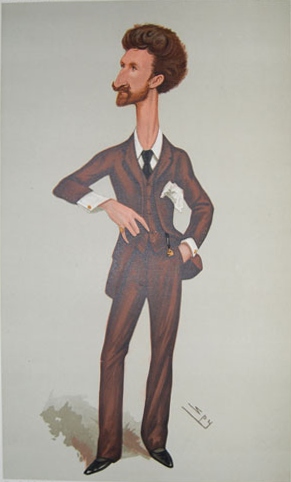

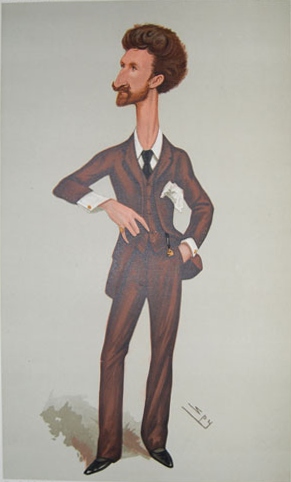

Cunninghame Graham in art

Cunninghame Graham was a staunch supporter of the artists of his day and a popular subject. He sat for artists such as SirWilliam Rothenstein

Sir William Rothenstein (29 January 1872 – 14 February 1945) was an English painter, printmaker, draughtsman, lecturer, and writer on art. Emerging during the early 1890s, Rothenstein continued to make art right up until his death. Though he c ...

, who painted Don Roberto as ''The Fencer''; Sir John Lavery

Sir John Lavery (20 March 1856 – 10 January 1941) was a Northern Irish painter best known for his portraits and wartime depictions.

Life and career

John Lavery was born in inner North Belfast, baptised at St Patrick's Church, Belfast a ...

, whose famous ''Don Roberto: Commander for the King of Aragon in the Two Sicilies'' was on the cover of the Penguin Books

Penguin Books is a British publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers The Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the following year.G. P. Jacomb-Hood, who painted his official portrait on entering parliament, with whom, along with Whistler, he was personal friends.

Guide to the Anne Elizabeth Bontine Diaries and Other Materials.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Biographical Profile

at ''ElectricScotland.com''

Rare Reprints – Cunninghame Graham

* *

R. B. Cunninghame Graham, Rauner Special Collection, Dartmouth College Library, N.H.Canning House Special Collection – R. B. Cunninghame Graham

* ttp://www.horsetravelbooks.com/rbcg.htm The Cunninghame Graham Collection* *

First Foot – Cunninghame-GrahamNational Portrait GalleryCross party support to honour Scottish Hero Robert Cunninghame Graham

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cunninghame Graham, Robert 1852 births 1936 deaths Anglo-Scots Writers from London People educated at Harrow School Presidents of the Scottish National Party Scottish journalists Scottish explorers Scottish nationalists Scottish travel writers 20th-century Scottish historians Scottish biographers Scottish essayists Scottish socialists Scottish Liberal Party MPs Scottish translators Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Scottish constituencies UK MPs 1886–1892 Deaths from pneumonia in Argentina Scottish Labour Party (1888) politicians British political party founders 19th-century Scottish historians

George Washington Lambert

George Washington Thomas Lambert (13 September 1873 – 29 May 1930) was an Australian artist, known principally for portrait painting and as a war artist during the First World War.

Early life

Lambert was born in St Petersburg, Russia, th ...

painted him in oil with his horse Pinto and James McBey

James McBey (23 December 1883 – 1 December 1959) was a largely self-taught artist and etcher whose prints were highly valued during the later stages of the etching revival in the early 20th century. He was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Lett ...

portrayed him in old age. There are also busts by Weiss and Jacob Epstein

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American-British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1911.

He often produc ...

. The Dumbarton born artist, William Strang

William Strang (13 February 1859 – 12 April 1921) was a Scottish painter and printmaker, notable for illustrating the works of Bunyan, Coleridge and Kipling.

Early life

Strang was born at Dumbarton, the son of Peter Strang, a builder, an ...

, used Cunninghame Graham as the model for his series of etchings of Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of Wester ...

. It is unsurprising that he was at the mercy of cartoonists such as Tom Merry

Tom Merry is the principal character in the "St Jim's" stories which appeared in the boy's weekly paper, ''The Gem'', from 1907 to 1939. The stories were all written using the pen-name of Martin Clifford, the majority by Charles Hamilton who wa ...

, who portrayed him in prison garb, and caricaturists such as Max and Spy

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

.

Final years

Robert Cunninghame Graham remained sprightly and rode daily even in his eighties. He continued to write, and held the office of President of the Scottish Branch of the P.E.N. Club, and involve himself in politics. He died from pneumonia on 20 March 1936 at the Plaza Hotel inBuenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, following a visit to the birthplace of his friend William Hudson. He lay in state in the Casa del Teatro and received a countrywide tribute led by the President of the Republic before his body was shipped home to be buried beside his wife on 18 April 1936, in the ruined Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

Priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of mon ...

on the island of Inchmahome

Inchmahome, an anglicisation of Innis Mo Cholmaig ("my-Colmac's island"), is the largest of three islands in the Lake of Menteith, in Stirlingshire.

History

Inchmahome is best known as the location of Inchmahome Priory and for the attendant p ...

, Lake of Menteith

Lake of Menteith, also known as Loch Inchmahome (Scottish Gaelic: ''Loch Innis Mo Cholmaig''), is a loch in Scotland located on the Carse of Stirling (the flood plain of the upper reaches of the rivers Forth and Teith, upstream from Stirling).

...

, Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

. The following year, June 1937, a monument, the Cunninghame Graham Memorial, was unveiled at Castlehill, Dumbarton, near the family home at Ardoch. Despite the monument being removed to Gartmore

Gartmore (Scottish Gaelic ''An Gart Mòr'') is a village in the Stirling council area, Scotland. It is a village with a view of the Wallace Monument in Stirling, almost 25 miles away.

Formerly in Perthshire, it is one mile from the A81 Glasgo ...

in 1981, closer to the principal Graham estate, which he had been forced to sell in 1901 to the shipping magnate and founder of the Clan Line

The Clan Line was a passenger and cargo shipping company that operated in one incarnation or another from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century.

History Foundation and early years

The company that would become the Clan Lin ...

, Sir Charles Cayzer, Bt, the Cunninghame Graham Memorial Park (which is managed by the National Trust for Scotland

The National Trust for Scotland for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, commonly known as the National Trust for Scotland ( gd, Urras Nàiseanta na h-Alba), is a Scottish conservation organisation. It is the largest membership organ ...

) is still affectionately locally known as "the Mony". His estates at Ardoch and feudal barony of Gartmore passed to his nephew, Captain (later Admiral Sir) Angus Cunninghame Graham

Admiral Sir Angus Edward Malise Bontine Cunninghame Graham of Gartmore and Ardoch (16 February 1893 – 14 February 1981) was a Royal Navy officer who became Flag Officer, Scotland.

Naval career

Educated at Ascham St. Vincent's School, Cunnin ...

, the only son of his brother Cdr. Charles Elphinstone-Fleeming Cunninghame Graham, MVO.

Bibliography

* Notes on the district of Menteith: for tourists and others (1895) * Father Archangel of Scotland and other essays (1896) * Mogreb-el-Acksa: A Journey in Morocco (1898) * Aurora La Cujiñi: A Realistic Sketch in Seville (1898) * The Ipané (1899) * Thirteen Stories (1900) * A Vanished Arcadia: Being Some Account of the Jesuits in Paraguay, 1607 to 1767 (1901) * Success (1902) * Hernando de Soto; together with an account of one of his captains, Gonçalo Silvestre (1903) * Progress (1905) * His People (1906) * Santa Teresa: being some account of her life and times (1907) * Rhymes from a world unknown (Preface) (1908) * Faith (1909) * Hope (1910) * Charity (1912) * A Hatchment (1913) * Scottish Stories (1914) * Bernal Diaz del Castillo: being some account of him (1915) * Brought Forward (1917) * A Brazilian mystic: being the life and miracles ofAntonio Conselheiro

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

(1920)

* Cartagena and the Banks of the Sinú (1920)

* The Conquest of New Granada: Being the Life of Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada (1922)

* The Dream of the Magi (1923)

* Doughty Deeds: an account of the life of Robert Graham of Gartmore (1925)

* Pedro de Valdivia, conqueror of Chile (1926)

* Redeemed: And Other Sketches (1927)

* Jose Antonio Paez (1929)

* Thirty Tales & Sketches (1929)

* Writ in sand (1932)

* Portrait of a dictator: Francisco Solano Lopez (1933)

* Mirages (1936)

* Rodeo: A Collection of the Tales and Sketches (1936)

* Reincarnation: The Best Short Stories of R. B. Cunninghame Graham (1979) posthumous

Further reading

* Hubbard, Tom (1982), "Revaluation: R.B. Cunninghame Grahame", in Murray, Glen (ed.), ''Cencrastus

''Cencrastus'' was a magazine devoted to Scottish and international literature, arts and affairs, founded after the Referendum of 1979 by students, mainly of Scottish literature at Edinburgh University, and with support from Cairns Craig, then a ...

'' No. 8, Spring 1982, pp. 27 - 30,

* Munro, Lachlan (ed.) (2017), ''An Eagle in a Henhouse: Selected Political Speeches and Writings of R.B. Cunninghame Graham'', Ayton Publishing Ltd., Turriff

Turriff () is a town and civil parish in Aberdeenshire in Scotland. It lies on the River Deveron, about above sea level, and has a population of 5,708. In everyday speech it is often referred to by its Scots name ''Turra'', which is derived fr ...

,

* Munro, Lachlan (2022), ''R.B. Cunninhame Graham and Scotland: Party, Prose and Political Aesthetic'', Edinburgh University Press

Edinburgh University Press is a scholarly publisher of academic books and journals, based in Edinburgh, Scotland.

History

Edinburgh University Press was founded in the 1940s and became a wholly owned subsidiary of the University of Edinburgh ...

,

* Sassi, Carla & Stroh, Silke (2017), ''Empires and Revolutions: Cunninghame Graham and his Contemporaries'', Scottish Literature International, Glasgow

* Taylor, Anne (2005), ''The People's Laird'', The Tobias Press

* Watts, Cedric & Davies, Laurence (1979), ''Cunninghame Graham: A Critical Biography'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Footnotes

Bibliographies

*''A bibliography of the first editions of the works of Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham'', compiled with a foreword by Leslie Chaundy, London: Dulau, & Co. 1924 *''Cunninghame Graham and Scotland: an annotated bibliography'', John Walker, Dollar: Douglas S. Mack, 1980References

*''The Adventures of Don Roberto'' A Caledonia TV production for BBC Scotland, broadcast on BBC2 2008-12-15. *''The People's Laird: A Life of Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham'' by Anne Taylor, The Tobias Press, 2005 *''Gaucho Laird: The Life of R.B. Don Roberto Cunninghame Graham'', by Jean Cunninghame Graham, Long Riders' Guild, 2004 *''R.B. Cunninghame Graham: Fighter for Justice'', by Ian M. Fraser (privately published 2002) *''Revaluation: R.B. Cunninghame Graham'', byTom Hubbard

Tom Hubbard (born 1950) was the first librarian of the Scottish Poetry Library and is the author, editor or co-editor of over thirty academic and literary works.

Biography

Tom Hubbard was born in Kirkcaldy.

After obtaining first class honour ...

, in ''Cencrastus

''Cencrastus'' was a magazine devoted to Scottish and international literature, arts and affairs, founded after the Referendum of 1979 by students, mainly of Scottish literature at Edinburgh University, and with support from Cairns Craig, then a ...

'' No. 8, Spring 1982, pp. 27 – 30,

*''R.B. Cunninghame Graham'', by Cedric Watts, Boston, Mass.: G. K. Hall, Twayne, 1983.

*''Cunninghame Graham: A Centenary Study'', Hugh MacDiarmid

Christopher Murray Grieve (11 August 1892 – 9 September 1978), best known by his pen name Hugh MacDiarmid (), was a Scottish poet, journalist, essayist and political figure. He is considered one of the principal forces behind the Scottish Rena ...

, with a foreword by R.E. Muirhead, Glasgow: Caledonian Press, 1952

*''Cunninghame Graham: A Critical Biography'', Cedric Watts and Laurence Davies, Cambridge ng.

Ng, ng, or NG may refer to:

* Ng (name) (黄 伍 吳), a surname of Chinese origin

Arts and entertainment

* N-Gage (disambiguation), a handheld gaming system

* Naked Giants, Seattle rock band

* '' Spirit Hunter: NG'', a video game

Businesses ...

New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979

*''Don Roberto: being the account of the life and works of R. B. Cunninghame Graham, 1852–1936'', A. F. Tschiffely, London, Toronto: William Heinemann, 1937

*''A Modern Conquistador: Cunninghame Graham His Life and Works'', by Herbert Faulkner West, Cranley Day, 1932

*''Don Roberto: vida y obra de R. B. Cunninghame Graham, 1852–1936'', A. F. Tschiffely; versión castellana de Julio E. Payró, Buenos Aires: Guillermo Kraft, 1946

*''El Escocés Errante: R. B. Cunninghame Graham'', Alicia Jurado, Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, c1978

*''Robert and Gabriela Cunninghame Graham'', Alexander Maitland, Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons Ltd, 1983

*''The Friendship between W.H. Hudson and Cunninghame Graham; translation of an article ... in the Buenos Aires illustrated weekly Acquí Está'', José Luis Lanuza, Argentina: Florencio Varela, n.d.

*''Lecture on R.B. Cunninghame Graham for the Anglo-Argentine Society, 24 January 1979'', Jean Polwarth, London: n.p., 1979

*''Jorge Luis Borges Lecture on R. B. Cunninghame Graham for the Anglo Argentinian Society, 30 September 1986'', Alicia Jurado, Royal Society of Arts, London: n.p., 1986

*''Personalidad de Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham: extracto de la tesis doctoral ... en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Madrid sobre: Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham : personalidad del autor y estudio crítico de sus ensayos'', Julio Llorens Ebrat., Madrid: Florencio Varela, 1963

*''Testimonio a Roberto B. Cunninghame Graham'', Buenos Aires: P.E.N. Club Argentino, 1941

*''The North American Sketches of R. B. Cunninghame Graham'', John Walker (ed.), Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1987

*''The Scottish Sketches of R.B. Cunninghame Graham'', John Walker (ed.), Edinburgh, Scottish Academic Press, 1982

*''The South American Sketches of R. B. Cunninghame Graham'', John Walker (ed.), Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1985

*''An Eagle In a Hen-House: Selected Political Speeches and Writings of R. B. Cunninghame Graham'', Lachlan Munro, The Deveron Press, 2017.

*''Joseph Conrad's Letters to R. B. Cunninghame Graham'', Cedric Watts (ed.), London, Cambridge University Press, 1969

*''South London Chronicle, 9 June 1888, page 7, SHRA Conference (Tuesday).

*''Empires & Revolutions: Cunninghame Graham & His Contemporaries.' ''Carla Sassi and Silke Stroh'' ''(Eds.) 2017, ASLS.''

External links

Archival collections

Guide to the Anne Elizabeth Bontine Diaries and Other Materials.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Other

Biographical Profile

at ''ElectricScotland.com''

* *

R. B. Cunninghame Graham, Rauner Special Collection, Dartmouth College Library, N.H.

* ttp://www.horsetravelbooks.com/rbcg.htm The Cunninghame Graham Collection* *

First Foot – Cunninghame-Graham

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cunninghame Graham, Robert 1852 births 1936 deaths Anglo-Scots Writers from London People educated at Harrow School Presidents of the Scottish National Party Scottish journalists Scottish explorers Scottish nationalists Scottish travel writers 20th-century Scottish historians Scottish biographers Scottish essayists Scottish socialists Scottish Liberal Party MPs Scottish translators Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Scottish constituencies UK MPs 1886–1892 Deaths from pneumonia in Argentina Scottish Labour Party (1888) politicians British political party founders 19th-century Scottish historians